~~~

THROUGH THE summer and fall of 1836, Cherokees struggled merely to survive. Early frosts in the previous year had killed off the corn crop, leaving farmers without a store of grain. Then a drought destroyed the spring planting. Hundreds of men, women, and children—white and Native American—wandered about Habersham County, in the foothills of northeast Georgia, begging for food. Indigenous farmers had long withstood the occasional poor harvest by relying on hunting to make up the difference. But U.S. citizens, fearing that the unrest among Creek and Seminole peoples would spread north, refused to sell ammunition to Cherokees. And General John E. Wool, commanding U.S. troops in the Cherokee Nation, required militant Cherokees in western North Carolina to give up their guns. At the same time, with the wars raging in Alabama and Florida, white Georgians felt newly entitled to run the Cherokees off their land, flogging them with cowhide whips, hickory withes, and wooden clubs. “We are not safe in our houses,” Major Ridge and his son John Ridge wrote to Andrew Jackson; “our people are assailed by day & night by the rabble.”1

Surveying this bleak landscape, John Ross and seven other Cherokee leaders recalled that during the congressional debate over the expulsion bill in 1830, its opponents had argued that its “secret design” was to make the situation of native peoples “so wretched and intolerable” that they would abandon their homelands. Others, and none more than the delegation from Georgia, had insisted that the measure was “founded in humanity.” Now, with U.S. troops positioned throughout the South, the Cherokee leaders took satisfaction in declaring, “Who was right, let subsequent facts decide.”2

Nonetheless, Cherokees refused to move. Federal agents, sent out to assess the value of native farms in the fall of 1836, as required by the Treaty of New Echota, recorded the quiet determination of the persecuted but resilient farmers. Tuelookee would not give his name or even speak to the valuators. Chudwelk and John Tatterhair told them bluntly that they were not willing to move. John Cahoossee’s widow “could not be made to under stand our business”—or perhaps she did not want to understand. Canowsawksy gladly showed off his farm—it was “first rate creek bottom land”—but insisted he would not go west on any terms, “unless Ross says he shall.” His resolve must have been fortified by the presence of Hogshooter and his family of eight, who had been living with him since U.S. citizens had torn the roof off their house and driven them away in 1833. Despite that traumatic experience, Hogshooter’s family steadfastly refused to register for deportation. Others, such as Sicktowa and Whiteman Killer, also reported that white intruders had driven them off their farms.3

Moving through valleys and crossing ridges, the roving valuators enumerated houses, fields, fruit trees, corncribs, smokehouses, and horse lots, unintentionally documenting the diversity and abundance of the Cherokee Nation. Jackson Duck, dwelling with his family of six in northeastern Alabama, owned a small field and a cabin with a split-log puncheon floor and a wood and rock chimney. Possum, living nearby on Wills Creek, had a single cabin and a camp. Robert Brown was settled along the same creek and owned a cabin that was 30 feet by 14 feet, along with a stable, smokehouse, storehouse, horse lot, corncrib, and exterior kitchen. Summers must have been bountiful on Brown’s farm, which had sixty-four peach trees, twenty-one apple trees, a cherry tree, and a Chickasaw plum tree. Nearby, Susannah, on North Wills Creek, owned several cabins, a cow pen, a cook camp, eight cherry trees, ten Chickasaw plum trees, thirty-eight peach trees, and forty-eight apple trees. She had twenty-five acres under cultivation, surrounded by a high nine-rail fence.4

Generally, the work of assessing Cherokee homes must have been tedious for the valuators and threatening and invasive for the families being dispossessed. The inventories are matter-of-fact, but in one instance a valuator paused long enough to appreciate the landscape, if not the plight of the residents. Crossing over a ridge in north Georgia, he was overcome by “perhaps the most splendidly striking mountain scenery upon the face of the Globe.” “An amphitheatre of probably 50 miles in circuit is formed by the Brasstown Mountains,” he marveled, “encircling a beautiful and fertile valley about 4 miles across interspersed with limpid streams and making upon the whole a picture unsurpassed and rare if ever to be equalled for the wildness and grandeur of its scenery.”5

Brasstown is a mistranslation of the Cherokee word for “New green place,” and Cherokees found the area as captivating as did the federal official sent to hasten their deportation. Drowning Bear, who lived at the head of Brasstown Creek, refused to show his property and said “he did not understand” the valuation process. John Walker said he would not enroll, did not want any money, and would remain on Brasstown Creek, where he farmed ten acres and tended eighteen peach and eight apple trees. Salagatahee refused to permit the valuator to visit his farm, stating that he would not go west. Two Dollar, though he had already been dispossessed of five acres of his farmland, also said he would not leave. Likewise, Sutt had lost six acres to an intruder but insisted he would not move west.6

The view of the Hiwassee River from Brasstown Bald, elevation 4,783 feet. The river was dammed to create Chatuge Lake in the 1940s.

The total value of Cherokee houses, fruit trees, crops, and the like, as determined by the valuators employed by the federal government, stood at $1.68 million. To this sum, the commissioners appointed by President Jackson added $416,000, their estimate of how much Cherokee property intruders had destroyed. On the other side of the ledger, they subtracted money that the federal government had advanced to the Cherokees or that private merchants and traders had purportedly loaned to them, a figure that totaled $1.35 million. That left $746,000, or about $125 per family. This paltry sum was all that Cherokee families who had cultivated farms in the region for generations would receive for their improvements. In practice, many received nothing, since their purported debts offset the assessed value of their homes and fields.7

The five leather-bound volumes that contain this reckoning are a monument to exacting procedure and moral obtuseness, as if the appearance of rigorous financial accounting would answer ethical questions about deporting thousands of families. Wilson Lumpkin, who in his fourth role after congressman, governor, and senator was now serving as one of Andrew Jackson’s two special commissioners overseeing the process, declared that nothing “but a sense of duty, and a desire to promote the interest of the perishing Cherokees” had induced him to accept the assignment. He and his co-commissioner attended to the task “with great labour” by establishing an elaborate system of record keeping, with various payment registers, valuing books, receipts, duplicate receipts, vouchers, balance sheets, and the like, all in the service of preventing “embarrassment and error.” No “business of similar magnitude, and complication, when all the circumstances are taken into view,” Lumpkin bragged, “was ever in so short a period, systematized, partly settled, and brought into a form.” If a few million dollars would buy the elimination of native families, Lumpkin was happy to adjudicate claims in a spirit of justice. Property should be valued “in a spirit of liberality and justice,” he directed, avoiding “parsimony” on the one hand and “extravagance” on the other.8

He was less liberal with Cherokees who refused to cooperate. Lumpkin urged General Wool to put down any opposition by force, if necessary. In closing, he proclaimed bombastically that the Treaty of New Echota “will be executed, or it will be recorded ‘that Georgia was.’ ” When Wool reported that starving Cherokees refused to accept federal aid, Lumpkin was gratified. Only those willing to abandon their homelands should be fed, he insisted. “We would invite all who are ready to perish, to come and partake of this benevolent provision,” he and his fellow commissioner wrote. “Then if any suffer,” they continued, “it would be justly chargeable to their own obstinacy.” According to the moral calculation that satisfied Lumpkin, it seemed commendable to dispossess native families, feed the starving survivors who decided to move west, and blame those who did not for their own demise. (When planters punished enslaved people, they relied on a similar logic, blaming the victims when the planters themselves committed the original crime.) But even then, Lumpkin resented feeding the starving refugees. The goal of the commissioners, as Lumpkin saw their task, was “to carry off emigrants” as fast as they could be collected, but rather than hurrying off to the West, hungry Cherokees were “fattening on the bounty of the Government.” He consoled himself that, after the accounts were settled, Cherokees would be subject to “the imperative command” of the federal government: “To the West, march, march.”9

~~~

WHILE THE War Department tightened its grip on the Cherokee Nation, John Ross continued to wage a tireless campaign to undermine the Treaty of New Echota. Deportation had proven to be so explosive that it became one of the rallying points for northern politicians who were unhappy with the Jackson administration, and even some southern politicians began cautiously opposing the president’s Indian policy, if only to bolster their national ambitions. Ross hoped to outlast his longtime antagonist, who would leave office at the expiration of his second term on March 4, 1837. Jackson had been consistently hostile to native peoples from the start of his lengthy public career, even while professing a paternalistic devotion to them, the same fatherly concern, as the iron-fisted patriarch saw it, that defined his relationship with his slaves. He met some disobedient children with a whip in hand; others he confronted with armed militia.10

In public settings, native peoples occasionally professed to admire President Jackson. Like white Americans, they celebrated military prowess, and if they had not personally experienced his unsparing power, they knew of it by reputation. But it would be naive to take their expressions of respect at face value. The Chickasaws had questioned Jackson’s paternalism in 1830 when negotiating with him in Franklin, Tennessee, as had at different times the Senecas, Choctaws, and Creeks. The public rebukes, cautious as they were, reveal native skepticism about Jackson’s self-proclaimed benevolence. In private, what indigenous Americans said to each other is largely unknown, but a few extant letters hint at the depth of their hatred. John Ross noted that Jackson boasted “of never having told a red brother a lie, nor spoke to them with a forked tongue.” The Cherokee leader continued, “We have a right, however, to judge of this bravado for ourselves from his own acts.” No one was as forthright as the Cherokee John Ridge, who in a letter to a compatriot called President Jackson a “Chicken Snake” who hid in “the luxuriant grass of his nefarious hypocracy.” It was necessary to “cut down this Snake’s head,” he exhorted, “and throw it down in the dust.”11

While many of Jackson’s admirers and detractors alike commented on his strong-willed personality, one Cherokee delegation came away with a different impression of the president. Meeting with him in 1834, they asked whether he had decided to disregard the “binding obligations” of U.S.-Cherokee treaties. “He did not desire to answer,” one of the delegates reported. Rather than standing strong, Old Hickory “manifested a desire to equivocate” and “seemed to be afraid” to give a frank response. None of this surprised the Cherokees, who were “not ignorant of the true character of the white peoples chief.”12

For a time, Cherokees had hoped that Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s vice president and chosen successor, would lose the election of 1836, perhaps to Hugh Lawson White, a Tennessee senator who possessed a mawkish affection for native peoples. As the chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, White had introduced the expulsion bill in the Senate in 1830, but he later broke with the president, as did a number of other Tennessee politicians. In 1834, he had supported a resolution recommending that the federal government purchase land from Georgia on behalf of the Cherokee Nation, a proposal that embarrassed Jackson and encouraged Ross and his allies.13 Van Buren won the election, however, and in any case White would prove to be an unreliable ally.

Nonetheless, there were other avenues to pursue. Abolitionists, who were playing an increasingly vocal role in national politics, spoke loudly about the connection between plantation slavery and the deportation of native peoples. The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society stated in its annual report of 1838 that the “primary object of the South, through the instrumentality of the national government, is doubly atrocious.” First, planter-politicians wished to take “forceful possession” of native lands. Then they intended to establish slavery, “with all its woes and horrors,” on the stolen territory. The targets of this allegation saw no reason to debate the point, since they were proud of the empire of slave labor camps that they were building across the continent. The movement against expulsion, charged a slave-owning Tennessee congressman, was “nothing more nor less than a branch of Abolitionism in disguise.” Seeking converts in the South, one northern activist sent copies of the abolitionist newspaper Human Rights to the Cherokee Nation.14 Though John Ross and many other slaveholding Cherokees were themselves opposed to emancipation, any political division that split northern and southern politicians served their cause.

As late as November 1837, eighteen months after the Senate had ratified the Treaty of New Echota, Ross was still negotiating with the U.S. government for a permanent homeland in the South. He even rejected a preliminary offer from the United States that would have allowed Cherokees to remain in North Carolina and Tennessee in exchange for their Georgia and Alabama lands. The region was too small and mountainous, he said, holding out for a better agreement. If negotiations failed, he assured, Congress would still consider the matter “under circumstances more favorable, than at any other period heretofore.”15

Ross correctly anticipated a groundswell of opposition to the Treaty of New Echota in the northern states. Sherlock Gregory, an incessant advocate from upstate New York, asked Congress to annul his citizenship until the United States atoned for its treatment of Native Americans and abolished slavery. On a single day in December 1837, the implacable Gregory fired off five petitions demanding congressional investigations of the treatment of Native Americans. When he was not calling for the liberation of native and enslaved peoples, he was railing against women’s rights and Catholicism. Obviously, few people were as eclectic and vociferous as the impassioned Gregory. Still, thousands of Americans petitioned for the annulment of the treaty. Seventy women and men from Candor, New York, a rural area ten miles south of Ithaca, asserted that the treaty was “obtained by fraud.” The citizens of Portland, Maine, demanded that, in justice to the Cherokees and “in belief of a God who is the Avenger of the oppressed,” the United States should use “no means to compel the departure of said tribe.” Seventy-two women from Holliston, Massachusetts, thirty miles west of Boston, asked Congress to defend Cherokees “from the cupidity and from the illegal and cruel aggressions of our own countrymen.” Likewise, the citizens of Bristol, Connecticut, argued that enforcement of the treaty would be a “violation of principles of justice and of existing treaties” and “derogatory to the character of this confederated Republic,” exposing the United States to “the judgments of the God of nations.”16

In Union, New York, women and men observed that both Andrew Jackson and John Calhoun had made treaties with native nations. “Did they at that time, doubt the constitutionality of such engagements,” they asked, “or that the treaty was binding on the several states, or the general govt?” “If our national faith is abandoned,” they continued, “nothing of our vaunted republicanism worth contending for is left, and the days of our republic are numbered.” “We are aware that the policy of removing Indians is asserted to be out of friendship to them,” they wrote. “But is it friendship,” they asked, “to expel a people from their beloved country by the sword?” From all present appearances, they concluded, the plans being put in place were not “in pursuit of the welfare of the Indian.” Instead, federal policy obviously existed “to satisfy the craving of their white neighbours.”17

Petitions arrived from Warren, Connecticut; Brooklyn, New York; and Orange, New Jersey. The residents of Concord, Massachusetts, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, told Congress that the Treaty of New Echota was “an atrocious fraud” and “an outrage upon justice and humanity.” In the Senate, a weary clerk counted signatures and recorded the results on the back of each petition: 45, 106, 114, 164, 88, 146, 197, 55, 21, 108, 213, 245, 404, and so on.18 Nevertheless, the pushback from southern senators was considerable, so the protests were “laid upon the table,” precluding debate on the matter. Clearly, Ross had miscalculated.

The longest petition came from the Cherokee Nation itself and surpassed all others in urgency. The “cup of hope is dashed from our lips; our prospects are dark with horror; and our hearts are filled with bitterness,” it read. “Are we to be hunted through the mountains, like wild beasts, and our women, our children, our aged, our sick, to be dragged from their homes like culprits, and packed on board loathsome boats, for transportation to a sickly clime?” With 15,665 subscribers, the memorial, like a previous one from the Cherokees in 1836 that contained 14,910 names, was greeted with incredulity. Elias Boudinot, now residing with forces that viewed emigration as a necessity, had called the older petition a “fraud upon the world.” After all, he maintained, there were now only about fifteen thousand Cherokees still remaining in the East. Ross “over shot the mark,” charged John Schermerhorn, objecting that by his estimate there were only four thousand Cherokee men left in the region. To the Treaty Party that favored moving west, the petitions embodied Ross’s faults, for the principal chief was humoring a “delusion” by failing to be candid with his fellow Cherokees. Ross asked his constituents, “Do you love your land?” and “Do you wish the white people driven out of the country?” Of course, the answers were uniformly positive. Posed differently—“Will you choose to live in this miserable condition among whites?”—the responses might have been very different. Ross belonged to a group of “rich half breeds” who did not share the interests of the common people, charged two Cherokees, who ironically were themselves wealthy and of mixed ancestry.19

The picture of a tyrannical Ross appealed to planter-politicians, who saw the Cherokee leader as the mirror image of themselves. As Wilson Lumpkin wrote to the like-minded Jackson, the vast majority of Cherokees were akin to slaves, “too ignorant and depraved” to think for themselves and “incapable of self government.” They “should be treated as children.” Ross ruled over them “just as much as the slave is governed by the opinion of his master,” but while Lumpkin and his peers were benevolent fathers to their enslaved children, Ross, by comparison, was a tyrant to his. If only the Cherokees understood that Lumpkin, not Ross, had their best interests at heart, they would abandon their homes for the West. Of course, the logical conclusion to this exercise in arrogance and self-delusion was that U.S. planters should enslave native peoples for their own good, a determination reached by more than one southern apologist.20

Another white southerner saw Ross as the “slave, rather than the leader, of his nation,” borne along by the overwhelming sentiment in the Cherokee Nation against expulsion. Perhaps this contrasting assessment better reflected the nature of leadership in many indigenous societies, including Ross’s own. Though Ross had been elected as part of the Cherokee Nation’s transition to a constitutional government, his authority rested on traditional sources, including the matrilineal clan, and his power depended on his ability to persuade. One missionary, a longtime resident in the nation, described a man who, soon after setting out for the West, stopped, loaded a rifle, and shot himself. “How vain then the reports that Mr. Ross has been keeping the people back from the west,” the missionary wrote, “since it is so entirely beyond his power to make them willing to go.”21

~~~

BY EARLY 1838, of the South’s native residents, only the Cherokees and Seminoles remained in significant numbers. The United States had deported the Choctaws during the cholera times. A few years later, it had fought, defeated, and deported the Creeks. Then in late 1837, the Chickasaws moved west. From their Mississippi homelands, they traveled a relatively short distance compared with other native southerners, enjoyed decent health, and avoided government contractors by funding their own journey. For these reasons, they suffered far less than others.22

With Ross and the vast majority of Cherokees remaining firmly opposed to deportation, the United States began preparing to conduct the expulsion by force of arms. By early 1838, the Engineering Corps had staked out roads through the Cherokee Nation in anticipation of an invasion. The War Department was particularly concerned about the region lying within present-day western North Carolina. If the Cherokees fought back, this area would surely become their stronghold, for it was filled with precipitous mountains and narrow valleys and ideal for concealment. In places, the creeks were “choked with thickets,” wrote the topographical engineer William G. Williams, and mountain trails sometimes ascended too steeply for troop movements. The twenty-five-mile trail between Fort Lindsay and Fort Delany, in the present-day Nantahala National Forest, was “exceedingly rough,” climbing along “dangerous rocky precipices of tremendous height and overhung by steep rocks and mountains.” Other trails clung to mountainsides with no easy way down. “No descent could be obtained,” wrote Williams, “that would not be very long and very expensive.” Still others were hemmed in by high riverbanks and “might be easily annoyed at such points by ambuscades.” To allow for the disposition of troops and munitions in this treacherous mountainous region, it was essential, wrote Williams, to survey the lands. The data “in case of emergency” would “contribute greatly to a prompt suppression of the Evil.”23

The people who had cultivated Appalachia’s green valleys “from time immemorial,” the War Department learned from its topographical engineer, shared the common characteristics of “the Indian.” The Cherokee was “Grave in his intercourse with whites, good tempered or sullen according to the treatment he receives from them.” (Someone, perhaps from the War Department, later underlined this bit of useless information.) He was “Cunning and reserved” and “Poor, ignorant of economy, of time or money.” Indians preferred “the chase of deer or sheer idleness to more useful employment.” And they unsurprisingly favored their own language. In terms of appearance, the men were “athletic” and “supple,” with an upright carriage and “elastic step.” Though Cherokee men of fighting age perhaps numbered only four or five thousand, they were supported by an equal number of women, who were “inured to hardship” and “would yield great assistance in time of war.” After completing this brief anthropological excursion, Williams concluded, “Little more need be said of these People.”24

Despite the Cherokees’ determination to keep their homes in the “mountain fastnesses” of southern Appalachia, the United States did have one essential advantage. With the federal government’s quiet acquiescence, squatters, prospectors, and marauders had already reduced Cherokees to a “state of extreme poverty and privation.” The first object of any military strategy against them would therefore be to occupy the fertile valleys that remained under Cherokee control and to seize the grain and cattle—in short, to starve them out. Reduced to extreme want, Cherokees would flee into the mountains, predicted Williams. Hogs and cattle had already destroyed many of the roots and plants that might otherwise contribute to the Cherokees’ sustenance, and the refugees would therefore be forced to survive off the inner bark of the white oak. But, with this inadequate diet, they would be “shortly attended with disease.” In their “precarious” situation, they would be easily brought to terms.25 John Ross had been right. The government’s “secret design”—begun with the passage of the expulsion act and culminating with the planned invasion of the Cherokee Nation—was to make their lives “so wretched and intolerable” that they would abandon their homelands.

On April 6, the War Department ordered Winfield Scott to report to the Cherokee Nation to oversee military operations, authorizing him to call up as many as three thousand volunteer soldiers from surrounding states. An additional 1,500 soldiers would be transferred from the Florida war to bolster Scott’s command. (Most of the regulars, however, arrived too late to be of use.) In preparation for the operation, the army had already established twenty-three military posts in the Cherokee Nation, and the quartermaster had shipped ordnance from Mobile. Scott traveled immediately to Athens, Tennessee, where he began studying the local topography and making preparations for “an early vigorous system of operations” to deport Cherokees. Though local native people showed “the most inoffensive deportment,” according to army intelligence, they appeared unified in their determined stance. “The universal expression amongst them is ‘that they will make no resistance, but they must be forced away.’ ”26

~~~

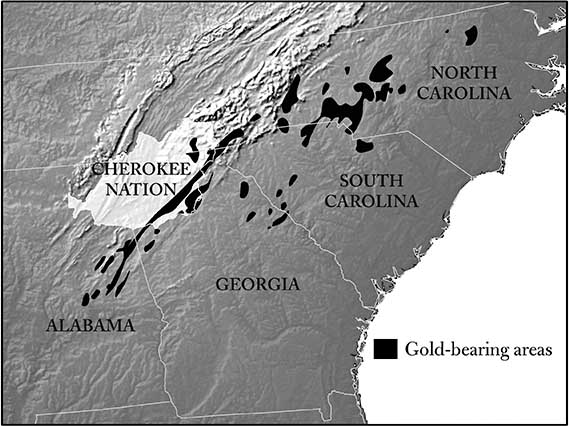

WHY DID U.S. politicians persist? By 1838, white southerners had already seized the most valuable indigenous lands, situated in the rich Black Prairie of Alabama and Mississippi. They could hardly have coveted the remote and mountainous Cherokee homeland in southern Appalachia for extensive cotton cultivation. The chance discovery of gold in Cherokee country in August 1829, it is true, attracted the interest of some of the most powerful men in the United States. The ubiquitous J.D. Beers bought a share in a mine just inside the southern border of the Cherokee Nation, and he acquired the output of surrounding mining operations as well. In the same neighborhood, John C. Calhoun also purchased an interest in a mine, using slave laborers to carry out the backbreaking work, as he did on his South Carolina cotton plantation one hundred miles to the east. George William Featherstonhaugh, the British-born geographer, toured north Georgia’s gold-laden mountains with Calhoun in the fall of 1835 and noted that the valleys were “all dug up.” In the mad rush to strike it rich, miners had uprooted centuries-old trees, rerouted mountain streams, and deposited tailings in large unsightly mounds. The once-verdant valleys of the Appalachian foothills, he said, were “a picture of perfect desolation.”27

And yet, by most accounts, gold mining peaked in the early 1830s, several years before the United States forced Cherokees to embark on the Trail of Tears. One scholar of the subject suggests that southern gold production, which was concentrated in Georgia and North Carolina, fell by 31 percent between 1834 and 1837. Those somewhat conjectural numbers err on the side of caution, and the decline may have been even greater. In 1838, one Georgia newspaper, hoping for a revival of the industry, admitted that the “high price of cotton, and consequently of labor, caused the Southern gold mines to be comparatively neglected for a few years.”28

Regardless of the exact numbers, the peak years of mining in the early 1830s had proven that Georgia’s citizens could exploit the gold deposits even while Cherokees remained on their homelands. In fact, most gold-bearing areas in the South did not lie within the Cherokee Nation, and most of the Cherokee Nation did not bear gold. As a result, large parts of the region did not interest colonizers. While thousands of fortunate drawers in the Georgia land lotteries had moved into the Cherokee Nation to seize their winnings, many others declined to claim their land, leading the legislature to extend the deadline to file paperwork every year until 1842. John Bell of Tennessee, the chairman of the House Committee on Indian Affairs, even suggested in May 1838 that his constituents would have acquiesced to the “permanent residence” of Cherokees on their “ancient possessions”—though he later underscored that events had since ruled out that possibility.29

Planter-politicians of course had other reasons besides cotton and gold to clear the South of native peoples, as Representative William Dawson of Georgia outlined in a fiery speech on the floor of the House in May 1838. President Van Buren’s secretary of war, Joel Poinsett, had recently proposed delaying Cherokee expulsion by two years, and congressmen who opposed U.S. Indian policy had temporarily stalled a bill to fund the Seminole war and Cherokee expulsion. As John Ross and a Cherokee delegation listened from the gallery, an outraged Dawson attacked his colleagues. The defenders of the Indians, he charged, were either ignorant or moved by “a prurient disposition to be esteemed the bold assailants of the supposed oppressors, and the vindicators of the oppressed.” The Georgia congressman accused northerners of hypocrisy. “Go and read the tale of your own Indian wars,” he goaded his northern colleagues.30

Gold-bearing areas in the South.

Dawson enumerated the reasons that the region’s longtime residents must be expelled. Cherokees were lawless. White mothers in Georgia could not visit their daughters in Tennessee without crossing through the Cherokee Nation and putting themselves at risk of being raped. Entrepreneurs could not build roads and bridges through the region. Drivers of horses, mules, and hogs were compelled to travel great distances to pass around the Cherokee Nation. And the state could not proceed with the “great work of uniting by railroad the western waters with the Atlantic.” All these inconveniences and injustices arose, he said, “because the Cherokees claimed the unrestricted right to the country.” If Georgia did not get its way, he threatened, it would secede. And if federal troops crossed into the state to “castigate” it, its citizens would meet them at the border with arms.31

As indignant as Dawson sounded, his reasons do not adequately account for the unshakable determination of Georgia’s planter-politicians to expel Cherokees from southern Appalachia or the unbounded fury they directed at everyone who challenged them. While they postured by standing on states’ rights, white supremacy in fact made up the bedrock of their politics. As the citizens of Walker County, Georgia, in the northwestern corner of the state, put it, the Cherokees “invite to action our internal as well as external enemies.” These stalwart defenders of white supremacy resolved that each citizen procure a firearm and fifty rounds of ammunition to meet the internal threat of a slave uprising and the external threat of a foreign invasion—and, when the time was right, to drive off the region’s oldest residents “at the point of a bayonet.”32

Perhaps some element of reason stoked the fears of Walker County’s citizens. Practically speaking, the Cherokee Nation was a competing sovereign entity in the heart of the South, governed by people who were manifestly opposed to the guiding ideology of the region’s white ruling class. In addition, its status as a “domestic dependent nation” created a special relationship with Washington City that invited federal power into the region. But Walker County was hardly a prime location for a slave rebellion. It had perhaps a thousand enslaved laborers who were outnumbered by a factor of ten to one.33 The likelihood of Cherokees teaming up with a foreign power was even more remote.

Something more powerful than reason motivated Walker County’s citizens. Thomas Jefferson, despite or because of his troubled relationship with enslaved African Americans, had put his finger on the source. Slavery, he said, turned planters into despots who were habituated to ruling but not being ruled. The habit extended to the South’s non-slaveholding whites as well, who were empowered by law to lord over “colored people.” The very existence of the Cherokee Nation insulted them. Representative George Washington Bonaparte Towns of Georgia, bearing the name of both a planter and a despot, warned Congress in May 1838 that his state would never be “castigated into submission” by being forced to recognize Cherokee rights. That was a punishment properly meted out “to the slave or the serf,” the congressman declared, not to a proud slaveholding state that jealously guarded “her honor and her liberty.”34 By asserting their “rights,” planter-politicians such as Dawson and Towns would bring to fruition the project they had launched in 1830. They would leave not a single indigenous person in the region, thereby making white men the masters of every square foot of the South. The expulsion of the Cherokees would realize the vision outlined in 1825 by Georgia’s “Socrates.” “We the people of Georgia” would become “we the white people of Georgia.” Untroubled by sovereign Native Americans, planters would reign unchallenged over their African American slaves.

As he listened from the House gallery, it is not known what John Ross made of Dawson’s ill-tempered speech, or whether he was on hand the next day to witness the fistfight that broke out between John Bell and a Tennessee colleague during the continuing debate over the Indian funding bill. On June 5, still in Washington City, a resigned Ross wrote, “The removal of the Cherokees from their native land, right or wrong, appears to be the fixed and unalterable determination of this government; it remains now only for the United States to promulgate the decree.”35 Ross was unaware that ten days earlier Winfield Scott had already launched the operation to deport the Cherokees from their eastern homelands.

~~~

THE CHEROKEE expulsion began on Saturday morning, May 26, 1838, eight years to the day after the House of Representatives had passed the “Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians” by a five-vote margin and turned the deportation of eighty thousand people into federal policy. General Scott’s orders to his troops were clear. He commanded his men to surround and arrest “as many Indians” as possible, leave them under guard in the nearest fort, and return for more. “These operations will be again and again repeated,” he directed, until every indigenous person was imprisoned.36

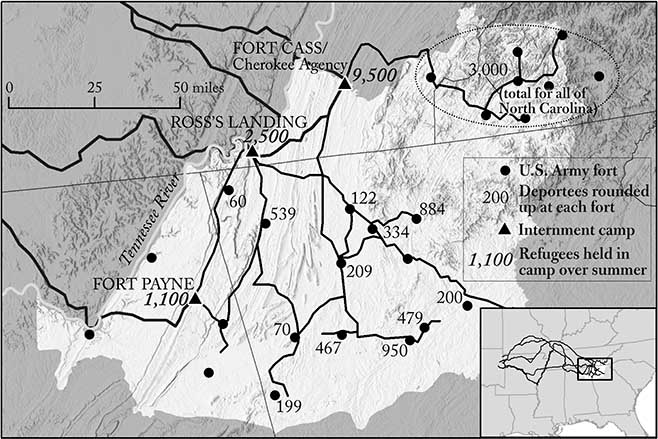

The massive buildup of troops was large enough “to broil, pepper and eat the Cherokees,” bragged the commander of the Georgia militia. With 3,500 soldiers, General Scott could field one soldier for every four deportees, a force “so large and so overwhelming,” wrote one general, that resistance would be “hopeless.” Sheer numbers seemed to ensure that the dispossession would unfold at lightning speed. Though state militia were undisciplined and often drunk, they swept over mountains and scoured river valleys, “taking Indians” through the day and leaving no time for the dispossessed to collect their belongings or even to gather their children. At night, they roused families from their homes, placed them under guard, and then slept in their still-warm beds. The next day, they continued the search from house to house, eventually marching the prisoners at bayonet-point to regional forts, where hundreds of people awaited transfer to one of the three central internment camps, Fort Payne in Alabama and the two larger military outposts in Tennessee, Ross’s Landing and Fort Cass. It was fatiguing work, complained one volunteer, and not “what it was cracked up to be.”37

Most Cherokees complied with the soldiers’ orders, determined not to provoke armed men who, in the words of one general, thought it “no crime to kill an Indian.” However, scores of people, especially from North Carolina’s Cheoah Valley, in the extreme southwestern corner of the state, fled into the mountains when the troops arrived. “A more religious people than inhabits this valley cannot be found any where,” wrote an admiring soldier. “Their preachers speak of the prospect of their speedy removal,” he continued, “and the subject never fails to throw the congregation into Tears.” Despite the War Department’s careful preparations to move munitions and soldiers through North Carolina’s alpine terrain, its officers could not capture the Cherokees. The fugitives formed the nucleus of what would become the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, recognized by the federal government as a distinct Indian nation in 1868.38

The terror that the soldiers spread as they moved through the nation can only be glimpsed through fragmentary records. They seized individuals who were engaged in the routine tasks of daily life, visiting friends, tending to livestock, and farming. They shot dead a deaf and dumb man, who tried to flee at the sight of the armed intruders. They drove two hundred children, women, and men through torrential rain, with scarcely a blanket to protect them. One soldier leveled a gun at a father and ordered him to board a barge, though the man had asked to wait for his young son. Infants and the aged especially suffered, since they were more susceptible to dysentery and to the effects of exposure. Soldiers forced one elderly woman, said to be nearly one hundred years old, to march all day and night to the point of exhaustion. They were suspected of killing another, who was unable to continue walking, and of hiding the body off the road.39

Military forts and internment camps May–December, 1838. The number of deportees, where given, is approximate.

In mid-June, only a few weeks after the launch of the operation, the commander of the Georgia militia reported that the operation was complete. Scouts had recently searched north Georgia “in every direction, without seeing any Indians, or late Indian signs,” but to be certain, mounted volunteers swept the country once more. The land was deserted. “Georgia has been entirely cleared of red population,” announced General Scott a week later. The residents, numbering nearly fifteen thousand, had been herded into camps across the border in Tennessee and Alabama, where they awaited deportation. Many were “ragged and miserable,” prompting the federal government to purchase clothing for them for the march west. The refugees rejected the false charity, stating that they had clothes of their own, which they had not been allowed to bring.40

Throughout the region, houses stood empty of residents and the objects of everyday life rested in place: a fiddle, chairs, a bed, a spinning wheel, a cooking pot, a bag of dried fruit, a playing horn. But this eerie absence of people was only temporary. Troops stole much of the Cherokees’ property, and “work hands” followed soon after to collect what remained for auction by the federal government. John Dawson bought four axes that belonged to Teliska, tools that the planter probably turned over to his nine slaves. Mr. Sloan purchased Chewey’s fiddle, Mr. McSpadden bought Crabgrass’s canoe, John Oxford purchased Amateeska’s pot, and Miss Godard bought Sopes’s bed.41 U.S. citizens moved into Cherokee houses, slept in their beds, and ate out of their pots. The occupiers used sheep shears, hoes, and fishing spears, augers, baskets, and fiddles that still bore the handprints of the original owners. The arrogation of Cherokee things, as bizarre as it was, went without comment in the southern press.

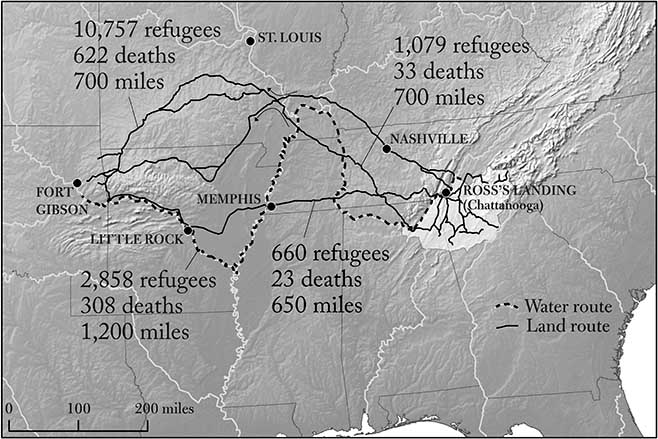

That June, the U.S. Army deported nearly three thousand people by steamboat. Taking the same route as Joseph Harris’s detachment a year earlier, the transports followed the Tennessee River to the Ohio and Mississippi. Traveling down the Mississippi, they reached the Arkansas and ascended that river nearly to Fort Gibson. Mortality on the crowded and disease-ridden steamboats surpassed 10 percent during these summer deportations. As the water fell in western rivers and made steamboat travel unreliable, Cherokees arranged with the army to remain in internment camps in the East until the fall. When the cool weather arrived, Cherokees promised to transport themselves rather than depend on erratic and dishonest government contractors. At least 353 people died in the crowded and unsanitary camps during the hot southern summer.42

The majority of Cherokees, weakened after spending four months in camp under armed guard, set out for the West in October and November 1838. Nearly eleven thousand people in eleven separate detachments traveled northwest through Nashville, Tennessee, passing ten miles west of the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s thousand-acre plantation, where the retired president commanded more than one hundred slave laborers. Continuing northwest, they crossed the frozen Ohio and then bore west through the southern end of Illinois. They crossed the Mississippi at Cape Girardeau and followed two slightly different routes through Missouri. One hundred miles from their destination, they turned nearly due south, before bearing west and crossing into present-day Oklahoma. The arduous seven-hundred-mile trek through mud, rain, and ice took four months to complete entirely on foot. Extrapolating from incomplete data, it appears that approximately 6 percent, or more than six hundred, of the nearly eleven thousand refugees who followed this northern route died during the journey.43 Smaller numbers went by water or followed slightly more direct overland routes. But even the 660 deportees who took the shortest overland route, walking nearly due west through Tennessee and Arkansas, still covered 650 miles by foot.

Including the military’s June deportations by steamboat and the Cherokee-led overland treks in the fall, approximately 1,000 people died directly during the months-long operation, representing nearly 7 percent of the population. A different accounting, which incorporates deaths in the holding camps as well as miscarriages, infertility, and other causes of reduced birth rate, produces a toll more than three times as large, at 3,500. The numbers do not capture the suffering. Three fatalities, horrendous but no different from hundreds of others, include an infant who succumbed from dysentery, a woman who was crushed by an overturned cart, and an elderly man, chilled to the bone, who dozed off too close to a campfire and burned to death.44

George Hicks, a friend of John Ross’s, led one of the last detachments of Cherokees to leave their homeland. “It is with sorrow that we are forced by the authority of the white man to quit the scenes of our childhood,” he wrote, describing how U.S. citizens robbed them in plain daylight as the massive caravan of 1,031 refugees, sixty wagons, six hundred horses, and forty pairs of oxen departed the Cherokee Nation. The long winter trek on the northern route took over four months, and seventy-nine people died along the way. When the survivors finally arrived in the West, the federal agent received them with rations of corn and beef that were unfit for human consumption. From “the promises made to us in the Nation East,” Hicks jeered, “we did not Expect such Treatment.” 45

The “Trail of Tears,” showing the routes that Cherokees traveled from their eastern homeland in the summer and fall of 1838. In some instances, I have extrapolated the number of deaths from the mortality rates of detachments that traveled the same route.