3

WOEFUL DEEDS OF THE WANTON GODS

CONSTELLATIONS

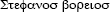

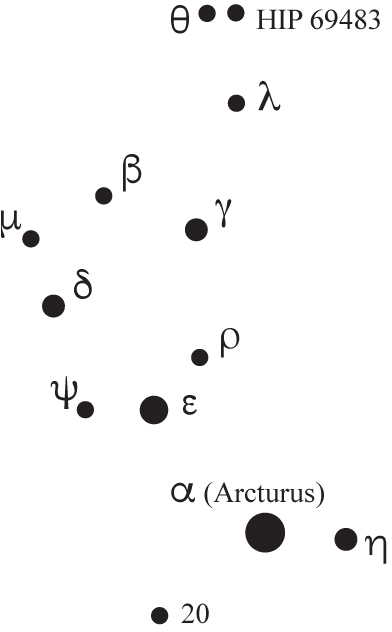

NORTHERN WREATH (Corona Borealis)

ASTERISMS:

PLEIADES (Pleiades)

HYADES (Hyades)

STAR

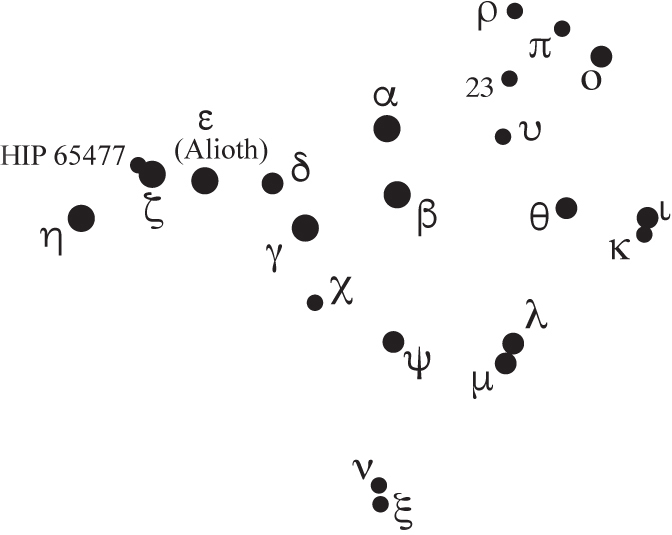

BEAR GUARD (Arcturus)

As mortals came to disdain their fellow beings and divine deities, selfish struggle and strife drove them to war among each other. The gods—indignant—fumed in anger. Even Astraea, who had loved humans as innocent children, walked away in sorrow. Zeus himself, who had chuckled in mirth at the childlike folly of men, now turned bitter toward them and became capricious and cruel. Innocent people suffered along with the rest, as the stories of Callisto, Arcas, and Phoenice attest.

CALLISTO, THE MOUNTAIN MAIDEN

In the distant past, the maiden Callisto dwelled among the dark forests and jagged crags of Arcadia. Hermes had been born in this wild and rugged country, in a rocky cave on Mount Kyllene. And Pan—“the goat-footed, two-horned rowdy,” the patron of savage beasts and shepherds’ flocks—still haunted the deep hollows and dizzying heights.1

The mysterious mountains enchanted Callisto. She often wandered, beneath the moon, through meadows glowing in subtle light and forests shrouded in shadows. In euphoric suspense, she sometimes stopped and stood silent and still in the darkness. She listened intently and peered through the gloom for a glimpse of the wild and wary creatures that prowled around her.

Callisto followed, in firm devotion, the divine example of Artemis—goddess of the hunt and matron of the moon. Artemis, too, delighted in spending days and nights softly stalking through somber forests in search of game. The goddess—a virgin—also championed female chastity, and Callisto had sworn to abide by that code. But the dictates of fate were not for her to decide.

One morning, while Zeus was seeking solace in the dusky woods, he spied Callisto from a distance—gliding silently from tree to tree and fully focused on the hunt. The maiden remained unaware of his presence as he followed her through the forest, until he met her face to face. Unable to fend against his advances, she conceived a child and gave birth the following spring to a son.

Forlorn, and afraid of Artemis’ anger at the conception and birth, Callisto bundled her baby and held him close—concealed in her cape. But the virgin goddess heard the crying child and found that the girl had not remained chaste. In misplaced rage, she rashly blamed Callisto for the indiscretion.

As punishment, Artemis snatched Callisto’s son away and transformed her from a graceful youth to a blundering bear. Her tender voice became a grumble and growl. Her silky hair turned course and matted, and covered her body from head to foot. Condemned to ramble the woods on four feet, as a brutish beast, Callisto was constantly hunted by her own countrymen. The barking of dogs and shouts of the chase that had filled her with thrills and excitement now brought fear and foreboding.

Many loathsome, lonely years passed, and Callisto’s infant son—Arcas—grew to be a sturdy youth. Raised by a rustic goatherd in the rugged heights of Arcadia, Arcas earned his keep with a drove of goats and sheep, and the meat he brought home from the hunt. One calm morning, while his flock lazily grazed beside a trickling spring, he spotted a she-bear on the shadowy fringe of the forest.

With a leap and a yell, he gave chase, unaware that the bruin was his own woeful mother. All that day, he pursued the frantic beast through brambles and brush, down rocky ravines, and across cold mountain streams. At last, he wore her down. As she lay exhausted before him, her head on the ground, with pleading eyes turned upward, he held high his club to deliver the fatal blow.

The loud shouts of the hunter and the lamentations of the bear caught the attention of far-seeing Zeus. As he watched the tragic drama unfolding below, he felt sudden pity for Callisto and Arcas—his long-lost lover and child. In haste, he forestalled the evil fate that threatened to make one the victim of her son and the other the murderer of his mother. There, on the leafy forest floor, with a word from Zeus, the two suddenly knew their true relation, and, overawed, rejoiced in the reunion.

From that day forward, Callisto—who knew every haunt and hollow—led the way down hidden trails as she and Arcas wandered far and wide through the forest. Arcas always followed close behind, faithfully protecting his mother. Finally, to offer her safety and solace forever, Zeus placed her in the highest heaven, where she shines as the constellation Arctos—the BEAR.2 Here she circles the north celestial pole in peace, with none to fear. And yet she keeps a wary eye on the stars that mark the hunter named Orion.

Bear |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Ursa Major |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Alioth |

12h 54m 02s |

+55° 57′ 35″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

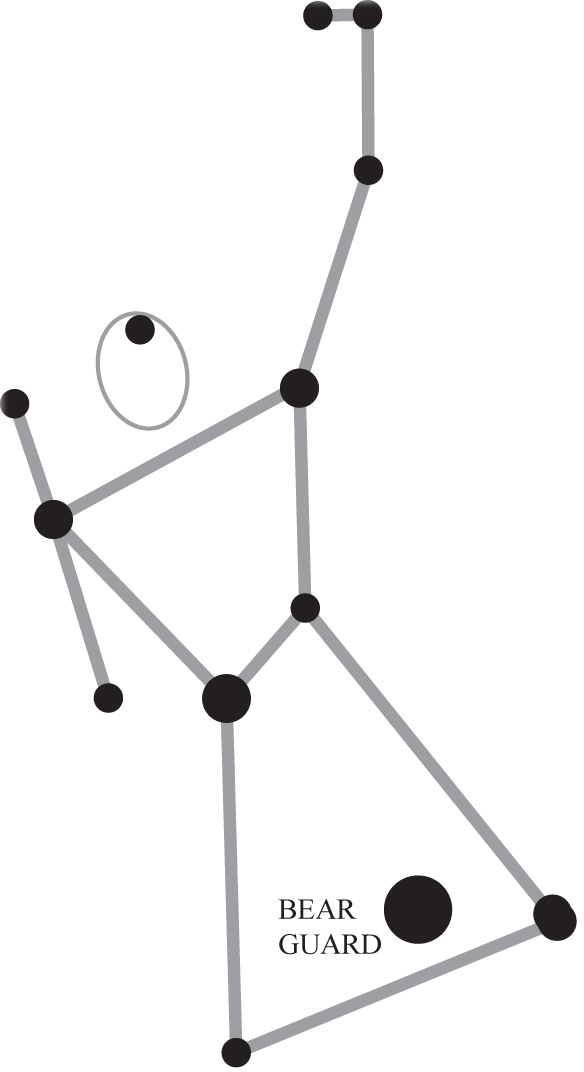

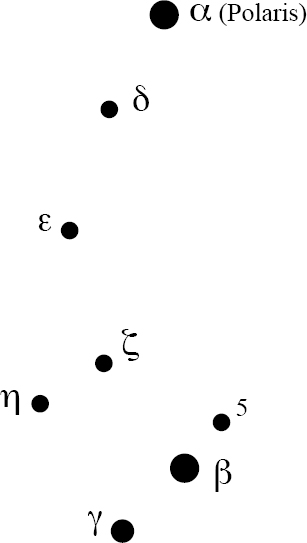

Arcas came to rule the rugged mountain kingdom, which was later named Arcadia in his honor. He lived a long and happy life in his forest home while shepherding his people well, and forever revering his lustrous mother above. When he came at last to the end of his days, Zeus set him in the cosmos as the Bear’s protector, and called him BOOTES—the Shouter.3 His brightest star is Arcturus—the BEAR GUARD—so named because of his constant watch over his mother’s constellation. With a shepherd’s staff in the right hand and his left hand reaching fondly toward her, he follows close behind in the northern sky.

When Zeus intervened to reunite the mother and son, Artemis at last learned the truth—that Callisto conceived the child through no fault of her own. In deep remorse for her unfair judgment and brutal reprisal, the goddess bowed her head in shame. Too late to make amends, she vowed to never take that path again.

Bootes |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Bootes |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Arcturus |

14h 15m 40s |

+19° 10’ 56” |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

In years to come, Zeus, the wanton god, lustily followed Phoenice—another faithful admirer of Artemis. Phoenice—a daughter of the Phoenician race—was much like Callisto in manner and morals. No sooner had Artemis detected Zeus’s threat than she took fast action to protect the innocent girl. Reacting in pity, rather than rage, the goddess changed Phoenice’s feminine form into that of a bear before any further harm could come.

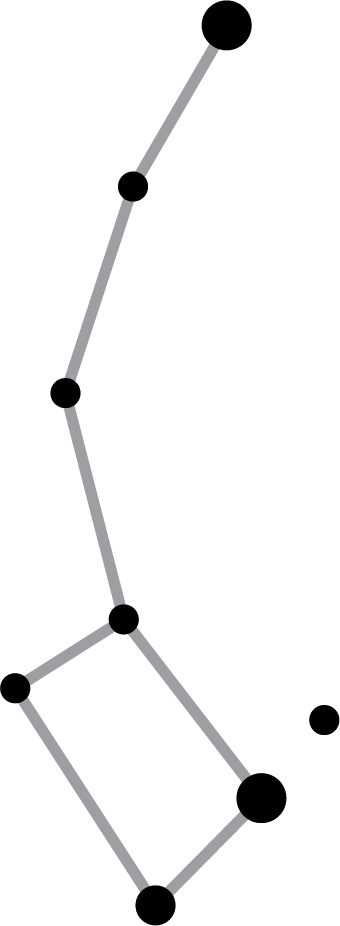

But Phoenice was never forced to wander the woods in fear, like Callisto. Instead, Artemis set her securely in the sky as a constellation, in close company with her larger companion—the Bear. To distinguish the two, Phoenice is called the LITTLE BEAR. At the apex of heaven, she stalks swiftly forward through the night in a rapid circle, above the back of the Bear. The two stand out from earthly bruins because of their long and splendid, starry tails. The Little Bear’s tail curves upward, so she sometimes carries the nickname Cynosura, or “dog-tail.”4

Little Bear |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Ursa Minor |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Polaris |

02h 31m 49s |

+89° 15′ 51″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

THE SEDUCTIVE SWAN

Zeus continued to pursue mortal women. To seduce them, he sometimes dazzled their senses and captured their affections by appearing in the form of a magnificent animal. As a spectacular, snow-white swan, he captivated the love of Leda of Sparta. Soon she bore him twin sons—Castor and Polydeuces—and daughters, Helen and Clytemnestra.

The two boys later emerged as heroes of Hellas and journeyed with Jason and the Argonauts. Helen gained renown for her unrivaled beauty, and married Menelaus—the king of Sparta. Her abduction to Troy sparked the Hellenic conquest of that prosperous and powerful city. Helen’s sister, Clytemnestra, wed the brother of Menelaus—King Agamemnon of Mycenae—who commanded the seaborne invasion.

Bird |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Cygnus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Deneb |

20h 41m 26s |

+45° 16′ 49″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Zeus celebrated his liaison with Leda by placing a constellation, called the BIRD, in the sky in the shape of a swan. The swan shines bright among the dense assembly of stars in the glowing Milky Way. There, he appears as if “wreathed in mist” and soaring “like a bird in joyous flight.”5

EUROPA AND THE BULL

Zeus assumed the shape of another stunning creature—a snow-white bull—to win the affections of the maiden Europa. From childhood, the cheerful Europa had always loved the coastline of her native Phoenician home, much as Callisto adored the forested mountains of her land of birth. Europa often wandered along the Asian shore, laughing at the splashing surf and savoring the salty breeze. She watched for delicate seashells and other treasures dropped at her dainty feet by the benevolent sea.

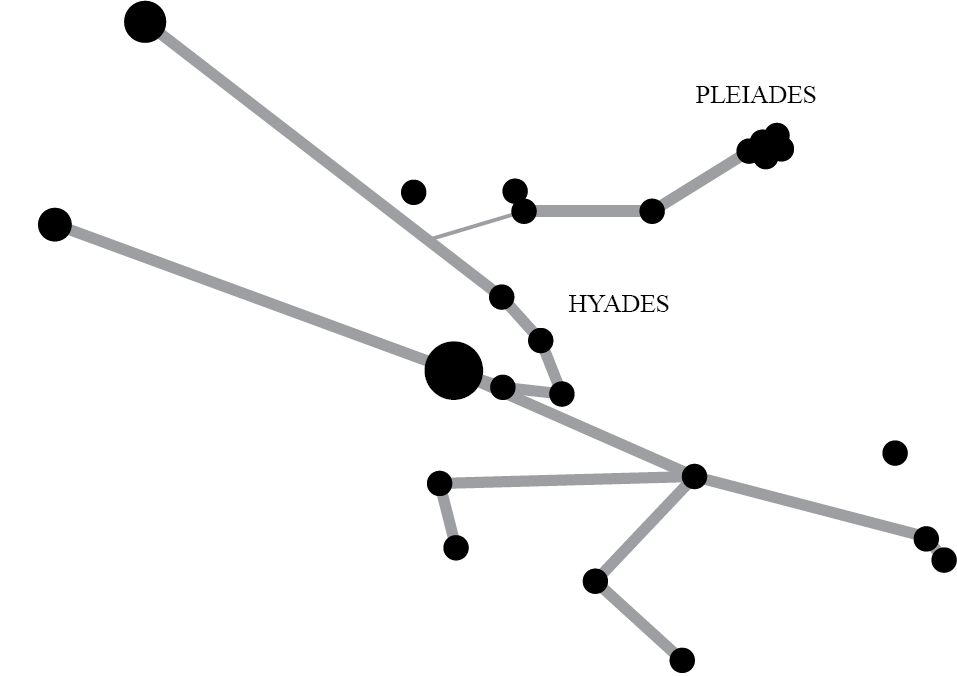

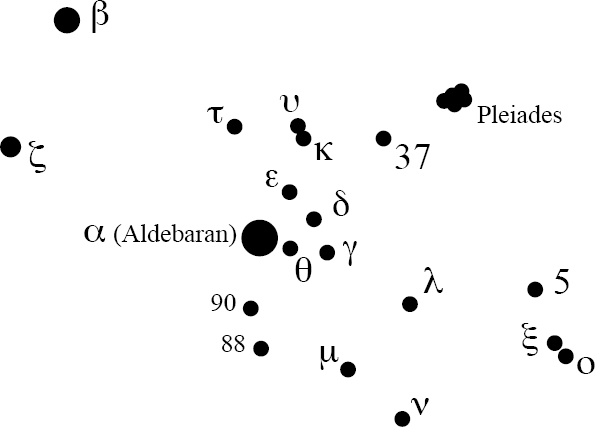

Bull |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Taurus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Aldebaran |

04h 35m 55s |

+16° 30′ 33″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

One warm day, as Europa strolled along the balmy Mediterranean beach, she froze in her footsteps—entranced by the sight of a beautiful bull, grazing the seagrass near the shore. Approaching slowly, she petted the blond, curly locks between his horns. She picked pretty flowers and fashioned a garland to adorn his head. Finally, she grasped his supple mane and slipped atop his broad back for a wade in the rolling surf.

Suddenly, the docile bull sprang to life and lunged into the waves. Swiftly he swam, rapidly plunging through the waters toward the west—sweeping Europa out to sea. As she desperately clung to his curly mane, she glanced behind and watched in dismay as her homeland dwindled and finally disappeared.

The island of Cyprus soon loomed ahead. But the bull continued to batter the waves, bounding toward the setting sun. At dusk, the island of Crete came into view. As they approached, it seemed to swell on the horizon. Here, at last, the bull with his maiden prize waded ashore to rest on the sandy beach.

Europa collapsed near the crashing surf, sobbing in woe and foreboding, and homesick for her family. But the charming island enticed her to wander its pleasant shores. By and by, she found that graceful beaches surrounded the elegant land in all directions. Her sorrow now gave way to glee as the shorebirds sang her a welcoming song, and a gentle sea breeze softened her tears.

Crete soon captured her heart and became her adopted home. The following year, she brought forth a son and named the baby Minos. As a toddler, the child—the son of Zeus—traipsed hand-in-hand with his mother along every sunbaked beach of the island. And, like his mother, he treasured the gifts of the sea.

While still a youth, he hiked the hills alone and came to love the land—every cave and cliff, every mountain, meadow, and forest. Soon he knew all the native beings of the island, the plants, animals, and people, by name. So no one seemed surprised when, one day, Minos—the son of Europa and Zeus—reigned as king of Crete.

Zeus was pleased to see the happiness of the mother and son. In satisfaction, the powerful god—ever proud of himself—commemorated his cunning theft of Europa by placing the BULL in the nighttime sky. The majestic beast blazes among the stars, half-submerged and splaying his forelegs in the same manner that he swam the heaving sea.

The Bull is called a constellation “rich in maidens,” because he bears several sisters on his back, just as he once bore Europa. The seven sisters, called the PLEIADES, appear as seven stars that ride high on his hump as an asterism. Their five half-sisters—the HYADES—shimmer as heavenly lights on his head.6

THESEUS AND ARIADNE

Minos ruled the people of Crete with fairness. But he fell into the common folly—far too often repeated—of showering his affection on one of his several children, to the detriment of all else. In fact, Minos adored his son, Androgeus, more than the rest of his family, his friends, and his entire kingdom.

Under his father’s constant attention, with lavish expenses for coaches and training, the boy developed into a talented athlete. When Androgeus traveled to Athens and won the victory at the Panathenaic Games, all of Crete rejoiced beside the beaming father. But many Athenians fumed at the thought of a foreigner wearing the triumphal wreath of their city.

Several ruffians banded together in the dark and inflamed each other with angry words. Then, in a fit of fury, they followed Androgeus and crowded close to kill the youth. The people of Crete reeled when they heard the hated news. Minos locked himself in his palace—unseen for days—distraught beyond words and weary of the world’s evil ways.

At last, his sorrow surrendered to rage. In brutal retaliation, Minos imposed a terrible tribute on Athens. The wrathful king forced the fair city to send seven of its sons and seven of its daughters as annual sacrifices to the man-eating Minotaur.

The monster, half-man and half-bull, dwelled in the deep, dark labyrinth—the twisted maze of Cretan caves. Alone in that dreary domain, the hideous, half-starved creature raged within his wretched world, bellowing day and night for another screaming victim to meet his miserable fate.

If the Athenians failed to pay the horrid tax of human flesh, Minos—the powerful King of Crete—promised to burn their city and level their land. For many years, Athens had no option but to pay the dreadful debt. As yet another year approached, the Athenian Councilmen, wringing their hands in anguish, tried to decide which of their fair children to send to their gruesome deaths.

At that moment, a brash young man named Theseus stepped boldly forward. To their speechless surprise, he proposed to journey to Crete as a would-be sacrifice. There he would battle the beast and win a cease to the grisly tax. The Councilmen opposed the plan in theory, but not enough to dissuade themselves of its merit. In the end, they accepted Theseus’ offer.

Soon the Athenian ship, with its confident hero and crew, and thirteen tearful boys and girls, found its way across the wine-dark sea to moor on the coast of Crete. Theseus—tall and fiery—was first to set foot on the sandy shore. Immediately, without his knowing, he captured the eyes and heart of Ariadne—the daughter of Minos.

Without hesitation or need for further thought, the Cretan princess determined, then and there, to save the handsome youth from the Minotaur. As the curious crowd of gawkers departed and an opportunity arose, Ariadne sidled close beside him. Softly, she whispered hurried words of advice in his ear, and slipped him a simple ball of thread.

Thus armed, Theseus entered the labyrinth the following day with confidence, while his companions trembled and wailed at the entrance. Leaving them there, he silently stole through the gloomy cavern. As he slipped warily forward, he unwound the spool along the path to provide a guide for escaping the twisted lair.

Far down the dismal route he wandered, passing fly-infested heaps of putrid bones. Suddenly, he stumbled upon the foul fiend in the darkness. The battle raged, with the two powerful enemies beating and butting each other until they fell to the blood-soaked floor exhausted. Heaving and frothing, Theseus was first to regain his strength and catch his breath. With bare fists, he pummeled the Minotaur until the monster’s eyes glazed over in death.

Now the hero made his slow escape, following a simple, indispensable string—his lifeline from the mind-numbing maze. As he staggered out of the somber gloom, he shaded his eyes against the bright and cheerful light of the sun. From somewhere near, the other Athenian youths, still shaking with fear, heard the frightening sound of approaching footsteps. But soon they stared in disbelief, then cried in overwhelming relief as their comrade came into view. Ariadne, having saved Theseus by a thread, rejoiced in silence from her hiding place in a nearby grove of trees.

Undetected by the palace guards, Theseus and his thirteen friends dashed toward the Athenian ship where the hopeful crew awaited. Beside them ran the Cretan princess. Her mind firmly fixed, Ariadne abandoned her father and country and sailed in haste with the hero, in hope of a new life in Athens.

At mid-voyage, while resting on the island of Naxos, the maiden—her body, mind, and emotions fully exhausted—fell into deepest slumber. For long hours she laid so silent and still that Theseus feared she had passed into peaceful death; every attempt to revive her failed. Finally, with his happy heart now broken, Theseus left her lying in sweet repose and resumed the long journey without her.

With judgment clouded by grief, he forgot the promise he had made to his father to hoist a white, billowing sail as the ship approached the Athenian shore. The sail was to serve as a signal that Theseus had found his way home, alive and well. Instead, as he slept, the unknowing crew sailed the ship close to the coast with the traditional black sail of mourning hoisted high on the mast.

Theseus’ father had silently sat, day after day, with his eyes fixed on the horizon. At Poseidon’s temple at Sounio, on a precipice above the sea, he watched and waited for his son’s return. When in the distance he saw the dreaded canvas, billowing black above the sea, he knew it meant that Theseus and the thirteen youths had fallen to the ferocious Minotaur.

In sorrow and despair, he cast himself off the cliff, into the churning waters below. When Theseus stepped ashore, he heard the horrid news. At once, his victory evaporated—like a fresh drop of rain on a blazing summer day—whisked away by the double tragedy of losing his father and Ariadne.

Back on the island of Naxos, Ariadne finally awoke to find her loved one gone, and herself alone. The poor girl could not be consoled. In so short a span, she had lost her beloved hero, her family, her friends, and her homeland.

Her mournful sobs and deep distress attracted the attention of the god, Dionysus. In pity for the trembling maiden, he soothed her brow and stroked her hair, and soon fell fast in love. At last, she set her sorrow aside and vowed to go with him to the heights of Mount Olympus to be his bride.

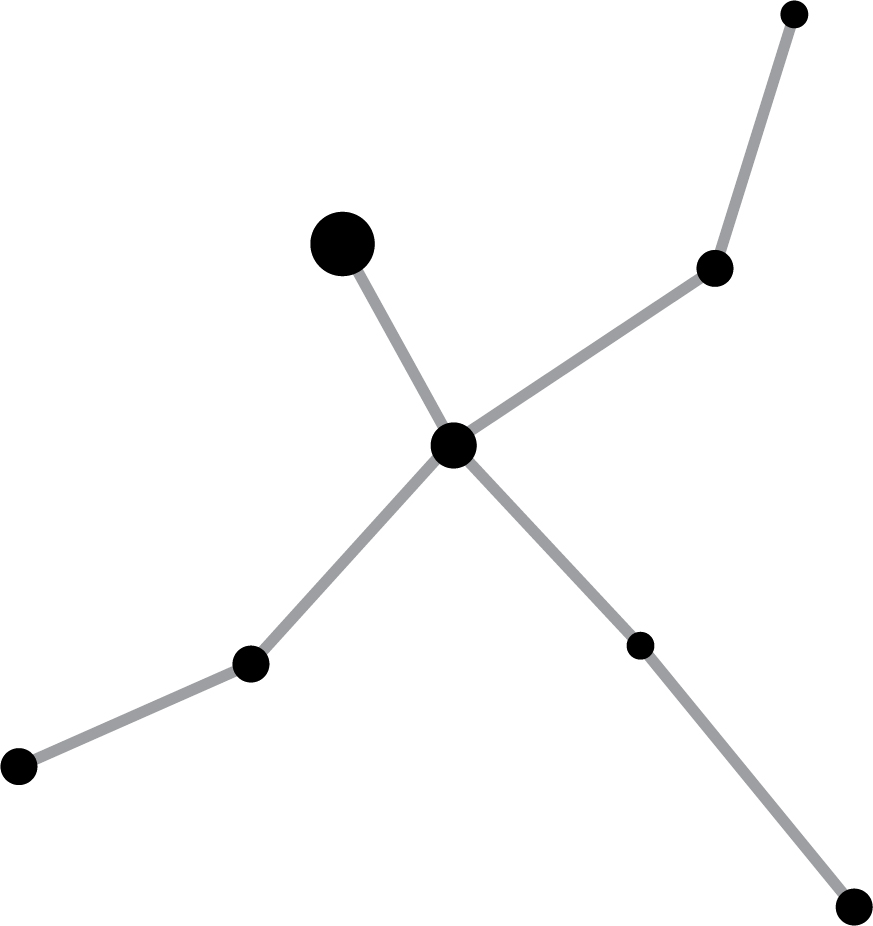

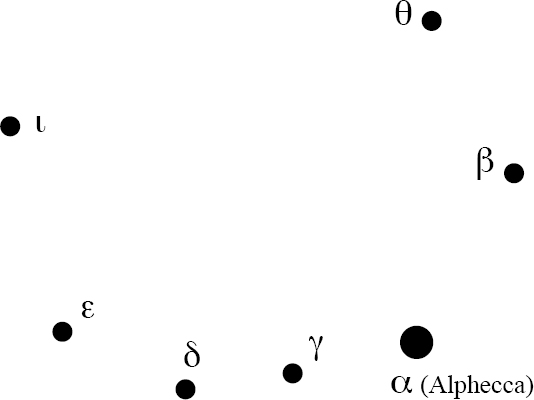

There, the delightful wife of Dionysus became a favorite among the immortals. Many years later, when Ariadne passed away, all of Olympus mourned. Dionysus, in deepest sorrow, set his loved one’s wedding wreath among the stars, where it still blazes from afar as the NORTHERN WREATH—a befitting tribute to beautiful Ariadne.7

Northern Wreath |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Corona Borealis |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Alphecca |

15h 34m 41s |

+26° 42′ 53″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

In the age of bronze, the belligerence of mortals and gods brought countless sorrows upon the Earth. But in the end, good prevailed. Zeus’s seduction of Leda was shameful; but the resulting birth of the twins—Castor and Polydeuces—provided the world with two heroes who faithfully served both gods and men. Likewise, his abduction of Europa was a dastardly act, but it led in later years to the birth of a granddaughter—Ariadne. The sweet and gentle girl saved the lives of Theseus and thirteen other Athenian youths, while helping to rid the world of the monstrous Minotaur. As Dionysus’ wife, she delighted the gods and gained their everlasting love.

Zeus—forever the philanderer—fathered other children by three of the seven sisters known as the Pleiades. But, once again, good prevailed in the end. The three children born of these trysts rose to greatness among immortals and mortals alike. Maia, the fairest of the Pleiades, brought forth the infant Hermes, who later flew through the sky as the messenger god so dearly loved by humans. Maia’s sister, Taygeta, bore a son named Lacedaemon, who founded the kingdom of Sparta. Electra’s son, Dardanus, became the father of the Trojan race. These children offered further proof that good may come from even the basest beginnings.