CHAPTER 3

THE DEBATE

~~~

IN THE 1830s, it seemed that every crossroads in the United States printed its own newspaper. Hundreds of small but boosterish towns such as Erie, Alabama, Flemingsburg, Kentucky, and Limerick, Maine, supported one and sometimes two papers. Across the nation, approximately 1,300 newspapers served nearly thirteen million people, making one newspaper for every 10,000 Americans, including the 16 percent of the population who were enslaved and by force of law not permitted to learn to read. In this sea of newsprint, self-proclaimed experts, some of whom had never before met a native person, expounded endlessly on “the Indian question.” The question was “one of deep concern,” commented the Massachusetts Salem Gazette. It inspired “flights of fancy, touches of pathos, and streams of eloquence,” mocked the Delaware Gazette and State Journal. The Savannah Georgian, confident that the white people of its home state would carry the day, smirked at the “tea-pot tempest” stirred by “the Indian question.”1

In indigenous communities, an equally lively but more informed discussion took place at the same time. Unfolding in council meetings, churches, and homes, most of it never appeared in print, and only occasionally did native peoples commit their thoughts to paper, usually with the assistance of a translator and scribe. Fortunately, the Cherokees launched their own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, in 1828. Published in the Cherokee capital of New Echota in what is now north Georgia, many of its articles appeared in both English and Cherokee, using the script invented in the second decade of the nineteenth century by Sequoyah, a Cherokee polymath from the Little Tennessee Valley. In Sequoyah’s original hand-drawn script, the syllabary consists of eighty-six ornate characters, each one representing a syllable in the Cherokee language; in print, the characters, reduced to eighty-five, are blockier and, in a few instances, resemble uppercase letters from the Roman alphabet. Within a few years of Sequoyah’s “transcendant invention,” as John Ross called it, an estimated ninety percent of Cherokees were literate. For the first time, they could disseminate print in their own language and use the New Echota press to discuss, debate, and mobilize during the pivotal era of expulsion.2

In December 1829, the Cherokee Phoenix printed a “Memorial of the Cherokees” to the U.S. Congress, rendering the petition in both Cherokee and English. (Though the Cherokee version appears first on the page, it is not clear which is the original language.) “You are great and renowned,” the memorial stated in English; “we are poor in life, and have not the arm and power of the rich.” As in this instance, indigenous orators often made themselves out to be supplicants to a more powerful party. The strategy resonated in native communities, since indigenous people were known for their extraordinary generosity, especially compared with the measured compassion of white Americans. “Will you have pity upon us?” the memorial asked.3

After establishing the relationship between benefactor and beneficiary, the memorial pivoted to dispute Georgia’s assertion that the Cherokees were mere “tenants at will.” The state’s aggressive actions violated Cherokee treaties with the United States, it stated, and flouted the intercourse law of 1802, which stipulated that indigenous lands could only be conveyed by federal treaty, not by private or state contracts. Unconstitutional and illegal, dispossession would also be “in the highest degree oppressive.” “From the people of these United States, who, perhaps, of all men under heaven, are the most religious and free,” the English-language memorial concluded, “it cannot be expected.”

The Cherokee version differed in significant ways, reflecting the desire of Cherokee politicians to appeal to both the American public and the Cherokee people. In English, the memorial praised “civilized life” and the “christian religion,” words dear to the hearts of northern reformers but of less purchase in the Cherokee Nation. In Cherokee, instead of civilization and Christianity, the memorial spoke of “learning,” “knowledge of the written word,” and acceptance of the “word of God” or “Creator.” The English version affirmed the stereotypes held by U.S. politicians, characterizing Cherokees as having been “ignorant and savage.” The Cherokee version, by contrast, said simply that they had been hunters. In English, the memorial gently told Congress, “We now make known to you our grievances,” while in Cherokee, it protested, “Your people have treated me (us) bad,” flatly asserting that U.S. citizens had “cheated” the Cherokees. Perhaps most revealingly, after describing the fate of indigenous peoples in the North, the memorial asked Congress in English, “Shall we, who are remnants, share the same fate?” In Cherokee, this supplication became an accusation: “And still you have no compassion for us—Your intention is to just drive us towards the west, brother.”4

At the time of the memorial, the Cherokee Nation, significantly reduced from its former extent, stretched from the outer limits of present-day metro Atlanta a hundred miles north to the southern boundary of the Great Smoky Mountains and from western Alabama two hundred miles northeast nearly to Franklin, North Carolina, covering a region of rolling hills, steep mountains, and wide valleys. Messengers carried the memorial from town to town, where local leaders read the Cherokee version in council and, with approval, recorded the names of male residents. “For want of time,” according to the Cherokee Phoenix, not every person in the nation of roughly eighteen thousand could sign the petition, but the document traveled widely enough to gain over three thousand names, most of them written in the Cherokee syllabary. Cherokee women do not appear among the memorialists. They had spoken against land cessions in the past, if only rarely, since diplomacy was traditionally the realm of men. Their absence on this occasion may reflect the influence of the federal government’s civilizing plan. In fact, the 1827 Cherokee constitution borrowed heavily from its U.S. counterpart, and it reflected state laws across the Republic by prohibiting women from voting in national elections.5

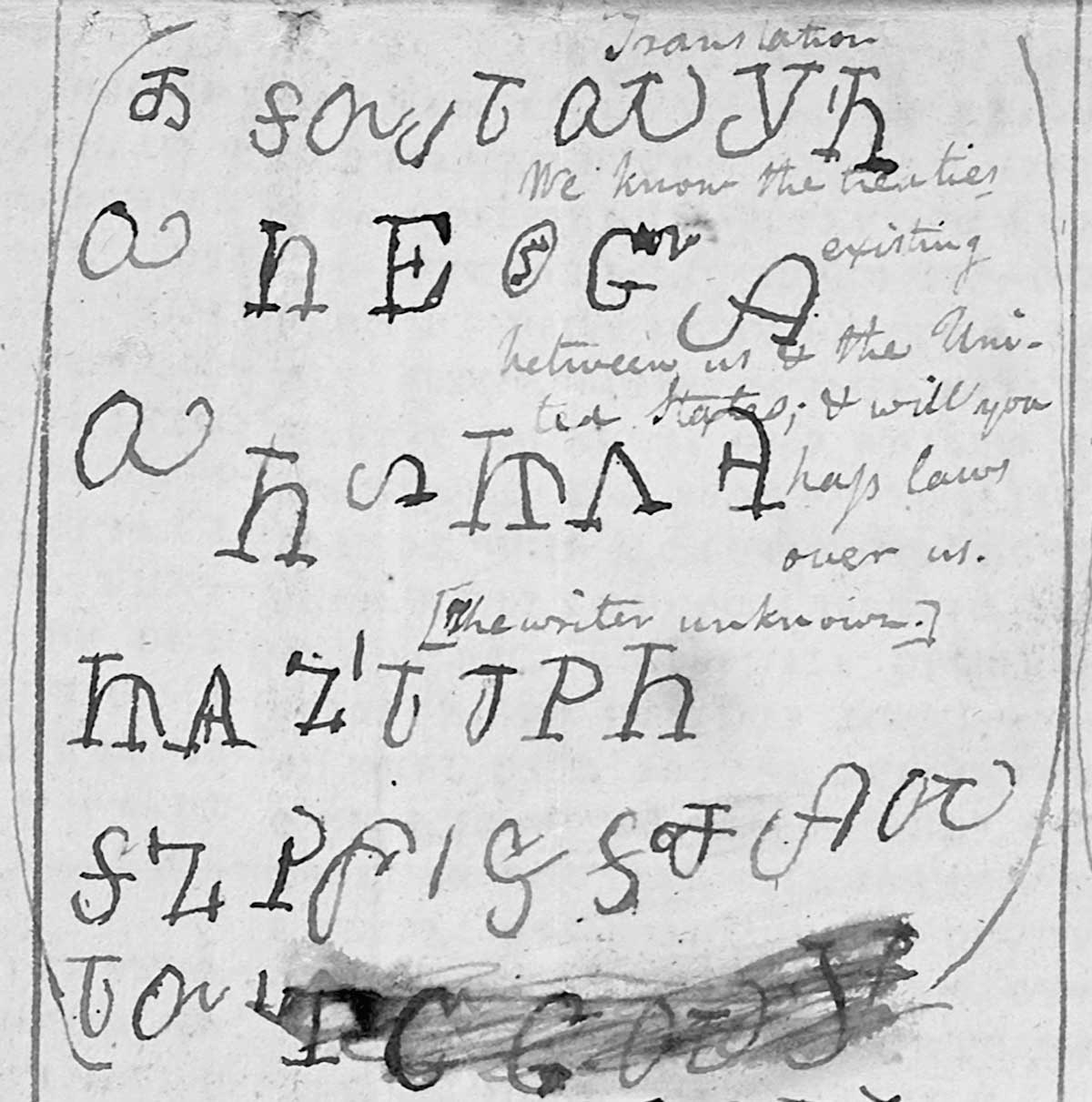

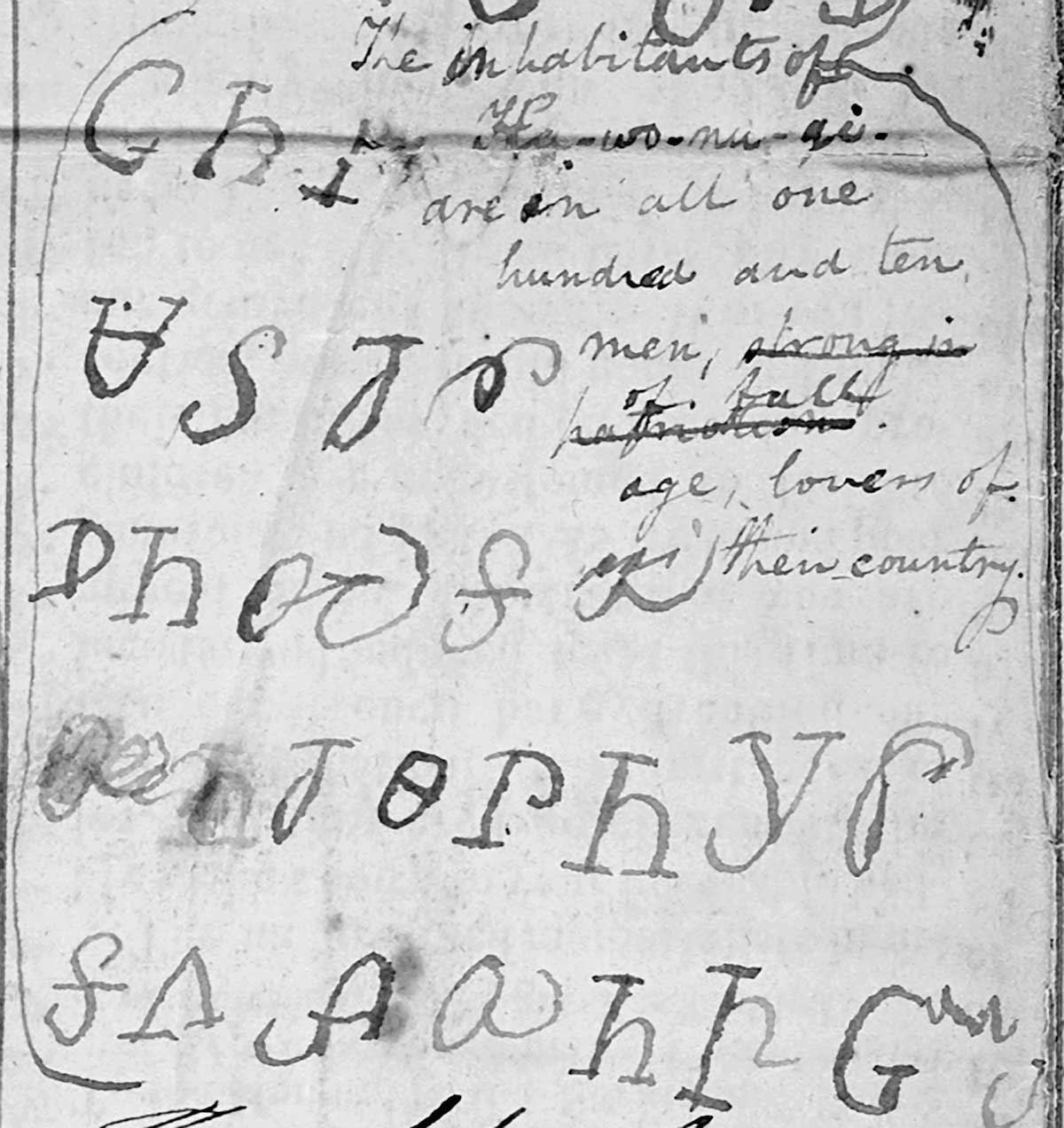

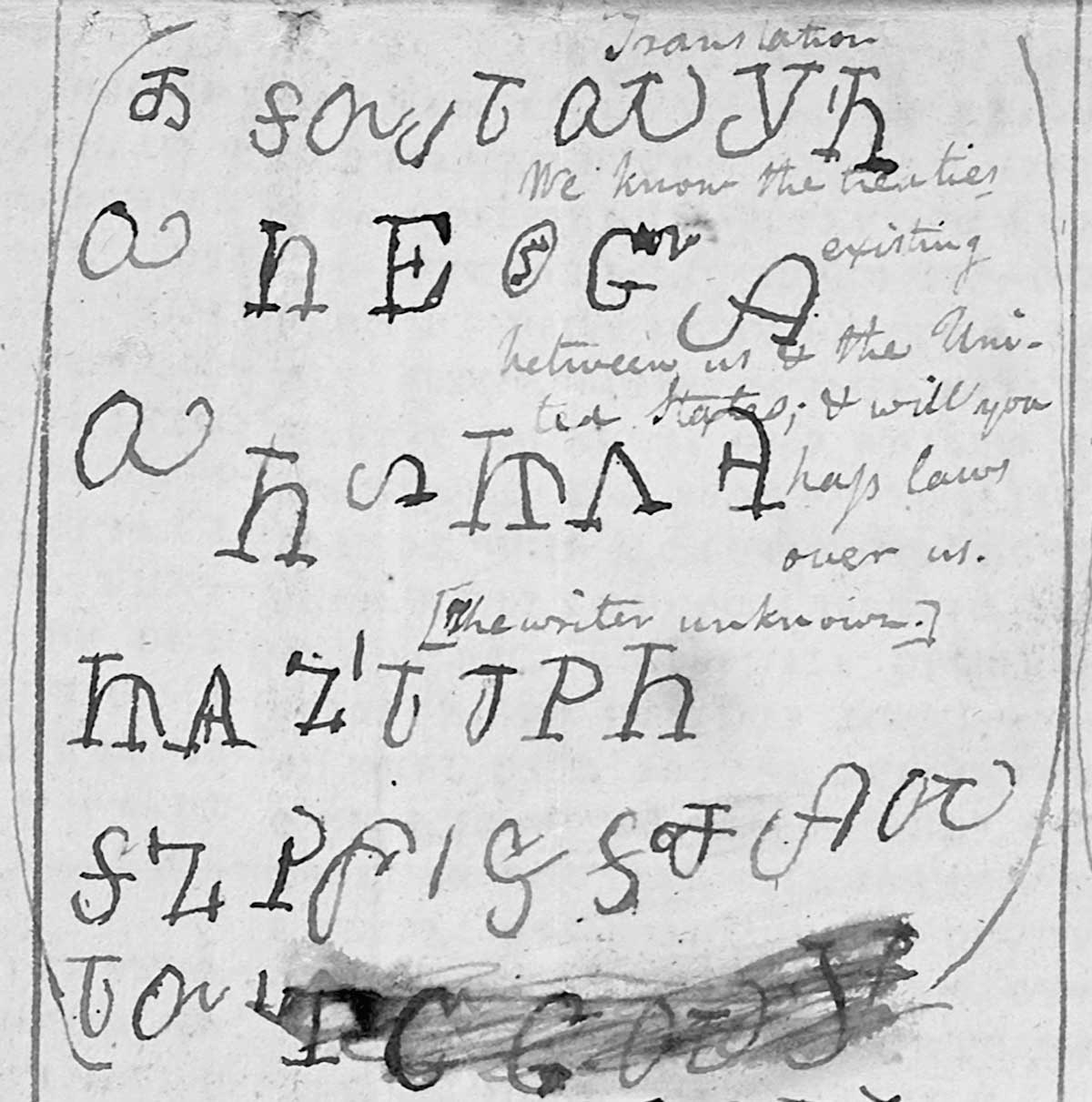

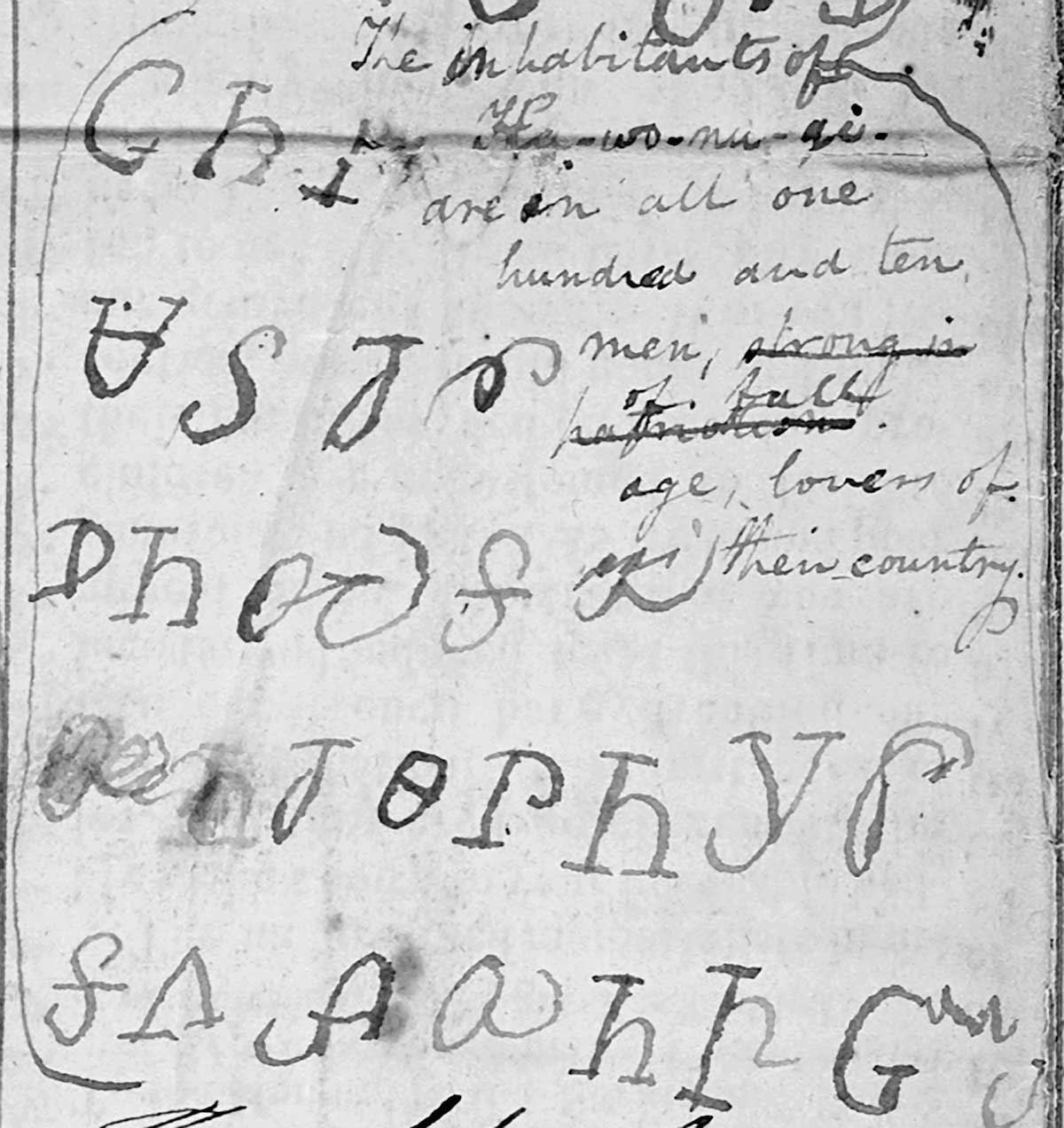

The bilingual memorial is a striking example of political activism. Even more illuminating are the individual expressions of resolve that memorialists added to the document. One anonymous Cherokee challenged U.S. agents to justify their actions in light of U.S.-Cherokee treaties: “ .” The expression literally means, “We know what the leaders said, or are they going to cover up that we met?” To clarify the expression for Congress, Cherokees paraphrased it as, “We know the treaties existing between us and the United States, and will you pass laws over us?” Another memorialist wrote, “

.” The expression literally means, “We know what the leaders said, or are they going to cover up that we met?” To clarify the expression for Congress, Cherokees paraphrased it as, “We know the treaties existing between us and the United States, and will you pass laws over us?” Another memorialist wrote, “ ,” meaning “People who live in Kawonugi all of the 1,100 strong men[,] the land they love it.” The phrase “the land they love it,” which appeared more than once among the signatures, had a particular resonance in the Cherokee Nation, for it signaled a decisive rejection of further land cessions—exactly what white southerners feared most.6

,” meaning “People who live in Kawonugi all of the 1,100 strong men[,] the land they love it.” The phrase “the land they love it,” which appeared more than once among the signatures, had a particular resonance in the Cherokee Nation, for it signaled a decisive rejection of further land cessions—exactly what white southerners feared most.6

With Cherokee assistance, Creek leaders drafted their own English-language memorial to the U.S. Congress around the same time, but without a writing system, they could not circulate it widely to their people. The Creeks quoted a number of treaty articles in their favor, including the first Creek-U.S. treaty, signed by George Washington in 1790. They laid bare the hypocrisy of the South’s planter-politicians, who, with the help of Isaac McCoy, disguised their plans for mass expulsion as a form of benevolence. “Compulsion in its hideous feathers of inhumanity is not avowed,” they observed, “but is indirectly exerted to eject us from the repose and firesides we enjoy in a country to which we have the best of titles, by provision and solemn guarantees of the United States.” Alabama, they charged, was fattening “on the ruins of our natural and civil rights.” The question, they concluded, was not what was in Alabama’s interests or what the Creeks ought to do—a subject that paternalistic whites never tired of expounding on—but what was required by Creek-U.S. treaties.7

Written by one of the subscribers to the Cherokee memorial, the sentence literally means, “We know what the leaders said, or are they going to cover up that we met?” or, as translated at the time, “We know the treaties existing between us and the United States; and will you pass laws over us.”

Another subscriber to the Cherokee memorial wrote, “People who live in Kawonugi all of the 1,100 strong men[,] the land they love it,” or as translated at the time, “The inhabitants of Ha-wo-nu-gi are in all one hundred and ten men, strong in patriotism of full age, lovers of their country.”

The Speaker of the House, Andrew Stevenson of Richmond, Virginia, dismissed both petitions without discussion, laying them on the table on February 8, 1830. Though disregarded by Congress, the documents served a strategic purpose by rallying northern reformers to the cause. The Cherokee memorial was especially effective. First appearing in the Cherokee Phoenix, it was reprinted in newspapers throughout the northern and western states, one of many instances in which the New Echota weekly served as an essential weapon in the fight against deportation. The very existence of the newspaper refuted the rhetoric of savagery and dissipation that, it was said, made expulsion so urgent. One of the nation’s leading scientists and most ardent racists, Charles Caldwell, dismissed the ingenious invention of the syllabary as “virtually . . . a Caucasian production.” Sequoyah, Caldwell maintained, had “much Caucasian blood in his veins” and was inspired by the alphabet.8 But the newspaper was undeniably impressive.

On receiving a copy of the first issue of February 21, 1828, the Commercial Advertiser of New York observed, “A single sight of such a production is sufficient to overthrow a thousand times all the unprincipled declamation, and unfounded declarations, made by interested white men against the incompetency of all Indians for civilized life.” Even Georgia’s Augusta Chronicle had to admit that it was “handsomely printed.” In February 1829, Elias Boudinot, the newspaper’s talented editor, lengthened the name to the Cherokee Phoenix and Indians’ Advocate to reflect its expanded role in speaking for all native peoples against the federal government’s policies. Federal officers took note. The superintendent of Indian Affairs, Thomas McKenney, requested a complete run of the publication since its launch, as well as two copies of every future edition.9

The Cherokee Phoenix defied white southerners who believed that “persons of colour” should not speak for themselves, a conviction that preoccupied the Georgia Assembly and gave rise to several measures, ranging from the ludicrous to the lethal. In 1825, when Creeks insisted that the Treaty of Indian Springs was fraudulent, George Troup commissioned a history of the Creek Nation to prove them wrong “by evidence derived from . . . authentic sources”—in effect writing their history for them. A few years later, in December 1829, the Georgia Assembly was roused to action by the appearance in Savannah of sixty copies of an Appeal in Four Articles together with a Preamble to the Colored Citizens of the World, written by David Walker, an African American abolitionist born in North Carolina and living in Boston. One glance at the title, which referred to “colored citizens” and not people, prompted the police to notify the mayor, who in turn informed the governor. In a special session, the state legislature passed an act designed to prevent sailors who were “persons of colour” (exempting “any free American Indian”) from “communicating with the coloured people of this State.” Anyone circulating written materials that encouraged “insurrection, conspiracy or resistance” would be put to death under the new law. A second act that was passed that same day levied fines on printers who employed slaves or free people of color as typesetters. Alert to the dangers posed by “coloured people” who spoke for themselves, John Berrien, the Georgia-born Princetonian who was now Andrew Jackson’s attorney general, advised the president to ship the printing press and typefaces of the Cherokee Phoenix across the Mississippi. “I cannot too strongly urge its importance,” he wrote.10

Well before Boudinot’s Cherokee Phoenix arose, native peoples had found other ways to reach the American public. A twenty-two-year-old Cherokee scholar named David Brown interrupted his study of Hebrew, Greek, and French at Andover Theological Seminary in 1823 to embark on a speaking tour down the East Coast on behalf of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a New England–based organization dedicated to proselytization. Brown had become an accomplished orator addressing audiences in Salem, Boston, Cambridge, and Newton; now he was impressing overflow crowds as far south as Petersburg, Virginia. The tour was meant to raise money for the American Board, but Brown also used it to cultivate support for indigenous nations and to condemn colonization. It would have been better “had the natives never seen even the shadow of a white man,” he told an audience in Boston, citing, among other events, Jackson’s slaughter of the Creeks in 1813–14. In subsequent years, his letters appeared occasionally in the press. “How would the Georgians receive a proposition from the Cherokees to exchange the land they now hold, (which originally belonged to the Cherokees) for a tract of country near the Rocky Mountains?” he asked in 1825 in one widely reprinted missive. “Unless force is resorted to, unless the gigantic U. States should fall, sword in hand, upon the innocent babe of the Cherokee Nation,” he continued, “the Indian title to this land will remain so long as the sun and moon endure.”11

There were other speakers too: Elias Boudinot, the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix; John Ridge, Boudinot’s Cherokee classmate at Cornwall Academy in Connecticut; Red Jacket, the Seneca leader; David Cusick, the Tuscarora historian; and William Apess, the brilliant Pequot Methodist minister. Their advocacy ranged from the cautious to the confrontational, from recounting heartening stories of uplift to laying out damning charges against the United States. Among these political activists, no one was more perceptive and incisive than Apess. His 1829 autobiography, the first by a Native American, recounted a childhood of terrible physical abuse and deprivation, partially caused, he said, by white Americans, who robbed his people of their lands and gave them nothing in return but alcohol. “I believe that there are many good people in the United States, who would not trample upon the rights of the poor,” he wrote, “but there are many others who are willing to roll in their coaches upon the tears and blood of the poor and unoffending natives—who are ready at all times to speculate on the indians and cheat them out of their rightful possessions.” In a lengthy appendix, he singled out historians for vindicating the colonial conquest and newspaper editors for circulating “every exagerated [sic] account of ‘Indian cruelty.’ ” Apess’s self-published autobiography gave a voice to native peoples. In the 1830s, he would speak against the Republic’s triumphant national history and expose the contradiction between American values and American treatment of “colored people.”12

It was more difficult for women to play a public role in the fight over deportation, given the belief in the United States at the time that politics belonged to men. Unable to embark on speaking tours, native women had long made their concerns known in local council meetings, and in one extraordinary case in 1818, in a letter to the federal government. “Our neighboring white people seem to aim at our destruction,” wrote the author Peggy Scott Vann Crutchfield, a bilingual Cherokee, who pleaded that without federal protection “we are undone.” By the 1820s, however, women’s voices were increasingly mediated by Protestant missionaries. Nonetheless, their stories of uplift, told in letters and memoirs, countered the fatalistic narratives disseminated by southern politicians and inspired white women to launch a national petition campaign of their own against deportation.13

Native memoirs, letters, and speeches circulated widely in newspapers from Maine to Washington City, but rarely farther south, where many of them were written. Just as white southerners did not care to read the words of African Americans who had escaped from slavery, they did not want to hear indigenous peoples speak for themselves. The reason was clear. Like enslaved African Americans, Native Americans gave compelling testimony about their own oppression. Without their activism, there would have been no debate over expulsion. When the first bill “for the exchange of lands” was introduced to Congress in January 1830, native peoples had already cultivated a fervent opposition.

~~~

WITHIN WEEKS of Jackson’s inauguration, his administration began laying the groundwork for what would be the president’s signature piece of legislation. After the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions refused to support Jackson’s proposal, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Thomas McKenney launched the New York Indian Board for the Emigration, Preservation, and Improvement of the Aborigines of America in July 1829. It was a false-front organization, appearing to be a private initiative but funded by the federal government. The northern headquarters and the inspiring name wrapped slave owners’ favorite policy in gauzy humanitarianism. “This sort of machinery,” McKenney boasted, “can move the world.” It would “silence all opposers.”14

Isaac McCoy, however, correctly surmised that the organization would amount to no more than “a bag-of-wind.” Six months after its creation, the board voted to disband for lack of interest—few northern reformers were willing to lend their names to the charade—though not before Lewis Cass, Isaac McCoy’s old correspondent, published a widely read essay endorsing its goals. Cass, who would soon become Jackson’s secretary of war, was a former New England schoolteacher who made a political career out of supporting southern planters. His sixty-three-page essay was a morass of distortion and empty speculation. Native peoples were depressed by American “superiority,” improvident, habitually indolent, “implacable in their resentments,” fatalistic, and “an anomaly upon the face of the earth.” It was a wonder that they existed at all. Cass cited the Scottish historian William Robertson and the Swiss lawyer Emerich Vattel but relied mainly on two American authorities, McKenney and “the pious and laborious” Isaac McCoy.15

The essay caused a furor, eliciting a number of responses, none more scathing than the lampoon that appeared in Maine’s Bangor Register. Four years earlier, Cass had published an essay in the same North American Review that, his opponents asserted, contradicted his recent effort. In the first essay, he had heaped scorn on native peoples but confessed to being “apprehensive” that the proposal to expel indigenous Americans, “this gigantic plan of public charity,” would “exasperate the evils” that white Americans were “anxious to allay.” It was “better to do nothing,” he had concluded, “than to hazard the risk of increasing their misery.”16

Now Cass said the opposite. No matter, said the Register. “A great many very respectable men are obliged to wind up their opinions every eight days, as they wind up a clock.” If an ordinary citizen was entitled to oscillate, so much more was “his Excellency the Governor of Michigan Territory.” “If it shows any talent to think well upon one side of a question,” the newspaper mocked, “it must be allowed to show just twice as much to think well on both sides.” Cass held that the sovereignty of a nation was “to be judged of by the whites,” the Register observed, and that Indian sovereignty, if permissible, was “only allowable during good behavior.” Treaties, in Cass’s view, were not binding because Indians were savage, but the evidence of savagery, in the Register’s ungenerous summary, was absurd: The Scottish historian Robertson, who never set foot in North America, said that Indians ate bear meat and had no notions of property; the Swiss lawyer Vattel stated that farming, “a decent practice,” ought to be encouraged, and therefore Indians “ought to be exterminated”; and Spain and France treated Indians far worse than the United States. It was a caricature of Cass’s argument, to be sure, yet not so far from his actual polemic. The Register’s editor, Samuel Call, was said to be “a cynical gentleman of considerable sharpness of intellect,” but one wonders if some of the sharpness in this instance came from Maine’s Penobscot people. Call knew them from his time as a sympathetic state Indian agent in 1824.17

Among U.S. citizens, the Jackson administration’s most tireless foe was Jeremiah Evarts, the corresponding secretary of the American Board. Evarts was a Yale graduate and former lawyer who had found his calling as a social reformer. Though he had once favored the voluntary removal of indigenous peoples, Native American activists had turned him against the campaign to eliminate nonwhites from the United States. (The famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison had experienced a similar conversion at the hands of African American activists, who opened his eyes to the racism behind the American Colonization Society.) Under the name of William Penn, Evarts published twenty-four essays in late 1829 laying out the case against expulsion. The essays extended arguments that Native Americans had been making all along, which is perhaps not a surprise, since Evarts knew David Brown and Elias Boudinot and had traveled through the native South several times. Following the lead of indigenous activists, Evarts wrote about “solemn” treaties, the obligations imposed by the Declaration of Independence, and the improving prospects of Cherokees and other Native Americans, though he did so at greater length and to a larger audience. According to one contemporary, the essays appeared in at least forty newspapers and were read by a half million people in a country of thirteen million.18

With Evarts’s encouragement, antiremoval petitions began to flood into Congress. They arrived from New York City; Brunswick, Maine; Topsfield, Massachusetts (“I am authorized to state that every individual in this town is in favour of this memorial”); Pittsburgh and Philadelphia; Windham, Connecticut; Champaign, Ohio; and everywhere in between—but not a single one came from any of the slave states. Some were printed, others written in longhand. Signatures ranged in number from two or three to several hundred. One was seven feet long, another fifteen pages. Apologizing for the twenty signatures on his petition, J. Boynton of Philipsburg, New Hampshire, added a handwritten note to his senator: “In consequence of the bad state of travelling there has been but little opportunity of presenting this memorial to the inhabitants of this town, and I feel unwilling to delay longer to forward it.” The Senate Committee on Indian Affairs asked to be relieved of the burdensome duty of considering the petitions; it had already made known its firm desire to expel native peoples. A House member from Georgia asserted that the several thousand petitioners “were nothing in comparison with the millions who were silent and satisfied.” Compared with “contented majorities,” said another, “weak minorities always make the most noise.”19

The petitions, composed in the evangelical language of northern churches, are predictably parochial and reflect the unquestioned conviction that all the world should be Christian. And yet, drawing in part on the discourse of indigenous activists, the petitions are also deeply radical. It would be “childish” to assert that “the charters of European monarchs or the compacts of neighbouring states with each other can, by imaginary limits, or by lines of latitude and longitude, divest the original inhabitants of their lands,” wrote petitioners from New York City. White Americans were “invaders,” said residents in Pennsylvania. Petitioners from Brunswick, Maine, insisted that indigenous peoples had a “perfect right, by possession from time immemorial,” to their lands. Would the United States “trample . . . treaties in the dust” and sacrifice them “to avarice or ungodly ambition?” asked the residents of North Yarmouth, Maine. “We trust in God,” they continued, “that the United States will not fly to reasons of state.”20 The United States would do what was right, the Mainers hoped, rather than what was merely expedient.

One recurring theme in the petitions is the dark stain that expulsion would leave on the reputation of the Republic. It would “stamp our national character with indelible infamy,” wrote one group from Lexington, New York. Such acts of “enormous injustice,” wrote another group from Pennsylvania, “have rarely been perpetrated by nations calling themselves civilized, and professing to pay a decent respect to their own reputation.” A memorial from the officers of Dartmouth College compared U.S. policy to the “bloody conquests of Cortez and Pizarro.” “The doctrine that force becomes right,” they observed, “has always actuated ambitious and unprincipled conquerors.” They were deeply concerned about the reputation of the Republic “in the eyes of the civilized world.” Expulsion, petitioners said, was “tyrannical and oppressive,” an “unparalleled perfidy,” an “atrocious outrage,” and a “lasting dishonor.”21

This last censure from the “ladies” of Pennsylvania was especially notable since women did not traditionally have a place in politics in the United States. Their memorial to the Senate and the House of Representatives belonged to the first-ever women’s petition drive, organized by Catherine Beecher, an educator who was born into a family of radical reformers. Encouraged by Evarts and the public protests of Cherokee women, Beecher rallied almost 1,500 women from seven northern states. They recognized the novelty of their petitions but insisted on being heard. Eighteen women from Farmington, Maine, acknowledged that the “delicacy of feeling and modesty of deportment which should ever characterize the female sex” would forbid them from petitioning Congress “on any ordinary occasion,” but they rejoiced that they lived in an age that would permit and even encourage them to do so now. They were unduly optimistic. Nevertheless, dispensing with delicacy and modesty, they decried the violation of rights “for which our fathers, fought and bled, and the enjoyment of which so highly distinguishes us as a nation.”22

Likewise, the “sundry ladies” of Hallowell, Maine, asserted, “We would not ordinarily interfere in the affairs of government, but we must speak on this subject.” So too the women of Lewis, New York, who acknowledged that they were “departing from the usual sphere which they occupy.” Nonetheless, they continued, the expulsion of indigenous Americans involved “the principles of national faith and honor which they in common with every other member of society are intrusted to preserve inviolate.” While many women petitioners invoked the traditional concerns of middle-class white women—the sanctity of the “domestic altar,” the well-being of the “feebler sex,” and the “endearments of home”—they were no less vehement than men in their condemnation of U.S. policy.23

Philanthropists were, in the eyes of slave owners, “meek,” “sickly,” and “morbid” (meaning soft), no match for the white men of the South and their “fearless, manly exercise of sovereignty.” The women’s petition campaign was yet another symptom of the effeminacy of the movement, and such gendered criticism found allies among Jacksonians in the North. “FEMALE petitions” were “highly reprehensible,” opined the Pittsburgh Mercury. Even some Whig papers objected to “pretty creatures” involving themselves in politics. The New England Review approvingly quoted John Randolph of Virginia, a congressman famous for his sharp tongue: “The ladies—God bless them—I like to see them any where and every where save in Legislative Hall.”24 Not surprisingly, misogynist comments were picked up and trumpeted by papers in Georgia.

The strutting reached its absurd climax on the floor of the Senate when Missouri’s Thomas Hart Benton, raised in central North Carolina and renowned for his buffoonish pomposity, mocked the “benevolent females” and their male allies. When they retreated in defeat, Benton jeered, the women should place “no reliance upon the performances of their delicate little feet,” for the men would outrun them. “I would recommend to these ladies,” he said, “not to douse their bonnets, and tuck up their coats, for such a race, but to sit down on the way side and wait the coming of the conquerors.” Once the real men arrived—the type that John Quincy Adams would later call the “Anglo-Saxon, slaveholding exterminator of Indians”—the women would be secure.25

~~~

ANDREW JACKSON’S election and address to Congress implicitly invited U.S. citizens to plunder the homes of the South’s longest-standing residents, who, it appeared, were due to be expelled imminently. From the Creek Nation, Neha Micco informed the president that U.S. citizens were stealing their slaves and horses and running them off their land, infringing on rights guaranteed to them by the federal government. In October 1829, Tuskeneah, a Creek leader who was old enough to remember the first U.S.-Creek treaty in 1790, complained that whites stole their property frequently. Without federal protection, he stated, they would be reduced “to a state of penury.”26

Violence spread through the Cherokee Nation as well, fueled not just by Jackson’s inauguration but by the discovery of gold in southern Appalachia in August 1829. Within six months, between one thousand and two thousand intruders were mining the precious metal on native lands. They were “emboldened by indulgence in their trespass,” Cherokee leaders complained to Jackson’s first secretary of war, John Eaton, and “think it an act of trifling consequence” to drive families from their homes.27

The violence threatened to spread and to sharpen internal divisions. In a futile effort to maintain a united front amid deteriorating living conditions, some Creeks beat their neighbors who enlisted to move across the Mississippi, in one instance cutting off the ears of a man and woman. Echoing incidents of frontier violence from the eighteenth century, Creek and Cherokee men attacked the intruders and took their property, acts of repossession from one perspective, theft from another, prompting white Georgians to retaliate. In one particularly vicious assault in the spring of 1830, twenty intruders seized a Cherokee man named Chuwoyee, struck him on the back of the head with a gun, and beat him senseless with clubs and rocks. They threw the incapacitated man over a horse, took him to a camp, and dumped him on the ground, where he remained overnight, exposed to freezing sleet. He died the next morning. Two others escaped, though the assailants stabbed one of them in the chest with a large butcher knife. The marauders threw a fourth Cherokee named Rattling Gourd in jail but released him after the federal government obtained a lawyer for him. In a letter dripping with sarcasm, Cherokee leaders told Jackson, “It cannot be supposed, even tho. our people are Indians (we mean no disrespect) that they can with calmness and submission, witness every act of injustice and plunder by the intruders.”28

Southern elites were quick to blame outside agitators for the violence. The confrontations were “the first fruits of the ‘philanthropic’ movements of the North,” insisted one Georgia newspaper, a charge that would be leveled with more vehemence the following year, when Nat Turner organized a slave uprising in Southampton County, Virginia. Native peoples were “rude and impudent” as a result of the “Fanatics of the North,” the “white savages” who interfered in “local concerns.”29

Five hundred miles separated Capitol Hill and the Creek and Cherokee nations, but it may as well have been five thousand. No one in Washington City consulted the subjects of the grand scheme proposed by Jackson. In late March 1830, a delegation of Cherokee leaders rented accommodations in Brown’s Hotel, halfway between the White House and Congress, but it was Isaac McCoy, rooming in the City Hotel, a block from Jackson’s residence, who had gained the administration’s attention. “I hope [to] exert a favourable influence on the minds of many,” McCoy wrote to his son in late 1829. The zealous missionary-turned-lobbyist had already sent pro-expulsion materials to hundreds of influential people around the country, including scores of newspaper editors and government officials, from the secretary of war down to the chief clerk of the 2nd Auditor’s Office. After meeting with President Jackson and Secretary of War John Eaton, he reported that both were “of the spirit of colonizing the Indians.” The superintendent of Indian Affairs, Thomas McKenney, was also “very friendly.”30

The Senate debate on expulsion began on April 6 and lasted for two weeks, exposing sharp fissures between southern slave owners and northern reformers. The freshman senator Theodore Frelinghuysen of New Jersey led the opposition. An active member of the American Board, the American Bible Society, the American Tract Society, the American Sunday School Union, and the American Temperance Union, Frelinghuysen was also a lifelong supporter of the American Colonization Society. Ironically, his zeal for shipping African Americans to Liberia matched his disgust over deporting Native Americans to the West.31

In his three-day, six-hour-long speech, Frelinghuysen analyzed treaties, discussed the Law of Nations, and appealed to the conscience of the nation, drawing on the language of his friend Jeremiah Evarts as well as on that of native politicians. Native peoples, he stated, had “extended the olive branch” when the colonies were feeble, but now federal and state governments were using “force and terror” to dislodge indigenous families by extending “grinding, heart-breaking” state laws over them. The United States, he asserted, had violated treaties, disregarded native sovereignty, and abandoned its own values.32

George Troup, now representing Georgia in the U.S. Senate, was not well enough to speak on the floor, so the state’s other senator, John Forsyth, led the countercharge, surpassing Frelinghuysen’s lengthy speech by two full hours. Forsyth suggested that it was not possible for a contract with “a petty dependent tribe of half starved Indians” to be “dignified with the name, and claim the imposing character of, a treaty.” He paused to reprimand the deluded “ladies” who had been recruited into service against Georgia. And he asserted that native peoples in the East were “little better than the wandering gypsies of the old world.” He reserved special opprobrium for the Cherokee Phoenix. The newspaper, he stated, spent funds that could have been better used to feed and clothe “half starved and naked wretches” in the Cherokee Nation, though it is apparent that he was more bothered by the periodical’s wide circulation. “It is thus, sir, that the Cherokees have been made so prominent,” he complained. Forsyth also objected to the presence of the Cherokee delegation in Washington City and to the circulars, memorials, pamphlets, and essays that they had penned.33 Adopting a tone that southern orators would hone as the century progressed, he managed to sound both righteous and aggrieved.

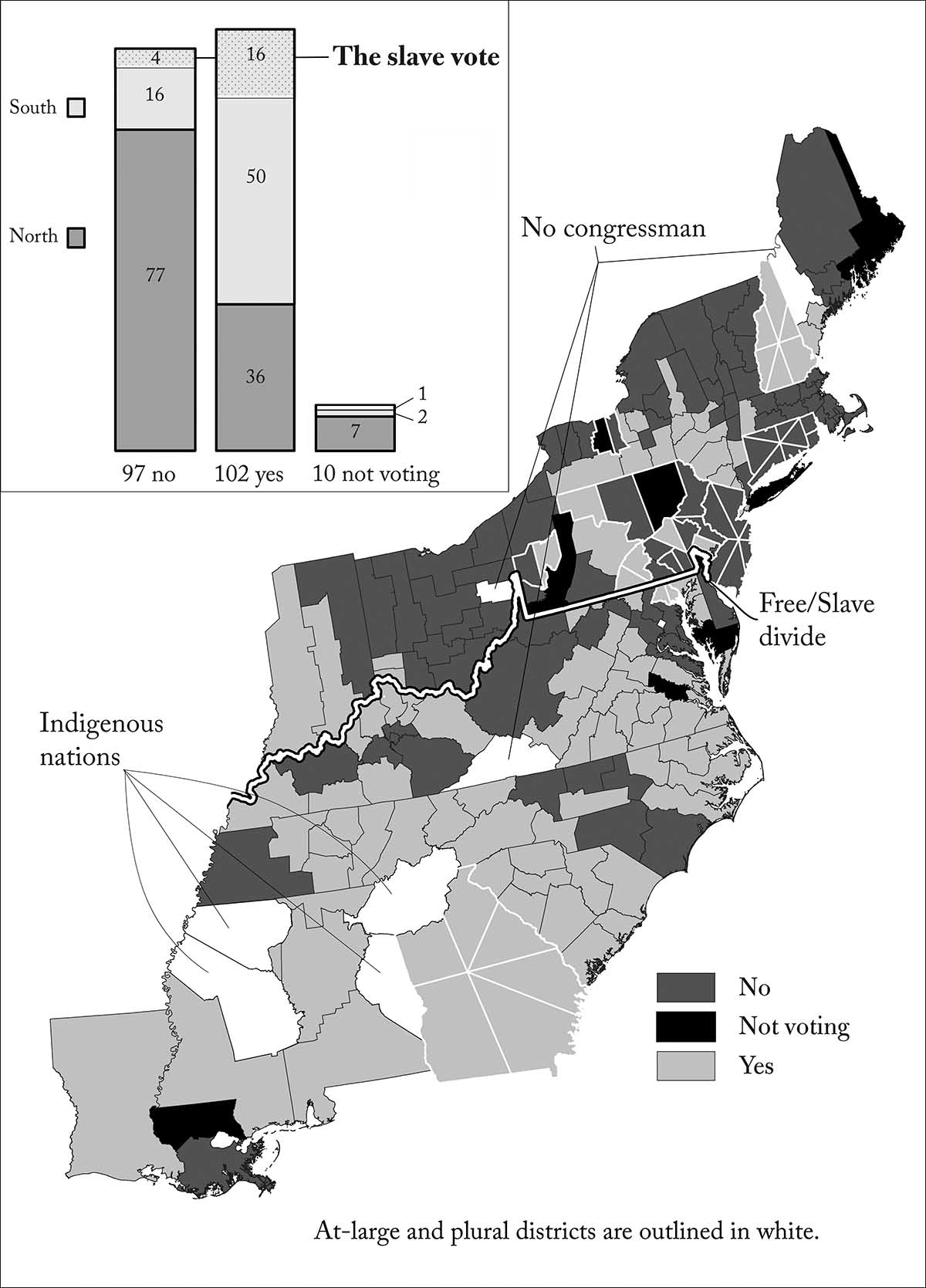

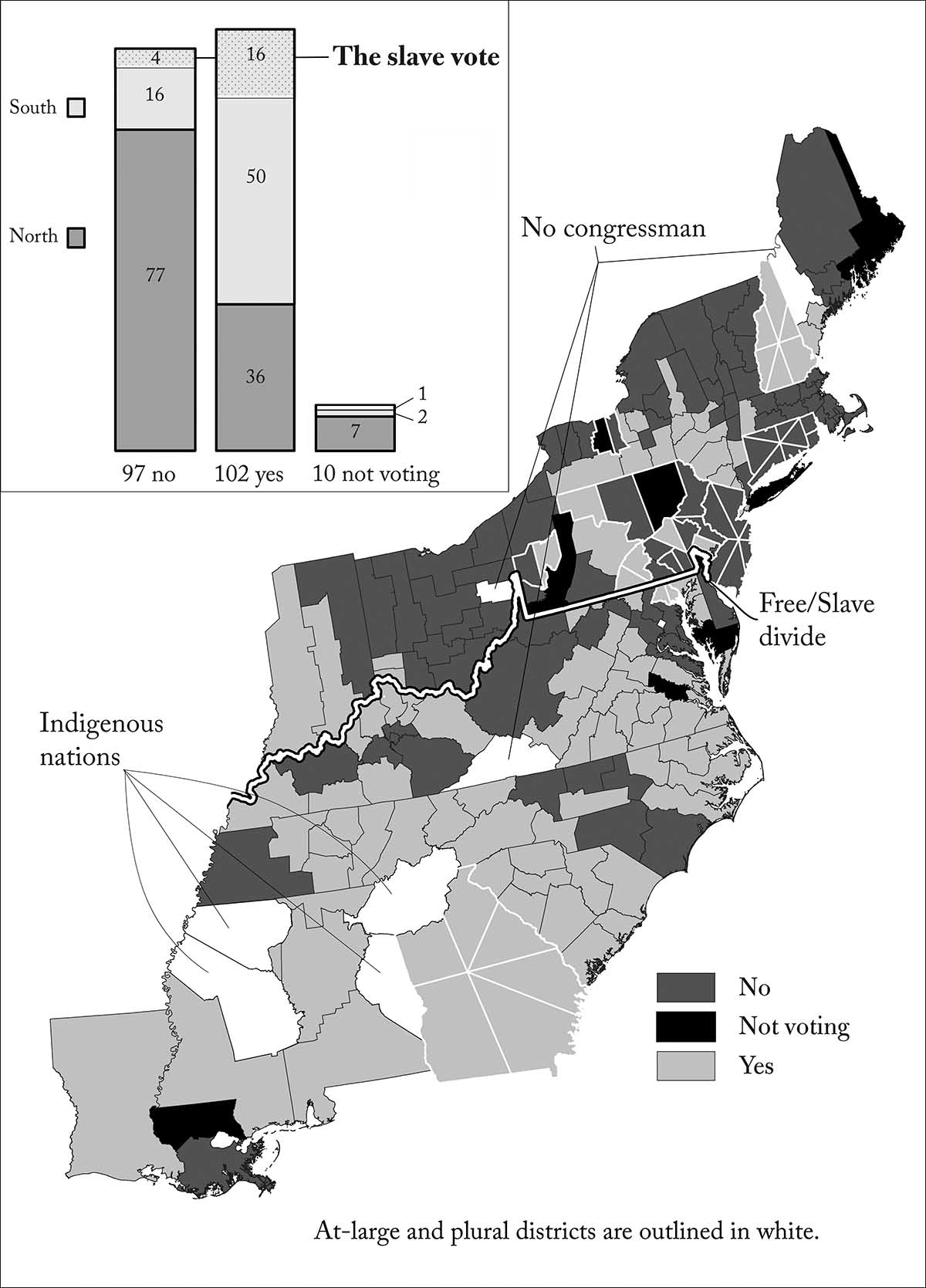

Another twenty hours of speeches followed, but in the Senate, the vote on expulsion was a foregone conclusion. The nation was then evenly divided between slave and free states, and the South could always count on the support of a few northern senators, with business and political leanings toward the cotton South. The final vote, on April 24, stood at twenty-eight in favor, nineteen opposed. Four southern senators (two from Delaware and one each from Missouri and Maryland) abandoned the slave bloc and another was absent, but they were outnumbered by the nine from the North who joined their southern colleagues in voting to expel indigenous Americans.

In the House, by contrast, the vote was entirely uncertain. Five of the seven members of the House Committee on Indian Affairs were from slave states, but in the House at large, only 89 of 209 representatives were from the South. A “more important question never came before any legislature,” wrote Ambrose Spencer, a representative from New York. “It involves questions of national faith,” he declared. Though the debate would not quite determine “the extirpation or preservation of the Indians,” as he imagined, it would irrevocably change the lives of some 80,000 people, and the impact would reverberate for generations. A crowd of indigenous Americans stood listening attentively at the entrance to the House chamber for the length of the debate.34

At the beginning of the year, Isaac McCoy had met with the House Committee on Indian Affairs, which included his friend and ally Wilson Lumpkin, to champion the case for expulsion. Now it was Lumpkin’s turn to push the bill through the House. The Georgia planter had a talent for hiding his extremism beneath a veneer of reason. “Our treatment of the Indians” was “one of our great national sins, and slavery another,” the steadfast advocate of expulsion and the owner of nineteen slaves had once said. After meeting with Lumpkin, one missionary was impressed with his reasonableness and concluded that he appeared “like a man of principle and of piety.” The Cherokee William Coodey offered a harsher appraisal. Lumpkin, he said, was “a cold blooded hypocrite,” who “will say any thing to so serve a purpose whether it be the truth or an untruth.”35

Lumpkin began his speech as the voice of moderation, conceding that some native peoples were “susceptible of civilization” but insisting that their conditions would improve in the West. He quoted McCoy at length (“one of the most devoted and pious missionaries”), mounted a vigorous defense of his home state (“Georgia, it is true, has slaves; but she did not make them such; she found them upon her hands”), and defended Andrew Jackson (“No man living entertains kinder feelings to the Indians”). Northern reformers were “well paid” hypocrites and “intermeddlers,” he charged, out to line their pockets at the expense of native peoples. To save the Indian, he concluded, echoing his friend McCoy, they must be expelled.36

The opposition had the better argument. It was easier to contend that treaties were in fact treaties than to assert that they were something less. The chair of the House Committee on Indian Affairs, John Bell of Tennessee, insisted that treaties with native peoples were “a mere device, intended only to operate upon their minds, without any intention of being carried into effect.” Henry Storrs of New York countered, “It requires no skill in political science to interpret these treaties.” “The plainest man,” he continued, “can read your solemn guaranties to these nations, and understand them for himself.” Maine’s Isaac Bates, imagining a conversation with the president, was more dramatic:

Sir, they produce to you your treaty with them. Is this your signature and seal? Is this your promise? Will you keep it? If you will not, will you give us back the lands we let you have for it? The President answers, no; and the Congress of the United States answers here is money for your removal.

Jackson, he said, set fire to the city and would not put it out, though he was “its hired patrole and watch.”37

It was also easier to argue by invoking republican values than by resorting to callousness and derision. The advocates of expulsion mocked those who “indulge” their “tears at the extinction of the Indian race.” “The Indians melt away before the white man, like the snow before the sun!” exclaimed Richard Henry Wilde of Georgia. “Well, sir!” he continued. “Would you keep the snow and lose the sun!” By contrast, Henry Storrs of New York called on Andrew Jackson to “vindicate the public faith” of the country, and William Ellsworth of Connecticut reminded congressmen that “the eyes of the world, as well as of this nation, are upon us.” “I conjure this House,” he concluded, “not to stain the page of our history with national shame, cruelty, and perfidy.” House member John Test of Indiana acknowledged that both senators from his state had voted for the bill. He, however, felt “bound in conscience, in honor, and in justice” to speak against it.38

Legal coercion, the strategy secretly devised by southern senators and representatives in the winter of 1826–27, lay at the heart of the debate. “We are told,” petitioned the Cherokees, “if we do not leave the country, which we dearly love, and betake ourselves to the western wilds, the laws of the state will be extended over us.” Creek petitioners spelled out the consequences. Alabama laws were designed to plunder them, “to drag our people to distant tribunals to answer complaints, not before a Jury of peers, or vicinage, but before a Jury of strangers who speak a Language as strange.” The object, they concluded, was less to exercise sovereignty than to “expel our Nation from their country.”39

Congressman Edward Everett of Massachusetts, a renowned orator and onetime Harvard professor, took up this theme on the floor of the House. State laws, Everett asserted, “are the very means on which our agents rely to move the Indians”:

It is the argument first and last on their tongues. The President uses it; the Secretary uses it; the commissioners use it. The States have passed the laws. You cannot live under them. We cannot and shall not protect you from them. We advise you, as you would save your dear lives from destruction, to go.

Legal force “is the most efficient and formidable that can be applied,” he continued. “It is systematic, it is calculated and measured to effect its desired end.” Representative Test of Indiana put it more vividly. Native peoples would be negotiating their expulsion “with the horrors of a penitentiary and hard labor staring them in the face, with a rope around their necks, a hangman by their side, and a gallows erected over their heads!”40

The debate brought the House to a fever pitch. “I have never witnessed, in any deliberative body, more violence and excitement,” wrote one onlooker. The chamber was so evenly divided that Speaker of the House Andrew Stevenson—said by one adversary to be among the “Slaves of the Executive” who were guilty of “subserviency and prostitution”—cast the deciding vote on three pivotal motions. It is unlikely that the bill would have survived without his intervention.41

Representatives from Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi unanimously supported the expulsion of native peoples in order to expand slavery, and almost every other southern member backed the policy for the same reason. They were joined by representatives from New York and New Hampshire, strongholds of the Democratic Party in the North. That was not enough, however, to get the bill through the House. The final vote would hinge on the large delegation of twenty-six House members from Pennsylvania. Though many of them were “the General’s friends,” wrote Andrew Jackson’s future vice president, Martin Van Buren, only four were reliable votes for the pro-expulsion forces. The others lived in dread of giving offence to the large population of Pennsylvania Quakers, who were among the most ardent petitioners against expulsion. To secure a victory, the administration needed to peel off three of the twenty-two members of the delegation who were opposed to the president’s key policy initiative.42

Jackson resorted to “threats and terrors,” said Congressman William Stanbery of Ohio. The administration reminded the House members that the legislation was the president’s “favorite measure” and warned them that they would be denounced as “traitors and recreants” if they failed to fall in line. Jackson, they learned, would work to defeat the holdouts at the next election, a threat that was said to be “as terrifying” to some as the guillotine in revolutionary France. One representative who had been browbeaten by Jackson’s allies stated that “the highest authority” had told him that the bill was “necessary for the preservation of the Indians,” a contention that was as much menacing as reassuring.43

When the day of the final vote arrived on May 26, two congressmen from Pennsylvania, James Ford and William Ramsey, were missing, and business was suspended while the sergeant-at-arms went searching for them. Ford, a sawmill and gristmill owner from near Pittsburgh, appeared soon afterward, but Ramsey, said to be sick, was not in his lodgings and could not be found. Finally, after more than an hour’s delay, said one eyewitness, the fifty-year-old lawyer arrived “tottering” into the chamber, “with all the appearance of being very sick.” The question, “Shall the bill pass?” was put to the House. The act passed by a margin of 102 to 97, with both Ford and Ramsey switching sides and voting in favor of the legislation. “The prayers of our memorials before the Congress of the United States have not been answered,” a despondent John Ross told the Cherokee General Council.44

Two hours after the tense vote, a quarrel broke out between Ramsey and South Carolina Representative George McDuffie over the federal tariff. The tariff protected northern industries from foreign competition, but McDuffie, like other planter-politicians, opposed the tax, since it raised the price of the manufactured goods they needed to operate their slave labor camps. Still chafing from his controversial vote, Ramsey accused his southern colleague of depriving the government of income, even while drawing on the Treasury to expel indigenous Americans. When McDuffie called Ramsey “an ignoramus and an old woman,” Ramsey abandoned “all appearance of indisposition” and responded vehemently, leading a witness to speculate that the Pennsylvania congressman had feigned illness in the hope of avoiding the expulsion vote altogether. Ramsey later claimed that he had been cheated in the bargaining for his vote.45

Ramsey’s theatrics, and the fact that he was one of three to switch sides and secure passage of the bill, made him a target of scorn in Pennsylvania. In Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania Intelligencer called out the faithless congressman and the state’s other representatives who had voted “to drive the defenceless Indians from their homes.” Returning to the subject in mid-June, the newspaper’s ire had only grown. Singling out Ramsey once more, it speculated bleakly that for native peoples nothing remained but “extermination.” Soon, it predicted, “some blood stained victor” in the Cherokee Nation would close his correspondence to the secretary of war by announcing the final destruction of the Cherokees. “This morning,” the newspaper imagined the letter stating, “we found fifteen of them secreted to avoid detection and immediately despatched them.”46

While Jackson pressured and threatened members of Congress to vote for expulsion, there is also a structural explanation for the outcome. The bill, as Martin Van Buren succinctly observed, was a “southern measure,” and the South had an undemocratic advantage. As a result of the Constitution’s three-fifths clause, slave states wielded an additional twenty-one votes in Congress in 1830.47 The politics were truly perverse. Planters used the votes accorded to them for owning slaves to make room for more slaves. By a narrow margin of five votes, they succeeded in passing an act designed to open up vast territory for industrial-scale cotton production. Through its passage, hundreds of thousands of fertile acres—the ancestral lands of native peoples—would become part of the empire of slave labor camps that was rapidly expanding across the Lower South.

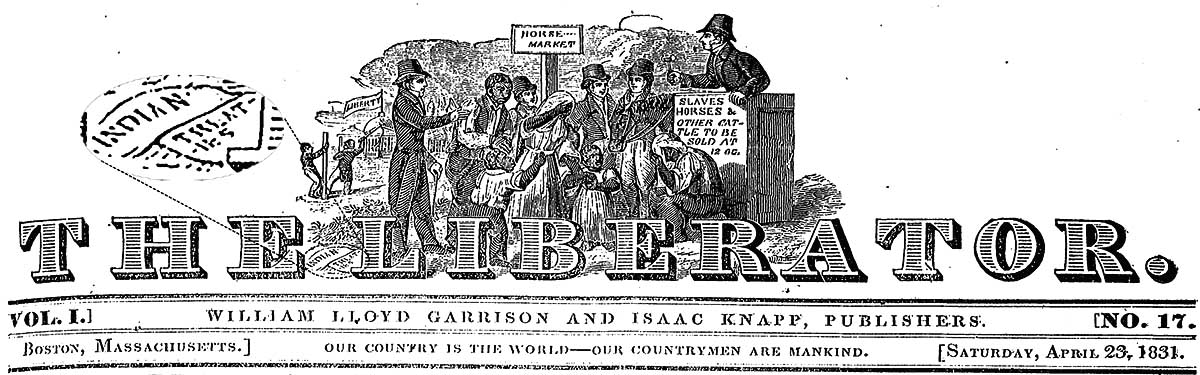

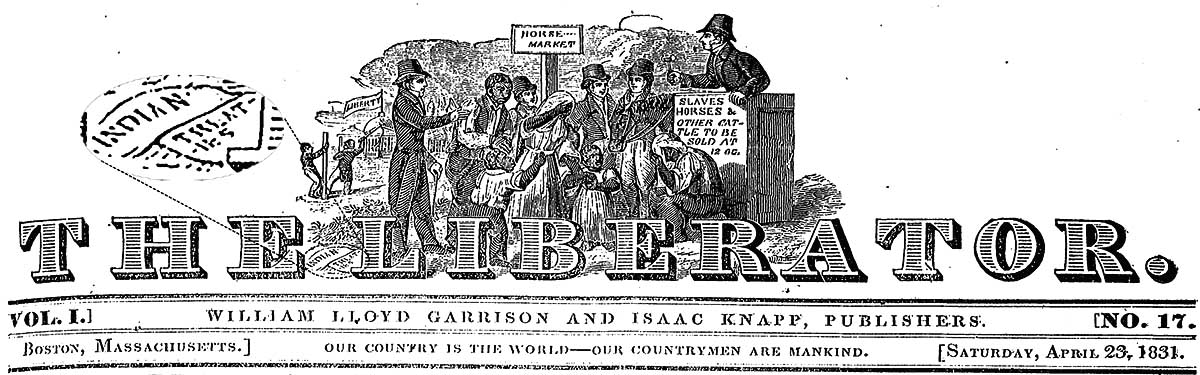

Beginning with issue of April 23, 1831, The Liberator’s masthead captured the relationship between the expansion of slavery and the expulsion of native peoples. A planter purchases slaves at an auction, while “Indian Treaties,” highlighted in the inset, lie beneath his feet.

The righteous anger that many people felt for what they called a “national disgrace” was somewhat undercut by their opponents’ insistence that native peoples had long been oppressed and dispossessed in both the North and the South. The sympathy of northern reformers, according to one hostile congressman, seemed sudden, shallow, and hypocritical. “The Indians had nearly disappeared from eleven of the thirteen old States,” he rightly observed, and “heretofore their gradual disappearance has produced no violent sensation.” Another wondered if the congressmen from Massachusetts, Maine, Connecticut, and New York who “zealously” spoke against the bill had bothered to examine the discriminatory laws of their own states. The Georgia Journal printed a series of northern laws showing how “the poor Indians—these inoffensive and oppressed sons of the forest—were treated by the immaculate puritans and their descendants.” In Connecticut, native peoples were subject to state morality laws; in Rhode Island, they were constrained by a 9 P.M. curfew, on pain of public whipping; in Massachusetts, bounties were offered for “Indian heads”; in New York, the state forbade the Senecas and other native nations from trying and punishing crimes. The allegations were mostly valid; northern states had in fact led the way in the extension of sovereignty over indigenous nations.48

Voting by district in the House of Representatives on the “Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians,” May 26, 1830. I have subdivided Georgia, New Jersey, Connecticut, and New Hampshire, which had at-large elections. I have also subdivided plural districts with multiple representatives in Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania. The accompanying bar graph illustrates that the extra representatives accorded to southern states by the three-fifths compromise made the difference in the passage of the bill.

Since the Revolution, Americans had struggled with little success to ease the tension between radical republican values and the racial hierarchy in the United States, and they failed once again when Congress voted to expel indigenous peoples. While white southerners cynically dismissed the stirring rhetoric of their opponents, at least a few self-questioning and thoughtful northerners recognized the difficulty they had living up to their ideals. “It is a singular feature in our nature that we often condemn in others what we will do ourselves,” one writer, identified only as J.W.B., observed in the New-Haven Register. To make the point, the anonymous author imagined a dialogue between “Friend A” and “Public Spirit.” Friend A: “Have you heard how the Georgians are driving off the Indians?” Public Spirit: “Yes! and my blood boils with indignation at the deed!” But when the subject turns to the creation of a college in New Haven to educate “colored youth,” Public Spirit responds quite differently: “Colored youth! what do you mean, Nigger College in this place! Why, friend A. have you lost your senses!” “You get a gang of negroes here,” Public Spirit protests, “and you would soon find that the value of real estate would fall in this place at least twenty-five percent.” This scenario was not fictional, for at a rancorous public meeting, the citizens of New Haven did oppose the creation of such a school, even while they were sending anti-expulsion petitions to Congress. In the dialogue, a resident of Georgia has the last word: “You hypocritical turncoats! . . . When you cease from driving off the blacks from your own cities, then come and tell me of the wickedness of driving off the Indians.”49

Public spirit also fell short when the subject turned to the treatment of indigenous Americans in the North. In New York, politicians would spend the 1830s dispossessing the Senecas in order to clear the way for canal construction, and in Massachusetts, state leaders faced unrest from the Mashpees of Cape Cod, who in 1833 began protesting centuries of mistreatment. The “Indian’s Appeal to the White Men of Massachusetts,” a brief statement drafted under the guidance of William Apess, focused attention on the gap between rhetoric and action. “How will the white man of Massachusetts ask favor for the red men of the South,” Apess wondered, “while the poor Marshpee red men, his near neighbors, sigh in bondage?” “Will not your white brothers of Georgia tell you to look at home, and clear your own borders of oppression before you trouble them?” he asked. Unlike southern planters, however, Apess wished not to undermine protests over expulsion in the South but to extend them to the North, and he went out of his way to praise the “distinguished” people “who advocate our cause daily.” They “are to be prized and valued,” he wrote, urging them not to tire in the cause.50

The charges of hypocrisy in Congress effectively muddied the debate, and nearly two centuries later, it is still difficult to see clearly through the muck stirred up by southern planter-politicians and their northern allies. The debate can appear as another grim chapter in the centuries-long story of dispossession, in which native peoples would lose no matter what. And yet the charges of hypocrisy, then and now, are largely irrelevant to the political act. Every legislative action is the product of self-serving alliances, principled stands, and distasteful compromises. Those who opposed expulsion were no less right because some of them fundamentally despised Native Americans, acted solely for reasons of party allegiance, or struggled to live up to their lofty ideals closer to home. More to the point, their motivations made no difference to the people being deported. Through all of the mudslinging and rhetorical smokescreens, indigenous Americans stayed focused on the debate’s central question: Would the United States disregard its treaties, ignore their appeals, and launch an ambitious and unprecedented plan to deport 80,000 people?

~~~

THE “ACT to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi” gave the president the authority to mark off territory “west of the Mississippi” and to exchange it with indigenous people living within the bounds of states or territories for a whole or part of their current lands. Deported families were to receive payment for their improvements and “aid and assistance” during and for one year after expulsion. In an ambiguous sop to secure needed votes, the House proposed an amendment accepted by the Senate: “Nothing in this act contained shall be construed as authorizing or directing the violation of any existing treaty between the United States and any of the Indian tribes.” Congress appropriated the absurdly small sum of $500,000 to carry out the provisions of the law.51

The act said nothing about how the exchange of lands was to be negotiated. By treaty? By contract? With the threat of violence? Nor did it explain how indigenous lands were to be valued. Improvements were to be appraised, but by whom and with what controls? As for providing “aid and assistance” in moving, the act gave no details about the amount or quality of support, or whether private contractors or the federal government would do the providing. Perhaps most egregiously, it said nothing about the mechanics of transportation, the wagons, ox teams, steamboats, food, tents, clothes and shoes, and medical supplies that would be needed to move thousands of families, including elderly grandparents and young children, across hundreds of miles to the west, over rudimentary roads and uncharted lands. Who would supervise the endeavor? What means would they have at their disposal?52

The United States was embarking on a grand scheme with minimal preparation and little good will for the people targeted by the law. Jackson believed he could drive indigenous Americans west by being remorseless and strong-willed, but his confidence quickly gave way to the hard truth that the country’s oldest residents were determined to remain in their homelands. Warnings became threats, and threats were soon made at the point of a bayonet. By the mid-1830s, U.S. troops were force-marching people in chains in Alabama and pursuing starving families from camp to camp in Florida. The descent from Aboriginia to exterminatory warfare against desperate families was swift. Within a few years, McCoy’s fantasy would become a nightmare.

.” The expression literally means, “We know what the leaders said, or are they going to cover up that we met?” To clarify the expression for Congress, Cherokees paraphrased it as, “We know the treaties existing between us and the United States, and will you pass laws over us?” Another memorialist wrote, “

.” The expression literally means, “We know what the leaders said, or are they going to cover up that we met?” To clarify the expression for Congress, Cherokees paraphrased it as, “We know the treaties existing between us and the United States, and will you pass laws over us?” Another memorialist wrote, “ ,” meaning “People who live in Kawonugi all of the 1,100 strong men[,] the land they love it.” The phrase “the land they love it,” which appeared more than once among the signatures, had a particular resonance in the Cherokee Nation, for it signaled a decisive rejection of further land cessions—exactly what white southerners feared most.6

,” meaning “People who live in Kawonugi all of the 1,100 strong men[,] the land they love it.” The phrase “the land they love it,” which appeared more than once among the signatures, had a particular resonance in the Cherokee Nation, for it signaled a decisive rejection of further land cessions—exactly what white southerners feared most.6