4

THE PRICE OF ARROGANCE

CONSTELLATIONS

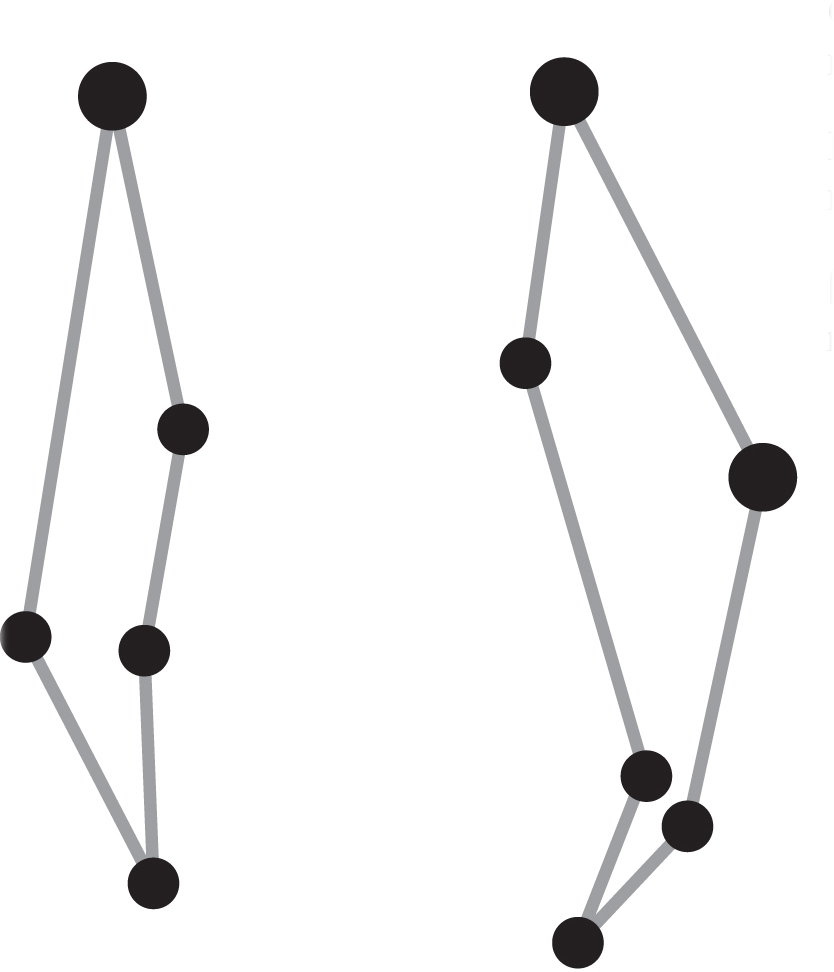

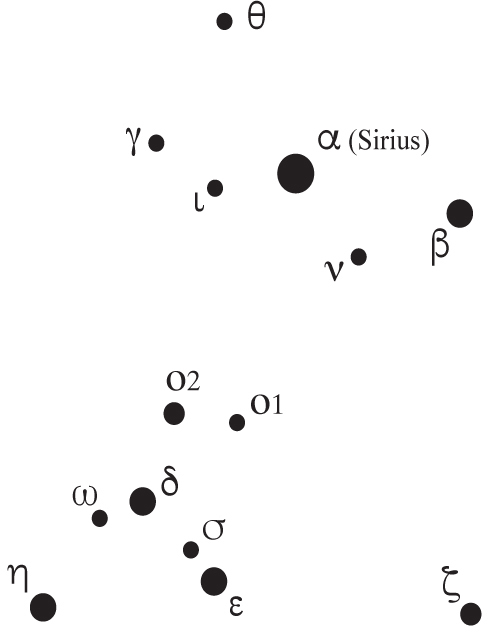

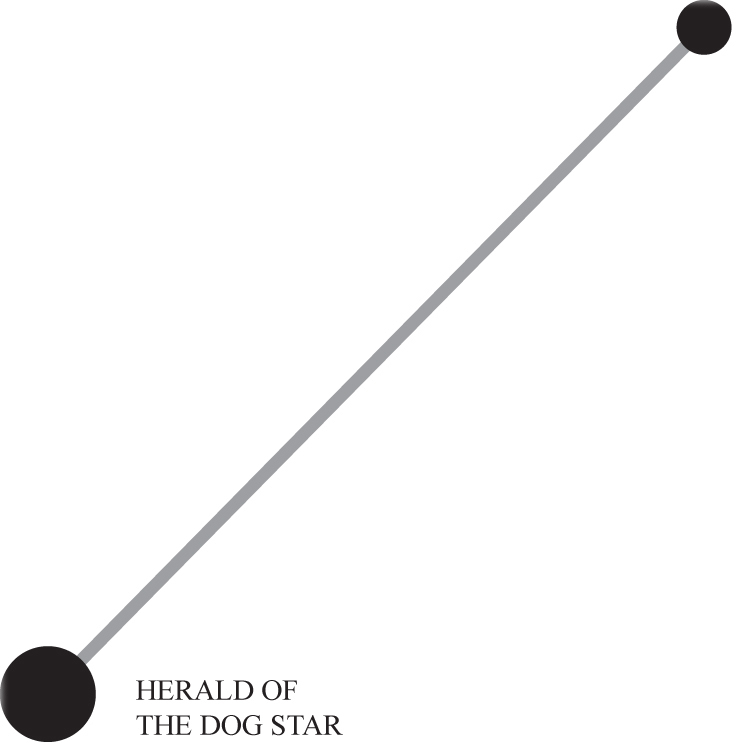

HERALD OF THE DOG (Canis Minor)

STARS

DOG STAR (Sirius)

HERALD OF THE DOG STAR (Procyon)

The gods had come to disdain mortals because of their failure to offer proper respect and devotion. Arrogance, above all, provoked the deities, because it created strife among humans and made men believe they outshone all beings, mortal and divine.

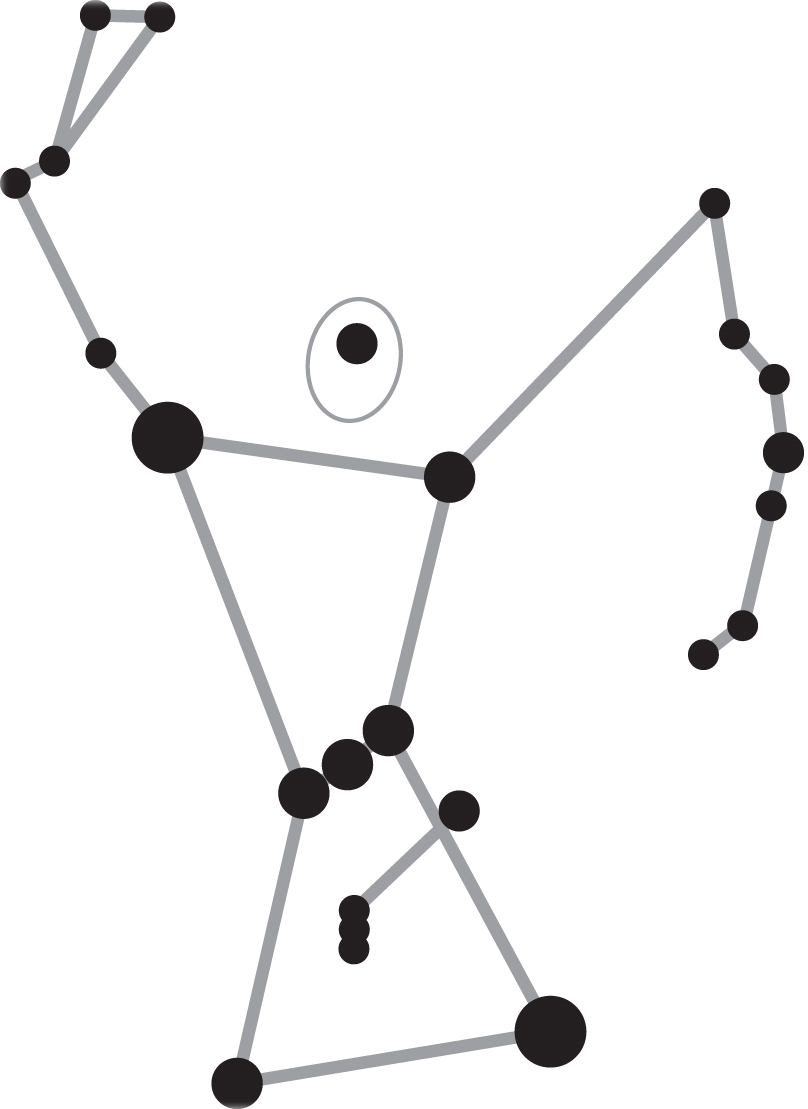

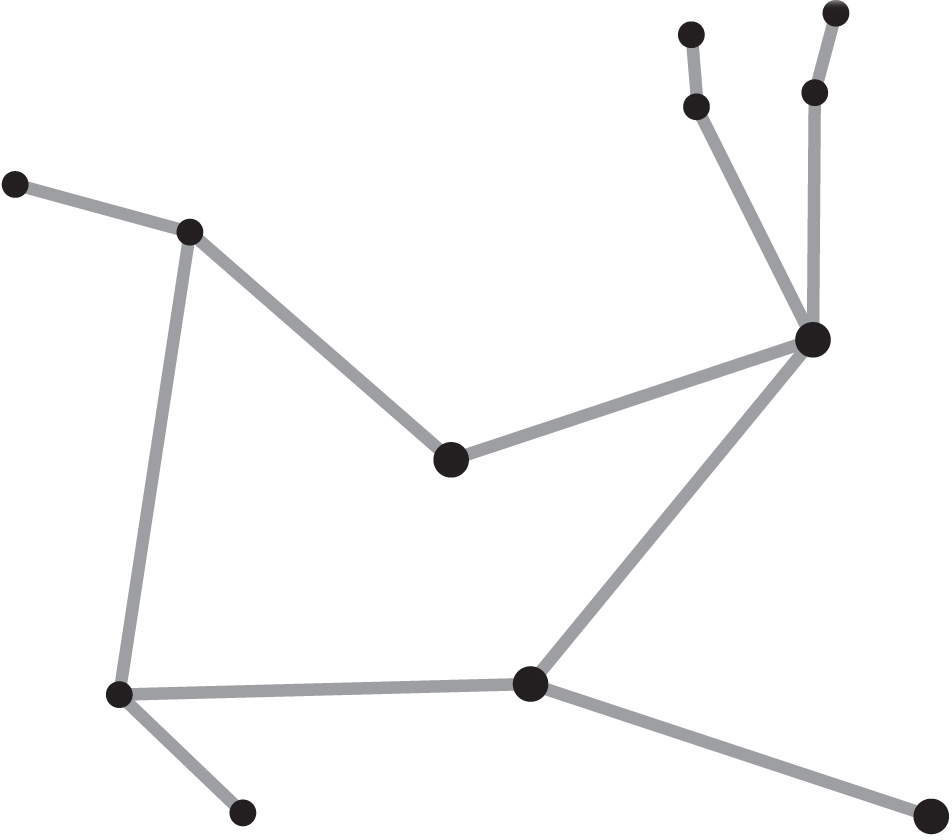

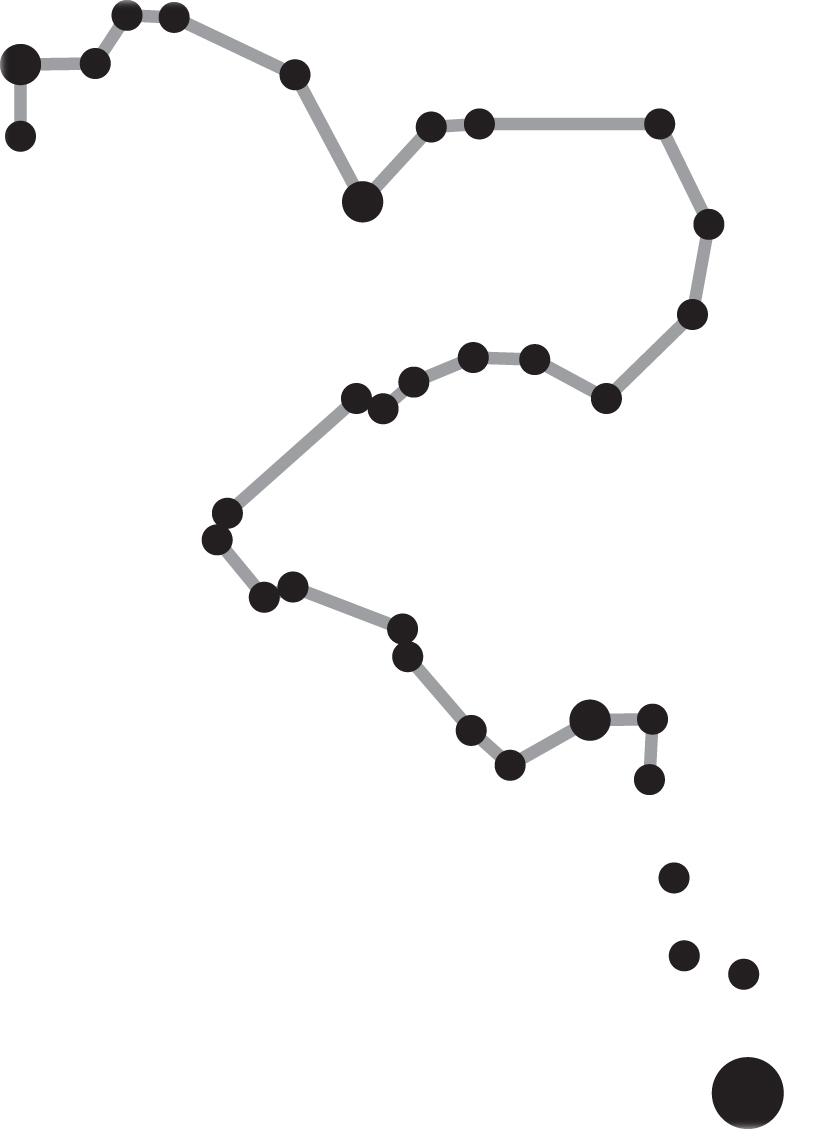

ORION, THE HUNTER

One man, Orion, loomed large and mighty among mortals, but stumbled and fell into the same folly of conceit. In stature he stood like a giant, and his prowess as a hunter impressed all who saw him. Odysseus himself called Orion “the tallest, and far the most handsome” of men. “In his hands he held a club all of bronze” and the pelt of an animal—the trademark of a hunter.1

Orion came of age in the way of the warriors and hunters of Hellas. From childhood, they carry a simple array of weapons into the chase: a club, a pelt, and a knife. Although very young, they sharpen their senses by wandering far and wide, alone, through fields and forests. They learn to detect the slightest movements among the blades of grass or the leaves of trees. They listen for subtle sounds that betray the presence of prey.

As they grow strong and hardy, these hunters of Hellas become brave and bold. Some swagger as if they are brandishing weapons in battle. Their glowing confidence and sharp skills of observation lead them to excel in other areas as well. Their self-discipline and stamina pave the way for success in every endeavor.2

Hunters—young and old—often wander the winding woodland trails with one or more canine companions. The respect between dog and man is mutual, and their firm friendship is often portrayed in hunting scenes painted on pottery. Both play an important part in the chase and share in the feast that follows. Hunters highly value their dogs, especially those of fine form and solid training. They depend on them, not just for stalking hares—the favored game—but for protection from large and lethal predators, such as wolves, boars, bears, and lions.

Like most Hellenes, Orion enjoyed hunting the hares that appear in abundance across the mainland and islands. He thrilled at the quick and lively chase that caused his heart to pound. He savored the succulent meat and valued the plush pelts that are sewn together for warm cloaks and bedding.

In the way of the woodsman, Orion carried the pelt of a large animal to ensnare the hare while his club came hurtling down. In his belt dangled a dagger for skinning and dressing the game. After he roasted the meat on a spit, he used the knife to slice a portion to place on the burning coals as an offering to the gods. Only then did he stuff his ravenous mouth and toss a piece of meat beneath the pleading eyes of the hungry hound.

Rarely did Orion miss a chance to follow his dog in pursuit of prey. The canine would wander warily ahead—quick of eye and keen of scent, with paws toughened by years of roaming in rugged terrain. He was not solid in color, but spotted—a sure sign of good breeding. His hind legs stood long and strong, with plenty of spring for leaping, and perfectly formed for the sprint.3

On the trail, the hound trusted his sharpened sense of smell and followed his nose while sniffing the earth for a sign. For this, Orion favored a crisp morning in spring or fall—not in winter, when the frozen ground conceals the scent of prey; nor in summer, when heat disperses the smell from the sunbaked soil. Nor did the hunter delay until after dawn, when the scent of the previous night grows faint, and the rising wind of daytime whisks it away.

As they wandered the woods together, with the dog silently searching for the scent, Orion whispered a prayer for success—a pledge of first portions of meat for Apollo and Artemis, the twin gods of the hunt. Suddenly the dog trembled and shook in his tracks upon detecting a tempting smell. The hare, somewhere nearby, remained silent and still as a statue. To hide himself in a half-dug hollow or clump of grass, his head and body lay prostrate, with legs tucked underneath. His long ears lay flat on his back.

With a frenzied yelp, the dog shot along the line of scent, swerving to and fro like an un-fletched arrow. He followed close on the course while “barking freely” and running “fast and brilliant in the chase.” At the last possible moment, the hare bolted and fled, with ears held high. Twisting and turning—teasing his tracker—he darted down shortcuts known only to him. He ran the poor dog through brambles and briars, then up—always up—steep slopes.

The cunning hare knew from experience to “cross brooks and double back, and slip into gullies or holes.” More often than not, he outsmarted the hound. But Orion and the dog never seemed to mind. Tomorrow’s dawn always brought another delightful chase.4

Nothing in heaven or earth could ever distract Orion from his love of the hunt, until the day he laid his eyes on the Pleiades. The darling girls—the seven daughters of Atlas and Pleione—had attracted many men, but none more deeply smitten than him. Like a woodsman after a wary deer, he pursued them with an obsession—but all in vain.

Before now, no maiden had escaped his affections. Some say even Artemis—the champion of chastity—almost fell for his manly charms. But the apprehensive Pleiades resisted his every impassioned ploy.

At last, the beleaguered sisters begged Zeus for protection. The god of sky and storm obliged, and changed them into a peaceful covey of pleasantly cooing doves. In later years, he granted them immortality among the stars, where they rest forever—nestled together in lovely company.5

Orion reeled at the rebuff. Deeply disappointed, he wandered back to the woods to follow his first love—the hunt. Now his pursuit of game became more excessive as he tried to bury his feelings for the Pleiades behind a show of bravado.

Loudly, Orion boasted that he could vanquish any beast—great or small. Gaea—Mother Earth—finally heard enough. She abhorred his blasphemous bellows against nature, and shuddered in fear that he might come near to destroying all the fauna she dearly loved.

So Gaea, who once sent the monstrous Typhon against the gods, summoned a Scorpion, colossal and cruel, to slay Orion. Like Aesop’s cocky rooster, Orion crowed too loud and lured a predator upon himself.6 The mighty hunter now became the prey.

Orion |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Orion |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Rigel |

05h 14m 32s |

−08° 12′ 06″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

While Orion walked in the woods one day, the Scorpion—born of the earth—burst to the surface, showering dirt in every direction. On spying Orion, he bore down hard and fast, scurrying swiftly forward on eight arachnid legs, with pinchers snapping. Orion raised his thundering club and fended off the claws with lightning strokes. But soon the Scorpion brought his stinger into play.

The stinger stretched longer than Orion’s club and dripped with poison more potent than the venom from a hundred vipers. Dodging the deadly dart, the embattled man struggled to reach the monster’s head and crush it with a single savage blow of the club. As Orion pushed desperately forward, with eyes wide and watching in every direction but down, he tripped on a boulder and tumbled to the ground. In an instant, the Scorpion shuffled forth and pierced him through the heart. Thus, the mighty hunter fell to the “fiery sting” of a scorpion “proving mightier.”7

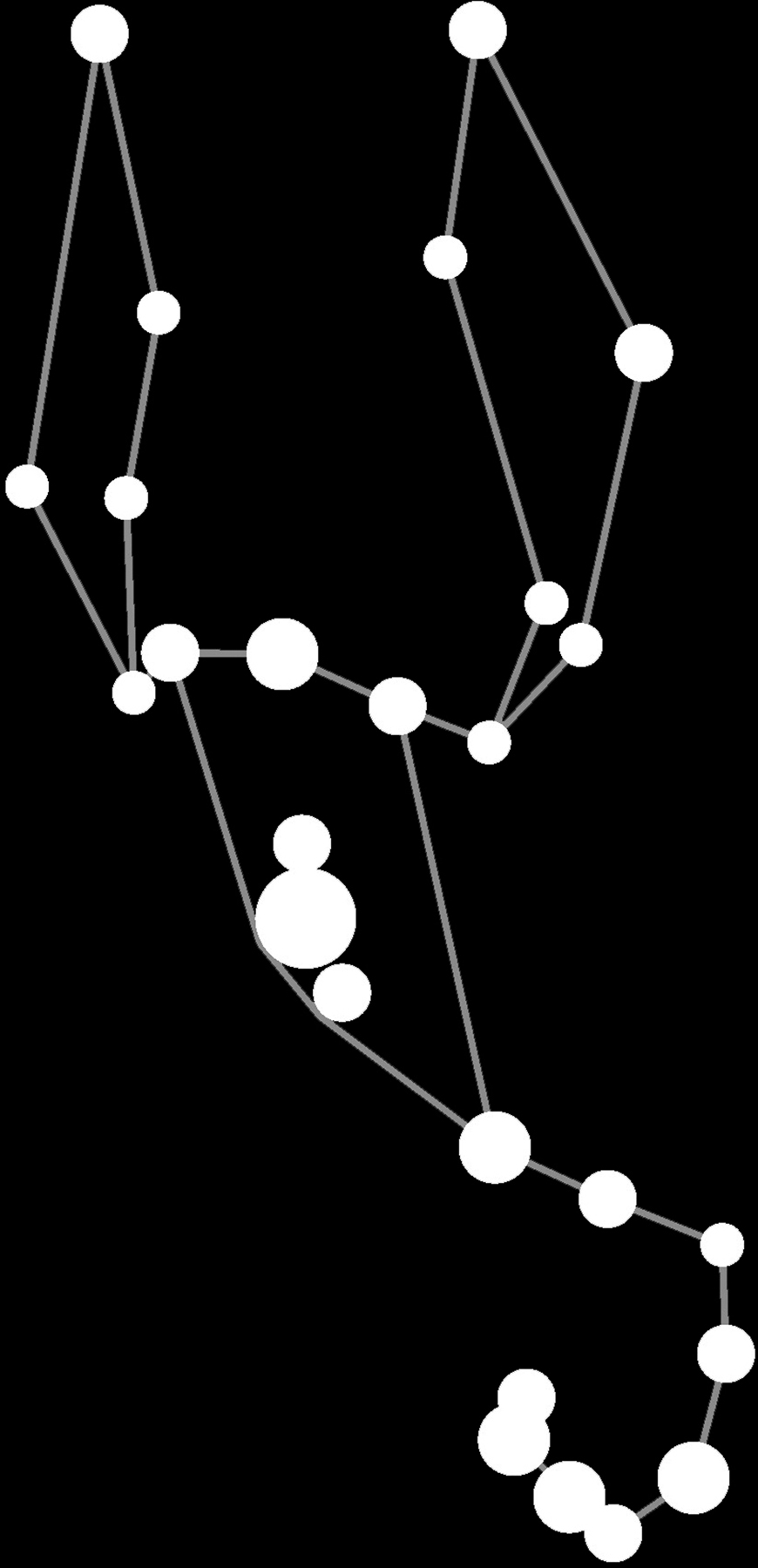

When ORION died, Artemis fell to her knees and grieved. She pleaded that the hunter might receive a home in heaven. Zeus complied. But because he despised immoderate pride in mortals, he placed the SCORPION in the cosmos as well. There, the beast forever follows Orion and offers a lesson for all who see—to avoid conceit for fear of a fall.

The massive Scorpion stretches so far across the celestial sphere that he occupies more than his fair share of the starry sky. To remedy this, his powerful pinchers became defined as a separate constellation, called the CLAWS.8 As the Scorpion appears on the eastern horizon, Orion seeks shelter far to the west. But when the Scorpion is hidden from sight, Orion seems happy in his heavenly home, and no one shall ever “see other stars more fair.”9 With his enormous stature and radiant aura, as well as his position among the equatorial stars, he shines down upon all the people and places of the Earth.

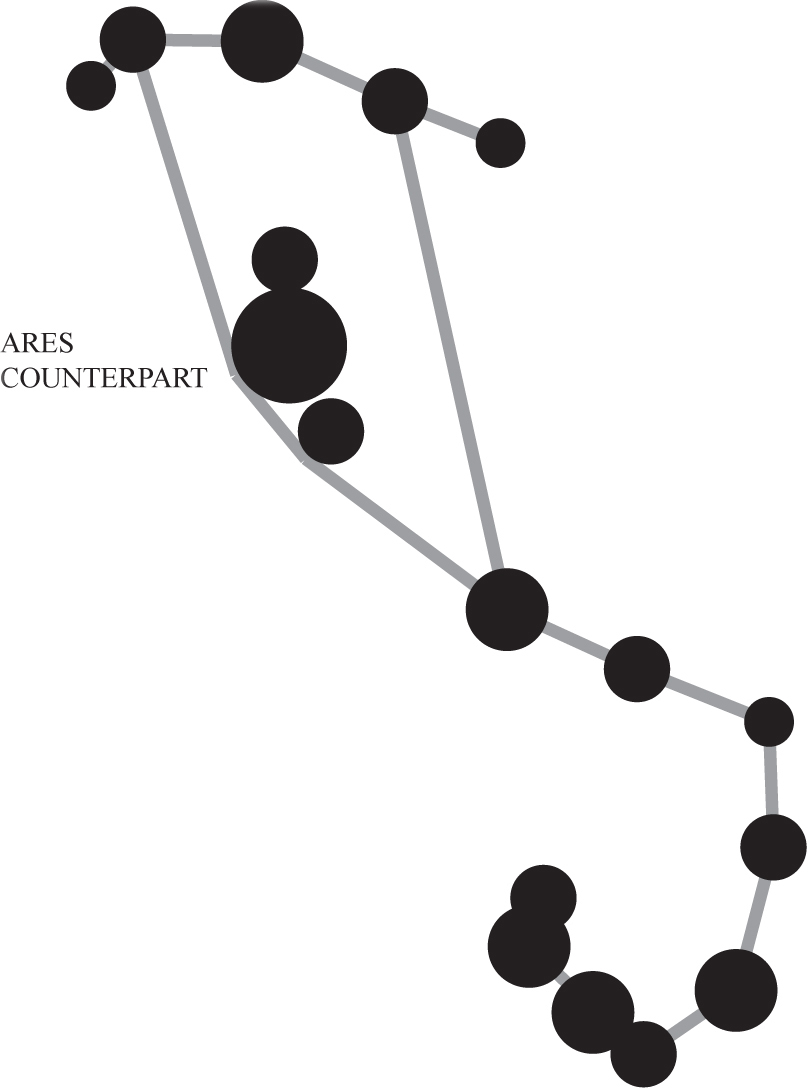

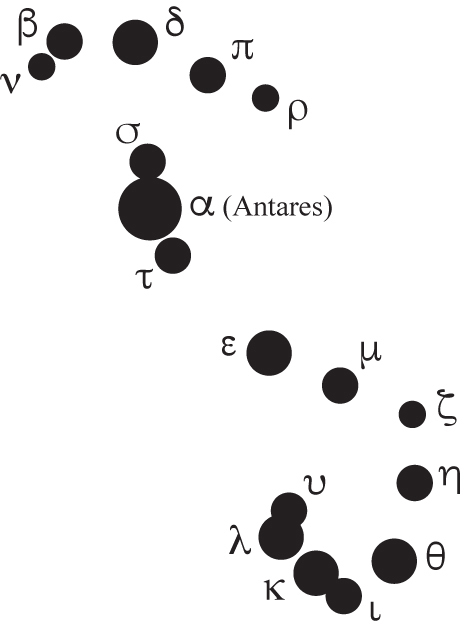

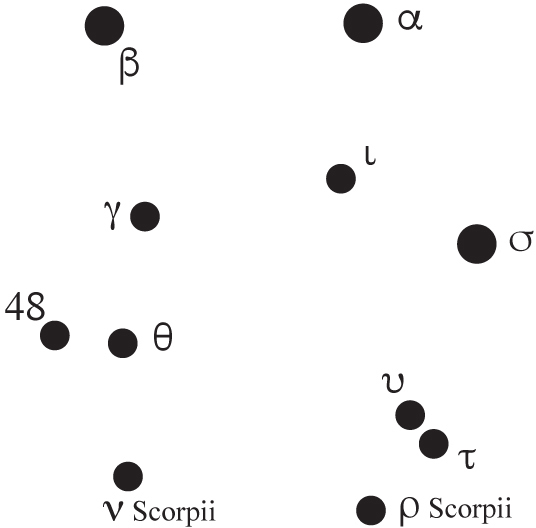

Scorpion |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Scorpius |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Antares |

16h 29m 24s |

−26° 25′ 55″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Claws |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Libra |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

β Librae |

15h 17m 00s |

−09° 22′ 58″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

From on high, Orion still pursues the Pleiades across the sky.10 And yet, he prefers to hunt the celestial prey—with a pelt in the left hand, a club held high in the right, and a glittering knife tucked into his belt. Even the Bear “circles ever in its place and watches Orion” with suspicion.11 But the hunter’s attention is fixed on the HARE, who races ever underfoot, with ears erect.

Here, Hermes—the messenger god—set the Hare to honor his awesome agility and speed. Like his earthly counterparts, the Hare sits silent and still among the stars, ready to run when discovered. Then he darts away, managing to stay just beyond reach, as though he enjoys the hunt as much as does the hunter.12

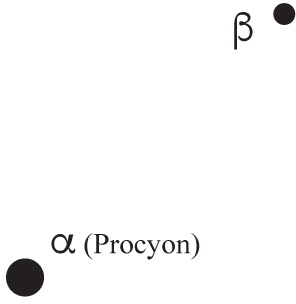

Orion’s spotted comrade—the DOG—also joins the chase. Bounding through the astral lights, he bursts forward on long legs toward his prey and stays close on the heels of the cunning Hare. Like Orion, the Dog’s constellation burns brilliant in the night. On his muzzle he bears the brightest star in all the sky—the DOG STAR, that some call Sirius.13

Hare |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Lepus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

α Leporis |

05h 32m 44s |

−17° 49′ 20″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Alongside the Dog frolics a playful pup—the smaller dog of Orion. The puppy’s constellation is named HERALD OF THE DOG, because he rises above the horizon before the larger canine comes to view. The little dog likes to join the hunt, with his tiny tail happily wagging. But lacking the steady self-control of the older hound, he sometimes jumps ahead and spoils the stalk, or straggles behind and pauses to nip at flowers, as playful puppies will do. On his muzzle he carries a single star. On his flank glimmers a far more luminous light called HERALD OF THE DOG STAR, or Procyon. This star shines only slightly less bright than Sirius.14

Dog |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Canis Major |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Sirius |

06h 45m 09s |

−16° 42′ 58″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Herald of the Dog |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Canis Minor |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Procyon |

07h 39m 18s |

+05° 13′ 30″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

THE FALL OF PHAETHON

High in heaven, Orion and his dogs hunt at the mouth of the “deep eddying” River Eridanus. The sad River—now a stream of stars—recalls the tragic fall of Phaethon, who, like Orion, was punished for his pride. Phaethon’s father reigned on high as Phoebus Apollo (Bright Apollo)—the shining god of the sun.15 But the boy was born a mortal child, raised by a caring mother—Clymene—and his older sisters, the lighthearted Heliades.

The sunny sisters loved to play among the trees on the riverbank, spreading their arms and fingers wide like the branches above or adorning their hair with the colorful autumn leaves. Sometimes they mimicked the cheerful songs of birds that flitted from twig to twig.

Phaethon joined their happy outings, and often paused with the girls to watch the wondrous sun as it rose and fell in the sky. First, it dispersed the darkness of early morning. Then it followed a golden arch over land and sea, across the broad, blue expanse. The children knew to be back home by the time it arrived on the western horizon.

From the beginning, Clymene told her children the truth: that the shining sun was indeed their father, Phoebus Apollo. She assured them that he smiled down on them daily and tanned their faces and gave their cheeks a rosy glow. Phaethon longed to be like his glorious father, but alas, he found himself forever bound to earth.

As the years passed and the restless boy grew bolder, he assumed the visage of invincible youth. With childhood fears left far behind, he decided to face his father at last. Straightaway he packed a bundle, slung it over his shoulder, and marched for many weary days to the base of Mount Olympus. Undismayed by the lofty peaks that jutted above, he began to climb, slowly and steadily, toward the top.

Upon surmounting the shining summit, he promptly found Apollo’s resplendent palace. Without delay the brash boy pushed the gates wide open and entered. Soon he stood in the sun god’s beaming presence.

Apollo welcomed Phaethon warmly, as a father to a son, and promised to hand him his heart’s desire. The boy had no need to ponder his response. At once, he declared his undying wish, his lifelong desire: to drive the chariot of the sun for a day. From there he hoped to behold all the world on high, from earth to sea to sky.

Aghast at the reckless request, Apollo tried to dissuade him. None but himself, he said, could manage the fierce and fiery team of horses that draws the chariot across the cosmos. Not even Zeus would dare to take on the task.

The climb up to heaven was far too steep, Apollo warned, and the descent even more dizzying and dreadful. In addition, dangers dwelt among the stars. The Scorpion, the Crab, the Lion, and the Bull glowered at the deity’s daily intrusion. How quickly they would maim a mortal youth—stinging, pinching, clawing, and goring!

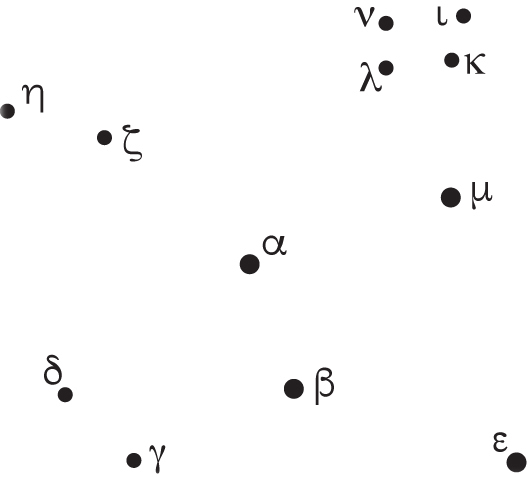

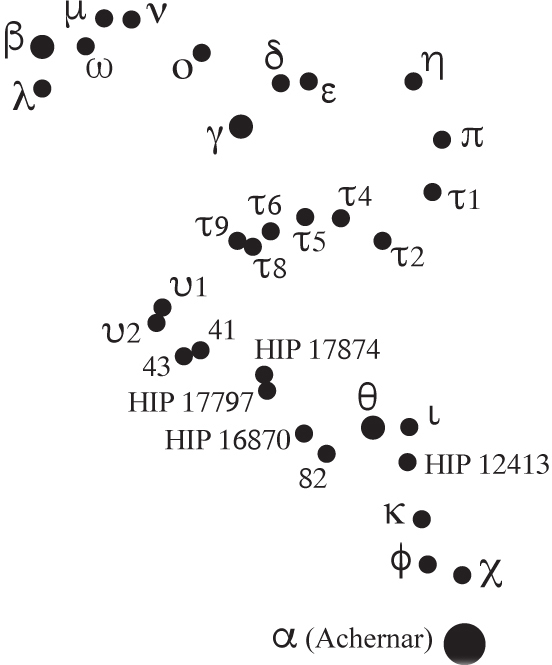

River |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Eridanus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Achernar |

01h 37m 43s |

–57° 14′ 12″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Phaethon only smiled at Apollo’s words of warning, and the sun god saw for himself the folly of trying to withdraw his promise. Bowing his head and shaking it slowly, he whisked his son away to the sunlit stable in the east. There he prepared the blazing chariot and team of spirited steeds. Then he returned to his throne, sullen and troubled, to watch, with deep foreboding, the fateful day unfold.

Dauntless as ever, Phaethon leapt into the chariot and grabbed the reigns as if right at home. In an instant, the chariot jolted forward and shot into the air like an arrow, climbing at an alarming rate. Soon the team parted the puffy clouds and hurtled high into the blue sky. Fear gripped Phaethon now, and he ventured an anxious glance below. He watched aghast, in great distress, as homes, towns, islands, and mountains dimmed and finally disappeared in the distance.

As Phaethon began to shake with fear, the stormy horses detected the driver’s lack of control. Flushed in frenzy, they seized command and fought and jostled among themselves for a new path to follow. Without warning, they wheeled in every direction.

Into the highest heaven they flew, disrupting the peaceful abode of the stars. From there, they streaked toward earth in fiery descent and slammed across the mountaintops, leaving them leaping in flames. The lofty peaks—the sacred pinnacles of the gods—now burned and billowed in ruin. Even Olympus began to blaze. Forests followed—engulfed in violent infernos—and the waters of many rivers boiled away into suffocating steam.

Flora withered and died. Fauna scattered and fled; and humans wailed aloud as their homelands blackened in ashes. Gaea screamed for action from the immortal gods, demanding they save her lovely earth and all its living beings. Suddenly, Zeus stepped forward, furious at the widespread destruction and the chaotic disruption of his peaceful skies. He seethed, too, at the conceit of a brazen youth, who dared to assume the role of a god.

With a single stroke of his thunderbolt, he felled the tempestuous team of horses, and struck the rider and chariot from the sky. Phaethon, with “fire ravaging his ruddy hair,” tumbled through the air with the burning wreckage—“as sometimes a star from the clear heavens . . . seems to fall.” Into the River Eridanus he shot like a flash. With a deafening splash, he caused the waters to hiss and steam.

The naiads of the river sullenly retrieved his burned and broken body. Then they reverently buried the boy, “still smoking with the flames of that forked bolt.” At last, in great solemnity the river nymphs engraved his epitaph: “Here Phaethon lies: In Phoebus’ car he fared, and though he greatly failed, more greatly dared.”16

Phaethon’s inconsolable sisters, the Heliades, gathered close around him. There they mourned for their brother so steadfastly—without stirring from the spot—that they took root on the riverbank and assumed the form of poplars. With quaking leaves they shed sweet tears of amber that showered down upon the rippling waters and soft grass below. Zeus tried to assuage the sorrow of Phoebus Apollo by assigning the RIVER a place in the sky in memory of his children. Now a stream of stars stands in place of the once proud flow of water known as “Eridanus, river of many tears.”17

BELLEROPHON, THE PROUD

Another young and haughty hero—Bellerophon—suffered a similar fate. None could deny that he had performed amazing deeds. First, he found and approached the wild and unruly winged horse, Pegasus. Soon after, he softened the stallion’s rampaging heart with his gentle hand and soothing voice. Then he cautiously climbed on his back and rode the steed until they became like one in flight.

Now the hero and horse flew far and wide to find adventure. In the east, they engaged in battle with the she-warrior Amazons—who despised all men and even discarded their own infant sons. In the furious fight that ensued, Bellerophon vanquished many of the warlike women. Flushed with victory, he now pursued the deadliest demon of all. Leaping proudly on Pegasus’ back, he flew aloft toward the menacing mountains to face the dreaded Chimaera.

The Chimaera—the odious daughter of Typhon—made her lair among the desolate heights and rocky crags. Only through the air could the horse and rider find her. Huge and hideous, her body was that of an agile mountain goat that allowed her to leap from peak to peak. She had the flesh-eating head of a lion and a tail that coiled and writhed like a snake, striking with venomous fangs. At night, the cruel beast incessantly stalked the valleys, “breathing out, terribly, the force of blazing fire.”18 She hated every living thing, but, most of all, abhorred the sight of humans.

As soon as she spied the horse and rider hovering above, she roared forth a wrathful flame that singed their hair and baked their skin. The two bellowed in pain but continued their pursuit. Circling at a distance, they dodged the fire and fangs while the young man pierced the creature’s body with a rain of arrows. At last, she grew faint and plummeted to her fate in the valley below.

Now that Bellerophon had laid low the fierce Chimaera, he assumed himself invincible, with victory even over death. He began to imagine that he, who seemed immortal, must surely deserve a divine home. Climbing once more on Pegasus’ back, he goaded the horse to soar through the sky, toward the summit of Mount Olympus. Here he expected to join an applauding pantheon of gods.19

As Bellerophon spurred his winged horse higher and higher above the clouds, Zeus delivered a woeful welcome—a gadfly—to render a painful bite on Pegasus’ back. The horse began to buck wildly, dislodging Bellerophon and causing him to fall through the blue sky and down to the dusty earth. A thorn bush saved the tarnished hero from sudden death, but left him battered and bruised in both body and mind. Despised by the gods, and lacking his former strength and self-esteem, he wandered alone until his final days, “eating his heart out, and shunning the paths of men.”20

In spite of all his amazing achievements, his fatal flaw—his arrogance—doomed him in the end. Once again, the deities delivered the stern warning, in no uncertain terms, that pride precedes a fall.