The first European to step onto Namibian soil was the Portuguese explorer Diego Cão, who reached the Skeleton Coast in 1486 and put up a stone cross at Cape Cross to prove it. He was followed in 1488 by another explorer, his fellow-countryman Bartholomeu Diaz, who erected his own cross at Angra Pequena (which is now known as Lüderitz).

Detail of a pillar erected by the Portuguese explorer Diego Cão in southern Angola.

Scala Archives

Portuguese exploration of Africa

It started in 1415, when the Portuguese navy, inspired by Henry the Navigator, captured the Moroccan port of Ceuta. Though the battle lasted less than a day, the capture of Ceuta arguably unleashed a wave of European expansionism that shaped the world as we know it today. It also provided impetus to an era of Portuguese naval exploration driven by two main motives: to find a route through to the Indian Ocean and establish control over the spice and gold trade that linked East Africa, Arabia and Asia, and to locate and forge links with the legendary lost Christian Kingdom of Prester John (Ethiopia).

Portugal underestimated how far southwards Africa stretched. The Senegal River was reached in 1444, the Gambia in 1446, Sierra Leone in 1460, and São Tomé in 1474. Only in 1486, however, did Diego Cão make it as far as present-day Namibia, erecting a cross at Cape Cross shortly before he died.

Where Cão left off, Bartholomeu Diaz followed, landing at present-day Lüderitz in 1488, before he unwittingly rounded the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian Ocean. Finally, in 1499, Vasco da Gama made it all the way to India. Within another ten years, Portugal had established a permanent presence in Goa and East Africa, and while its influence over Namibia was never great, both neighbouring Angola and nearby Mozambique remained Portuguese colonies until 1975.

Prior to this, the coast of Namibia – like the rest of sub-Saharan Africa – was terra incognita to European navigators. Furthermore, unlike the Indian Ocean coastline of eastern Africa, which had entered into regular maritime trade with Arabia by the start of the second millennium AD and was visited by Indian and Chinese ships in mediaeval times, the west coast of sub-equatorial Africa probably existed in almost total isolation from the rest of the world at this time.

Only in the 15th century, as trade with the East took off, did European ships – more specifically, the Portuguese – start to search for a new sea route to India via the Cape of Good Hope, a route that took them along the coast of Namibia. But for centuries after Cão and Diaz first landed in what is now Namibia, the forbidding climate and inhospitable terrain shielded the land from European expansionism. For both explorers and traders, the very notion of settling on a coastline that offered neither food nor water for sustenance – nor slaves and ivory for trade – was a complete waste of time. As the captain of a passing Dutch vessel, the Bode, noted: “Here for nothing in the world is there even the smallest gain for our masters… there is only sand, rock, and storm.”

Drawing of Walvis Bay in the 19th century.

Getty Images

Towards the end of the 18th century, however, the ports of Lüderitz and Walvis Bay began to be visited more frequently by whalers and seal-catchers from France, Britain and America, and passing Indian trade. The areas around these harbours, meanwhile, began to be harvested for guano.

The Oorlam invasions

With war on the horizon in Europe, in 1793 the Dutch government claimed Walvis Bay (the only decent deepwater port along the coast) and Angra Pequena, as well as Halifax Island off the coast. When the British annexed the Cape Colony two years later they, too, hoisted their flag along the Namibian shore – although it was not until 1878 that they annexed Walvis Bay and its environs (approximately 1,165 sq km/450 sq miles) for themselves as well.

Namibia’s northernmost peoples – the Ovambo and the Kavango – remained relatively isolated from the troubles down south during the Oorlam invasions.

Even at this stage, however, scarcely anything was known about the Namibian interior, although the discovery of the Orange River in 1760 did open up the territory somewhat to traders and hunters as well as to missionaries.

At the turn of the 18th century, southern Namibia was thrown into a turmoil with the arrival of large numbers of Oorlam people, roving bands of dispossessed Khoisan fleeing Dutch persecution in the Cape. Although the Oorlams were of the same origins as the Nama pastoralists already settled in southern Namibia (and spoke a similar language), many had guns and horses, giving them both mobility and a technological edge. Some were outlaws, while others had broken away from scattered Nama settlements en route to take their chances with the Oorlams as they traded, thieved and hunted their way north.

Thanks to their commando-style military structures, which they’d copied from the Boer frontiersmen, the South Africans quickly subdued the indigenous Namibians and their bows and arrows. Soon the Oorlams – led by a paramount chief named Jonker Afrikaner – had subjugated the Nama and Damara in the south and reduced the Herero clans in the east and centre-north to mere vassal status.

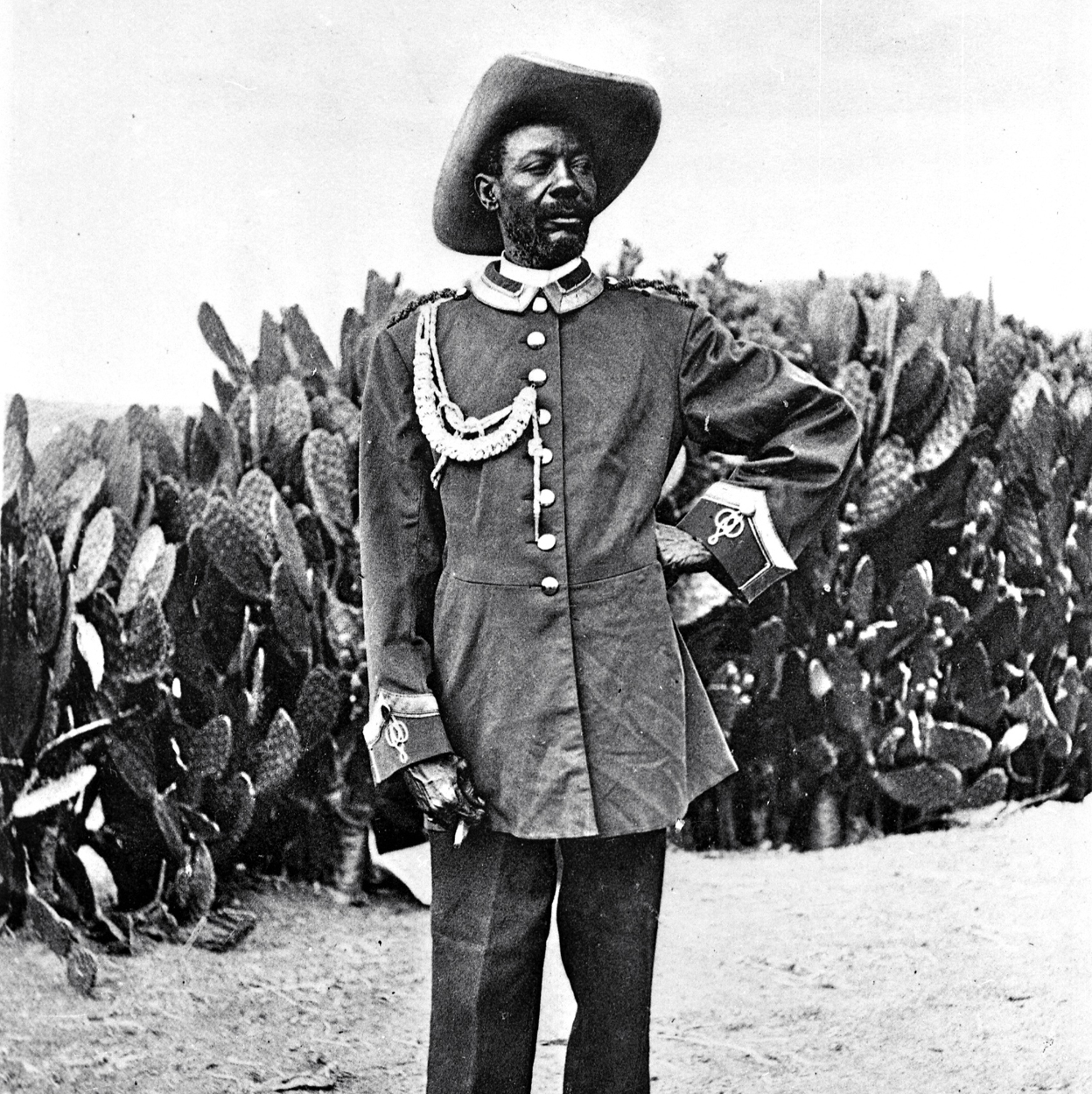

The mighty Herero chief, Maherero.

Public domain

Nevertheless, the locals fought back. Ongoing skirmishes amounting almost to low-level warfare raged throughout the region for the next 70 years, as Oorlam commandos continued to raid the cattle of local clans and pillage settlements. The inexhaustible demand for commodities to trade for arms also led to the wholesale slaughter of game stocks, especially elephant and ostriches.

Traders and missionaries

Temporary calm was brought to this unhappy situation in 1840, when Jonker Afrikaner struck a peace deal with Paramount Chief Oaseb of the Nama. Southern Namibia was effectively split between the Nama and a range of Oorlam groups, while the Oorlams obtained the rights to the land between the Swakop and the Kuiseb rivers in the centre of the country. Jonker Afrikaner was also given rights over the people living north of the Kuiseb. In practice, this meant that the Oorlams formed a buffer zone between the Nama in the south, and the Herero further north in Kaokoland – although the latter had been steadily moving south themselves ever since the middle of the 18th century.

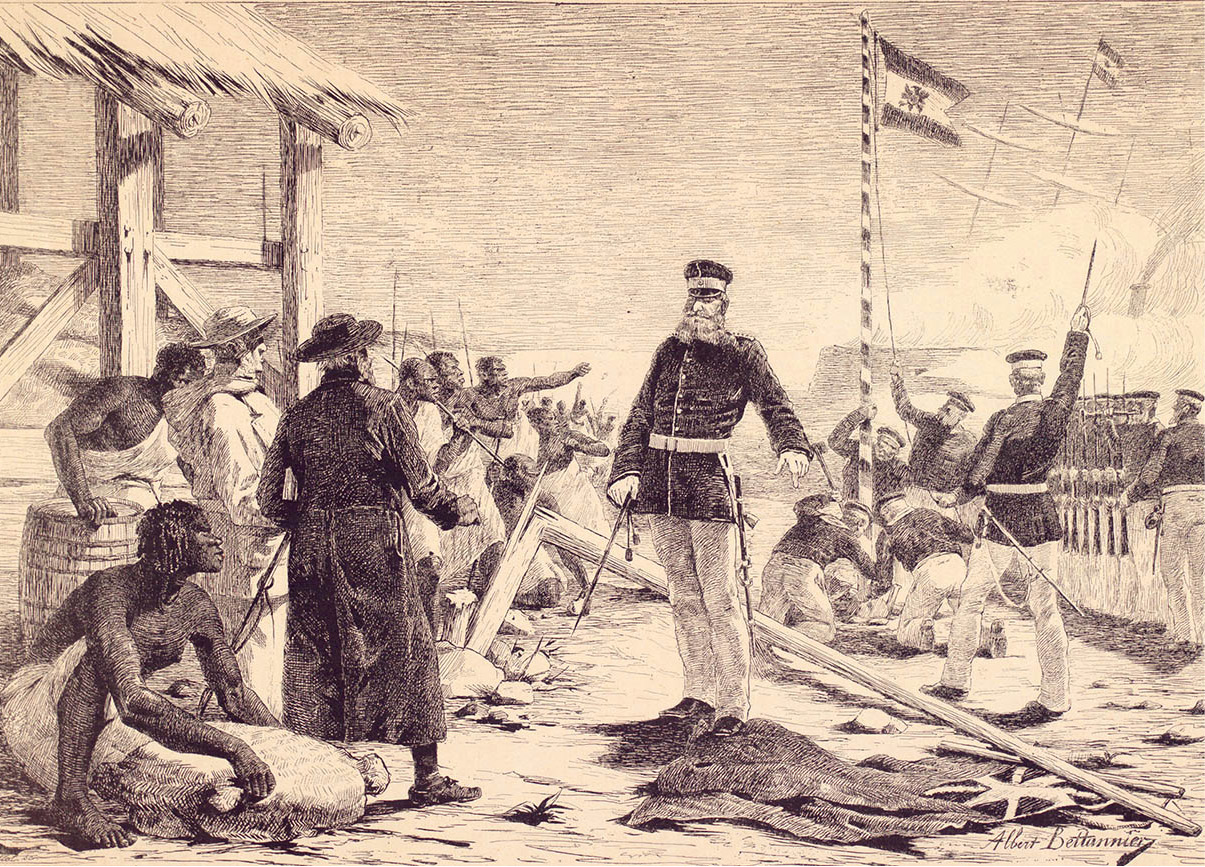

Drawing by Albert Bettanier.

akg-images

Nonetheless, the disruption of indigenous community life continued, thanks to the reduction of cattle stock through warfare and drought and the destruction of water reserves. The resulting discontent deepened opposition to Jonker Afrikaner’s rule, and forged a broad alliance between Herero, rival Nama clans, traders and missionaries. Yet Afrikaner’s central Namibian “empire” continued even after his death in 1861, when his eldest son and heir, Christian, inherited the reins of power.

By this time, traders and hunters on the lookout for valuable commodities such as ostrich feathers and ivory had begun venturing deep into the Namibian interior. One of the most important figures was a certain Charles John Andersson, who – with the help of a band of hunters acting as a sort of armed guard in this lawless territory – established a trading post at Otjimbingwe and started to explore new trade routes further north and east. It was his men who in 1863 shot and killed Christian Afrikaner, who had rashly mounted a raid on Otjimbingwe.

In the traders’ wake came various missionaries – in particular the London Mission Society, Wesleyan Methodists, and Rhenish and Finnish Lutherans – who established small stations throughout the south and central regions. They were able to extend their influence reasonably easily during the 1870s, a relatively calm decade thanks to a treaty signed in 1870 by the Herero chief, Kamherero and Christian’s successor, Jan Jonker Afrikaner. But by the 1880s fighting had once again broken out between the various Nama groups, the Herero and the Basters – new arrivals from the Cape who had settled in the Reheboth area. All these groups had by now also started to trade extensively with the Europeans.

It was into this cauldron – pre-colonised by European technology and awesome firepower, as well as the spread of Christianity – that Germany now stepped.