THE FIFTIES

When I arrived at 20th Century Fox in 1949, the first thing I did was crawl all over the lot. I was fascinated by how everything was done—how the various shots were edited into what seemed to be a seamless whole; how old costumes from the wardrobe department were revamped to look brand new; how the lighting made rickety flats look like real rooms.

Like every movie studio, Fox was just awash in physically beautiful women. You would encounter gorgeous every ten feet. It was not an environment for an ascetic personality. I was nineteen when I began there, so it goes without saying that I had great times on and off the lot. No apologies, no regrets.

One of my publicity dates was with a young Rita Moreno. I say “publicity date” because it was set up by the studio publicity department, and, while Rita was stunning, she was also very involved with Marlon Brando at that time and for a long time afterward. I liked Rita, but I liked Marlon, too, and wasn’t about to poach on his territory. She knew it, and I knew it, but we went out a couple of times, closely accompanied by photographers. It was the way the game was played, because the studio set the rules.

I started out in shallow water—I made tests. I tested opposite almost every actress that Fox was thinking of signing. I tested opposite superb actresses, I tested opposite women who were the mistresses of powerful executives at the studio, I tested opposite women who should have used quotation marks when they listed their occupation as actress.

And I tested opposite Marilyn Monroe.

Marilyn. Everyone always wants to know about Marilyn.

I have no horror stories to tell. I thought she was a terrific woman and I liked her very much. When I knew her, she was a warm, fun girl. She was obviously nervous about the test we did together, but so was I. In any case, her nervousness didn’t disable her in any way; she performed in a thoroughly professional manner. She behaved the same way in Let’s Make It Legal, the film we later made—nervous, but eager and up to the task.

Obviously, she was extremely attractive, and she already had that special quality of luscious softness about her. She was completely nonthreatening, unless you were another woman trying to hold onto your man.

Everyone knew that she was the girlfriend of Johnny Hyde, a powerful agent at William Morris. Whenever I saw them together, Johnny gave every indication of being attentive and loving, so I’m inclined to believe that the relationship was a very positive thing for Marilyn. For Johnny, maybe not. For one thing, he was married; for another, he died young, of a heart attack in 1950.

Certainly, it was positive professionally; Johnny got Marilyn the part in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle that made everybody sit up and take notice. Given Johnny’s presence in her life, I made sure that my attraction to Marilyn came across as nothing more than professional admiration.

After we made Let’s Make It Legal, Marilyn went her way, and I went mine. She became the biggest star on the Fox lot, and, along with Elizabeth Taylor, the biggest female star on the planet.

Years later, Marilyn began dropping by the house where Natalie and I lived. Our connection was through Pat Newcomb, her publicist. I had known Pat since our childhood. She had also worked for me and often accompanied Marilyn to our house. I bought a car from Marilyn—a black Cadillac with black leather interior.

Marilyn was relaxed and enjoyed herself with us, except for one time when Conroy, a black Lab that Bing Crosby gave me, growled at her. To this day I don’t know what happened. Conroy was a happy dog, but there was something about Marilyn he didn’t like. They say dogs know when an earthquake is coming. Maybe Conroy sensed something profoundly off-center about her.

I never saw the Marilyn of the nightmare anecdotes—the terribly insecure woman who needed pills and champagne to anesthetize her from life, and who reached a place where she couldn’t get out more than a couple of consecutive sentences in front of a camera.

When I would talk with other actors, such as Tony Curtis, about their experience of acting with Marilyn, they described it as being like working with a small child or an animal. If the animal manages to do its part right, that’s the take they’re going to use, whether you are any good or not, which is why actors hate to work with them. In Some Like It Hot, Tony and Jack Lemmon had to nail every take, because Billy Wilder had no choice but to use the takes in which Marilyn was good, or even adequate—there was no guarantee she would be able to do a scene more than once.

Clearly, Marilyn had tremendous problems, and they got worse as she got older. She was prone to depression and was terribly anxious about her level of competence—another actress who was frightened of her own profession. The result was that she projected her insecurity onto everyone who was working with her. Her co-workers lived their lives in a state of terrible nervous tension—Was she going to show up? And if she did, would she be able to get anything done?

The audience doesn’t care about that kind of thing—all they have to go by are the finished films, and Marilyn was generally excellent in them. But the people who made the movies were all too aware of how difficult it had been to get the movies made, and how much over budget they went because of her. At times, when you talked to people in the industry about Marilyn, you’d sense the same sort of hostility that the guys at Paramount expressed on the subject of Betty Hutton.

One thing about Marilyn: She needed to be a star, not out of garden-variety professional ambition, but as a means of validating herself, of proving that her father had made a terrible mistake when he abandoned her mother and her. Making it was the only way she had of proving that everybody who had refused to take her seriously, who had taken advantage of her when she was a young actress around town, was wrong. Yet the bigger she got, the more her insecurities increased. The more her insecurities increased, the harder it became for her to deal with the stardom she wanted so badly. A vicious circle.

Marilyn had an innately luminous quality that she was quite conscious of—she could turn it on or off at will. The problem was that she didn’t really believe that it was enough. My second wife, Marion, knew her quite well; she and Marilyn had modeled together for several years, and were signed by Fox at the same time, where they were known as “The Two M’s.” Marion told stories about how the leading cover girls of that time would show up to audition for modeling jobs. If Marilyn came in to audition, they would all look at each other and shrug. Marilyn was going to get the job, and they all knew it. She had that much connection to the camera.

I got the feeling that because Marilyn hadn’t had any family to speak of when she was growing up, she always gravitated toward empathy or strength, or supposed strength, which was the basis for most of her relationships. Pat Newcomb was completely dedicated to her; it was a bond that was more familial than professional.

Men with whom she became romantically involved—Elia Kazan, Arthur Miller, Frank Sinatra, even Joe DiMaggio—were all assertive by nature and seemed to have all the answers; people on whom she became emotionally dependent, such as Paula and Lee Strasberg, were even more so. I don’t think there’s any question that Marilyn was deeply disturbed at the end of her life. Part of the reason they pay you in show business is to be there on time, and Marilyn could no longer do that. Schedules and budgets were kindling for her wavering temperament.

When Marilyn died, Pat Newcomb was utterly devastated; Marilyn had been like a sister to her, a very close sister, and she took her death as a personal failure. Marilyn’s death has to be considered one of show business’s great tragedies. That sweet, nervous girl I knew when we were both starting out became a legend who has transcended the passing of time, transcended her own premature death.

I wonder if her immortality would give her any sense of satisfaction. Somehow I doubt it.

• • •

Marilyn’s story is evenly split between her years of stardom, when the whole world knew who she was and cared passionately, and the years before, when nobody was aware of her and nobody cared. Just before Marilyn met Johnny Hyde and her life changed for the better, just before we tested and made a movie together, Marilyn was living at the Hollywood Studio Club, one of the more fascinating places in Hollywood history.

It was nothing more or less than a chaperoned dormitory for young girls, and was in operation from 1916 to 1975.

The Studio Club came about in this way: Before World War I, the movies hit in a big way, and thousands of young people of both sexes began flooding Hollywood each and every year. If they had saved some money, they could get cheap space at one of the dozens of garden court apartment complexes that dotted southern California.

And if they didn’t have any money, they could double up, or triple up. And if they really didn’t have any money, girls could stay at the Studio Club, which was built by private subscription. In the early days, actresses such as Mae Busch, ZaSu Pitts, and Janet Gaynor were all boarders. Actually, a lot of its residents became more famous as wives than as actresses. Dorris Bowdon, who played Rosasharn in The Grapes of Wrath, later married Nunnally Johnson, who wrote the script for the film, and had a long and happy life with that excellent writer.

The idea for the club began when a group of ambitious young women began having meetings at the Hollywood Public Library to read plays and discuss strategies for getting into the movies. One of the librarians began to get concerned about the safety of girls who had to live in cheap hotels, and began soliciting funds to rent an old house for them on Carlos Avenue. Constance DeMille, the wife of Cecil B., was crucial in the financial foundation of the club, as was Mary Pickford.

In the early 1920s, many of the studios and a lot of businessmen donated money for the construction of a permanent building specifically to house the Studio Club. Their generosity was stimulated partly by altruism, but also by alarm. The three huge scandals of the early 1920s—Fatty Arbuckle’s manslaughter trial, the William Desmond Taylor murder, and Wallace Reid’s death from the effects of drug addiction—scared the entire industry. In order to forestall censorship, they needed to emphasize propriety whenever possible, and the Studio Club was a perfect vehicle to embody the God-fearing nature of Hollywood. Famous Players-Lasky—the forerunner of Paramount—donated $10,000, and MGM and Universal $5,000 each. Norma Talmadge kicked in $5,000.

The project cost $250,000 and opened in 1926 at 1215 Lodi Place, just south of Sunset Boulevard, in the heart of Hollywood. It was a three-story Mediterranean building designed by Julia Morgan, who designed San Simeon for William Randolph Hearst. Each room at the club had a nameplate identifying the people who had contributed at least a thousand dollars to the building fund. There were rooms named for Douglas Fairbanks, Howard Hughes, Gloria Swanson, and Harold Lloyd, among others.

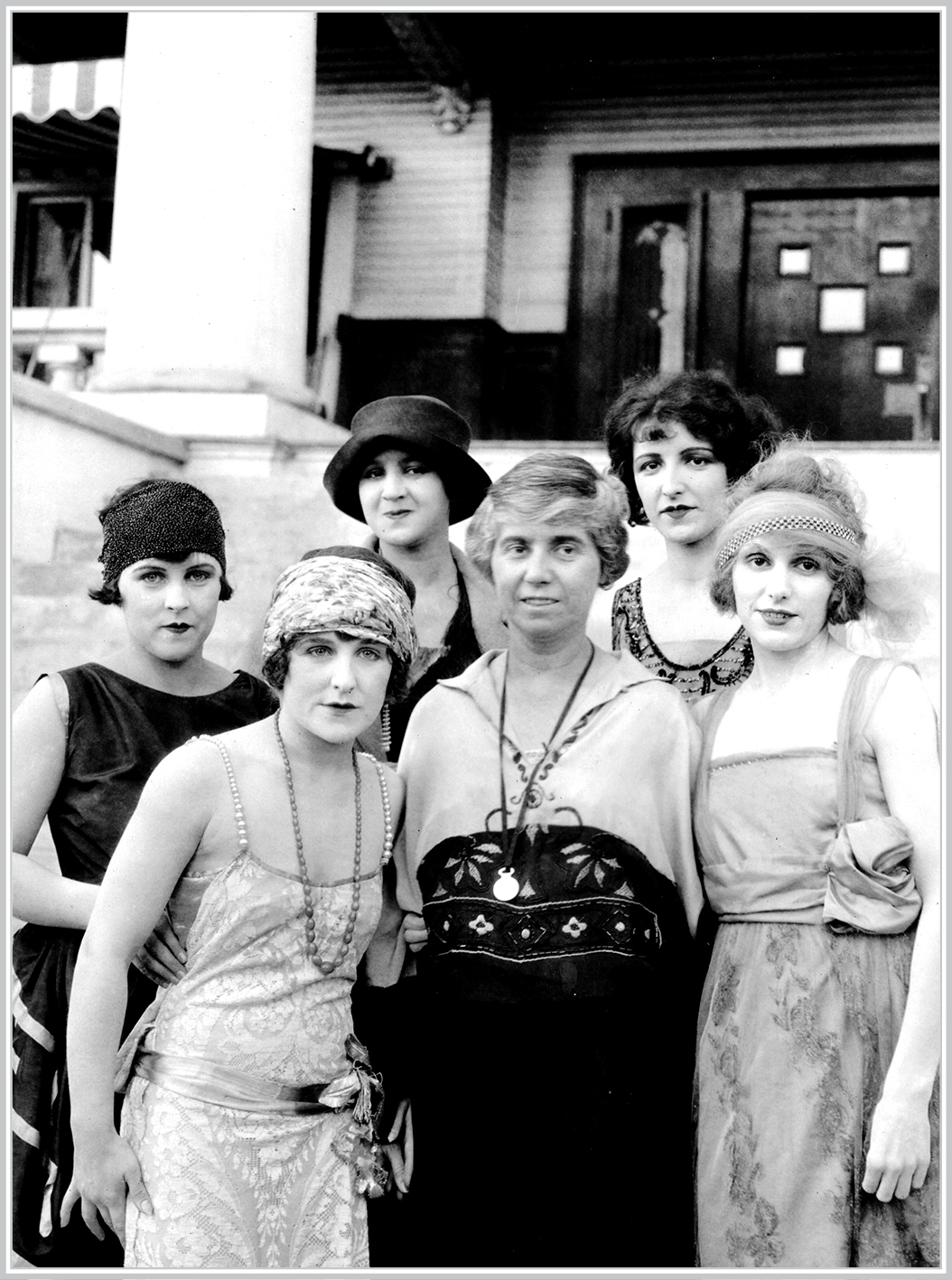

Marjorie Williams (center), director of the Hollywood Studio Club, stands with the girls at Carlos Avenue clubhouse

The club could house eighty women, who initially paid ten dollars a week for a room shared with two others, or fifteen dollars a week for a room with one other woman. There were modest age requirements; you couldn’t be younger than eighteen or older than thirty. One of the few times they waived the age requirements was for Linda Darnell, who was only sixteen when she arrived. The club offered classes and also offered plays and fashion shows. The longest a girl could stay was three years. It wasn’t a bad place to live at all; the girls had a way of bonding with each other, and the club made no effort to impart a religious message to the residents. Alcohol was a no-no, but smoking was permitted. It goes without saying that men were not allowed in the rooms; when a girl had a date, the guy would wait downstairs until the girl came down a luxurious staircase that led from the lobby to the dorm rooms. By the 1930s, the building’s yearly budget ran to around $50,000, and most of that was covered by the girls’ rents; any deficit was made up by the national YWCA.

Marilyn lived there for a little more than a year, from 1948 to 1949, in rooms 307 and 334. She told me her rent was fifty dollars a month, which included two meals a day—a great deal for a girl struggling to make ends meet. She liked to reminisce that the reason she posed for the famous nude photographs was to get enough money to pay her rent at the club. (People at the club, however, would insist that she had left there by the time of that photo session.)

The girls who resided at the club could tell who among them was likely to make it. There was a certain inner resolution, a confidence, possessed by those who were heading for bigger things. I was told that when Marilyn lived there she was quiet—I believe it—and was usually carrying a book. When she came down for breakfast, the other girls would notice and be impressed, but not jealous. There was always something vulnerable and likeable about her.

During the Depression, when I was just starting to watch movies, jobs were scarce, and times were tough. If you were an average girl trying to break into the movies, and were unable to get space at the Studio Club, you might be rooming with five or six other girls in a bungalow apartment. Two girls would share a bed, one would take the couch, one would be on a reclining chair, and whoever drew the short straw would be on the floor with a pillow. The girl who had worked most recently would pay for groceries, and someone was designated to stay close to home to answer the phone, just in case a job came through for any of the housemates. None of the girls had a car—you either took the streetcar, or counted on your boyfriend, if you had one, to take you where you needed to go. Even under these conditions, you could count on a couple of the girls not being able to make their share of the rent.

Diana Serra Cary is a fine writer who did time as a child star in silent movies as Baby Peggy. She wrote about the bizarre circumstances of Hollywood in those years: “There were two Hollywoods, the packaged export on which our very lives depended and the real thing, on which most of us practically starved to death . . . Among a dozen of our close friends, not one family could stay on top of the electric, gas, water and telephone bills as well. One or the other was always being shut off or ‘temporarily disconnected.’ This brought into existence an unspoken code of conduct that helped us cope with an abnormal situation which, for the time being at least, was our way of life.

“If we were the ones whose telephone was working (but whose water had been turned off) . . . we let the next-door neighbor, who was without phone service, call . . . and she in turn gave us enough water to make supper. If our gas was off it was no disgrace to put the makings of dinner in a roaster and march upstairs to Mrs. Lundquist’s kitchen. There we cooked the meal while Mrs. Lundquist was downstairs using our phone. The combinations and reciprocations were endless, and fortunately everyone possessed a sense of the ridiculous, which made it possible to laugh instead of cry over the way things were.”

By these standards, which were more or less normal for all those who didn’t have a contract at a major studio during the 1930s, the Hollywood Studio Club was nirvana. The club would even carry you until you could make good on your back rent.

There’s a semifamous movie called Stage Door that owed a great deal to the Studio Club. The basis for the 1937 movie was a play by George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber about a theatrical boardinghouse in New York called the Footlights Club, a women-only establishment like the Studio Club. Kaufman and Ferber were high-end writers, and the movie’s cast included Katharine Hepburn, Ginger Rogers, and Lucille Ball, but Gregory La Cava, the director, thought the script needed some salt and pepper.

La Cava sent his mistress, an actress named Doris Nolan, over to the Studio Club to hang out and listen to the women talk. “Find me some dialogue that’s alive,” he instructed her. “Get some case histories. Who are these kids? Why do they want to be in pictures? Where do they come from? What was their home like? Small town? Why did they leave home to come here? Are they having any success? Have they been to the casting couch? Was it worth it? I want it in their own language.”

Stage Door was a big hit, and its success inspired Warner Bros. to announce production of a movie starring Olivia de Havilland and Anita Louise that would actually be set at the Hollywood Studio Club. Unfortunately, the movie never happened.

Others who lived there at one time or another included Barbara Hale, Donna Reed, Frances Bergen (wife of Edgar, mother of Candice), Kim Novak, Maureen O’Sullivan, Sharon Tate, Dorothy Malone, Gale Storm, Marie Windsor, Linda Darnell, Rita Moreno, Barbara Eden, Evelyn Keyes, Sally Struthers, and Ayn Rand. (Most of the inhabitants were aspiring actresses, but not all; if you wanted to work in the movies, as a writer or editor or designer or even as a secretary, you could get into the club.)

All the girls had money problems, or they wouldn’t have lived there, but evidently Ayn Rand was unusually broke even by the standards of the club. One philanthropist gave fifty dollars to be earmarked for the poorest of the girls. The director of the club chose Rand, who thanked the club for the money and promptly used it to buy black lingerie. Rand, of course, wanted to be a writer, and she had gotten a role in Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings as an extra. It was on that film that she met the man she would marry, and the story goes that she wrote Night of January 16th while living at the Studio Club.

Evelyn Keyes was a young woman who had been raised in Georgia and had an accent to match. That accent would eventually work to her advantage when she was cast as one of Scarlett O’Hara’s sisters in Gone with the Wind. Several years before that, her marriage had broken up, and she went to the Studio Club because she had no place else to stay.

She thought she had died and gone to heaven. She appreciated the club because it was respectable—it was one of the few spots in Hollywood she thought her mother would approve of. “It was a place where you were protected and it was reasonable,” she said. “They weren’t trying to make money. They were trying to make a haven for young girls.”

Marie Windsor told me that it was a great place to live because all the boarders there were at the same stage of their lives—the beginning, before they’d had many disappointments or failures, and the world was still opening up before them. Marie said that Marilyn Monroe moved out the same week she moved in. She didn’t know her then, but got to know her a little later, about the time Marilyn was making The Asphalt Jungle. She liked her, but she said that one of the executives had to tell Marilyn to come to work in clean clothes. (I guess MGM had higher standards than the Studio Club.)

Marie got a job as a cigarette girl at the Mocambo from a want ad that went up on the bulletin board at the club. The Mocambo was where she met the producer Arthur Hornblow, who liked her and got her work with the choreographer Leroy Prinz. After that, Marie was off to the races, and a nice career that included working for Stanley Kubrick on The Killing. That was the way careers began in the Hollywood of that time. Coincidence, luck, timing, eagerness—pretty much the same way careers have always begun.

Kim Novak was remembered as being very neat and clean—nobody could look more glamorous in a man’s white shirt and Levi’s. Kim never liked Hollywood, or, for that matter, the movies; she didn’t want to leave the cozy confines of the club, which had by then raised the maximum length of stay to five years. After she left, she donated money and clothes to the club.

I know that my friend Jeffrey Hunter courted Barbara Rush when she was living at the club; in fact, the club gave a party when they were engaged. And there were various legends that may or may not have been true. I once heard a story that a hotel clerk registered at the Biltmore as a cousin of King Alfonso of Spain. Hollywood has always been impressed by titles, but she couldn’t pay her bill. Somehow or another, the wife of the actor Antonio Moreno took her in and placed her at the Studio Club, where nobody was aware of her fraud.

When I was a young man around Hollywood, stories about life at the club were legion, though almost all of them would be rated PG-13 at worst. For the most part, its reputation was quite good, but there was the occasional embarrassment; one of the girls was murdered in front of the club by her boyfriend, who then proceeded to kill himself. Evelyn Keyes remembered that pregnancies were not exactly uncommon among the residents. During its final decade, the club was home to people like Sharon Tate, Nancy Kwan, Susan Saint James, and Sally Struthers.

Eventually it was overtaken by changing times. The idea of a chaperoned dormitory became gradually passé; many girls opted for the simpler alternative of shacking up with their boyfriends. The charter of the club expanded the eligibility requirements to include dancers and models, but it began losing lots of money; in 1971 it stopped serving meals and began to function as a regular hotel in addition to taking care of the girls.

The Studio Club finally closed in 1975, and the building was awarded landmark status in 1979. Today it is still the property of the Los Angeles YWCA.

In the fifty-nine-year history of the building on Lodi Place, some ten thousand women lived there.

Ayn Rand always retained a soft spot for the club, and wrote about it: “The Studio Club is the only organization I know of personally that carries on, quietly and modestly, this great work which is needed so badly—help for young talent. It not only provides human, decent living accommodations which a poor beginner could not afford anywhere else, but it provides that other great necessity of life: understanding. It makes a beginner feel that he is not, after all, an intruder, with all the world laughing at him and rejecting him at every step, but that there are people who consider it worthwhile to dedicate their work to helping and encouraging him.”

Notice Rand’s use of the masculine pronoun. Interesting. As was the Studio Club, a place that could only have existed as part of the movie business, and only in Hollywood.

• • •

People sometimes ask me if I can identify any defining characteristic common to the women I’ve worked with over a nearly seventy-year career. The truth is that the vast majority of those who came up during the studio system were well defined in their own minds. They knew what they wanted, and if they didn’t, they didn’t last long. Almost all of them had endured hardships as kids, and as show business invariably presented its own kinds of hardships, they were by nature and necessity survivors.

All of them were aware that they had a limited period of opportunity within which to achieve and consolidate stardom; most of them were likewise aware that stardom is a finite state and that eventually that state would pass. At that point, the pressure would be off, so for most of them working could be more of a pleasure at sixty or seventy than it had been at thirty. I also picked up a certain sense of guilt—a number of them felt that they had shortchanged their families and their children in the pursuit of professional success.

Hearing that made me respect people like Claudette Colbert and Kate Hepburn all the more, because they had the self-awareness to forgo having children. That may be a partial reason why they had the successful careers they did—their eyes were fixed firmly on the prize, and they weren’t hampered by competing emotional or psychological demands.

Most of these women centered their lives around their acting, but not everybody shared that consuming passion. Doris Day worked hard for a lot of years, and moreover she was a triple threat—she could sing, she was a successful comedienne, and she was excellent in serious roles. But it gradually got to the point where she didn’t want to be in the business anymore, and she walked away when she was only fifty or so, something very few performers do. The ones who leave, who have the fortitude and the lack of ego to do something else with their lives, are particularly interesting to me.

Doris was a band singer during World War II and got into musicals at Warner Bros., where she made a big splash because of her sunny smile and creamy singing voice.

She projected midwestern pluck and optimism, and a kind of scrubbed quality in spite of a private life that didn’t always conform to her public image. She didn’t get a lot of love from the critics, who treated her as an offshoot of June Allyson, and who tend to disparage anyone who has enormous commercial success.

Let me tell you something: Doris could do anything asked of her, do it well, and make it look easy. She could do light comedy with Cary Grant; she could do drama with Jim Cagney; she could do thrillers for Hitchcock.

She certainly had need of inner reserves of optimism because her husband, Marty Melcher, was a crook and left her nearly broke, then conveniently died, leaving Doris holding an empty bag.

Doris did what one of her screen characters would have done: she rolled up her sleeves and got to work replenishing her bank account. And when the job was done, she decided to do what would make her happier than show business: working with animals and enjoying her life. She declined every movie offer, even the good ones, and she even resisted appearances on the Academy Awards—she just wasn’t interested in keeping her hand in anymore.

It’s not a viewpoint I share—I have a passion for show business, always have and always will—but it’s a viewpoint I respect. Doris was a performer who endured for a very long time. She always gave great value for the money; she earned my respect and that of the audience.

• • •

Susan Hayward was a Brooklyn girl, the daughter of a transit worker. She was also a movie star. She worked hard, she treated people well, and she had a great reputation around the Fox lot. Among the people she treated kindly was one Robert Wagner.

The name of the movie we appeared in together was With a Song in My Heart, in which Susan played Jane Froman, a popular singer who made a comeback after almost getting killed in a plane crash. I played a young soldier existing in a catatonic state who was lured back to life by Jane Froman’s singing to me.

It sounds corny. It was corny, but it also happened to be a true story, and Susan played it for all it was worth, as did I. Shooting that short scene took about three days, and Susan was so deeply into the emotions of the moment that she was brought to tears over and over again. She worked very hard to give me everything I needed to play the scene, and her sincerity and passion compensated for my inexperience.

The picture was directed by Walter Lang, who became a good friend, and edited by Watson Webb, ditto. It was a phenomenal break for a young actor, and suddenly, I had a career. Susan got an Oscar nomination for the film, one of five she would earn.

By the time we worked together, Susan was a name-above-the-title star, with a rapidly growing list of hit pictures, but she never had it easy. She’d tested for the part of Scarlett O’Hara in 1939, but it was too soon for her; she didn’t have Vivien Leigh’s rapturous beauty or, at that point, her skill set.

Susan was one of those stars who put the pieces together slowly, film by film, year by year. Her first big picture was DeMille’s Reap the Wild Wind, with John Wayne and Paulette Goddard. She worked again with the Duke in The Fighting Seabees, back at his home base of Republic, which only indicates Paramount’s lack of faith in her—they would never have lent out anybody they valued to Republic.

She worked steadily throughout the 1940s, and for a time she was at Walter Wanger’s operation, which undoubtedly meant that she was either being chased around Wanger’s desk or allowing herself to be caught. Long before Wanger shot Jennings Lang in the balls for moving in on his wife, Joan Bennett, he was well known for preying on actresses.

The 1950s were Susan’s prime. She won an Oscar for I Want to Live!, and she was in big pictures like The Snows of Kilimanjaro, David and Bathsheba, I’ll Cry Tomorrow, and a very good Robert Mitchum picture about rodeo cowboys called The Lusty Men. She made several good movies with Ty Power, and became part of his social group; Cesar Romero thought the world of her.

Susan was a physically small woman, who became close to the astrologer Carroll Righter and paid close attention to his forecasts. Her on-screen style was sexy, direct, and tough when she needed it to be. She was very much in the mold of actresses like Stanwyck and Davis, but her strong on-screen sense of self didn’t carry over into her private life. Her first husband, Jess Barker, was a small-part actor who had a habit of slapping her around; they had a particularly nasty divorce involving the custody of their twin sons, and the word around the lot had it that Susan was so distraught over the situation that she attempted suicide.

Afterward, she was as big a star as ever, until her career slowed down in the 1960s. Susan stepped away for a while to concentrate on her second marriage, which was quite successful. She was set to go into television when she became ill with a brain tumor.

Susan had agreed to present the Best Actress award at the 1974 Academy Awards, but she was in failing health. My friend, the great makeup man Frank Westmore, sailed into battle and helped her out. He custom made a wig for Susan so that she could still sport her trademark red hair, and did her makeup so impeccably you never would have known she was undergoing radiation treatments. With Frank’s help, Susan’s last public appearance was a triumph.

She died in 1975, when she was only fifty-seven years old. Her grace, patience, and generosity with an inexperienced newcomer changed my life. I will always be in her debt.

• • •

One of the most breathtaking women I’ve ever seen was Jean Peters, who was at 20th Century Fox in the early and mid-1950s. I was besotted by the woman.

Susan Hayward

Jean was from Ohio—Canton, to be specific—and she was the Midwest at its best: a sincere, loving personality, to which she added stunning looks. She originally came to Hollywood as a prize for winning the Miss Ohio State pageant, and somehow or other landed the job as Tyrone Power’s leading lady in Captain from Castile within a year of arriving in town. She didn’t have much to do in the movie, although she did it well.

Darryl Zanuck worked hard to make her a star, using her in all sorts of movies: comedies (It Happens Every Spring), Oscar bait (Viva Zapata!), and throbbing melodramas (Niagara).

Jean was good in everything, but she was never great. Something was lost in the space between her gorgeous face and the film running through the camera. She was beautiful on-screen, but in a slightly antiseptic way; the sensuality she had in person didn’t register on celluloid, and as an actress she seemed placid, without a lot of fire.

Darryl saw the problem and attempted to elevate Jean’s temperature by casting her as a tempestuous pirate queen, the sort of part that would normally be played by Maureen O’Hara, but that strategy wasn’t successful, either. She worked in a couple of big hits like Three Coins in the Fountain and with Spencer Tracy and me in Broken Lance, but she ended up quitting the movie business in 1955 at the age of twenty-eight. It was all very strange; it may be that Jean was simply too inhibited for a movie career—she couldn’t seem to open up in front of the camera.

But in 1957, Jean married Howard Hughes, who was never thought of as marriage material. He had had half of the women in Hollywood and could probably have had most of the other ones, as well. This was in spite of some of Hughes’s personal issues. I had a brief relationship with Anita Ekberg, who had a brief relationship with Hughes, and she told me that Hughes had a problem with premature ejaculation. This meant that a lot of Hughes’s relationships were probably due more to his bank account than to any of his other assets.

His marriage to Jean was hopelessly compromised as he declined into his various manias, and they spent most of their time as a couple separately. They were finally divorced, and Jean married Stan Hough, a second-generation producer who was the son of Lefty Hough, a wonderful old prop man and production manager at Fox. Stan was a good guy, and after they married Jean did some acting on TV for old times’ sake.

Some of the girls around Fox were on their own, but some of them were chaperoned—very much so. Debra Paget was guarded by her mother as if she were the Crown Jewels; she wouldn’t let Debra out of her sight, going so far as following her into the bathroom! This was terribly frustrating for me, because I had a major crush on Debra.

She was born in Denver, and had two sisters, who were also quite lovely, although not up to Debra’s level. Eventually she went with Howard Hughes for a while (before he landed Jean Peters), a match I’ve always suspected took place only because Debra’s mother was gobsmacked by Hughes’s money.

Debra had an interesting marital history. She married her first husband in 1958, but that was annulled in a couple of months. Her next husband was the director Budd Boetticher, and they separated after only twenty-two days. Finally, she wed a Chinese-American oilman who happened to be the nephew of Madame Chiang Kai-Shek. That union lasted seven years.

Debra came to a measure of fame in the early 1950s, when she was still a teenager. She played Jimmy Stewart’s doomed Indian love interest in Broken Arrow, and Louis Jourdan’s doomed Tahitian love interest in Bird of Paradise. I made two movies with her: Stars and Stripes Forever and White Feather, where she again played an American Indian, although this time she managed to stay alive.

She gave Cecil B. DeMille fits on The Ten Commandments, because he found her inexpressive. But what he and the rest of Hollywood didn’t know was that Debra was actually a dancer, not an actress. To dance with her was a beautiful and very sensual experience.

In 1960, she went to Germany to make two movies for Fritz Lang. In this country, the two films were combined into one and called Journey to the Lost City. Debra does a dance in the film that’s reason enough to watch it—it’s right up there with Rita Hayworth’s “Put the Blame on Mame” number in Gilda.

Debra was like Rita Hayworth in that dancing released something in her that acting didn’t—when she acted she was sincere and even soulful, but when she danced she was alive. If Darryl Zanuck had put Debra in musicals instead of casting her as a conventional ingénue, she might have had a major career. As it was, she stopped acting in 1962, when she was only twenty-nine years old.

• • •

Most of the women I knew in that era had successful careers and somewhat compromised offscreen lives, some of which involved a great deal of pain.

For some years, I hung around with Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis. Janet was brought to the movies by Norma Shearer—small world, isn’t it?—who had seen Janet’s picture on her father’s desk at a Sun Valley ski resort. Before you could say “seven-year contract,” Janet had a deal at MGM.

When I met Janet, she had been dating Arthur Loew Jr., but he couldn’t compete with Tony. Tony had energy and charm to burn, and Janet was bewitched. Janet was very much in love with Tony, but Tony . . . let’s put it this way: I liked Tony a great deal. He was a guy’s guy, but Tony’s main object of affection was always going to be Tony. He simply had to have women adore him. Whether he was on location or at the studio, he couldn’t be faithful.

Janet had not been brought up to countenance that; however much she liked the lifestyle she and Tony shared, she could not put up with infidelity indefinitely. So the marriage broke up, and Tony spent the rest of his life pollinating all the flowers he could find. Personally, I thought he was crazy to forfeit a girl with Janet’s level of beauty and class, but that was Tony.

Janet was a star, but she was also a sensible woman. She took advantage of what she’d learned at MGM when she was young, and could separate the wheat from the chaff. I remember her talking about Howard Strickling, who was the director of publicity there, and his explanation of how one person could control a crowd of dozens, if not hundreds, at a promotional appearance.

Janet Leigh

“If you stay calm,” Strickling told her, “the crowd stays calm. If you act like you’re going to stay there until the last autograph hunter is satisfied, they’ll wait their turn.” But, Strickling went on to explain, the trick is to keep moving at all times, slowly but methodically. Smile and sign, but don’t stop moving toward the car. If you stop and they corner you, it’s a much harder situation to handle. Janet said that Strickling’s crowd psychology had always worked for her, and I might add that it’s always worked for me, too.

Janet was very perceptive—and often funny—about directors. For instance, when she made Psycho, she realized that Hitchcock was far more interested in his shots than he was in his actors, and he would only concern himself with matters of character if an actor went off the rails. By the same token, he trusted his cast to summon whatever motivations they needed to explain the behavior that was indicated in the script. He would listen if an actor went to him for help, but he didn’t have limitless reserves of patience for such guidance. His attitude was: “You are an actor. You have been hired to act. I make very few casting errors, so can we get on with our business without a lot of discussion?”

Janet realized that her character, Marion Crane, had absolutely no backstory, nothing to explain why her character was having a tawdry lunch-hour affair, so she did what Hitchcock didn’t find necessary to do—she constructed an entire life for Marion before the film opens. It didn’t show on-screen, but it gave Janet a feeling of conviction about her actions, which in turn convinced the audience. And, not coincidentally, made the audience that much more shocked when she was slaughtered in the shower so early in the film.

Later in life Janet had a very happy marriage to Robert Brandt, and was thrilled when the acting career of her daughter Jamie Lee took off, and she was also very proud of her daughter Kelly. Janet was a remarkably well-adjusted woman—a class act all the way.

• • •

I didn’t really know what to expect when I worked with Joanne Woodward in A Kiss Before Dying. Joanne was a Method actress, and I came from a different school. I had consciously modeled myself after an older generation of actors, and although I had nothing against the Method, which involved summoning personal memories to authenticate emotions in a given scene, it didn’t particularly work for me.

I thought then and I think now that actors should be able to rely on their imagination—one of the most important things in life. I also believe that every talent needs to use whatever is most effective for him or her. It’s up to the director to find an emotional through line that makes sense of all the differing techniques and aims that the cast in a particular film embodies.

I needn’t have worried about Joanne. Between scenes, she would sit and knit. While she knitted, she would think about her character and the scene she was about to shoot. She would fall into a neutral state in which her own personality receded and the character edged closer and closer to her. Gradually, finally, the character took up residence.

Joanne knew who she was, she knew how to make her process work for her in a manner that freed her up instead of locking her down. She never tried to convince anyone else that her way was the way. There was no stress or strain to how Joanne worked. Acting with her was a great experience.

She was born in Georgia, and she always had a trace of that soft Southern touch in her voice. Joanne was one of those huge talents like Meryl Streep—she got to the top quickly, and without any sense of strain. She was an understudy for several parts in the Broadway production of Picnic, which led to some TV work. She made her first movie when she was twenty-five, and her second was A Kiss Before Dying. You never would have known she was at such an early stage in her career; she was incredibly centered for a young actress—an old soul. After our picture, she got her Oscar for The Three Faces of Eve, married Paul Newman in 1958, and was off on a stellar career and, far more important, a stellar life.

I’ve never worked with Meryl Streep, but I know people who have, and they tell me she’s a lot like Joanne—a great talent that bloomed early, and also something a little more unusual: a quality temperament that makes her a pure pleasure to work with. She’s liked within the business and without, which is one reason she’s had such a remarkable career; she’s respected for her talent and liked for the woman she is.

Joanne married a man who was professionally like her in many ways. Paul didn’t use his technique as something to set him apart, or as some sort of status symbol. He was more obviously given to dissecting the arc of a character than she was, but he was also insistent on being one of the guys.

Paul and Joanne had one of the greatest marriages I was ever privileged to witness. Not greatest show-business marriages—greatest marriages, period. Joanne’s ambition extended far past her profession; she wanted to be responsible and responsive to all things. Most obviously, she had a commitment to her children. The great gift she and Paul shared was a lack of overwhelming ego; they had no pre-conceived ideas of who they were as actors. They both understood that careers are like smoke; at different times in your life, your career is going to waft in different directions, and not all of them are going to be positive. Most of it has little to do with who you are as a person or even as an actor, but that’s easier to accept in concept than it is to live with when the scripts aren’t arriving or the ones that are arriving are terrible. Both Paul and Joanne were completely secure within themselves. Paul never sweated if a picture or two failed; he figured that the next one might hit, and everything would be all right.

I worked with Paul and Joanne in 1969 in a good picture called Winning, and that was the beginning of a solid friendship. They confirmed my own sense that the best way to survive the vagaries of show business is to have a life outside of it. There is no finer example of living that principle than Paul and Joanne. They worked in the theater, they started up the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp for seriously ill kids, and Paul established the Newman’s Own line of food products that has churned out hundreds of millions of dollars for charity.

Joanne Woodward

Paul continued his career on a very high level until just a year or two before his death in 2008. I stay in touch with Joanne to this day. She remains a woman to admire and love.

• • •

Lauren Bacall became a star in her first film, To Have and Have Not, by channeling some of Marlene Dietrich’s quality of bored hauteur. Dietrich wasn’t going to pursue a man—she would simply indicate her interest, and if he was too dumb or square to do anything about it, she’d move on to the next guy.

Bacall had never acted before, so Howard Hawks had to trick out a personality for her in that first movie, and he directed her beautifully. Bacall projected brilliantly in her scenes with Bogart, so when they got married a few years later, the marriage made a lot of sense; they had an ease with each other and great on-screen timing that made you believe the marriage must have been a lot of fun.

This is emphatically not always the case with real-life married couples—Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton had a roaring affair that led to not one, but two unsuccessful marriages. Burton’s diaries attest to their real-life sexual chemistry, but they never really struck sparks on-screen, and there were times, such as in The Comedians, when their love scenes were terribly phony. The same thing happened with Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman.

Sometimes it photographs, sometimes it doesn’t.

• • •

By the 1950s, leading ladies weren’t just marginalized, they were endangered. To take just one obvious bellwether: Every year since 1932, the trade paper Motion Picture Herald had been putting out a list of the top ten box office stars. In the 1930s, women reliably held five or six of the top ten spots. By the 1940s, the average had dropped to about four, and in the 1950s, two. In 1957, no women appeared on the list at all. In the early 1960s, Elizabeth Taylor and Doris Day consistently charted, but the fact remains that the audience and the industry as a whole became far more interested in men than women.

But then, everything in the film business turned upside down in the 1950s, although the events that led to the crash originated in the previous decade. The government won an antitrust suit against the movie studios that forced them to sell off their theater chains, which the government said made them a monopoly. This meant that the studios lost an entire profit stream.

Simultaneously, TV started draining away the audience. By the mid-1950s, you could see the studio system was falling apart. Some of the independents hung on—Disney, Goldwyn—but they didn’t do mass production. Rather, they were more like independent jewelers; each of their pictures was handcrafted.

RKO went out of business after a decade of Howard Hughes’s mismanagement. Darryl Zanuck opted out of running his studio; he simply burned out. He moved to Paris and went into independent production, making a picture a year instead of overseeing thirty, and Fox began to have severe problems under his successor, Buddy Adler.

Unfortunately, the pictures Darryl produced in Europe (The Roots of Heaven, Crack in the Mirror, The Sun Also Rises) didn’t help prop Fox up at all. Darryl made good on his losses when he produced The Longest Day, but there were a lot of failures before that.

Losing the theaters was a financial blow for the studios, but it was also a psychological one. If you take the long view, it’s obvious that the movie industry has always been resistant to any form of change. They’ve had to be dragged kicking and screaming into every new era.

In the nickelodeon days, they didn’t want feature pictures, only shorts. In the silent era, they didn’t want sound. Then they put off color as long as they possibly could, and then came the civil war with television. More recently, we’ve seen the revolution in digital production—the one change the industry did leap into, simply because it meant a vast saving of money.

It’s a mark of how psychologically conservative the movie business is that no major technological change has ever been developed in-house at a movie studio. Not one. Warners rented Western Electric’s sound system; the Technicolor Corporation developed its own process and rented it out to the studios; Fox bought CinemaScope from a French inventor. And so forth. It’s always the same: A tidal wave of change that begins outside the studio walls ultimately can’t be resisted, and the studios finally capitulate.

And the tragic thing is that the studios could have owned all of it. They could have owned sound instead of renting it; they could have owned color instead of renting it; they could have owned NBC and CBS instead of gradually becoming subservient to them. And 20th Century Fox could have built and owned Century City instead of selling off so much prime real estate to raise money for Cleopatra.

Alongside the revolution that was roiling the way pictures had been made and distributed was a revolution in styles of acting and directing. Actors like Brando and James Dean worked in a different way, and there was a lot of foolish chatter about the end of “personality” acting, that the presence of Brando made actors who worked in an older style obsolete. As if you ever thought Brando was anybody but Brando.

In fact, chameleon actors like Paul Muni or Daniel Day-Lewis, performers who can create emotionally and physically unique characters from picture to picture, come along about once a generation, if that. The reasons are basic: Actors who sustain careers for a long period of time tend to have very powerful, vivid personalities. Chameleonic actors are often strangely bland when you see them on talk shows or meet them; they don’t have strong personalities of their own, but they can expand at will to fill out large, well-written characters.

I would go so far as to say that acting, or at least movie acting, has always been and still is a personality business, which is proven by how many of the actors of the 1930s and 1940s survived rather nicely in the 1950s, in spite of the predictions of a lot of observers—people, I might add, who never made a movie of their own.

Still, the changes were sudden and brutal. Once MGM let Gable go, nobody was safe. The same was true of Tyrone Power at Fox, although by then Ty was anxious to get away and stretch his wings. At Fox, he worked for a straight salary; freelancing, he could get percentage deals. Ty told me he made a lot more money from a very ordinary Universal picture called The Mississippi Gambler than he had ever made for a movie at Fox.

Lana Turner had been a huge star in the 1940s, but sailed right through the 1950s with some huge hits like Peyton Place and Imitation of Life after being cut loose by MGM when they were going through one of their periodic convulsions.

She didn’t have a particularly good reputation as an actress, but the affection I had for Lana as a person took precedence over concerns about her level of talent. In fact, I thought she was quite good in The Bad and the Beautiful, not to mention a movie George Cukor directed called A Life of Her Own, which not enough people know about.

But it’s probably true that Lana needed it all working for her—a good script, and a good director to motivate her. But then, doesn’t everyone? The problem was that MGM was only occasionally interested in giving their stars that kind of consistent support; their stars were expected to pull the weight of mediocre scripts and directors as a matter of course. That’s why Clark Gable is primarily remembered today for two pictures: Gone with the Wind and It Happened One Night—both made away from MGM on loan-out.

Lana was one of those women who got into the movies very young—probably too young. The movies were all she really knew, and sometimes it showed in some of her naïve choices in men—seven husbands, eight if you count two marriages to Stephen Crane, not to mention affairs with Ty Power, and the late, unlamented Johnny Stompanato.

Her background was similar to Crawford’s or Monroe’s—an impoverished upbringing, with a missing father. Making it in the movie business was supposed to make good on all the emotional and financial deprivation of their childhoods.

Supposed to.

Lana Turner

Lana was born Julia Jean Mildred Frances Turner (her family called her Judy) in an Idaho mining town. Her father was a gambler who was beaten to death in a robbery involving his stash of money. Her mother was working in a beauty parlor, so Lana was boarded out to a family that treated her badly.

If all that wasn’t grim enough, along came the Depression. Just when things couldn’t get much worse, Lana and her mother moved to Hollywood, if only because they figured it was better to be warm and poor than cold and poor. Lana enrolled at Hollywood High, and one day in January 1937, she was sitting at a drugstore—it might have been Schwab’s, at the corner of Sunset and Crescent Heights, on the south side, and it might have been someplace else. The legend, as spread by the columnist Sidney Skolsky, says that it was Schwab’s, but you have to be careful about how much trust to put in legends.

What Lana told me is that she had cut classes at Hollywood High—she never claimed to be a scholar. Billy Wilkerson, the publisher of the Hollywood Reporter, spotted her, and his eyes zoomed out of his head like the wolf in a Tex Avery cartoon.

And then Billy popped the Question: “Would you like to be in the movies?” (This has always carried far more weight than the conventional question about getting married.)

Judy was young, she was quite beautiful, and she had a body that men would go to war over. Her answer was basic: “I don’t know. I’d have to ask my mother.”

Since the family was still in search of something that would float their lives, Mom thought it was a great idea. Billy took her to Zeppo Marx, who had quit the family comedy act to become an agent. Zeppo brought her to Warner Bros., where Mervyn LeRoy changed her name from Judy to Lana, and showcased her bouncing down the street in an unforgettable shot in They Won’t Forget when she was all of seventeen. When Mervyn left Warners to go to MGM, he took Lana with him. She was a particularly valuable addition to the studio—with the exception of the late Jean Harlow, MGM was not really in the business of sexy, but they were about to be.

Lana went to drama school, and she was carefully placed in films where she would be noticed but wouldn’t have to carry much dramatic weight—an Andy Hardy vehicle, a Dr. Kildare, some other B-level movies, then some musicals. Ziegfeld Girl moved her out of the promising class and into the big time. Busby Berkeley staged the musical numbers, and then there was the cast. In order of billing, they were: James Stewart, Judy Garland, Hedy Lamarr, and Lana Turner. MGM showcased her impeccably: In 1941, besides Ziegfeld Girl, she made Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—as the good girl!—Honky Tonk with Clark Gable, and Johnny Eager with Robert Taylor.

Lana’s attitude toward all this was simple: Why not? As she would say, “There were girls who were prettier, more intelligent, and just as talented. Why didn’t they make it? It’s a question of magic. You have it or you don’t, I guess.”

From the beginning, Lana had that specific ability that is common to almost all great movie stars: She was open to the camera, by which I mean it didn’t scare her.

By the time she made The Postman Always Rings Twice in 1946, she was only twenty-six, but she’d been a star for nearly ten years. I like her performance in that film. She downplays the emotion, just as the character would in real life—a woman with that kind of sexual power doesn’t really have to do much more than just be. Look at the man and see him react. Be a trifle uninterested. Watch him grovel.

And costuming her all in white—and in shorts!—was a master stroke of design, one that contrasted strongly with John Garfield’s darkness and street good looks. Throughout the 1940s Lana reigned as Hollywood’s primary sex symbol. Even though she had more flops than hits in the following decade—middle age is always difficult for sex symbols—the hits were considerable.

Lana’s problem was that she became known more for her life offscreen than on-screen. Specifically, her marriages began adding up. Lana’s belief system when it came to men was simple: “If you want a blueprint, here it is: lose one love, snap right back and catch another.”

Her first husband was Artie Shaw, whom she wed when she was barely twenty. That lasted all of four months.

I believe that Artie took it upon himself to educate her—Artie had a terrible Henry Higgins complex, which accounts for why none of his wives (a group that included Ava Gardner) hung around long. Artie’s invariable presumption was that his girl or wife of the moment was always dumber than he was, and nobody likes to be slotted into that category, even if it happens to be true.

After Artie came Stephen Crane, by whom Lana was already pregnant, only to find out that Crane’s first marriage hadn’t been dissolved yet. They had to get their marriage annulled in order for him to get divorced, then remarry. Quickly.

That marriage lasted a couple of years and was followed by a very public affair with Ty Power. Lana got pregnant again, and was thrilled, but Ty . . . Ty was separated from Annabella, his wife at the time, but they weren’t divorced yet. It was 1947—there weren’t a lot of options.

Ty told her that the choice was up to her; all he asked was that she should let him know what she decided. He left on a twelve-week airplane trip, and she got hold of him via ham radio. “I found the house today,” she told him—their prearranged code for her decision to have an abortion.

When Ty returned, Lana was fully prepared to resume the affair; she figured that when he was divorced, they would marry. But Ty first avoided her, then, when they got back together, was distant. Finally, he told her the truth—he had fallen hard for Linda Christian while he was overseas. What made the situation worse was that Linda Christian had played a very minor part in Lana’s film Green Dolphin Street.

Lana had a large emotional investment in Ty, so she took all this very hard. Ty ended up marrying Christian, who played around on him and eventually took him for a hefty divorce settlement. To the end of her life, Lana regarded Ty Power as the great love of her life, probably because he was the one who got away. I can’t imagine two more beautiful people ever cohabiting on the face of the earth.

I knew Lana best in the mid-1950s. She had been at MGM since she was a teenager, so when the studio cut her loose in 1955, it was a shock. I remember her telling me that MGM did everything for her except put the wedding rings on her finger. She didn’t know how to do such simple tasks as making a hotel or plane reservation—the studio had always done that for her. She felt like an orphan.

At that time, she was married to Lex Barker, remembered as the guy who succeeded Johnny Weissmuller as Tarzan. Lana and I got to be pretty friendly, and there was the suggestion that she was interested in me. It might have happened, but I liked Lex and didn’t want to intrude on their marriage.

The word around Hollywood was that Lana was a semi-nymphomaniac, and that might have been true. She did like to have a good time when she wasn’t working. She drank, and even though she was never an alcoholic, she aged at a faster rate than was necessary. When she was forty, she looked fifty, and when she was fifty she looked sixty.

But Lana was fun. She had humor, she had energy, and she was always looking for the brightness in life. Lana would invite me to her parties, and I grew to adore her. Johnny Stompanato once asked me for Lana’s phone number, but I managed to dodge that particular (literal) bullet. He got the number from somebody else and moved right in on her.

Lana once told me that she didn’t like sex anywhere near as much as she liked romance—the candlelight, the soft music, the seduction. I think it was true for her, and for a lot of women. And if you think about it from the point of view of a female movie star, it makes perfect sense: They’re hit on all the time—everybody wants something from them.

There has always been a very predatory attitude about women in the industry. Once, when I was preparing to leave the country to make a movie, I asked the director if he was going to take a cruise ship overseas.

“No,” he said. “All the best pussy flies.” I’ve never forgotten the remark, and the unpleasant edge it contains. It bothered me at the time, and it bothers me even more now that I have three daughters.

Even if people aren’t after women stars for sex, they’re after them for their time, their name on the dotted line. Rarely are they pursued for their value as people.

Think about what a burden it must be to have to own every room you walk into. And even greater than that, to worry about what the close-ups reveal—every day that ticks by makes it that much more difficult to sustain the illusion of youth. That’s why cameramen of that era always used some level of diffusion when shooting women, unless the story mandated that the actress in question had a scene in a drunk tank. One cameraman told me that Tallulah Bankhead told him to shoot her “through a Navajo blanket,” and she was only half kidding. Tallulah drank—a lot—and she needed all the help she could get.

To counter the pressure they faced from the industry and from themselves, many of the actresses adopted a businesslike brusqueness, while some had much harder shells—a don’t-fuck-with-me-boys attitude. Survival mechanisms, pure and simple.

So many actresses wind up marrying their agent or their bodyguard—for protection, either psychological or literal. Of course, such unions can come apart quickly when the woman asks her agent/husband for advice about which film to do, and the recommended film bombs. Then the trust begins to falter, because the protection the actress imagined she was getting falters. And the cycle starts all over again.

A lot of the actresses I knew married men who were on a lower social or economic level than they were, because they were the guys who reacted to them in an honest and open way. That might help explain Elizabeth Taylor’s final husband, whom she met in rehab, a choice that would otherwise have seemed evidence of temporary derangement.

So it was that Lana gravitated toward a guy who seemed to know it all—the gangster Johnny Stompanato. When Lana’s daughter Cheryl Crane stabbed him to death, the newspapers went berserk; Lana’s life had become inseparable from Lana’s movies. She made more films after the scandal, and some of them were quite successful: Imitation of Life was probably the biggest, and the best, although it makes veiled reference to the Stompanato case. Lana plays an actress who wants her daughter to have the best of everything, but is too busy with her career to actually give her much attention.

Lana kept making movies well into the 1970s, played around with television a little, and then seemed to enjoy not working. It’s not a surprise; she’d been supporting herself since shortly after she hit puberty. I rather like what Adela Rogers St. Johns said about Lana: “Let’s not get mixed up about the real Lana Turner. The real Lana Turner is Lana Turner. She was always a movie star and loved it. Her personal life and her movie life are one.”

But why shouldn’t she have loved it? She was a gambler’s child, tossed out into the world without any sense of personal identity beyond the need to survive. And survive she did. Sometimes messily, sometimes gloriously, but she lived a star and died a star. That is how she wanted to be remembered, and it is how she is remembered. Add to that her immense kindness and generosity as a person. Put it all together and in my book that makes Judy Turner’s life a far greater success than she ever could have imagined at Hollywood High.

• • •

Like any other period, the 1950s had its good points and its bad. The bad points were somehow more obvious. For instance: the blacklist, that period when even nominal liberals had their careers destroyed or imperiled because of their politics. I know all about it: When my picture Prince Valiant opened, it got picketed because the man who wrote it, Dudley Nichols, was a liberal, or, as they’re called now, a progressive. In fact, the picture should have been picketed because of the wig I had to wear. Had anybody asked, I would have been happy to organize the protest.

Dudley Nichols was never a Communist, never even close to being one, and everybody in the movie business knew it, which is probably why he managed to keep working. But he was seriously threatened by the American Legion’s picketing.

The 1950s were also a period that witnessed a more openly erotic approach by female stars. Marilyn Monroe would never have been accepted in the 1940s, even though there was a healthy amount of self-parody in her image. I always thought Marilyn helped herself to aspects of Mae West’s personality, but instead of Mae’s self-awareness, Marilyn pretended to obliviousness. The characters she played were usually unaware of their attributes, even as they were flaunting them.

Contrary to general belief, the great sea change in the impact of female beauty was not really due to the easing up of censorship and the gradual increase in nudity, first in films coming from Europe, and later in domestic movies. Rather, it was the product of a technical development: the widespread adoption of color. Great stars like Greta Garbo, or, for that matter, Norma Shearer, existed in a black-and-white world, and it served them well because that was all there was.

But when color came in in a big way in the 1950s, when you could see the creamy complexion, the green-blue eyes, and flaming lips of stars like Ingrid Bergman, comparatively decorous black and white seemed archaic, sexually speaking. Color eroticized women, and it freed up male fantasies. It also enabled actresses to emphasize an aggressive sexuality that black and white had only hinted at. Certainly, Marilyn in black and white had about half the impact of Marilyn in color, up to and including Some Like It Hot.

And despite the stylization of color—red in the movies was invariably redder than red in real life—it also made the movies seem more real, continuing a series of innovations that had moved the art from the silent days. Sound gave the movies dialogue and natural sounds, water rushing, car motors revving, guns firing—all of which made the movies seem more a depiction of actual reality, even if the plots were outright fantasy.

Color reflected the way we actually see the world, while the influence of European actresses like Anna Magnani, Sophia Loren, Brigitte Bardot, and Gina Lollobrigida also helped. Sophia was beautiful, of course, but she was also real, as was Magnani. These were women of intense flesh and blood—magnificently so.

But at the same time color made it more difficult for older actresses who had built their careers on their glamour and beauty, because it was harder to hide their age in color than it had been in black and white. Loretta Young only made a few color movies, and she liked it that way. Her move into television meant she could stay in a black-and-white medium, which is yet another reason why the movies began moving resolutely toward color throughout the decade—it was a selling point, just as expensive locations and widescreen spectacle were. They were all things you couldn’t get on TV.

Some actresses reflected this trend more than others. Audrey Hepburn always seemed real in spite of the fact that she wore Givenchy because she embodied a strong emotional reality. So often there was a sadness about Audrey. Marilyn was a fantasy; Audrey was real. Both glorious; both transcendent.