It rained all morning. Raindrops streamed down the window as Stella practised the pianoforte. Aunt Condolence sat beside her and rapped her smartly on the knuckles every time she played a wrong note, which was often. The piece she was learning, ‘Waltz for the Pretty Flowers’, seemed even harder than usual, and by the end of it, Aunt Condolence was furious and Stella was in tears.

After luncheon (Mock Turtle Soup, Collared Eels, Pickled Tongue and Vegetable Marrows, Cabinet Pudding and Custard), the rain stopped and the Aunts were able to take their promenade along the Front. Pale sunshine glinted on the little white-capped waves, but the breeze was cold and damp, and dark clouds loomed in the distance. Aunt Deliverance’s beady black eyes peered out from a cocoon of shawls and blankets. Ada pushed the Bath chair. Aunt Temperance and Aunt Condolence walked beside it and Stella followed behind.

The Aunts always walked down the hill from the Hotel Majestic and then along the Front, past all the smaller hotels, the pleasure gardens and the pier, all the way to the lighthouse. Then they turned and walked back.

Stella liked looking at the sea. It was sometimes grey, sometimes greyish-blue or green, and often there were sailing ships or steamers. The Front was generally busy. There were many convalescents huddled in invalid chairs, old ladies with tiny dogs and nursemaids pushing perambulators full of muffled-up babies.

Occasionally, a young gentleman hurtled along on a high-wheeled bicycle, and the Aunts and all the other old ladies twittered disapprovingly. Sometimes a file of neatly dressed girls from Miss Mallard’s Academy for Young Ladies walked past with a grim-looking governess, and that was always interesting. Stella had often thought it would be agreeable to do her lessons with other girls. But, from the look of them, the girls from Miss Mallard’s Academy had a miserable time. They walked two by two, their gloved hands folded primly and their eyes down, and they never whispered to each other or smiled.

Her favourite part of the promenade was the pier. It stretched out over the sea, the little waves frothing around its elegant, spindly legs. It had curly lampposts, which seagulls liked to perch on, and stalls selling cockles and pies and vividly coloured sweets. Cheerful, tinny music came from a barrel organ and the steam-powered merry-go-round. At the end of the pier was a theatre. It had white domes and fluttering flags. It looked like a palace.

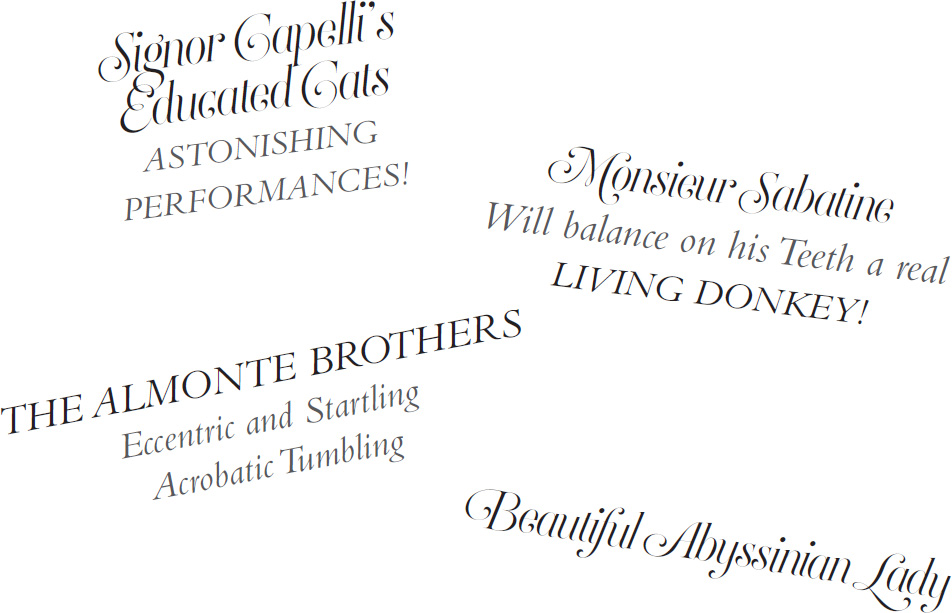

Stella longed to walk out along the pier. But it cost a penny, which she did not have, and Aunt Deliverance said it was Quite Vulgar, so she could only gaze from the Front as they walked past every day. At the entrance to the pier was a gate with turnstiles. The walls on either side were covered with posters and playbills, pasted over each other.

Aunt Deliverance said, ‘Don’t dawdle, child,’ as they walked briskly along the Front, past the private villas and boarding houses and fishing boats, all the way to the shipwreck memorial (Erected to commemorate the Calamitous Wreck of the Charlotte, 1752, 140 souls lost) below the lighthouse. The shipwreck memorial marked the edge of Withering-by-Sea. Beyond it lay the marsh, which stretched as far as the horizon.

Ada heaved the Bath chair around and they started back.

As they drew level with the pier again, an autocratic voice called, ‘Good afternoon,’ and an elderly lady heaved into sight. It was Miss Ollerenshaw, an acquaintance of Aunt Deliverance, a resident of the Hotel Imperial. Miss Ollerenshaw wore a ruffled black dress, a hat decorated with a huge swaying bunch of curly black feathers, a black fur tippet and several strings of jet beads. Her maid walked behind her, clutching the leads of three yapping Scottish terriers and carrying a pile of rugs and shawls and an enormous black umbrella.

Stella made a bob and said, ‘How do you do, Miss Ollerenshaw,’ and after a minute or two (as the Aunts and Miss Ollerenshaw talked about the weather, and then about how they had to watch the maids to ensure they did their work properly, and then about the scandalous events at the Hotel Majestic), she drifted away and gazed at the posters.

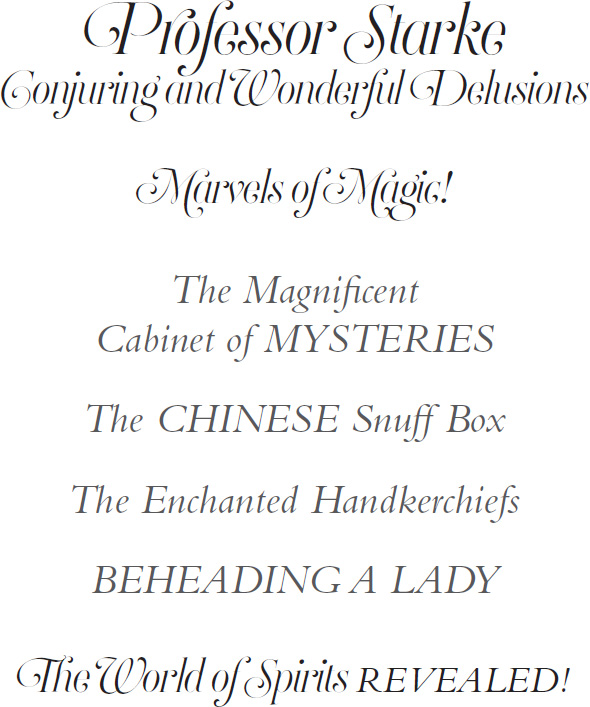

There was a picture of the tiger. It had staring eyes and impressive teeth and claws. Stella was admiring it when another poster caught her attention. With a jolt, she recognised the thin face staring out of the picture. It was the Professor. He was dressed in black. He was standing beside a pillar, which held a rabbit and a bowl of goldfish, and on his other side was a draped curtain. He had one hand raised and seemed to have lightning shooting out of it. Stella read:

Stella stared blankly at the poster. The Professor was a magician. It made him seem even more frightening and mysterious.

She thought of Mr Filbert’s silver bottle, hidden safely under her mattress at the hotel. What could it be that was so important to him? Perhaps he would do magic to try to discover where it was. Perhaps he was doing magic right now.

As she pondered this disconcerting thought, she heard a whimper. It sounded like a seagull or a cat. She looked around. There was nothing close by. She heard the sound again. It was a kind of sob and it seemed to come from under her feet. She walked to the railing, leaned over and looked down at the beach.

A small figure crouched in the shadow under the pier. His arms were wrapped around his knees and his head was down.

Stella looked over her shoulder. The Aunts were still deep in conversation with Miss Ollerenshaw. Aunt Condolence was pointing towards her stomach and making a twisting gesture with her fingers. They had started on the topic of their health, which would certainly keep them occupied for some time.

Stella hung over the railing and called, ‘Are you all right?’

He looked up. She recognised him. He was the thin, pale boy who had been with the Professor at the hotel. His face seemed very white against the dark shadow under the pier, and there were black smudges beneath his eyes. He shrugged miserably and looked down again.

Stella asked, ‘How did you get down there?’

He didn’t answer, but she spied a rusty ladder bolted to the sea wall. She looked back at the Aunts and Miss Ollerenshaw. Aunt Condolence was making a vigorous gesture with her hands as if she were wringing out a dishcloth, and the others were nodding. They were clearly still discussing Aunt Condolence’s insides.

Stella pulled off her gloves. ‘I’m coming down,’ she said, and climbed over the railing.