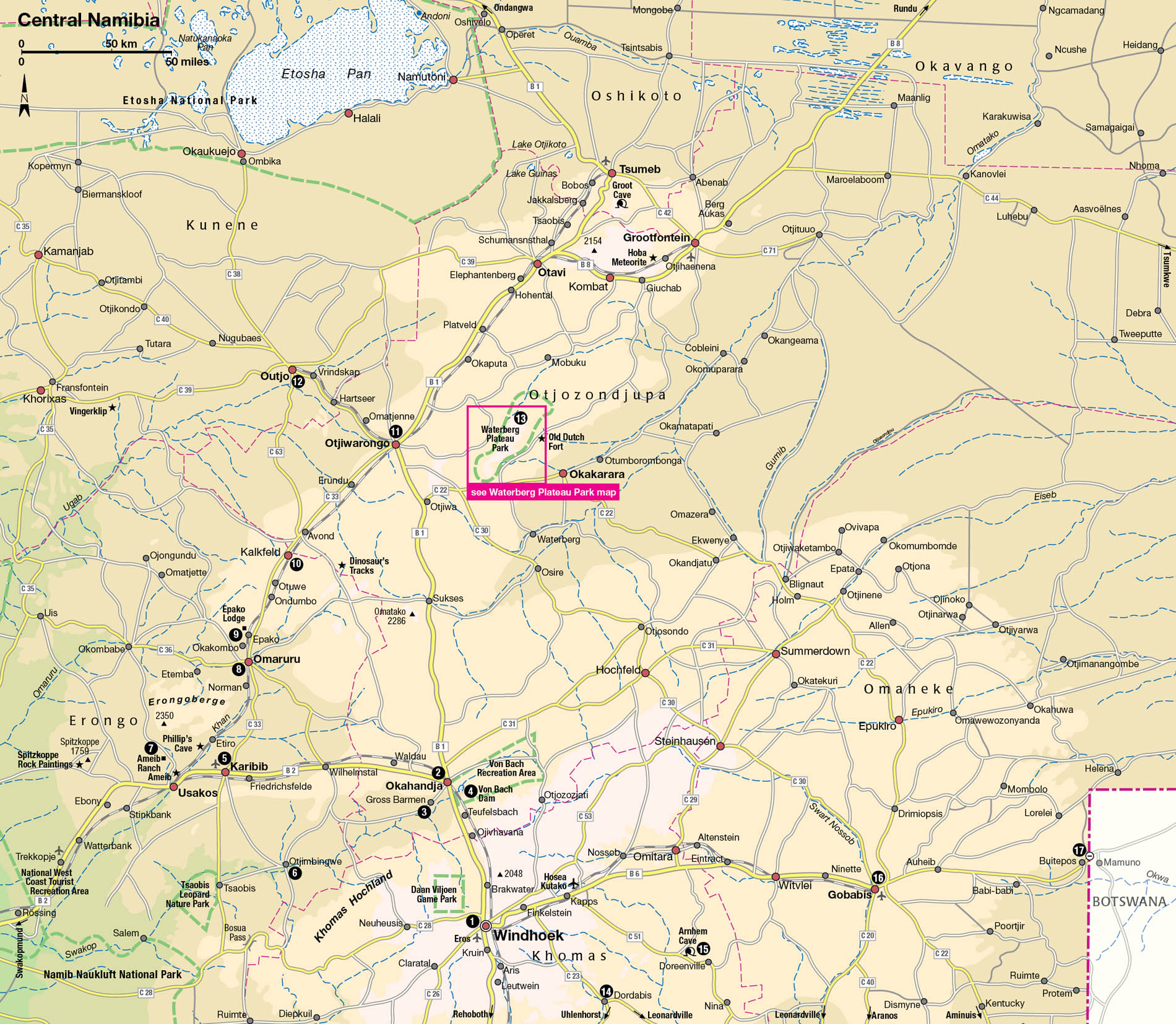

All too often, the area north of Windhoek is seen by visitors merely as something to “get through” en route to northern Namibia’s big draw, the Etosha National Park. Yet not only does north-central Namibia hold many attractions of its own which repay closer attention, it’s also well set up for a self-drive tour. Most roads are tarmac or well-graded gravel, while provisions, banking facilities and fuel are available at all the main towns and most rest camps along the way. Bear in mind, though, that many of the attractions round here are on private land, and require advance booking.

A safari camp.

Okonjima Lodge and the AfriCat Foundation

Exploring the highlands

Heading north from Windhoek 1 [map] on the B1 highway, you’ll pass through the hilly farmland of the Khomas Hochland, flanked on the east by the Onyati mountains. Okahandja 2 [map], 71km (44 miles) north of Windhoek, was founded by the Herero leader Tjamuaha c.1800. In 1827, the German priest Heinrich Schmelen became the first European to visit the town, leading to the establishment of a permanent mission in 1844. On 23 August 1850, nearby Moordkoppie (Murder Hill) was the scene of the massacre of 700 of Tjamuaha’s followers by their Nama rivals. This event instigated a seven-year war in which the Herero eventually conquered the Nama under the leadership of Tjamuaha’s son Maherero,

The German war cemetery, Waterberg Plateau.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

A Rhenish school was founded at Okahandja in 1870, and six years later the Rhenish Mission Church was consecrated. Situated on Kerk Street, this is now the oldest building in town, and several prominent figures including Maherero’s son William, the Nama leader Jonker Afrikaner, and the pioneering nationalist Hosea Kutajo – are either buried in the churchyard or in a separate cemetery opposite it.

Okahandja is the main Herero administrative centre, and a place of great historical significance for these people as a whole, too. The Green Flag Herero or Mbanderu assemble here each June to pay homage to their forefather, Kahimemua Nguvauva, executed in Okahandja on 13 June 1896 for his involvement in a revolt against the German administration. On Maherero Day, which falls on the last weekend in August, the streets come alive as the Red Flag Herero march to honour the memory of their fallen chiefs, the men in military-style uniforms, the women in billowing red dresses.

Lining the southern and northern approaches to the town are curio markets run by the Rundu-based Namibian Carvers Association, which are well worth a visit (daily). There’s also the Ombo Rest Camp (tel: 062 502003; www.ombo-rest-camp.com; small fee), 12km (7 miles) northwest of Okahandja on the C31, which doubles as a crocodile and ostrich farm, and offers 45-minute tours packed with facts about these two extraordinary creatures, which are respectively the world’s largest species of reptile and of bird.

Okahandja has a limited selection of hotels, but there is plenty of accommodation just outside town. Although this is some of the best farmland in Namibia – prime cattle-ranching country, in particular – in recent years many farmers have restocked their land with game and opened up as guest farms catering for the tourist trade.

Apart from these, other good stopover places in the vicinity include Gross Barmen 3 [map] (tel: 062 501091; www.nwr.com.na; daily), another old mission station built round a dam on the Swakop River some 24km (15 miles) southwest of town on the C87. The main attraction here is a hot mineral spring, feeding a glass-enclosed thermal hall and an outdoor swimming pool. The water has a constant temperature of 65°C (150°F), but is cooled to a more bearable 40°C (104°F) for the thermal pool.

Closed for renovations in 2014, the spa has always been popular with weekending locals and visitors passing through en route to Etosha, and there are also some excellent walks and birdwatching in the surrounding wooded hills.

Stocked with carp, bream, barbel and bass, Von Bach Dam 4 [map] (tel: 061 400 205; www.tungeni.com), which lies just off the B1, some 3.5km (2 miles) south of Okahandja, is a big hit with water sport enthusiasts and fishermen. Game-viewing opportunities are limited, but kudu, Hartmann’s mountain zebra, springbok, eland and ostrich are all present in the surrounding park. There’s also a recently privatised and renovated resort on the lakeshore.

Outside Okahandja, the B2 turns off in a westerly direction to the coastal resorts of Swakopmund and Walvis Bay. Take this road and at first you’ll pass through predominantly featureless bush farmland before the ochre-pink granite mass of the Erongo mountains come into view in the north, just outside Karibib 5 [map]. This little ranching town (112km/70 miles from Okahandja), is best known for its high-quality marble produced at the Marmorwerke quarry nearby; examples can be seen on floors in the Houses of Parliament in Cape Town and even on wall panels at Frankfurt Airport.

The useful Henckert Tourist Centre (38 Hidipo Hamutenya Road; tel: 064 550700; 8am–5pm Mon–Fri) should be your first stop here; it began as a gem and curio shop back in 1969 but now houses a modern tourist information facility, a money bureau and a coffee shop too.

From Karibib, you can take a detour south to Otjimbingwe, or continue 30km (18 miles) along the B2 to Usakos to visit the Ameib Rock Paintings. Sleepy Otjimbingwe 6 [map] lies 51km (32 miles) along the D1953; founded as a Rhenish mission station in 1849, it remained a quiet little place until the early 1880s when – thanks to its strategic position halfway between Windhoek and Walvis Bay – it enjoyed a brief stint as German South West Africa’s administrative capital. In 1890, however, the capital was transferred to Windhoek, and Otjimbingwe sank back into small-town torpor once more. It does have some interesting buildings, however, including the Rhenish church (the oldest place of Christian worship for the Herero, built over 1865–7), and the 1872 powder magazine erected to protect the locals against Nama attacks.

Wood carving in Okahandja.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

The Erongo massif is best known for its rock art sites, of which the vast Phillip’s Cave – home to a famous engraving of a “white elephant” – is the most rewarding. It’s situated on land belonging to an upmarket guest farm, the Ameib Ranch 7 [map] (tel: 081 857 4639; www.ameib.com), lying some 27km (17 miles) from Usakos: to get there, take the D1935 for 11km (7 miles) before turning right on the D1937. The cave is a short drive and then a 40-minute walk from the ranch house. There are also several good walks to the curiously-shaped rock formations scattered around the farm, too – the group of round granite boulders known as the Bull’s Party, some 5km (3 miles) from the house, is one of the most picturesque.

Fact

In Namibia, rock art has mainly been created by the Bushmen. It is almost impossible to date the rock paintings by radiocarbon as the materials used for the paintings are inorganic.

Back in Karibib, it’s a 65km (40-mile) drive north through undulating bush farmland to pretty little Omaruru 8 [map] on the C33. Set on the banks of the Omaruru River – dry and sandy for the best part of the year – this former Rhenish mission station came under repeated attack by Herero forces at the turn of the last century and in 1904 was finally besieged. But the day was saved by a German officer, Captain Victor Franke, who petitioned the then Governor for permission to march north with his company from their garrison in southern Namibia and lend their efforts to the fight. After a 19-day trek, he galloped into Omaruru and relieved the siege. Franke Tower on Omaruru’s eastern outskirts was built in his honour; it’s usually kept locked, but ask at the nearby Central Hotel if you want to get hold of a key.

Fact

In Herero, Omaruru means “sour milk”, after the milk their cows gave when they’d been grazing on a local shrub, known as the bitterbush.

If you’re keen to see more rock art, there’s a very well-preserved site with both paintings and engravings outside Omaruru on a farm owned by the Hinterholzer family. Follow the D2315, 3km (2 miles) south of Omaruru for 24km (15 miles) and then turn south on the D2316 for 19km (12 miles). Allow approximately an hour to reach Erongo Lodge (not to be confused with the Erongo Wilderness Lodge). It’s a short drive to the site from here, along a road that climbs steeply into the thinly-wooded hillsides of the Erongo Mountains, past white-trunked moringa trees striping the ochre rock faces. Visiting arrangements can be made through Erongo Lodge (tel: 064 570852; www.erongolodge.iway.na).

The road to Etosha

Like Okahandja, Omaruru is well served by guest farms, many of which stock game. Luxurious Epako Lodge 9 [map] (for more information, click here), 18km (11 miles) north on the C33, is a particularly good stopover choice if you don’t have time to visit Etosha – the wildlife here includes elephant, leopard, white rhino and giraffe, as well as over 180 species of bird. It also has some rock art, although the paintings aren’t of the same quality as those found near Erongo Lodge.

Keep going north along the C33 for some 64km (40 miles) from Omaruru and you’ll reach the village of Kalkfeld ) [map]. The only reason for stopping here is to visit the fossilised dinosaur tracks on the nearby (and extraordinarily named) Otjihaenamaparero Farm (tel: 067 290153; www.dinosaurstracks.com; daily; charge). The most striking imprints here, made by a two-legged, three-toed dinosaur can be followed for about 25 metres (80ft). From Kalkfield, follow the clearly signposted D2414 southeast for about 25km (15 miles), then turn left into the D2467 and follow it for another 1.5km (one mile) to a parking area, from where it is a short walk to the tracks.

A 70km (43 miles) drive northeast from Kalkfield leads to Otjiwarongo ! [map], a rather unremarkable ranching town that has adequate tourist facilities and serves as a popular springboard for eastern Etosha and the Waterberg. The only attraction in the town centre is the Otjiwarongo Crocodile Ranch (tel: 067 302121; daily 9am–4pm; charge), a CITES-registered facility that breeds crocodiles for their skins, which are exported to make shoes, handbags and other goods, and also has a small café serving crocodile steaks and snacks.

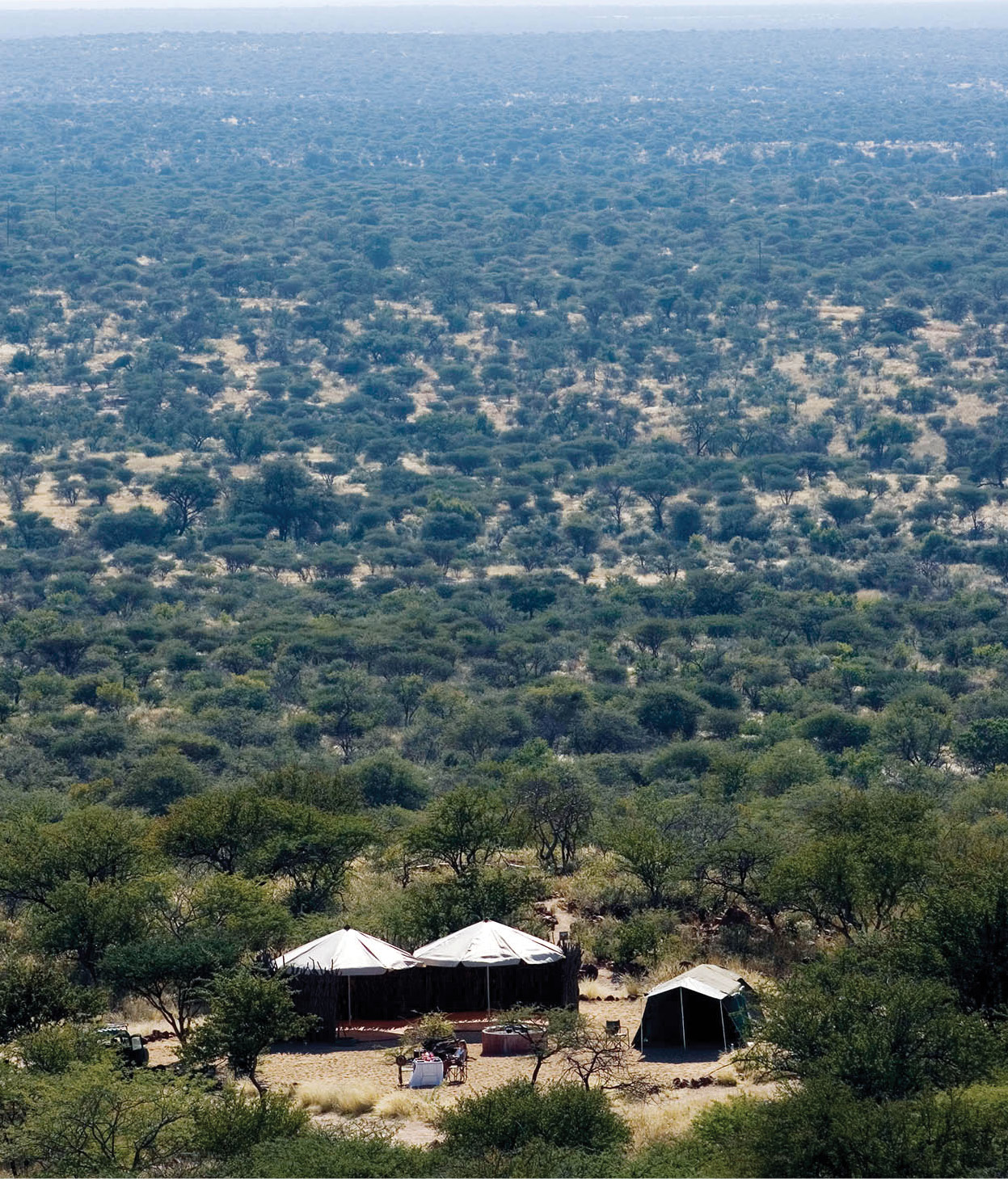

A more popular stop-off than the town itself is the guest farm called Okonjima, which is signposted west of the B1 trunk road about 35km (22 miles) south of town. Serviced by several luxury lodges and a camping site, this vast and in parts mountainous acacia-studded farm is also home to the AfriCat Foundation (www.africat.org), whose pioneering work in the rescue and release of big cats has earned it numerous international ecological and ecotourism awards since it started operating in 1997.

A cheetah stares into the lens.

Okonjima Lodge and the AfriCat Foundation

A one- or two-night stopover at one of Okonjima’s exceptionally comfortable lodges is the ideal way to break up the drive from Windhoek to Etosha, while also offering some superb close-up encounters with habituated leopard, captive lion and rehabilitating cheetah. Ask to be shown around the clinic and information centre for further insight into this multi-faceted organisation, which rescues an average of 70 “problem” cheetahs and leopards annually, and has been able to release more than 85 percent of these handsome creatures back into the wild. AfriCat also plays an important role in educating youngsters about big cats (tens of thousands of children and young adults have passed through its education centre or outreach programme since 1998) whilst also giving refuge to “welfare” animals which for one or another reason cannot safely be released back into to the wild.

Outjo @ [map], a further 68km (42 miles) northwest of Otjiwarongo along the C38, is an attractive little place set amidst low, grassy hills (the name means “small hills” in Herero) with views of the Paresis mountains. It was first established in 1897 as a Schutztruppe control post, although development pretty much ceased during the Herero War (1904–5). There’s not really much to see here although, as it is just 96km (60 miles) from here to Etosha’s Andersson Gate, it could serve as a good overnight stop if you’re heading on to the park.

Waterberg Plateau National Park

The jewel of central Namibia, situated about 100km (60 miles) east of Otjiwarongo, is undoubtedly the Waterberg Plateau Park £ [map]. An island of red sandstone cliffs lushly thatched with green, rising majestically above the surrounding savannah, the park was proclaimed in 1972 as a sanctuary and breeding-ground for threatened species such as white rhino, roan and sable antelope, and tsessebe. The scheme has been very successful, with some species now being translocated to other areas. Other animals you might spot here include leopard, brown hyena and caracal, together with over 200 bird species, from the rare Rüppell’s parrot and Verreaux’s (black) eagle to Namibia’s only breeding colony of Cape vultures.

This is not a park for self-drive tours. Instead, you can explore the nine short nature walks which have been laid out around the camp area, or book yourself onto one of the organised game drives which the park operates twice a day, visiting hides and waterholes. But perhaps the best way to experience the park’s diverse landscapes – from woodland and grassland to thick acacia bush – is by joining one of the four-day organised wilderness trails which run in the dry season (between April and November), where you follow game trails with a qualified guide, and learn about ecology and wildlife issues.

Waterberg Camp (formerly Bernabé de la Bat Rest Camp; www.nwr.com.na) has accommodation in pink sandstone bungalows spread along the plateau’s wooded slopes, along with a restaurant and shops, a petrol station and swimming pool. To reach the park from Otjiwarongo, it’s a 27km (17-mile) drive south on the B1, followed by 58km (36 miles) east on the C22, before turning north onto the D2512 for 17km (10 miles).

The pools at Waterberg Park.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

East of Windhoek

Compared to the rest of the country, central Namibia’s eastern section has relatively few tourist attractions. The main draw here is the region’s tranquillity and unspoiled scenery – striking camel-thorn savannah vegetation on red Kalahari sand. It’s best explored on a day trip from Windhoek, or as part of a route south following the fringes of the Kalahari to Mariental or Keetmanshoop via the C15 and C17.

Precious Pelts

Soft, smooth, silky and supple, Karakul pelts are “Namibia’s Persians”, and the carpets and coats made from them fetch a high price both at home and abroad. Dordabis in the eastern part of Central Namibia is the heart of the Karakul industry; in these dry lands on the fringes of the Kalahari Desert, the hardy Karakul sheep enable many people to make a living where it might otherwise be impossible. The sheep’s grazing habits stimulate the growth of many local plants and shrubs, while by treading grass stems into the ground, the herds also prevent erosion; the top level of soil, usually endangered by the wind, is thus saved.

There’s only one thing that neither man nor beast can force from nature: rain. When there’s a drought in these already arid regions, it has dire consequences on the Karakul industry. Lack of food and water drastically cut down the size of the herds.

The first sheep were imported from Germany in 1907; there are now over 1 million in Namibia, bred in black, grey, brown and white. In 1978, some 2,500 Karakul breeders produced 4.66 million pelts. Drought and reduced demand pushed the industry into decline in the 1990s, when production dropped to 120,000 pelts annually. More recently, while volumes remain low by comparison to the 1970s, a sharp rise in prices has done much to resuscitate the industry.

Karakul pelts strung out to dry.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Pretty little Dordabis $ [map] surrounded by rounded hills, is the centre of Namibia’s Karakul industry, and farms have workshops offering rugs and wall-hangings for sale. One of the best to buy from is Ibenstein Weavers (tel: 062 573524; www.ibenstein-weavers.com.na), 3km (2 miles) south of Dordabis on the C15.

Other attractions include the Arnhem Cave % [map] (tel: 062 581885; open daily, charge), the longest cave system in Namibia with a total length of 4.5km (3 miles). An underground trail takes you past various kinds of mineral deposits and six bat species – including the giant leaf-nosed bat (Hipposideros commersoni), one of the world’s largest insectivorous bats. As the cave is dusty, old clothes and a good torch are required. There’s a small rest camp here, too.

To get there, take the B6 from Windhoek to the airport. Follow the D1458 southeast for 66km (41 miles), then turn north on the D1506 for 11km to a T-junction, when you should turn south onto the D1808 for 4km (2.5 miles).

Busy Gobabis ^ [map], 200km (124 miles) east of Windhoek on the B6, is a cattle-ranching centre and – with the border at Buitepos & [map] just 120km (190 miles) east – the main jumping-off point if you’re heading east to Botswana.

The Nama possess a natural affinity with music.

Andy Selinger/fotoLibra

The Nama

Of slight build and delicate features, the Nama are the most populous surviving ethnic group to speak one of Africa’s ancient click-based Khoikhoi languages.

The Nama form a subgroup of the indigenous Khoikhoi (previously referred to by the derogatory term “Hottentots”). Most Khoikhoi within the boundaries of Namibia belong to the Nama and Oorlam groups. Their original territory was centred on the Orange River, along the border with South Africa, but over the course of the 19th century, a rapidly advancing white farming community pushed them continuously northwards.

Led by Chief Jan Jonker Afrikaner, the Nama settled in the vicinity of Windhoek and Okahandja in the mid-19th century, where they soon came into conflict with the Herero who already inhabited the area. Setting aside past differences, however, the Nama, led by the septuagenarian Hendrik Witbooi, a grandson of Jonker Afrikaner, joined the Herero in taking up arms against the Germans in 1904. It is estimated that around 10,000 Nama – half of the entire population at that time – died over the next three years, many of them children and women interned in concentration camps.

Internecine quarrels in the past and wars against the advancing intruders brought great suffering to the Nama; under the South Africans their living space was confined to a number of so-called reserves. In spite of their heroic resistance against colonialism and strenuous efforts to preserve their identity, their culture has been greatly eroded. But their heroes still live on in tales and praise poems of chiefs and other prominent personalities.

Certain distinctive features make the Khoikhoi easily recognisable. The women’s small and slender hands and feet are the subject of traditional praise poems. High and prominent cheekbones combined with a tapering chin and markedly platyrrhine noses add to the general flatness of the facial profile. Faces are animated by beautiful dark eyes which seem to be almond-shaped on account of a particular fold of the upper eyelid. In common with the Bushmen, the women have an extraordinary accumulation of subcutaneous fat over the buttocks.

The present-day Nama population numbers around 100,000. As pastoral nomads, the Nama traditionally had little need of permanent structures – their beehive-shaped rush-mat houses were perfectly suited to their lifestyle. The concept of communal land ownership still prevails among most clans today, except for the Aonin or Topnaars, whose fields are the property of individual lineages.

Nama tribes at the coast have always considered the sea an important source of food. Occasionally the people have taken to gardening and, in a small way, even to agriculture. Recently, communal agricultural projects have been established at Hoachanas, Gibeon, Berseba and other places.

A tribe of music and poetry

While their decorative art is somewhat poorly developed, the Nama possess a natural talent for music and poetry; no visitor to a Nama village at Sesfontein valley will easily forget the soft, lilting sounds of reed-flutes on a moonlit night. The literary talent of the people, meanwhile, expresses itself in prose and verse. Numerous proverbs and riddles, tales and poems have been handed down orally from generation to generation, while several hundred folk-tales are known and still told – some with as many as 40 different versions.