6. Mysticism, Despair, and Progress

George Sand’s Pursuit of Religious Liberty

George Sand sought spiritual direction from Lamennais in 1835 at a particularly difficult moment in her tumultuous life. In October there had been violent scenes between Sand and her husband at their estate at Nohant about the terms of their separation, and she had recently broken off her affair with the poet Alfred de Musset and become attached to the republican lawyer Michel de Bourges. This new liaison had pulled Sand deep into debates about political and social conditions in France, for Bourges was at the center of the team of lawyers defending the workers of Lyon who had rebelled in April 1834. All of these changes in her life were accompanied by religious anxieties, as she sought a form of belief that would accommodate her sense of personal freedom, her political beliefs, and her Christian mysticism. Sand had already become famous for her novels, starting with Indiana, which appeared in 1832, but the accumulation of personal and political troubles left her in a state close to despair.1 The friendship between Sand and Lamennais that began in this period of their lives endured, but both soon passed beyond an initial phase of mutual respect that bordered on sycophancy. By May 1836 Sand was writing to her friend Marie d’Agoult that Lamennais was “much more of a priest than I thought.” Lamennais’s prophetic vision of a democratic future remained appealing, but she resented his dogmatism and insisted that “on that point I claim a certain freedom of conscience which he would not grant me.”2

Sand’s declaration of independence is not surprising, for she is known as a woman who boldly challenged the conventions of her time, leaving her husband, engaging in a series of very public love affairs, dressing like a man, smoking cigarettes, and defending radical political and social ideas in her voluminous writings. In a recent biography Elizabeth Harlan suggests that beyond such “commonplaces” Sand’s life should be understood as “a ceaseless production of acts and works undertaken on behalf of the principle of freedom to which she remained committed throughout her life.” Harlan’s focus on a universal principle provides a useful perspective from which to view a life full of scandalous detail, but in her litany of the kinds of freedom Sand pursued (“personal, social, political, creative, professional”) she leaves out her concern for religious liberty, for the right to define her own views on God and his relationship with mankind.3 This quest, however, is clearly on display in Sand’s correspondence and imaginative writing, and in the autobiography she wrote in her forties, evidence that allows us to trace a complicated religious journey from an unorthodox education as a child, to a mystical Catholicism while an adolescent, to a form of social Christianity as an adult. As did Lamennais, Sand saw the struggle to create a better world as a sacred obligation, but her personal history, with its disastrous marriage and passionate love affairs, reveals a different path to religious liberty. For Sand, female subservience to men, especially within the illegitimate bonds of contemporary marriage, became a central theme in her life and work, issues that were pushed aside by Lamennais as irrelevant. But Sand’s life and writings show that her commitment to the rights of women evolved in intimate connection with a growing sense of individual religious liberty, a freedom she embraced in both her life and her literature.

Aurore Dupin Invents a God

Since no one was instructing me in religion, it occurred to me I needed one, and I made one for myself.

—George Sand, History of My Life

Liberty of conscience was central to Sand’s religious identity, but she came to a conscious recognition of this principle only after a remarkable religious journey that began when she was a child, creating a private religious world in the gardens of her Voltairean grandmother’s estate in Nohant, in Berry. Aurore Dupin, as Sand was named at birth, was the daughter of a French officer, Maurice Dupin, and his wife, Sophie Delaborde, a demimondaine regarded with suspicion, and at times outright hostility, by Maurice’s mother, Mme Dupin de Francueil, the granddaughter of the great general Maurice de Saxe. The tense family atmosphere became more pronounced with the death of Sand’s father when she was four, which led to a decision that her grandmother would take primary responsibility for her upbringing. Placing Sand with her grandmother had religious consequences, for while her mother was conventionally devout, Mme Dupin was a religious skeptic, though her aristocratic status and memories of the revolution led her to respect Catholicism as a basis for social order. Sand’s grandmother and various clerical tutors shaped an atmosphere that mixed belief and skepticism and provided her with a sense of religious liberty throughout her childhood, experienced as an ambivalent context rather than as a systematic principle.

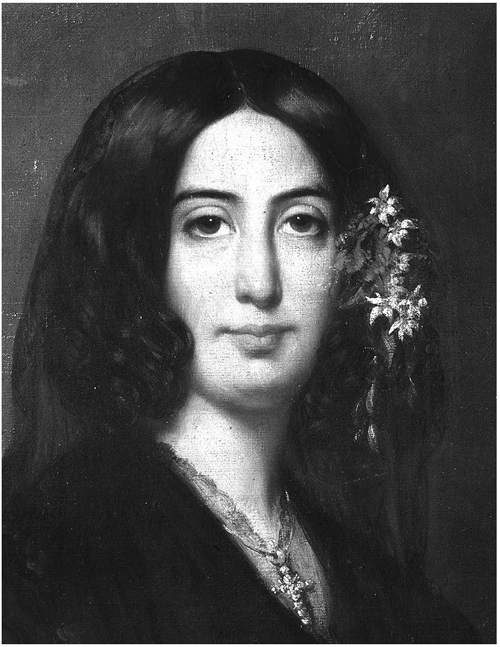

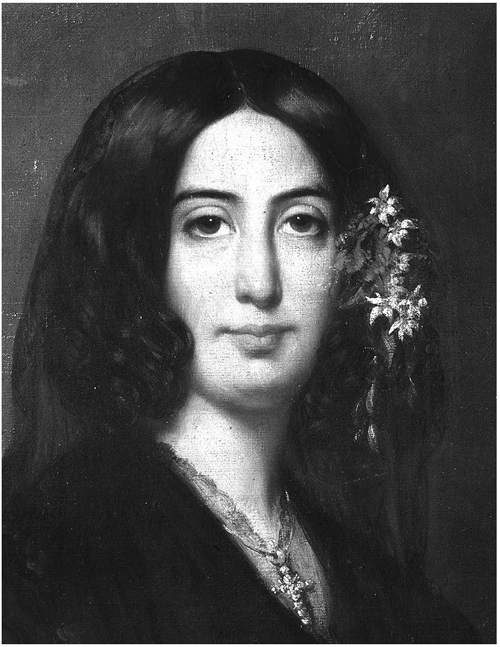

Figure 9. Portrait of George Sand by Eugène Charpentier, 1835. Musée Carnavalet, Paris. Gianni Dagli Orti/ The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

Although she was born a generation after Lamennais, like him Sand’s earliest education had little connection with the kind of catechetical training in religious orthodoxy that had become an ideal of the Old Regime but was only slowly and partially reestablished following the Concordat of 1801.4 Sand was educated at her grandmother’s estate by François Deschartes, a clergyman during the Old Regime who abandoned his vocation and clerical title in 1789 to become the tutor of Maurice, Sand’s father. During the Terror Deschartes played a key role in saving Mme Dupin from the guillotine, and he stayed with her as a devoted member of her household when she purchased the estate in Nohant after her release from prison. Known to the family as “the great man,” Deschartes was, like Sand’s grandmother, a religious skeptic who nonetheless believed in following conventional practices.5 Sand’s great-uncle, the abbé Charles-Godefroid de Beaumont, provided another example of how religion, and even a clerical identity, could be molded into a pattern that accommodated personal choice. An amiable storyteller and gourmand, Beaumont entertained Sand and her family at his Paris apartment and visited them frequently in Nohant. Sand recalled him fondly as “a cheerful character, a bit carefree, as some bachelors are, a remarkable wit, resourceful and inventive.” While a source of advice and friendship, the good abbé was not at all devout but was preoccupied with food and conversation; Sand described him as a “canonical type that has practically disappeared in our time.”6

Sand was not trained in Catholic orthodoxy, but she did develop a powerful religious sensibility, a disposition to believe and worship that was to take on a variety of forms as she matured, even while she also struggled against doubt and despair.7 Around the age of eleven, inspired by her reading of The Iliad and Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered, Sand began constructing an elaborate personal religion, centered on her fantastic invention of a god or goddess that she called Corambé. These epics of heroic warfare, with gods and men contending with each other, and with themselves, fired Sand’s imagination and inspired a childish form of religious syncretism. In Tasso’s poem Sand read about Clorinda, a woman both passionate and devout, a Muslim warrior who accepted baptism as she died on the battlefield, having been slain by Tancred, the Christian knight who had fallen in love with her. Sand’s fond memories of Jerusalem Delivered suggest the profound impact of a story that combined romantic passion, feminine bravery, and religious fervor manifested in a dying conversion.8

Corambé, as recalled in Sand’s autobiography, was a spirit of peace and reconciliation, a god or goddess “as pure and as charitable as Jesus,” but embodying as well “nymphic grace and Orpheus’ poetry.” Corambé was a literary muse as well as a sacred figure, a character who inspired what Sand called “songs” that described how the god or goddess charmed and consoled those who suffered, “listening to their tales of woe and leading them back to happiness through virtue.” More and more absorbed by her musings, Sand eventually built a secret shrine to Corambé in a thicket of woods on her grandmother’s property. Retreating to this spot in the afternoons, when her lessons were suspended for two hours, Sand decorated it with flowers and shells and for her ritual would free birds from the snares she had used to capture them. After a month or so, however, some of the local peasant children, Sand’s playmates, discovered her hiding place. “The spell was broken,” she recalled, and she abandoned her shrine, though not her devotion to Corambé, carefully burying the garlands and shells under the debris of the altar.9

During the time that Sand was creating Corambé and exploring a religious world of her own making, Mme Dupin decided it was time for her granddaughter to make her First Communion. But Sand’s preparation for this sacramental initiation was far from orthodox, given her grandmother’s rejection of transubstantiation, the doctrine that insists on the real presence of Christ in the consecrated host. For Mme Dupin, this was “superstition,” as were all the miracles recounted in the gospels; she insisted nonetheless that Sand “go through this ceremony with decency and for appearances’ sake, but to be careful not to offend divine wisdom and human reason to the point of believing I was going to ‘eat my Creator.’”10 Sand’s catechetical instruction was crammed into three short weeks, which she accepted with docility and mastered quickly. On the chosen day Sand was shocked to see her grandmother in church, where she had not set foot since her son’s marriage, more than twenty years in the past. In her autobiography Sand claims that she reconciled herself to the apparent hypocrisy of her performance by imagining the Last Supper as a celebration of equality and charity. On this point Bernard Hamon suggests that Sand might be projecting into her childhood an interpretation of the Eucharist beyond the capacity of even a precocious twelve-year-old.11 This is a reasonable perspective, but so is Hamon’s more general sense that in her autobiography Sand describes a rich and confusing religious formation that left her in search of a God of infinite goodness with whom she could form an intimate personal relationship. Though it would prove to be a phase rather than a permanent commitment, during her adolescence, Catholicism fulfilled this religious need.

Convent School and Catholic Conversion

As a child Sand was precocious and adventuresome, but her grandmother was concerned that she was also undisciplined and lazy and as an adolescent would need to acquire the polish appropriate to a young woman with an aristocratic lineage. During the revolution Mme Dupin had been imprisoned for a time in a convent of English nuns in Paris, a congregation that established a boarding school for elite girls during the Restoration.12 This establishment became Sand’s home for three years, a period of time when she saw her grandmother, mother, and other relatives only rarely. Sand’s vivid memories of her years in this cloistered community are the basis for some of the most fascinating pages in her autobiography, where she recounts her transformation from mischievous troublemaker to devout young woman, converted by a mystic experience and convinced that she had a religious vocation.13

The couvent anglais that was home to Sand from 1818 to 1820 was shut off from the life of Paris, recalled by her as “quite truly a prison, but a prison with a big garden and numerous companions.” But Sand did not suffer from these apparent restraints on her freedom and insisted that “not for a moment did I experience any of the rigors of captivity, and the meticulous precautions that were taken to keep us under lock and key and prevent our having even a glimpse of the outside world only struck me as funny.”14 André Maurois has suggested that convent life, although full of external constraints, offered Sand an “oasis” where she no longer felt herself a source of conflict between her mother and grandmother.15 In her autobiography Sand develops a paradoxical view of the monastic setting as a prison-like atmosphere within which she was nonetheless free to explore spiritual possibilities and change her religious identity, a perspective that shapes her metaphysical novels of the 1830s, Lélia and Spiridion. As we will see, these works include sharp criticisms of orthodox Catholicism, reflecting Sand’s anticlerical views of monasteries as tyrannous and cruel institutions. But her hostility is shaded by a competing sensibility that saw in a cloistered life the opportunity for quiet reflection and study and a community that would support rather than repress the aspirations of its individual members.

Upon entering the convent Sand was at first placed with the lower of two classes, where she quickly decided to join the “devils.” The young girls in this group were determined to be troublemakers, which meant for the most part annoying their teachers with harmless juvenile pranks, passing notes to each other, sleeping through catechism, and mocking Miss D., a lay teacher despised for her strict religiosity and meanness. But the devils had a grander mission as well, and starting in her first days in the convent Sand joined their regular nighttime outings to free female prisoners they imagined were held somewhere in the underground passages or obscure hallways that honeycombed the convent.16 Although Sand writes that she and her friends “convinced ourselves that we heard sighs and moans coming from under paving stones or issuing from the cracks in the doors and walls,” these nightly expeditions were essentially a form of play, but what did the game mean? In her autobiography Sand recalls “this mania for seeking the victim [as] something profoundly stupid and also heroic; stupid, because we had to suppose that these nuns, whose sweetness and goodness we adored, practiced some frightful torture on someone; heroic, because we were risking our lives every day to liberate an imaginary being.”17 Sand’s comment points to an absurd quality of the game, but perhaps she is too quick to dismiss it as “profoundly stupid.” As Sand realized, in their play the girls were acting out a prominent theme in the fashionable gothic literature, which featured heroes and heroines imprisoned in the dark recesses of monasteries.18 The nuns of the convent may have been generally beloved by the girls, but as Sand pointed out they were also their wardens, enforcing a life separated from the world in which cold and hunger were not unusual and punishing them when they broke the rules. The popularity of gothic novels and plays in which monks and nuns locked away innocent victims drew on a broader anxiety about the potential for repression in Catholic congregations, and in the church more generally. Sand and her friends were engaged in a childish fantasy, but one that tapped into both personal experience and a cultural mood in which individuals were called on to act heroically to gain their freedom from the Catholic Church.

Sand pursued her career of “deviltry” during her first year at the convent, but she also sought advice and consolation from Sister Mary-Alicia Spiring, a young woman admired by all the girls for her beauty, warmth, and authentic piety. To the surprise of the other devils, Sand asked to be “adopted” by Sister Alicia, and they were even more surprised when she accepted Sand as her daughter. This special relationship allowed Sand to spend a few minutes every evening with her mentor, who was more amused than troubled by her childish behavior, which led to good-humored reprimands. Sand would return to her room afterward, “bearing, as if by magnetic influence, some of the serenity and candor of that beautiful soul.”19

Sand’s decision to seek the support of Sister Alicia was followed in her second year by her abandonment of the devils, though she also refused to identify with the “sages,” the good girls whose ostentatious piety annoyed her. In her autobiography Sand recalls her conversion in terms that echo in many ways Augustine’s famous Confessions. Writing in the 1850s, Sand drew on her knowledge of Augustine, and she likely embellished some details and smoothed out the narrative of her conversion to make it accessible to her audience.20 Her autobiography is nonetheless precious evidence, reflecting her adult conviction about the reality of the spiritual transformation of her youth and offering some sense of how it involved both her own will and the rich and mysterious religious environment of a Catholic convent.

“I became religious. It happened suddenly, like a passion that ignites in a soul unaware of its own powers.” Sand’s language as she begins the account of her conversion suggests it was the result of her own volition, but also of a mysterious process that occurred below the level of consciousness. The “devils,” like all the girls, were required to spend a half hour in the chapel each evening, and to pass the time Sand began reading an abridged version of The Lives of the Saints that she found in the pews. While skeptical about the miracles in these stories, Sand admired “the faith, courage, and stoicism of the confessors and martyrs,” which “plucked some secret string that was beginning to vibrate in me.”21 During these evening visits Sand also began to observe two paintings in the chapel, one showing Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane, where he prayed that God might spare him from his death, foreseen for the next day, and the other representing Augustine at the moment when he heard the words “Tolle, Lege” (“Take up and read”), which led him to the Epistle of Paul to the Romans and then to his conversion.22 Contemplating the image of Christ, Sand found herself in tears as she attempted to understand the meaning of his death, “the secret of his chosen, yet so bitter suffering,” and she “began to have a presentiment of something grander and more profound than what I had been told.” The painting of Augustine led her to the story of his conversion, to the epistles of Paul, and to the gospels, which she read attentively for the first time. All of this reading and reflection, however, was merely a prelude to the revelation that finally led Sand to a serious commitment to Christianity, and a possible vocation.

In her second year at the convent Sand had moved toward Christianity, but without abandoning her devilish identity. One evening she decided to sneak into the chapel so she could observe an old hunchbacked nun at prayer and then describe “how the little monster writhes on her bench” to her friends. But once inside, the nun disappeared, and Sand lapsed into a reverie, entranced by the single sanctuary light and the nuns who prayed and left, until she was alone. Sand recalls this moment in her autobiography:

I was oblivious to everything. I did not know what was happening to me. I was absorbing an atmosphere of indescribable sweetness more through my soul than my senses. Suddenly my whole being was mysteriously shaken, a whirling whiteness passed before my eyes on the way to surrounding me. I thought I heard a voice murmuring in my ear, “Tolle, lege.” I turned around thinking it was Marie-Alicia speaking to me. I was alone. . . . I felt simply that faith had filled my being and that it had come to me, as I had hoped, through my heart. I was so grateful, so ecstatic, that tears streamed down my face. I again felt that I loved God, that my thought embraced and accepted fully this idea of justice, tenderness, holiness that I had never doubted, but which had never touched me directly; finally, I felt a direct bond, as if the insuperable obstacle that had stood between the hearth of infinite warmth and the dormant flame in my soul had been swept away.23

Moved profoundly by this mystical experience, Sand abandoned her devilish ways entirely, began receiving communion regularly, and took up ascetic practices, such as wearing a rosary around her neck, which cut her and made her bleed. She became close at this time with a lay sister, Hélène, one of those charged with the manual labor of the convent, and through her influence decided she had a religious vocation. This sudden transformation was regarded with some sarcasm by her former friends and was naturally welcomed by her teachers. But Sand was careful to note that the nuns did not try “to augment my fervor by any of the seductive means that religious communities are accused of exerting on their pupils.” And she was particularly grateful to her confessor, the Jesuit abbé de Prémord, who ordered her to stop her pursuit of moral perfection through an overscrupulous examination of conscience and an ascetic lifestyle that was damaging her health. Both Prémord and Sister Alicia also expressed reservations about Sand’s vocation and warned her against taking premature vows. In recalling her convent years thirty years later Sand remained grateful to her mentors, who refused to take advantage of her conversion to entice her into a religious life. Their advice was based on a conviction that only a mature individual could freely choose to pursue a vocation, and thus they affirmed the principle of personal religious liberty. As we will see, Ernest Renan found a similar atmosphere of freedom while a student at the seminary of Saint-Sulpice in the 1840s. Sand would eventually abandon Catholic belief and practice, and she adopted as well many of the standard positions of anticlericalism that saw the Catholic Church as an intolerant institution based on superstition and opposed to reason. During the 1820s she grew into a young woman increasingly confident in her independent religious judgment, skeptical about Catholic doctrine, but still tied to Catholic practice and to clerical advisers whose ideas she valued. This complex position was based on the early freedom she experienced in the gardens of her grandmother’s estate at Nohant, but also on the combination of fervor and freedom she found in her Paris convent.

Family Troubles and Religious Exploration

When her grandmother learned of Sand’s turn to religious devotion she decided that her charge had spent enough time with the nuns and brought her back home to Nohant in the spring of 1820. For the next ten years Sand’s life revolved around the estate, and her increasingly complicated family situation. In exploring this period Sand’s biographers have focused on her unhappy marriage to Casimir Dudevant, the birth of her two children, and the first of her many extramarital affairs. These personal dramas became in turn material that shows up transformed but still recognizable in the literature that Sand produced in the 1830s. But the evidence Sand has left us reveals as well a sustained concern with religious questions, an evolving sense of her relationship with Catholicism, and a growing appreciation of her religious liberty. Sand is best known for her rejection of traditional marriage as an oppressive institution in which husbands exercise an illegitimate authority over wives, but her disillusionment with conventional family life developed in close conjunction with her increasingly critical view of orthodox religion. The freedom that Sand pursued brought her up against the institutions of marriage and the Catholic Church, a struggle that led her eventually to abandon both and that allows us to see through the prism of an individual life the close links between religious liberty and the quest for personal autonomy.

The fullest account of Sand’s religious evolution in the 1820s can be found in her autobiography, where she describes the books, discussions, correspondence, and reflections that transformed her from a pious Catholic schoolgirl to a religious doubter. After her return to Nohant Sand was left free to read in her grandmother’s extensive library, where she began a program of self-education that recalls Lamennais’s experience amid his uncle’s books a generation earlier. On the advice of her confessor, the parish priest of La Châtre, the town just south of Nohant, she read Chateaubriand’s Génie du christianisme, which rekindled her spiritual life but also taught her to consider Christianity as aesthetic experience and moral guide, and not as a doctrinal cage. Early in her return to Nohant Sand also reread L’imitation du Christ, in a copy given to her by her beloved Sister Alicia, which she now saw as a text preaching hostility to the world and to human connections. This book of “abominable selfishness . . . commanded me to forget all earthly affection, banish all pity from my breast, break all family ties, have only myself in view, and leave all others to God’s judgment.”24 Sand recalled as well being moved by Leibniz’s insistence that “true piety consists of God’s love, but an illuminated love, whose fervor is accompanied by enlightenment.”25 But unsurprisingly it was Rousseau, “man of passion and feeling par excellence,” who had the most profound effect on Sand. After reading Emile, Les lettres de la montagne, and Le contrat social Sand recalled that “I understood everything!”26

Through Chateaubriand and Rousseau Sand was drawn to a romantic Christianity of the heart, to a God who could be approached through nature as well as the sacraments, and who discounted the doctrinal differences between Protestant and Catholic. But how did this emerging religious sensibility fit with the orthodox Catholicism that she had absorbed while at the couvent anglais? Sand wondered herself about this question, to which she gave an equivocal answer that suggests how hard it was for her to state clearly what her religious convictions were as a young woman: “Was I still Catholic the moment when, having saved the best (Jean-Jacques) for last . . . I was finally to fall under the spell of his touching reason and fervent logic? I do not think so. While still practicing the religion, still refusing to break from its formulas interpreted in my fashion, I had left, without my least suspecting it, the confines of its orthodoxy. Unknown to myself, I had broken irrevocably with all its social and political conclusions. The spirit of the Church was no longer in me; perhaps it never had been.”27 Sand here describes an in-between state not unlike the uncertainty we have seen in other converts as they moved across the borders around Catholicism. Sand’s retrospective denial of her Catholic identity in the 1820s may overstate the extent of her alienation from the church at the time. As she acknowledges in her autobiography, she continued to practice Catholicism regularly, she stayed in touch with her religious advisers from her convent days, the abbé de Prémord and Sister Alicia, and she was in regular contact as well with the local clergy. But we can still respect Sand’s mature judgment that she had moved some distance from orthodoxy without fully realizing it, a pattern common to other converts as well. Nonetheless, friends and family would have had no reason to doubt Sand’s Catholicism, even if she also showed herself to be an independent-minded and temperamental young woman.

Sand’s behavior in the period surrounding the death of her grandmother, Mme Dupin de Francueil, in December 1821 illuminates the complexity of her attachment to Catholicism, which combined a commitment to the authority of the church and the grace available through its sacramental system with a respect for the individual conscience. Still a very young woman, only seventeen years old, Sand helped nurse her grandmother through a long and debilitating illness for most of the year. As her condition grew more serious, Sister Alicia encouraged Sand to convince Mme Dupin to receive the Last Sacraments, while the abbé de Prémord took a more tolerant position, writing to her that “[to] take the initiative in the delicate matter of her conversion would have been contrary to the respect that you owe her.”28 The situation was complicated by the arrival at Nohant of M. Leblanc de Beaulieu, who had recently retired as the bishop of Soissons. Leblanc was the illegitimate half brother of Mme Dupin, the son of her father and Mme d’Epinay, the famous Paris salonnière of the eighteenth century. Sand described him as well-meaning but fat, oafish, and vain. Leblanc was grateful to Mme Dupin, whom he addressed as “Dear Mama,” for her solicitude during his childhood and was determined that she die with the sacraments and thereby avoid eternal damnation. When Mme Dupin asked if Sand shared her uncle’s fears on her behalf the granddaughter insisted that “I am on my knees to bless you, not to preach to you.” Moved by this act of confidence, but also willing to accommodate her half brother and continue to follow religious conventions, Mme Dupin received the Last Sacraments from the parish priest the following day. But the ceremony was conducted with her characteristic sense of irony toward orthodox Catholic practice. As the priest went through the prayers she would comment, “I believe in that” or “that is meaningless,” while Archbishop Leblanc pretended not to notice. In her autobiography Sand sees this episode as marking her own movement to a more relativistic understanding of Catholicism, a comment that seems fair, especially in light of her intellectual development, which paralleled the period of her grandmother’s illness and death. Sand was not a self-conscious advocate of religious liberty in the early 1820s and was still some distance away from a clear break with Catholicism. But in her reading and in her family life she was testing religious boundaries and, without fully realizing it, exploring the condition of religious freedom that would eventually become a central theme in her writing.

The birth of Sand’s first child, Maurice, in 1823 and a busy schedule of visits to Paris, to friends in the countryside, and to the Pyrénées for an extended vacation were not enough to distract Sand from some harsh truths about her husband and her marriage. Following the death of her grandmother, and in order to escape the control of her mother, who sought to reestablish her authority over her daughter, Sand rushed into a marriage with Casimir Dudevant. Although a man of some personal charm, Casimir had no interest in ideas and was devoted to the hunt and to hard drinking, much of it done in bouts with Sand’s half brother Hippolyte, who was an almost constant presence at Nohant. Sand’s troubles with Casimir, and her exhaustion from caring for the baby Maurice, led to a depression that she attributed as well to “the almost imperceptible cooling of my religious faith.”29 On the advice of the abbé de Prémord, Sand returned to her convent in Paris for a retreat early in 1825 that she hoped would restore her faith. Living again at the scene of her adolescent devotions provided some relief. Both she and Maurice, who was given the special privilege of being allowed into the cloister, were spoiled by the nuns, and Sand was consoled by Sister Alicia, who praised the advantages of married life and motherhood. Sand thought again about the appeal of the quiet life of a cloistered community but left hurriedly when Maurice seemed to fall ill. The retreat did not bring Sand back to the fervor of her adolescence, but it illustrates her continuing desire to explore her religious beliefs and feelings, which were about to face a major challenge in the person of Aurélien de Sèze.

As the many biographers of Sand have pointed out, her alienation from Casimir led to several flirtations and, in the mid-1820s, to a serious love affair. Sand met Aurélien de Sèze during their trip to the Pyrénées in 1825, and for the next five years their love for each other made for an extraordinarily complicated life, a first chapter in her long and well-chronicled history of amorous intrigue.30 During the early stages of their romance Sand made it clear that she intended to stay faithful to her husband, even while admitting her passionate love for Aurélien. In a long series of letters written to her lover in October and November 1825 Sand poured out her heart, reflecting on their time together, and the combination of joy and pain she experienced in contemplating their impossible situation. Sand’s insistence on marital fidelity was tied to religious sentiments that are threaded into the letters, a motif that made God into a third party in her relationship with Aurélien.31 Sand concluded one letter, for example, with a prayer in which she begged God to “bless our union, purify it, perfect it, to the point that you might see it with pleasure, and root out anything that might be impure and imperfect. My God, my God, make me worthy of you.”32 On another occasion Sand anticipated a heavenly reward for the virtuous lovers: “Let us believe that this dust will live again, that the Eternal who created it will be able to bring it back to life. He will be grateful to us perhaps for having born with a life that was nothing for us without each other. He will reunite us forever then, in a state of peace, where tenderness will be allowed and happiness will last.”33

The future blissful state that Sand foresaw was very far from the trouble that followed from Casimir’s discovery of her journal, which contained several letters to Aurélien. Sand insisted that this correspondence gave no evidence of infidelity, but Casimir was understandably furious and their marriage was in serious jeopardy. This crisis was resolved, at least for a time, on the basis of Sand’s “lettre-confession,” an eighteen-page document she sent to her husband on November 15, 1825. Sand made no apologies for her feelings for Aurélien, claimed the right to continue her relationship with him, and asked that Casimir accept him as a friend. Thus began a triangular platonic relationship that, at least for a time, seemed to satisfy the interests of the three parties involved. The November letter marks a turning-point in Sand’s life; the longest she had written to that point, it included a forthright account of Casimir’s failings and the problems in their marriage and established her own clear conditions for their staying together. Less than a full declaration of female and wifely independence, it was nonetheless a move toward greater openness and freedom within marriage.

Just one month after her “lettre-confession” to Casimir, Sand wrote another remarkable and lengthy letter, this one to Zoé Leroy, a close friend from Bordeaux who had facilitated her relations with Aurélien.34 Encouraged by Casimir’s willingness to accept her conditions for their marriage, Sand expressed her absolute confidence in “this all-powerful Being” and criticized as unjust those who “would not place their hopes for happiness entirely with him.” This confidence in a loving God was followed by an extended analysis of a local controversy over a recent conversion that had led the abbé Cyprien Pouget, the curé of Nérac, to publish a letter condemning M. and Mme Dumont, a couple who abjured Catholicism in favor of Protestantism.35 Their decision and the curé’s response were the talk of the region; Sand reported that “nobles and dévots” criticized the Dumonts, while liberals found fault with the abbé Pouget for publicly castigating a couple who were well regarded in their community. Sand found the priest’s pamphlet full of “commonplaces, useless comments, unjust reasoning, and crude exhortations that neither persuade nor move.” Her comment about Pouget led into a more general condemnation of the clergy whose conduct brought religion into disrepute: “Is it not a subject of sadness and continual bitterness to see a sublime religion degraded, reviled, ridiculed because of its ministers, by those who should make it cherished and respected? . . . How unworthy are those at the top of the hierarchy, who confer a sacred character on a drunkard, a vile person, a libertine?” This criticism of the clergy brings to mind Sand’s views about her husband and suggests a connection between the dissolute behavior and abusive authority of husbands and priests. A growing hostility toward male power in both personal and religious matters shows up as well in Sand’s resentment of Aurélien, who believed that while M. Dumont may have converted for solid reasons, Mme Dumont, as a weak-minded woman, could only have followed someone else’s lead. Both men and women, Sand argued, were capable of taking “an action that must have no other motive than that of a deeply personal conviction.” And she insisted as well that “God opens his arms to those in this religion as well as the other, if they have embraced it in order to serve him better.” Sand followed this daring statement by assuring her friend that she had no intention to convert and stating at length what she called “my profession of faith”:

I believe in the Roman Church in which I was raised. I believe in it on all points; I follow all of its rules. I don’t feel myself intelligent enough to discuss it. I never attack it, I never defend it however tempted I might be by those who cleverly ridicule it, however indignant I might be with those who impiously insult it. I haven’t examined it at all, and I don’t want to. What does it matter if some of the ceremonies are useless, as long as they do no harm, as long as the moral foundation is that of Jesus Christ, sublime and divine? If I came to believe that this morality had changed (which it is has not) and that the Protestants followed it more closely, I would regard it as a cowardly weakness to continue to practice a religion only because of those around me. . . . I would ask God to speak to my heart and if I heard the voice of my conscience tell me to change my dogma, I would do it the next day. . . . I see nothing but good and laudable in our Catholic customs. I follow them with an interior satisfaction. I recall with gratitude the sweet and simple instruction I was given at the convent. I love my religion as much as I believe it.36

Sand was still committed to Catholicism, and still committed to her marriage, but by the end of 1825 she no longer accepted the authority of the church or of her husband to define her religious identity and family status. These were now to be determined by her own conscience, and her letter to Zoé Leroy suggests that she could imagine herself crossing a religious border, especially because of the bad behavior of the clergy. Sand’s letters to Casimir and Zoé were written in the midst of a personal emotional crisis, and in them she made no effort to formulate a systematic analysis of marriage and the church. Taken together, they nonetheless illuminate how her growing sense of the need for independence within marriage was intricately related to a commitment to religious liberty.

Sand still considered herself a Catholic, but her belief and behavior grew increasingly unorthodox in the late 1820s. Although she remained on friendly terms with some of the local clergy, Sand’s religious practice became irregular. Late in 1827, apparently to consult doctors about a persistent cough, she traveled to Paris, accompanied by Stéphane Ajasson de Grandsagne. Sténi, as he was known by his friends, had flirted with Sand since they first met in 1820, but during their time in Paris together they become lovers, and not in the platonic mode that she had preached to Aurélien. Although there is no definitive proof, Sand scholars generally agree that Stéphane was the father of Solange, who was born in September 1828.37 Over the next two years Sand continued to put up with an obtuse and at times threatening husband, distracting herself by reading, providing medical care to the peasants of the area, painting and playing music, and visiting friends. These last included Aurélien, with whom Sand at some point may have abandoned her pledge to honor her marriage vows. But Aurélien’s position as advocate general in Bordeaux made him cautious about seeing her in public, and by the spring of 1830 their romance was in its final stages. Although her subsequent life makes it hard to imagine, Sand might have continued to live at Nohant, estranged from her husband but occupied with her intellectual and artistic interests, her children, her estate, and perhaps an occasional lover. But in November 1830, while browsing in Casimir’s office, she found a sealed letter addressed to her, to be opened only after his death. Sand didn’t wait, and what she found was a long and detailed indictment that expressed with brutal candor Casimir’s dislike for his wife.38 Sand confronted Casimir with the letter and announced her intention to move to Paris, supported by an allowance and perhaps income from a writing career she hoped to begin.

Romance and Religion, Love and Despair

In Paris Sand settled into a small apartment on the quai Saint Michel, where she was joined by Jules Sandeau, who was her companion and lover for the next two years. They had first met at La Châtre in July, and Sand was immediately attracted to the aspiring poet, six years younger than herself, who quickly replaced Aurélien in her affections. Over the next several years Sand embraced the bohemian culture in which conventional views about society, politics, and gender were challenged, on the pages in novels, treatises, and poetry, but also in the lives that Sand and many other young people built for themselves in the apartments, publishing offices, theaters, and cafés of Paris. Already accustomed to wearing men’s clothes from her days of riding horses in the countryside, Sand now refined this habit, wearing pants and boots that allowed her access to the streets and the inexpensive standing-room “pits” of Parisian theaters. But throughout her bohemian years Sand continued to be a solicitous mother, spending considerable time in Nohant with her children, arranging for a tutor and then a boarding school for Maurice, and taking Solange with her to Paris in 1832. And she stayed in touch as well with established figures in society, including François Duris-Dufresne, the representative from Nohant to the National Assembly, and Charles Meure, a state prosecutor whom she met when he was stationed at La Châtre in 1826–1827. During her early years in Paris Sand and her friends explored the borderland that separated bohemian from bourgeois culture during the July Monarchy with an intensity that was both exhilarating and exhausting.39

There was little space in bohemian Paris for the Catholic Church. In a letter to one of her circle, the medical student Emile Regnault, Sand suggested that friendship and love had become her new religion. Suffering from fragile health, Sand insisted she would continue to live, because she loved her companions more than God himself: “No, I don’t want to leave you, even though I believe firmly in God, I love you a thousand times more than him, and were he to place my soul in the most beautiful of suns, in the purest of his creations, I would still regret our poor planet, so dirty and ugly, so stupid and cursed, but where I’ve spent such beautiful days, where I’ve tasted such pure affection.”40 In a gesture that symbolized a definitive break from her Catholic past, Sand visited the couvent anglais one last time soon after her arrival in Paris. She found it much changed, with no students because of the unrest in Paris following the July Revolution and the nuns in general somber and anxious. In her autobiography Sand recalls “telling myself I would no longer pass through this gate behind which I was leaving affections preserved at a stage when the gods have no wrath and the stars are not obscured.”41

Sand may have bid farewell to her old friends, including the beloved Sister Alicia, but they were still on her mind, to judge by her first novel, Rose et Blanche, written in collaboration with Jules Sandeau and published in December 1831 under the name J. Sand. Sand later dismissed this work as puerile, but in telling the story of two women, one destined for the convent and the other for a career as an actress, it sketches out the radically divergent paths that she considered before choosing the one that led to bohemia. As would be the case for many of her novels, Rose et Blanche draws heavily on Sand’s own life. Sister Alicia and the abbé de Prémord show up as Sister Adèle and the abbé de P . . . , exemplary religious figures in a Paris convent of English nuns. The archbishop of Auch, a ridiculous and pompous throwback to the Old Regime, is modeled on M. Leblanc de Beaulieu, the bishop who had presided over the death of Sand’s grandmother ten years earlier. The plot of Rose et Blanche is full of improbable twists and turns, as the authors acknowledge in an epilogue, but it conveys nonetheless an equivocal position toward Catholicism. Blanche is attracted to the religious life, but she is a timid creature, suffering from amnesia brought on by a sexual assault. She dies following a marriage to a feckless young man, Horace, who is the man who assaulted her. Horace was in fact in love with Rose but was prevented from marrying her by a snobbish but devout sister. After a short career in the theater Rose ends up deciding on a life in the convent, where she teaches singing to the students and lives in Blanche’s old cell. The novel concludes with an endorsement of the cloistered life: “The air of freedom is no longer needed by those who have travelled the world and known men. Friendship, the leisure to study, the sun, air and flowers, these are the elements of a nun, and does a heart that love and glory have betrayed need anything more?”42 To judge by Sand’s life, this question would be answered with a resounding yes, but this may not have been perfectly clear to her in 1831.

Love and literature dominated Sand’s life during the 1830s, a period of passionate affairs with lovers who included Alfred de Musset and Frédéric Chopin, and of literary successes that established her as one of the leading authors of the time. Her career took off in 1832 with the publication of Indiana, a novel that became an instant bestseller and drew enormous public attention for its criticism of the subservient position of wives.43 Indiana marked a new stage in Sand’s personal identity as well; it was the first work published under her nom de plume, which she subsequently adopted in conversation and correspondence. The story she told of the deeply unhappy marriage between Indiana and a retired army officer, Colonel Delmare, drew heavily on Sand’s own life. Alienated from her husband, whose behavior clearly recalls that of Casimir, Indiana falls in love with the handsome but coldhearted aristocrat Raymon de Ramière before finally finding happiness with Ralph Brown, a stolid Englishman who loves her sincerely. Sand’s main targets in Indiana are patriarchal authority and loveless marriage, though the character of Raymon also allows her to criticize men who use a sentimental vocabulary to hide their heartless seductive intentions. Religious feeling is not a central concern, but it shows up nonetheless as a crucial element in pushing the story forward, and in its final resolution. Despite her passion for Raymon, Indiana attributes her ability to resist his advances to God’s help, and her belief in God also helps keep her from choosing suicide as a way to end her misery.44 Toward the end of the novel, when Raymon tries to lure her back to France from the Ile de Bourbon, Indiana declares at length her religious convictions, which she contrasts with his self-serving religiosity:

As for me, I have more faith than you have. I serve the same God but I serve him better and with a purer heart. Yours is the god of men, the king, the founder, and protector of your race; mine is the God of the universe, the creator, the support, the hope of all creatures. Yours has made everything for you alone; mine made all species for each other. You think yourselves masters of the world; I think you are only its tyrants. . . . But the feeling of the existence of God has never reached your heart; perhaps you’ve never prayed to Him. I have only one belief, probably the only one you don’t have; I believe in Him. But the religion you have invented, I reject. All your morality, all your principles, are but the interests of your society that you have erected into laws and that you claim emanate from God Himself, just as your priests have set up the rites of church worship to establish their power and wealth over the nations. But all that is lies and blasphemy. I who invoke God, I who understand Him, I know very well that there is nothing in common between Him and you and that it is by clinging to Him with all my strength that I can detach myself from you who continually strive to overturn His works and sully His gifts.45

Sand’s religious convictions in 1832, to judge by this text, already included the social dimension that would take on even greater weight over the next several years. But Sand’s extended reflection suggests even more an intensely individualized religiosity, intimately connected to a sense of independence from male authority and institutional religion.

Working at a furious pace, Sand published Valentine, her second novel, in November 1832, another work in which the inequities of contemporary marriage take center stage.46 In this case, the union of the aristocrat Évariste de Lansac with the naïve but well-intentioned Valentine is condemned as a loveless affair arranged only for the sake of family status and a venal aristocracy. Valentine’s true love, Benedict, is a well-educated and artistically gifted peasant but out of reach because of the social conventions that prohibit such a mésalliance. As in Indiana, religious scruples prevent Valentine from consummating her affair with Benedict, which remains platonic despite their mutually acknowledged love. And as in Indiana, fear of God helps them to ward off the idea of suicide as the solution to their impossible situation. Sand’s heroines were certainly more scrupulous than she was with regard to marriage vows; the strained but virtuous fidelity of Indiana and Valentine might have been a prudent gesture toward an audience unwilling to condone the unbridled passions of bohemian Paris. But Sand’s next novel, Lélia, along with her letters and journals from 1833 to 1835, reveal that she shared the despair expressed by Indiana and Valentine as they struggled to reconcile their physical desires and spiritual aspirations.

Sand’s successes with Indiana and Valentine were not at all matched by Sandeau, whose youthful indolence increasingly wore on her and led eventually to the end of their affair early in 1833. The arguments and resentment that accompanied this breakup took place in a somber political context, with Sand observing from her Paris apartment the ravages of the cholera epidemic that began in March 1832 and the brutal repression of the republican uprising of June.47 It was during this period of personal and public hardship that Sand wrote and published Lélia, which marked a sharp departure from her previous novels in its extended engagement with philosophical and religious questions. These reflections accompanied the story of the doomed love between Lélia and Sténio.48 Sténio is a young poet, madly in love with Lélia, whose unhappy past includes a failed affair that makes it impossible for her to respond physically to his advances. Three other characters play central roles in the novel: Trenmor, a friend of Lélia, an ex-prisoner whose incarceration brought him to a stoic resignation to the will of God; Magnus, a guilt-ridden Catholic priest obsessed with Lélia; and Pulchérie, Lélia’s sister, a courtesan who has unashamedly devoted herself to a life of sensuality. These characters do not appear as individuals set within a carefully observed context, as in Sand’s earlier novels, or those of Balzac and Stendahl. They represent different perspectives on life, choices to be made about the relationship between body and soul, God and man, good and evil. In a note written by her friend Gustave Planche during a discussion of the novel as it was being drafted, the characters are identified with predominant traits: Lélia/doubt, Trenmor/stoicism, Sténio/credulity, Magnus/superstition, Pulchérie/sensuality. In her own notes on the novel Sand identifies with all of these characters: “Some will say that I’m Lélia, but others would be able to recall that I used to be Sténio. I’ve also had days of uneasy devotion, of passionate desire, of violent combats and fearful austerity, where I’ve been like Magnus. I can be Trenmor as well. Magnus, it’s my childhood, Sténio, my youth, Lélia is my maturity; Trenmor will be my old age perhaps. All these types have been in me.”49 In her autobiography, Sand recalls not being able to speak to her friends about the “preoccupations” that drove her to write Lélia: “To become an atheist and suppose an unintelligent law ruling the fortunes of the universe is to admit something far more extraordinary and unbelievable than to avow oneself of limited reason surpassed by the motives of infinite reason. Faith thus triumphs over its own doubts, but the wounded soul feels the limits of its power shrink narrowly back on itself, and secure its devotion in such a little space that pride forever flees and sorrow remains.”50

Sand’s comments suggest how her characters offered her a range of religious options, but she oversimplifies them as well, for in the course of the novel the positions of Lélia, Sténio, and the others are far from stable. They debate, criticize, and waver in their judgments, agonizing over the choices that confront them. At times they seek to reassure each other that a merciful God exists, revealed in nature, who offers hope for eternal peace. At other times they admit to searing doubt, as when Magnus, called to administer to Lélia when she appears to be dying, cries out, “Oh, God. . . . Oh, sweet dream which has fled from me! Where are you? How will I find you again? Hope, why have you abandoned me? . . . Madame, allow me to leave you. When I am with you all my doubts take over. Here in the presence of death my last hope and my last illusion vanish. You want me to help you find God and give you heaven. You are going where you will find out if He does exist. You are happier than I because I don’t know.”51 On several occasions in the novel Lélia makes the same point, describing herself as torn between belief and doubt. When Trenmor asks her if she believes in God she answers equivocally: “Nearly always!”52 To Sténio she confesses that “I need heaven, alas, but I doubt it exists.”53 At other times she preaches to the young poet a religion in which God grants moments of mystical ecstasy, anticipations of a final harmony in which the soul will be freed from the “burning, insatiable desires” of the body: “We continue to be deceived until disillusioned, enlightened, purified, we finally abandon hope of a durable affection on earth. Then we raise to God that enthusiastic, pure homage that we should have directed only to Him.”54 The conclusion, in which Sténio commits suicide and Lélia is strangled by a crazed Magnus, undermines any facile and redemptive interpretation of the novel. Reviewers at the time judged it as a dark comment on French culture, an indictment of what Sainte-Beuve called “the powerlessness to love and believe.”55 Sand herself described the novel in 1834 as “a cry of pain, a bad dream.”56 As with her previous novels, Lélia confronts the troubled relationships between men and women, the tension between sexual desire and love, but these were now cast in a larger religious framework that was only a marginal presence in Indiana and Valentine. From my perspective, Lélia is a novel that illuminates the pain and despair that could accompany religious liberty as experienced by individuals intensely aware of their subjectivity, troubled and indecisive about God, his existence, his nature, and his relationship to humankind.

The religious crisis Sand expressed in Lélia was in no sense relieved by its publication and continued to trouble her over the next two years. For Sand, as with Lélia, religious anxiety was inseparable from a turbulent love life, as she pursued an ideal human lover and a reassuring God, both of whom seemed hopelessly out of reach. The publication of Lélia and the breakup with Sandeau were followed by a very brief encounter with Prosper Mérimée and a relationship with the actress Marie Dorval that may or may not have been sexual. But the most melodramatic period of Sand’s life began in June 1833, when she met the young Alfred de Musset. Sand was drawn to Musset for his artistic brilliance, as a leading poet of the romantic generation, a writer whose tortured characters recalled those in her own work.57 Sand’s maternal instincts may also have played a role, as she hoped to save Musset, only twenty-two years old at the time, from a life of debauchery that threatened his health and his art. Over the next year these two carried on a tempestuous affair, with the central act a famous winter voyage to Venice, where both fell ill and Sand began an affair with Pietro Pagello, the Italian physician who cared for them both. After recovering from an illness that at times produced hallucinatory fits of rage, Musset returned to Paris while Sand stayed in Venice with Pagello, writing furiously to cover debts that she could never quite manage to pay off. She and Pagello came back to France together in August 1834, but even the exceptional good nature and patience of the Italian doctor could not endure the renewal of the destructive relationship between Sand and Musset that occurred in a continuing series of stops and starts over the next several months. Pagello returned to Italy in October 1834, leaving the two miserable lovers battling, separating, and reconciling until they definitively broke in March 1835.58

The pain and despair that Sand experienced in her tortured relationship with Musset have been described repeatedly, based on the surviving correspondence and notebooks that provide intimate testimony of an emotional crisis. But Sand’s writings from this period show that her affair was also the occasion for her continuing pursuit of the religious questions that she had dealt with imaginatively in Lélia. Writing from Venice in May 1834, Sand referred to Musset’s mocking attitude about her religiosity but then went on to compare God’s love with his, a comparison not to the advantage of her earthly lover: “And God Himself, what you call my chimera, what I call my eternity, isn’t it a love that I embraced in your arms with more passion than in any other moment of my life? I find there, close to me, my friend, my support. He doesn’t suffer, he isn’t weak, he isn’t suspicious, he doesn’t know the bitterness that eats away the heart, he doesn’t need my strength, he is calm, he loves me and leaves me at peace, he is happy without making me suffer, without making me work for his happiness. And as for me, I need to suffer for someone, I need to use this excess of energy and sensibility I find in myself. . . . Oh why could I not live with you both, and make you both happy without belonging to either one or the other.”59 In this passage, which might easily have been introduced into Lélia, Sand reveals her longing for both human and divine love, which at times seemed to come together in Musset’s arms. But God’s love, described in terms that echo Paul’s famous description in his First letter to the Corinthians (13:4–8), has nothing of the bitterness and jealousy that soured her relationship with Musset. As different as they are, however, God, like Musset, seems to want to possess Sand, while she aspires to love both without surrendering to either.60

Sand’s religious despair led her at times back toward the Catholic Church, seeking the kind of certainty and comfort she had found for a time in the couvent anglais. In a note written in March 1833, just before her first meeting with Musset, Sand recalled with nostalgia the comforts available to those who can confess their sins to a priest and be forgiven and consoled. But such relief seemed unavailable to people like herself, “without enthusiasm and without poetry, who fade away slowly in the shade of our intimate suffering and belated repentance, what can we do with this fiery coal that devours our conscience? Where can we find relief when the stones of the churches and the lustrous water of the sanctuary no longer refresh us?”61 This hope for forgiveness in the confessional recurs in the journal intime that Sand began keeping in November 1834, as her affair with Musset was dissolving in a series of bitter fights full of recrimination and resentment. In the journal Sand addresses Musset, accusing him of demeaning her in public, of humiliating her, despite her continued passion for him. But she also appeals directly to God, praying for forgiveness and expressing grief about the flawed human nature that he has created, and that explains her own failings. In her despair Sand describes an evening visit to the church of Saint-Sulpice, where she cried out, “Will you abandon me? Will you punish me to this point? Isn’t there anything I can do to earn your forgiveness?” At this point Sand writes that she heard a voice respond, “Confess, confess and die.” Remarkably, Sand did go to confession the following day, “but it was too late, and I wasn’t able to die, one lives, one suffers all this, one drinks his chalice drop by drop, one feeds oneself on bile and tears, one spends every night sleepless, and in the mornings one nods off with frightening dreams.”62 During Sand’s bohemian years she broke from orthodox Catholicism, but her novels, letters, and journals show her still constrained by a God she in turn loved, respected, feared, and resented, sentiments that also defined her relationship with her earthly partners, and especially Musset.

Musset did not share Sand’s religious beliefs, but in Confessions of a Child of the Century he sets a fictionalized version of their affair within a general context of religious doubt. Sand herself admired his book for its honest treatment of their life together and its insight into the cultural moment in which they carried out their affair. In describing the mood of young people, such as Sand and himself in 1834, Musset draws a contrast between “exalted spirits, sufferers, . . . expansive souls who yearned toward the infinite, bowed their heads, and wept” and materialists who insisted that “man is here below to satisfy his senses. . . . To eat, to drink, and to sleep, this is life.”63 In the end Sand failed to keep Musset from the life of drinking and debauchery that eventually killed him, but both of them understood that Sand’s love for him was tied to a sense of spiritual yearning that even a religious skeptic like him could appreciate.

Sand’s life was clearly exceptional, but it was also fascinating to the French public of the 1830s, which had an insatiable demand for her writings. Marriage and the fraught relationships between men and women were at the heart of Sand’s concerns in this period, and were clearly on the minds of her readers as well. In her treatment of families, sexuality, and love Sand expressed the doubts and struggles of individuals, especially women, who sought a greater freedom of choice in these matters. Sand’s own life, as well as her writings, testifies to the painful complications that accompanied such choices. Her life and writings show as well that choices about love, sex, and marriage were inseparable from questions about God, religion, and the Catholic Church. In 1835 Sand was in the midst of a personal and religious crisis that left her in a state of doubt and despair, but also free to choose a path that would eventually lead her to embrace a religion of humanitarianism.

A Final Conversion: Republicanism, Social Justice, and the Religion of Humanity

Sand’s personal life did not become simpler with the end of her affair with Musset, to say the least. In April 1835 she met Louis-Chyrsostome Michel, known as Michel de Bourges, a prominent lawyer and a staunch republican. Initially drawn by his charismatic defense of radical reform, within weeks she had become his mistress, a relationship that only further complicated her marriage with Casimir. After apparently agreeing to leave Nohant in exchange for the income from a property in Paris, Casimir grew increasingly resentful about his wife’s affairs, and her dominant status at the estate. He finally exploded in a drunken tirade at the conclusion of dinner on October 19, when several guests had to forcibly prevent him from hitting his wife, or perhaps even shooting her.64 Sand immediately began legal proceedings for a separation, starting a court case that dragged on for years before she finally won control over Nohant and custody of her children. Public life was equally somber in this period, marked first of all by the brutal repression of uprisings by republicans and workers in Lyon and Paris in April 1834. In its aftermath the government passed laws restricting the rights of association and the press and began a trial of 121 conspirators charged with organizing the rebellion.65

Early in 1835 Sand continued to express in both her published work and private letters a religious anguish that corresponded with the miserable state of her affair with Musset. In her fifth lettre d’un voyageur, published in the Revue des Deux Mondes in January, Sand mourned that “God is no longer in me” and that “many have, like me, fallen into the abyss. It is a vast world, it is like a world of the dead moving and stirring beneath the world of the living.”66 Writing to her confidant Sainte-Beuve in April she reflected nostalgically on her former Catholicism, and sadly on her current confusion: “But what can one do to enter this temple [the Christian religion]? Every time I pass before its door, I genuflect before this divine poetry, seen from afar. But if I approach, I no longer see what I believed could only be found there. It is no more than a surface for what I was looking for. I would like to find my God in all his majesty and glory and prostrate myself before him, and have no one of my species tell me, it is He, because then I would doubt it. . . . What crime have I committed to be condemned to the role of wandering Jew?”67 Sand, like Edgar Quinet and others in this period, found in the “wandering Jew” a symbol that linked an aspiration to believe with an acceptance of doubt. Just one month later Sand again described herself, in a letter to her Saint-Simonian friend, Adolphe Guéroult, as a religious skeptic committed to finding her own way to God. While encouraging him to travel to Egypt, where he would meet up with the exiled leaders of the group, Sand also cautioned him against putting his faith in any individual, a “fanaticism” that she found “degrading and stupid.” Speaking for herself, she declared that “I have not enrolled under the banner of any leader and while maintaining esteem, respect and admiration for all those who nobly profess a religion, I remain convinced that there is not under the heavens a man who deserves to be approached on bended knee.” In this same letter, however, Sand admitted that she had just recently fought off precisely such an attachment, “refusing to modify in the least my skepticism,” despite having met “a very great man of politics.”68

The politician in question was Michel de Bourges, the first of three men who would play a decisive role in Sand’s final conversion in the latter half of the 1830s. Despite her reservations about following the religious lead of others, Sand became for a time a devoted follower of all three, but more or less quickly she also found reasons to criticize them, a process that led in the end to her own particular religious position. Sand’s amalgamation of ideas drawn from her past experience and from the religious resources of the 1830s does not constitute a major contribution to the history of theology. But these ideas do provide a fascinating example of the religious choices the leading woman writer of her generation pursued in the 1830s, which she shared with an enormous and fascinated public.

The crisis of religious doubt that plagued Sand through her writing of Lélia and her affair with Musset began to dissipate soon after she met Michel de Bourges during a trip to Bourges on April 9. Responding to her new friend in a rhapsodic letter to Franz Liszt, Sand asked him to “rejoice, if you have any affection for me; I feel myself reborn and I see a new destiny open itself before me. I can’t quite say yet what it is, but it is no longer the slavery of love. It is something like a faith to which I will consecrate everything that is in me, the God who has not yet descended on me, but for whom I’m now building a temple, that is to say, purifying my heart and my life.”69 In her autobiography Sand recalls the weeks after her meeting with Michel as the moment of “a swift conversion,” and she refers to his letters from this period as a form of “proselytism.”70 The gospel of republicanism that Michel was preaching was not entirely new to Sand. Prior to meeting him she had identified broadly with principles of the July Revolution of 1830, understood as offering hope for “a more generous constitution, more profitable for the lowest classes of society, less exploitable by the ambitious.” But she acknowledged as well that she had not thought seriously about politics and had no great hopes for the future, a posture of “social atheism” that Michel found egotistical.71 From their first meeting at Bourges, when they spent the whole night in a conversation that included her friends Alphonse Fleury and Gabriel Planet, Michel challenged Sand to “extend this ardent and dedicated love, which will never receive its recompense in this world, to all humanity which is disparaged and in pain. Lavish not so much care on one creature! Alone, none of them merits it, but together they deserve it in the name of the eternal author of creation!”72 In her sixth lettre d’un voyageur, addressed to Michel and published in the Revue des Deux Mondes soon after their first meeting, Sand publicly declared herself a newly enlisted soldier in the cause of radical republicanism, a vow that she immediately began to fulfill by throwing herself into the most controversial political trial of the 1830s. Michel had taken a leadership role in the defense of 121 men accused of plotting and carrying out the republican rebellions that broke out in Lyon and Paris in April 1834. In May Sand traveled to Paris, where at Michel’s request she drafted a letter to be signed by all the defense lawyers, stating their principles.73 It was during their time in Paris that Sand and Michel also became lovers, the start of another affair that would end in jealousy, resentment, and mutual recriminations.

Sand had a long list of reasons for breaking with Michel, and even in her earliest enthusiasm for him she expressed serious reservations about his personality and his politics. Sand opened the same public letter of June 1835 in which she accepted his political teaching by referring to him as a “high-minded hypocrite” and chiding him for thinking “that it is a sense of duty and not your instinct for power that leads you up the steep and fatal ascent.”74 She was suspicious at the outset as well of Michel’s stated willingness to endorse violence as the means to his end, though she did not take seriously his comment to her that “if it were my duty to kill you, I would tear you from my heart and strangle you with my own hands.”75 Sand’s letters to Michel in 1836 and 1837 show her at times pleading for his love but also complaining of his jealousy, arrogance, and authoritarianism. “Submissiveness and servile fear, that’s all you want,” she wrote in January 1837.76 Even in the midst of a temporary reconciliation in March 1837 Sand expressed bitterness about Michel’s patronizing attitude toward women: “You treated me like a child whose sufferings one appeases with some potion. You have never seen women except as children; you believed that one amuses them until the day when one no longer cares for them, and then they pass on to other loves or to the cult of some social vanity.”77 By the summer of 1837 Sand was finished with Michel as a lover and mentor. She remained grateful to him for his help with her legal troubles with her husband, and in her autobiography from the 1850s she continued to praise his courageous defense of his ideals in the 1830s. Through Michel, Sand was drawn into the “social question,” and for the rest of her life she favored policies that she believed would address the issues of poverty and inequality. But she recalled herself in this period as “searching for a single religious and social truth,” a quest that the worldly lawyer could not fully satisfy.78 In the end she came to understand these problems not within the Jacobin-like framework of Michel but from the perspective of two religious prophets, Lamennais and Leroux.

Even before they met Sand was drawn to Lamennais, first of all through her reading of The Words of a Believer, which she described briefly in her third lettre d’un voyageur, of September 1834. Responding to the criticism of an Armenian monk with whom she was chatting on the island of San Servolo near Venice, Sand wrote that “while reading it I felt a livelier faith dawn in me; the love of God, the hope of seeing his kingdom come on earth had transported me to the foot of the eternal throne. Never had I prayed so fervently.”79 Sand finally met Lamennais during his stay in Paris in the spring of 1835, where he along with Michel served as members of the team organized to defend the workers in the “monster trial.” To the fervent atmosphere fueled by intense discussions of political tactics and republican dreams, and inspired by the virtuoso piano performances of Liszt, Lamennais added a compelling religious dimension, casting the work of Sand and her friends as part of a providential moment in which monarchies would give way to popular democracies.

For a few months in 1835–1836 Sand was swept away by Lamennais, who appeared to her as a savior, someone in whom she could believe even in her darkest moments. “In the days of my most bitter skepticism,” she wrote to him, “you were always the only divine emanation, clothed in flesh, that my doubts respected, the spirit of negation lodged in me did not dare to attack you. For years I’ve regarded you as the only child of man who could do something for me, and whose virtue seemed to me stronger than my pain.” At the conclusion of this letter, full of inflated rhetoric, Sand asked Lamennais to become her spiritual director: “Guide me, no longer let me write for the despairing unbeliever, and allow me to submit to your authority any serious writing produced in my solitude.”80 Lamennais responded to this remarkable request to submit all her work to his judgment with a grandiloquent letter that in turn flattered Sand and called on her to fulfill a divine mission: “I well knew, Madame, that a soul as strong and elevated as yours would sooner or later take flight towards other regions than those where the present generation wanders so painfully.” Like Michel de Bourges, Lamennais insisted that Sand expand her understanding of love so that it would embrace all of humanity, a sentiment that would necessarily include the love of God as well: “Life, it is love, but the love of others, of God first of all, of our brothers next, and this life must expand and overflow, and rise like an ocean that never ebbs.”81

In a period just after he had been condemned by the pope and abandoned by most of his Catholic friends, Lamennais eagerly took up Sand’s offer of friendship and accepted the role of spiritual adviser. His old friends were scandalized by an association with “this shameless George Sand . . . who has written novels so abominable that no honest women would confess to having read them.”82 From Sand’s perspective, Lamennais was destined to play the role of the abbé de Prémord, as she wrote a friend from her convent years, Sister Eliza Anster: “I have finally succeeded in placing in another holy priest the great personal esteem and unlimited confidence in his intelligence that I had for [the abbé de Prémord].”83

Sand was infatuated with Lamennais for a time, seeing in him a later version of the Jesuit who advised her during her convent school years. But their friendship cooled when he tried to impose on her his views on women and marriage. In 1837 Sand agreed to contribute several articles to Le Monde, a paper that Lamennais agreed to edit after leaving once and for all his home in Brittany. Objecting to her views on the equality between men and women, he took the liberty of cutting some passages he believed offensive without consulting her. Sand’s response, while it began with a show of respect, insisted on divorce as the solution to the injustices within marriage, a position in which she explicitly reversed their roles: “Believe me, I know better than you, and for this one time the disciple dares to say: ‘Master, there are paths you have not walked, abysses where my eyes have plunged, while yours were fixed on the heavens. You have lived with angels; me with men and women, I know how one suffers, how one sins, how one needs a rule that makes virtue possible.”84 Sand never broke completely with Lamennais; she continued to acknowledge his crucial role in her political and spiritual conversion of 1835–1836 and mourned his death in 1854.85 At the same time that she was moving away from Lamennais Sand was forming an attachment to Pierre Leroux, another of the prophets from the 1830s who combined religious fervor with social radicalism. Leroux influenced Sand for a longer period and with greater impact than did Lamennais, but he was the last man to play the role of spiritual guide for her, ending a series that began with François Deschartes and the abbé de Prémord.