2

VIRTUE, LOVED AND LOST

CONSTELLATIONS

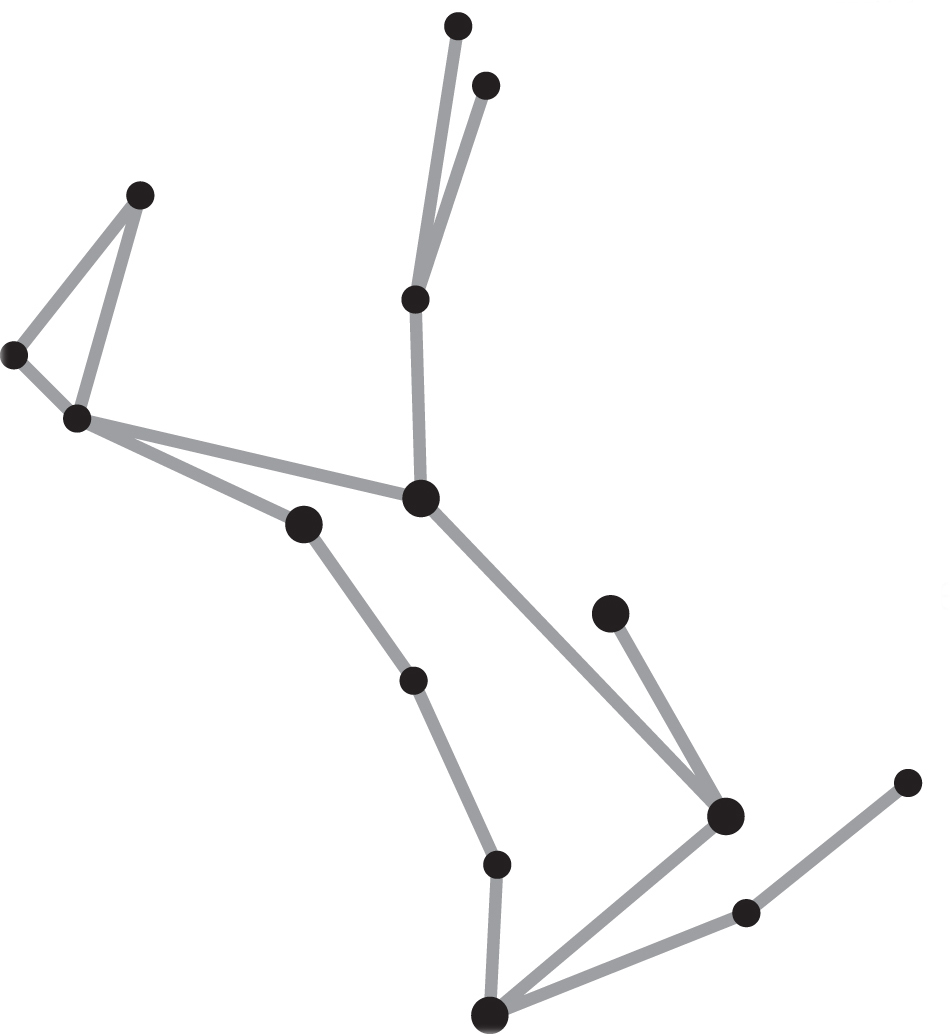

SOUTHERN WREATH (Corona Australis)

STARS

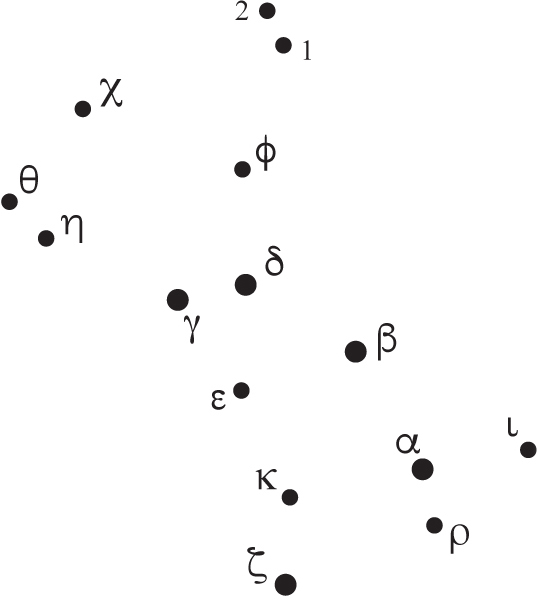

EAR OF GRAIN (Spica)

HERALD OF THE VINTAGE (Vindemiatrix)

Zeus, the god of sky and storm, wielded the awesome power of lightning and thunder. Into battle he bore his jagged bolts and hurtled them with fury at his foes. With this weapon, he led the Olympian deities and faithful mortals to vanquish the Titan host. Now Zeus ruled unrivaled over earth and sky.

The victory of the gods brought happiness and harmony to the human race. People dwelled in peaceful repose with neighbors and with nature. They cherished the flora and fauna that flourished around them. They remained respectful—fair and just—in close accord with all creation. In return, they found their needs for food and shelter fully met.

They thrived according to the words of Hesiod, the poet and prophet, who said, “Those who do not turn aside from justice at all; their city blooms and the people in it flower. For them, Peace, the nurse of the young, is on the earth, and far-seeing Zeus never marks out painful war; nor does famine attend straight-judging men. . . . For these, the earth bears the means of life in abundance.”1

ASTRAEA, THE STARRY GODDESS

During this golden era, Astraea—the starry goddess of purity, peace, and benevolence—lived her immortal life among the childlike mortals she loved.2 From ancient lineage she descended, as the luminous daughter of Astraeus and Eos, the god of Dusk and the goddess of Dawn.

Astraeus and Eos also brought forth other “shining stars with which the sky is crowned.” Among them is Phosphoros—the morning star—who rises radiant above the eastern horizon, heralding the approach of her mother, Dawn. Their other children include the buffeting breezes: Boreas, the north wind; Notos, the south wind; Zephyros, the west wind; and Euros, the east wind.3 Unlike their serene and stately sisters, the blustering brothers roam, ever restless—rushing about, pushing against one another to dominate the direction of the wind. Rarely do they rest for long in quiet and calm.

But Astraea’s manner is always soft and sweet—the pleasant personification of peace. In the golden era, she found the simple innocence of humans charming and endearing. She often was seen among village elders, “ever urging on them judgments kinder to the people.” And peace prevailed, “for not yet in that age had men knowledge of hateful strife, or carping contention, or din of battle, but a simple life they lived. . . . The oxen and the plow . . . abundantly supplied their every need.”4

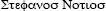

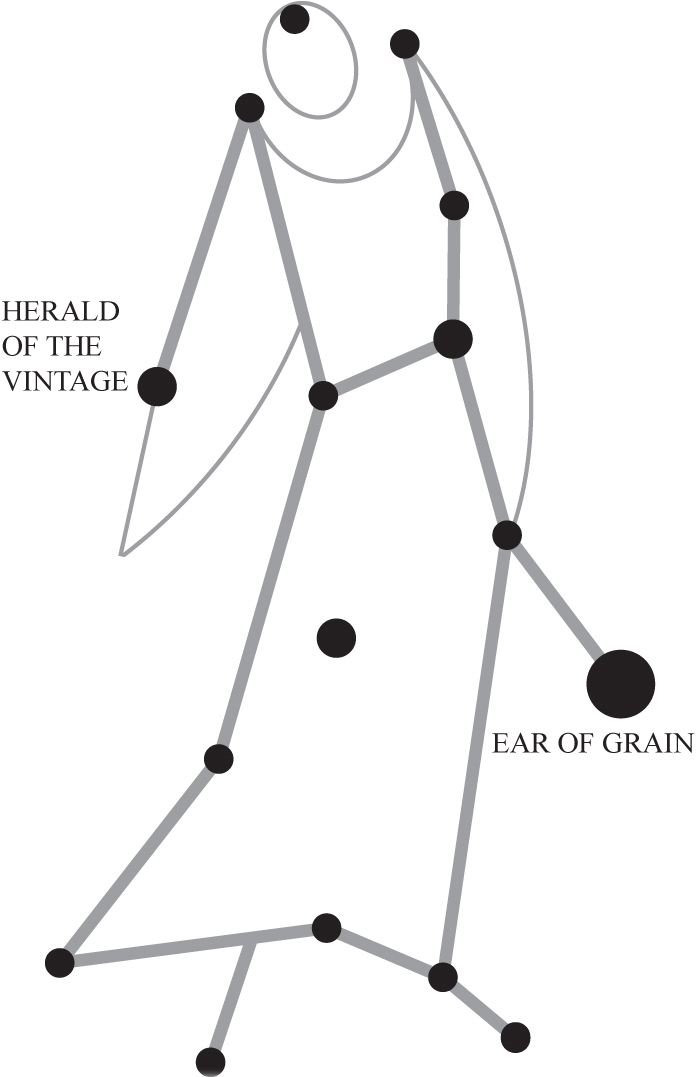

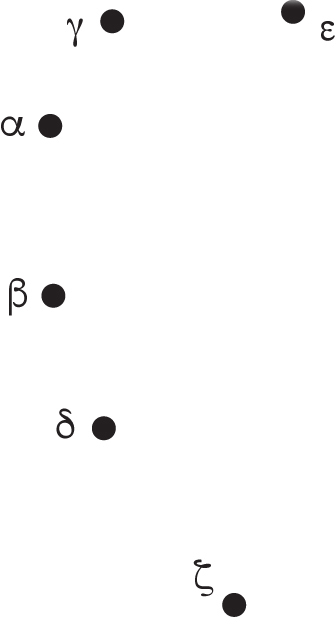

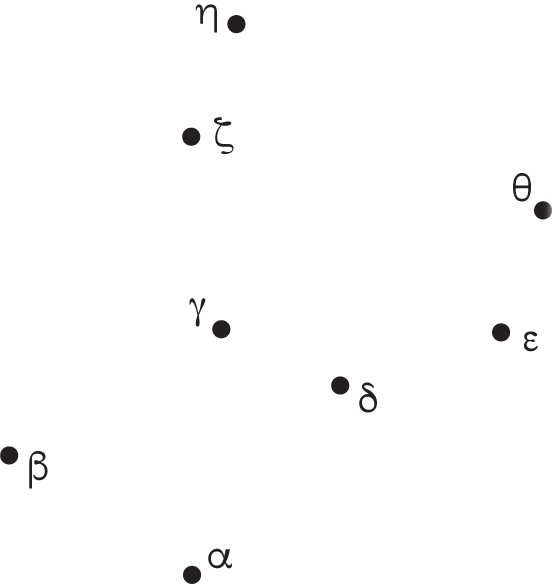

As a heavenly constellation, Astraea appears as a MAIDEN in virtuous youth. Beautiful and benevolent, she carries a bright star named EAR OF GRAIN in her left hand as an emblem of agrarian bounty. On her right wing rests a beam of light called HERALD OF THE VINTAGE. This is the star that annually rises on the eastern horizon at dawn as a sign for farmers to hasten to the vineyards and harvest the ripening grapes.5 In her right hand she raises a palm leaf as a symbol of peace on Earth. Adorned with these—the greatest of earthly gifts—Astraea, the Maiden, shines above as the everlasting celestial sign of divine love for humankind.

Maiden |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Virgo |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Spica |

13h 25m 12s |

−11° 09′ 41″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

In those golden days, other gods and goddesses also granted blessings to earthly beings. Even the centaurs—those galloping, gamboling creatures, half-man and half-horse—received divine gifts from immortal gods. Much like mankind, centaurs range in character from worthless to worthy. But two among them are always held in highest esteem—as high as any human.

THE CENTAUR OF THE MUSES

One of these centaurs is Crotos, the son of Eupheme. Eupheme, a gentle, mild-mannered centaur, served as nanny to the nine maiden Muses—the daughters of Zeus—who reside on the heights of Mount Helicon. On the day that Eupheme gave birth to Crotos, in a shady meadow by a mountain spring, the nine divine sisters helped with the delivery.

The girls giggled in mirthful delight as the tiny centaur, newly born, rose to his feet and wobbled forth on four spindly legs. In time, he found his balance and began to buck and play.

The sisters fell fast in love with the little fellow right away. Adopting him as a brother, they doted on Crotos from that day forward. Through the years, the young centaur benefitted from the blessings of their constant encouragement and kind instruction. Unlike most centaurs, he enjoyed a civilized, cultivated life in their care.

Crotos soon advanced in childhood skills. He reveled in racing with woodland friends. He thrilled at clambering atop rocky pinnacles and peaks. He excelled in notching a feathered arrow in the string of his recurved bow, drawing it back, and sending it swiftly in flight to knock acorns or leaves off holm oak trees.

As Crotos grew older, the Muses immersed him in learning. His knowledge of the universe broadened—in time and space—through the study of history and astronomy, as well as other sciences. With the talented Muses as tutors, his love of the arts also flourished. Their divine duty, after all, was to share the arts of poetry, music, dance, and drama, in addition to serving as patron-goddesses of history and astronomy.6

With their inspiration, Crotos bloomed as a brilliant and bold musician. He developed the method of emphatically marking the rhythm of songs and stories with claps of hands and stamps of feet. He also showed how to follow finales with grateful applause, formed by faster clapping of the hands.

For these innovations, the nine divine maidens lavished endless praise. The rhythmic beats brought their epic tales and music to life for listeners; and applause allowed an audience to respond in joyful ovations. Often, when the Muses performed their livelier songs or stories, Crotos could not contain himself but joined with a spirited dance. Taking his olive-branch wreath from his head, he tossed it on the ground. Then, he merrily pawed and pranced around it, and jumped with leaps and bounds.7

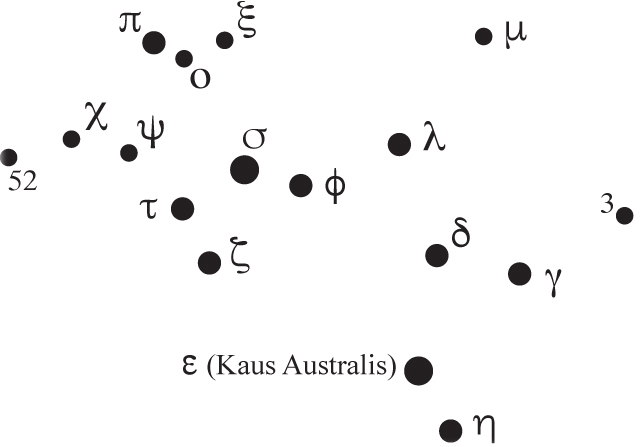

Archer |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Sagittarius |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Kaus Australis |

18h 24m 10s |

–34° 23′ 05″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

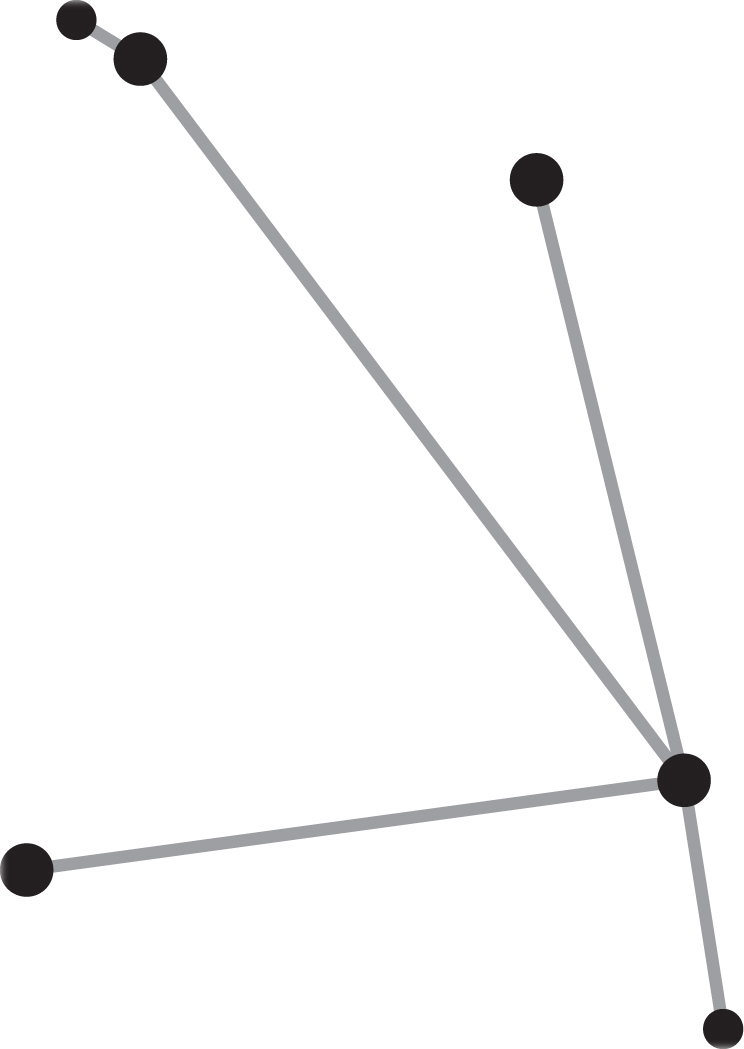

Southern Wreath |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Corona Australis |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

α Coronae Australis |

19h 09m 28s |

–37° 54′ 16″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

The Muses and the two centaurs—mother and son—lived joyful lives together and became like family. At the same time, Crotos’ pious devotion to the nine divine sisters and their father—Zeus—grew stronger through the years. But, alas, each passing year also saw the centaurs growing old and gray. At last, the immortal Muses—forever young—had to watch with heavy hearts as Eupheme and Crotos fell into feeble age and passed away.

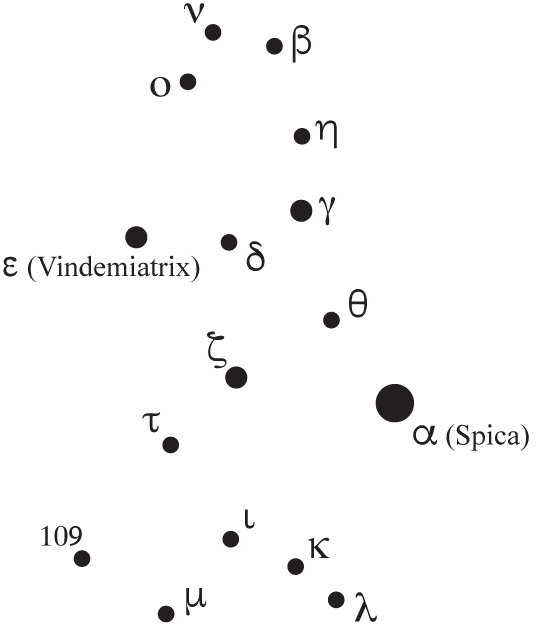

When Crotos breathed his last, the grieving girls asked Zeus to make a place for him—their fondest friend—in heaven. And so, among the stars, he continues to roam as though rambling through the forest. He carries a recurved bow clutched tight in his left hand and drawn back by the right. His wreath of olive leaves lies on the ground before him. Crotos’ constellation is called the ARCHER and his wreath is the SOUTHERN WREATH, because of its location, low in the sky to the south beside his prancing hooves.

CHIRON, THE WISE

Another centaur—Chiron—achieved the same acclaim for his piety and compassion. Like Crotos, he shared none of the savage traits that characterized so many centaurs. Instead, he remained steadfast in mind and spirit.

Chiron surpassed all others in the knowledge of botany and medicine, and excelled in celestial lore and music. He shared this wealth of wisdom by mentoring several students, who rose as lofty pillars of learning and leadership. One of these students was Jason.

When Jason was only an infant, his wicked uncle—the king of Thessaly—plotted to kill him in his cradle to prevent, one day, his possible bid for the throne. Chiron pitied the innocent child and hid him in his cavern home on the heights of Mount Pelion. There he raised him as a son, imparting his knowledge and lore.

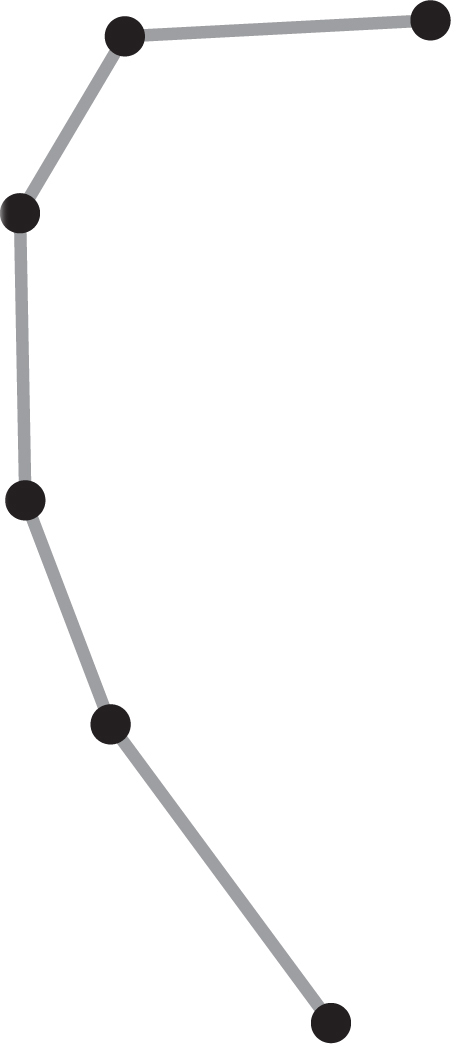

Centaur |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Centaurus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Alpha Centauri |

14h 39m 36s |

–60° 50′ 02″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

By Jason’s side, the child Asclepius—another pupil of Chiron—practiced the healing arts. Asclepius excelled as a promising protégé, and Chiron freely bequeathed to him a command of the curative properties of plants. When it came time to set aside the studies and go outside to play, the boys—Jason and Asclepius—loved to wander the woods together.

Through towering fir trees and shady glades, they climbed to the heights of Mount Pelion. The farther they roamed, the less they feared the deep, dreary forest that surrounded their cavern home. Along the way, they watched for bees that would lead them to wild honey trees. And they learned to recognize useful plants to add to Chiron’s herbarium.

Some years later, when the boys at last left their childhood cave as men, Asclepius chose to journey with Jason and his adventurous band of Argonauts. As a worthy member of the crew, Asclepius served as ship’s physician on the distant voyage to Colchis. At Chiron’s behest, Jason also invited Orpheus, the famed musician, to join the quest.

Chiron, the kindly centaur, supported the Argonauts’ valiant endeavor from start to end. He offered prayers as the men prepared to sail their ship—the Argo—into unfamiliar waters. Then, when the crew loosened the lines and heaved their ship into the surf, Chiron descended to the pebble shore below Mount Pelion. With an impassioned plea to the gods for the safety of his sons—hidden in mumbles beneath his breath—he waved farewell, and, with a smile, wished them a swift return.8 What became of them, we will later learn.

Over the years, rumors of Chiron’s wisdom spread far and wide, and many men sought his sage advice. Often they searched the forested slopes to find the shady pathway to his cave. Heracles (Hercules)—the son of Zeus—knew the trail quite well and frequently came to request the centaur’s counsel.

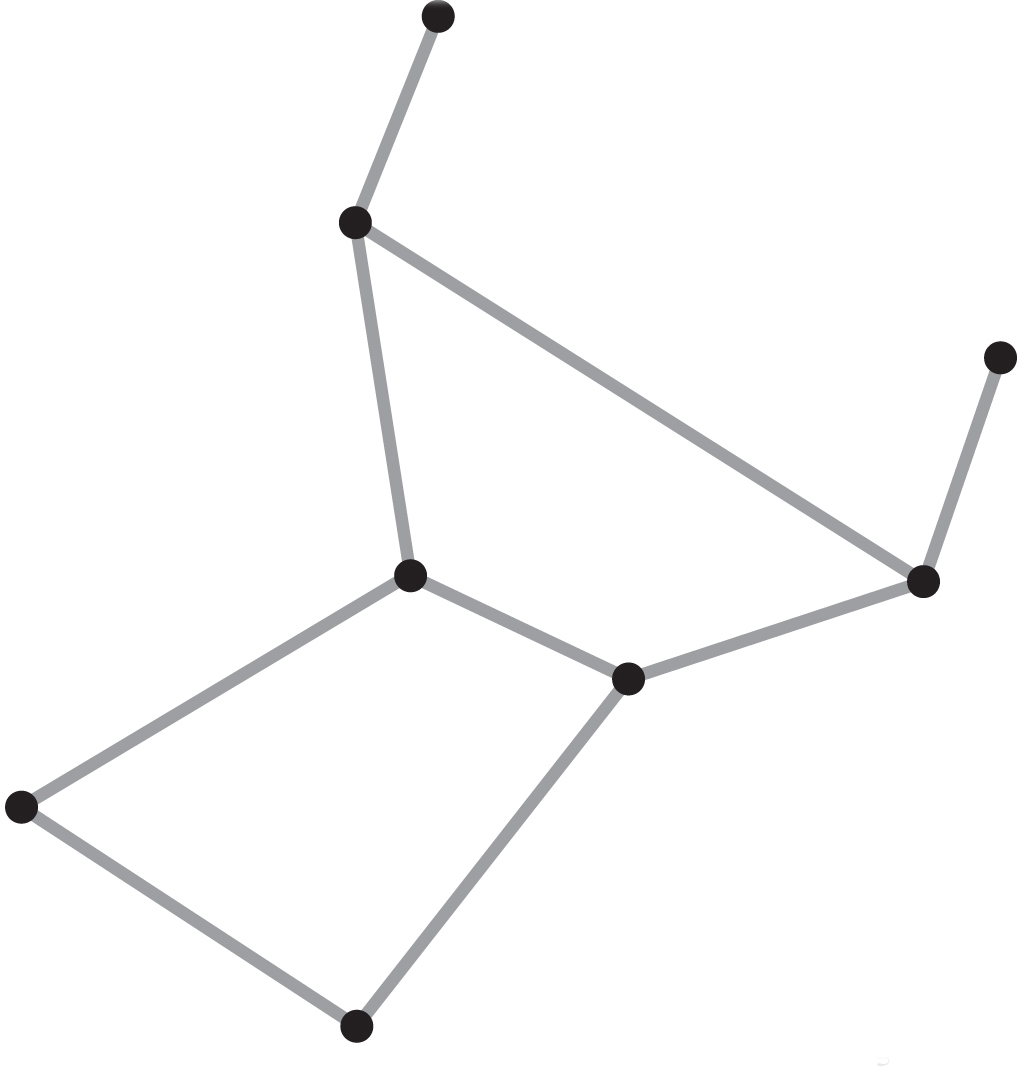

Wild Animal |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Lupus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

α Lupi |

14h 41m 56s |

–47° 23′ 18″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Once, as the two enjoyed a lively conversation in Chiron’s cave, a poisoned arrow—tipped with the venomous blood of Hydra—suddenly slipped from Heracles’ quiver and punctured Chiron’s lower leg. Chiron collapsed and fell into a coma. In horror, the mighty hero, suddenly helpless, held his centaur friend and watched as he closed his eyes and slipped away.

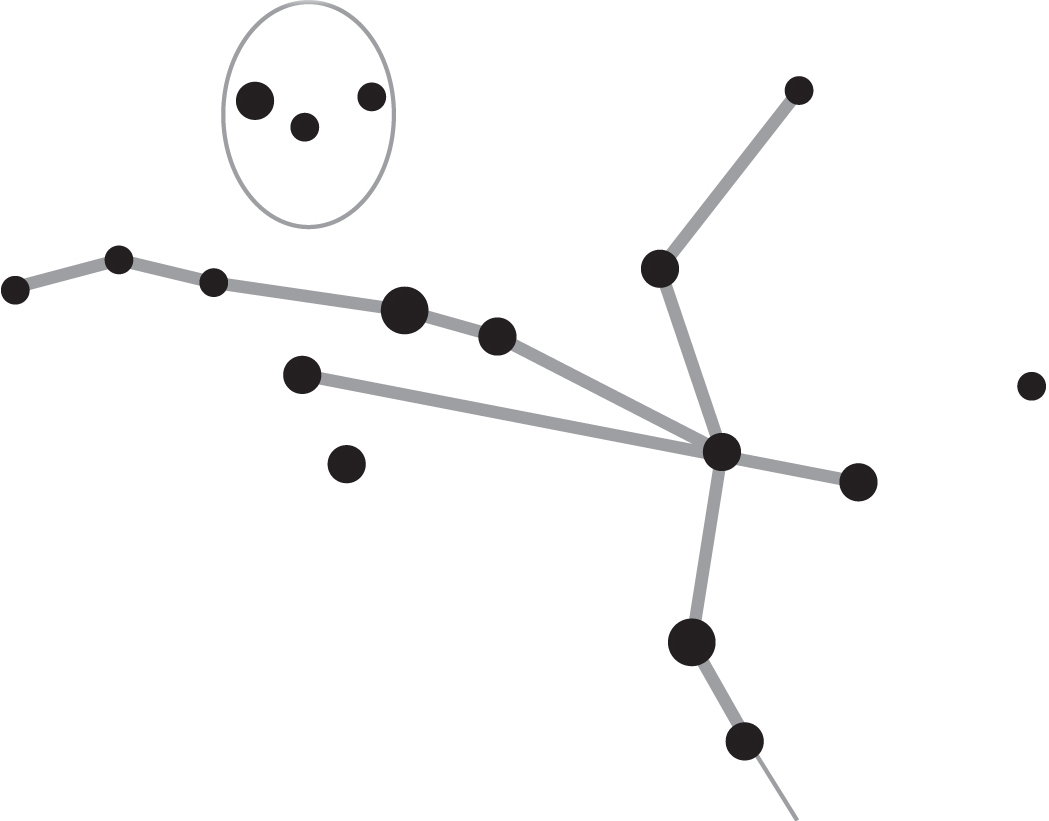

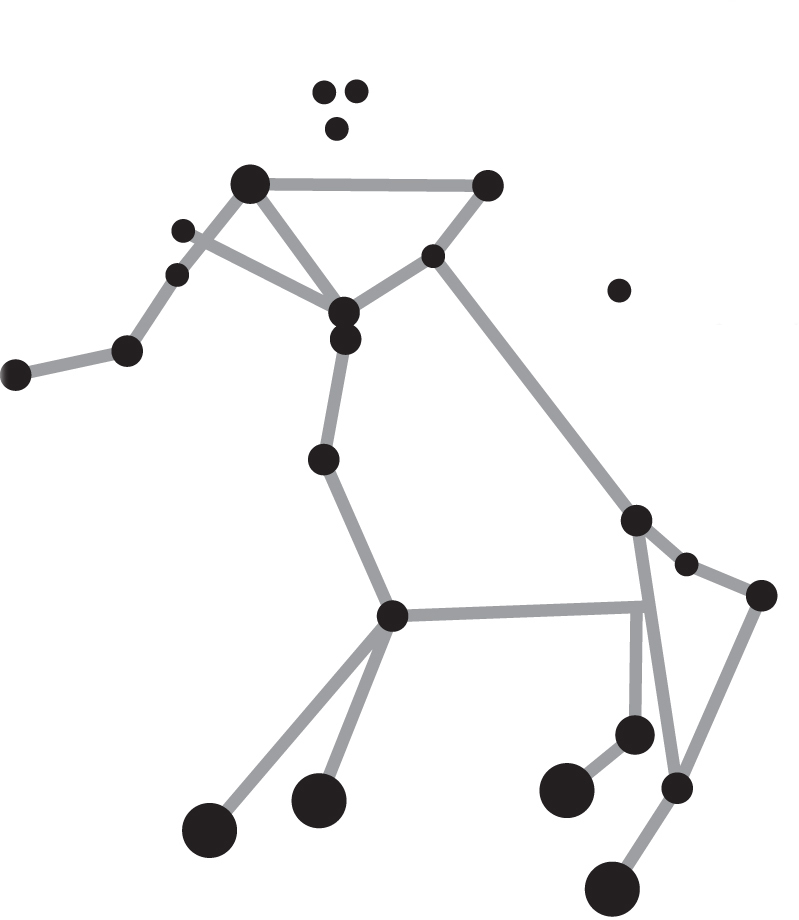

As earthbound mortals mourned the tragic loss, the gods gathered and agreed to honor Chiron in the eternal heaven. His constellation—simply called the CENTAUR—stands tall on four legs and walks with a stately gait through the celestial sphere. In his hand he holds a WILD ANIMAL—a savage stalker of his forest home, which most perceive in the shimmering sky as a wolf. The stars show Chiron clasping the hind feet of the beast in his right hand. In the left, he carries a thyrsus (a staff adorned with leafy vines and pine cones) in devotion to Dionysus, the god who likewise loves to wander the wooded mountains.

Crotos and Chiron both gained the timeless praise of immortals and men. Both embodied the qualities that Hellenes most admire: skill at arms and in the arts; valor devoid of vanity; an adventurous and enlightened spirit; knowledge and wisdom; compassion and piety. They portrayed the essence of arete. Appropriately, the two appear in the sky as they approach, in reverence, the Incense Altar of the gods. In proper display of their personalities, Chiron is shown in solemn procession and Crotos in joyful dance.

THE END OF A GOLDEN ERA

Crotos and Chiron lived their lives during glorious times for mortals. But golden ages must come to an end, and centuries sometimes lapse before they appear again. Mortals, male and female, young and old, alas, fell into the folly of conceit. They came to consider themselves the center of all creation. In blind lust to rule the world, they soon lost sight of their oneness with nature and the spiritual essence around them.

The beauty of Astraea’s divine blessings—of virtue, peace, and plenty—dimmed in a fog of ingratitude. At last, the goddess found herself alone—ignored as if invisible—without the laughter and love of her earthly children. Weeping at their woeful deeds, and the dreadful consequence sure to come, she fell into deep despair. Sobbing in soulful lament, she left the world behind and ascended into heaven with a broken heart.

Without her peaceful presence, human greed for power and possession brought the horror of hatred and war among them. And so began the sordid age of the restless workers of bronze, “who were the first to forge the sword . . . and the first to eat of the flesh of the plowing-ox.”9 Without a divine beacon and a moral ethos as their guide, they turned on each other like wolves—“and they slaughtered with the bronze.”10

The kingdoms of Hellas and Asia now warred with one another from one side of the Aegean Sea to the other. Some blame the Phoenicians or Persians of Asia for instigating these wars of old. Others accuse the Hellenes. Herodotus, the historian, recorded the Persian account that said a crew of Phoenician sailors arrived at Argos one day. Here, they planned to barter their Asian goods for olive oil and purple wine, and the painted pottery of Hellas. After several days of successful trade, the sailors prepared to depart.

As they rigged the ship and coiled the lines, they suddenly grabbed several girls of Argos who had come to the docks to shop. Before there was time to react, the Phoenician crew caught a freshening breeze—a favorable wind from the west—and fled far over the eastern horizon. One of the mournful, captive maidens was none other than Io, the princess of Argos. Her father, the king, was furious and demanded revenge for his daughter’s abduction.

This was the Persian story. But Hellenic traditions tell us that Io was captivated by Zeus. The covetous god made love to the maiden, then transformed her into a snow-white heifer to hide and protect her from Hera, his jealous wife. But Hera knew the ways of Zeus and soon saw through the disguise. In a fit of fury, she sent a gadfly to chase the girl far from her native home.

With the biting fly in hot pursuit, Io ran bucking and kicking along the shore of the Ionian Sea, which bears her name. From there, she sped eastward and swam the Bosporus—or Cow Ford—which carries her name as well. Finally, she fled far to the south, leaving the gadfly behind, and found a safe haven in Egypt. Located at last in the land of the Nile, Zeus restored Io to her former youthful figure. Or so goes the Hellenic tale.

According to the Persian account, after Io’s abduction from Argos, a Hellenic merchant ship crossed the Aegean Sea and moored at the Phoenician port of Tyre, on the Asian coast. Upon completing their commerce, the crew abducted Europa, a princess of Tyre, in retaliation for Io. Not long later, another crew of Hellenic sailors, trading at the eastern city of Aea in Colchis, absconded with another Asian princess, named Medea. Of course, Hellenic versions vary, as we shall see.

The Persians claimed that this double abduction of eastern princesses prompted Paris—the prince of the Asian city of Troy—to capture Helen, the queen of Sparta in Hellas. With beautiful Helen whisked away to Troy, the kings of Hellas reacted in wrath and rage. Together they launched a thousand ships filled with their fiercest warriors. Sailing eastward across the Aegean Sea, they planned to retrieve the Spartan queen and to plunder the prosperous city of Troy.

For ten bitter, tempestuous years they waged their war. Blood from countless battles stained the sand from the city walls to the Hellene tents and ships on the shore. The furious fighting “sent down to Hades many valiant souls of warriors, and made the men themselves [the lifeless bodies on the beach] to be the spoil for dogs and birds of every kind.”11 In the end, proud and prosperous Troy lay in wreck and ruin—smoldering and choking in ash and smoke.

Paris, Prince of Troy, had acted like the greedy dog in Aesop’s fable. The dog had all the meat he could eat clutched firmly in his mouth; but he lost it all when he opened his jaws to grab for even more.12 Paris had the royal wealth of Troy at his disposal; but, by taking Helen, he lost his life and the lives of many thousands.

As a legacy, he left his ancestral land in desolation. Still worse, the Trojan War sparked eight centuries of conflict between the empires of Asia and Hellas. Hundreds of thousands of mortals—belligerent and blameless alike—died on both sides.13

The same disdain for humans and gods that kindled the Trojan War also caused the armies of Hellas to further provoke the divine wrath. Odysseus and his Ithacan army had joined their Hellenic countrymen in the ten-year quest to conquer Troy. In the final months of fighting, Odysseus—clever and cunning as ever—devised the victory by building a massive wooden horse. Leaving it alone to tower above the sandy shore, as if an offering to Poseidon, the Hellenes launched their fleet and headed for home.

When the Trojans discovered their hasty retreat and the huge horse looming above the beach, they shouted aloud in triumph. Quickly, they hauled the wooden hulk inside the city’s impregnable walls and placed it as a gift in Poseidon’s temple. After a day of drunken debauchery, the city slept soundly that night.

Unknown to them, the lifeless horse bristled with bloodthirsty Hellenes—crowded into every corner within. Then, when all was dark and quiet, the waiting warriors stealthily slipped to the ground and opened the city gate for the returning Hellenic army. Ten years of bitter rage at last became unleashed as the Hellenes ruthlessly slaughtered Trojans—men and women, young and old. For this massacre, and for the mock offering of the horse, Poseidon promised to punish the mastermind—Odysseus—when he sailed for home on the stormy sea.

Thus it happened that Odysseus won the war only to be “driven far astray after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy.” While trying to return to his island kingdom of Ithaca, Poseidon condemned him to wander the merciless waters for ten more years. All the while, Odysseus endured endless hardships and close encounters with death. Many were “the woes he suffered in his heart upon the sea, seeking to win his own life and the return of his comrades” to Ithaca—where his long-suffering wife, Penelope, patiently waited.14

THE BEAUTIFUL ISLAND OF SORROW

Odysseus and his starving men, while lost and adrift on the angry sea, made sudden landfall on the gentle, sloping shore of a sunlit island. This paradise in the middle of the Mediterranean bore the name Thrinacia, because of its strange triangular shape. Centuries later, sailors from Hellas would find the island rising, beautiful to behold above the surging sea, and rename it Sicily.

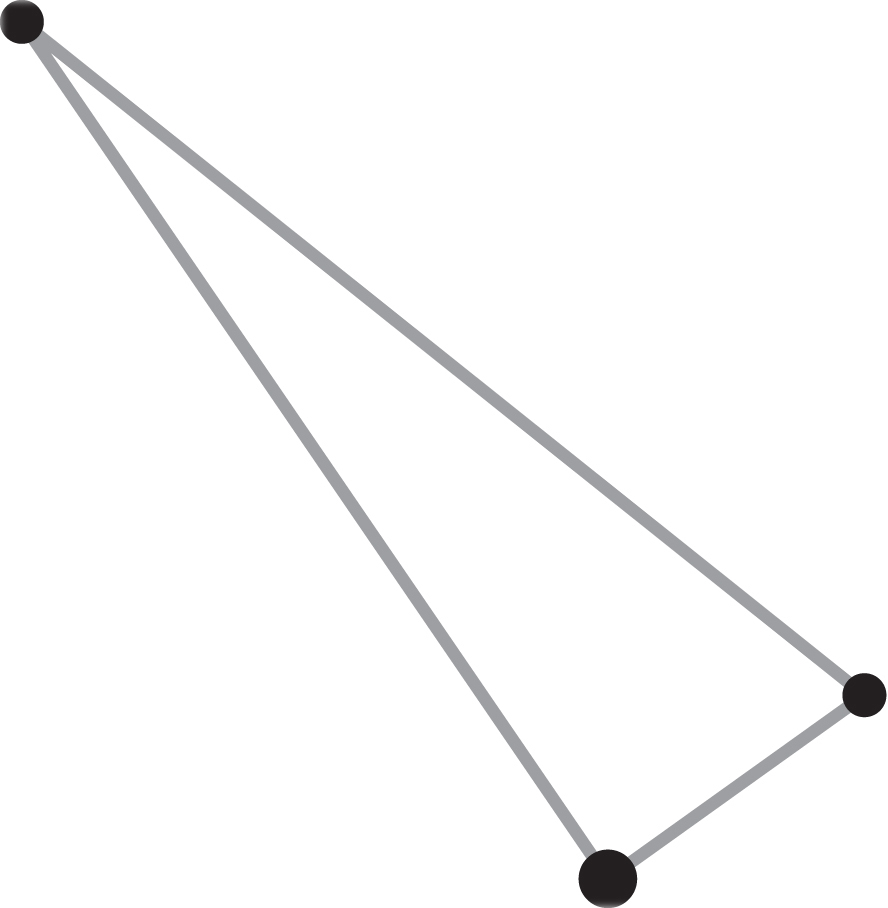

At one time, the island offered a favorite haven for immortal gods.15 Here, Apollo kept his handsome herd of sacred cattle, safe and secluded. Like Apollo, Demeter—the goddess of farming and harvest and protector of green and flowering plants—loved the island for its lush verdure and pastoral charm. She even called on Zeus to honor the pleasant isle in heaven, where it shines as a simple TRIANGLE bound by three stars.16

But sorrow soon followed on Thrinacia. Demeter’s dreamy daughter, Persephone, loved to wander with her maiden friends through the island’s dewy meadows, laughing softly and gathering fragrant flowers. Her soothing voice and glowing countenance captured the heart of Pluto—the god of the underworld. Pluto rarely witnessed anything other than darkness and death. But from the depths of a shadowy chasm, he often watched the girl’s delightful form as she glided on dainty feet through the glistening fields.

Triangle |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Triangulum |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

β Trianguli |

02h 09m 33s |

+34° 59′ 14″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

One sunny day, Persephone spied a colorful blossom dancing in the breeze near a deep crevice. Lured by its beauty, she left her maidens and hastened to the beckoning flower. As she approached, Pluto burst from below and carried the frightened girl to his dreadful domain to make her his wife.

Demeter, on learning of her daughter’s abduction, wailed in heartfelt anguish day and night. Again and again, she pleaded with Zeus to punish Pluto and return her daughter to her tender embrace. Zeus, in time, intervened. But he could only compel his brother, Pluto, to allow Persephone to spend half of each year with her mother in the delightful world she loved. Thus, for six months, as Demeter grieves for her daughter, the cold darkness of winter descends upon the earth. But with the return of Persephone to her mother’s arms each spring the earth abounds in flowering plants and the songs of birds.

Tragedy struck again on Thrinacia when Odysseus’ famished men ignored their king’s strict command and killed and ate some of Apollo’s sacred cattle. For this sacrilege against the gods, and for rousing the wrath of Apollo, Odysseus and his crew ran headlong into a fearsome storm as soon as they sailed from the peaceful island. As the crashing waves cracked the beams and shattered the ship into splinters, every member of the crew floundered and drowned in the dark and swirling waters.

Only Odysseus, who abhorred the actions of his men and prayed for divine forgiveness, was spared. But still he suffered the woe of being the sole survivor of the proud Ithacan army that had sailed for Troy so many years before. As further punishment, the deities delayed his homeward return for several years more.

THE GREEDY CROW OF APOLLO

Men were not the only mortals to fail in their devotion to the gods, and suffer the result of divine wrath. Even a few of the animals most trusted by the Olympians fell out of favor for putting their own interests first. Such was the case of the Crow—Apollo’s favorite bird and close companion.

One day, Apollo called on the Crow to bring him water from a sparkling pool on Mount Olympus so he could offer a holy libation. In those days, the immortals often affirmed their allegiance to one another by pouring pure drops of water as a sign of esteem. This was long before wine was invented and used for the same purpose.

The Crow swiftly obeyed Apollo and seized a gleaming Crater—the goblet of the gods—in his talons. Searching high and low, the Crow scanned the slopes for a spring that offered a draft of water worthy of a divine libation. Soon he arrived on the shady bank of a shining pool. As he began to fill the Crater with crystal clear water, his gaze fell on a voluptuous fig tree bending low with the weight of its fruits.

Hungrily, greedily, the Crow hopped from limb to limb, waiting for the figs to fully form so he could fill his belly before returning to Apollo. One day turned into two, and two into three. Finally, the fruit was ready—plump and ripe—and the Crow gorged himself with delight.

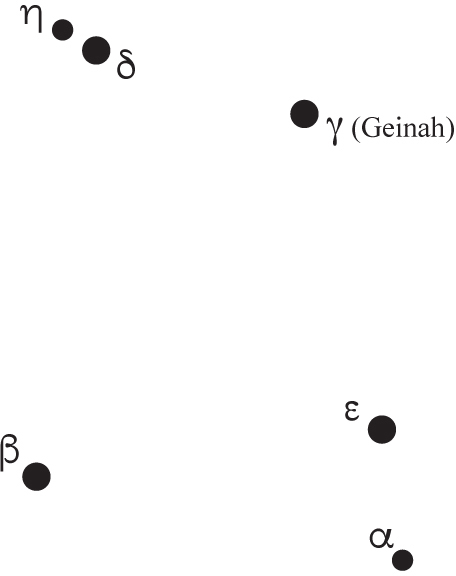

Crow |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Corvus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Geinah |

12h 15m 48s |

–17° 32′ 31″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Crater |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Crater |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

δ Crateris |

11h 19m 20s |

−14° 46′ 43″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

With his appetite now satisfied, he began to ponder Apollo’s reaction to his impulsive delay. After a moment’s hesitation, he grabbed the Crater in one claw, and in the other a wondrous water snake that guarded the sacred spring. Then he flew fast and true—with all possible speed—to Apollo.

His head remained bowed and his eyes cast down as he tried to explain his lengthy stay at the spring. With many reluctant stops and starts, he told a tale—how the huge snake had drunk the water dry, day after day, and kept him from filling the goblet. But Apollo could not be so easily fooled. He punished the Crow and all of his kind by making them go without water for days at a time, with dry and cracking throats, and rasping calls. While they soar above the fields and forests, they caw aloud for a soothing draft to quench their nagging thirst.

Furthermore, as a warning to those who choose to put their personal greed before the gods, Apollo placed the CROW in the nighttime sky. There, the boisterous bird, with wings held high, pecks at a serpent—much like the snake at the spring. Just out of reach of the Crow is the starry CRATER, holding a cool draft of crystal clear water.17