Imperial Germany’s role as a colonial power on the international stage was short-lived. German South West Africa came to an end when the government surrendered to the South Africans at Khorab in 1915. The territory was placed under military rule for the duration of World War I. Louis Botha, the South African premier and commander-in-chief of the Union troops, could make no answer to the capitulating Imperial governor, Dr Theodor Seitz, when the latter said that South West Africa’s fate would not be determined there, but by the course of the war in Europe. History vindicated Seitz’s prophecy. Under the Treaty of Versailles, signed on 26 June 1919, Germany had to renounce all its colonial holdings abroad.

The road to independence was long and hard.

Corbis

“The German colonies in the Pacific and Africa are inhabited by barbarians,” wrote South Africa’s prime minister Jan Christiaan Smuts in 1918. “They are incapable of ruling themselves, and it would furthermore be impractical to attempt to implement the idea of self-government in the European sense.” Smuts’s suggestion was that South West Africa should be incorporated into South Africa – although in the end the victorious Allies agreed to restrict themselves to an administrative and supervisory role as far as Germany’s former colonies were concerned.

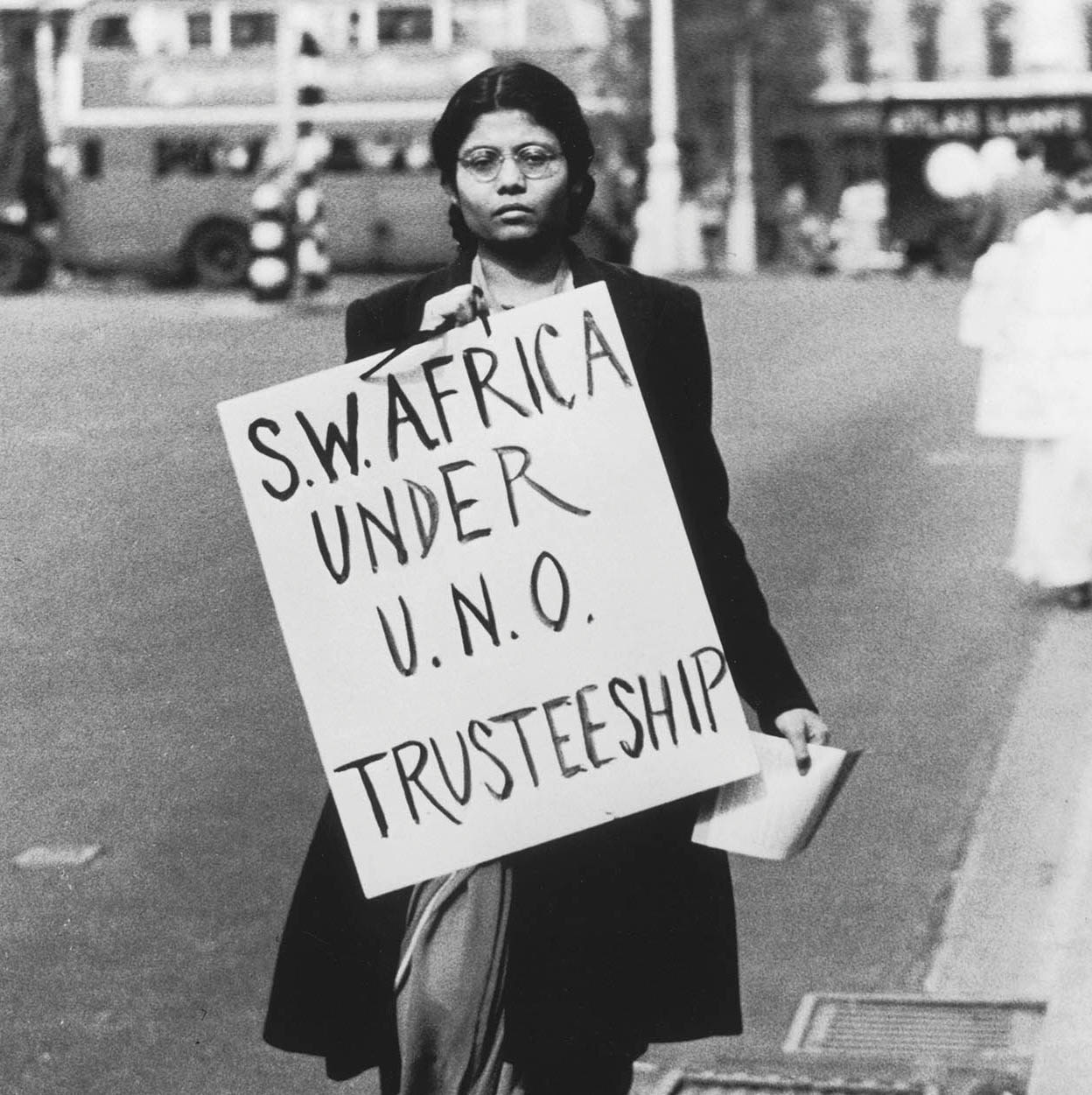

A demonstrator picketing outside South Africa House in London to demand that South West Africa be put under United National Trusteeship, 1948.

Getty Images

As a result, South Africa was awarded responsibility for the country, but only as a League of Nations “trust territory”. Nevertheless, this meant that, for the following 75 years, Pretoria’s influence would extend all the way north as far as the southern border of Angola.

A new administration

In a show of strength by South Africa, a number of German “undesirables” (officials, defence force personnel and police) were turfed out of South West Africa immediately after the Armistice on 11 November 1918. Some 1,400 nationals returned to Germany voluntarily, while 6,374 were deported – nearly half of the territory’s German population. The German diamond concession was given to Consolidated Diamond Mines, which later became the world-famous De Beers.

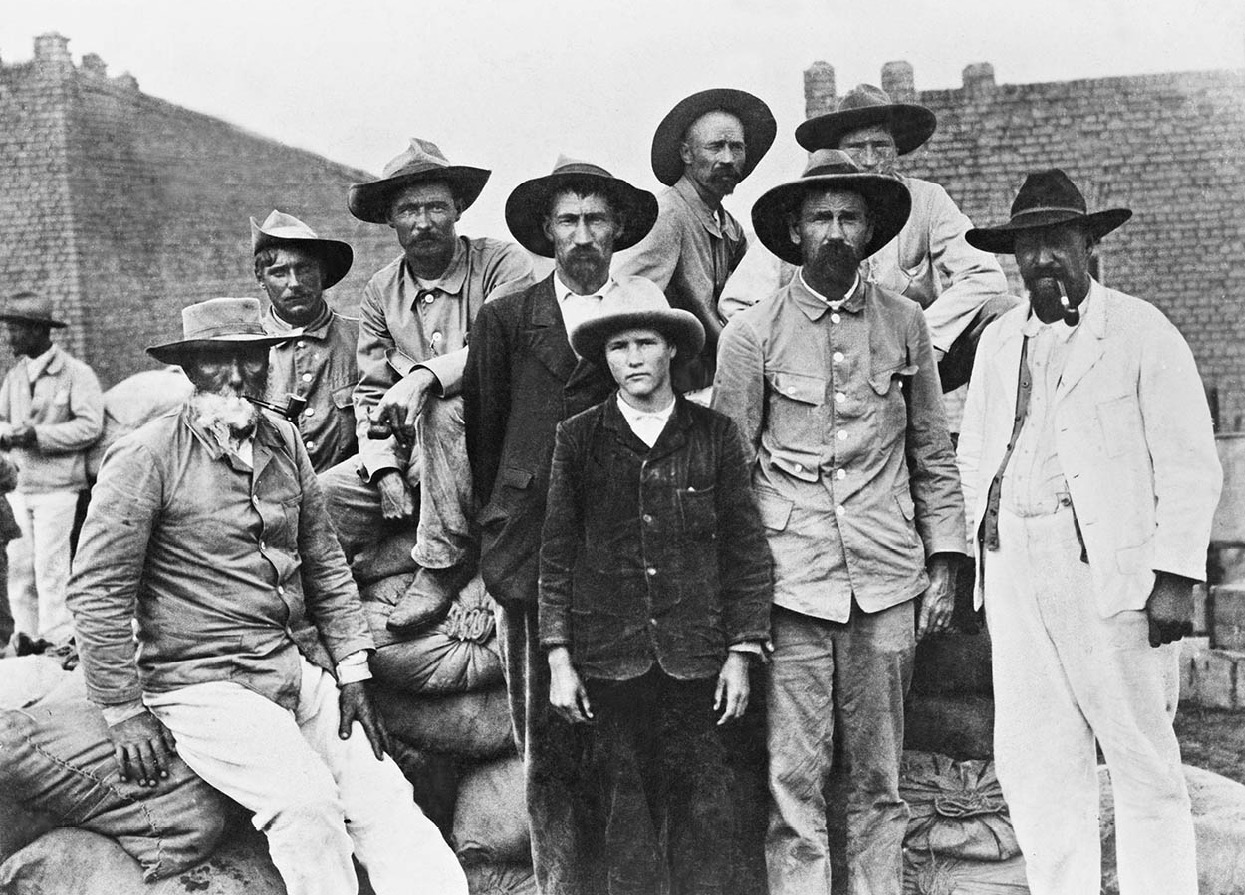

A group of Boers working for a German transport service.

Mary Evans Picture Library

The agreement formulated by the Allies, according to which South West Africa was made an “integral part” of South Africa, was formally ratified by the League of Nations on 17 December 1920. The ambiguities implied by this phrase “integral part” were to prove a major stumbling block in the administration of the territory over the next few decades; a vital definition was left too open to interpretation. South Africa’s responsibilities were outlined in this sentence: “The mandatory shall promote to the utmost the material and moral well-being and the social progress of the inhabitants of the territory subject to the present mandate.” In the years that followed, the formulation became more specific: the territory should, under the protection of South Africa, be guided towards independence.

Beyond merely administering the country, the South African government concerned itself with continuing the white-settlement policy which had been initiated by the previous German administration. In a clear bid to increase the Boer population, it gradually parcelled out more and more of the land to “poor white” settler families from South Africa, rather than to Germans. Between 1915 and 1920, 6 million hectares (15 million acres) of land were given to South Africans. In the years 1928–9, another large chunk of the territory was distributed during the repopulation of Boers who had been living in Angola, while the third, and last, phase of white settlement occurred between 1950 and 1954.

Splits in the Boer Camp

When South Africa was urged by Britain to challenge Germany over South West Africa during World War I it needed little encouragement. One of the main motivations behind the invasion was that a successful military campaign would lead to a reconciliation with the hostile Boers who had settled in the colony following the bitter Boer War of 1899–1902. This conflict had split the Boers into two camps: anti-British opponents of the war, and its pro-British supporters (such as the prime minister, Jan Smuts). The rifts ran deep, however, and South Africa did not achieve all that it had been hoping for in terms of reconciliation.

A last stand

The indigenous population’s hopes that colonial land division and allotment would be revised after the defeat of the Germans were, therefore, soundly dashed. Nonetheless, various groups were determined to fight for their land. Chief Mandume, for example, took a stand against British-South African territorial demands in Ovamboland.

The frustrated hopes concerning the transfer of power in Windhoek, combined with South Africa’s interference in the line of succession of chiefs among one of the most powerful Nama groupings, the Bondelswarts, gave rise to a major Nama uprising against the South African administration in 1922.

Unfortunately, whether resistance came from Chief Jacobus Christiaan, who lost 64 warriors, or the Rehoboth Basters, who had hoped for more autonomy after the South African takeover, the Nama had no chance against an enemy that was militarily far superior. Even the battle-hardened Bondels, for example, who had long held their own in guerrilla fighting against the German colonial forces prior to World War I, now found themselves fighting an adversary which, having been through similar experiences in the Boer War, was well-versed in those very same tactics. The South African government responded by sending in wave upon wave of fresh troops. Retribution for the unrest was heavy; the Basters lost even the right to appoint their own “kaptein”, or leader. Instead, they now had to submit to the authority of a white magistrate, a situation which continued until 1976.

Divide and Rule

Continuing the policies of the German administration that preceded it, the South African mandatory government consistently interfered in the succession and appointment of local chiefs – with varying degrees of success. Its main tactic was to bring the black population under control by installing lackey chiefs, ready to do its bidding. In this way South Africa’s area of influence was gradually extended into Ovamboland and the northern territories lying beyond the so-called Red Line – an area which the Germans had tended to avoid. The extreme northern and Kalahari border regions to the east were, however, largely unaffected.

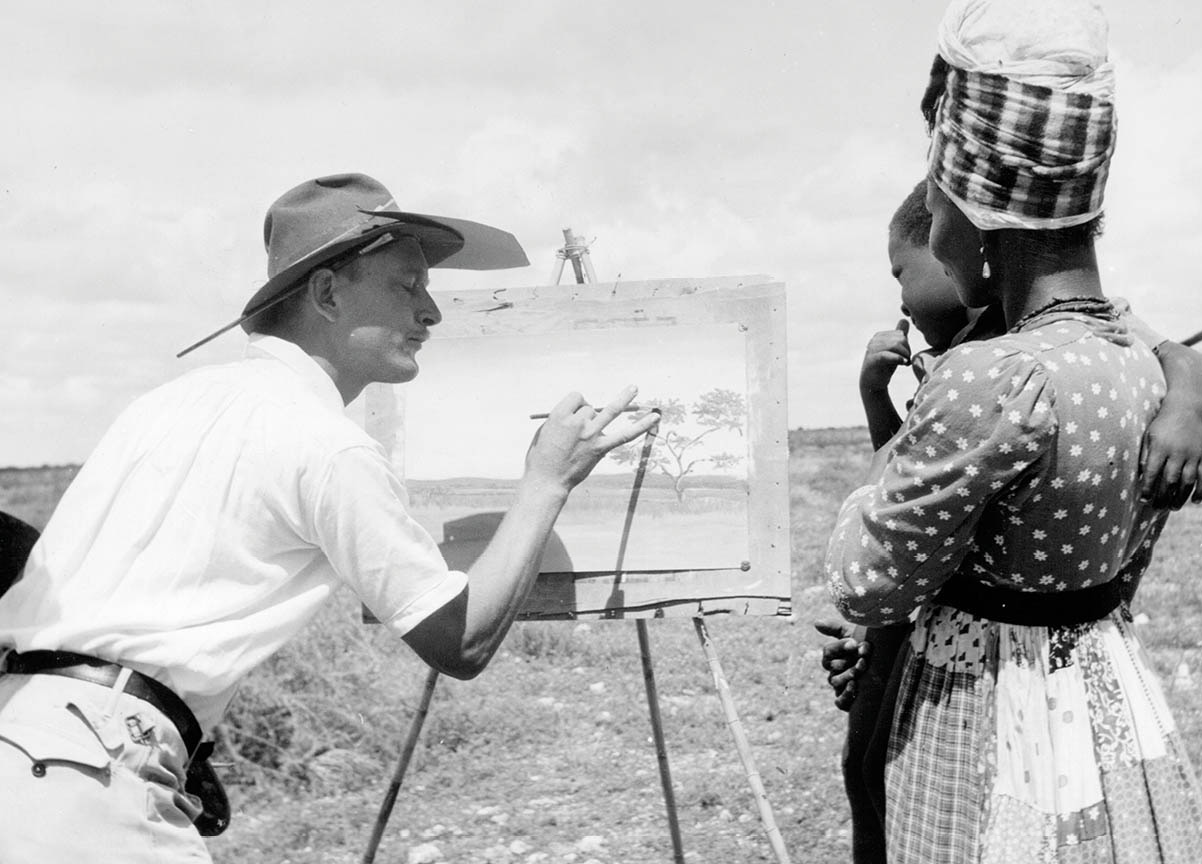

A karakul farmer shows off his painting skills, 1939.

Mary Evans Picture Library

Yet despite their efforts to grab control of as much land in the territory as possible, the South Africans invested very little in Namibia’s infrastructure. An exception was the construction of several railway lines – from Swakopmund to Walvis Bay, from Otjiwango to Outjo and from Karasburg to Upington in South Africa, as well as from Windhoek to Gobabis. The continent’s very first automatic telephone exchange was installed in Windhoek in 1929.

The isolated, time-warped flavour of Namibia at this time is well expressed by the missionary Dr Heinrich Vedder in the foreword to his book Old South West Africa (1934): “This book should only be read by people who love South West Africa; for it contains many things which are of lesser importance in comparison to the major world events of this period, things which could only be of value to someone who has already become attuned to our sunny country.”

But in the end, it was these “major world events” that were to determine Namibia’s fate – affecting as they did the political consciousness of the white settlers. Essentially, the settlers were divided into two camps, differentiated by language: Afrikaans-speakers loyal to the South African Union advocated a complete union with South Africa; the majority of German-speakers were, by contrast, largely faithful to the Geneva Mandate. It was their hope that, once Germany had recovered its former strength, it would bring a swift end to South Africa’s administration of Namibia and usher in a new age of independence for the territory.

The war years

In the 1930s, National Socialist propaganda and agitation served to exacerbate these divisions. The South African government empowered the territorial administration to forbid foreigners (such as German immigrants) the right to join political organisations – but there was a large loophole: many German-speakers had become naturalised citizens, or carried two passports. The Deutscher Bund (German Union) and Die Verenigde Nasional Suidwes Party (United National South West Party, VNSWP) were the major political forces of the time, one in favour of the mandate, the other for annexation to South Africa.

The outbreak of World War II put an end to these disputes. In most cases, speaking fluent German was sufficient grounds for the South African officials to detain men of army age in internment camps, regardless of whether they were naturalised British-South African subjects, had dual German-South African citizenship, or were recent immigrants.

During the war years, the women tended the farms. As had been the case in World War I, German property and possessions were placed under the jurisdiction of a “Custodian for Enemy Property”. The fate of Germans and their families interned in the South African prison camps of Andalusia and Baviaanspoort remained uncertain until long after the outbreak of peace.

Driving along the beach to reach the diamond mine.

Getty Images

Dr Malan and his National Party’s (NP) narrow victory in South Africa in May 1948 put a final stop to all actions directed against South West Germans, even to the threat of deportation, and the last detainees were allowed to go back home to their farms. Until the mid-1970s, South West Germans thanked the NP by adhering to it with unswerving loyalty, although Pretoria’s racial policies did not always meet with their approval.

Defying the United Nations

In 1947, South Africa formally announced to the United Nations its intention to incorporate Namibia as a fifth province, arguing that local chiefs had supported the annexation in a communal vote. However, they played down the dissenting voices of many Herero and Nama chiefs, as well as those of the African National Congress (ANC) and South Africa’s Communist Party, both of which had always demanded that the UN provide for an honest administration for South West Africa, as specified by the UN General Assembly.

The UN rejected the plan, however, and from that moment on, South Africa’s guardianship of the territory was increasingly called into question. Over the next 21 years, the General Assembly and Security Council convened the International Court of Justice in The Hague at least six times in reference to South West Africa. However, a binding, clear statement of the territory’s international status, as well as a definition of the limits of South Africa’s responsibility, remained lacking.

South Africa chose to ignore the UN’s legal pressure; from 1948, for example, the country simply ceased to file the annual reports it was supposed to present on its “trust territory”.

The great wave of African independence at the end of the 1950s and beginning of the 1960s swept over the continent without touching Namibia, although it left clear traces behind in the minds of the country’s black population. Yet where black Namibians managed to organise themselves to protest against their lack of political and civil rights, they were met with heavy-handed repression, as in the events of December 1959 when 13 black demonstrators in Windhoek were felled by club-wielding police. The victims had been protesting against their forced resettlement to the new blacks-only township of Katutura.

A Sad Record

There can be no other country in the world – especially one with such a small population – that matches Namibia’s sad record as far as clarifying its international status is concerned. In its decades of transformation from colonial protectorate to mandate to bone of international contention to – finally – universally acknowledged independent state, Namibia has amassed a collection of verdicts, papers, requests and related literature that is unequalled. Despite this, it was not until 1968 that the South Africans’ presence was ruled illegal and The Hague demanded that South Africa terminate its South West African administration.

According to South Africa’s policy of apartheid, the black population within the territory of the mandate was nominally permitted to regulate its own affairs. However, all the crucial issues – such as international relations – were left up to the government in Pretoria and the Cape Town Parliament.

In the invalid general election of 1978, the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance took 41 seats and the Nationalist Party six. Three smaller parties received one seat each.

An uphill struggle

Between 1949 and 1977, the white population of the mandated area was represented by six delegates in Parliament and four members in the South African Senate. During all this time, only a handful of black Namibian nationalists – such as Mburumba Kerina and Fanuel Kozonguizi – managed to get their voices heard by the United Nations Committee on South West Africa.

However, this era did see the founding of the Ovamboland People’s Organisation (OPO), which led to the founding of the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) in 1960. Although SWAPO initially concerned itself only with labour-related issues, it was increasingly identified as an independence and liberation movement – all the more so after 1966, when the organisation took a decision to fight for freedom with arms.

The diamond industry is still a mainstay of Namibia’s economy.

Getty Images

Bolstered by their administration’s complete disregard for the UN’s resolutions, whites, on the other hand, must have felt sure that nothing was likely to change.

Political developments were one thing, the establishment of an infrastructure in Namibia entirely another. In the 1960s, for the first time since German rule, the country underwent a period of rapid development: roads, water and energy resources, telecommunications, agriculture, tourism and other areas reached a level which placed Namibia a cut above the average African state in terms of living conditions. In the heavily-populated rural north, however, this process only affected marginal areas and was by and large limited to police zones.

The fifth province

Pretoria’s determination to annex Namibia came to a head when, in 1968 and 1969, two constitutional ordinances formally declared the territory to be the fifth province of South Africa. Over the next few years, thousands of young Namibians left the country, either to struggle for independence from abroad or to attend an educational facility not under South African control.

Faced with increasing international pressure, South Africa did make a few fainthearted gestures towards granting civil rights to the black population. In 1973, Prime Minister Vorster created a “native council” for South West Africa – just as SWAPO attained observer status at the UN. In September 1975, a constitutional conference was summoned; since it met in the old German Turnhalle (gymnasium) in Windhoek, this assembly was to go into the annals as the Turnhalle Conference. Its task was to create a constitution for an independent Namibia, and delegates were strictly divided into 11 groups; political parties were still excluded.

Delegates at the historic Turnhalle Conference, whose aim was to create a constitution for an independent Namibia.

Getty Images

Father of the Nation

The dominant figure in modern Namibian politics, Samuel Nujoma was born in Ongandjera in 1929. By 1957 he was dedicated to the liberation cause. Two years later, as leader of the Ovamboland People’s Organisation (OPO), he tabled a first petition to the UN asking that his country be released from South African rule. In 1960, Nujoma helped found SWAPO, and was elected as its first president. Following years of fruitless petitioning, he authorised a policy of armed resistance in 1966, initiating a war of independence that lasted 24 years. Following independence, Nujoma was inaugurated as President of Namibia on 21 March 1990, a post to which he was re-elected in 1994 and 1999.

Resolution for change

Some 18 months later, in March 1977, a first draft of the constitution was presented; much influenced by South Africa, it presented a model for an ethnically segregated country. Meanwhile, the five Western members of the Security Council – the United States, West Germany, Great Britain, France, and Canada – closed ranks. This group urged South Africa to guarantee that the Turnhalle Conference would be nullified, and that general and free elections would be held in order to exercise every Namibian’s right to self-government – something which had already been demanded by the United Nations in countless resolutions.

Though the Turnhalle Conference did not produce any tangible results, it did succeed in loosening the knots of apartheid. For the first time, black, white and coloured people sat round the table, striving to reach a consensus in lengthy negotiations.

South Africa only partially yielded to the suggestions of the five Western powers. In 1977, General Administrator Marthinus Steyn was appointed to govern the territory until its independence, serving as a counterpart to the UN Special Commissioner for Namibia, Martti Ahtisaari. In keeping with the spirit of the Western demands, which were officially formulated in the international arena as UN Resolution 435 a year later, Steyn removed several mainstays of the hated apartheid laws before the year was out. Segregation also began to be lifted in urban residential areas, a process that lasted until 1980.

Defying the dictates of Resolution 435, South Africa initiated general elections in Namibia in 1978 under its own auspices, without the supervision of the UN. For the first time in the country’s history, elections were held on a one- person, one-vote basis. Despite SWAPO’s call to boycott elections, 81 percent of the 421,600 registered voters took part. The five Western powers declared the election to be invalid.

Herero men and women marching in traditional and military attire.

Getty Images

On the advice of South Africa, the representatives formed a national congress. However, this legislative body was limited in its powers and constantly subject to South African intervention – as happened when it attempted to implement a law against racial discrimination, and when it wanted to drop South African holidays.

In January, 1983, the DTA, unable to govern under these conditions, stepped down. In the years that followed, Pretoria laboriously attempted to re-establish some measure of Namibian self-government – for example, the general administrator, a South African official, was effectively left to stand alone as the territory’s sole administrator.

In 1985, what was to become the very last “temporary government of national unity” was formed. It, too, lacked credibility, however, for in constitutional questions South Africa again demanded the consensus of all parties.

San (Bushmen) trackers were recruited by the South African army during the mandate years.

Mary Evans Picture Library

Armed conflict

At the beginning of the 1960s, SWAPO took a joint decision with the Organisation for African Unity: they would resort to arms in the struggle for independence if diplomacy should prove fruitless. The historic first skirmish with the South African police took place not far from Ongulumbashe, in northwest Ovamboland, in August 1966 (today, 26 August is Namibia’s Remembrance Day holiday). This marked the start of years of guerrilla and border warfare which were to end only in April 1989.

After Angola’s independence in 1975, the armed conflict in Namibia became more and more bound up with the geopolitical interests of the superpowers and their representatives in southern Africa. The Soviet Union and Cuba supported Angola’s Marxist MPLA government in Luanda; on the other side, the United States contributed aid to the pro-Western resistance movement UNITA. As long as Namibia’s political parties adhered to one or the other of these alliances, all attempts at Namibian unity were doomed to failure.

After a general strike in 1971 involving Ovambo workers in particular, followed by uprisings in Ovamboland in 1972, martial law was imposed in the north for the first time, and controlled by the South African army. This remained in place right up until shortly before the 1989 elections.

After 1975, Namibia’s volatile northern regions became a deployment area for South African military intervention and action in Angola. SWAPO’s Angolan headquarters also came under repeated fire, most infamously on 4 May 1978, when an air attack destroyed their camp at Cassinga. Several hundred uniformed men, as well as women and children, were killed.

Superpower involvement

Despite the propitiatory announcement of a plan for the solution of the Namibia question, it would be another 11 years before Security Council Resolution 435, which had met with a broad consensus in 1978, was realised. Time and again, the parties accused one another of setting unrealistic conditions which interfered with the plan’s execution. Positions became completely entrenched when the US and South Africa made the enactment of Resolution 435 contingent on Cuba’s withdrawal from Angola (the so-called Cuban linkage).

In the light of the threat from UNITA, the withdrawal of its defending power’s troops was totally unacceptable to the MPLA government in Angola. Nor could the United Nations make progress on the Cuba demand, as Resolution 435 was aimed specifically at a solution in Namibia, rather than addressing the security and balance of powers in neighbouring countries.

Finally, in 1988, under the direct supervision of the USSR and the USA, the three countries of South Africa, Angola and Cuba met a number of times in Cairo, Brazzaville and New York, until Resolution 435 was inextricably linked with the total withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola.

The independence process was aided by the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG), consisting of some 7,000 people from 110 countries.

Agreement at last

Once agreement between the three countries was reached on 22 December 1998, things moved rapidly. Administrators and observers from more than 100 different countries started to pour into Windhoek.

Yet the Namibia question was threatened anew when on 1 April 1989 – the very day set aside for the resolution’s implementation – heavily-armed SWAPO units moved in along a broad front from Namibia’s northern border with Angola. Although Martti Ahtisaari, the authorised UN representative, was prompted to mobilise army units under South African command, conflict was luckily averted. After a quick conference between South Africa, Angola and Cuba, the independence process finally got underway in early May.

Not only did South Africa now lift all its remaining discriminatory laws, but SWAPO fighters were given the option of returning to Namibia as civilians. The withdrawal of all Namibian and South African soldiers still under South African command and their subsequent demobilisation went without a hitch. In June, those SWAPO leaders who had been living in exile abroad were at last able to come home – in triumph.

The repatriation of some 40,000 Namibian exiles and refugees from Angola and Zambia was carried out between May and August, aided by the UN. The next step was to register the Namibians, so that they could take advantage of their unconditional voting rights. More than 700,000 voters were registered, often under exceptionally difficult conditions.

SWAPO’s last rally before its victory at the 1989 elections.

Getty Images

Free elections

In November 1989, Namibia went to the polls to elect a constituent assembly, whose brief it was to create a new constitution for the country. Three parties – the National Patriotic Front of Namibia (NPF), the Federal Convention of Namibia (FCN) and the Namibia National Front (NNF) – each returned a single delegate to the Assembly. Aksie Christelik Nasionaal (ACN) had three delegates; the United Democratic Front (UDF) four. The absolute majority, however, was held by SWAPO, which, with votes from 57 percent of the electorate, was represented by 41 seats in the Assembly; the strongest opposition was the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance, with 28 percent of the electorate and 21 seats. In 22 of the 23 total electoral districts, the two major parties were locked in a head-to-head race. Only in Ovamboland, the most heavily-populated region and SWAPO’s home base, was the party able to use its home advantage and win the day. None of the other nine parties won a single seat here.

The UN confirmed that the election had been free and fair – the proud culmination of 70 years of bitter struggle in Namibia.