Inland from the desert plain of the Skeleton Coast rises an austere and rugged wilderness, one of the last real wildernesses in Africa. Although it falls within the Kunene and Erongo regions, it’s still commonly referred to by its old names, Kaokoland (for the northern region) and Damaraland (for the south). Home to a unique flora and fauna as well as some hauntingly beautiful scenery, this wilderness is the least-populated part of Namibia. Damaraland’s the ancestral home of the Damara people, while in the far north live the Himba, semi-nomadic pasturalists whose lives centre around their cattleherds.

Perfect equilibrium.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

A desert rich in wildlife

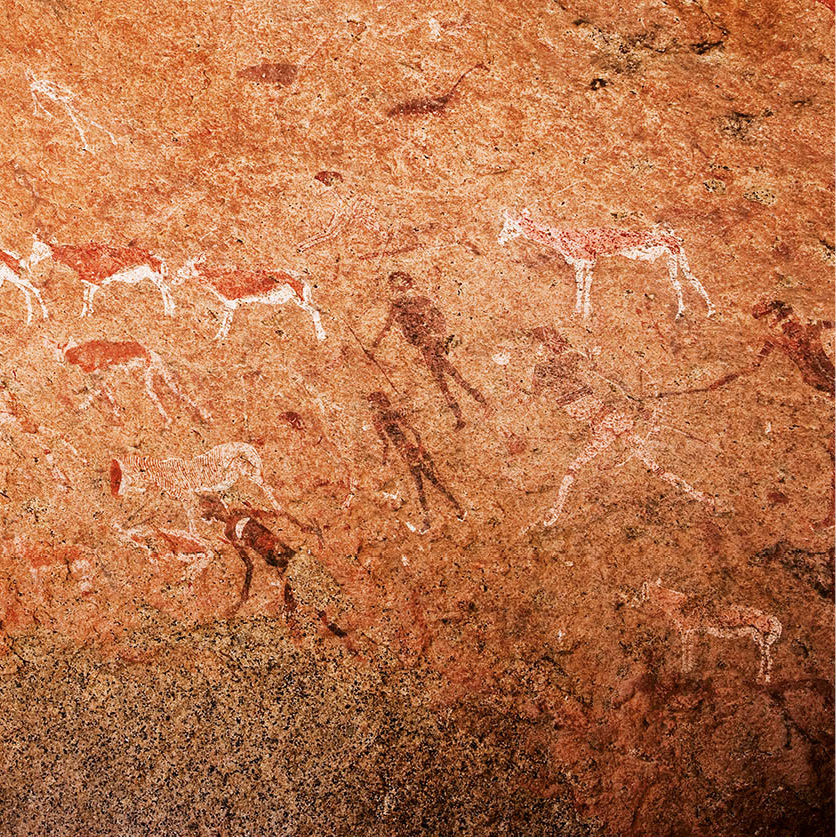

As the rock paintings in Damaraland’s Twyfelfontein valley illustrate, wildlife has survived in this parched land for thousands of years. Today, rare desert elephants and black rhino forage alongside scattered sand-rivers such as the Hoanib and the Hoarusib, while nomadic herds of game including kudu, oryx and Hartmann’s mountain zebra roam the north and the east, where the vegetation’s more dense. A rich and varied birdlife – from near-endemic species such as the Herero Chat and Rüppell’s korhaan to the ostrich – and a host of curious plants such as the commiphora and the Welwitschia mirabilis (a sort of underground tree) also eke out an existence in these seemingly barren wastes.

Heading into Namibia’s northwestern wilderness.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Although most of the main sights in southern Damaraland are accessible in an ordinary car, a 4x4 is essential in Kaokoland or if you plan to explore away from the main highway in northern Damaraland. In Kaokoland you should always travel in convoy with a minimum of two 4x4 vehicles, carrying extra fuel and water, comprehensive maps and a gps navigation aid (though roads may be marked on the map, in practice some simply don’t exist).

Given these conditions, by far the safest and most interesting way to experience the area is to travel with a specialist tour operator and knowledgeable guide, who can give an insight into Kaokoland’s fascinating plants, wildlife and cultures.

Southern Damaraland

Nondescript Khorixas 1 [map], the former administrative capital of Damaraland, is 131km (81 miles) due west of Outjo on the C39 and well placed as a base for exploring the south and for stocking up on supplies. Otherwise, there’s not much to see here, although the Khorixas Community Craft Centre – a project backed by the Save the Rhino Trust – at the entrance to the town is definitely worth a visit if you’re interested in good-quality crafts. Note, however, that the craft centre may eventually be relocated following the town council’s 2013 announcement that it may be build in new shopping mall on the site.

Follow the C35 south towards sleepy Uis Mine 2 [map], which initially evolved around a small tin mine (now closed). Just beyond the town – some 105km (65 miles) from Khorixas – turn west onto the D2359 and follow it for 28km (17 miles) to the Brandberg 3 [map], an oval-shaped massif which towers above the surrounding plains. Around 120 million years ago there was a volcano here, set in a rocky plateau. Gradual erosion of the plateau’s own lava-layers has exposed this giant chunk of weather-resistant granite, whose 2,573-metre (8,440 ft), summit, known as the Königstein (German for King’s Stone) is the highest point in Namibia.

The “White Lady”

The most celebrated rock painting in Namibia is the 40cm (16in) -tall humanoid first described in the 1950s by the French archaeologist Abbé Henri Breuil, who named it the “White Lady of the Brandberg” . Breuil theorised that the white pigment indicated that the figure (which he thought was female) depicted a person of Mediterranean origin, an idea that was popularised by apartheid theorists as proof of an ancient European influence in the region.

The “White Lady” theory is now utterly discredited by respected rock art experts, who recognise the figure to be that of a male hunter or tribal shaman – and to be no more European in origin than are the elephants and other animals painted in white pigment on rocks elsewhere in Namibia.

The White Lady, amongst other figures.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

The German name Brandberg (“Fire Mountain”) refers to the burnished glow of this granite extrusion before sunset. The same phenomenon is alluded to in the Damara name Daures (“Burning Mountain”). The Herero call it Omukuruvaro, the “Mountain of Gods”. Long before that, for thousands of years, nomadic hunter-gatherers sheltered in the myriad caves and overhangs of the Brandberg, as evidenced by the prolific ancient rock art that adorns the walls. The richest seam of rock art sites, comprising more than 40,000 individual painted figures, is to the northeast near the Tsisab Ravine, where you can see a painted frieze featuring the so-called “White Lady of the Brandberg” – a sweaty three-hour return walk, so avoid setting out in the heat of the day. There are at least 17 other rock-painting sites within a 1km (1-mile) radius of the White Lady, most of which depict big game such as lion, giraffe and ostrich. Guides from the local community can be hired if you want to explore the area more thoroughly.

Tip

You need a permit from the NWR (Namibia Wildlife Resorts) office in Windhoek (www.nwr.com.na) if you want to visit the spectacular Doros Crater near Twyfelfontein.

South of Uis is the dramatic Spitzkoppe 4 [map], a pyramid-shaped mountain known as the “Matterhorn of Namibia” which offers several more rock-art sites and some good walking trails to boot. To reach it from Uis, take the C36 Omaruru road for 1km (1 mile) before turning south on the D1930 for 76km (47 miles), followed by the D3716. The site is run communally from the village of Spitzkoppe (tel: 081 211 6291 www.spitzkoppereservations.com; sunrise–sunset; charge), which can arrange knowledgeable local guides and runs a small guesthouse with camping sites and bungalows.

Around Khorixas

Just east of Khorixas is another famous local landmark, a slender 35-metre (115ft)-high monolith known as the Vingerklip 5 [map] (“rock finger” in Afrikaans). Take the C39 for 46km (29 miles), followed by the D2743 for about 21km (13 miles) to reach this spectacular limestone pinnacle, poking up from the surrounding flat-topped terraces like something from a science fiction movie set. It’s a favourite haunt of rock kestrels, too.

The equally odd-looking Petrified Forest 6 [map] – a collection of fossilised logs that have been estimated to be between 240 and 300 million years old – lies about 42km (26 miles) west of Khorixas along the C39. Remnants of at least 50 trees can be seen, some partially buried in the surrounding sandstone. A guided tour takes about an hour (the site’s open daily; small charge).

The biggest attraction around here, though, is the boulder-strewn hillside known as Twyfelfontein 7 [map] (8am–5pm; charge), lying just southwest of the Petrified Forest. Inscribed as Namibia’s first Unesco World Heritage Site in 2007, this is widely considered to be one of the richest rock-art sites in Africa, with more than 2,000 rock engravings and paintings, some dating back to before 3300 bc, depicting various animals and their spoor, as well as people. Local guides will lead visitors along the two trails that run uphill from the parking lot, past the “Doubtful Spring” after which Twyfelfontein is named, to a hillside scattered with about a dozen engraved or painted panels. Named after two of the more striking engravings on display, the Dancing Kudu and Lion Man Trails each take about one hour to walk, inclusive of stops to admire the artwork and the views, and they could be covered together in about 90 minutes. Climatically, the most comfortable time to visit is early morning, shortly after the gates open, but this is also when the site is busiest – for a more peaceful perusal, try visiting at around 4pm.

To reach Twyfelfontein, follow the C39 from Khorixas for 73km (45 miles) before turning onto the D3254 for 36km (22 miles). There’s a community-run campsite at nearby Aba-Huab, and a couple of fine upmarket lodges too.

A geological feature referred to as “organ pipes” in the Brandberg Mountains.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Other attractions worth visiting around here are the Organ Pipes, a mass of perpendicular dolerite slabs thought to be between 130 and 150 million years old (they’re about 10km or 6 miles east of Twyfelfontein on the D3254), and nearby Burnt Mountain 8 [map]. This range is pretty uninspiring when the sun is high but turns into a glowing kaleidoscope of colour – red, orange, grey and purple – when its shale slopes reflect the early morning and late afternoon light. Southeast of Twyfelfontein, meanwhile, are the equally dramatic Doros and Messum Craters, both of which can only be reached with a 4x4 vehicle.

People on foot in Damaraland hoping to see a rhino or elephant!

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Northern Damaraland

The further north you travel in Damaraland, the more the route begins to take on an expeditionary feel. The scenery becomes more rugged and austere, sand dunes encroach upon the road, the sun blazes down and one can travel for miles without seeing a single soul. However, the government has set aside several large tracts of land around here for tourism (each allocated to different operators) and, although development is controlled, the region is reasonably well supplied with private lodges and camps. Prior booking is required for the community-owned (but privately managed) Damaraland Camp and Desert Rhino Camp, both of which have a collection point for those arriving by saloon car. Situated on the edge of the concessions alongside the C34, Palmwag Lodge is accessible in an ordinary saloon car and open to casual visitors (for more information, click here).

The main draw around here is the wildlife, especially the desert-adapted elephants and black rhinos, although the latter are seldom seen outside the Palmwag Concession operated by Desert Rhino Camp. Most camps offer game drives and guided walks into the heart of the terracotta-coloured mountains where you could also spot gemsbok, kudu, springbok, mountain zebra and a splendid range of birds including the black eagle. If you’re determined to see a desert rhino, tracking trips into Palmwag leave daily from Desert Rhino Camp.

From Palmwag, it’s 118km (73 miles) to little Kamanjab 9 [map], near the western approach to Etosha. This is a useful place to stock up on fuel and essential supplies, although there’s not much else to stop for and only one place to stay. Fortunately, there are a number of lodges and guest farms in the vicinity, among them Hobatere and Huab lodges which are both on large private reserves (for more information, click here).

From Palmwag, it’s 91km (56 miles) on the D3706 to Damaraland’s northern boundary and the sprawling Herero settlement of Sesfontein ) [map]. Literally translating as “Spring Six”, and scattered with picturesque fan palms (Hyphaene petersiana), Sesfontein has something of the feel of a desert oasis, especially after a long, dusty drive. It was a strategic military outpost for the German colonial government in the late 19th century, and the main monument from that period, Fort Sesfontein (1896) has now been renovated and turned into a hotel. Also oasis-like in feel, Ongongo Campsite (tel: 081 211 6291, www.spitzkoppereservations.com) set around a large natural rock pool and waterfall on the upper reaches of the Hoarusib River, lies to the east of the Palmwag Road some 18km (11 miles) Sesfontein.

Local transport just outside Upowo.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

The Damara

The unsolved mystery of how a distinct ethnic group first came to Namibia fascinates historians and scientists to this day.

The Damara comprise only about 7.5 percent of Namibia’s population, but they are probably one of its oldest ethnic groups. The existence of a very dark-skinned group of Negroid hunter-gatherers in this region, speaking a dialect of the click-based Khoekhoegowab language of the Central Khoisan, has for a long time aroused special interest both among scientists and the general public. The people themselves have no clear oral tradition relating to their origin and ancient history prior to arriving in their present-day homeland, and while a number of hypotheses have been postulated – most credibly that they migrated here from West Africa several thousands of years ago – the mystery is unsolved.

Traditionally, the Damara consist of 23 clans (haoti), each governed by its own chief, all of whom are subservient to the paramount king. Since 1994, this has been King Justus Garoëb, who became acting king 12 years earlier, and has also played a prominent role in national politics, as leader of the anti-apartheid Namibia National Front in the late 1970s, founder of the United Democratic Front in 1989, and a three-time presidential candidate.

In pre-colonial times, the Damara populated an extensive area from the Khuiseb River up towards the Swakop River; in the central parts from Rehoboth and Hochanas to the Khomas Highlands, west of Windhoek; and especially in the area where they are presently concentrated – northeast of the Namib around Outjo, Kamanjab, Khorixas and Brandberg.

Damara reservations

About two centuries ago, the Damara began to be ousted from their traditional areas by advancing Nama and Herero, the latter hunting them down and either killing them or carrying them off as slaves. Finally, at the request of the Rhenish Missionary Society, the Herero chief Zeraua ceded the Okombahe area to some Damara in 1870. Later, the colonial authorities created several other reserves for the Damara people, among them Otjimbingwe and Sesfontein. During the 1960s, the apartheid government bought 223 farms from European settlers and in 1973 it proclaimed an area of 11.6 million acres (4.7 million hectares) as so-called Damaraland. Within the boundaries of this territory live only a quarter of the total Damara population. The same percentage may be found in the district of Windhoek, and the remainder is distributed throughout the north-central area.

Towards the end of the 18th century the Damara first came into contact with European travellers, who usually described them as hunter-gatherers. There is, however, ample archaeological evidence to suggest not only that some clans had been keeping small herds of stock for centuries, but many were also gardeners, growing tobacco and pumpkins.

In line with their predilection for small stock farming and cattle breeding, livestock production has become an important source of income for the Damara. Today, however, many work on farms, in the urban centres and on mines. The number of independent commercial enterprises is on the increase. Hundreds of teachers, clerics and officials form a modern intelligentsia, among them some of Namibia’s most eloquent politicians. In short, the Damara have succeeded in liberating themselves from their former dependency and have acquired a respected position among the people of Namibia.

Kaokoland

Beyond Sesfontein lies Kaokoland, a vast, empty and inhospitable area stretching west to the Skeleton Coast, east to Etosha and all the way north to the Kunene river on the Angolan border – a total of about 49,000 sq km (19,000 sq miles). Travelling overland here is a slow business (there are only about five driveable roads) and should never be attempted alone or without a plentiful supply of food and water, and a satellite navigation system. If you plan to do this trip, seek advice first.

It’s wiser to sign up for an organised 4x4 tour; you could find yourself heading northwest along the D3707 to the community campsite at Purros ! [map] (tel: 081 211 6291, www.spitzkoppereservations.com), on the tree-lined banks of the Hoarusib River. Set up to provide employment for the local Himba people as well as camping space for visitors, the campsite can also arrange escorted visits to Himba villages, and guides for game drives in an area that still supports significant numbers of elephant, giraffe and various antelope.

Ancient culture

Unlike Namibia’s other indigenous peoples, the Himba (a subset of the Herero nation) still live exactly as they have since they migrated down from Angola and settled in this remote area some 300 years ago. It’s a timeless lifestyle that requires no Western trappings or even running water – livestock (cattle and goats) constitutes wealth for this pastoral society, so the territory of each clan has to be large enough to allow them to move their herds enormous distances, following the few straggling pastures which spring up after the rains.

A herdsman overlooks the animals at dusk.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

As they roam this huge wilderness, the Himba construct rough “camps” to sleep in, from which they can also gather roots and hunt game. When they leave to find better grazing for their goats and cattle, household items get left behind, which they will use on their return. In a telling example of how their culture is now, having to adapt abruptly to the outside world after centuries of isolation, there have been several unfortunate incidents in the last few years where Himba camps have been denuded by unwitting tourists, who thought them abandoned.

Sensitivity towards the Himba way of life is an essential part of a Kaokoland journey. Always gain permission before you enter any of the semi-permanent Himba settlements, for instance, and ask first before you take photographs (expect to pay, too). Gifts of tobacco and mealiemeal (cornmeal), however, are usually appreciated.

A Himba man uses a gourd as a mixing bowl.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Purros is about halfway to Orupembe @ [map], some 208km (129 miles) from Sesfontein across the wide, flat Giribes Plains. You’ll see scattered herds of springbok as you travel, along with the odd “fairy circle” – small round patches of earth where no vegetation grows, possibly due to toxic chemicals left in the soil by long-dead Euphorbia bushes.

At Orupembe, the road turns east with a slow descent through rocky terrain and the dramatic Tonnesen and Giraffen passes. From here, it’s about 200km (120 miles) by road through the small settlement of Kaoko Otavi and a north turn onto the D3705 to Opuwo £ [map], the only real town in Kaokoland. (If you’re coming from Kamanjab, it’s some 254km or 158 miles on the C35 and C41.) A dusty, somewhat shambolic place with a real frontier atmosphere, Opuwo’s a good place to stock up on food and fuel. On the perimeter is a large Himba settlement where you can mingle with these strikingly dressed people – hair coiffed with mud into intricate styles, bodies shining with red ochre – as you shop at the supermarket.

If you’d prefer a self-drive 4x4 tour, you could try the circular four-day route heading north from Opuwo to Ruacana and back via Epupa Falls in the west – although it must be stressed that it’s vital to travel with at least two vehicles, to be completely self-sufficient and to carry fuel and water.

From Opuwo, take the C41 east to the C35 (the main road north to Ruacana), a journey of 142km (88 miles). Fill up with fuel in Ruacana $ [map]; you won’t have another chance until you get back to Opuwo. Now take the C46 west for a few kilometres before continuing on the D3700 for 55km (34 miles), a picturesque drive following the Kunene river to Swartbooisdrift, where there’s accommodation and campsites at Kunene River Lodge, renowned among birders as the place to see Cinderella waxbill. The road west from here is atrocious; better continue south on the D3702 for 20km (12 miles) to Ehomba % [map], followed by the D3702 for 10km (6 miles) then the D3701 for 31km (19 miles) to the tiny Himba settlements of Epembe ^ [map] and Otjiveze. Head northwest on the D3700 for 31km (19 miles) to Okongwati, continuing north for 73km (45 miles) to Epupa Falls & [map]. The Baynes Mountains, Kaokoland’s highest peaks, rise to the west.

Epupa is a stunning sight, comprising a series of rapids and waterfalls, the tallest dropping 37 metres (120ft), that thunder into a palm and baobab-fringed gorge surrounded by desert. At one point, the Namibian and Angolan governments held serious talks about implementing a giant hydroelectric dam project that would have submerged the entire Kunene Valley (including the waterfalls), much of the Himba’s territory, and many sacred ancestral grave and fire sites, but fortunately this idea has been shelved.

From Epupa, retrace your steps along the same route to Otjiveze and then continue south for a further 73km (45 miles) back to Opuwo.

Another option is to explore the western Kaokoveld, travelling down to Orupembe through the two long, barren but hauntingly beautiful valleys (Hartmann’s and the Marienfluss) that run north to south from the western end of the Kunene River. Trips can be organised through specialist tour operators, or by booking into the superbly isolated Serra Cafema Lodge, a fly-in tented camp on the dune-fringed banks of the Kunene.

A Himba hut.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications