Africa, the melting pot of many different cultures and languages, is also a meeting-point of religions. Namibia is no exception and, when considering local traditions, there is no question of speaking about a single, unified religion. The country’s indigenous peoples have their own beliefs: for example, many vastly different taboos are observed by different Herero clans, while the Damara used to have many different names for their god.

Windhoek’s graceful Christuskirche (Christ Church).

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Despite this wide diversity of religious forms, one can perceive common threads among the colourful fabrics of the various indigenous beliefs. Virtually every one of them espouses the view that God created the world and has guarded it ever since. Certainly, various clans have given different names to the supreme being, and developed wildly differing conceptions of this god. But ultimately, all Africans are referring to the same God when they speak of the Creator and Guardian of the Earth.

The German missionary Heinrich Schmelen undertook the first translation of the New Testament into the Nama language, aided by his wife – herself a Nama.

In their countless myths, Namibia’s indigenous peoples also tell of the original link and covenant between God and Man, which was broken through some mistake committed by a man or a beast. But God did not cease to exist; his importance for the collective African peoples remained intact.

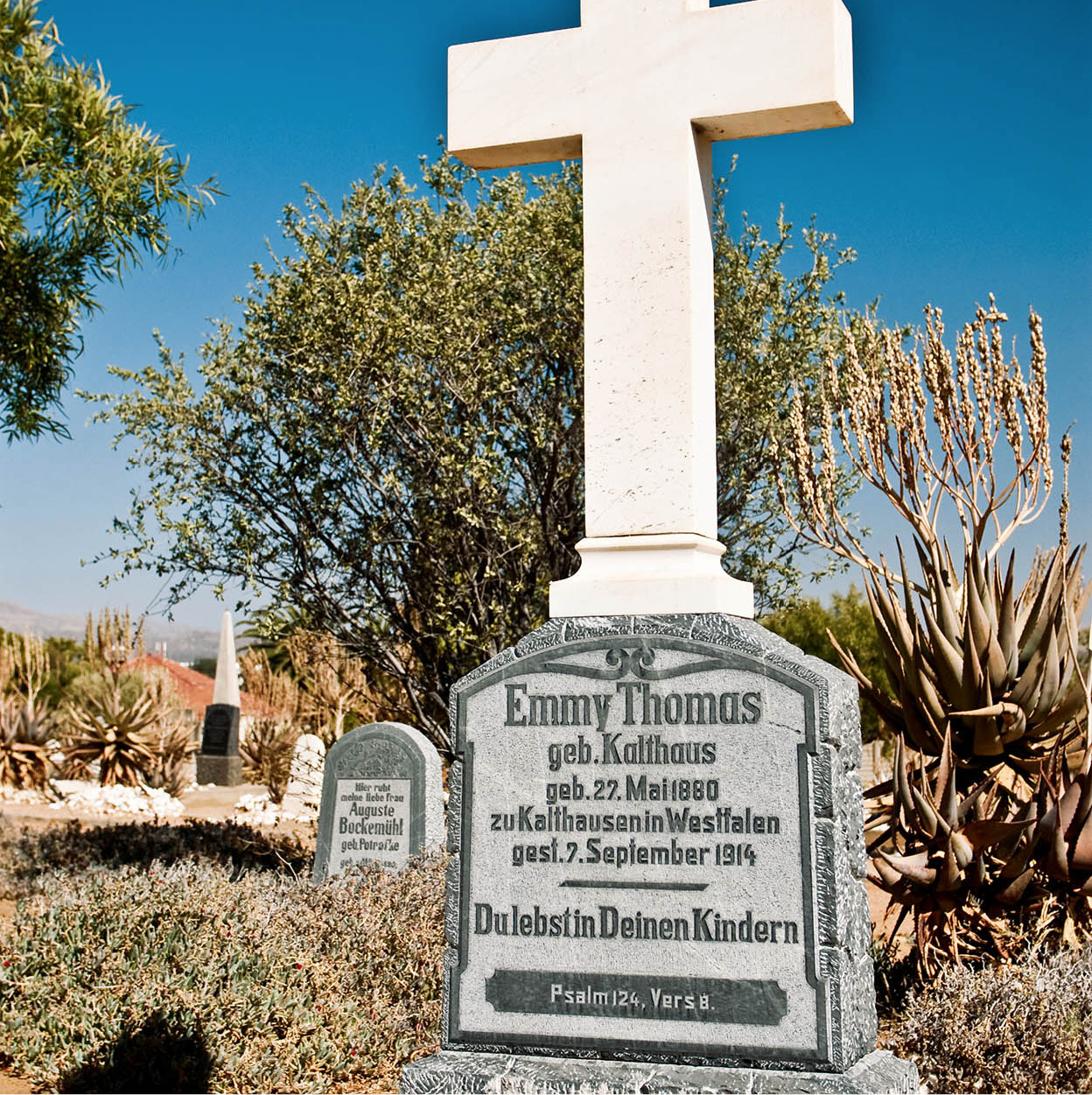

Leutwein Cemetery.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Missionary misapprehension

Time and again, Christian missionaries were astonished to find there were no formal religious services among the indigenous population; they took this as an indication of the lamentable degree to which heathen practices had spread.

But it was a mistake to make such judgements solely on the basis of European tradition. For in Africa, God is a being so holy and so thoroughly above Man that one hardly dares to speak his name aloud. If his name is uttered, it must be very guardedly – just as one is reluctant to disturb one’s king or chief with trivia or unimportant daily concerns. Men on earth contact the deity through the agency of beings nearer to him: the ancestors, more pithily termed “the living dead”. In traditional religion, the belief is that those who have died are not truly dead; they have taken on a new form of existence, but remain in contact with the living. They continue to belong to the family, even after their names have been forgotten.

A church in Windhoek.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

European missionaries were quick to conclude that “true worship” was displaced, in indigenous cultures, by this human “ancestor cult”. Again, this is to assess the situation in narrow European terms, leading to the wrong conclusions. For African traditions recognise no difference between the sacred and the profane; religion and daily life form a single unified whole.

Traditional religion today

“Official” statistics declare that around 91 percent of Namibia’s population is Christian. Only a small fraction of the population, it would seem, continues to observe traditional religious practices. Such traditionalists tend to be found more in the northern regions, among peoples such as the Himba in Kaokoland or the San people, or Bushmen. This fact demonstrates the zeal with which the missionaries pursued their goal: to introduce Christianity into every corner of the land.

Yet to conclude that the entire Namibian population follows Christianity as it is practised in the major churches of Europe would be false, for many old African traditions have permeated the Christian denominations.

Ancestors’ Memorial Day

This celebration of the Hereros is a fine example of this religious “co-existence”. Most indigenous traditions have, as a rule, remained closed to outsiders; but, in Namibia, the various Herero clans celebrate their national holiday with much fanfare and public display in Gobabis, Okahandja and Omaruru. While these festivities may not adhere strictly to the letter of religious law, both traditional and Christian elements are clearly evident.

In the case of Gobabis, events focus on a farm cemetery just outside town, where important chiefs and leaders of the East Herero (Mbanderu) are buried. For Nikodemus’ Day (named after one of the chiefs), Herero journey here from every corner of the land. If they arrive before sunset of the previous day, they must first visit the graves. Before doing this, their presence is made known to the ancestors, and they must undergo a test around the Ancestral Fire to determine whether or not their presence is also welcome to the ancestors. The cult priest pulls the visitor’s fingers; if a joint cracks, the candidate has passed muster. If not, he had better keep his distance.

For those admitted, there follows a ritual purification: a master of ceremonies sprays a mouthful of water over the guests. Now they may have access to the graves. At the entrance to the cemetery, the master of ceremonies kneels to the ground and introduces every visitor; through his voice, the ancestors command the petitioner to draw nearer. Each person kneels by the grave of the oldest chief, lays his hand on a stone and gives his name and place of origin. The other “living-dead” are greeted by touching their gravestone, or by laying small stones on the grave. Visitors can then move freely among the graves. On Sunday, this ceremony is repeated; then, gathered around the graves, worshippers hold a service as if in church.

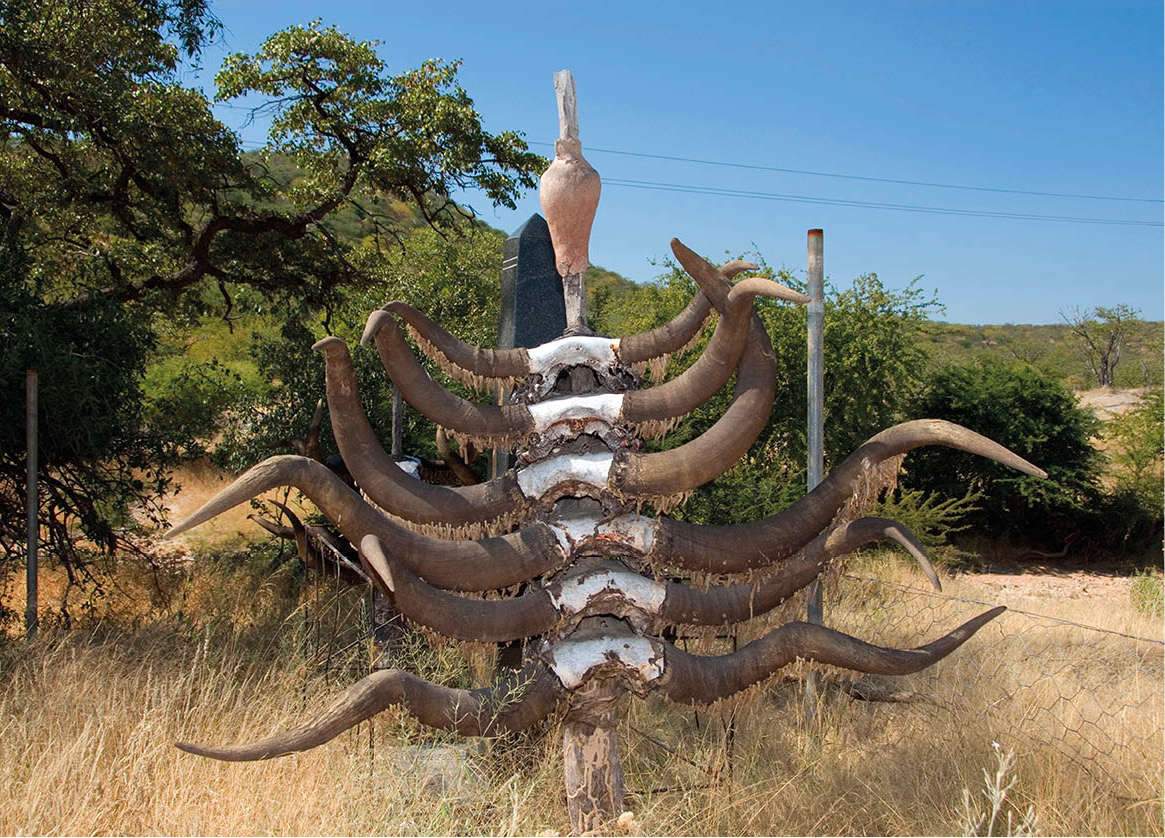

Traditionally, cattle skulls replace the Christian cross on Herero graves.

Photoshot

The thinking is that people’s sins determine the course of events. Anyone who has disregarded the commands and wisdom of the ancestors cannot have access to them. While Christianity concentrates on sins committed against God, the indigenous tradition addresses itself to the sins which men have committed against other men. It is for this reason that cooperation between the two traditions is seen as important.

Duality of Deities

At least two groups of San (Bushmen), the !Kung and the G/wi, traditionally believe in two “great chiefs” or gods. Yasema is the powerful god of good who lives in the east. He makes the sun rise, created all things and is the stronger god, on whom one calls for healing. Chevangani is the lesser god, who lives in the west, makes the sun set, and causes evil, sickness and death. When the Dutch Reform Church (ngk) began to work among the Bushmen in the 1980s, missionaries reported that, while the San had no problem in identifying Yasema with God and Chevangani with Satan, converts to Christianity were few.

The first missionaries

In 1805 the London Mission sent two German brothers, Abraham and Christian Albrecht, to Namibia to begin missionary work among the Khoi-khoi (Nama). Only someone who has crossed the dry, infertile regions in the south of the country will fully appreciate the difficulties they faced; indeed, in order to do their job and survive, they had no choice but to move with the nomadic Nama. Abraham died in 1810, but Christian continued their work, eventually establishing the first Christian community in Warmbad. In 1814 another London Mission-backed German missionary arrived in Windhoek. Heinrich Schmelen’s achievements were many: not only did he found a station at Bethanie (his one-room house can still be seen there today), but he discovered a new route west to the coast in the course of his missionary work.

Traditional healer at work.

Dreamstime

Variety of churches

It may sometimes seem to visitors that Namibia has churches at every turn. In fact, they fall quite neatly into three groups, one of which dates back to the missionary era. Originally nurtured by the Rhine Mission and the Finnish Mission, the Evangelical Lutheran Church has the largest following in this category today.

Then there are all those churches that developed when the white settlers came, such as the Roman Catholic Church, which also practises mission work – as does the Anglican Church – and the German Evangelical Lutheran Church.

The influence of the third group, the truly African, independent churches, cannot be judged by its church buildings alone: its congregations are based, for the most part, in black sections of the cities or on former reservations, where they remain unobtrusive and hidden. But if you pass through one of these areas on a Sunday, you will run across people singing, clapping their hands, or dancing around a candle in front of a house, under a tree, or in a simple room. It is not only priests and bishops who work here: prophets and charismatics do as well, while prayer healing and talking in tongues are seen as signs of the efficacy of the Holy Ghost. Song plays an important role even in the large communities of the former mission churches. No organ is needed; the congregation always sings in four-part harmony.

Islam in Namibia

A relatively recent presence in the country, Islam is now adhered to by an estimated 4,000 Namibians, most of whom are recent converts among the Nama, though there are also tiny enclaves of South African immigrants of Indian origin in some larger towns. The recent growth of Islam within Namibia was precipitated by the conversion of the Nama politician Jacobs Salman Dhameer at a 1980 conference in Lesotho. The country’s first mosque was built shortly afterwards in Katutura, a suburb of Windhoek, and there are now at least a dozen mosques countrywide, half of them in Windhoek.

Striving for unity

There is no question that the South African policy of apartheid also influenced church life in Namibia for years. The Catholic Church and the Anglican Church, at least, ignored the question of race and refused to segregate communities – unlike the South African Dutch Reform Church (NGK) – but on the whole their white adherents preferred not to align themselves directly with anti-apartheid action.

Under apartheid, the Lutheran Church split into three. Of the two ‘black’ churches, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (ELCIN) dominated in the north while the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Republic of Namibia (ELCRN) was more popular in the south. Most white Lutherans belonged to the German Evangelical Lutheran Church (GELK). After independence, unity proved to a elusive goal. Indeed, It was only in 2007 that the three Lutheran constituency formed the United Church Council of Namibia Evangelical Lutheran Churches, with the ultimate aim of becoming one national entity.

Bushmen performing a traditional trance dance.

Getty Images