~~~

WHILE THE commissary general labored over plans to launch a second year of Choctaw deportations, across the street on the second floor of the War Department building, Secretary Lewis Cass was supervising military operations against the Sauk and Meskwaki (or Fox) people on the Wisconsin and Mississippi rivers. The Sauks’ central town, Saukenuk, was situated on the Rock River, a few miles above its junction with the Mississippi, not far from present-day Davenport, Iowa. Surrounded on three sides by a brush palisade, it was organized around a large square and contained more than one hundred wood and bark longhouses that extended fifty or sixty feet, each capable of lodging as many as sixty people. North of the town, the villagers cultivated eight hundred acres of corn, beans, and squash. To the alarm of federal officials, their population, including that of the surrounding villages, exceeded six thousand people and was expanding.1

The “three sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—conjure stereotypes of an idyllic, unspoiled America, but in fact lead mining was the fastest-growing industry in Sauk, Meskwaki, and neighboring Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) communities. Long before the arrival of Europeans, native peoples had mined lead sulfide, using the metallic blue-black crystals for religious purposes and to produce paint pigment. Archaeologists have recovered 265 pounds of the material from Mound City, the eighteen-hundred-year-old ceremonial center on the Scioto River in Ohio. By the nineteenth century, the ore had acquired an additional use in manufacturing ammunition, and the U.S. economy, by offering access to national markets, had transformed the occasional native industry into a profit-seeking enterprise. Indigenous women, the traditional miners in the region, seized the opportunity. At one “lead house” on the Mississippi River, ten to fifteen Sauk canoes arrived daily, each carrying two thousand pounds of the metal. “I was kept from morning to night weighing and paying in goods,” recalled the store owner. By one estimate, native residents mined as much as 800,000 pounds of lead in the summer of 1826. Colonists swarmed into the region to participate in the lead rush, founding towns such as Galena (named for lead sulfide), Mineral Point, Hardscrabble, and New Diggings. The newcomers, who erected shanties and sod huts that compared poorly with the comfortable lodgings of the Sauks, lived in uneasy proximity to the region’s longtime landowners.2 Inevitably, their arrival sparked conflict.

By December 1828, U.S. citizens were moving into Sauk houses and displacing the residents, and in 1831, the Sauks finally abandoned their villages and crossed the Mississippi. A year later, however, about one thousand of them returned, creating a tense standoff. The seasoned commander of the army’s Western Department, Edmund Gaines, was then recovering from influenza and rheumatism in Memphis, Tennessee. Since Gaines had spoken out against the president’s favored policy of expelling native peoples, the Jackson administration was happy to pass over him and give command to General Henry Atkinson, a North Carolinian with scant battle experience and little tactical sense. On May 5, 1832, the army’s commanding general in Washington City ordered Atkinson, with the assistance of Colonels Zachary Taylor and William S. Harney, to “drive the Sac’s and Foxes over the Mississippi.” 3

Nine days later, a company of drunken Illinois rangers attacked the Sauks and were routed, despite their sizable numerical advantage, marking the start of the U.S.-Sauk War. The conflict is often called the Black Hawk War, after the Sauk leader who rallied people to the cause. An example must be made of the Sauks, Secretary of War Cass declared, “the effect of which will be lasting.” The Galenian urged the governor to “carry on a war of extermination until there shall be no Indian (with his scalp on) left in the northern part of Illinois.” Galenians, it boasted, were “ready to exterminate the whole race of the hostile Indians.” 4

With an army of 450 regulars and between 2,000 and 3,000 volunteers, including a twenty-three-year-old greenhorn named Abraham Lincoln, Atkinson pursued the Sauks without success for a month. By mid-June, the ongoing war was becoming an embarrassment for President Jackson, and he ordered reinforcements under General Winfield Scott to move west from New York to Fort Armstrong, an outpost on Rock Island in the Mississippi River, south of Galena and close to the main Sauk town of Saukenuk. The Sauks “must be chastised,” Jackson scolded, “and a speedy & honorable termination put to this war, which will hereafter deter others from the like unprovoked hostilities by Indians on our frontier.” 5 The mission did not go as planned.

~~~

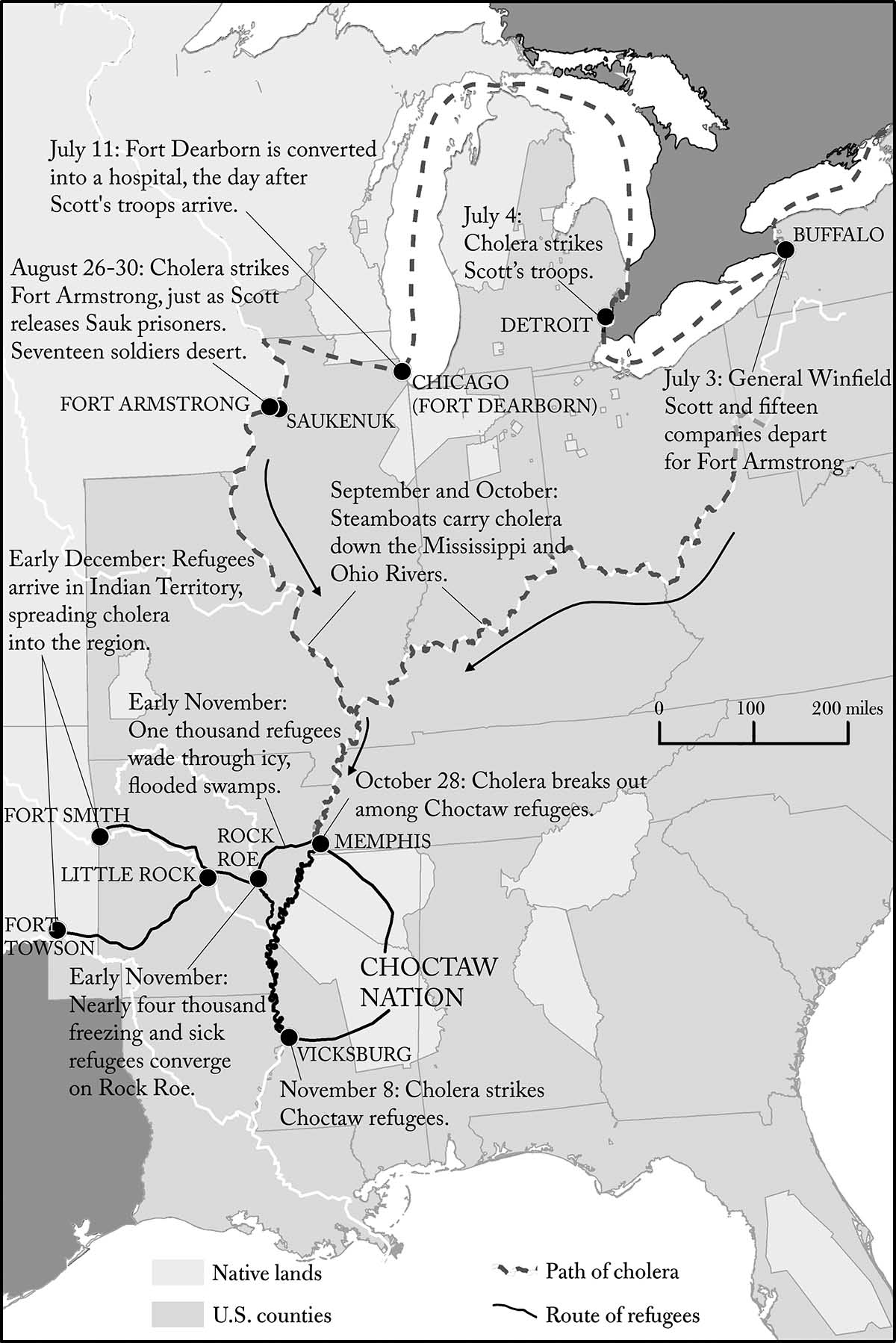

VIBRIO CHOLERAE had not yet arrived in North America when George Gibson began planning the route for the second round of Choctaw deportations. The comma-shaped bacteria first appeared on the continent on Grosse Ile, on the St. Lawrence River east of Quebec City, in the late spring of 1832, shortly before Andrew Jackson ordered troops to Fort Armstrong to confront Sauk villagers. The disease had journeyed from India, by way of Afghanistan, Russia, Germany, and Britain, killing tens of thousands of people along the way. From Grosse Ile, infected persons carried the microbes up the St. Lawrence, through Lake Ontario to Buffalo. There, General Winfield Scott, his staff, and fifteen companies of artillery and infantry boarded the steamboats Sheldon Thompson and Henry Clay, bound west through Lakes Erie, Huron, and Michigan for Fort Dearborn in Chicago. From Fort Dearborn, they would march overland to Fort Armstrong to do battle with Black Hawk and the Sauk people. The expedition embarked on July 3, but one day later a soldier aboard the Henry Clay suddenly sickened, dying that same night. Officers ordered his body thrown into the Detroit River.6

V. cholerae prefers warm brackish waters, where it attaches to zooplankton and phytoplankton. If ingested by a human, it can pass through stomach acid intact and colonize the upper small intestine, where it produces a toxin that the body flushes out with watery vomit and a voluminous and distinctive rice-water diarrhea. Infected individuals may lose several quarts of fluid and rapidly become dehydrated. Blood pressure collapses, eyes recede in the skull, skin becomes shriveled and pallid, and victims go into shock. About half of those who are severely infected will die, some within a few hours after the onset of symptoms. “You remember Sergeant Hoyl,” wrote one of Scott’s officers. “He was well at 9 o’clock in the morning—he was at the bottom of Lake Michigan at 7 o’clock in the afternoon!” Food and water that are contaminated with the victim’s copious effusions introduce the microbe to its next host.7

By July 16, cholera had killed thirty-four soldiers from the Henry Clay, and many others had deserted and died on the road, reducing the detachment of 370 troops to 68. Meanwhile, the microbe spread to the Sheldon Thompson on the way to Chicago, and General Scott’s men threw twenty-one corpses into Lake Michigan. The contaminated bodies washed up on Chicago’s shoreline. By July 19, of the 190 enlisted men on the Sheldon Thompson, 62 had died and 51 were ill. At the time, most people believed that the disease arose from lax morals, excessive anxiety, or atmospheric peculiarities, but General Scott was the rare “contagionist” who held that it could be transmitted between individuals. By posting notices in Chicago newspapers and writing open letters warning of the deadly contagion, he attempted to erect a “paper barrier” around the city. Such warnings proved ineffective, however, and mounted rangers soon carried the bacteria nearly 200 miles west to Fort Armstrong. In the space of a week, cholera struck 146 troops at the outpost and killed 26. Twenty more were expected to die. Scott was mortified. Without engaging in battle, he had “brought disease and death” upon his soldiers.8

Just as Scott’s diminished forces were arriving, General Atkinson’s army of volunteers and regulars managed to defeat the Sauks in battle. Devastation reigned. In late July, soldiers pursued the surviving families west toward the Mississippi, passing corpses on the trail, the victims of starvation, disease, and gunshot wounds. They captured an elderly Sauk man, “extracted some information from him,” and “coolly put him to death.” On August 2, federal troops and state militia pinned the largest group of survivors against the east bank of the Mississippi River and began “the work of death,” as one scout put it. They killed at least 260 Sauks, with some 200 escaping across the river. Ho-Chunks, Menominees, Dakotas, and Potawatomis, settling old scores and currying favor with the United States, hunted down survivors, bringing in emaciated villagers and their starving children.9

Because the federal government claimed that the Sauks had ceded their eastern lands in a disputed treaty in 1804, the villagers were not formally subject to the 1830 “Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians.” Nonetheless, U.S. citizens recognized that there was an uncomfortable connection between the federal policy to expel Native Americans and the mobilization of federal troops against the Sauks. What if the Sauks’ disaffection spread? Would the United States exterminate all native peoples who refused to relocate? A Washington newspaper concluded that every “dispassionate man” would now see the necessity of the “immediate removal of the Indians beyond the sphere of our settlements.” In the patriotic afterglow of victory, one skeptic insisted that the U.S.-Sauk War had its origins “in the injustice of the whites” and the “ignorance of the Indians.” “But,” he stated sharply, “there are no historians among the Indians.”10

Winfield Scott, Zachary Taylor, and William Harney would soon be sent from Sauk country south to Georgia and Florida to fight other deep-rooted families. In the meantime, a different vector connected the military mobilization on the upper Mississippi with the federal operation to deport people in the South. In late August, General Scott released several Sauk prisoners from confinement at Fort Armstrong, hours before cholera erupted in the barracks. The freed prisoners carried V. cholerae into indigenous communities in the West. How many native people died is unknown, though the chilly fall weather and dispersed populations surely lessened the toll.11 (V. cholerae becomes dormant in cold temperatures.) Deserters from Fort Armstrong also dispersed the microbe far and wide as they fled into the countryside. Steamboats stood ready to carry the disease farther down the Mississippi to the riverport cities of Memphis and Vicksburg, where thousands of Choctaw refugees would soon converge.

~~~

THOUGH U.S. officials had not learned many lessons from the disastrous first year of deportations, they conceded that Arkansas Post was a poor staging ground, since supplies and wood were scarce on the river bluff. Instead of congregating there, Commissary General Gibson determined that this time Choctaw deportees would march to Memphis or Vicksburg, on the east bank of the Mississippi. There they would board steamboats destined for Rock Roe, a landing about one hundred miles up the White River, in east-central Arkansas. From Rock Roe, some of the dispossessed would walk over two hundred miles west to Fort Smith, on the border of Arkansas and Indian Territory, while others would turn south-southwest at Little Rock, heading to Fort Towson, a journey of 350 miles.12

Operations began in October 1832, just as cholera was descending the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. In Mississippi, a recent state law had invited U.S. citizens to settle on Choctaw lands, so many dispossessed families were desperate to escape the army of squatters and speculators that had invaded their nation. As thousands of Choctaws assembled at staging areas for the trek west, federal Indian agents raced to load wagons and break camp in a futile effort to beat V. cholerae to Memphis and Vicksburg. Each steamboat descending the Mississippi was a cause for alarm. On the journey downriver, seven people died on the Express, two on the Constitution, and five on the Freedom. Meanwhile, over two thousand refugees were converging on Memphis. Francis W. Armstrong, the federal officer conducting the detachment, wrote to Gibson on October 21, “I fear that we are to encounter the cholera with our Indians.” A week later, the dreaded disease struck the refugees at Memphis.13

A separate group of Choctaws headed for Vicksburg. Numbering seventeen hundred, they set off from the eastern part of the nation in early October and encountered difficulties almost immediately. Rains clogged the road with mud and turned low-lying areas into swamp, and dysentery spread through the crowded and unsanitary camps. Within a week—during which four babies were born and a child died—word reached the train of refugees that cholera was in Vicksburg. As they approached the northern edge of the city, they encountered people fleeing the epidemic. The wagon drivers threatened to desert, and one frightened federal agent was dismissed and admonished “to forebear the expression of his fears.” It was imperative not to alarm the refugees. On November 8, cholera entered their camp.14

Most of the refugees at Memphis and Vicksburg went to Rock Roe by steamboat. Plying the Mississippi and White rivers, the transports called at deserted woodyards to fuel their boilers. The workers, afraid of making contact with the diseased deportees, had abandoned their posts. “Scarce a boat landed without burying some person,” wrote a federal agent. Over a thousand people who were camped outside Memphis refused to board the contaminated vessels, and instead chose to set out on foot. Taking what happened to be the lesser of two evils, they followed a newly constructed military road. But their new route was plagued with problems, since it passed through low-lying lands that were frequently flooded. In the first twenty miles alone, the road crossed Mill Seat Bayou, Blackfish Bayou, Shell Lake, Biven’s Lake, and Beaver Lake before arriving at Despair Swamp. Even outside of the normal spring floods, travelers struggled to traverse the unusual landscape. The terrain harbored a confusion of lakes, bayous, cypress swamps, and marshy grounds covered with huge gum, sycamore, oak, and hickory trees. The occasional canebrake, a dense field of woody stalks rising twenty to thirty feet high, was impassable. Some low-lying areas regularly held fifteen to twenty feet of standing water. After a week of wading through knee to waist-deep water, at least seven Choctaws had died from cholera or exposure, and the families had covered only forty of the ninety miles to their destination.15

As cholera moved down the Mississippi in the fall of 1832, Chickasaw deportees converged on Memphis and Vicksburg.

Because no Choctaw left a full account of this dismal period, we must rely on the writings of unsympathetic federal agents for descriptions of the “cholera times.” One federal officer complained that the Choctaws were “perfectly inefficient” and willing to work only when compelled. On one occasion, he recounted, he and his assistant were obliged to dismount to lift a dying man in the final stages of cholera into a cart. More than fifty refugees stood by, he wrote, for “sheer want of energy.” It seems not to have occurred to him that the Choctaws feared catching the disease. “Having received assistance once,” he remarked, “they would not bury their own dead afterward without asking help.” On another occasion, a thirty-year-old lieutenant faulted the refugees for refusing to abandon an elderly but still healthy man named Etotahoma. The beloved leader was “old, lame, and captious,” complained the officer, and had delayed the party considerably.16

The same officer, Jefferson Van Horne, composed a vivid account of his own suffering from V. cholerae northwest of Vicksburg. Attacked by the microbe, he retired to a nearby cabin, where his frightened host removed a floorboard, leaving a hole through which Van Horne vomited and defecated. After a day of “constant purging and vomiting,” Van Horne took a large dose of opium and calomel, a toxic purgative. Near midnight, as the violent attack continued, his host evicted him, explaining that he had a large family whose lives were at stake. After begging in vain to remain in the cabin by the fireside, Van Horne rolled himself in a blanket and stumbled into the cold, walking three quarters of a mile over frost-covered ground to his tent. “My suffering for two or three days exceeded any thing I ever experienced,” he wrote.17 How many Choctaws went through similar struggles without the benefit of a warm cabin or even a canvas tent is unknown.

West of the Mississippi, the deportees were under the authority of Francis W. Armstrong of Tennessee, a patronage employee who had obtained his position because he “talked loudly” in support of Jackson during the election campaign of 1828. It also helped that his brother was a veteran of the 1813–14 U.S.-Creek War and, more to the point, “a pet of the President.” One disgruntled and recently dismissed federal agent observed that Armstrong and his fellow officers “were worse than useless.” Yet Armstrong did possess one distinguishing qualification for the job: When efficiency demanded it, he could be uncompromising. The refugees had been “spoiled” the year before, he asserted. By one account, it particularly irked him that in 1831 the Choctaws had been permitted to carry their hominy mortars, the stone grinders that were essential to processing corn, their staple food. Armstrong would allow no such indulgence. When the steamboats stopped for wood, he stationed a guard to beat the refugees back from the shore, though they were desperate to relieve themselves on land, away from the overcrowded and filthy transports. The draconian measure “largely economised both time and means,” approved one officer, but it also may have unintentionally contributed to the spread of V. cholerae. At Rock Roe, Armstrong refused to distribute blankets to the refugees, leaving them “naked, wet and cold.” He was a “tyrant and cruel,” said one antagonist. Armstrong was clear in his defense: His detractor was “outrageous in favour of the poor Indians.”18

The road west from Rock Roe offered no relief. The daily log of one group of seven hundred refugees catalogs the toll. On November 14, the day they departed the encampment, several came down with cholera, and a child died. The next day, three more caught the disease. On November 16, during a march of eleven miles, another child died. The party walked eighteen miles the next day, and two more became ill. When the weather turned cold, the refugees continued through torrential rain. Over the next week, eight new cases of cholera appeared, and measles erupted. Four more people died. On December 8, after nearly a month on the road and after six deaths, they arrived at Fort Towson.19

The overall death toll remains unknown. Hundreds became ill, but the winter weather may have spared refugees the worst of the epidemic. One group of 455 aboard the steamboat Reindeer incurred fourteen deaths on the way to Rock Roe, a mortality rate of 3 percent. Another group of 1,200 “suffered dreadfully with the Cholera.” A federal officer reported that the “woods are filled with the graves of its victims.” Armstrong approached the crisis by insisting to those at risk that all was well. “We have been obliged to keep every thing to ourselves, and to browbeat the idea of the disease,” he confessed, “although death was hourly among us, and the road lined with the sick.” “Fortunately, they are a people what will walk to the last,” he wrote to the commissary general, “or I do not know how we could get on.” One thing kept the refugees going. Approaching Fort Towson after hundreds of miles on foot, the Choctaws changed into their finest clothes to greet their friends and family members who had made the journey the year before.20 For the survivors, the reunification was a moment of joy in a season of suffering.

During his trip to Indian Territory in October 1832, Isaac McCoy had seen only promise; in his rapturous imagination, native peoples were following “the path for their deliverance.” But his optimism was unwarranted. In the spring of 1833, only a few months after the arrival of the cholera-ridden Choctaws, those who had journeyed west the year before ran out of food. The first migrants had arrived too late in the season to clear fields and plant crops, and now, as the weather warmed, their twelve months of government-supplied provisions had come to an end. They scavenged for carrion and retrieved and ate the carcass of a diseased cow that was putrefying in the spring heat. The disbursing agent, a young West Point graduate named Gabriel J. Rains, suggested that he could give them condemned pork. The Choctaws had refused it once before as a part of their rations, but now, he correctly surmised, they would be glad to have it. The meat, which was six or seven years old, was not putrid or spoiled, he hastened to add, “except by age and salt.” In distant Washington City, the commissary general’s office noted that the starvation of the dispossessed was “much to be lamented,” but these bureaucrats lacked the power and motivation to do anything, beyond issuing condemned pork.21

The situation turned from bad to worse as the summer began. In the first week of June 1833, a catastrophic flood of the Arkansas River destroyed the Choctaws’ newly established corn fields, swept away their recently built houses, and destroyed the government corncribs. Cholera and malaria took hold in the stagnant water, and when F.W. Armstrong visited that fall, he was shocked to see so many dead and dying people. “Will the Government suffer them to die for want of a little medicine,” he asked the commissioner of Indian Affairs. The usually frugal officer volunteered to purchase the medical supplies himself, if the federal government would not approve the expense. A few months later, he all but begged the War Department to provide for the starving families. George Gibson held firm. “This is a disagreeable state of things,” Gibson wrote, “and I wish there were any way in which to remedy it.” He had no authority to issue more than a year of rations to the Choctaws, he explained, closing the letter with a bit of moralizing: “I wish that everything may be done to influence them to self-reliance, and not to a dependence on the bounty of the Government.” The disbursing agent Gabriel Rains reassured the commissary general that those who were not cultivating crops would be “let to starve.”22

By one estimate, about 20 percent of the Choctaws in the West died in the fall of 1833. The death toll among Creeks who had migrated appeared to parallel this precipitous decline. Most Creeks still remained in their eastern homelands, but about 3,000 had moved west in small parties over the previous few years. Of these, there were only 2,459 survivors by the end of 1833. According to one officer, after the flood not more than a quarter of the Creek children born between 1830 and 1833 were still alive.23

~~~

TO THE north, three indigenous communities were also on the move during the cholera times. The Shawnees of Wapakoneta, the Odawas, and a mixed band of Senecas and Shawnees from Lewistown—numbering eight hundred in all—were expelled from their homelands in western Ohio in September 1832. The operation was chaotic from the outset. The secretary of war insisted for months that “the plan of removal” by steamboat was “unalterable,” even as the Shawnees refused to consider traveling by any means but horseback. Elderly women were especially resolute, maintaining that they would prefer to die in Ohio and be buried with their relatives rather than board a steamboat. They were clear-sighted about the matter. “It will [be] but a short time before we leave this world at any rate,” they said; “let us avert from our heads as much unnecessary pain and sorrow as possible.” Andrew Jackson finally relented—a rare example of Old Hickory bowing under the relentless pressure of elderly Shawnee women—but his belated decision delayed the day of departure. Likewise, though the dispossessed had requested smallpox vaccinations, the medicine arrived late and was apparently useless. The federal government also failed to deliver promised blankets, rifles, and money on time.24

By one account, the supervising officer James Gardiner was “swelled like a toad” with pride in his government position, though his name was “a jest upon the road.” An alcoholic, he once fell drunk from his horse and was carted home sprawled atop a wagonload of corn. The disbursing officer John F. Lane was perhaps more sober, but his self-restraint extended only so far, for he was said to be involved in “a settled plan of extortion” to profit from the operation, even inventing the position of “Disbursing Assistant’s Clerk” for his younger brother. Lane, a vain young man of twenty-two years, became an object of derision when he made a “flowery” speech to the Shawnees, urging them to follow the War Department’s route west rather than their preferred, more direct route. By the U.S. route, he advertised, “they would get to see several fine towns, fine houses and farms on the road, as well as many white people.” The Shawnee leaders returned to the conference the next day and proceeded with formal greetings and pipe-smoking. Wayweleapy, a Shawnee elder renowned for his stately speeches, then stood up and turned to Lane: “My friend, we, the chiefs, are old men. . . . Tell the President, we don’t do business with boys.” Natives and newcomers alike erupted in laughter, a humiliating moment for Lane that momentarily eased the Shawnees’ frustration with the callow West Point graduate, who neither spoke their language nor knew anything about them.25

The Shawnees’ departure could not take place before the Feast of the Dead, customarily performed before abandoning a village to memorialize and perpetuate the memory of deceased relatives. Told to hurry up—they were in danger of “offending” the president, who “was paying large sums of money every day for their comfort and convenience in moveing to their new homes”—they ignored the request. They would be ready after their “religious duty” was performed, and not before. Federal officers bided their time by distributing blankets, guns, and tents, and auctioning the property of the dispossessed to U.S. citizens. Meanwhile, the Shawnees and Senecas secured the release of a relative who was imprisoned in the state penitentiary.26 Finally, in late September 1832, they set out from Ohio on their journey west.

The refugees soon became an object of curiosity for U.S. citizens, who visited the nightly camps to sell alcohol and to gawk at their “tawney brethren.” The peddlers of alcohol were “miserable and mean wretches,” complained Gardiner, who blamed them for bringing “disorder, mutiny, and distraction” into the camps. At a time when the American Temperance Society was the single largest reform organization in the nation, these men were easy to condemn, but the spectators who gathered merely to lay eyes on Indians one final time were in their own way also shameless. They were sightseers rather than witnesses, there to celebrate the disappearance of the region’s native residents. On one occasion, one of the refugees participated in a ruse to drive off the visitors by delivering a loud speech in his indigenous language, which was mock-translated as a threat that armed warriors would soon take up positions in the camp. The crowd quickly dispersed.27

By the time the refugees crossed into Indiana, barely a week into the journey, Lane, in his role as disbursing agent, had already exhausted the limited government funds, leaving the operation without means to purchase food, supplies, and fodder. In a letter to Cass, Gardiner underscored the absurd and bitter irony of the situation, reporting that over the past month the expulsion had been supported by money “borrowed from the Indians themselves.” Meanwhile, Gardiner’s clerk and nephew confessed—in a letter not seen by Cass—that the federal agents had been living better than ever. Throughout the fall, he had found the weather beautiful, the views “romantic” and “sublime”—and the tavern bills “immoderately, extravagantly high.”28

In early October, as they headed past Indianapolis, word reached the refugees that cholera had appeared in St. Louis, the busy river port on the Mississippi that then boasted a population of six thousand. “Keep cool” and “trust in Providence,” advised the St. Louis Republican, assuring its readers that mortality was confined to “persons of intemperate habits” and “people of color.” About two hundred individuals, or 3 percent of city residents, would die from the disease. As residents fled the city, federal officials prevented them from entering the refugee encampments for fear of contamination.29 Skirting to the north of the deserted river port and its cholera-infested streets, the Odawas and Shawnees of Wapakoneta crossed the Mississippi near the city of Alton, Illinois. From there, they would march due west to their destination in Kansas. Meanwhile, the Shawnees and Senecas of Lewistown circled St. Louis to the south and then set out southwest, heading for the northeastern corner of what would become Oklahoma.

It is not clear when V. cholerae struck the Odawas and Shawnees of Wapakoneta. Though several of their children had died reportedly from cholera, dysentery, and other illnesses before reaching the Mississippi, the true causes of death are uncertain. On November 5, a few days after crossing the great river, an Odawa was found sick by the roadside, in terrible pain and begging for water. He survived at least until the next day, but four others died shortly after. One federal agent denied that the microbe was circulating among the deportees, but like his fellow officers, he had scant medical knowledge and just as little reason to identify the disease when he saw it, given the panic that would ensue. As the train of refugees crossed through Missouri, fearful residents slammed their doors, peeking out windows to catch a glimpse of the weary travelers. It was now late November, and the weather turned to snow and ice, mercifully halting the spread of V. cholerae but producing its own hardships. Setting up camp after dark in frigid temperatures, the shivering refugees struggled to find a spot to stretch their tents over the snow and build a fire. The children “wept bitterly” in the frigid weather, wrote one officer, and some of them nearly froze to death.30

The Shawnees of Wapakoneta and Odawas arrived in eastern Kansas seventy days after their departure from Ohio, while the Shawnees and Senecas of Lewistown arrived in northeastern Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) two weeks later. The road had been filled with obstacles. The United States failed to deliver supplies on time. Peddlers plied the refugees with alcohol along the way. The disbursing officer ran out of funds. Cholera struck at least a part of the group. And the weather turned dangerously cold. Despite the difficulties, there were moments of relief, if not pleasure. On one occasion, a refugee took out a fiddle, and a mixed crowd of white men, Senecas, and Shawnees danced together, a scene that was repeated more than once. On another, the refugees stayed up late telling amusing stories. The assistant conductor went to bed that night “laughing a good deal” at “Indian wit,” which, he noted, “was indeed good.”31

When the operation was over, officers reported that they had successfully completed their assignment, but the numbers tell a different story. Some 808 people had departed Ohio in late September, but only 626 arrived at their destination, an attrition rate of over 20 percent. Though the sources indicate that a few had died on the road, there is no record of what happened to the vast majority of the 182 people who had disappeared. One officer explained the discrepancy by referring vaguely to “various changes made during the route.”32 Whether the missing people died or slipped away is unknown.

~~~

THE CHOLERA times posed no great challenge to the fiction that native peoples were leaving their homes voluntarily. Many Americans in the East were too busy speculating in indigenous lands to care much about what had happened to the original residents. As far as their curiosity and conscience prompted them to wonder, they told themselves that the United States had embarked on a humanitarian enterprise to remove Indians. How and where the Indians were sent did not much trouble them. As for the U.S.-Sauk War of 1832, many U.S. citizens thought that the attacks waged by Sauk partisans justified calls for their extermination. One U.S. Indian agent detailed the atrocities. Sauks reportedly cut out the hearts and severed the limbs of U.S. soldiers on the battlefield, and they mutilated American citizens “beyond the reach of modest description.” White women were “hung by their feet,” wrote the agent, and “the most revolting acts of outrage and indecency practiced upon their bodies,” while the children were “literally chopped to pieces.” The United States, he concluded, should expel the Sauks “with every indignity”; it should “spew them out of its mouth.” 33

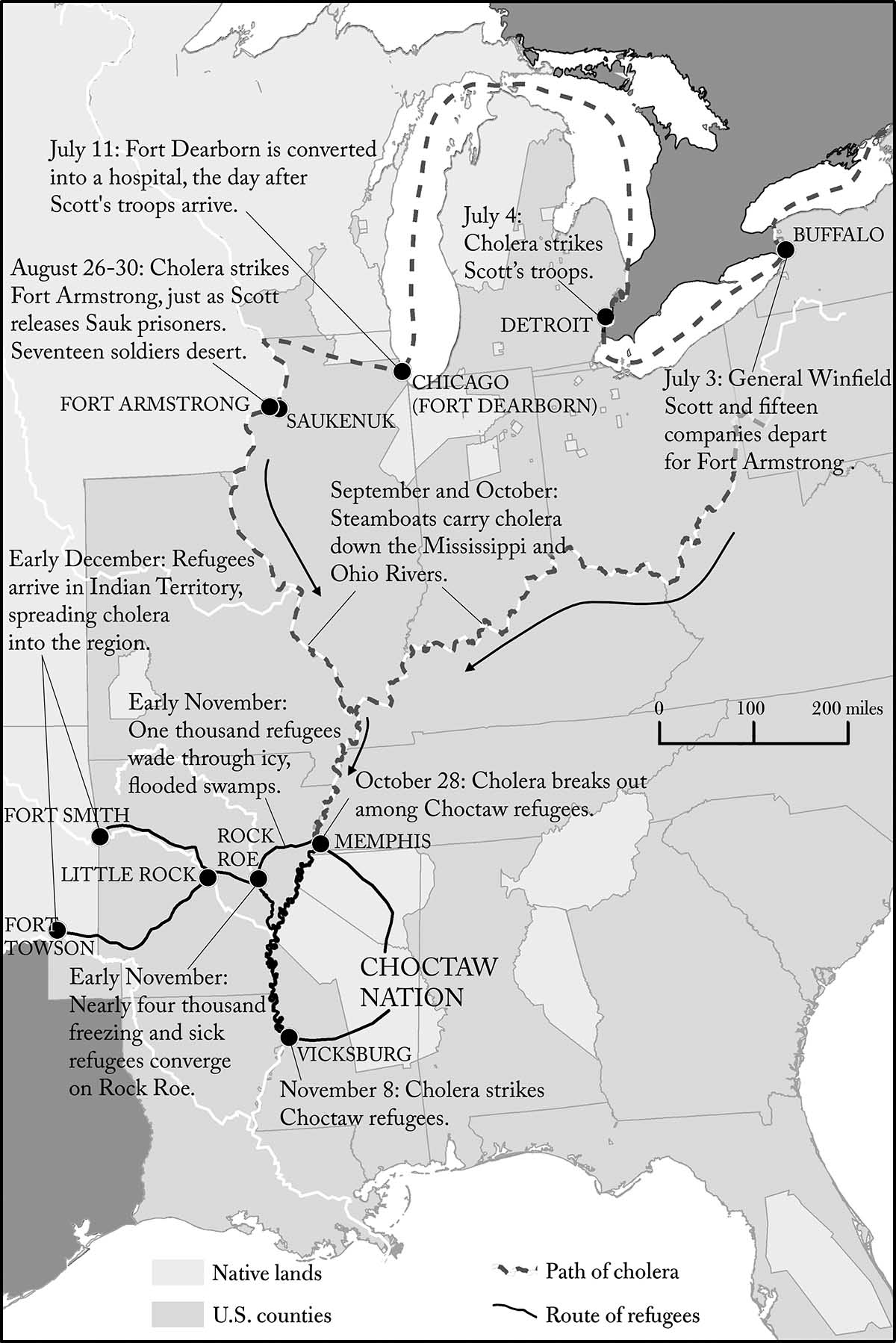

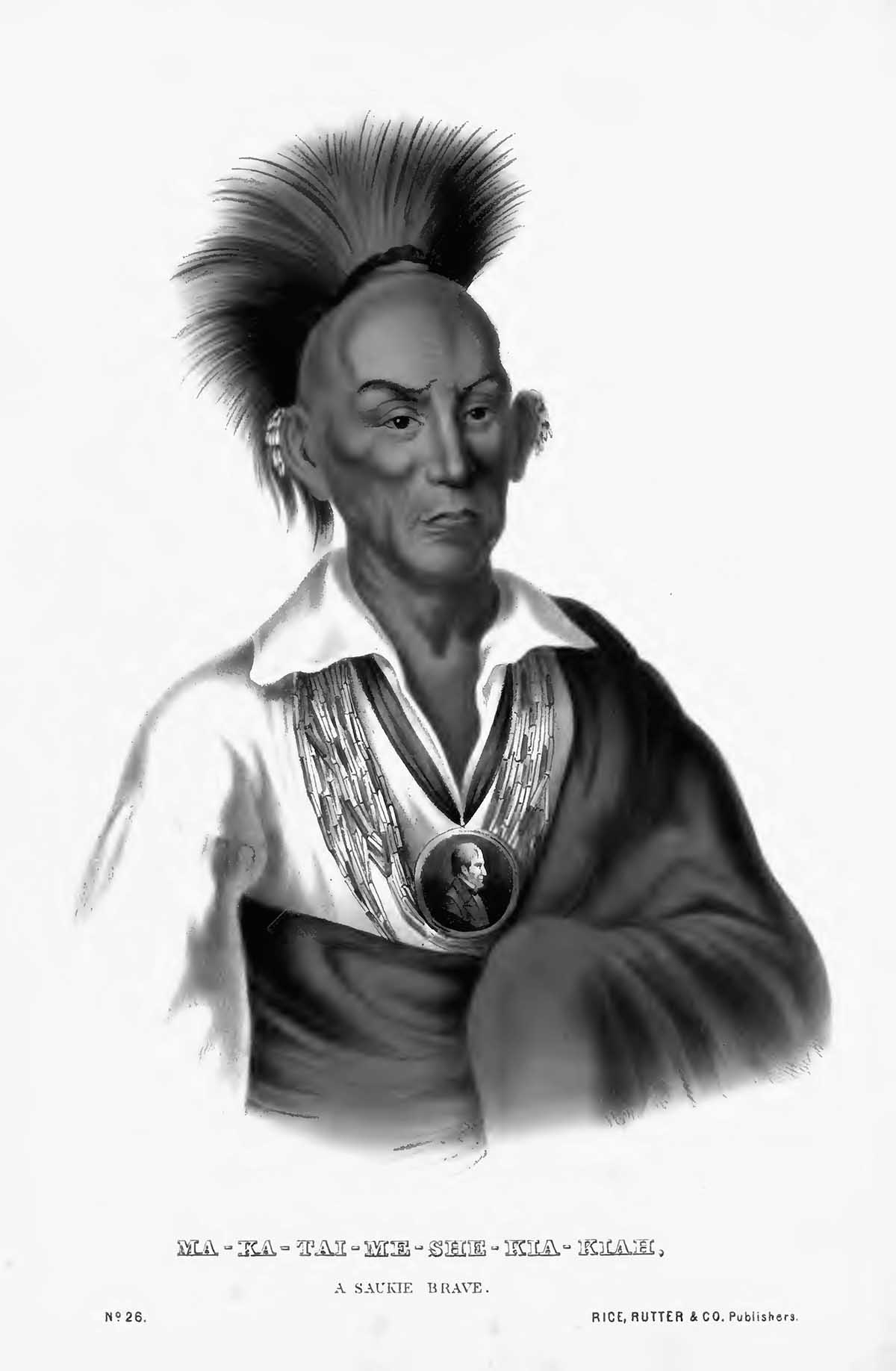

There was, however, another challenge to the expulsion of indigenous Americans that proved to be more difficult for U.S. citizens to reconcile with their self-image. While the Sauk leader Black Hawk went to war, his Cherokee counterpart John Ross went to court. Black Hawk was a generation older than Ross, but their distinct approaches resulted largely from their upbringing, not their age. Ross grew up surrounded by English speakers and, aided by private tutors, learned to read and write in English as a young boy. While Ross was mastering cursive script, Black Hawk killed his first man and triumphantly returned to his father with the scalp. As a result of these contrasting childhoods, Black Hawk knew far more about warfare than Ross did but had little understanding of U.S. politics. The differences between the two men only continued to widen. Ross visited Washington City and participated in negotiations with the U.S. president for the first time in 1816, when he was all of twenty-six years old; Black Hawk would not do so until the close of the U.S.-Sauk War of 1832, when he was in his mid-sixties. Even after the eye-opening trip, he would continue to refer to U.S. army officers as “war chiefs,” as his words were translated into English. When the expulsion crisis approached, it is not surprising that Black Hawk consulted with a prophet, while Ross retained a lawyer. The Sauk leader—said to be “of undoubted bravery” but “ferocious, cruel and vengeful”—was in many ways a more comforting figure to white Americans, who expected their Indians to sport a Mohawk, wear earrings, and pick up a tomahawk when angry. By contrast, Ross, dressed neatly in a waistcoat, tailcoat, and bow tie, waged what his fellow Cherokee John Ridge called “intellectual warfare.”34 For the U.S. government, Ross would prove the more formidable opponent.

Black Hawk in 1837 at age seventy, a year before his death.

John Ross in 1835 at age forty-five.

After the equivocal decision in The Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia, Ross and William Wirt sought out another case that might resolve the question of the Cherokee Nation’s relationship to the state. They were handed one by the Georgia Guard, a band of some forty men organized by the state in 1830 to patrol the Cherokee Nation. The Guard resembled a paramilitary organization more than a police force, as Elias Boudinot, the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, observed, for it operated with little legal restraint. In the summer of 1831, the Guard arrested eleven missionaries for violating a state law that required white people residing within the Cherokee Nation to take an oath to support and defend the constitution and laws of Georgia. The missionaries were tried and convicted in a state superior court and sentenced to four years of hard labor at the state penitentiary. All but two of them, Samuel Worcester and Elizur Butler, pledged not to violate the law again and accepted a pardon from the governor, who was eager to forestall a legal challenge to state authority over the Cherokees. The two holdouts, guided by Ross and Wirt, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Since the “domestic dependent nation” that Ross governed was not a party to Worcester v. Georgia, as the case is known, the Supreme Court had clear jurisdiction. The court would finally determine whether the extension of state sovereignty over the Cherokee Nation violated the U.S. Constitution, U.S.-Cherokee treaties, and U.S. law.35

Wirt and his law partner John Sergeant argued the case before the court in late February 1832. The Cherokees, Sergeant asserted, were “a State—a community.” “Within their territory,” he continued, “they possess the powers of self-government.” Moreover, their rights were guaranteed by treaties, which remained the “Supreme law of the Land” and were superior to the laws of Georgia. The assertion that the treaties were somehow not treaties was “without the slightest foundation.” Sergeant’s argument was not particularly original, for the Cherokees had made it often on the pages of the Cherokee Phoenix and had presented it to Congress in two separate memorials in 1830. Sergeant concluded by quoting Chief Justice John Marshall’s own language from The Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia. “Indian tribes,” Marshall had said, were “domestic, dependent nations” and in “a state of pupilage.” Their relation with the United States, he had declared, resembled “that of a ward to a guardian.”36 But what sovereign rights did they retain as “domestic, dependent nations”? Knowing that Marshall was sympathetic to the Cherokees’ cause, Sergeant now invited the chief justice to elaborate on the paternalistic metaphor he had formulated in the previous year.

Writing for the majority, Marshall handed down the decision on March 3, 1832. “The Indian nations,” he allowed, “had always been considered as distinct, independent political communities, retaining their original natural rights, as the undisputed possessors of the soil, from time immemorial.” They were the “weaker power,” he admitted, but in associating themselves with the stronger, they had not surrendered their independence. Rather, the Cherokee Nation occupied its own territory in which the laws of Georgia had no force, and Georgia citizens had no right to enter without permission from the Cherokees themselves. Georgia’s laws targeting the Cherokees, he declared, were “repugnant to the constitution, laws, and treaties of the United States.”37

Cherokees greeted the decision with jubilation. “It was trumpeted forth among the Indians,” reported one federal agent, who was dismayed by the “rejoicing, yelling and whooping in every direction.” “It is glorious news,” celebrated Elias Boudinot from Boston, where he was on a speaking tour with John Ridge. “The question is for ever settled as to who is right and who is wrong,” he wrote, observing that the struggle was now between the federal government and the State of Georgia. Ridge, for his part, described the victory as a rebirth. “Since the decision of the Supreme Court,” he wrote, “I feel greatly revived—a new man and I feel independent.”38

Worcester v. Georgia represented a complete legal victory for the Cherokees, but the consequences were far from clear. “We shall see how strong the links are to the chain that connect [sic] the states to the Federal Union,” Ridge observed. Two days after Marshall handed down his stunning decision, John Quincy Adams, four years past his presidency and now serving as a representative from Massachusetts, introduced a petition to the House from the citizens of New York City asking Congress to “enforce the observance of the laws of the Union” and “vindicate the constitutional authority of the Federal Government” by protecting the Cherokee Nation. The memorial touched off a fiery debate. Representative Augustin Clayton of Georgia, who as a state judge two years earlier had sentenced the Cherokee George Tassel to death, took the floor to proclaim that Marshall’s decision would not be executed “till Georgia was made a howling wilderness.” His state, he warned, “only wanted the application of a match to blow the Union into ten thousand fragments.” Would the House provide the spark, he asked, that would “rend the Union to pieces?”39

Clayton’s attack on New York’s memorial was a thinly veiled defense of the prerogatives of slaveholders. He outlined for his fellow representatives the horrors that Cherokee independence brought to the Deep South. A white man had rented a horse from the Cherokees, he recounted, and accidentally traveled farther than agreed. The Cherokees accused him of theft, suspended him from the limb of a tree, and whipped him fifty times as he begged for mercy. “The savages,” Clayton charged, “were perfectly inexorable.” Without the extension of Georgia sovereignty, he warned, such incidents would multiply.40

In fact, the events surrounding Clayton’s anecdote were quite different. The accused horse thief had been put on trial before a jury of Cherokees in the Cherokee Nation and convicted and punished according to Cherokee law. Summary judgment and arbitrary punishment were hallmarks of Clayton’s home state, not the Cherokee Nation. The “dreadfully savage” Thomas Stevens, for example, severely flogged John Brown on numerous occasions. The crime? Stevens, a white planter who had recently purchased Brown and separated the young boy from his parents, objected that his new slave labored indifferently in the cotton fields. On one occasion, Stevens nearly beat Brown to death for not running fast enough to retrieve a key. Brown was saved when a neighboring planter rode up and announced that a “drove of negroes” had arrived from Virginia, prompting Stevens to drop his whip and hurry off to have “the pick of them.” On another, as Brown was kneeling to fix a broken plow, Stevens kicked him between the eyes with all his might, breaking his nose, dislocating one eye, and permanently damaging his vision. The slave owner “became so savage to me,” recalled Brown, “I used to dread to see him coming.” Perhaps even more horrifying were the medical experiments that a neighboring doctor was permitted to perform on Brown. They included exposure to extreme temperatures (to measure the effect of heatstroke), bloodletting (purpose unknown), incisions (to determine the depth of skin pigmentation), and other procedures, “which,” Brown painfully acknowledged, “I cannot dwell upon.” 41

Clayton and his fellow planters did not concern themselves with such crimes, however, because the extension of Georgia sovereignty, in their minds, ensured the rights of white people to rule over others, not the rights of their would-be inferiors. Worcester v. Georgia had become a proxy for white supremacy. As John Ross and other Cherokees anxiously looked on, the slave society that had grown up around them and that had corrupted their own communities—for they too now had plantations—denounced the Worcester decision as passionately as it defended slavery. Not far from the site of Brown’s brutal treatment, the white men of Jones County in central Georgia resolved that the court’s decision jeopardized “the perpetuity of the Union”—a dire threat that would be heard repeatedly in coming years. Similar declarations rang throughout the state. Marshall’s opinion was “a palpable and dangerous invasion of rights,” said the white men of Taliaferro County, seventy-five miles east of Atlanta. “Georgia,” they asserted, “has ever had the right to subject every class of her population to her laws.” In Burke County, just south of Augusta, white men resolved to defend their “rights and interests” against the Supreme Court’s “arbitrary assumptions of power.” And in Gwinnett County, bordering the Cherokee Nation, the aggrieved citizens complained that northerners were intermeddling with their “local concerns” by slandering them on the subject of two “troublesome” populations, Indians and slaves. Marshall’s decision was “not binding on the people of Georgia,” they said, vowing to support state authorities “to repel all invasions on their Jurisdiction.”42

Ross was besieged by advice from would-be allies who urged him to sign a treaty agreeing to expulsion. The Cherokees’ situation had become “perilous,” reported one federal agent, who delighted that the longtime inhabitants would soon be compelled to move west. A few had already registered to be deported, and the United States recruited white volunteers to surround their temporary encampment to prevent them from escaping before the departure. One letter arrived from Supreme Court justice John McLean, who had joined the majority in Worcester v. Georgia. Motivated, he claimed, by “a deep solicitude” for the Cherokees’ prosperity, he counseled them to move west. It was true that the 1802 Trade and Intercourse Act forbade U.S. citizens from crossing into Indian territory, he wrote, but since Cherokee lands were held in common, individual Cherokees could not sue for trespass. Nor could the nation as a whole take legal action. As The Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia had made clear in 1831, it had no standing as a foreign state before the Supreme Court. “The cases are very few where the Courts of the United States can take jurisdiction, in the assertion of any rights which you may claim,” Justice McLean explained. “You can judge, how inadequate a remedy must be for your nation, which is limited to a very few cases, involving individual rights, and prosecuted at a heavy expense.” Whatever his motivation, McLean’s legal point was true enough, for it was widely held that the Bill of Rights limited the actions of only the federal government, not the individual states. Most jurists agreed that Georgia was free to oppress African Americans and Native Americans with impunity.43

Elisha Chester, Worcester’s one-time attorney in Georgia, also offered his unwanted counsel to Ross, warning that the “evils . . . are hourly increasing.” Chester insisted to the Cherokee leader that there was “not the remotest prospect of relief” for his people in their present location. But he was hardly a disinterested observer. The attorney, after working on behalf of the Cherokee Nation, had unscrupulously accepted employment as a special agent for the United States. He advised Secretary of War Cass to give no relief to the Cherokees from the “pressing evils” that surrounded them.44

In the fall of 1832, the Cherokees’ troubles multiplied further. After the legislature authorized the appropriation of Cherokee lands in December 1831, surveyors had run chains in every direction in the Cherokee Nation, crisscrossing family farms and bisecting native villages. They completed the surveys in September 1832. For a nominal fee, any state citizen could now purchase a chance to own a piece of the Cherokee homeland, as long as he or she was white and not a resident of the Cherokee Nation. Finally, with great fanfare state officials drew lottery tickets at random from great revolving drums and announced the names of 53,000 lucky winners. This horde of fortunate stub holders lost no time in rushing into the nation to stake their claims, driving off the native residents by lash if necessary.45 The state would distribute over 4.28 million acres of Cherokee land this way.

As the fate of Worcester v. Georgia hung in the balance in late 1832, Georgia politicians received a gift. The Nullification movement in South Carolina reached a climax, propelled by a series of alarming events that had brought slaveholders to the barricades. In January 1831, William Lloyd Garrison had launched his abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. Eight months later, Nat Turner had organized a slave uprising in Southampton County, Virginia. Soon afterward, the Virginia legislature had taken up the question of abolition. And Congress was once again debating whether or not to fund the American Colonization Society. Slavery itself seemed to be under attack, galvanizing South Carolina politicians to insist on their right to nullify national laws that might challenge their hegemony. The immediate cause of their protest was a federal tariff, but the true value of nullification was not in the savings on tax-free pig iron, roofing slates, and woolen goods—though the financial benefits would be significant—but in the peace of mind that they were the unquestioned masters over their human property, the more than two million slaves, valued at nearly $700 million, who were laboring in the South. With the right of nullification, the region’s “domestick institutions,” as John C. Calhoun put it, would remain forever safe from “Colonization and other schemes” dreamed up by fanatics in the North.46

If Georgia joined South Carolina in nullification, thereby fusing the movements against Worcester v. Georgia and the federal tariff, the integrity of the Union would be in danger. Quietly, politicians worked behind the scenes to separate the states’ two causes. Stephen Van Rensselaer, president of the Missionary Society of the Dutch Reformed Church and one of New York City’s wealthiest men, appealed directly to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, urging Worcester and Butler’s home organization to concede the legal battle to Georgia. Simultaneously, Georgia’s governor expressed his keen desire to issue a pardon to the two missionaries. The campaign was a success. In February 1833, the missionaries capitulated, writing to Governor Lumpkin that they would accept a pardon, and Georgia, in turn, rejected South Carolina’s invitation to join the Nullification movement.47

By the spring of 1833, it had become clear that Jackson would not enforce the Supreme Court’s decision. In response, Boudinot, Ridge, and several other native leaders despaired of the Cherokees’ future in the East and began urging their people to sign a treaty with the United States. Although they were (and still are) accused of having betrayed the nation, their capitulation reveals less about their personal integrity than it does about the unremitting persecution that the nation faced. Ross, however, held firm. “Let us still patiently endure our oppressions,” he exhorted, “and place our trust under the guidance of a Benignant Providence.” 48

~~~

IN A public meeting in late March 1832, the citizens of Columbus, Georgia, appointed a committee of men of “distinguished character and moderation” to draft a statement of opposition to Worcester v. Georgia. “It is, indeed, felicitous that, upon a question embracing the vital interests of Georgia, her citizens are speaking as with one voice,” wrote the Columbus Enquirer, for “the spirit of the times requires united counsels and united movements.” Founded only four years earlier, Columbus sat at the fall line of the Chattahoochee River, the northernmost point of navigation for steamboats coming upstream from Apalachicola and the Gulf of Mexico. The city’s boosters projected that it would come to dominate interior trade, though their high hopes would later be dashed by the arrival of railroads, which carried cotton directly to the Atlantic Coast, bypassing the river port. By the time of Marshall’s decision, Columbus boasted a population of 1,800, about 40 percent of whom were enslaved. “Well done, Columbus!” exclaimed the local newspaper; “Four years ago a howling wilderness; now a handsome town.” The river had not yet become polluted with sewage and runoff from cotton plantations, and in the spring, Creek families still fished for shad in its waters, using nets fashioned out of strips of bark. Creeks regularly visited by the hundreds and sometimes thousands, doubling the town’s population, but, recalled an early resident, they were not permitted to stay overnight on the Georgia side of the river. No southern inland town had progressed with “more rapidity,” crowed one Columbus denizen. Nonetheless, its eminent residents were hardly distinguished by national standards, and the committee to draft the statement on Worcester v. Georgia was composed of small-town businessmen and local politicians who possessed unbounded ambition and parochial views. It is not surprising that Eli Shorter was among them.49

“Among the proud intellects of Georgia, . . . none was more commanding, none more transparent, none more vigorous and subtle in analysis, than that of the Hon. Eli S. Shorter,” wrote an admiring biographer. Born in Georgia in 1792, Shorter was orphaned and left penniless at age five. Educated at the expense of his older brother, Shorter became a lawyer, enriched himself by specializing in debt collection, ran successfully for state superior court, and resigned in a sex scandal. He did not stay down; instead, he “cast off difficulty as a lion shakes the dew from his mane.” This overblown image—Shorter’s own—was “worthy of Napoleon,” wrote his biographer.50

Whatever his qualities, a working sense of irony was not among them. The committee’s statement on Worcester v. Georgia began by underscoring that “the dearest interest and most sacred right of freemen”—that is, self-government—was at stake. The Supreme Court ought to be respected, it continued, except when its decisions deprived states of “the power of making laws for their own government.” In such cases, it was “the duty of the people” to “protect and defend” their sovereignty. The choice before the citizens of Georgia was stark—submit as slaves, or resist and defend their freedom. They had inherited their freedom from their fathers, the committee proclaimed; they would just as surely bequeath it to their children. It seems not to have occurred to Shorter and his fellow committee members that, in defense of self-government, native peoples had the stronger claim. Where their fathers had “formerly walked without restraint,” Creeks petitioned Congress, they were now “hemmed in” and “condemned to slavery.”51

In his frequent high-minded and self-pitying protestations, Shorter often failed to see the irony. The tariff that triggered the Nullification crisis, he charged, was a “system of oppression and plunder.” To surrender, the owner of seventeen slaves wrote, would be to “meekly submit our necks to the galling yoke of our oppressors.” A few years later, he objected to permitting native peoples to testify when their own interests were at stake, though he took for granted his own right to do so. How could Native Americans be trusted, he asked. It galled him that the federal government accepted “the bare-naked statements of Indians.” “What have we done which is to deprive us of the protection of the laws of our country?” he pleaded, suggesting to Secretary of War Cass that “We may have the misfortune of bearing your deep-rooted prejudices.” Creeks of course had asked the same question many times. In Shorter’s prose, imitation was not a form of flattery. In all sincerity, or with complete cynicism, the colonizer and slaveholder insisted that he was “scrupulously regardful of the rights of others.”52

In brief, Shorter’s sense of entitlement and aggrievement, like that of most elite white southerners, knew no bounds. He felt particularly entitled to the native lands that lay across the Chattahoochee River from his Columbus residence and especially aggrieved that Creek families still lived on them. Casting an eye on the rich soils of the Creek Nation, he and other ambitious Georgians set about dispossessing the region’s longtime residents.