For almost a quarter of a century – from the first resolution of the General Assembly ending South Africa’s League of Nations mandate in 1966 to Independence Day on 21 March 1990 – Namibia’s political future made international headline news. A succession of General Assembly and Security Council resolutions, plus decisions of the International Court of Justice, charted the country’s passage through the political reefs.

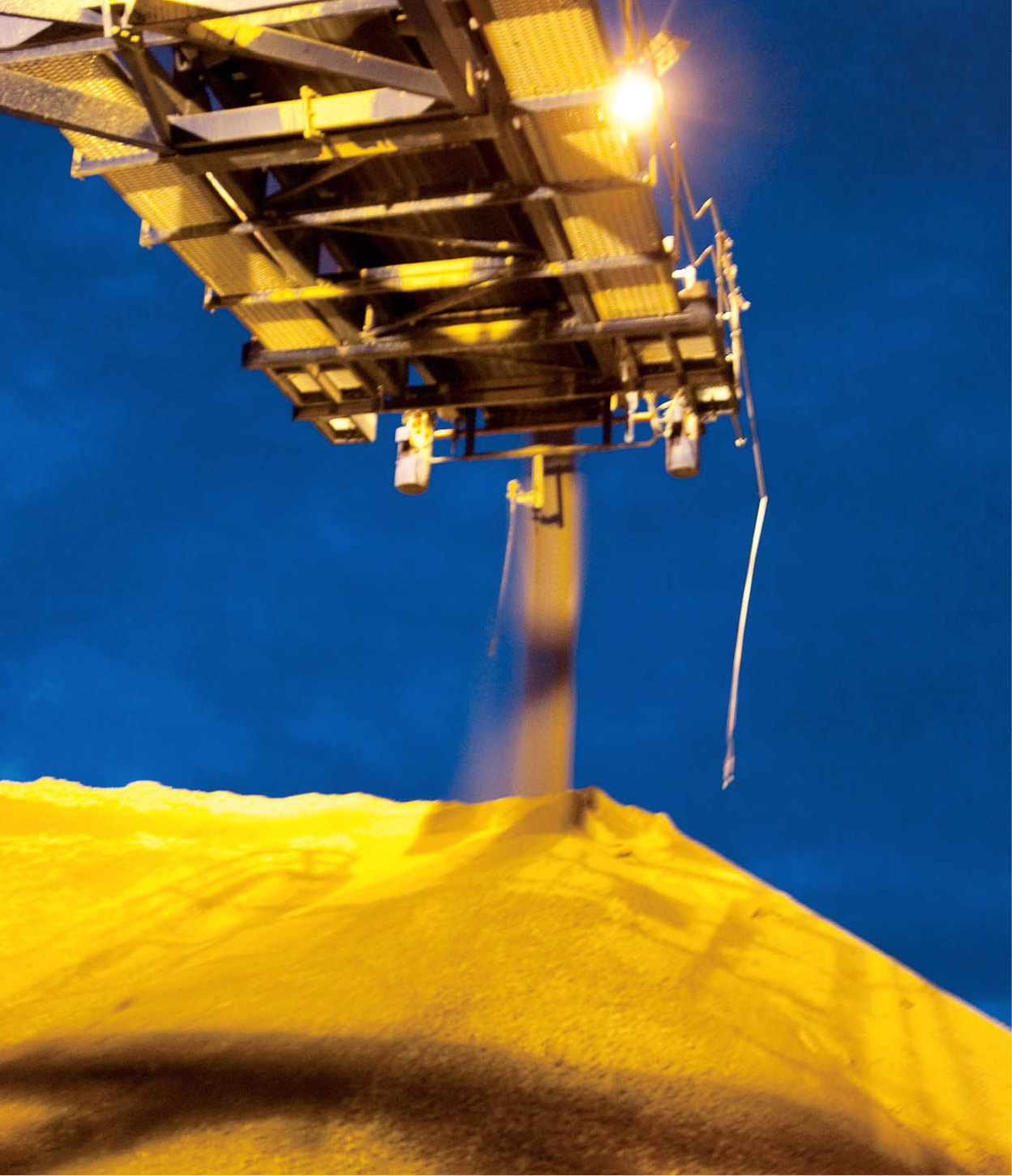

The Trekopjie Uranium Mine.

AREVA

By the end of this period, Namibia’s (mostly white and conservative) business community had come round to the idea of independence for three reasons: nothing else seemed to have worked; the white regime in South Africa, afflicted by even worse troubles, was in no position to help; and the few members of the newly-elected government they had met seemed to be reasonable men prepared to abandon the rhetoric of the past and deal pragmatically with the economy.

Once the country had actually won its independence, however, a rather different picture emerged. Wealthy members of the international community who had previously seemed enthused by the Namibian cause (and who, indeed, had jointly spent US$800 million on the year-long transition supervised by the United Nations) now lost interest. Faced with more interesting prospects in Eastern Europe, they were not disposed to be particularly generous to the newest – but by no means the poorest – member of the community of nations.

Oyster farmers at Shear Water Oysters, in Lüderitz.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

In short, the new Namibian government had to work very hard to attract grants and investment. Proximity to South Africa proved (and continues to prove) a double-edged sword: it is an advantage for export trade, but then South Africa tends to attract much of the aid and inward investment to the region. Aid donors meeting in New York in 1990 pledged funds totalling US$696 million to Namibia. Between two-thirds and three-quarters of this was promised in the form of grants, the balance in concessionary loans. Namibia’s proposal to the World Bank that it be regarded as one of the “Least Developed Countries” was, however, turned down, as its per-capita GDP exceeded US$1,000, the maximum for this category. Acceptance as an LDC would have given Namibia access to a wider range of concessionary bank funding.

Although it is a very large country – more than a third larger than the uk and Germany combined – Namibia is sparsely populated, supporting around 2 million people in 2010.

Communications

Namibia received US$600 million worth of aid as part of its 1996–2000 development plan from 30 donors under the United Nations Development Plan (UNDP). The UNDP describes the country as having “a stable political and economic climate and low tax rates. Namibia is well placed to serve as gateway to South Africa, boasting good communication networks and port facilities able to handle up to 800 vessels per day.” The EU is the largest contributor of aid to the region, while the biggest bilateral donors are Sweden and Germany.

Namibia is well served with major infrastructure: the main towns and cities are linked by some 5,450km (3,400 miles) of asphalt roads, while another 37,000km (23,000 miles) of gravel and unsurfaced roads traverse the rural areas of the country. Some 2,400km (1,500 miles) of railway lines, carrying both freight and passengers, are integrated with the South African rail network and thence with the rest of the subcontinent. More than 350 airstrips and airports, including an international terminal outside Windhoek, serve the national carrier, Air Namibia, smaller charter operations and private pilots.

Construction workers building the new viewpoint at the curve of the Fish River Canyon.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Two harbours – Lüderitz, a fishing port to the south, and Walvis Bay, a deep water harbour in the centre of the coast – provide access from the sea. Constitutional title to the Walvis Bay enclave was the subject of a long dispute with South Africa, which was settled amicably by negotiation in 1994.

Namibia produces up to 1.65 million carats per year – around 1.5 percent of world diamond production – which earns it around US$500 million of foreign exchange.

Mining, ranching and fishing

In African terms, Namibia is potentially rich – given its small population – with valuable mineral resources, exceptionally rich fishing waters and a strong livestock farming industry. Diamond, uranium and base metal mining, and beef cattle and Karakul sheep ranching have accounted for 90 percent of Namibia’s exports in the past, as well as about 40 percent of its GDP.

Namibia’s fishing grounds, in the nutrient-rich waters of the southeast Atlantic ocean, are some of the richest and least exploited in the world. Pelagic (pilchards, anchovies) and demersal (hake, white fish) species abound, and support a small, but thriving, rock lobster (crayfish) industry at Lüderitz. As Namibia’s 200-mile (320km) exclusive economic zone was not recognised before its independence and there was much pirate fishing, these waters have not yet provided the economic returns of which they are capable – with prudent management. The government believes that royalty payments by foreign fleets together with the value of local catches processed in Namibia could greatly increase revenue from this sector.

Livestock ranching on the southern and central plateau constitutes almost 90 percent of the value of Namibia’s agricultural output for commercial purposes. The agricultural sector itself contributes only about five percent of GDP, but almost 40 percent of the population is dependent on ranching and farming for their survival.

A Measure of Wealth

Based on the 2012 figure of US$12.46 billion, Namibia only ranks 25th in the list of African countries with the highest GDP. However, the country’s low population means that it fares far better in terms of per capita gross GDP, ranking 11th in Africa. Indeed, with a per capita GDP of around US$7,000, Namibia is officially regarded to be a low middle income country, a ranking undermined somewhat by its Gini coefficient (a figure based on comparative income of the wealthiest and poorest 10 percent of the population), which currently stands at 60, one of the world’s highest.

Almost 70 percent of Namibians depend on farming and ranching for their survival.

iStock

Poor rainfall in most of the country and cyclical droughts make crop cultivation impossible in the absence of irrigation. Even cattle ranching (which in Namibia means hardy beef species like the Brahman and the Afrikaner) can be precarious – the total cattle population has ranged from 1.3 to 2.5 million in recent decades, depending on climatic conditions. Most cattle sold commercially are transported by rail or truck to South Africa for slaughter, but the government maintains an annual export quota from the EU.

Changing trends

The pelts of Karakul lambs – once known as Namibia’s “black diamonds” – were traditionally auctioned in London, but since 1995 the twice-yearly sales have been held in Copenhagen, where the pelts are sold under the Swakara brand. Karakul farmers have been vulnerable to shifting fashions in the fur industry. At the peak of demand, there were 4 million Karakul sheep in the country and no fewer than 3 million Namibian pelts were sold in London alone, in a single year. Prices recovered only slightly after the collapse of the market in the early 1980s, only to crash again in 2001. Today, Karakul pelts create annual export earnings of around 5 million euros and the industry creates direct or indirect employment for about 20,000 people. Nevertheless, many farmers have shifted to joint wool/mutton production to protect themselves against the vagaries of the market.

As for minerals, the value of Namibia’s mining output ranks fourth in Africa, behind South Africa, the DRC and Botswana, and comprises on average over 75 percent of the country’s export earnings. The mining industry pays the bulk of corporate taxes and is the largest private sector employer – indeed, taxes and royalties from mining account for 25 percent of the national revenue. Little processing or beneficiation is undertaken in Namibia, however, and most of the products are exported; the industry is thus at the mercy of shifting market prices, reflected in volatile value added output. Employment levels in the industry have fallen in recent years and Tsumeb mine closed in 1998.

Trekopjie Mine near Swakopmund.

AREVA

Diamonds are mined from coastal deposits 30km (19 miles) off the coast of Lüderitz and on the Orange River – Namibia’s southern boundary – by NAMDEB. The corporation is owned in equal shares by the government of Namibia and De Beers, although the latter retains all exploitation rights. The production includes a high percentage of larger gems, although the average size is falling, and mining conditions are increasingly difficult. The lifetime of deposits depends on the results of new prospecting and the assumptions made about the depths at which it is possible and profitable to mine.

Media and Communications

The Namibia Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) offers radio programmes in nine languages, including English and German. Much of the country also receives a variety of TV programmes through the NBC, which will offer 21 digital channels to subscribers once the changeover to digital is complete in 2015. Electronic media lags behind the rest of the world, with around 30 percent of the population enjoying internet access in 2012. By contrast, the recent boom in mobile phone access has revolutionised communications in Namibia, with some the vast majority of adults now subscribing to fixed or mobile services.

Rössing Uranium, 68.6 percent owned by the British company Rio Tinto, together with a number of South African mining interests and Minatome of France, operate the world’s largest open-cast uranium mine 65km (40 miles) from Swakopmund (www.rossing.com). Careful financial structuring – including a lengthy tax holiday – and long-term supply contracts at high prices, concluded in the nuclear-friendly 1970s, enabled the mine to post excellent profits throughout the early 1980s despite the low-grade ore. A combination of circumstances has, however, since made the mine vulnerable. Uranium spot prices fell sharply as plans for nuclear reactors were shelved in the aftermath of the Three Mile Island (1979) and Chernobyl (1986) accidents and new, higher grade, deposits were developed in Australia and Canada. Political and legal pressures were also brought to bear on purchasers by the UN Council for Namibia.

As its long-term contracts drew to a close, Rössing had difficulties signing new agreements after independence in 1990. Uranium sales in the US were also inhibited in the few years before independence by the passage, at the end of 1986, of the Anti-Apartheid Act, which treated Namibia as part of South Africa. Although one new long-term contract was signed with the French EDF in 1990, a 25 percent production cut-back was announced by the Rössing board in 1991. Since then, Rössing has undergone a change in fortunes, and it now produces some 5 percent of the world’s uranium, making Namibia the fourth-largest producer globally. The Namibian government controls 51 percent of the voting rights and 3 percent of the equity in Rössing Uranium.

Most base (copper, lead, zinc, cadmium, pyrite, arsenic trioxide and sodium antimonate) and precious (gold and silver) mineral production used to be derived from four mines run by the Tsumeb Corporation (TCL), which closed in May 1998.

Namibia’s most important gold mine is Navachab, opened in 1989 near Karibib, and is operated by the multinational AngloGold Ashanti. It produces around 85,000 ounces of gold annually.

Zinc has been discovered in the south near Rosh Pinah and is bringing an influx of investment to the area around Lüderitz. Another key recent development was the discovery of vast offshore oil reserves in 2011.

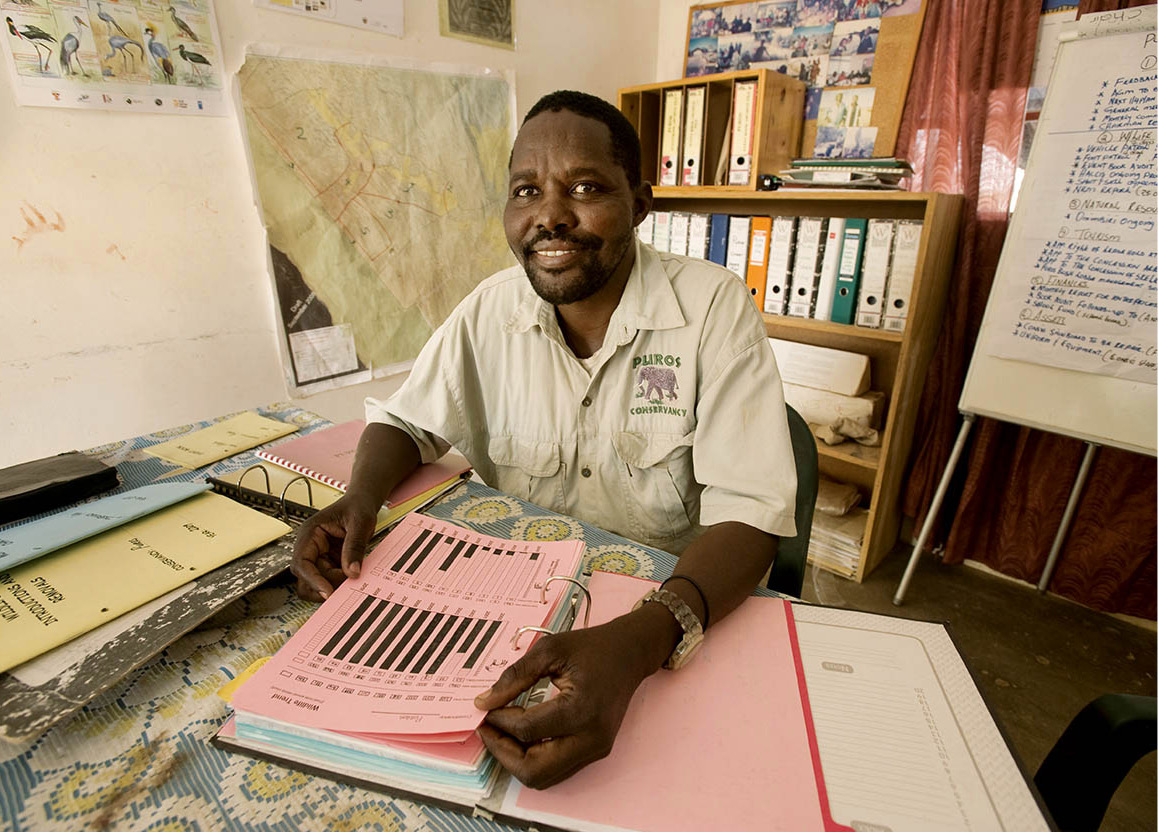

Wildlife Manager at Puros Village, Damaraland.

Corbis

Local manufacturing

Because South Africa administered Namibia pretty much as a fifth province until the end of the 1970s, there was very little scope or incentive for the development of local manufacturing industry.

At the time of independence, manufacturing contributed a mere 5 percent to GDP, but today that figure is more than 20 percent.

Many people now work in the food and beverage processing area. The government actively encourages domestic and foreign investment in this sector as a means to add value and create jobs. Unilever, Guinness and Lonrho are among the major companies to have entered the market.

Water and power

Although Windhoek has experienced a total population growth of almost 200 percent since the start of the millennium, most Namibians still lead a rural existence. Development of the physical and social infrastructure in the rural areas, particularly the more populated north, is thus a priority. The improvement of schooling and health care facilities and the provision of jobs, either on the land, or in small-scale, labour-intensive, informal manufacturing enterprises, requires electrification of the rural areas. Improved crop production and better use of grazing lands by livestock are dependent on the availability of water at points far removed from its sources.

Although most of Namibia is arid, the country has huge water resources within its borders, particularly in the north, where the Okavango system alone has more water than all the rivers of South Africa together. However, plans for the final phase of the Eastern Water Carrier, which would have brought water from the Okavango River to the centre of the country, were shelved in the 1980s due to lack of funds. Likewise, Namibia has the capacity to become the largest net gas exporter in the region through its gas deposits in the Kudu field in the Orange Basin.

Tourism has been and remains an important growth area, which now contributes more to the economy than the manufacturing sector. Direct flights to Europe, improved tourist facilities and increased travel to South Africa are all encouraging this trend.

South Africa is the country’s biggest trading partner. At one point, up to 90 percent of Namibia’s foreign trade was with South Africa, but while this is still the case for imports, around 70 percent of which are from South Africa, less than 20 percent of exported goods are now sold to the neighbouring republic. South Africa holds more than 50 percent of investments in the key sectors of banking, mining and insurance.

A construction worker in Walvis Baai (Walvis Bay).

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Challenge for the future

The country’s greatest strengths are the tolerance bred into the political culture since the mid-1970s, reinforced by its exemplary constitution; the free and active press; the basic health of the economy, despite its deficiencies; and the government’s pragmatic approach. Its weaknesses are high levels of unemployment; inequalities of income and opportunity between rural and urban areas and between black and white; over-dependence on the mining sector; insufficient industrial capacity due to an underdeveloped manufacturing sector; and a shortage of critical skills in key sectors of the economy and administration.

Deprived of the ideological shibboleths and divisive loyalties of the past, Namibians since independence have had the chance to unite in support of new social and economic programmes and give substance to the idea of nationhood. The challenges are enormous: combating unemployment, promoting rapid skills development and effecting economic restructuring to maintain growth, holding down inflation and reducing present inequalities of opportunity.

The end of the civil war gently boosted development in Namibia, the two countries co-operating to their mutual benefit. Angola is rich in minerals and energy sources and shares close cultural and ethnic ties with Namibia. Moreover, fruitful avenues are opening up toward regional co-operation – with South Africa as the economic motor of the region. In this way, the necessary progress can take place to enable Namibia to face the economic demands of the 21st century.

The uranium mine near Swakopmund.

AREVA