“It has nothing to do with thinking, it has to do with knowing. You should know.”

They were lunching at the Barney Greengrass aerie, on the terrace that overlooked the windswept postcard of Beverly Hills—one of those crisp, automatic days that trigger nostalgic dominoes of déjà vu.

“He’s happily married,” Rachel replied.

The agent threw back a creamy neck and snorted. A Jewish star lay on her olive skin like a delicate inlay. “They’re all happily married, that’s part of it. They love going back to Mommy.”

Rachel liked staring at her face; it was out of kilter, like a Modigliani. “He’s not that way, Tovah. They just bought a big house.”

“There’s no way he’s going to go from where he was to where he is now with the kind of money he has made in the time he has made it without some instant gratification, Rachel. Of the genital variety.”

The women laughed. The subject was Perry Needham Howe, a television producer and UTA client who’d recently hit it “large.” Rachel had worked as his assistant almost three years, not once catching the scent of adultery—not even a whiff.

“Are you PMS?”

“Because you always end up grilling me about Perry’s sex life when you’re PMS.”

She was a funny, contradictory girl who’d become Rachel’s best friend on the planet. Her father, Dee Bruchner, was a senior agent at William Morris; ever the rebel, Tovah defected to UTA, where she quickly corraled a group of young writers who cut their teeth on shows like Larry Sanders and were now creating hip, middle-of-the-road TV of their own—the Gary David Goldbergs of tomorrow. But Tovah was shrewd: she wanted a finger in all the pies, including a slice of Perry Needham Howe. She was “attracted to him physically,” but that didn’t explain her ambitions—most men were attractive that way. Her interest could be chalked up to good old-fashioned agenting, pure and simple. Tovah knew that pushing him toward the unexpected, seemingly oddball target—say, sitcoms or one-hours—was the long-haul thing that would keep him at the agency. Smart thing, too. Perry was cautious at first but already loosening up, flattered by her spirited attentions. Tovah told him she was going to push him straight through syndication, into Bochco country.

Rachel was forty-four and Tovah barely twenty-six—worlds apart, with worlds in common. The agent’s family went to Beth-El, the temple where Rachel’s father had been cantor. Tovah was still fairly observant. The mother, long divorced from Dee, became a Chabadist and met an engineer through a shiddach. Rachel, the prodigal Jew, loved hearing the details of an arranged marriage: how they weren’t allowed to touch until they wed and how during courtship the front door was always left ajar, for modesty. “Orthodox Judaism is wonderful,” the mother told her when Rachel went to Tovah’s for Shabbat, “because there are so many rules and you just have to follow them. The rules do not bend.”

“I visited the set of this miniseries,” said Tovah, tucking into a sturgeon omelette. “A writer I represent. They were using black leopards—big, beautiful cats. Oh, Rachel, you would love them. There was this woman trainer there, gorgeous, with a leopard-skin belt! Like out of Cat People. There were all these warnings on the call-sheets: ‘No children or menstruating women allowed on set.’”

“Then I’m safe.” Rachel hadn’t had a period in two years, not a real one, anyway. She was a runner and had always been irregular.

“I told you, just go see an acupuncturist.”

“Maybe it’s menopause.”

“You are not menopausal, Rachel, I’m sorry. I told you who you should see. Watanabe, he’s the best, Crescent Heights and Sunset. And stop jogging. No one even does it anymore.”

“Tell me about the cats.”

“These cats…once they’re out of the cages, the trainers don’t allow any movement, especially in the distance—their eyes go to the horizon, right away. It’s veldt instinct.”

“Oy guh-veldt.”

“And little kids—the woman said the cats see kids as, like, a meal. So, she lets them out of the cages. I’m hiding behind the camera…she takes the leashes off and everyone gets quiet, I mean dead, a very weird moment. This giant gaffer looked like he was going to shit in his pants! Did you hear about that woman who was killed up north, by the cougar?”

“God, Tovah, you’ve really got the bloodlust.”

“Someone at the agency actually knew her. In Cuyamaca—it was in the paper. It’s a recreation area, a park where people camp. There’s been lots of people killed by lions this year. Very Joan Didion.”

“What happened?”

“She was jogging.”

“Without a Tampax, no doubt.”

Tovah shot her a “you’re next” look. “It said in the article that the mistake she made was to flee. Well, excuse me! Evidently, they like to take their prey from behind—that part doesn’t sound so bad. This ranger they interviewed said anyone confronted by a mountain lion should maintain eye contact, make noise and wait for it to leave. Right! I mean, that’s what I do with my lawyer! But a mountain lion?”

They were supposed to meet at the track, but Calliope never showed. When Rachel got home, a message on the machine apologized for standing her up. “I hate it,” said Calliope, “that you don’t have a phone in your car.”

When she was twelve, her father was murdered in a New York subway. The cantor’s killer was never found. Calliope renounced Judaism and moved the family—Rachel and her brother, Simon—to Menlo Park. It was at Stanford that she began the metamorphosis into Calliope Krohn-Markowitz, renowned Hollywood shrink.

The children didn’t fare as well. Rachel lived in colorless communes and volunteer clinics. In Berkeley, she ran day-cares, shelters and co-ops, life an unsweetened wafer, sober and unsalted. Forty and unaffianced, she moved back to the Southland to study law for a time before dropping the thread. Calliope enlisted her in showbiz battalions, where Rachel won the Purple Heart for neurotic conscientiousness, lack of ambition and over-qualification. She felt close to superstar Mom but didn’t see her much; admiring from a distance, like one of her magazine profiles. As for brother Simon, he was a lost soul, a burnt-out tummler—sometimes she wondered what there’d ever been to burn. He was kind of an exterminator and called his business the Dead Pet Society.

Soaking in a tub, candles burning, washcloth over eyes, she jogged along Angeles Crest Highway—a lion suddenly across her path. What would she do? Rachel shivered, imagining the last moments of a deadly attack. A long time ago, there was a story on the news about a woman who’d been killed while tracking Kodiaks in Alaska. Her final radio transmission was “Help! I am being killed by a bear.” The horrific refrain stayed in her head for months.

Oddly, Rachel had forgotten all about a clipping she’d attached to the fridge some months back. She reread it before bed, with her muesli.

A woman on a camping trip in Mendocino stabbed a rabid cougar to death with a kitchen knife; her husband lost a thumb wrestling it off. “None of us panicked, to tell you the truth,” the woman told a reporter. “But we moved swiftly.” People were capable of stupendous things—that meant Rachel, too. It would have to mean her. And why not? She clung to the image of the woman, suburban, untried, hand on hilt of serrated blade plunged deep into the small heart of a dank hard-breathing thing trying to extinguish her life.

Perhaps Rachel would move swiftly when her time came—because something was stalking her, that much she knew. As a girl, running home from the playground at dusk, she pretended something was after her. There was something, her own soft shadow catching up with itself, frozen a moment, then melding, overtaking: no one ever told her shadows had shadows. It was upon her again after all these years, crazy Casper energy, flapping like the sail of a toy boat in a squall—shadow of her father’s shadow—and the cantor’s voice chased alongside, like a bogeyman.

The bogeyman of psalms.

Perry Needham Howe

Seven years ago his son died of a rare cancer and now Perry had something in his lungs exerting its mordant claims. The dead boy’s sister, Rosetta, was flaxen-haired, pink-skinned and almost thirteen; had he lived, Montgomery (they never used the diminutive) would have been a dedicated brother of around sixteen, come June. Graduation days.

The doctors said in the first year of an illness like Perry’s—“stage-four adenocarcinoma”—there was ninety percent mortality; after twelve months, a hundred percent. Chemotherapy might add six or eight weeks. When Perry asked how long the treatment lasted, they said, “You’ll never get off it.” You did the chemo until you died, what candid caretakers described as more a “leeching” than anything else.

Curiously, he didn’t have much fight in him. The professionals translated that as depression, but Perry didn’t feel depressed. He felt like one of those existentialist anti-heroes in the novels he’d read back in college—dreamily disburdened. Maybe all that would change, he thought, and in a few months he’d wake up screaming for Mommy the way pilots sometimes lose it when they go down. That Perry was asymptomatic didn’t help him feel less surreal about his predicament; blood-stool or a little double vision would have gone a long way. At least then, he could become a proper fatal invalid. As it was, the producer was living an ironic “television” reality. He even made a halfhearted stab at getting hold of kinescopes from Run for Your Life, the Ben Gazzara series where the smirking actor learns he’s terminal. It was The Fugitive, with a Camus makeover—the one-armed man was Death.

A routine X ray showed nodules on the lungs. There was the usual hopeful speculation the little balls might indicate an infectious process such as TB or histoplasmosis, transmitted by an airborne fungus kicked up by the quake. Far-fetched but within the realm of possibility. When the cancer was confirmed, his wife became obsessed with the idea the family had been exposed to something environmental. What else would explain two cancers hitting like that? The doctors said there was no connection, but they always said that—there was never a connection between anything. That they hadn’t found Perry’s “primary organ”—the point of origin—made it all the more heinously suspicious. Jersey raked over the past, when her baby was alive, searching for clues, tearing open old wounds with a monstrous fine-tooth comb.

After a decade in the Palisades they relocated to North Alpine, in Beverly Hills. Jersey had mixed emotions about giving up the house where Montgomery lived—and died—but it was time. For Rosetta, it was easy. She was getting hormones and any kind of break with the familiar foretold great adventure (you would have thought they were moving to Paris or England). The Antoine Predock trophy home—walls covered with Bleckners and Clementes—cost around four million. Across the way was Jeffrey Katzenberg’s pied-à-terre; it was that kind of neighborhood. Lately, Perry had been looking to buy a “weekender” in Malibu, and the one Jersey liked best was a few doors down from the Katzenberg beach house. You couldn’t get away from the guy.

A syndicated show about real cops made Perry Needham Howe very rich. He knew he’d gotten right place—right time lucky: in a nation of voyeurs, Streets was a front-row seat to the cartoonish orgy of crime that was the American nightmare. Imitators were legion, but Perry’s half-hour was the mother of them all. Its simplicity couldn’t be further distilled: cops chasing crooks in real time, the jiggling camera and panting, out-of-shape officers lent proceedings the kinky familiarity of coitus, without the mess—they even threw in the handcuffs. Cigarettes were smoked while spent, exhilarated fuzz offered post-bust blow-by-blows. Once in a while, if everything jibed, episodes had Emmy-worthy story arcs: like the one with the body in Hancock Park. An elderly bachelor had been murdered. His car was missing and a detective said it smelled like “sex gone bad.” (A criminologist’s phrase, currently in vogue. Perry heard a stand-up on one of the cable channels use it to define his marriage.) A local minister reports a call from a teenager in Vegas who confesses to the crime and wants to turn himself in. At the end of the show, the killer tidily appears at midnight in front of the Crystal Cathedral, no less—in the victim’s Porsche. The minister asks the cops if he can say goodbye to the wayward hustler. “Just tell the truth,” says Father Flanagan to the kid, like something out of a thirties meller. Streets could give NYPD Blue a run for its money anytime.

Perry was on his way to Club Bayonet.

He was meeting Stone Witkiss, the man who created Daytona Red, the early hotshot vice-squad hit. Stone and investors had pumped a few million into an old Mexican bar on West Washington, transforming it into a private wood-paneled oasis with a literary theme. Perry knew the preternaturally boyish Witkiss from way back—Bayonne, in fact—and enjoyed his company.

The place was packed. Steve Bochco and a few execs from UPN were at the bar and Perry said hello. Bochco complimented his show and that felt good. Cat Basquiat shared a table with Sandra Bullock, and Perry thought he saw Salman Rushdie in a far booth with Zev Turtletaub and Sherry Lansing. Stone gave him a hug and Perry followed him back. Along the way, he met Sofia Coppola and Spike Jonze, a handsome kid who made videos (Perry laughed at the resonance of the name). They liked Streets too.

The old friends settled into Stone’s corner table.

“You look great. How’s Jersey? Why didn’t she come?”

“Rosetta’s not feeling so well.”

“Jesus, what is she, sixteen now?”

“Thirteen, comin’ up.”

“What does she have, the flu?”

“I don’t know. It’s a stomach thing.”

“What does Jersey do, hold her hand?”

“Don’t bust my balls, Stone, all right? Are you coming to the bat mitzvah?”

“Of course I’m coming to the bat mitzvah. What am I, a skeev?”

They talked like that awhile, back and forth, like old times. Then Stone hunched, discreetly nodding at a slender, well-dressed man in his early fifties.

“Guy’s a total freak. Know who he is? Patented a computer thing—something to do with screens. Worth, like, three billion dollars. Just bought a house in Litchfield, next to George Soros, two hundred and fifty acres. Jesus, did you read about Soros in The New Yorker?” Stone ordered wine and stir-fried lobster, then circled back. “Anyway, guy lives in a thirty-room house in Palos Verdes. Contractor does a lot of work for me. There’s smoke detectors in all the bathrooms—you cannot repeat this—with tiny cameras inside, so he can watch the ladies in the can.”

Lesser lights steadily made their way to the table. The host looked a little twitchy. Wearing the hats of TV mogul/restaurateur was doing a small number on him; he hadn’t yet found the groove. Funny, Perry thought, what linked them—from Daytona Red to Streets was a bit of a stretch, but Perry knew his friend liked to think he’d somehow smoothed the way. He respected Stone because he’d been through all the hype, glamour and insanity without cracking up. Perry wondered if he should fess up about stage-four. The moment passed and the waiter brought the wine. Stone sniffed, nodding his assent.

“I was talking to this forensic pathologist about Ted Bundy,” Stone said, puffing on a cigar after the last visitors departed. “Bundy was confessing to everything in those last days—trying to forestall the execution—really blowing lunch. You know, they always talked about the ‘long hair,’ all the girls Bundy killed had long hair. The shrinks wondered who it was he was killing, over and over. Know what Bundy told this guy?” He hunched again, cocking his head, intime. “They never released this because it was too fucking hideous. You’re gonna love it. There was a simple fucking reason behind the long hair. He liked long hair because—are you ready?—because, he said, it was easier to get their heads out of the refrigerator.”

The billionaire smiled as he edged past the table. Stone leaned over and whispered. “See the watch he’s wearing?” Perry hadn’t. “Il Destriero Scafusia: what they call a ‘grande complication.’ Ask him to show it to you, he’d love it. Swiss—seven hundred and fifty components, sapphire crystal, seventy-six rubies inside. We’re talking mechanical, nothing digital about it. I used to collect, mostly Reversos and Pateks; had a thirties Duoplan, Jaeger-Le Coultre. Le Coultre’s hot this year. Loved the thing to death. But this one,” nodding at the billionaire again, now at Frank Stallone’s table, chatting up a long-legged girl with a huge mouth, “is the fucking grail—they call ’em ‘super complicateds.’ I mean, the fucking thing chimes, Perry! It shows the changing of the century on its face, the fucking century! I got a watch, cost me seventeen grand, a Blancpain quantième perpetual. Has a moon phase I used to adjust about every three years. And that’s pretty good. But this motherfucker”—nodding to the freak again—“has a deviation of about a day every hundred years.”

Just before leaving, he found himself at the urinal next to Il Destriero Scafusia. A watch like that probably wound to the movement of the wrist; Perry shook himself and suppressed a laugh, scanning the ceiling for hidden cameras. The billionaire followed him to the sink. Had he been keener on inquiring after baubles, Perry might have asked for a look. He’d done enough of that over the years—everything had always been out of reach. Now, nothing was. Nothing, that is, but time.

Ursula Sedgwick

Ursula and Tiffany weren’t homeless anymore. They lived in a house on one of the old canals.

Their neighbor, Phylliss Wolfe, was a producer who sold her Cheviot Hills home after having some kind of breakdown. She called it “Down(scaling) Syndrome”—movie projects were on hold so she could finish her book and get pregnant. She wasn’t happy about the local gangs, but it had always been a fantasy of hers to live this way: in a writer’s bungalow on an ellipsoid patch of grass still called United States Island. She christened the avenue Dead Meat Street because so many were dying of AIDS, or gone.

On Sundays, they went strolling on the boardwalk. Phylliss brought Rodney the dachshund, fearless sniffer of pit bulls; while Ursula and Tiffany had their fortunes told, she binged on cheap sunglasses. They shared life stories over time, shocked to have Donny Ribkin in common. Every little detail about the agent came out, including sexual proclivities—which Phylliss expanded to include the affair with Eric, her ex-assistant. Ursula blanched. It stunned her to learn Donny’s father recently drowned in Malibu; that was someone he never talked about. But the worst thing was hearing he’d been hospitalized for a crack-up. “Hollywood rite of passage,” Phylliss joked. “Don’t knock it till you’ve tried it.” Ursula felt sick inside. He was still her man.

She’d never met anyone like Donny—so smart and chivalrous and full of passion. If that’s what Jews were like, you could sign her up for more. He scared her too, but men did, that was par for the course. He was the first lover to lavish any kind of gifts on her. At a time in her life when she really needed it, Donny Ribkin gave her a whole new way of seeing herself. They used to go “power shopping,” buzzed on crystal. He got her an Oscar de la Renta at Saks, a seven-thousand-dollar strapless sequined gown, and there she was that very same night at a charity ball honoring Forrest Gump’s Robert Zemeckis, the greatest night of her life, speed-grinding her teeth as she eavesdropped on Michael J. Fox and Meryl Streep and God knew who else, Donny’s friends, their smiles like razors. Then he would brutalize her in bed, punching and choking her as he came, reviling her idiot faux pas. How could you say what you said to Goldie? Once he made himself vomit on her. But there was the other Donny, her “Sunday morning boy,” who cried inconsolably for hours on end, begging forgiveness, tears from some faraway place like a sad, hip monster from The X-Files—the Donny who paid Tiffany’s schooling and wept for his dead mother.

He could be cruel, but at least he wasn’t one-sided. Ursula knew nothing but violent men, military father and brothers, men with just one side. The day came when she’d had enough, walked from the trailer park bloodied, holding Tiffany’s bitty hand, living shelter to shelter, freeway to freeway, rape to rape, with only The Book of Urantia to grace and solemnize each day—the Book, with its Morontia Companions (trained for service by the Melchizedeks on a special planet near Salvington) and Thought Adjusters (seraphic volunteers from Divinington). She prayed with Tiffany for the Mystery Monitors to come, “who would like to change your feelings of fear to convictions of love and confidence.”

There was The Book of Urantia and there was her daughter and then one day—off-ramp miracle—there was Donny Ribkin. Now, he shunned her. She still worked at Bailey’s Twenty/20 and began each shift hoping the agent would drop in. The men she stripped for had his face; she made it so. One day it would come to pass. Ursula wasn’t sure how she had turned him off like that—was it her homeless helplessness that turned him on? None of it mattered. This alluring, troubled, soulful man had seen her at her worst and not turned away. For that, she would love him forever.

“You need something to fill this black hole,” Phylliss said. “Donny Ribkin is a panacea. If it wasn’t him, it’d be someone else. Something else. Listen, he’s no catch, okay? He’s fucking loonie tunes. Not to mention a probable health risk at this point. So why don’t you deal with your black hole?”

“Then what do I fill it with?”

“A sausage—a fat, hairy sausage with a ‘Donny’ tattoo.”

“You’re terrible,” she said, laughing. She could still laugh.

“Have you ever heard of Eckankar?” Ursula shook her head. “They call it the religion of ‘the Light and Sound of God.’ The name’s from Sanskrit—it means ‘co-worker with God.’ But it isn’t a Christian thing. It isn’t an anything.”

They said the odd word a few times together. Phylliss told Ursula that she turned to the practice out of desperation: her movie had fallen apart, and she’d suffered the death of a fetus and father—how she’d gone to a hospital to heal but emerged more shattered than whole. ECK reached out and stopped her fall. Since then, it was the most important thing in her life, bar none. “I’ve become a ‘spiritual activist,’” she said. “My New York friends are about ready to do an intervention. I just tell ’em I want to have Yanni’s child. Or John Tesh’s, in a pinch.”

From what Ursula understood, Eckankar was less a religion than it was about dreams and soul travel and accepting other planes. That was familiar ground. She was impressed someone as cynical and sophisticated as Phylliss could have allegiance to a thing so radically ethereal; then again, with the terrible abuse Phyll had been through with her dad and all, you would have to let in something new, unless you wanted to go bonkers. When she brought up Urantia, Phylliss yelped “Dueling cultists!” and strummed an imaginary banjo, laughing her coarse cigarette laugh. Ursula said she had considered converting to Judaism as a way of winning Donny back—that sent Phylliss on a coughing jag. “You’re the only person I know,” she said, “who’s more fucked up than I am.” She invited her to Sunday morning worship services at the ECK Center. After a month of wheedling, Ursula gave in.

She wandered the sunny rooms at peace, as if having already dreamed such a place. Phylliss said those kinds of feelings weren’t unusual—it meant the Eckankar Masters had been busy nudging you to the point where you had enough power to seek them out. As more people arrived, Ursula scanned brochures on “the ancient science of soul travel” and the soul’s return to God. God was sometimes called Hu, pronounced hue, or Sugmad. Through a series of exercises that took just twenty to thirty minutes a day, it was possible to reach a supreme state of spiritual being. One was guided in this pursuit by the Living ECK Master, or Mahanta, who was descended from the first Living ECK Master of around six million years ago. (The first was called Gakko.) The current Living ECK Master, also known as the Inner and Outer Master, was a married man from Wisconsin named Sri Harold Klemp. His picture hung in a modest frame on the wall of the meeting room. The Mahanta’s hair was thinning; there was nothing grandiose about him and Ursula liked that.

Around fifteen people gathered in a circle to discuss the morning topic, “The Golden Heart.” Passages were read from a book of the same name, written by Sri Harold. It was a diverse bunch: an impeccably dressed couple, married fifty-two years, ECKists for seventeen; a carefree, homely, shoeless girl with a wide-brimmed straw hat; a heavy-set, dikey-looking nurse; a couple of friendly, formidable-looking black ladies in their sixties; and two or three fresh-faced professional men who might have been marine biologists or aeronautical engineers. One of them looked disarmingly like the Mahanta. They broke into groups of three. Ursula wound up with the old man and one of the churchwomen.

“The Golden Heart,” he stammered. “Well, that’s just another way of saying Conscience, isn’t it?” He sounded just like Jimmy Stewart and it beguiled her.

When the lady’s turn came, she said one day she found herself en route to an ECK convention in Las Vegas to see the Mahanta. “I said to myself, ‘What are you doing?’ Because I’d followed Jesus all my life and now here I was on my way to see Mr. Klemp. When I got to the convention hall, I saw a halo around his head—I knew pretty well then, I was on the right path. For me, that path is the Golden Heart.”

The leader said it was time to chant Hu, and everyone closed their eyes. Ursula blushed as the voices raised around her, blending, fusing, overlapping—a celestial curtain rose behind the lids of her eyes, wafting so tender in the dark, and she knew what was meant by “the religion of Light and Sound.” How could something so beautiful emanate from people so common and undemanding, people just like her? Yet there it was, irrefutable, like the whistle of a thousand trains, heaven-bound.

She cleared her throat and began, her voice a rivulet joining the stream that fed the Golden Heart.

Severin Welch

This man, seventy-six years old, in robust health and reasonable spirits, has not left his home in some fifteen years, initially because he was waiting for Charlie Bluhdorn to return a call.

That was the putative reason, now hidden somewhat by time’s seductive sleight of hand. His name is Severin Welch, a widower who once wrote for Bob Hope; Charlie Bluhdorn, of course, being the legendary founder and ceo of Gulf + Western. Some decades ago, after indentured servitude to set-up and punchline, Severin Welch began a preposterously ambitious big-screen adaptation of the Russian masterpiece Dead Souls, set in the Los Angeles basin. Where else? It took a certain comic gall. Why Dead Souls? He’d read it in school, written papers on it. He once met a fellow at the Hillcrest named Bernie Ribkin. Horror was where the money was—that’s what Ribkin said when Severin took him to Chasen’s for a little interrogation; horror was the future. He told Ribkin about Dead Souls and the producer liked the title. “Just don’t call it Undead Souls,” he smiled, chomping on his cigar, “or I’ll be suing your friggin ass.”

He worked the script ten years, finishing in ‘seventy-five. Over at Morris, his then-agent—the still redoubtable Dee Bruchner—took a month to read, hating it. But Severin wanted Paramount to have first look and (back then) the client was always right. Dee morosely messengered it to a Yablans underling. Over ensuing months, the agent dutifully tracked the hundred-and-ninety-three-page ms. from suite to suite until it was the faintest blip on the radar screen, then no more.

Severin kept his day job, tinkering with Souls on weekends, a hobbyist possessed. Meanwhile, he wrote sketches for Sammy and Company and worked on specials: Mac Davis and Flip Wilson, and Hope’s twenty-fifth anniversary, with a hundred guest stars—Cantinflas, Neil Armstrong, Benny, Crosby, Sinatra, Chevalier—those were the days. Aside from Lavinia’s painful divorce in wake of her husband’s nervous collapse (she somehow blamed her father for The Chet Stoddard Show fiasco), it was a ring-a-ding good time. Severin and the wife had dinner parties twice a week, and bought a place in Palm Springs on a course. He had just one complaint and it lay in wait at the end of each day: the gargantuan discourtesy of Paramount Pictures.

Months passed—why hadn’t someone the decency and professionalism to respond? Because he was a television writer? That seemed bizarre. Chayevsky had been nominated up and down the street for Network. Didn’t that ring anybody’s bells? Didn’t the Morris agency have any clout? Wouldn’t it have been reasonable for Dee to phone someone up at the studio and say: “Listen to me! You have not responded and my client is angry. He is important to this agency and you owe him that courtesy. Call him—now.” If you don’t like something, come out and say it. I want to hear about it, don’t be shy, meet a guy, pull up a chair. Give it to me with both barrels—what doesn’t kill me sure as hell will make my script stronger. That’s the way Severin looked at it. Anything but the silent treatment.

Another year. Severin, with his golf and gags and pool parties under the HOLLYWOOD sign. He’d throw back a few, then go on a Paramount rant: if the script came over the transom, then, he said, then it would be something else. Whole different story. But Dead Souls arrived by the book, so to speak, through a powerful agency—and Severin Welch was an established writer! One of the wiseacres said he should stand in front of the studio gates naked with a sandwich board, and Severin thought that a swell idea, especially when Diantha bridled. It’d probably kill his agent, but hell, Dee was dead already for all the good he did—sitting on El Camino scratching his ass like a dull-wit stonewalling Buddha. The tragedy was, Severin knew it would be a perfect marriage—the studio that so handsomely produced The Godfather would be the ultimate venue for this multi-textured classic. Knew it from day one but was forced to go elsewhere, finally persuading the agency to send the script to other majors. At least they had the courtesy to eventually express their disinterest. Or maybe Dee’s secretary typed the rejection letters to get him off their backs. Maybe the damn script never left the mailroom—Severin didn’t really know anymore. The whole rude, unseemly business had thrown him for a loop.

With dull awareness of his compulsion, he began to place morning calls to his agent, Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, year in and year out, urging him to appraise “the progress at Paramount.” To keep his finger on the pulse. The first few weeks, Dee thought it another gag from the gagman, but as the inquiries persisted, the agent grew irritated, then angry and finally intrigued by the underlying pathology. It became something of a joke among Morris acolytes; when they saw Father Bruchner at the Polo Lounge or Ma Maison, they never failed to ask after “the progress at Paramount.” Severin still made money for the agency, so his eccentricities were grudgingly tolerated.

From atop his hill, the television writer watched the bilious Paramount parade: Orca, the Killer Whale; Bad News Bears Go to Japan; Players; The One and Only; Little Darlings; Going Ape!; Some Kind of Hero. No wonder they’d been too busy to respond! It was like the marathon dance in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?—yet the band played on. He was rankled in some deep, unapproachable place. When his wife delicately suggested he might “talk to someone,” Severin reacted so harshly that Diantha half thought he’d try fingering her as a Paramount spy.

Then one day in nineteen eighty-one, a Morris secretary called to say “there was movement.” In measured tones, cryptic and grave, she told him Charles G. Bluhdorn himself was in possession of Souls. “Mr. Bluhdorn wished to give the script his personal attention,” her words went. A senior agent at Morris who dealt exclusively with the chairman would be calling Severin with a follow-up. In the excitement, he didn’t write down the name. He waited by the phone until six, finally calling Dee’s office. No one was in. After a fitful night, he left messages with the switchboard “regarding Charlie Bluhdorn.” He was on his way down to the agency when Dee Bruchner called back. It had been a few months since they spoke; work had been drying up.

“Severin, what the hell is going on?”

“I want to know what’s happening with Bluhdorn.”

“I don’t have time for this crazy shit!”

“Someone called from the agency—”

“Nothing’s fucking happening with Bluhdorn! Okay? Why don’t you go see a fucking shrink, Severin? All right? How many years have we been doing this?”

“A secretary called, from the agency,” said the client, undeterred. “She said Charlie Bluhdorn was reading my script.”

That night, Dee phoned from La Scala. He sounded drunk and vaguely repentant. The whole thing was a practical joke, he said. When Severin asked what he meant, Dee said, “It must have been a joke.” He reiterated his desire for Severin to seek medical help. “You really should,” he said. “For Diantha. It’s not fair to put her through this. You know, people love you, they really do. They really care.” What the hell was he talking about? In the morning, the disbeliever reached Bluhdorn’s office in New York but was rebuffed. He kept calling, and when Dee found out, he sent a telegram saying the agency no longer represented him and that Severin Welch should “cease and desist” contact or run the risk of becoming a “nuisance.”

Came a gentle temblor in his head, a shifting of plates, and so it was decreed: the matter would be resolved by the definitive telephonic intervention of that high-flying commander, that Mike Todd of ceos, Charles G. Bluhdorn, whose imminent call was not open to conjecture. Severin withheld this magical revelation from world and wife; he wanted to live with it a spell, try it on for size, test its sea-legs. Fear of missing the Call soon tethered him to the house. He might have laughed about such an arrangement—how could he have not, particularly after Bluhdorn’s subsequent death?—but there it was, unreal yet present as the HOLLYWOOD sign. The occasional women’s magazine had been perused, Redbook and Reader’s Digest, but these were the pioneer years of phobic disorder: no clubby Internet or national network of like confederates, mystically moored by zip code demarcation and sundry voodoo Maginot lines. Diantha indulged his epic call-waiting best she could. When she died, swept away by the flash flood of cerebral hemorrhage, Severin could not leave the front yard, so missed the procession. Lavinia poignantly misunderstood, thinking her father unhinged, which he was, though not entirely by grief.

That the Call didn’t come never disheartened, for its presentiment rang in his ears, an astral tintinnabulation like the warm, flirty scent of a holiday roast; Severin, wrapped in a comforter of acoustical yearning. Pink Dot delivered groceries and laundry, and daughter Lavinia picked up the slack—thus ensconced, the old fossil roamed the low-tech shagscape of his Beachwood Canyon home, listening to his precious scanner, reading aloud from Thurber and Wodehouse, Gogol and Graham Greene, anchored by his powerful Uniden cordless and the entropy of the years. Did he really expect a call from a dead man? No: after all, he wasn’t crazy.

There was a piece in the Times about John Calley that he’d read with great interest. The United Artists head had returned to the business after years of lying fallow and was now in the methodical process of sifting through studio archives—the idea being to discover old projects, then revise, update and order to production. They had stuff going all the way back to Faulkner and Fitzgerald.

“It’s very much of an archeological expedition,” says Creative Artists Agency’s Jon Levin, who has researched everything from old production logs to the memoirs of Hollywood legends. “There are only so many movies that were made every year, and a number of more scripts that were developed. So chances are there are good [unproduced] works.”

It went on to say that because of rights issues and liability concerns, boxes of unproduced scripts—some of which had been donated to the AMPAS Margaret Herrick Library—now resided at a remote storage facility for “things that are not supposed to be seen…a no-man’s land.” Severin Welch’s Dead Souls had to be out there somewhere, waiting. If you write it, they will come! And when they did (perhaps Bluhdorn progeny, that would be a nice, a fine irony), Severin would have a surprise: the work of the last five years, gratis. For the busy shut-in had been revising all along, retrofitting for these hard, fast times. The money boys would like that—it would save the expense of hiring a pricey rewrite man. Severin wasn’t too worried about ageism. Charles Bennett (the initials alone were auspicious) had sold a pitch right before he died. Bennett wrote for Hitchcock and had to have been in his nineties. No, the tide was turning. Everything old was new again.

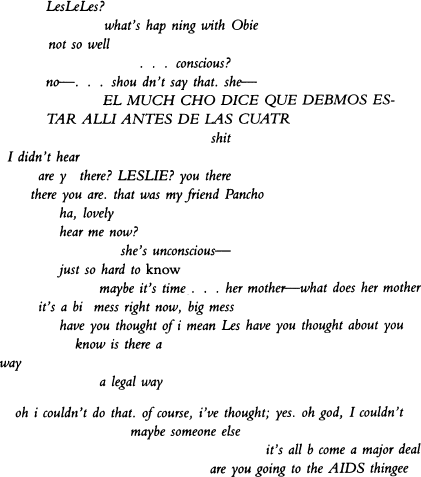

He sat by the pool with the scanner, monitoring car phone transmissions. That was illegal now, but Severin had no fear. He used it as a tool, plucking characters from the vapor, finessing dialogue, shoring up unsafe sections of his work. Writers were mercenary—had to use whatever they could. Originally, the old man’s presciently “virtual” adaptation of the Gogol book submitted Chichikov wandering an antiseptic city buying memories of the dead. Now, as if in sly homage to Mr. Bluhdorn, it would be voices the man coveted instead.

Voices on the phone.

Rachel Krohn

On the first night of Passover, Rachel had a dilemma. She was supposed to go with Tovah to an Orthodox seder but now the agent was in bed with a fever, insisting Rachel go alone.

“But three hundred people!”

“It’ll be easier. Less intimate.”

“Tovah, I won’t know anyone—”

“No one knows anyone, that’s the point. It’s skewed toward singles.”

“I haven’t been to a seder since I was a kid.”

“There’ll be lots of Jews who’ve never been to a seder, that’s what this is, an outreach for singles. You want to meet someone, don’t you? Then just go.”

Rachel was in a cold sweat. For some masochistic reason, she arrived early, and because there weren’t a lot of people yet, it was harder to hide her discomfort. She thought about leaving but remembered her pedigree: her father was a goddam cantor. Rachel Krohn didn’t have to prove a thing to these people.

She mingled awkwardly, admiring the rabbis’ long coats, very Comme des Garçons. A woman asked her to light a candle. Were candles lit each Sabbath night or only on Passover? She was clueless. She only knew you lit candles for the dead, though her mother never did.

Nondescript men in poorly cut suits approached, abashedly letting on how they were Fallen Ones, come back to the fold. There were South Africans and San Diegans, Australians and Czechs, Muscovites and New Yorkers, and a dance troupe from Tel Aviv—the girls were gorgeous. Rachel stared like she used to at counselors during summer camp, envying their tawny bodies and musky élan. Again, she felt like bolting.

She was targeted by a schlemiel. He was about to speak—the mouth opened, showing braces—when a rabbi bounded up and introduced himself as “Schwartzee’s son.” Rachel put a hand out but he demurred.

“I’m a rabbi, I don’t shake hands! I don’t mean to embarrass you. It’s just a choice—the only hand I touch is my wife’s. Let’s just say I don’t like to start what I can’t finish!”

A woman lunged forward. “Then I’ll shake it, I’m his sister!” She pumped Rachel’s hand, exclaiming, “I’m not so choosy!”

Schwartzee himself appeared, holding a clipboard in such a way as to discourage the flesh-pressing impulse. He was coatless and wore Mickey Mouse suspenders. “Moishe Moskowitz,” the rabbi crowed, thumbs tucked in each side, “for the children!” He checked off Rachel’s name and was sorry to hear “my old friend Tovah” was sick. The rabbi’s naked, musty breath evoked a weird mosaic of memory and sensation—of synagogue, family and dread. The doors to the banquet hall swung open and Schwartzee shouted after the guests, “It’s fat-free, so enjoy!”

She entered the cavernous room in haphazard search of a table.

“Rachel!”

She spun around. Standing there was her brother, Simon.

“What are you doing here?” she asked, dismayed.

“I got a call from Schwartzee—there’s something dead in the basement. Could be Lazarus! Or should I say Charlton Heston.”

He wore a dark suit and looked thoroughly in his element—the Dead Pet Detective, born-again. Simon had left a slew of messages that she hadn’t returned.

“You never called me back!” he said, oddly enthusiastic.

“I was going to. I’ve been real busy, Simon.”

“I was just wondering if there was any way I could get with your boss.”

“Simon, I’ve already told you, Perry doesn’t know any of the Blue Matrix people—”

“Oh come on, Rachel! All those people know each other.”

“That’s not necessarily how it works.”

“I have three scripts, okay? Can’t you at least get one to your boss?”

“Simon, let’s not talk about this now.”

“Where are you sitting?”

“Not with you. I’m with about twenty people.”

“Well, excuuuussse meeeeee!” She started to go. “Wait! What does a man with a ten-inch penis have for breakfast?”

Rachel was beyond ill will; she didn’t even feel like leaving anymore. She had accepted her lot as among the condemned.

“Uh, well,” Simon stammered, “let’s see now. Uh, I had two eggs, toast…a glass of o.j.—” He cracked himself up as she moved away.

A blithe, bitchy couple sat across. The woman let everyone know they’d met during one of Schwartzee’s relationship seminars at the Bel Air Radisson. On Rachel’s left was an overweight, attractive Canadian called Alberta. Mordecai, the lovestruck schlemiel with braces, hovered breathlessly, too nervous to sit beside her; he took a chair by the great Province. The place beside Rachel remained empty, a sitting target for the requisite Elijah jokes.

After her father’s death, Rachel’s family joined the landlocked diaspora of the faithless. She had been so far and so long away from the water that the dizzying, chimerical ceremonies at hand made her feel like an ethnographer in the field: symbolic foods on plate, the leaning to the left, naming of plagues—boils, hail, cattle disease, slaying of firstborn…like crashing a meeting of freemasons. Yet when she heard the congregants’ intonations and the indomitable old songs of her father, her otherness burned away. Schwartzee’s six-year-old son (the fertile rabbi’s latest) took to the stage and sang a flitting, singsong prayer. Rachel blotted her tears with the hackneyed inventory of images: Sy at the pulpit, mighty and dour, a gray, businesslike Moses, neck vibrating like a turkey’s when he sang; huge white hands and slicked-back hair; fat gold ring.

Schwartzee asked how many commandments were in the Bible. Someone raised a hand and shouted, “Six hundred and thirteen!” Rachel puzzled over that one during the ritual hand washing. She asked Alberta about it.

“You’re not really supposed to say anything after the washing of the hands,” the big woman said. “Until you eat the matzo.”

“Oh! I’m sorry.”

“Sit in the corner,” said Mordecai, leaning over to be seen. “No matzo for you tonight!”

“It’s tradition,” said Alberta, contritely. “I mean you can, but you’re not supposed to.”

“Then I won’t,” said Rachel, unperturbed.

Mordecai shushed her, holding up an admonitory finger. “Please reply in the universal sign language.”

“It’s all right—really!” said Alberta. “I just wanted to tell you what was traditional.” To her annoyance, Mordecai sang a few bars of “Tradition” from Fiddler on the Roof.

“Schwartzee’s seders tend to go till midnight,” said the woman across, to no one in particular. The boyfriend watched the waiters like a hawk, making sure to get double portions. Timing was everything.

A woman in her sixties was ushered to the vacant seat along with edgy Elijah jokes from the hawk-eyed man, who clearly regarded her arrival as a threat to the food bank. Birdie was from New York and, as it turned out, a cantor’s daughter. She ran a mortuary in the Fairfax district, a chevra kaddisha, or “holy society.” Rachel remarked how difficult it must be to work in such a place, but the woman said it was “her greatest mitzvah.” Birdie was a shomer, a member of a volunteer group that attend the dead before burial. She explained that shomer meant “watcher.” Mordecai made a dumb eavesdroppy joke about “birdie-watching” and the woman tensed her lips in a bloodless smile.

Birdie’s father died just last year, at ninety-five; it surprised her Rachel’s loss had come so long ago. Spontaneously, the younger woman offered that he had been killed.

“What is your last name?” Birdie asked.

“Krohn.”

She stared at her plate, then turned and looked at Rachel with a dead blue eye. “I knew your father,” she said.

“You—knew—”

“Yes. My husband did his taharah.”

“His what?”

“Your father’s taharah. The ritual cleansing—the prayers. He sat with your father before he was buried.”

He took Jersey to all the black-tie benefits and still, hardly anyone knew. That’s how he wanted it. He felt strangely invisible—imperishable, even—a dapper traveler incognito in the land of the living. He hadn’t succumbed to the savage placebos that made one a bald vomit-machine: that would be sheer cowardice. Perry wanted to die on his own terms, not like some whore pretending to be a hero.

They went to the Bistro Gardens for the Hospice of the Canyon, an outpatient program in Calabasas for the terminally ill. Perry liked the irony. He cracked death jokes under his breath, but Jersey wasn’t up to playing Mrs. Muir. A few friends knew, with his permission—like Iris Cantor, their great guide. Iris had networked them through Memorial Sloan-Kettering and was there tonight, along with the usual crowd. There were bevvies of doctors and nurses (Jersey felt like buttonholing Leslie Trott and pouring her heart out) and a monsignor, for show.

On Saturday, it was Suzan Hughes’s birthday at Greyhall mansion. The former Miss Petite USA had married the perennially handsome founder of Herbalife. Jersey was active in the Herbalife Family Foundation for at-risk children, as she was in Haven House, Path, Thalians, Childhelp, D.A.R.E., Share, the Children’s Action Network, the H.E.L.P. Group, the League for Children, Operation Children and the Carousel of Hope. All the “ladies who lunch” loved Jersey Stabile Howe’s energy—and thought Perry was gorgeous, like a young Mike Silverman. Something of the Cary Grant about him. The tragedy of their son’s death was well known and bestowed another, popular facet: they had the dignified weight of a handsome couple who had journeyed to “another country” and come back with slides for future tourists. The ladies spoke of Montgomery as one would an infantine lama, snatched from their midst to fulfill a greater prophecy—cosmic honors to which aggrieved parents must perforce acquiesce.

Jersey wondered what would happen when they found out about Perry; he’d be wasting away by then. The ladies might even revile her misfortune, secretly dubbing it over-kill. (That was a sick thought.) There was nothing to do but master the art of crying in public restrooms. She’d tough it out, had to for Rosetta’s sake, her beautiful little girl. Jersey knew how to cope: she drank Kombucha mushroom tea by the gallon, washing down Zoloft and Ativan. To outlive one’s husband and son! She perversely looked forward to the ladies’ memorial attentions. For now, all she could do was natter about environmental carcinogens—leukemia in the suburbs, toxic seepage, government lies. And across the world, the doomsday cover-up of the corroding containment husk around Chernobyl’s reactor number four.

Stage four…Reactor number—

The Bistro gardenias weren’t completely sold, worried their young friend might be truffle-hunting too far afield. They were more at ease with orphanages and battered women, AIDS and oddball diseases. What chance did plain-wrap adenocarcinoma stand against pediatric exotica? Standing there between Vanna White and a bloated Charlene Tilton, Jersey watched her beautiful blue—blazered husband and blinked back the image of him stone cold dead. Guiltily, she watched the Tadao Ando—designed monolith rise before her: THE PERRY (AND JERSEY?) NEEDHAM HOWE CENTER FOR EARLY DETECTION. The betrayal was more than she could bear—how could she? There was Jay Leno and Steve Allen, LeVar Burton and Charo, Pia Zadora and someone from Laugh-In whose name she couldn’t remember. Perry hooked his arm in hers and charmed the lot of them, all the while turning over the one thing that had possessed him since Club Bayonet: II Destriero Scafusia.

Rachel contacted its makers, and the International Watch Company FedExed a cassette along with a small hardback catalogue. Within the latter was an inventory of prices—a “moon phase skeleton model” pocket watch available in yellow gold, at sixty thousand; a Da Vinci wristwatch, for over a hundred. There were Portofinos, Novecentos and Ingenieurs—and, of course, the rather modest looking eighteen-carat rose-gold Destriero, a grande complication that stood, trěs grande, at a cool quarter of a million.

The watch itself was crafted in the village of Schaffhausen on the banks of the Rhine. Destriero was the name given to a jouster’s steed; one easily imagined such knightly trials unfolding hard by the medieval castle—built from plans designed by Albrecht Dürer—that overlooked the town. Just what was a “super complicated” watch? The voice on the tape explained a mechanism could only be classified as such if three elements came together in its movement: chronograph, perpetual calendar and minute repeater. Among collectors, “minute repeaters” were the most coveted. They were the watches that chimed the hour, quarter-hour and minute, an action originally devised for the blind.

Perry lingered over a bit of text: “Firmly secured inside the movement is a replacement century display slide, which can be installed at the end of the twenty-second century and will continue showing the correct year until the end of twenty-four ninety-nine A.D.” Heady stuff, though he wasn’t exactly sure what it meant. There were other details hard to fathom, such as the Destriero’s unique ball-bearing-mounted “flying” tourbillon (eight vibrations per second) that was described as a kind of cage made of anti-magnetic, ultra-light titanium. The tourbillon was invented right after the French Revolution, its function being to improve accuracy by counteracting the earth’s gravitational pull on the balance.

The catalogue ended with a flourish. “Fin de Siěcle: The Grand Finale—This Is What Will Happen at Midnight on 31 December 1999. At precisely this moment, the most complicated wristwatch the world has ever seen will come into its own, as a multitude of functions start taking place simultaneously.” The final paragraphs walked one through the horological ballet, ending with the changing of the millennium guard. “A figure ‘twenty’ replaces the ‘nineteen’ in the date display of the II Destriero…and the twenty-first century since the birth of Christ has begun.”

Tovah called, wanting drinks at the Bel Air. He opted for breakfast at the Four Seasons instead—that felt safer. He wasn’t going to cry himself a river and he wasn’t going to fuck his brains out behind the cancer blues. Not his style.

What she proposed was a “special project,” a television movie about the remarkable life and death of his son, Montgomery. Perry felt trivialized, ready to be offended. Tovah stiffened. Then he laughed and the agent smiled.

“I hope it’s all right, my—”

“It’s fine. It’s fine,” Perry said, suddenly emotional.

“Rachel told me the story. I just thought it was so amazing.”

“And I wondered why no one ever—did anyone ask if you and Jersey—”

“I think Aaron and I talked about it. And Jim Brooks—we played a lot of basketball together. But I don’t think Jersey and I were up for it. It really took the wind out of us. The idea of revisiting…”

“I’m sorry—”

“No no no. Maybe it’s time,” he said, tapping his glass with a fingernail. “Maybe it’s been long enough.”

Ursula Sedgwick

“She’s not coming,” said Sara.

“Shit,” said Ursula, disappointed. “Why not?”

“Because,” said Phylliss, “I’m a crabby cunt.” She padded to the kitchen and retrieved a carton of Merits from the old Amana.

Sara Radisson was a casting agent who had worked on a movie of Phylliss’s that never happened. There was money from a divorce. After the split, Sara took the baby and lived awhile with her mom in Minnesota. It was a hard time; Phylliss was going through changes of her own. When the producer discovered Eckankar, she ordered Sara to visit the Temple of ECK, in Chanhassen—right near her mom’s place. Phylliss said that was no coincidence. There had to be a reason she wound up so close to the source.

Sara was a seeker. She found plenty of chelas, students of the Mahanta. She chanted Hu and was initiated on the Inner. One night, the ECK Master Rebazar Tarzs came to her in a dream and said it was time to stop running. The ECK Master (a pure blue light) said she should return to Los Angeles and complete unfinished business with two women she knew from a past life. When Sara awoke, Phylliss Wolfe and Holly Hunter hung before her like illuminated cameos. She got on the phone to Venice and the tears poured out in a stinging, soulful rush. Within a week, Sight Unseen had been sold to Lifetime, with Holly and Phylliss committing to star and produce.

“We know you’re a crabby cunt. But you still have to go.”

“I didn’t even hear about this thing.”

“I told you last week.”

“My womb is tired and bleeding.”

“So that’s it.”

“phyll thought she was pregnant.”

“By who?”

“Some Abbot Kinney bimbo.”

“Is it serious?”

“Of course, it’s serious. He’s a selected donor.”

“She means, selected at Hal’s—from the bar.”

“Is that safe, Phyll? I mean, has he been tested?”

“Yes, Mother. And I’m telling you,” she said, hands to crotch, “this model has got to go. If Larry Hagman gets a new liver, Phylliss Wolfe sure as shit wants a new womb.”

“Annie, Get Your Womb.”

“You need a transplant.”

“The girl from Baywatch.”

“No! From Friends—”

“Amateur hour, baby. I need me a professional womb, a Meryl Streep —Mare Winningham model, industrial-strength. I want me a litter.”

“How many does Meryl have?”

“Four, at last count. Mare has, like, twelve.”

“Meryl has four? I thought it was three.”

“Don’t quibble.”

“Come on, Phyll, please come.” Ursula rubbed her neck. “It’ll be fun. It’ll get you out of your mood. Pretty please?”

“You guys go. I just want to sit in bed and watch Bewitched. I have an inclination to see Dick York, pre—dementia.”

“Oh all right,” said Sara. “I guess someone has to baby-sit that big bratty uterus of yours.”

“Damn straight. And that’s ‘cervix’ to you.”

Ursula gathered up her things. “Tiff, do you want to come with us or do you want to stay with crabby Phylliss?”

“Go with you!”

“See?” said Phylliss. “Kids instinctively know to shun a barren woman.”

Sara asked if it was okay to leave her baby, and Phylliss insisted. “It’s high time,” she said, “that Samson bonded with Dick York. You know, a little imprinting couldn’t hurt.”

On the way to the ECK Center potluck, Sara talked about Sight Unseen. She was becoming another person, she said, and the book was part of that transformation. She talked about the divorce and what it was like to live with her mom again—the bond between mothers and daughters. Ursula reached back and grabbed Tiffany’s bare foot, almost the size of her own.

“Are you writing the movie too?”

“No way! We’re trying for Beth Henley—she wrote Crimes of the Heart. There is no way I could write a script. I could barely do the book!”

“Phyll’s writing one too, huh.”

Sara nodded. “We have the same editor. But Phylliss is going to have a best-seller—she’s a real writer. Mine’s just a compilation of letters.”

“It must be so exciting! Is Eckankar going to be in it?”

“I’d like it to be but…Phyll and I are kind of at loggerheads about that. I just want it to be universal. I don’t want critics saying there was anything—cultish, or whatever. I’m already thinking about critics!” She laughed, remembering how Phylliss said she wanted their “movie of the weak” to be special.

The Center was filled with kids and tons of Tupperware food. Sara pointed out seven H.I.s—Higher Initiates—those who’d been around ECK some twenty years and more. They were plain folk, down-home and grounded. Ursula talked to a writer who got turned on to ECK by his shrink, and a horse trainer from Rancho Cucamonga who married a non-ECKist. (He was into reincarnation, she said, so they got along just fine.) There was a shy young man with a bright smile—a boy, really—who looked a little ragged. Two of the H.I.s asked how he’d heard of the Center. Once they realized he was possibly homeless, they made sure his plate was full. Ursula was touched.

After a while, everyone sat in chairs and the cabaret began. The horsewoman read a poem about the Mahanta, then a trio sang songs about Light and Sound and Soul. The boy took a seat beside Ursula. A sticker on his shirt said HELLO, MY NAME IS TAJ. His knee touched hers and she moved it away, then moved it back. He smiled a bright, disenfranchised smile.

An H.I. who cheekily called herself “the Living ECK Master of Ceremonies” introduced a sketch called “Motorcycle Man.” A girl around Tiffany’s age slipped into a makeshift bed onstage. As narration began, a bearded, friendly-looking biker roused her. The girl brushed sleep from her eyes and climbed on his back while he revved the high handle of an imaginary Harley. “Now this girl was visited every night by the Motorcycle Man,” said the H.I., “and they cruised the city streets, then up to the sky. He told her many, many things. But every morning her parents wanted to convince her it was just a dream.” The upshot being that when the child grew up, she realized the Motorcycle Man was none other than a Living ECK Master. After the applause and laughter ebbed—the girl was a natural-born ham—the H.I. thanked “the father-daughter comedy duo of Calvin and Hobbes.” Everyone knew that “Calvin and Hobbes” was the Mahanta’s favorite cartoon. The sketch was taken directly from Sri Harold’s parables, she added.

The afternoon ended with everyone chanting Hu. “Gather your attention in the third eye,” whispered Ursula to the ragged boy. “Hold on to your contemplation seed.”

That night, Tiffany stayed with Phylliss. Ursula turned around and picked Taj up at the place she said she would, over by the Center. He was waiting there like a kid, after school.

They went to Bob Burns and listened to jazz. Taj ate some more. He’d pretty much been homeless the last few months, he said, begging for change outside Starbucks and the twenty-four-hour Ralph’s. She brought him back to United States Island and plunked him in a bubble bath. Then she lit the candle of her earthquake preparedness kit, slipped into a robe and put on Gladys Knight. Taj came to bed sopping wet, and she ran to get a towel to dry him off. He seemed perplexed, a dreamy colt, sweet and wobbly. He let her roll on a condom. She got on top, and when they were done, Ursula started to cry; she was thinking of Donny and everything, wanting out of her own skin. Taj got flustered. He said she was crying because of the transmitters in his mouth that made people sad when they kissed him. That scared her, but he laughed his bright laugh and she punched him. They wrestled awhile, then chanted Hu.

They lay side by side, listening to the carp of a cricket, close by. Suddenly, she was looking down, watching his tongue dig at her as she squirmed, arching back, hands trembling on the pommel of his head. The cricket was an omen that confirmed the fatefulness of this moment: just that day she heard Sri Harold talk on tape about the Music of God manifesting itself as flutes, chimes, buzzing bees—and crickets. Ursula was certain she’d met this boy in a past life. Sara and Phyll had a whole Victorian thing going, but Ursula sensed she and Taj went back much further. It would take some hard work on the Inner to find out just how far, but at least now the path was marked.

She shivered, lifting the boy onto her.

Severin Welch

Severin never strayed far from the Radio Shack scanner and its Voices. He picked his way through mines of static, listening to the agents and execs en route to power lunches; after midnight, pimps and drug dealers ruled. The choicer bits were duly recorded, then transcribed by his daughter, who still lived in the Mount Olympus wedding house on Hermes Drive. Lavinia made a meager living typing screenplays, and Severin was happy to throw some dollars her way.

The transcripts were returned and Severin pored over them, ruminating, sonic editor on high, scaling heights of cellular Babel, ducking into rooms of verbiage, corroded, dank, dead end—then a sudden treasure, odd heirloom, dialogue hung like chandeliers, illuminated. He held the sheaves to his ear and heard the dull, perilous world of Voices—the workday ended, seat-belted warriors homeward bound. All was well. Whereabouts were noted, ETAs demanded and logged, coordinates eroticized; half the world wanted to know just exactly when the other half thought it might be coming home. On the one-ten—kids there yet?—called you before—love you so much!—trying to reach—taking the Canyon—couldn’t get through—losing you…

Severin thought he recognized Dee Bruchner amid the welter. You tell that nigger, said the Voice, he closes at the agreed four million or I will spray shit in his burrhead baby’s mouth.

Had they always talked that way? He couldn’t imagine Mr. Bluhdorn coming on like Mark Fuhrman. Not to worry—he’d use it all to stitch one hell of an American Quilt. These were the Voices of a dying world, no doubt. They needed a script to haunt, and Dead Souls was just the place.

“You look awful,” she said, treading the doorway in a flowery perspiration-stained muumuu. Lavinia’s skin was oily white, an occasional pimple pitched like a nomad’s pink tent. She was turning fifty-three and wore a knee brace; the year had already added thirty pounds.

“Do you have my pages?”

“Do you have my pages! Do you have my pages! Don’t you say hello anymore?”

“Hullo, hullo!” He stood and did a jig. “Hul-lo, hul-lo—a-nuh-ther opening of a-nuh-ther show!”

She scowled, lumbering to the kitchen to fix a sandwich. Thank God Diantha wasn’t around for this. His wife had been so fastidious in her person, so immaculate—proprietary of her daughter’s fading beauty.

“Have you heard from Molly?” He risked a diatribe but couldn’t help himself. It was a year since he’d seen his granddaughter. Her birthday was coming up.

“Molly died, Father, remember? Molly died and Jabba took her place. That’s what she calls herself now—Jabba the Whore!”

He took the transcript from the counter and sat back down with an old man’s sigh. “Such a tragedy.”

“Since when is it a tragedy to be a whore?”

“Don’t, Lavinia. Don’t talk like—!”

“A whore and a doper. A jailbird, Father! She should die in prison, with AIDS!”

“Lavinia, she’s a sick girl.”

“I’m a sick girl! I’m a sick girl!” She pointed to a purplish knee.

“I’m in pain, Father, twenty-four hours a day. I didn’t choose that! Jabba the Whore lives in a world of her own choosing.”

“So do we all.”

“So do we all! So do we all!”

“That knee of yours is in bad shape because of the weight.”

“Oh, that is a lie and if you want to talk to my chiropractor, Father, he will tell you. So do we all, so do we all! Would you like me to call him?” Severin wearily shook his head. “You can talk to my acupuncturist too. And if you really want to know, which I’m sure you don’t, the weight on my knee is a cushion—”

“All right, Lavinia. It’s a cushion.”

“And the moral is! If you don’t know what the hell you’re talking about, don’t offer opinions! The great So Do We All has so many important opinions! God, do I hate that.”

They moved to Los Angeles in ‘forty-three and Severin bused tables at Chasen’s, working up to waiter. A quick, funny, ingratiating kid. He made his connections and eventually scored with the regulars, free-lancing bits for Red Buttons and Sammy Kaye. Then he met Hope and sold a few gags to the weekly radio show. They signed him full-time—but he’d always have Chasen’s. Took Lavinia there on her tenth birthday, still had the snapshot: slender girl in a party dress wedged between him and Diantha, George the maître d’ in his monkey suit on one side, Maude and Dave sidling in on the other, smiling from the blood-red booth like royalty. One of his old customers wheeled in the cake on a copper table—Irwin Shaw. He respected Shaw, a real writer, a book writer, that’s what Severin wanted to be in his heart of hearts. He tried and failed a dozen times before deciding to do the next best thing; adapt a classic for the screen. A novelist by proxy.

“And don’t you forget: Jabba the Whore was made from his seed.”

“Who?” he asked, riffling pages, not really listening. Severin tensed; too late—fell for it again. He was a player in a grim sitcom, a straight man in Lavinia’s little shop of horrors.

“Who! Chet Stoddard, that’s who!”

“Oh Christ—”

“Don’t you oh Christ, don’t you dare! For what that man put me through? Did you know that my jaw will never mend? Never mend: do you even know what that means?”

“It’s a long time ago.”

“Tell it to my jaw! Tell my jaw how long it’s been! I go to Vegas to rescue him and that piece of shit punches me out! At Sahara’s, right in the casino, hundreds of people!”

“All right, Lavinia—”

“Don’t all right me and don’t Oh Christ! The bone could have gone to my brain. Do you know what kind of headaches it has caused me? The migraines, Father? Do you understand how demeaning?” She began to weep. “With the pain and the police…the humiliation in that desert town. And not even jail, they dried him out in a luxury hospital, flew him back first class! If it wasn’t for me, his show would have gone off months before it did! I schmoozed for that man! With Saul Frake pawing me, his tongue in my mouth, I could vomit. Father? Would you please give me the courtesy of an answer?”

Severin poured himself a drink at the wet bar. He felt like an actor doing a bit of business.

“I’m a good person! Why has this happened to me? What has happened to my life? Why me, Father? Why! Why! Why!” She went to the bathroom and blew her nose while Severin sat down again to surf the bands. Lavinia re-emerged, waddling toward him with a fat rusty tube in her hand. “I took this from the drawer,” she said meekly. “Okay?” Some forgotten Coppertone cream. She seized the typed pages from his hand, brandishing them. He turned up the volume of the scanner. “What are you going to do with this? Your eyes are so bad you can’t even read. What are you going to do?”

“What do you care? You get paid.”

“People pay me to type for a reason, they have scripts, they have jobs, they’re writing books. I don’t understand your reasons—you’re just eavesdropping on people’s lives! People have a right to their privacy—”

“What are you, ACLU? You get paid to type. Period.”

“I’d love to hear what Chet Stoddard, the Larry King of his time, has to say—maybe you could listen to him. But he probably can’t afford a car phone. I hope he can’t afford a car or if he can, he’s living in it.” Her face lit up like a battered jack-o’-lantern as she threw down the pages and backed toward the door, Baggied sandwich in hand. “If anyone ever finds out you’re doing this—illegally eavesdropping—I want you to say you typed it yourself. Not that anyone would believe it. Just tell them you found someone else, not me, okay? All right, Father? Because I do not want to be drawn in.”

Free to listen to Voices again—shouting from canyons and on-ramps and driveways without letup, bungling into digital potholes on Olympic, dead spots on Sunset—shpritzing from palmy transformer-lined Barrington…Sepulveda…Overland…crying from electrical voids on nefarious far-flung PCH, dodging wormholes and power poles, festinating to beat devil’s odds of tunnel and subterranean garage as one tries to beat a train across a track—prayers and incense to ROAM (where all roads lead)—trying to beat the ether. A blizzard of Voices fell from range, chagrined, avalancheburied spouses in flip phone crevasse, electromagnetic wasteland of tonal debris. Neither Alpine nor Audio Vox nor Mitsubishi-Motorola could defend against unnerving fast food airwave static: recrudescent, viral, sudden and traumatic—words dropped, then whole thoughts, pledges, pacts, pleas and whispers, jeremiads—maddening overlap, commingling barked-staccato promises to reconnect swiftly decapitated: Westside loved ones morfed to scary downtown Mex, collision of phantom couples in hissing carnival bumper cars, technology cursed, torturous redial buttons pressed like doorbells during witching hour—hullo? hullo? can you hear me?—symphony of hungry ghosts begging to be let in.

I’m losing you.

Rachel Krohn

She sat in the lobby of the storefront mortuary, nervously thumbing a Fairfax throwaway. An ad within offered membership:

ONLY $18.00 A YEAR

· Free Teharoh (washing of body)

· Free Electric Yartzeit Candle

· Recitation of Kaddish on day of Yartzeit

Rabbinical-types in white short-sleeved shirts came and went without acknowledging her; she wondered if they were apprentices. A smiling Birdie brought her back to the cluttered office.

“Your father was not murdered.”

The old woman said it without preamble, like a teacher delivering a Fail.

“What are you saying?”

“Forgive me—but something in my heart told me it wasn’t right to hide what I know. I thought it was God putting me next to you at the seder.”

Rachel was dumbfounded. For a moment, she wondered if Birdie was someone in the grip of a religious psychosis. “What do you know? What happened to my father?”

“Your father took his own life.”

Rachel let out a great sob. The old woman touched her, then withdrew. She handed her Kleenex and a cup of water, then calmly spoke of Sy Krohn’s affair with a congregant—how the “lady friend” gave him a disease (“nothing by today’s standards!”); how the cantor, realizing he’d passed the infection to Rachel’s mother, chose to die.

“You said…your husband was there?” She spoke as if reading a script from a radio show. Your father was not murdered—Orthodox film noir. “You said at the seder—”

“Here—the body was flown back. But you know that.”

“But your husband…”

“He performed the taharah.”

“May I talk to him?”

“He will not speak to you. He was opposed to me telling what I knew.”

“Was it here that he—” The old woman nodded, and Rachel thought she would faint; this is where the body had lain. She stood, as if to go. “You said those who do the…purification—are volunteers. Is that something I could do?”

“It’s not for everyone.”

Rachel shook, flinching back tears. “But it’s for me!” The words came savagely, humbling the shomer. Rachel composed herself and said again, softly: “It’s for me.”

Birdie walked her to the sidewalk.

“You’ll call?”

The old woman nodded. “I will.”

“There’s just one other thing I wanted to know. My father’s buried at Hillside. How is it—I thought if a Jew killed himself, he couldn’t—”

“There are ways around that. It was simply said your father was not in his right mind. Which he was not.”

As she reached her car, Rachel imagined a string of women in the lobby, pending on Birdie—each with a revelation waiting, custom-made.

Sy Krohn was buried in the Mount of Olives on the outskirts of the park, across from a large apartment complex. On her way to the plot, Rachel tried remembering details—but that was thirty years ago. A worker on a tractor respectfully cut his engine as she stood over the stone. She was certain it was park policy; he even seemed to hang his head. BELOVED HUSBAND AND FATHER was all it said.

Rachel wasn’t ready to confront her mother, so she drove to the mansion overlooking the necropolis. That’s where the rich were interred—far away from the syphed-out cantor-suicides. Al Jolson’s sarcophagus adorned the entrance. “The Sweet Singer of Israel” knelt Mammy-style while a mosaic Moses held tablets in the canopy above. Mark Goodson, game show producer, was across the way, the outline of a television screen around his name.

No one was inside but the dead. Scaffolding stood here and there in the hallways, as if the artists painting the ceilings were on lunch break. Small rooms off the main drags were filled with stacks of thin green vases. A few employees loitered outside, tastefully—they seemed aware of her browsing, and again, she wondered if by policy they’d left their workaday posts, awaiting completion of her tour. She entered an elevator as if it were a tomb and rode to the second floor. More couches and vases and yarmulkes and emptiness. She took the stairs down, past the David Janssen crypt. There were flowers and a big birthday card signed Liverpool, England. “We cry ourselves to sleep at night,” it said. “We will never forget you.” She passed vaults of “non-pros” with strangely comic epitaphs: HIS LIFE WAS A SUCCESS; SHE LIVED FOR OTHERS. Then came Jack and Mary Benny, and Michael Landon. “Little Joe” had a room to himself, with a small marble bench. The entrance had a glass door, but it wasn’t locked. Anyone could go in.

“Who told you this?”

They stood in the hot, bright kitchen. The psychiatrist was between clients.

“What difference does it make? Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I planned to,” said Calliope. “At the time, there were so many other things…I was going to wait until you were a little older, but then—”

“Well, now I am!” A mocking kabuki mask, glazed with tears.

“Do you really think you would have wanted all the details, Rachel? Could you have handled them? Can you handle them now?”

“Don’t insult me, Mother.”

“Is it any better now that you know?”

“I’m glad I know the truth.” A door opened outside. Mitch and a patient said goodbyes. “It’s so…classically hypocritical! The old cliché, isn’t it? The psychiatrist who tells her patients that secrets kill—and here we are, all these years, living a lie! Can’t you see how insane that is?”

Calliope whitened, trembling. “Your father was the hypocrite, not I! What I did, I did for you, Rachel, to protect you, you and Simon. If we had stayed here, believe me you would have been hurt. So don’t talk to me about hypocrisy.”

They heard footsteps. Mitch returned to his office. The women caught their breath, and Rachel resumed in subdued tones.

“Do you—do you know who the woman was? Is she still…”

“Serena Ribkin. She died last year. She happened to be the mother of a client, strangely enough.” She sat in the banquette, limp. “There: now you even have a name.”

“Was…was my father in love with her?”

“I imagine. Such as love is—though I doubt it would have lasted. But what the hell do I know? Maybe they were Tracy and Hep.” She stood, energized again; her mother was always a quick recovery. “Rachel, I have to get back. Why don’t we have a nice dinner over the weekend—we need that. We can go to that fabulous sushi place on Sawtelle.”

“All right, Mama.”

She fell into Calliope’s arms and wept. Mitch was suddenly at the back door, but the psychiatrist sent him away with a shake of the head.

“That was a terrible, terrible time—you’ll never know, darling, you don’t want to. You and Simon were away, remember? I was glad of that. I used to literally thank God for Camp Hillel.”

She stroked her daughter’s head and kissed it. And then she cried and Rachel couldn’t remember seeing that, ever. Her hair was thick and gray; at sixty-seven, she was still a beautiful woman. They strolled to the front door, arm in arm.

“Who was it that told you about your father?”

“A woman I met at a seder.”

“You went to a seder?” She smiled, genuinely surprised.

“At my boss’s.” Rachel wasn’t sure why she lied. “I had to, for business.”

“And who was this woman?” Calliope asked, a paranoid glint in her eye. “Is she talking to people about Sy?”

“Not at all—Mother, it’s nothing like that. It was an isolated event, a weird thing. She didn’t even know who I was.”

“She didn’t know who you were yet ends up telling you your father killed himself. Very mysterious.” Calliope smiled indulgently. There would be no more interrogations, at least not today. “Well,” she said, kissing her daughter again, “you go home and soak—take a bubble bath. I’ll call and we’ll make a time.”

Severin Welch