“A COMBINATION OF DESIGNING SPECULATORS”

~~~

NEW YORKERS considered J.D. Beers to be one of Manhattan’s eminent residents, a “high-toned Episcopalian” and talented businessman who owned some of the city’s most valuable real estate, including three properties on Union Square and a lot in midtown that would later become the site of Radio City Music Hall. He was, said a family member, “a consistent Christian in his walk and conversation.” Likewise, in Columbus, Georgia, Eli Shorter, despite a somewhat checkered past, enjoyed a “distinguished” reputation as a local dignitary and member of the bar. A fellow lawyer called him “a man of a century.”1

In the Creek Nation, however, residents despised these two outsiders. Beers and Shorter were among the most rapacious of the “merciless horde” that haunted Opothle Yoholo’s homeland. “The homes which have been rendered valuable by the labor of our hands,” the Creek leader protested, “are torn from us by a combination of designing speculators,” who were “so fierce” that no one could pass by them and so relentless in their pursuit of Creek lands that it was as if they were possessed by demons. “The helpless widow and orphan, the aged and infirm father,” he continued, “are alike the victims of their cupidity.” Opothle Yoholo drew his imagery from a passage in the Book of Mark that is often read as an anticolonial parable in which colonizers are akin to demons. In the Creek leader’s retelling, the United States resembled imperial Rome and its occupying army the Roman legion. He was not alone in finding that the speculative fever of the late 1830s resembled a sort of diabolical possession, for some U.S. citizens attributed the overheated market to “mesmeric influence.” The speculators were “ravenous,” said one U.S. official, “carrying every thing before them” and “devouring the carcass.” 2

There was indeed something ghoulish about the speculators who rushed to possess native farms before the hearths had cooled and who preyed on starving families during their final desperate months in the South. They stole not only fields, houses, and corncribs but also, as Opothle Yoholo stated, the dead. “Beneath the soil which we inhabit,” he said, “lie the pail remnants of what heretofore composed the bodies of our fathers and of our children our wives and our kindred.” One elderly Creek man who had lost his land said with “great bitterness” that “he would stay and die here and then the whites might have his skull for a water cup.” This was no dark fantasy, for a phrenologist had recently visited his village, dug up a number of corpses, and carried off the skulls. Several Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole crania ended up in Philadelphia in the collection of the renowned scientist Samuel George Morton, who used the skulls to argue that the “Caucasian race” was superior to all others. If the speculators were not possessed by demons, they were at least consumed by greed. The Chickasaw leader James Colbert had a word for them: “capitalists.” 3

The methods of dispossession employed by speculators differed from nation to nation but were all equally devastating. In the case of the Choctaws, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek described multiple classes of people entitled to reserves of land: Choctaws wishing to become Mississippi citizens; their children older than ten; their children younger than ten; the “Chiefs” of the Choctaw Nation; individuals who cultivated more than fifty acres; those who cultivated between thirty and fifty acres, twenty and thirty acres, twelve and twenty acres, and two and twelve acres; “certain individuals” (Colonel Robert Cole, John Pitchlynn, Ofehoma, and so on); captains; and, last and least, orphans. The number of classes, though unwieldly, was apparently insufficient, and a day after the two sides signed the treaty, they agreed to a supplement, setting aside reserves for still more individuals. Astoundingly, despite its detailed enumeration of classes, exceptions, and set-asides, the hastily negotiated treaty did not clearly account for the land not allotted to individuals, the Choctaws’ national domain, which amounted to ten million acres and represented one third of the present-day state of Mississippi. The General Land Office would undoubtedly auction this territory, but what would be done with the proceeds? Subsequent treaties with the Senecas, Shawnees, and Odawas in Ohio and the Chickasaws in Mississippi explicitly stated that native peoples would receive the funds, after deducting for various expenses. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, the first to be concluded after the passage of the expulsion act, contained no such stipulation. Not until 1886, fifty years after the fact, would the Supreme Court rule that the proceeds from the land sales belonged to the Choctaw Nation.4

The United States ignored most of the treaty’s obligations, though not the one that truly mattered to its citizens, the cession of Choctaw lands and expulsion of the longtime residents. By the government’s own admission, 1,585 Choctaw families, entitled to between two and three million acres, attempted to select reserves and become citizens of Mississippi, but thanks to the incompetence and ill will of the U.S. agent William Ward, only 143 received land, accounting for just over 140,241 acres. Under the treaty’s other categories, Choctaws who were entitled to 578,960 acres received only 193,860 acres.5

Speculators swarmed into the region. No piece of property remained beyond their grasp, not even the herds of cattle belonging to Choctaw farmers. Speculators conspired to purchase the livestock for “almost nothing,” colluding with Ward, who left his son in charge of the operation. “His sun as hee informed me is a wild Boy,” said one acquaintance, “but the Col says hee supposes hee will answer the purpose.” When Choctaws received certificates of valuation for their animals, the intruders speculated in those too. Other schemers fought to possess the people themselves, part of a ploy to provide legal services to the dispossessed in exchange for their land. One such operation “collected the Indians” on multiple occasions to catalog the people “belonging” to it. When a dispute arose over who was “entitled” to which families, one schemer “agreed to settle for his thirty two and the others settled for theirs.” Still other speculators purchased reserves directly from Choctaws for a $5 or $10 advance, promising to pay the balance, an additional $1,000 or $2,000, after the president approved the deeds, as required by treaty. By the time the Choctaws sought payment, however, speculators had bought and sold the deeds half a dozen times, and the original purchasers, indebted to the Choctaw owners, had long since disappeared.6

The greatest prize in this frenzy was the Choctaw national domain, an area the size of Massachusetts. Over the course of its first four decades, the Republic had devised a systematic and methodical procedure, overseen by the General Land Office, for auctioning public lands. Members of the federal government’s small but aspiring bureaucracy, designated as “registers,” oversaw the process from local agencies. Choctaw sales would take place in Mount Salus, Chocchuma, and Columbus, Mississippi, three insignificant crossroads that became hives of activity when the land offices were open for business. On auction day, the public crier announced the townships for sale, speculators shouted out their bids, and the winners reported to a window to file their applications. The register placed the paperwork in a box and, consulting a table of maps, placed an “S” on the corresponding tracts to signify that they had been sold. Later, the receiver accepted payment, wrote out receipts, and recorded the sum in a leather-bound volume.7

As with so much of the federal government’s operation to expel native peoples, the practice was quite different from the stipulated procedure. Applications disappeared, maps were marked in the wrong location, and sales and payment records did not correspond. Some of the errors resulted from incompetence or carelessness. The receiver at one office was usually drunk and incapacitated, while at another he was severely ill and unable to complete his paperwork. But many other errors were the product of deceit. “Fraudulent persons” gained access to the register’s maps and marked lands as sold in order to purchase the tracts at a later date during “private entry” sales, when there were no competing bidders. To thwart this particular scheme, the register at Chocchuma constructed a “confined desk,” but speculators continued to mark up the maps surreptitiously. Still other speculators bid on land, declined to complete the payment, and then, after the sale was forfeited, purchased the same tract at a lower price in private entry sales.8

The hordes of speculators devoured the majority of lands using a simpler, time-tested strategy. They colluded with one another. When the auctions opened in Mississippi in October 1833, Robert J. Walker, an ambitious lawyer and future U.S. senator, gathered speculators in a tavern a few yards from the land office and persuaded them to form the Chocchuma Land Company. Prices dropped by 30 percent the day after, the result of the lack of competing bids. Walker claimed that it was “a source of inexpressible gratification” to him that by artificially lowering prices he was protecting common white men, the sturdy farmers who had “moistened with their blood the soil of Mississippi” when defending the state against the “exulting savage.” It was true, he admitted, that in the course of his altruistic activities, he had also acquired a “considerable body of land” for himself, but, he maintained, he had no interest in profits—an assertion belied by his lifelong pursuit of wealth. Other partners were more candid. One company member and congressman boasted that he had arrived in Chocchuma without a dollar and left with $40,000 to $50,000. The company as a whole purchased at least 376 square miles, a little under 1 percent of the state.9

Across the Choctaw Nation, families fended off the marauders as best as they could, but behind each lone intruder stood a vast array of state power, beginning with local sheriffs and ending with the U.S. Army and its commander in chief, the president of the United States. Many Choctaws farmed their land under the mistaken assumption that the Indian agent William Ward had done his job, recording their names and establishing their title as required by treaty. Instead, the General Land Office auctioned their land to white farmers and planters, who arrived whip in hand to claim the property. Mingo Homa’s experience was not unusual. His community of two hundred people registered with Ward, but in 1833, U.S. agents ordered them to move west. “They said they would catch the children,” Mingo Homa recalled, “tie their legs together like pigs, and haul them off in waggons, and drive the grown people after them.” The families fled into the swamps, and a band of white men seized and imprisoned Mingo Homa. After he escaped, the Choctaws returned to their lands, only to be driven off a few years later.10

In 1837, in an effort to conciliate Choctaws and whitewash its own failures, the federal government would create the first of several commissions to investigate Ward’s dereliction of duty and compensate the dispossessed with scrip, good for purchasing public lands in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas. The scrip generated its own corrupt market. “By judicious management,” wrote one speculator, “a large amount of it, may be had at from 25 to 50 cents in the dollar.” Eventually, he surmised, the scrip could be converted into cash at 95 cents to the dollar. He would double or even triple his money.11

In the end, the scrip did little to make amends for the massive land theft. Nonetheless, federal commissioners interviewed hundreds of Choctaws and recorded numerous, harrowing stories of dispossession. The dispossessed, surrounded by a hostile, foreign population, faced two choices: seek refuge with other Choctaws on marginal lands in Mississippi or begin the dangerous journey west, perhaps penniless and alone. Immaka, a sixty-five-year-old woman, lived with her three grown children until a white man built a house near her and plowed a field right up to her front door. After he pried the boards off her house while she was living in it, she fled to “an old waste house” and survived on a small crop of corn. Oakalarcheehubbee, described as “an old grey headed man having but one eye,” stayed at home until Hiram Walker drove him out with a whip. Walker then put his fifteen slaves to work on the land. Illenowah, fifty years old, was living with his wife and three children when a white man named McCarty built a house next to him and pushed him off. Okshowenah, said to be “an old and infirm” woman, was a widow at the time of the treaty. All but one of her children had moved west, but she remained in the Choctaw Nation until a man plowed around her house and fenced her in. She fled, and in 1838 was preparing to move west. “I hardly expect she will get there,” said one relative, who commented, “She is remarkably old.”12

Dispossession could come at any moment. Elitubbee lived with his wife and eight children in the Choctaw Nation until 1835, when he returned from hunting to find that a white woman had moved into his house with her two children and plowed his land. Likewise, Abotaya, out hunting with his wife and mother-in-law, came home to find a man named Gibson in his house. So too Shokaio, an elderly widow. While she was hunting with her son, a white man dismantled her house and used the wood to make a stable and corncrib. Chepaka also returned home, in this instance from a visit to his father, and discovered that John Pyus had turned his residence into a stable. The invaders showed no mercy. Hiyocachee, ill and dying, moved nearby to be under the care of friends and family. Meanwhile, a white man took his land, dispossessing his soon-to-be widow. Ahlahubbee was visiting relatives when a white man moved into his house, leaving his “deeply distressed” family members with nothing more than the clothes on their backs. They built a house nearby but were turned out of that too. Ahlahubbee seemed “fit to cry,” said one witness.13

After riding past Peter Pitchlynn’s old stomp ground in Mississippi in August 1834, one of Pitchlynn’s relatives was thrown into “deep reflection.” The land was “as natural as ever,” he wrote, but the stomp ground, once a ceremonial and social center that was full of song and dance, was now deserted. “I see no pleasing countenance of a Choctaw or any to be seen only now and then here and yonder in places,” he observed. The patchwork of native farms had been replaced by cotton plantations, the Choctaw people by white planters and their slaves. “There is a great alteration in this part of the world since you left,” Pitchlynn learned from a different correspondent. “Was you back here you wou’d be a stranger in your native land.”14

~~~

In the Chickasaw Nation, where native residents did not have the option of remaining in Mississippi, speculators had two ways to purchase lands. They could buy directly from Chickasaws, who each received a temporary allotment of anywhere from one to four sections, depending on the size of the family (a section equaled one square mile). Or they could bid on “the residue of the Chickasaw country”—the lands not allotted—at one of the General Land Office auctions. The government agreed that it would invest the proceeds of the auctions on behalf of the Chickasaw Nation, after deducting the expenses for surveying and selling the lands and deporting the inhabitants.15

In the case of allotted lands, as James Colbert observed, speculators used “every stratagem” they could devise to prey on the Chickasaws’ “ignorance,” but their success depended less on ingenuity than on ruthlessness. In more than one way, the exchange of money for lands was skewed to favor investors. The impending expulsion obligated Chickasaws to sell quickly, within a few months’ time, and many did not fully understand the details of the treaty that controlled the sales. Most could not read the contracts they signed or comprehend legal jargon written in English. Moreover, they had no recourse when speculators disregarded laws, since the U.S. agent to the Chickasaws, Benjamin Reynolds, was happy to overlook the violations for a price. Colbert explained that the speculators paid “no more attention to the treaty than if it was a blank piece of paper.” In league with opportunistic “half breeds” (as Colbert said), speculators demanded that Chickasaws sell on the spot by signing a blank deed in exchange for a $5 or $10 advance. Reynolds, who had established a mutually profitable relationship with the land companies, often compelled native farmers to sell if they seemed hesitant. Either he deemed them incompetent and then disposed of their allotments for a fractional price, or he pronounced them to be “cholera cases,” shutting them out of sales altogether and making them “sweat,” until they agreed to a cut-rate price. Reynolds, said one critic, was “very poor” when appointed U.S. agent and “immensely rich” when he left office. The proceeds of collusion can be measured in slaves. Reynolds owned two people in 1830 and twenty-one a decade later.16

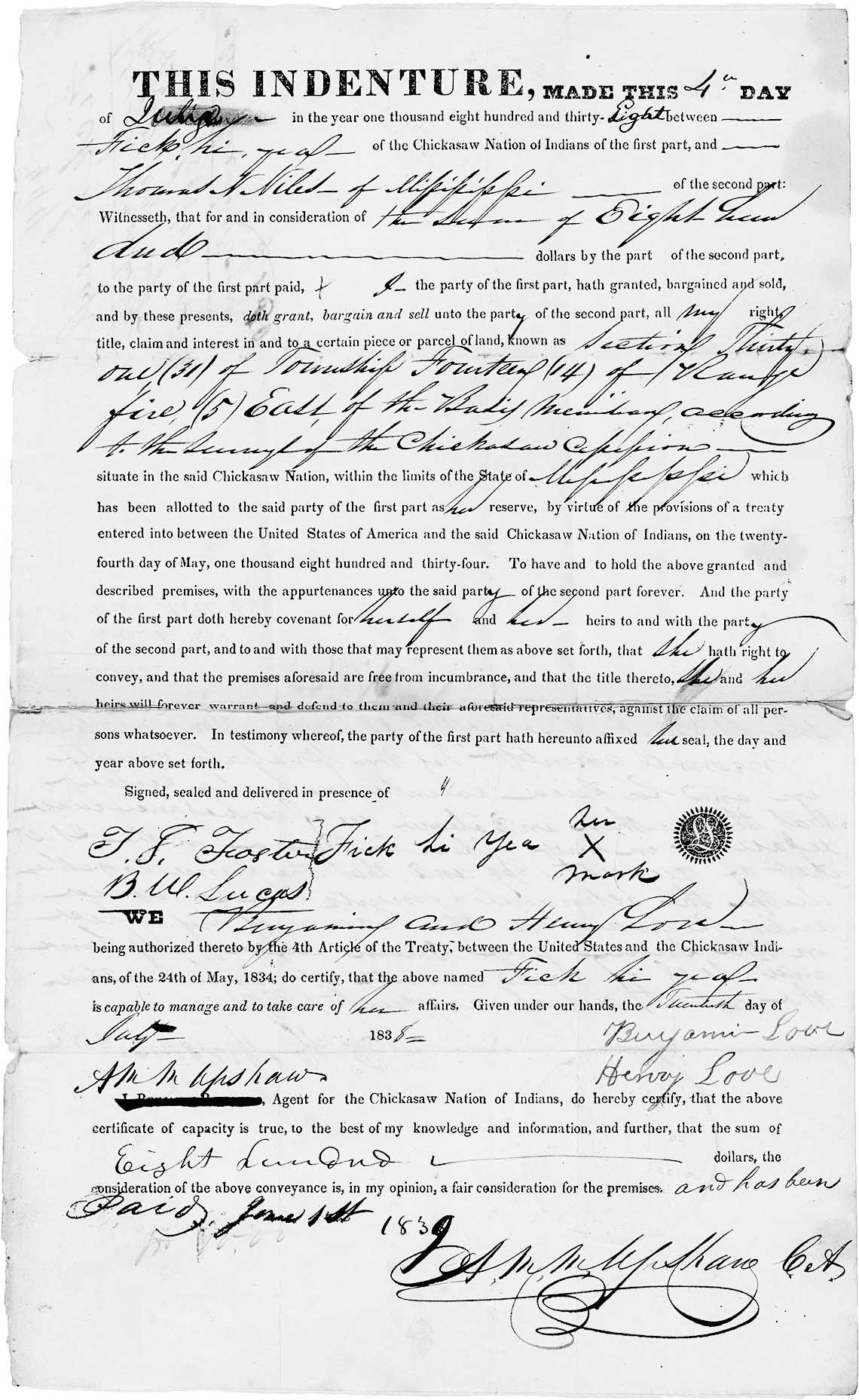

Contract between a Chickasaw woman named Fickhiyea and Thomas Niles, who speculated widely in native land. Fickhiyea sold 640 acres of Black Prairie land at the minimum price of $1.25 per acre, for a total of $800. This particular contract was never confirmed by the president.

By the calculations of the federal government, individual Chickasaws sold 3,546 square miles for a total of $3.8 million, an average price of $1.73 per acre, but the official accounting assumes that farmers received full payment rather than only the initial advance of $5 or $10. Moreover, the transactions usually involved paper money, whose exchange value fluctuated widely according to the health of the issuing bank and the national economy. (Until the United States moved to a single national currency in the 1860s, most business was conducted in regional banknotes.) When U.S. financial markets crashed in 1837, Chickasaws were left holding paper that was close to worthless. “They are incessant in their demands for specie,” complained Beers’s partner David Hubbard from Pontotoc. It was “so annoying to me,” he continued, “that I shall leave here shortly untill these poor creatures are moving west.”17

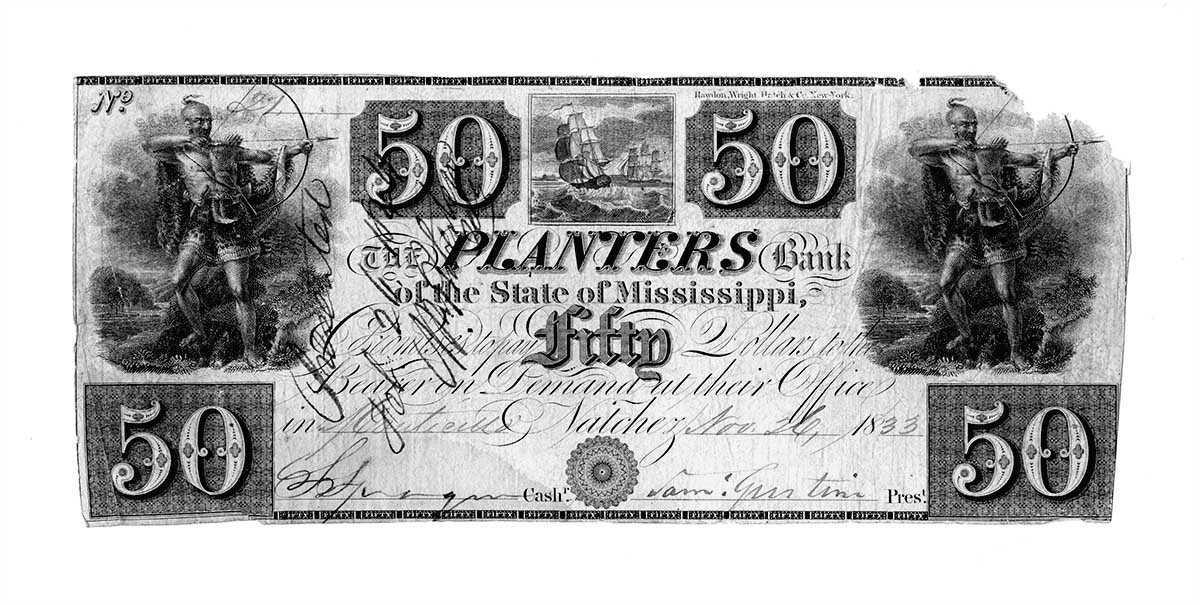

Apart from the individual sales, the General Land Office began auctioning 6,745 square miles of “residue” Chickasaw land in 1836. In Pontotoc, the site of the auctions, strangers crowded into every house within miles, and planters fought to purchase sections from the land companies. It is “speculation run mad,” said one amazed participant. Since Chickasaw leaders were aware that buyers had colluded at the Choctaw land auctions, they insisted on a treaty article requiring the president to “use his best endeavours to prevent such combinations.” The article was ineffective. The New York and Mississippi Land Company and the Boston and Mississippi Cotton Land Company had “a mutual good understanding” that was, said Richard Bolton, “essential to the interests of both.” His uncle John counseled “caution and silence” so as not to reveal the illegal arrangement, but no one was fooled. One disgusted observer described how “capitalists and companies” combined to create a monopsony (a single buyer) to force deportees to sell their lands well below market value.18

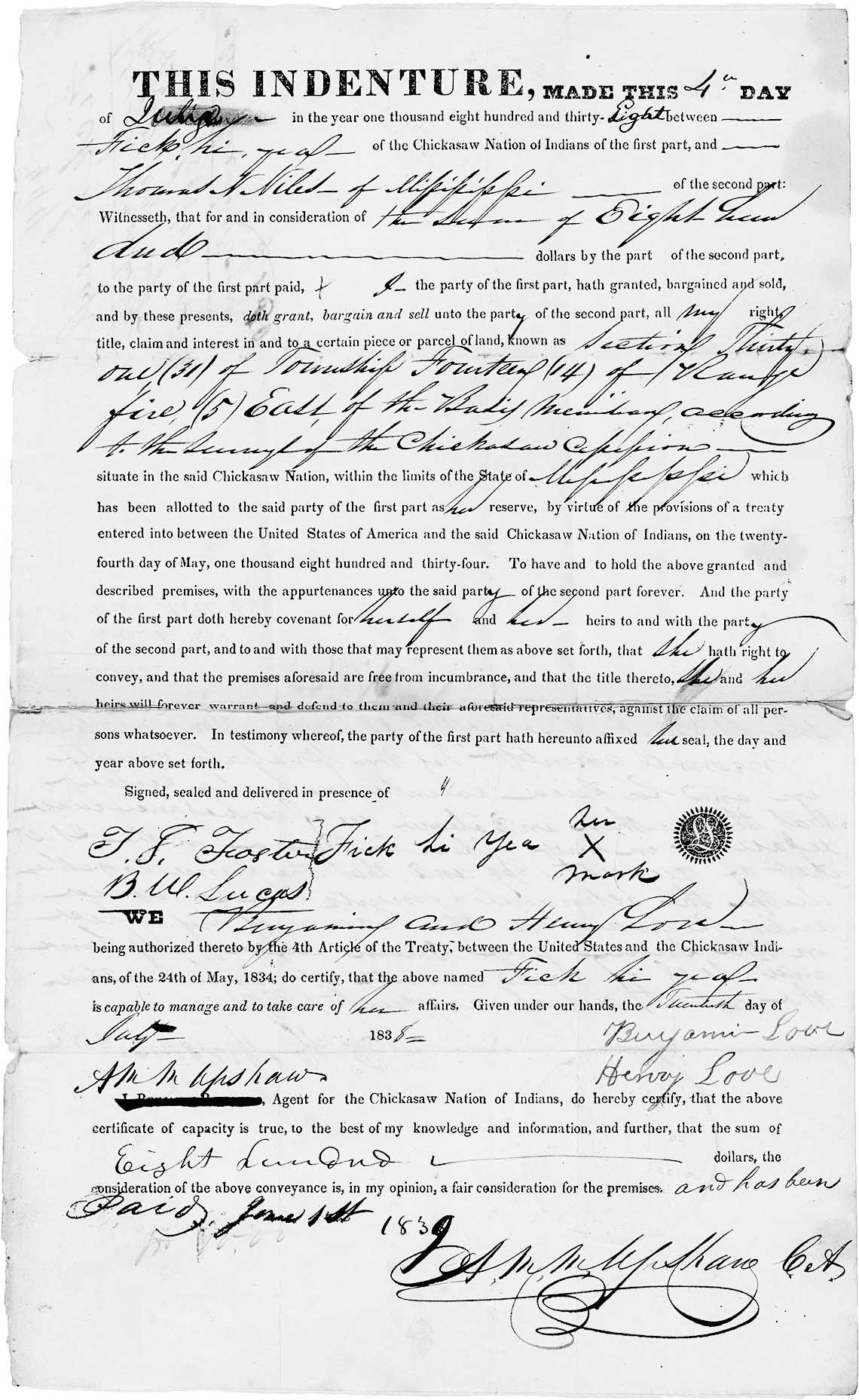

One of the depreciated bills from a bank capitalized by J.D. Beers, who sold the related state bonds in London. The bill’s artwork, featuring a stereotypical and insulting image of an Indian, encapsulates the relationship between dispossession, cupidity, and white supremacy.

The New York and Mississippi Land Company purchased 600 square miles of prime cotton lands in the Chickasaw Nation.

In the Treasury Department, an army of accountants dutifully tallied the land sales and just as dutifully deducted the expenses of deportation, which amounted to an astounding $1.2 million, or fully thirty percent of the $4,000,000 that was credited to the Chickasaw Nation. The federal government billed the Chickasaws for the census ($725), the certifying and locating of reservations ($25,735), and the dozens of clerks who were “employed in the various departments of the government on Chickasaw business” ($35,717). It billed them for 59½ pounds of nails for building storehouses on July 8, 1837; for Lieutenant G. Morris’s expenses traveling from Washington City to Fort Coffee, Arkansas, in May 1837; for camping equipment for U.S. officers engaged in Chickasaw deportation; for dressing the wounds of a Chickasaw named Uneichubby; and for postage. It billed them for the construction of desks for the U.S. agent, Benjamin Reynolds, in Pontotoc; for boarding and washing Reynolds’s horses and those of his servant; and for every newspaper advertisement announcing the sale of Chickasaw lands.19

But that was not all. The federal government billed them for quills, stationery, twelve thousand slips of parchment for the General Land Office, a bookcase, the printing of regulations and blank forms, the construction of a pigeonhole case for the second auditor’s office, and the building of a mahogany bookcase for the office of the secretary of the Treasury. Since someone had to meticulously record and sum up all of these expenses, clerks from the treasurer’s office, first comptroller’s office, second comptroller’s office, General Land Office, Indian Office, register’s office, and second auditor’s office also billed the Chickasaws for their “services” and “extra services.”20

In addition, bookkeepers added itemized surveying costs to the ledger of expenses. The General Land Office billed Chickasaws right down to the chain and link (66 feet and 66 hundredths of a foot, respectively), with the price ranging from $3.50 to $5.00 per mile walked. Three examples of the more than one hundred surveying invoices will suffice to illustrate the government’s commitment to passing on the expenses of deportation to the victims:

| SURVEYOR | MILES | CHAINS | LINKS | COST |

| Abraham F. Rees | 318 | 78 | 16 | $1,275.91 |

| Olsimus Kindrick | 326 | 71 | 35 | $1,307.56 |

| Volney Peel | 240 | 66 | 22 | $842.89 |

Between 1833 and 1841, the General Land Office charged the Chickasaw Nation a total of $114,324.21

For all of the scrupulous attention to accounting, the Chickasaw Nation later identified over $600,000 of suspicious or fraudulent charges—a massive sum that in today’s dollars would employ an army of nearly 8,000 laborers for a full year. The charges ranged from the negligible, an unwarranted $2.75 for stationery, to the indefensible. John Bell, the president of the Agricultural Bank of Mississippi, for example, received $20,000 of Chickasaw funds for reasons unknown. Simeon Buckner, a steamboat owner, received $77,401 for transporting 5,338 people, when in fact no more than 1,500 traveled by water. Perhaps most egregious was the expense to feed 2,464 more people than were deported. The Chickasaws suspected that the federal government had continued billing them for rations even after the supposed recipients had died, including the 800 individuals carried off by smallpox soon after arriving in the West.22

The Chickasaw funds that were not embezzled or drained away by armies of clerks were subjected to a separate assault. Soon after Chickasaw leaders had signed the Treaty of Pontotoc of 1832, they objected vociferously to the article that placed national funds in trust with the United States. “We wanted this money in our own power,” they insisted. “The investment of any part of the proceeds of the reserved lands,” they declared, “was and now is object to.” Levi Colbert condemned the U.S. agent’s paternalism: “he says my nation got no sense, I tell him, if my people make a bad bargan it will be our loss, not the government, he says he knows best for us.”23 Colbert was right to be wary. For the federal government, what was best for deported families turned out to be secondary to what was best for bankers.

Using the trust fund that accumulated from land sales, the secretary of the Treasury purchased over $2.5 million in state bonds, including $1.3 million in Alabama bonds alone. In another era, the investments would have been conservative and unobjectionable, but in the late 1830s, the market was flooded with state bonds that were rapidly depreciating. The purchases seem to have been timed to prop up ailing financiers and ill-conceived state-sponsored projects. Alabama bank president B.M. Lowe wrote to the secretary of the Treasury, “I beg to add that you would greatly oblige the Institution I represent, as well as the community where it is located by taking the $250,000 now.” The secretary obliged by purchasing the bank’s bonds. In similar straits, J.D. Beers expressed his desire to the commissioner of Indian Affairs that the Treasury immediately purchase the Alabama bonds he had underwritten. “Under the circumstances I should esteem it a favor.” A few weeks later, he described “this pressing time for cash” and outlined for the secretary of the Treasury a plan to infuse New York (and his own bank) with “a large sum” of specie, if Wall Street financiers “should get a share of government business.” The Treasury obliged by purchasing $65,000 in bonds from him at a 4.5 percent premium, though they were selling at a 5 percent discount in London. Likewise, Robert J. Ward, director of the Bank of Kentucky, used his personal connections to Andrew Jackson’s advisor Francis Preston Blair to secure funding for his struggling financial institution. He was “anxious” to sell $350,000 in municipal bonds “for the benefit of the Chickasaw Indians,” he explained to his fellow Kentuckian. “You will confer a great favor on your native state by making the arrangement,” he appealed.24 The Treasury Department purchased $150,000 in Kentucky bonds.

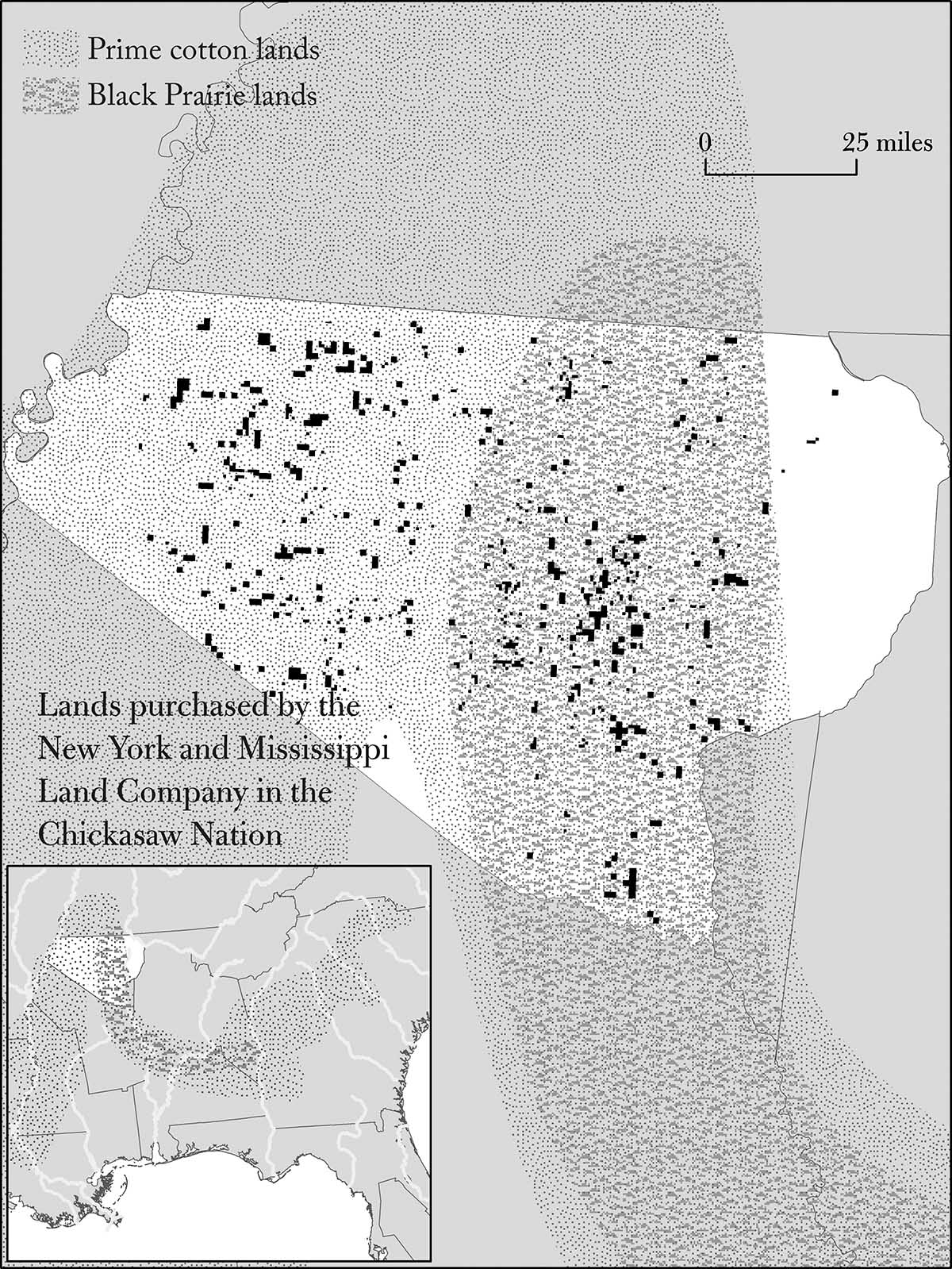

A copy of an Alabama bond sold to the Chickasaw Nation. Holders detached and returned the coupons on the lower half of the sheet to collect the interest. The penciled note states, “105 per 100,” or 5% above par.

Other politically connected favorites benefited through a special arrangement between the Alabama state bank in Decatur and the Treasury Department. Hard money was scarce in the South, especially after Andrew Jackson’s specie circular of July 1836 required that all public lands (including native lands) be purchased with gold or silver. The Decatur branch saw an opportunity when the Treasury Department bought $500,000 of Alabama state bonds using the Chickasaw national fund and deposited the specie in Decatur. At the request of the bank president, the secretary of the Treasury permitted speculators to borrow specie certificates representing the Chickasaw gold and use the paper to purchase Chickasaw land at the public auctions in Pontotoc, about 140 miles to the west. The General Land Office then redeposited the certificates in the Decatur bank, where speculators borrowed again from the replenished pot to purchase still more land. In theory, the scheme might have benefited deportees—more buyers meant more bidding and higher prices for their land—but in practice, it served mostly to give a “decided advantage” to a subset of speculators, as one rival complained. The major investors colluded with each other and by “force of capital” eliminated stray competition, permitting the purchase of the best lands, worth $10 or $20 per acre, for close to the minimum price of $1.25 per acre. “There has never been a sale in the United States perhaps,” one speculator celebrated, “when those who had money, have done better with it.”25

The details of this fleecing, complicated as they are, ought not to distract from the bitter irony that lay behind the Treasury secretary’s mahogany desk, the second auditor’s pigeonhole case, and the Chickasaw specie in the vaults of the Decatur bank. The United States made Chickasaws finance their own dispossession and pay for their own deportation.

~~~

NOWHERE DID the speculators destroy as many families as in the Creek Nation. “On one side,” observed a federal officer, there was “wealth” and “active capital”; on the other, he continued, there was “squalid poverty and deep distress.” The first wave of invaders staked claims, even if illegal for the moment, to valuable cotton land in eastern Alabama. They built houses, constructed mills, cut down timber, and plowed fields. Nathaniel Greyer seized twenty-four acres from “an old helpless Indian woman.” A Mr. Logan avoided the hard work of farming, even on someone else’s already-cleared land, and instead dedicated himself to stealing Creek horses and cattle. Ignoring the native residents, occupiers trespassed on long-established farms, plowing fields and raising fences. “In many instances,” reported Neha Micco and Tuskeneahhaw, “we are entirely fenced up.”26

The second wave of invaders consisted of speculators, eager to purchase Creek reserves for a fraction of the market value. Sometimes they enlisted the help of local sheriffs, who seized Creeks and imprisoned and tortured them, until they surrendered their land for a pittance. On other occasions, they torched Creek houses, driving off the residents with firebrands. A federal marshal who tried to intervene was nearly blown up in a booby-trapped house. Speculators especially were drawn to dying or dead individuals, since it was relatively easy to seize control of their reserves, sometimes by coaxing young orphans to sign an “indenture,” written in legalese, that conveyed their rights to the land. The indenture was accompanied by an oath, in which subscribing witnesses—“highly respectable citizens”—swore that the orphaned children, “by making their marks,” were acting voluntarily. This bit of theater left the survivors to starve. Creeks, Opothle Yoholo complained, were “helpless sheep among devouring wolves.”27

As for the living, speculators devised one particularly effective ploy. It hinged on the fact that many certifying agents were corrupt and had a direct interest in the transactions that they were charged with validating. At little cost, a shrewd speculator could hire a dishonest and desperate Creek to impersonate a neighbor before the certifying agent. “In this way,” explained Opothle Yoholo, “a few hundred dollars and four or five Indians could sell all the land in the Creek purchase.” Eli Shorter, accused of running such a scheme, claimed that it was difficult to differentiate Creek names. Even the most honest of men, he insisted, “can scarcely avoid, in some instances, getting hold of the wrong Indians,” though elsewhere he reportedly admitted that “it made no difference with him whether he had the right Indian or not.” When Creek farmers protested that their land had been sold by imposters, judges told them to bring “white proof,” since courts did not permit “colored persons” to testify against whites.28

Sometimes speculators did not bother to employ impersonators and instead hunted down the legitimate Creek landowners as if they were “malefactors or wild beasts,” harassing them until they signed away their homes. One speculator pursued Irfulgar all the way to the Cherokee Nation, where he finally coerced the tired and despairing refugee to sell his property for a quarter of the value. Takhigehielo lost her land closer to home, after a seemingly friendly neighbor invited her to share his fresh peaches. Then, in exchange for three handkerchiefs and some flour, he made her mark a piece of paper. It was of course a deed, though she “knew nothing of the object of it.” Another woman was cheated of her land with the assistance of her nephew, who received five “little pieces” of “the meanest kind of calico” for his efforts. A third woman, named Suhly, sold her land only after speculators threatened to kill her. She signed a deed and walked away in tears.29

As the “harvest” came to an end, wrote one speculator, they “rogued it and whored it among the Indians” in a final frenzy to consume the remains of the nation. The federal government, concerned that fraudulent contracts would lead to lengthy legal battles and delay the deportation of Creek families, threatened to halt the certification process. Facing the termination of sales, Shorter urged his partners onward. “Give up the beautiful Miss Jenny for the present” and “lay aside” poetry, he chided one associate. “Swear off from the society of ladies for one month,” he scolded another. The “great struggle,” he declared, “should be for the most valuable lands.” “Every man,” he exhorted, “should now be at his post.” Shorter and his partners gathered the desperate Creeks in camps on the side of the road, drilled them in the procedure of deceiving the certifying agent, and promised to pay them $10 for every contract. No matter if these sellers were not the true holders of the land: “Stealing is the order of the day.” “Hurrah boys!” Shorter’s partner exclaimed. “Let’s steal all we can.”30

In April 1835, Andrew Jackson suspended the certification of sales, and the speculators turned their attention from Creek lands to the Creek people themselves. Devising yet another scheme to take advantage of the dispossession of the South’s indigenous residents, they lobbied the federal government to privatize deportation. They relished the idea of profiting from both Creek lands and the deportation itself, and the ever-parsimonious commissary general George Gibson desired to save money. In September 1835, the federal government awarded a no-bid contract to John W.A. Sanford and Company to feed, transport, and provide medical care to the deportees. “We can make a hansame amount to compensate us for our time” and “trouble,” John Sanford, a Georgia businessman and politician, explained to Gibson. The contract, he assured, “is much less than the government has ever be able to emigrate these people for.” Promising to square the circle by making deportation both cheap and trouble-free, Sanford insisted that he could complete the operation “with full justice to both the Government, and the Indians.”31

Creeks were furious. The company’s partners were the very people who had stolen their lands. They “would die,” they said, before agreeing to place themselves under the control of men who “would abuse them.” In a letter to President Jackson, Opothle Yoholo denounced the “company of speculating contractors.” But both George Gibson and Lewis Cass defended the privatization. “The more capital and force,” Gibson ventured, “the greater will be the efficiency of the company in the removal of the Creek Indians.” Cass lectured Creeks that outsourcing would be “more economical” for the United States. With dubious logic, he insisted that it “is therefore better for the government and cannot be worse for you.”32

Between December 1835 and February 1836, John W.A. Sanford and Company transported approximately five hundred Creeks west. With the future of the contract resting on this trial run, the outfit made every effort to ensure a smooth operation. As luck would have it, decent weather and good health ensured that only two people died during the journey. But because other Creeks were unwilling to place themselves under the control of speculators, the company’s ambitious plans remained unrealized.33

In Alabama, Creeks survived by eating bark off trees and consuming rotten animal carcasses. “There was no garbage that they would not greedily devour,” wrote one witness. He commented that starving families, so desperate as to consider eating their own dead, felt forced to take “from those who have to spare,” the well-fed residents of surrounding U.S. settlements. The most wretched of the dispossessed—hungry, homeless, and drunk—could be seen staggering about, with bloodshot eyes and “clotted and bloody garments.” “I talk to them but they have nothing to Eat,” said Opothle Yoholo. “What can I do,” he protested; “they must Eat, they cannot live on air.”34

Armed white men patrolled the area surrounding Columbus, allegedly to defend the town from bands of starving Creeks, who were, in Eli Shorter’s words, “insolent, arbitrary, and warlike.” But more than one person believed that the patrols were a “contemptible” farce, as one federal official charged, designed by speculators to drive off the desperate families living across the Chattahoochee River.35 The conflict between starving refugees and avaricious colonizers would soon come to a head.

~~~

THE FANTASY of an expulsion that was both a blessing to the victims and a source of profit to U.S. citizens, that was at once altruistic and self-serving, did not die easily. Despite four years of disappointment, Commissary General George Gibson could still dream in 1835 of creating a system of transportation that extended to the western margins of the United States and that made every detail of the operation “perfectly intelligible” to his subordinates working at 17th and G streets. Gibson’s dogged optimism, shared with many of his clerks, reflected an unquestioned confidence in the superiority of the United States over the uncivilized and inferior peoples within its borders. If Native Americans often seemed “uncertain in their movements, slow & vacillating,” then his hardworking office staff simply needed to redouble its efforts. Given their upbringing, training, and general loyalty to President Jackson, few were ready to concede as yet that Native Americans had their own desires and goals.36

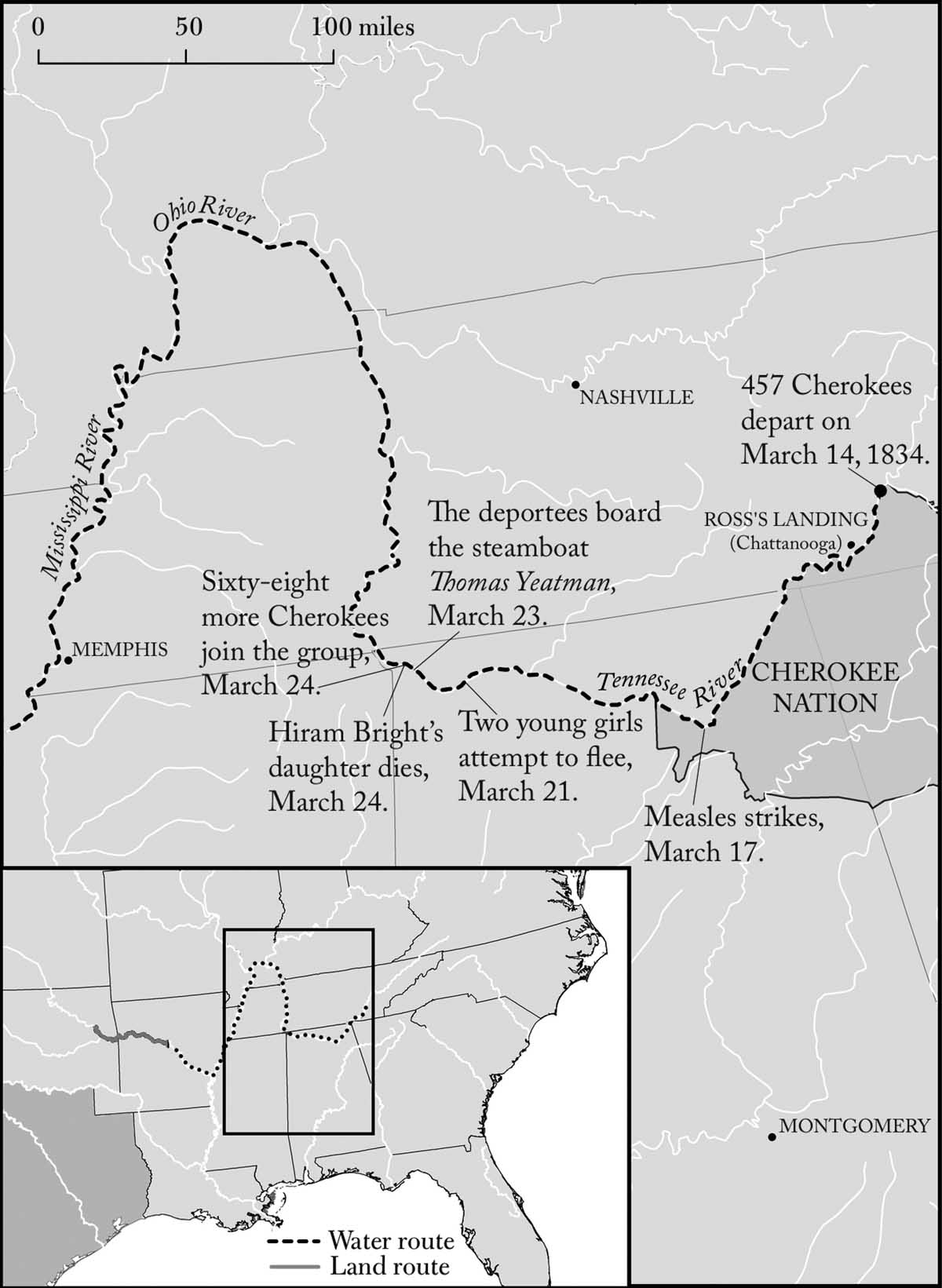

Joseph W. Harris remained among George Gibson’s most dedicated and tireless of field officers, even after presiding over a calamitous deportation that would have demoralized most sensible people. In March 1834, the young West Point graduate had set out down the Tennessee River, escorting 457 Cherokee women, men, and children who had decided to escape the increasingly dangerous conditions in their homeland. They floated down the river on flatboats for nine days. At Waterloo, Alabama, in the northeastern corner of the state, they boarded the steamboat Thomas Yeatman, joining sixty-eight other deportees who had been stranded at the river port. Since the Yeatman could accommodate only 180 people in comfort, the captain lashed two of the flatboats to the steamer. This unwieldy vessel, akin to a floating refugee camp, transported its passengers to the Ohio River, where it added a keelboat. It then proceeded down the Mississippi to the mouth of the White River in southeast Arkansas. There, on March 31, the detachment encountered two hundred Cherokees who were transporting themselves west at their own expense. The refugees in this second group were ailing, and Harris agreed to take twelve or thirteen of the sickest aboard the Yeatman. They were perhaps the source of the contagion that soon began to destroy the officer’s charges.37

March 14 to March 31, 1834. The first two weeks of the journey west for Joseph Harris’s detachment of Cherokee refugees.

At first, the deaths mounted gradually from a variety of causes, as Harris reported in his journal:

APRIL 5: “buried here the girl child of Oasconish a Cherokee”

APRIL 6: “Stephen Spaniard’s girl child died this morning of measles”

APRIL 7: “Bear Paw’s boy child died this morning of dysentery”

APRIL 9: “Henson’s child died today of the worms”

APRIL 10: “Richardson’s child died this morning.”38

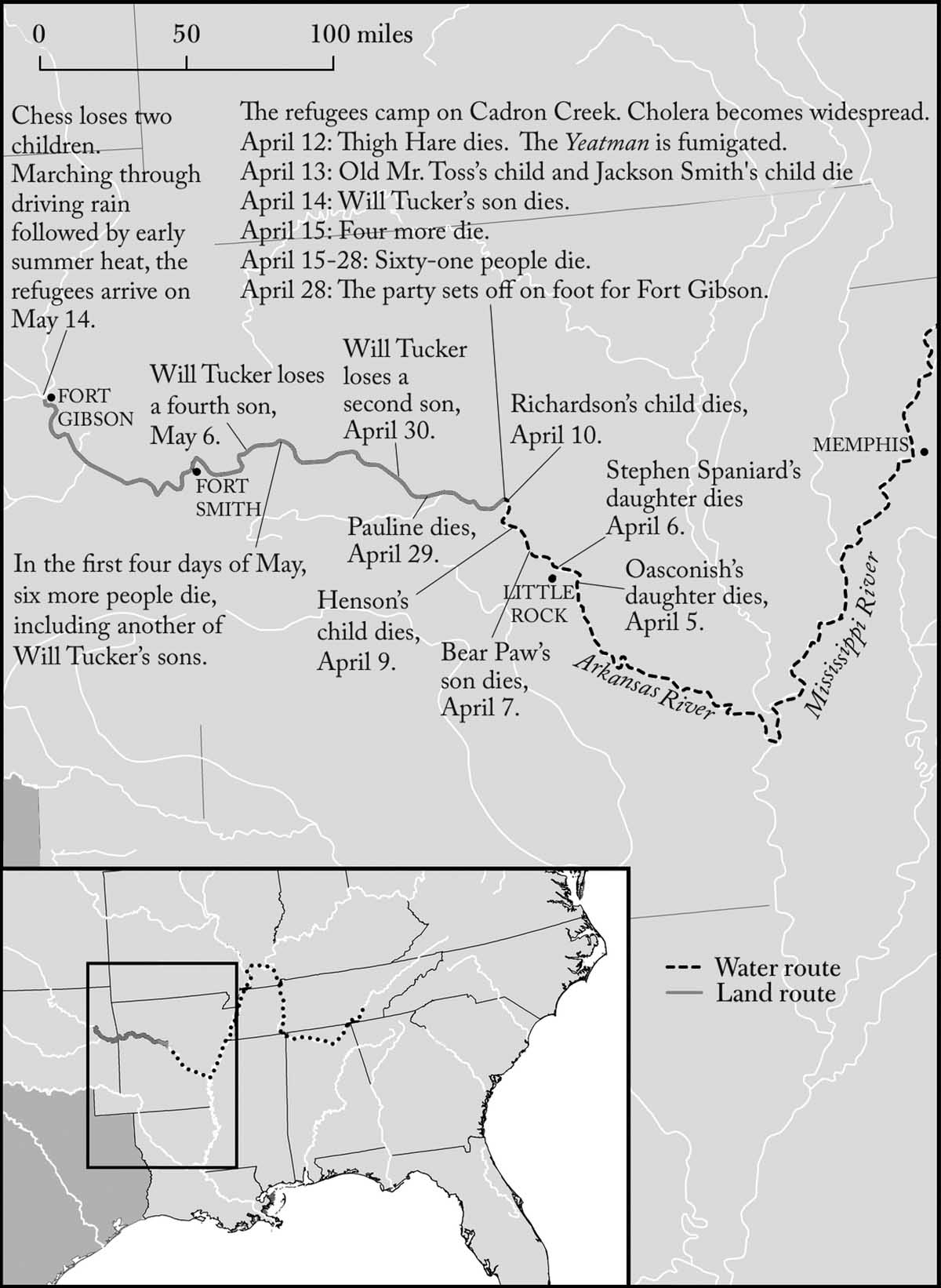

It was impossible to preserve “a proper police amongst these people,” Harris complained, and the Yeatman had therefore “become impregnated with a foul atmosphere.” On April 11, the detachment reached Cadron Creek, about fifty-five miles above Little Rock, and began setting up camp in preparation for the two-hundred-mile march west to Fort Gibson, in what is now eastern Oklahoma. The next day, Thigh Hare was seized with “violent spasms of cramps & watery discharges,” obvious symptoms of cholera. He died that night.39

The makeshift camp quickly became contaminated with V. cholerae. Five or six people died almost without warning, and children began to succumb daily. The microbe wiped out entire families. In the space of two days, Black Fox lost his wife and three children. Will Tucker lost four sons. Over one three-day period that began on April 17, twenty-three people died. Harris desperately sent for medicine and tried to hire wagons, but his efforts failed since no teamsters dared to approach the diseased camp. A local doctor who risked tending to the sick caught the microbe himself and died after a brief but agonizing sickness. “His was one of the most painful deaths I have witnessed,” wrote Harris.40

April 1 to May 14, 1834. The final six weeks of the journey west for Joseph Harris’s detachment of Cherokee refugees.

On April 28, Harris ordered the refugees to break camp and set off on foot on the seventeen-day journey to Fort Gibson. By the time they reached their destination, two full months after departing their eastern homeland, eighty-one of Harris’s charges, or about one out of every six people, had died, including at least forty-five children who were under ten years old. At Fort Gibson, Harris filled out paperwork for the War Department and then returned east “by easy journeys.” “From my Experience,” the officer wrote with characteristic reserve, “I would say that humanity forbade the further transportation of the Cherokees by water.”41

Somehow Harris was not discouraged, and he turned his attention to the expulsion of the Seminoles from Florida. This next deportation, if modeled after the “plan of operations” that he drafted in 1835, would be more efficient. “These papers have been drawn up by me in consequence of my belief in the necessity of a speedy adoption of some systematic plan,” he explained. He excused the length of the thirty-one-page document, declaring that he wished to describe “the very minutiae” of the operation.42 Like so much of the paperwork that had preceded it, Harris’s plan had the virtue of being precise and methodical, with the single defect that it was divorced from reality.

Harris’s “plan of operations” to force several thousand Seminole people from their homes and ship them to the farthest reaches of the United States envisioned a system that ran like clockwork. On a fixed day, the refugees, directed to be “prompt and punctual,” were to collect themselves in camps at Tampa Bay, where they would be divided into companies of five hundred and carefully enumerated, recording the age, color, and sex of each person. “Too much accuracy cannot be observed with regard to the Muster Rolls,” Harris instructed. From Tampa Bay, the first division of refugees would be placed on transports and ferried west along the Gulf Coast to Balize, a port at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Once there, they would not set foot on land. Instead, steamboats would pull alongside to collect each company, allowing six square feet of deck space per person. Heading up the Mississippi and then ascending the White River, the steamboats would “travel industriously & without stoppage.” As a measure of protection against the spread of cholera and other deadly diseases, the vessels would be “thoroughly policed” and fumigated daily with chloride and lime. After this orderly trip upriver, the refugees would debark in central Arkansas to begin a 250-mile march overland to their final destination on the western border of the United States. Sentinels would rigorously patrol each camp, especially monitoring use of the pit latrine. “The Indians,” wrote Harris, “should be required to use it, and it only.” In the morning, the refugees were expected to break camp punctually. With such exacting precision, it was a “mere matter of calculation” that the first division of Seminoles would arrive at its destination the night of March 4—assuming, of course, that the weather did not interfere, the refugees cooperated, the companies remained in perfect health, food supplies arrived as scheduled, steamboats were supplied with adequate water and wood and had no mechanical problems, and rivers remained high and clear of snags. Meanwhile, the transports would return to Tampa Bay to receive the second division, exactly on February 3, and the model operation would repeat itself.43

Harris especially recommended constant and forceful supervision of the deportees. “The observance of an uniform system of police is all important,” the former West Point cadet wrote in a section dedicated to the subject. The police were to exhibit “a general good will and a manly regard for the welfare of their charge,” without “descending to vulgar familiarity.” The “laws” necessary to maintain sanitation, keep the peace, and issue rations were to be clearly explained to the dispossessed, who were to be made to understand the “propriety & certainty of their execution.”44

Well-meaning and thoughtful within its narrow limitations, Harris’s plan was among the last of the zealous and unworkable schemes to deport people devised by the commissary general’s office. In November 1835, a few months after Harris laid out his finely wrought proposal, George Gibson admitted that “active operations of the year have not been productive of such results as might have been anticipated.” A party of Odawas from Maumee, Ohio, at the west end of Lake Erie, had positively refused to relocate, after learning that the lands west of the Mississippi were “hard and flinty” and the region “sickly.” The Seminoles still would not agree to move, despite a large and intimidating military presence in their homelands, and the Creeks had departed in “a very insignificant body.” As for the Cherokees, only a few families had journeyed west as yet. No matter how “strenuous” Gibson’s efforts, native peoples were not cooperating.45

Six years had passed since the “Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians.” Over sixty thousand people remained to be deported from the East. Speculators, planters, and politicians were increasingly impatient. Lobbyists stalked the halls of Congress, offering a share of the profits if their speculations in indigenous lands remained secure.46 And planter-politicians eagerly anticipated the slave empire they would build after expelling native residents. Altruism would have to yield place to swiftness and self-interest. The act of expulsion would soon devolve into a war of extermination.