THE EIGHTIES (AND ON)

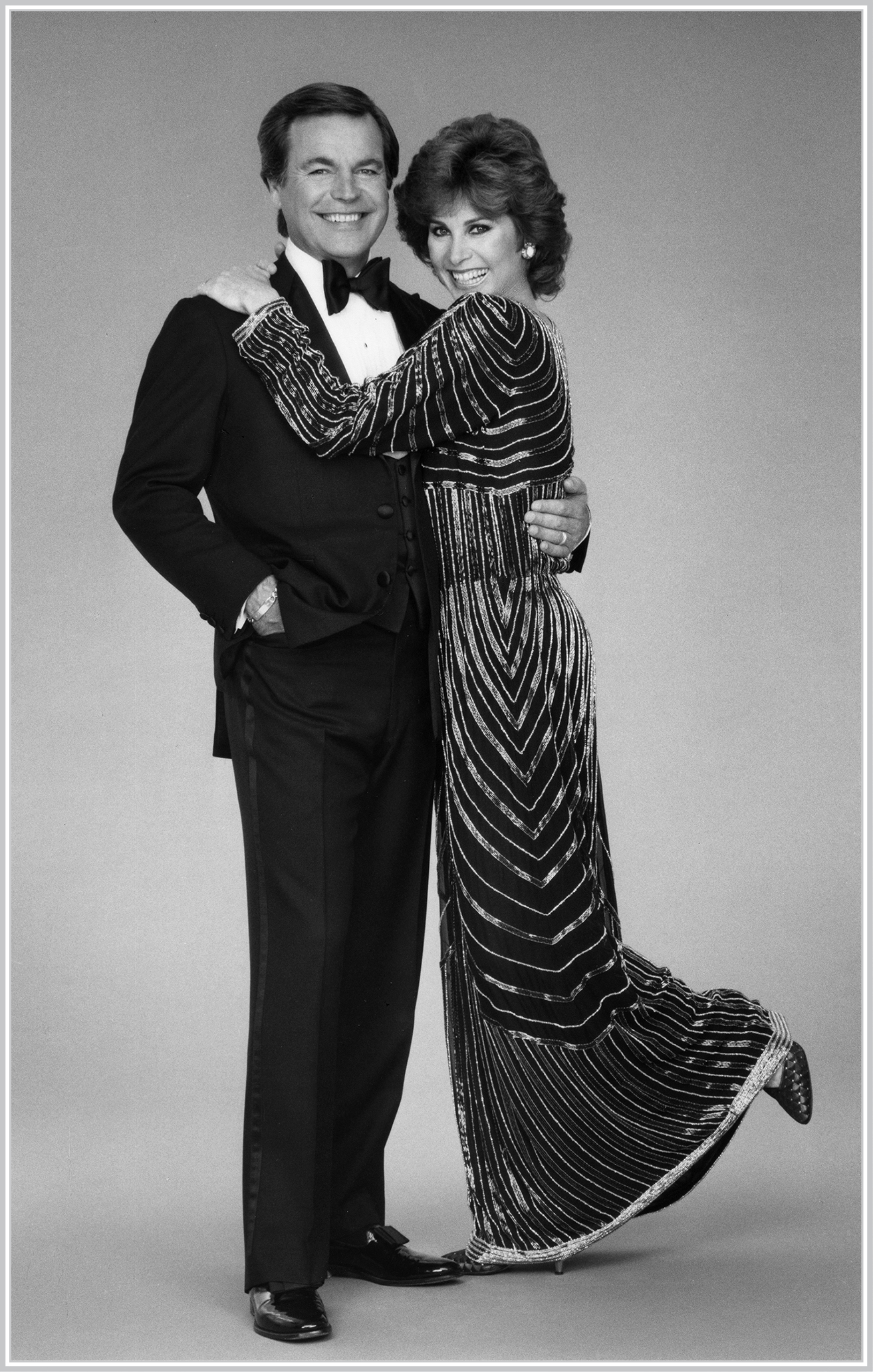

No discussion of the actresses I’ve worked with would be complete without Stefanie Powers. In my memory, there are so many ironies connected with her. Nobody wanted her for Hart to Hart, except for Tom Mankiewicz and me. Stefanie had had a major flop with The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. years before and the TV business had never forgiven her.

As for ABC, their preferences were, first, Natalie—a total nonstarter, because we would have had no private life at all—and second, Lindsay Wagner. They thought the tagline “Wagner and Wagner” was just too good to pass up.

I thought they were idiots.

But Stefanie and I had worked together a few years before, and I knew that we meshed. Her timing complemented my own. Finally, it got down to my saying, “It’s her, or there’s no show,” and since I held a lot of cards at that time, they gave in.

Irony number one.

Then we made the pilot, and Sidney Sheldon took his name off the show as the creator. It was Tom Mankiewicz who was ultimately responsible for so much of the success of that program. He rewrote Sheldon’s script for the pilot, and when it went to series he ran the show.

In any case, Sheldon put his name back on the show after it became a big hit. In spite of the fact that it was widely thought to be a potential smash—Aaron Spelling and Leonard Goldberg didn’t make a lot of bombs—getting it on the air was a tortuous process, but it never showed in the final product.

Irony number two.

To this day, people think that Stefanie and I were actually married, or should have been. Of all the dozens of actresses I’ve worked with, Stefanie is the one people most often associate with me. The truth is that the success of the show was a tribute to the mysterious nature of screen chemistry. Stefanie and I meshed beautifully as actors, but we’ve never had that much in common as people; we’d do the work and then go our separate ways.

Irony number three.

If you think about great screen teams, they were rarely emotionally involved. Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn lived together for years, but William Powell and Myrna Loy were just friends.

I think it’s entirely possible that marriage gets in the way of a successful screen pairing, simply because a husband and wife know each other too well to provoke any sense of genuine discovery.

Stefanie was always a pro—she knew the script, she did her own makeup, and she was on top of every detail, so much so that there were times when she also would have been happy to write, produce, and direct the show.

She had a sense of lilt, of humorous delicacy in her characterization, and she also had that touch of class that went with the show’s premise—the flowers, the Rolls-Royce, the level of production that Aaron and Leonard gave us. I can honestly say that Stefanie never disappointed me as an actress. She was the perfect Jennifer Hart—humor, intelligence, amazing looks. She made a tremendous contribution to the series’ success.

Stefanie Powers

Of course, actors are helpless without good writing, and that’s where Mart Crowley and Tom Mankiewicz came in. Mart had worked for Natalie when he was a young man, and he came back to work with me after his huge success with The Boys in the Band. Mart wrote the relationships and the patter on Hart to Hart, which sounds easy until you try to do it. I always pined for a pair of writers who could be the TV equivalent of Billy Wilder and Charlie Brackett, but for some reason writers don’t like to collaborate anymore, so the plots would be done by one writer, and the dialogue by Mart.

The production process was fairly typical; we’d take seven days to make an episode, and they were long days—ten hours occasionally, twelve hours regularly. After that, we’d head home, have a meal, go over our lines for the following day, and go to bed.

One-hour TV shows devour your life, so it’s mandatory that the working conditions be as stress free as possible. You don’t want people around you who impede the mechanics of the process. If someone on the crew wasn’t happy, I would talk to them once. If the person was still a problem, they were gone. After a year or two of the show’s success, writers would begin to agitate to be promoted to producers, because producers make more money, so there is always the matter of negotiating careerist jostling.

When I went back to work after Natalie died, I was so filled with anxiety. Stefanie came into my trailer and said, “You’re going to be all right.” And she took me by the hand and led me to the set. I don’t know if I could have walked there myself. She was there for me. Leonard had closed the company down for almost a month, and when Stefanie and I appeared, the entire crew offered their warm support.

Stefanie was with Bill Holden then and until his tragic death. He introduced her to the glory of Africa, which was his great passion and which became hers. Their enthusiasm gradually grew; Bill was a great guy, a man’s man and a ladies’ man as well, but the two of them could clear out a room talking about zebras.

After Bill died, Tom Mankiewicz fell under Stefanie’s spell and built a house next to hers in Africa, but the relationship didn’t work out.

Years after Hart to Hart went off the air, Stefanie and I reunited for a batch of TV movies, and the chemistry was still spot on.

Now, I see Stefanie when the Museum of Broadcasting or a TV show wants to do a Hart to Hart reunion. Just as we did thirty years ago, when the lights switch off, we head in opposite directions, but I will always be grateful to her for the radiant personality that made our show the first-rate entertainment it was. And I will never forget her strength and kindness in the worst moments of my life.

• • •

Audrey Hepburn holds a special place in my heart, and always will. I have a picture of her as a little girl, and she had the same adorable face and nature then that movie audiences everywhere would come to love.

Audrey had the most fantastic spirit of any woman I’ve ever known. You can look at a picture of her when she was three years old and see Audrey clearly. I’ve encountered only one other woman who had that quality: Elizabeth Taylor. We all have different aspects of ourselves that we reveal, depending on circumstances. Sometimes we’re soft and yielding, and sometimes quite the opposite. But Audrey had no façade; she was consistently Audrey in every aspect of her life.

And there was something else—she absorbed everything that life put in her path, and then reflected it back to the world, concentrated and doubled and transformed into beauty. The flowers that filled her house in Switzerland, the fabrics on her furniture, the fashions she wore—all combined to create a sense of a unified personality in the way that nature often does, but that is seldom found in human beings.

Beneath Audrey’s surface was a sense of sadness, which I believe was caused by her sensitivity to life and to other people. She understood on a fundamental level that life is often unfulfilling at best and tragic at worst, and she carried that with her as a counterweight to the fulfillment her beauty and talent earned her. She put everything she had into UNICEF, but that was typical—if Audrey committed to something, it was with her whole heart.

I might add that Sophia Loren has some of that same sensitivity; they both grasped what you were feeling, sometimes before you did. In both cases, I think early poverty might have been the cause. Certainly, young Audrey being subjected to the Nazi invasion of Holland had a tremendous impact on her psyche.

Audrey was confronted by the impermanence and instability of the world, and that knowledge accompanied her everywhere she went, even as she tried to compensate for some of that insufficiency. Both of her marriages failed, through no fault of her own. This affected her deeply, until she found great happiness with Rob Wolders late in her life. Rob was also Dutch, and they had much in common besides their nationality.

I first met Audrey when I went to Europe to do The Mountain with Spencer Tracy. She was married to Mel Ferrer at the time. Mel had a good sense of humor, but could be slightly remote. I was immediately struck by Audrey’s beauty, as everyone was, but her personality was every bit as attractive as her face. She was shy by nature, but tried to be open. Years later, we did a TV movie together, one of the last things she did before her death.

As an actress, Audrey knew her work. She moved her process out of the way in order to let her being come through, and it was her being that made Audrey special to the world. She was a magical presence.

In reading over this, it sounds as if I had a crush on Audrey Hepburn. Well, why should I be any different from everybody who ever worked with her? Why should I be any different from the rest of the world?

• • •

Beginning in the 1970s and continuing through the 1980s, I did more TV than film. I found that I liked the rapid pace of television, but there is a cost to speed, and that relates to the overall emotional experience of the production process.

Audrey Hepburn

A movie takes eight weeks, sometimes longer, so you might be working with a given actor or actress for months at a time, which means you really get to know them. It’s not just a matter of the hours spent in rehearsals and the performance, there’s also a lot more downtime while you’re waiting for the lights, or moving from one location to another. Just having the opportunity to sit around talking to and asking questions of actors I spent my youth watching was always one of the greatest perks of the business as far as I was concerned.

But TV moves very quickly—on Hart to Hart, I might work with guest stars for three or four days, which didn’t allow for a huge amount of leisure to get to know them. But some of them do stand out in my mind. I’ve mentioned Joan Blondell and a few others, but I also want to pay tribute to Dorothy Lamour.

Dotty was one of those performers whom everybody liked—other actors, the crew, the front office, everybody. She had been a huge star before, during, and after World War II in South Sea movies like John Ford’s The Hurricane, the Bob Hope and Bing Crosby Road pictures, and so forth. Her last big picture had been DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth in 1952, after which she had more or less retired.

She married a man who lived in Baltimore, had some kids, and enjoyed her second career as a wife and mother. She toured in Hello, Dolly! and dinner theater in the 1960s and 1970s, but hadn’t been doing a lot of TV or film work when she came on Hart to Hart, so I really had no idea what to expect.

I needn’t have worried—she knew the script cold. It wasn’t The Hurricane, but if she felt any disappointment about doing television, she didn’t show it. She was still miffed about Bob and Bing; she felt they had given her short shrift over the years, and not taken her contributions to their films seriously.

If Dotty felt that she had been put on the shelf after she got to be a certain age, she didn’t let it spoil her pleasure in the work she still had. When she died, her family asked me to give the eulogy for a very classy lady.

In retrospect, Dorothy Lamour’s experience was symptomatic of an abiding show-business trait, one that persists even today.

As I’ve discussed earlier in this book, forty can be difficult for any woman, but in show business it’s especially difficult. An actress like Meryl Streep, who sails into her sixties still playing the few leading parts for women of her age, is the exception; she’s the American equivalent of British actresses like Vanessa Redgrave or Maggie Smith, who will work as long as they can stand up, and when they can no longer stand up will work sitting down. They’re that good, and they’ve also formed strong, lasting bonds of affection with audiences.

And there’s another issue, which is the nature of the industry itself. Audiences used to be heavily invested in their female stars because the studios themselves had invested in those actresses. They were presented with all the glorious lighting and dramatic impact possible. And the audience responded. Those backlit, erotically charged close-ups had impact. They still do.

But women aren’t presented that way anymore; they seldom have that kind of erotic power, and if they do, they don’t have it for long. The few real female stars are in perpetual transit from one studio to another. Stars today are actually highly paid migrant workers, or, if you prefer, independent nation-states; they have nobody to look out for their interests but themselves and the people with whom they surround themselves.

Add to that the fact that the media surrounding celebrity has never been more carnivorous than it is today, and what you have is a recipe for shortened careers. I’ve mentioned the brief runs that stars like Betty Hutton had, and the truncated professional life of someone like Ann Sheridan. But even then, Betty Hutton had ten good years, and Ann Sheridan had slightly more than that, runs for which a lot of modern actresses would consider bartering a child.

That underlying reality of the movie business can be summed up by the famous remark of Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr: The more things change, the more they remain the same.

• • •

In 1988, I did a remake of a Cary Grant/Ingrid Bergman picture called Indiscreet, about a middle-aged love affair. I wanted to do it with Candice Bergen, but CBS wouldn’t hear of it. I kept agitating for Candy, but it got to the point where the network said they would not go forward with the project unless we dropped the idea of Candy as my leading lady.

Over and over they explained their reasoning, as if I was slightly dim: “She’s an ice queen. She doesn’t have a sense of humor.”

So the network gave me Lesley-Anne Down, who proved to have no affinity with me or anybody else whatsoever. A year or two later, Candy got Murphy Brown—a CBS show, I hasten to point out—and the woman who had no sense of humor was off and running in one of the great sitcoms.

I see Candy and her husband whenever I go to New York, and she remains one of the most delightful women I’ve known. Had she done Indiscreet with me, I have no doubt that the result would have been something special. As it worked out, if you mention Indiscreet, people think of Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman . . . as they should.

This is the sort of thing that makes show business so crazy, and it became just a little crazier as TV became increasingly important—eventually more important—than the movie business. Because there’s more work in TV, there are many more slots for actors, so the talent pool becomes bigger. Unfortunately, so does the lack-of-talent pool, as I found out in the case of Indiscreet.

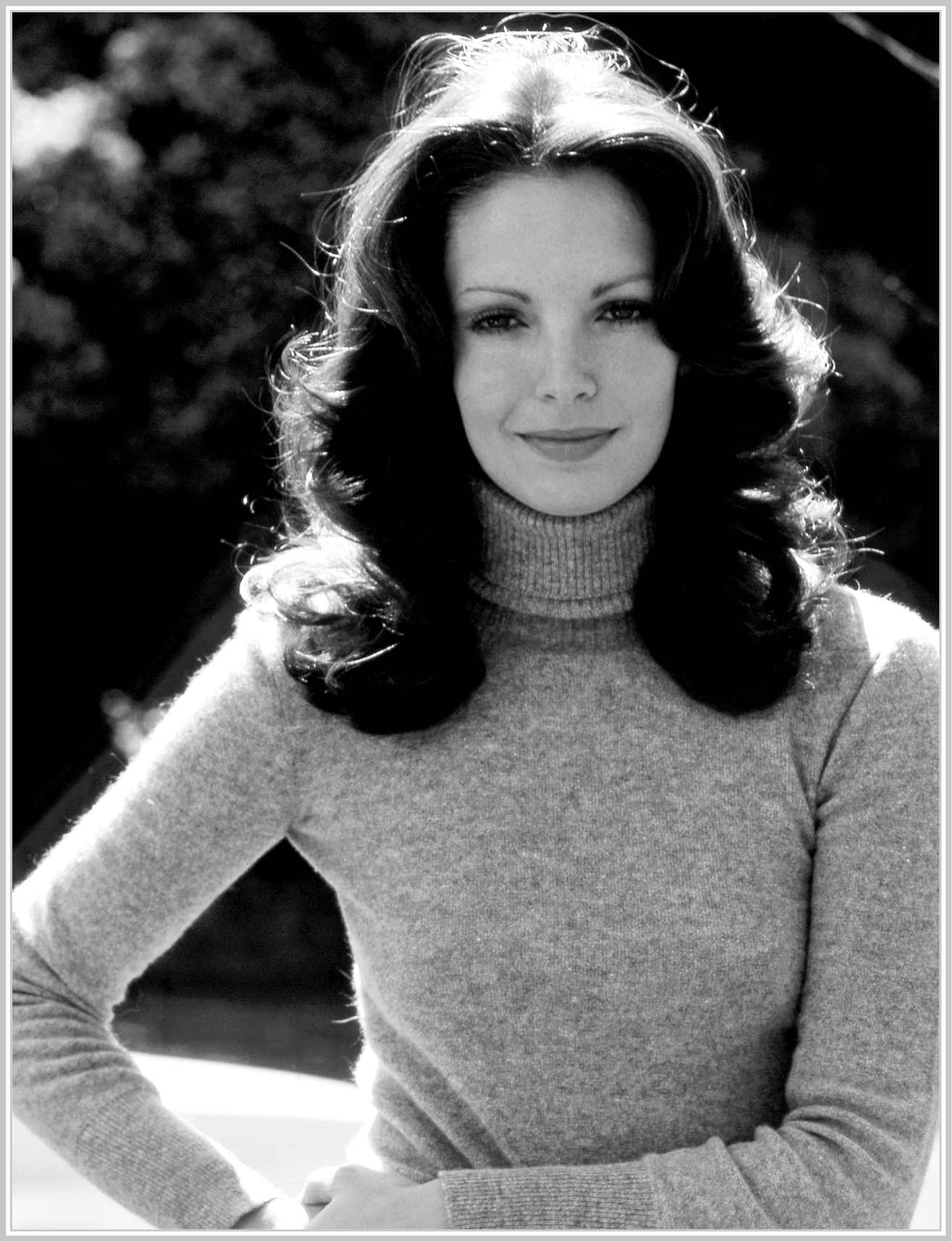

But quality does have a way of sustaining itself. Take Jaclyn Smith, easily one of the finest women in the business, and widely loved. Jackie is steady, humorous, a hard worker. She backed away from acting to occupy herself with business and charity work, but whenever I see her I’m glad I did. She’s one of those people who’s a thorough pleasure to be around—a special woman. And she can make me laugh like few people have.

Jackie came to fame and fortune on Charlie’s Angels, on which Natalie and I had a healthy profit percentage. I got her the part in that show. She had recently worked with me on an episode of Switch, shot in Las Vegas. She played a cocktail waitress, and the local news station covered the scene we were shooting. We got back to the hotel, and there was a call from Dean Martin. He wanted to meet her. I told her about it, but she didn’t want to go there.

Jaclyn Smith

I was impressed with her, and took her to meet Aaron and Leonard, who ended up signing her as one of the Angels.

And there are a few more unforgettable women I have to discuss before closing.

I got to know Julie Andrews through my friendship with her husband, Blake Edwards. Blake cast me in The Pink Panther, and we remained friends over the years. Blake and Julie had a place in Gstaad, and they hosted my family many times, usually for the holidays. There would be other close friends there—Audrey Hepburn and Rob Wolders, and Robert Loggia—God bless him—and his wife.

With Julie, as with so many of the women in this book, what you see is what you get, and that is always an amazing quality in anyone. If I had to sum her up in one word it would be empathy, which I think is something you’re either born with or not. She’s interested in the emotional and practical lives of the people she cares about, and that’s reflected in a special quality of warmth that I’ve always been drawn to. She’s always been very family oriented, with her kids as part and parcel of their parents’ lives, not fobbed off on nannies.

How remarkable is Julie? I knew Blake before he met Julie, and there was a considerable difference afterward. Blake had always been a ladies’ man, but that ended when he married Julie.

Seeing Julie in Gstaad was fascinating; she didn’t interfere with Blake’s energy—she let him set the general direction and followed along, but she also guided him, never letting things get too wild. Blake loved her, of course, but he also respected her instincts and let himself be directed by her.

And there’s something else that struck me about Julie, then and now: a tremendous sense of gratitude. She knows she’s talented, but she doesn’t think of herself as being especially remarkable; she believes that some of her career has been a matter of pure luck and some of it has been due to the fact that people simply like her. She gives the impression that she doesn’t really have any idea why that might be the case.

Consider her response when she lost her singing voice because of a botched throat operation. Julie’s identity had always been based primarily on being an outstanding singer, and she woke up one day and could no longer sing. That is a devastating development. A lot of people—most people—would be derailed if they were suddenly unable to do what had defined them all their lives. They’d go on TV and talk about their bravery in overcoming the terrible obstacle that had been placed in their path.

Julie never did anything of the kind. She absorbed the situation, then got on with her life. If she shed any tears, they were shed in private.

Nothing defeats Julie. Nothing.

Losing Blake was bad, very bad, even though we all knew how frail he was. Blake had been an aficionado of martial arts when he was younger—the karate fights between Inspector Clouseau and “my little yellow friend” Kato in the Pink Panther movies were Blake’s way of paying comic tribute to his hobby. But he had terrible back trouble for years and he had been in a wheelchair for some time before his death.

Again, Julie did her mourning in private and then briskly went about her business. She writes—a best-selling memoir, successful children’s books written with her daughter Emma—and she continues to act whenever she gets the chance.

I think Julie’s wrong about one thing: People love her for very good reasons, and she reflects that love back in all directions.

In so many ways, Julie is a blessed woman, and to have her in your life is a blessing in return.

• • •

Failure presents all sorts of problems. So does success. The difference is that the problems of failure are obvious, while the problems of success sneak up on you. If you’re an actor, success can give you financial security, but it can also fix you in the public mind in a way that makes it nearly impossible to move on, to do anything else. What started out as success seamlessly evolves into incremental frustration.

My friend Florence Henderson illustrates this principle. Florence was a star on Broadway, in the Joshua Logan production of Fanny—a great show with an exquisite score by Harold Rome. She’s also starred in movies (Song of Norway) and done good work in dozens of television shows, not to mention appearing in a smashing nightclub act. She’s also sung the national anthem at the Indianapolis 500 more times than anybody else in history.

But most people only remember her for The Brady Bunch. Granted, this is better than not being remembered at all, and I’m sure Florence is grateful for all the opportunities she’s had because of the show, but it’s still locked her into a public image as the bright, ever cheerful, always competent mom negotiating the adolescent squabbles of Jan and Marcia.

Years after The Brady Bunch, Florence did an episode of Hart to Hart with me, and after that we would occasionally encounter each other around town. The more I saw her, the more I grew to respect her. Florence always had talent, but she never had it made. She was one of ten children, grew up poor, and sang at outdoor markets for spare change.

About twenty-five years ago I found myself on the same plane as Florence at a time when I could feel myself slipping into depression. Depression can involve personal issues, things like professional frustrations—that is to say external, more or less rational causes—or it can be part of your chemistry or your biorhythms and have nothing to do with any objective reality.

I had just enough experience with depression to know how crippling it can be. You can feel the fog gathering, then darkening. First it gradually obliterates your vision of the world, so that all you can see or feel is the fog, and then it moves on to your navigational skills. You can’t get away.

I went over to say hi to Florence, and in the course of the conversation I told her how I was feeling, after which I complimented her on her own level of positive energy. She waved the compliment aside and said, “I’ve had a lot of help.” And then she began telling me about a woman who had helped her through various crises through hypnosis.

I had used hypnosis once or twice before, mainly to cope with a bad case of stage fright. Florence suggested that it might very well help me forestall a full-scale bout of depression, and she gave me a referral. The trick with any medical professional is to find someone you can relate to and trust, and I immediately felt comfortable with Florence’s friend Cheryl O’Neill.

Before Cheryl puts you into the hypnotic state, you talk to her about the issues that are overloading you—what you’re anxious about. You’re lying down, with your eyes closed and with a blanket over you. Cheryl will instruct, “Take three deep breaths. You’ll feel your feet relaxing, your legs, your knees.” You visualize coming down a series of stairs. When you reach the floor, you turn to the right. At that point, sometimes you drift off into something that feels like sleep, while other times you’re fully conscious and aware of what’s being said in the room.

After Cheryl puts you under, she addresses your issues. Sometimes after you come out of it, you can feel an immediate sense of relief, while other times it takes a little longer. After I’d been going to Cheryl for a while I found that I could hypnotize myself in order to deal with basic problems like insomnia, or even to moderate negative impulses like impatience and anger. Hypnosis has proven good for my concentration, and great for my imagination.

What I didn’t realize at the time is that most analysts use hypnotism at one time or another, on one patient or another. A lot of athletes use it, especially those who need to maintain focus over a lengthy competition in which they’re basically isolated, such as golfers and baseball players. I also know a number of singers who use it, not to mention actors, as completing a few minutes of usable film over an eight- or ten-hour workday requires more concentration than a lot of people can supply all by themselves.

As I’ve gotten to know Florence better, I’ve come to realize that she is a genuinely interesting woman, and very far from the character of Carol Brady. She’s been knocked on her behind many times and she always gets up—the most critical character attribute if you’re going to have any kind of a rewarding life.

She’s a hell of a lady who made a huge difference in my own life, and an indefatigable, magnetic personality.

• • •

It seems like I’ve known Don Johnson forever. He used to refer to me as his good luck charm because I ran into him a day or so before Miami Vice got picked up by NBC and I told him the project sounded very strong. Years after, he and Melanie Griffith bought a house in Aspen, and Don and I passed the time by playing countless rounds of golf, not to mention a lot of fly fishing.

When Melanie gave birth to their daughter, Dakota, I visited them at the hospital and was the second man to hold that beautiful child. A few years later, Jill and I were invited to Don’s annual Fourth of July party. Dakota was about four by that time, and when she saw us coming up the driveway, she took off running toward us. After a sprint of about fifty yards, Dakota came to a screeching halt and breathlessly asked Jill, “Where did you get that lip gloss?”

I told Don he had a serious problem.

All this is by way of explaining that our families became intertwined in a way I could never have foreseen when I worked with Melanie’s mother, Tippi Hedren, in an episode of It Takes a Thief. It was the period after the failure of Marnie, when Tippi was working out her contract with Universal.

At the time, nobody at Universal really knew if there had been a relationship between Hitchcock and Tippi, but we all wondered. He had clearly been besotted with her. The Birds had been a great success—I think it’s Hitchcock’s last good picture—and despite the critical and financial failure of Marnie, Tippi was by far the best thing in the picture. It’s such a strange movie; Sean Connery’s character is actually more psychologically damaged than Tippi’s, but none of the other characters seem aware of it. For that matter, neither does Hitchcock.

I knew a lot of actors who worked for Hitchcock, and, with the exception of Jimmy Stewart and Cary Grant, none of them enjoyed the experience. If you were going to act for Hitchcock, you were going to be left more or less alone. Paul Newman told me Hitchcock’s attitude toward actors was “Wheel in the meat and shoot it.” (Small-world department: Tom Wright, who’s one of the best directors at NCIS, used to be a storyboard artist for Hitchcock.)

Hitchcock was beloved by Lew Wasserman. Lew gave Hitchcock his own unit at Universal, housed in his own building, and made him very wealthy. The strange thing is that both Lew and Hitchcock tended to be cold—dust could come out of their mouths.

I worked with Melanie in Crazy in Alabama, which was directed by Antonio Banderas, whom she married after she and Don divorced. It was the first—and only—picture directed by Antonio, and I thought he did a very creditable job. Most of my scenes were shot at the Chateau Marmont, and throughout the shoot Antonio was totally prepared. He knew what he wanted out of every line of the script and every shot. On top of that, I found him to be a kind, empathetic director, probably because he was an actor long before he began directing and knew actors’ problems from the inside.

Melanie was accomplished and professional in a part that was quite a stretch for her—she played a woman who kills her husband, abandons her children (one of whom was played by Dakota), and takes off for Hollywood in search of fame and fortune, accompanied by the head of her late husband. As you can see, the title was an accurate reflection of the movie. Working with her, I realized that Melanie had a lot more on the ball than she’d been able to show professionally—she’s obviously a very sexy girl and got typed early.

Melanie isn’t particularly like her mother, other than the fact that they’re both dreamers. Tippi presents as aristocratic, while Melanie is earthier, but they share a devotion to Tippi’s great passion, the Shambala Animal Preserve.

Eventually Melanie and Antonio broke up. Melanie still lives in Aspen, and we see each other frequently, while Don has moved to Santa Barbara, which means that I lost one of my prime golfing buddies. On the other hand, I now have the possibility of working with a third generation of the family. Melanie’s daughter, Dakota, has obviously got a lot of talent and consistently makes daring choices.

Dakota, if you need someone to play your grandfather, I’m available.

• • •

In 2015, I traveled to Romania to make a movie entitled What Happened to Monday? for Raffaella de Laurentiis. My costars were Glenn Close and Willem Dafoe. I had known Glenn only glancingly—we were seated next to each other at a dinner party some years earlier. But even then we discovered mutual interests: Among other things, we had the same drama coach, an amazing man named Harold Guskin. Harold wrote a book entitled How to Stop Acting, the gist of which was that acting was about being rather than acting per se. Harold taught in his apartment in New York and inspired great loyalty from his students, among whom were James Gandolfini, Kevin Kline, and Bridget Fonda.

Harold taught you not only to get out of your own way, but also to find out about the other person, which could be defined as the other character, the other actor, or the person you sat next to on the train. For Harold, it wasn’t about you, it was about the character—how would the character react, in an honest way, to this situation in which he found himself? Harold and I both believed that the worst thing a director could tell you was how to “act,” because you don’t want to act, you want to be.

Harold had some similarities to Stella Adler, who taught her students how to live as much as she taught them how to act. Stella wanted them to be functioning members of society, to be alive to writing, art, everything that makes up culture. In other words, acting was not something that took place in a vacuum. To be a better actor, you had to be a better person, a better citizen. And beyond that, Harold and Stella both believed that acting was not a matter of producing a reaction in the actor, it was about producing a reaction in the audience. If the actor feels it, but the audience is left cold, what exactly has been accomplished?

Glenn Close

It follows, then, that Glenn is not concerned with stardom or power or any of the ancillary things that accompany fame. She’s all about honoring the work. She has some of the same focus and fierceness of Bette Davis and Barbara Stanwyck, and to my mind there is no higher praise for an actress. We thoroughly rehearsed our scenes at our hotel long before we got on the set, and we had several dinners together. She’s warm and ingratiating, an interesting woman with a huge amount of professional courage—Albert Nobbs, the movie in which she played a Victorian woman who lives her life as a man, was a tour de force that Glenn cowrote. It was just a little ahead of the curve in terms of the public interest in gender fluidity; if it was released today it would attract a lot more of the attention it deserved.

In so many ways, acting is a strange business. You work hard with another actor, and you become entirely open to each other. You give more than the lines; you give them yourself at that moment in time. That kind of emotional openness has to be accompanied by a great deal of trust and mutual respect, so neither of you will be tempted to take advantage of that privileged connection, either professionally or personally. Glenn Close reminds you of what acting, at its best, is all about.