Introduction: The One-Room School

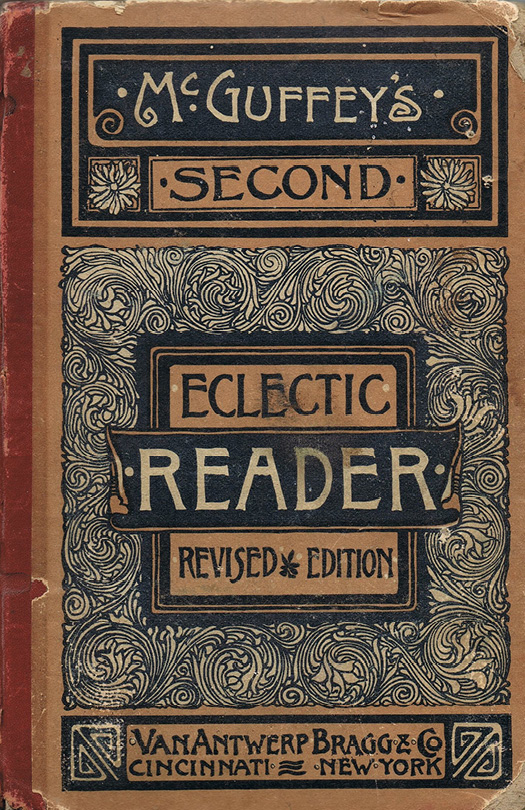

It is hard for students of the twenty-first century—even those who attend the few remaining one-room schools still found across the country—to imagine what schools might have been like one hundred plus years ago. Schools were furnished minimally, even sparsely, with simple wooden desks or benches where students sat with individual chalkboards (called “slates”), where the single teacher arrived early to build a fire in the wood stove or to set an urn of water with a single ladle near the door for drinking; new books were rarely seen; and students had to share books, paper and supplies, and often came to school barefoot or without proper clothing.

Students without shoes at a rural mountain school, circa 1930

Courtesy Gail L. Jenner Collection

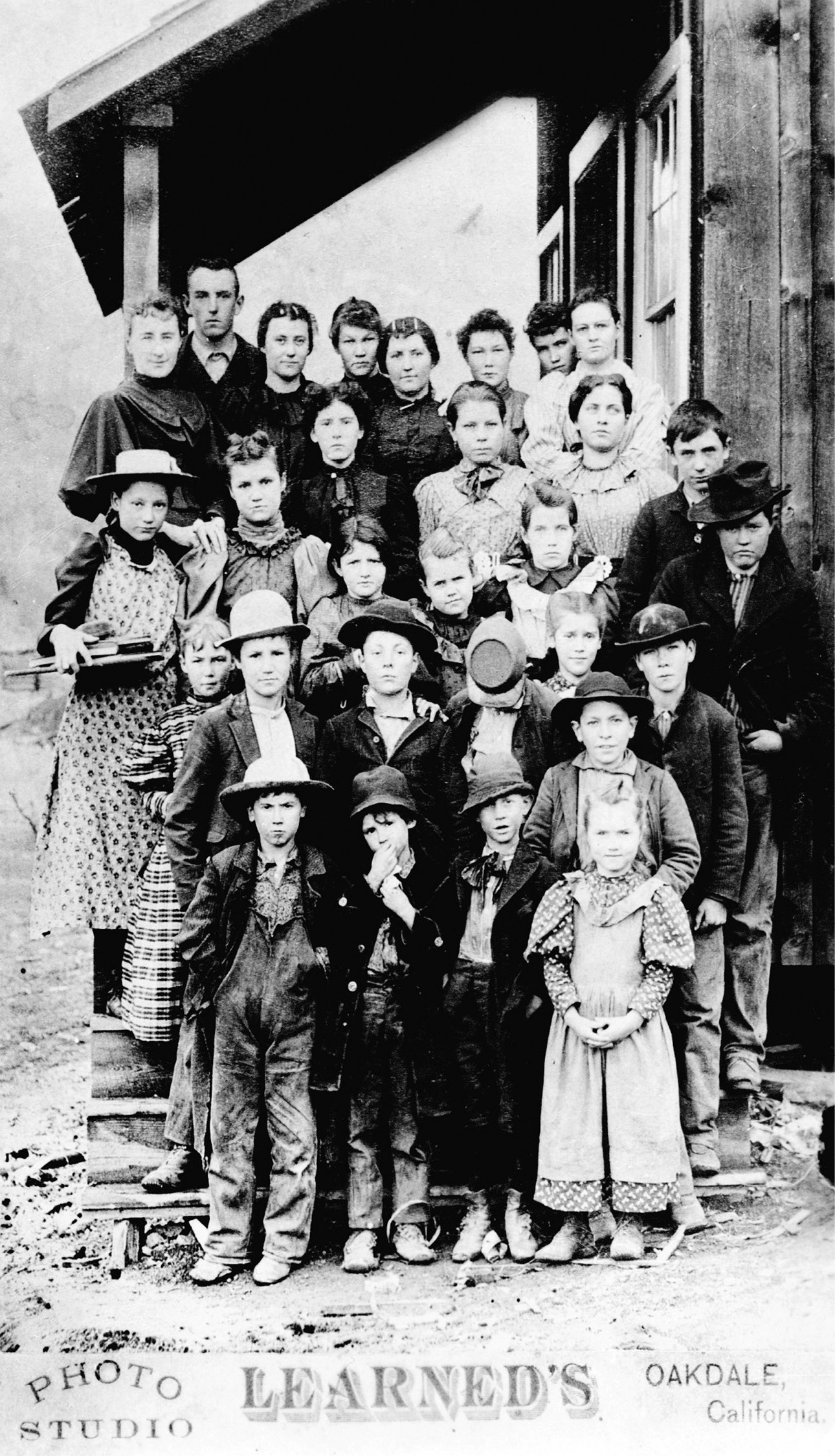

Indeed, there was a time in American history when almost every child who was not taught at home was educated in a small, often isolated, one-room school. These schools were initially governed by local entities, thus each school, including its furnishings, school materials and curriculum, even the quality of teaching, varied from one locale to another. Quite often, teachers had to rotate between schools because there were too few qualified teachers. Where winters were severe or pupils were needed at home, attendance was sporadic. Moreover, some districts required female teachers, if they were single, to leave their post if they married during the year. Many communities felt “schoolmarms” should remain single in order to teach effectively, and many young teachers were hardly older than their students.

Students gather at the Hooperville School in northern California, circa 1870s and 1880s

Courtesy Fort Jones Museum

President John Adams began his career as a teacher in a one-room school in Boston, and Abraham Lincoln was educated in a one-room schoolhouse—as were many of our other presidents and Founding Fathers. Many other influential Americans got their starts in one-room schools. Henry Ford loved his one-room school so much he eventually had it moved to a museum; award-winning author Joyce Carol Oates attended one in New York; Tony Hillerman, successful and noted author, attended Georgetown School in rural Oklahoma; and Laura Ingalls Wilder, whose family moved so often that she was not always able to attend school, began teaching in a one-room school at age fifteen. Her memories became the foundation for her stories and novels, and children of the 1970s and 1980s learned of a “typical” one-room schoolhouse through the television series Little House on the Prairie, which was based on Wilder’s life and writings.

At the start of the twentieth century, at least half of American children were enrolled in the more than 210,000 one-room schools found across the nation. Whether they were made of stone or logs, sod or planks, these facilities became the heart of most communities, especially in the West where neighbors were separated by miles of prairie or tucked into isolated valleys. After World War I, however, many of these schools began to close. Migration away from the country and into cities minimized the need for so many schools; the trend toward consolidation had begun.

Today there are still as many as 400 operational one-room schools in the United States, mostly in rural areas. And more than 75 percent of them are in the states of Nebraska, Montana, South Dakota, California, and Wyoming.