Orion stood tall with the stature and strength of a hero. Phaethon ventured forth with the confident glow of youth. Bellerophon vanquished dark forces in desperate battle. But the three fell victim to the same invisible foe: their own arrogance. They plummeted to their doom as punishment for pride, as a mighty oak crashes to the forest floor.

They were not alone. Mortal women succumbed to the same vices as men. You have heard of Medusa—a monster so ghastly that those who looked upon her froze into cold, lifeless stone. But the wretched creature was once a young lady of radiant beauty. Her lovely form, her flowing hair and enchanting eyes shone like a goddess and captured the gaze of men and women, of birds and beasts, of flowers and trees, and of immortal beings.

Even Poseidon—god of the sea—could not resist her charms. From the salty surf he daily splashed ashore and, at a distance, followed her footsteps. Her allure captured his heart and conquered his mind until he yearned for nothing more. Desperately, madly, he became entranced by the maiden Medusa.

But the admiration of deities and men destroyed her. Her sweet smile slowly sank and became a haughty sneer. At last, her pride proved so loathsome to the gods that Athena, who was also quite jealous, transformed Medusa into a gruesome ghoul. Her fair form now slithered on the ground like a serpent. Her flowing hair writhed as a tangle of poisonous snakes. Her enchanting eyes destroyed all who beheld her, so that she never again looked upon joyful life without watching it decay into dreadful death.

In her new form, hatred consumed Medusa, poisoning her heart and blackening her blood. Day and night, she shouted bitter blasphemies at the gods, but remained helpless to harm them. Instead, in hateful agony, she determined to destroy as many mortals as wandered within her dreary domain.

PERSEUS AND ANDROMEDA

At last, a trembling handful of heartbroken survivors came forward, forlorn, with heads held low in fear and sorrow. They had lost their loved ones—forever frozen in stone and condemned to stand as silent ornaments of anguish in Medusa’s miserable lair. In despair, the survivors pleaded for the help of Perseus, a hero among them who shone with the unbounded boldness of youth. Together, they begged him to stalk and destroy the fiend. Perseus, the son of Zeus and Danae, stepped forth without further thought, as heroes will do. In haste, he pursued the dangerous quest and tracked Medusa to her haunts. Drawing near, he cautiously stalked past pillar after pillar of stone-cold mortals who had all shared the same misfortune.

To avoid a similar fate, Perseus wielded an assortment of weapons that had been given to him by the gods. A polished shield let him see Medusa’s horrid reflection rather than face to face. Small wings attached to his feet launched him fast in flight, and a magic helmet rendered him invisible to her sight. Upon reaching the lair, he took to the air and searched with keen eyes until he spied her from above.

Then, like a storm, he burst upon Medusa with a lightning-fast sword. The monster swiftly spun toward the sound of the rushing wind. But before she could fix her eyes on him, Perseus, with a single slash, severed her scaly neck. The head thudded heavily to the ground, with glowering eyes still open and serpent hair writhing and snapping. Ever so carefully, he covered the lethal eyes and retrieved the head. In disgust, he dropped the loathsome trophy into a leather bag and made his winged departure through the air, far over the sparkling sea.

As the lifeblood flowed from Medusa’s head, droplets from the blood-soaked bag fell and mingled with the seafoam far below. Poseidon mourned aloud and lamented the maiden’s brutal punishment and cruel destruction. Unable to undo the dictates of fate, he decreed instead that Medusa’s blood should join with his own seafoam to beget a beautiful being. For now that Perseus had released Medusa from her wretched existence, the god of the sea wished something good to come from the once-radiant woman he had loved. According to Poseidon’s will, Pegasus—the winged horse, white as snow from muzzle to tail—was born of the blood and foam, and sprang from the salty sea.1

Meanwhile Perseus, rising in triumph on winged feet, soared for days and nights through the heavens, with the white-capped sea below and the approving gaze of the starry Pleiades above.2 From his vantage point he beheld many strange and exotic kingdoms. In the far west he alighted in the land of the giant Atlas, whose wife, Hesperis, and daughters, the Hesperides, graced that tropical clime.

Perseus and the family fell into pleasant conversation. But alas, poor Atlas, more brawn than brain, spied the forbidden, blood-soaked bag. In an unguarded moment, with one curious peek at the hideous head and lethal eyes of Medusa, he froze into the North African mountain range that forever bears his name. With profuse apologies to Hesperis and her daughters, Perseus resumed his flight through the stars for three more days and nights. “Thrice did he see the cold Bears” in the northern sky, “and thrice the crab’s spreading claws” among the constellations.3

On the fourth day, while following his course above the shoreline of Joppa, a tiny object, far below, captured his attention. Circling downward for closer inspection, he discovered a maiden, all alone, chained to the jagged rocks that jut from the surging sea. Her delicate form stood fully exposed to the salty air and rising tide. In rapid descent, Perseus rushed to her side.

The silent girl, cold and lifeless, seemed beautiful beyond perfection—the masterpiece, perhaps, of a sculptor inspired by the gods. But then “a light breeze . . . stirred her locks and warm tears welled in her eyes.”4 The maiden, Andromeda, refreshed by the ocean air, shortly regained her senses. Startled at first by the stranger beside her, she soon set fear and shyness aside and told the young man her woeful tale.

Much like Medusa, her mother Cassiopeia had boasted of her own flawless beauty. Cassiopeia—too foolish to realize how foolish she was—even claimed to outshine the Nereids, the lovely sea nymphs cherished by Poseidon.5 The god of the sea seethed at the insult, but Cassiopeia remained self-absorbed and ignored his vengeful wrath. She failed to consider that it was Poseidon who punished wayward sailors on the storm-tossed seas, and Poseidon who sent rumbling earthquakes and raging tsunamis to destroy coastal towns and entire fleets of ships.

The indiscretion of Cassiopeia now prompted Poseidon to unleash Cetus—an amphibious Sea Monster, prodigious and deadly. The voracious creature ravaged the land of Joppa, daily devouring unaware fishermen along with their boats and nets. He crunched the bodies and bones of shepherds and flocks as they roamed the rocky coastal paths. In gluttony and greed, he even snatched screaming guards from atop the city walls.

At last, the husband of Cassiopeia—the weak-hearted Cepheus, King of Joppa—saw no choice but to appease Poseidon with a sacrifice of royal blood to the monster Cetus. Soon Cepheus settled on a suitable victim: not himself—that would never do—nor his wife who had caused the whole misfortune; instead, he gave up their gentle, obedient daughter.

When the sobbing girl had finished her tale of impending doom, Perseus looked up, startled to see the barnacle-encrusted beast already “hurrying from the Atlantic water towards its maiden-feast.”6 The hero, smitten with love for Andromeda, promptly prepared for battle. In a flash, he leapt into the sky with winged feet and a gleaming sword in hand.

Suddenly, Cetus broke the surface of the sea. Perseus attacked at once. Time and again, from high and low, from front and back, from side to side and every angle he hacked and stabbed, gouging deep wounds while darting away from the gaping jaws and gnashing teeth. At last the loathsome leviathan began to sway, sluggish from fatigue and loss of blood, and finally collapsed with a deafening splash that nearly engulfed the anxious watchers crowded atop the city wall. The grisly deed now done, Perseus freed the fainting girl.

For many days and nights, the kingdom of Joppa reveled in victory with joyful shouts and jubilation, with festive processions and songs. Andromeda, shy and silent, received a warm welcome amid petals of flowers showered from the city wall. All the while, her mother pouted in the background, bewailing the mistreatment that left her ignored and unattended.

Although adored by her countrymen, Andromeda cared nothing for that, or for anything other than Perseus. The two vowed to leave Joppa behind, and, side by side, begin a new life in the seaside city of Argos. Cepheus and Cassiopeia, red in the face, railed against the thought of their daughter marrying the foreign youth. But Andromeda distrusted the judgment of those who had sacrificed her in order to save themselves. With her mind made up, she took Perseus’ hand in hers.

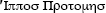

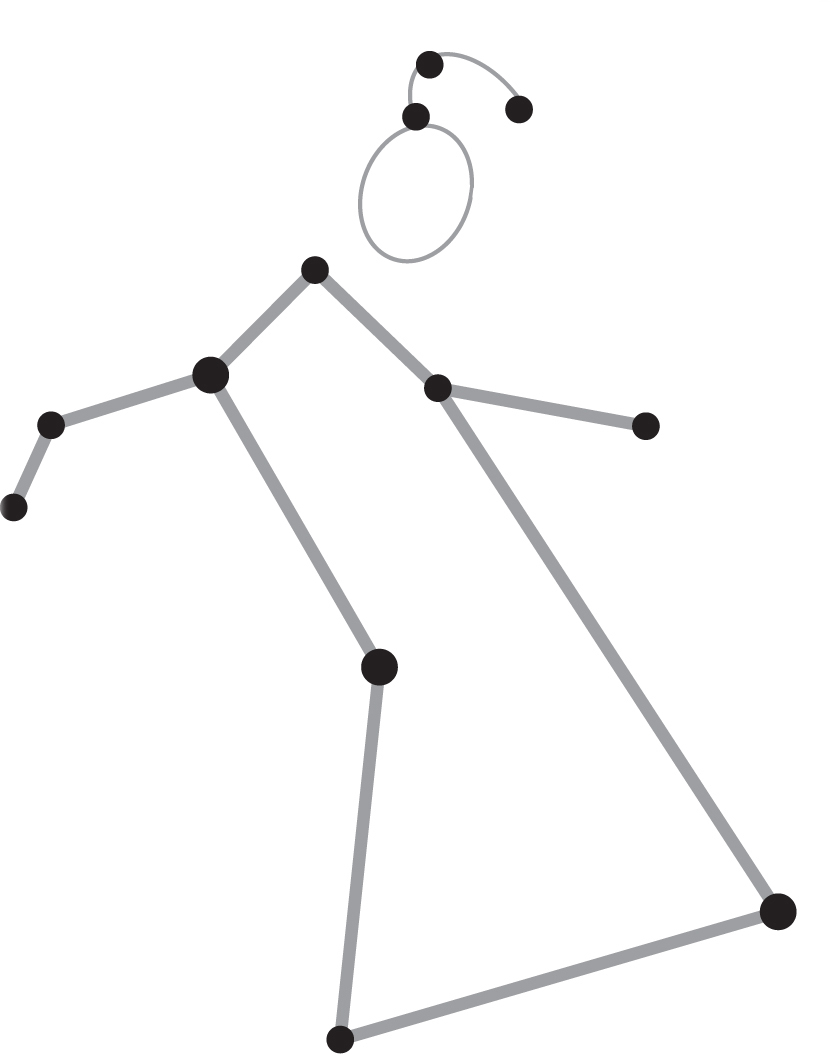

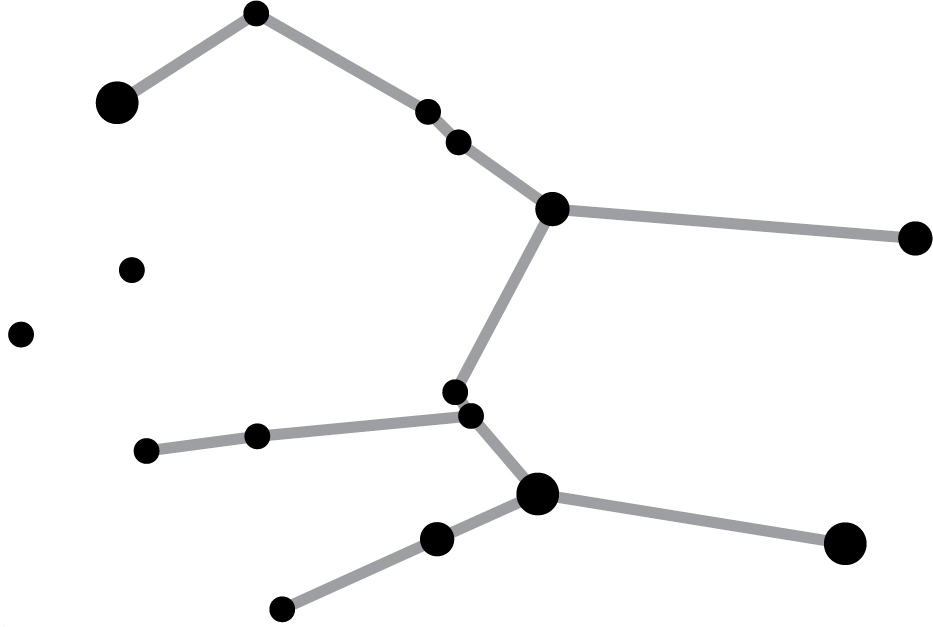

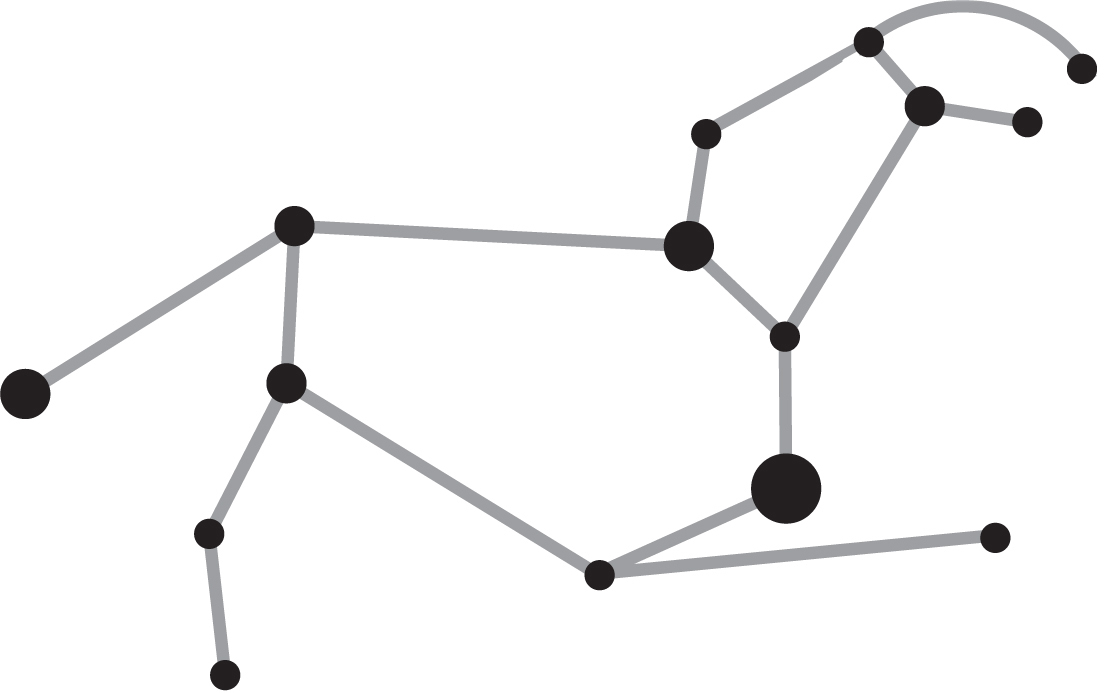

Zeus, the proud father, saw much in PERSEUS that he admired and honored his heroic son in heaven. There, among the stars, Perseus is clad in a sturdy helmet and winged sandals, with a polished shield slung on his back. In his right hand he raises a flaming sword. In the left he carries the ghastly, ghoulish head of Medusa, marked by a beam of light called GORGON. Behind the head trail two stars of writhing serpent hair.7

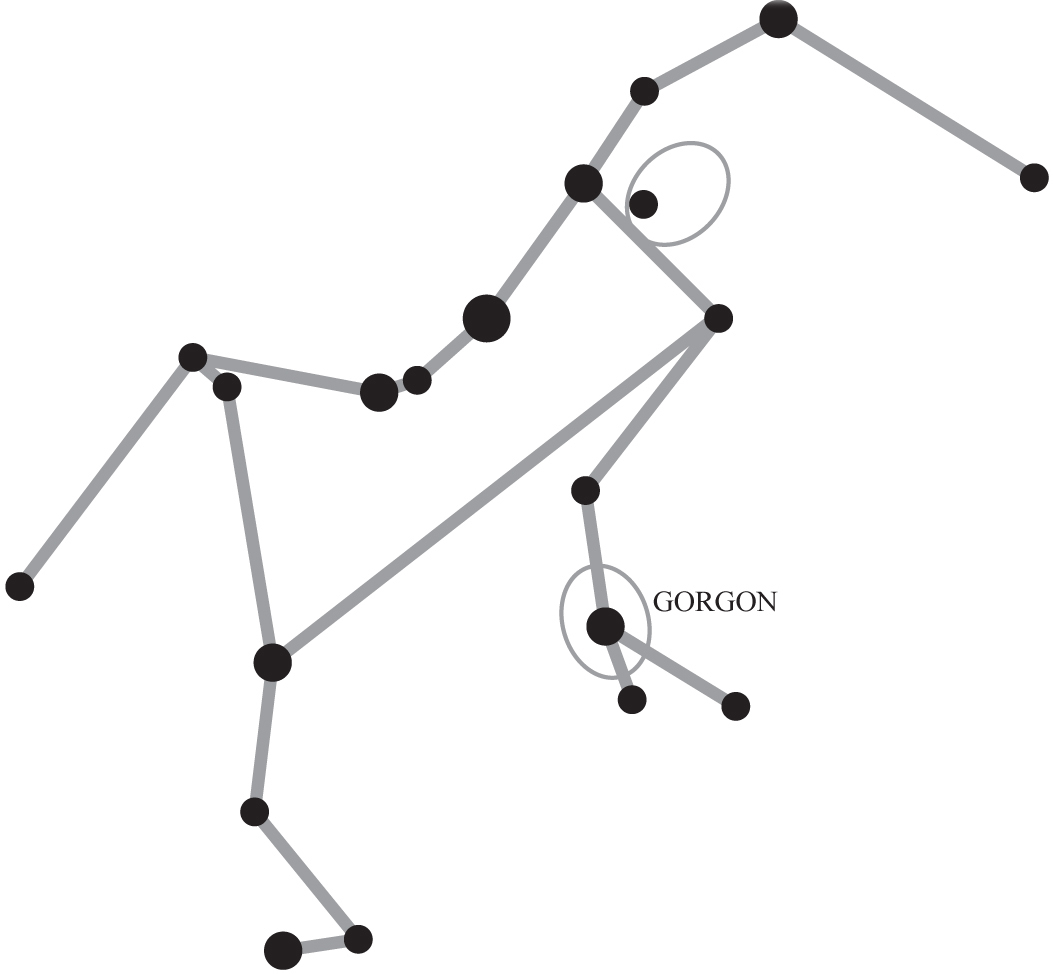

Perseus |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Perseus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Mirfak |

03h 24m 19s |

+49° 51′ 40″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

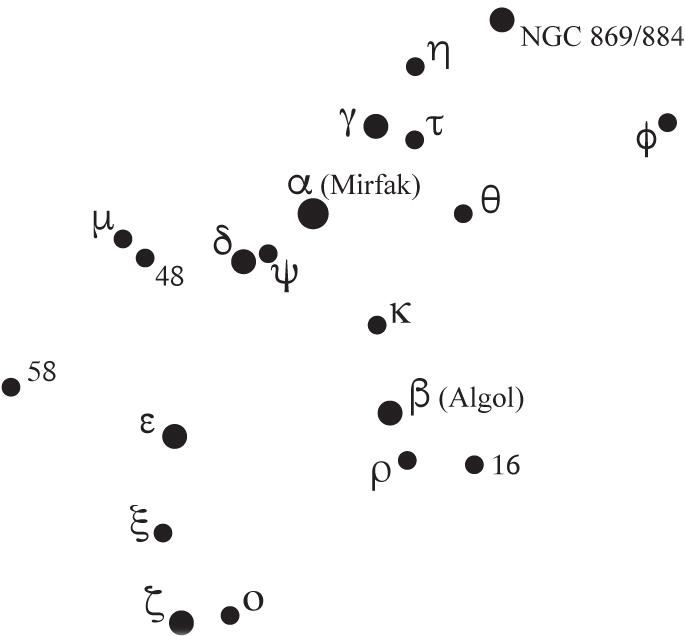

To complete the scene, lovely ANDROMEDA swoons in her chains near the hero’s upraised sword. The SEA MONSTER, with gaping jaws, rises menacingly from the stars beneath her feet, rushing upward, propelled by massive fins. CEPHEUS and CASSIOPEIA are there as well, forever watching the dread event from a cowardly distance.

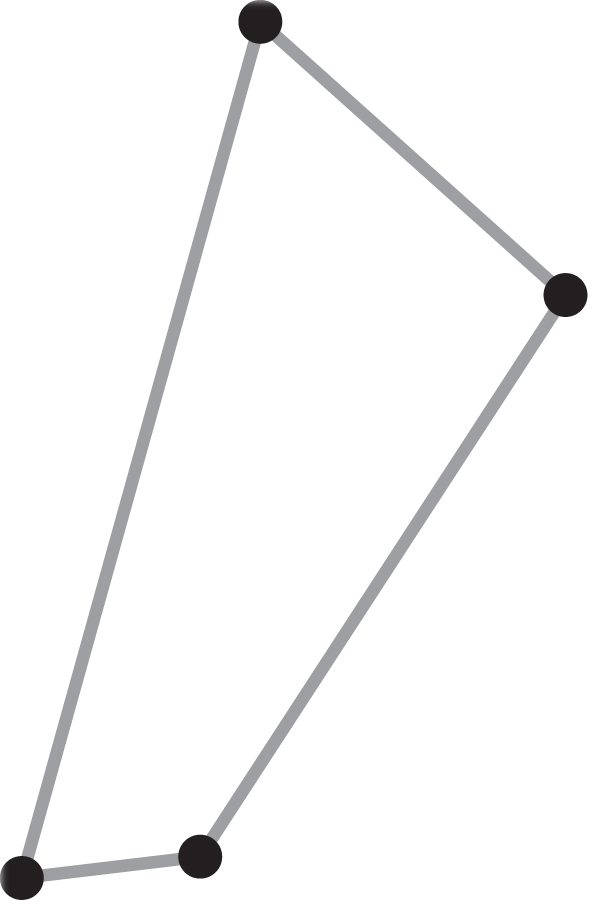

Cepheus wears a felt cap that points forward, in the Asian fashion of his country.8 He recoils in horror at the sight of the approaching fiend. Cassiopeia, saucy and scantily clad, sits on the edge of her throne with arms upraised in suspense. As punishment to the haughty queen, Zeus ordained that her constellation should turn head-downward as she travels across the sky. In this awkward position, Cassiopeia can be neither proud nor modest. For “she headlong plunges like a diver” into the sea, as her stars set in the west.9

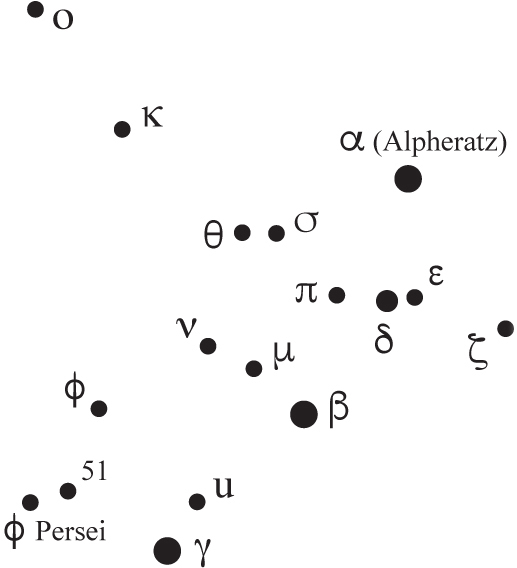

Andromeda |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Andromeda |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Alpheratz |

00h 08m 23s |

+29° 05′ 26″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

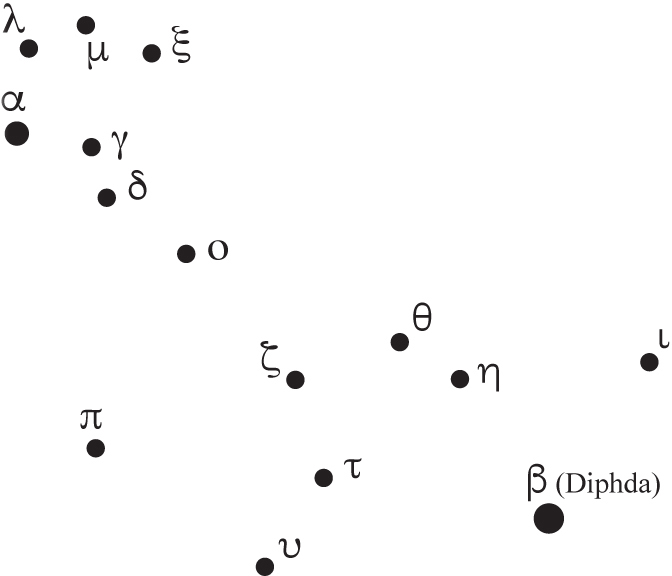

Sea Monster |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Cetus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Diphda |

00h 43m 35s |

–17° 59′ 12″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Cepheus |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Cepheus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

α Cephei |

21h 18m 35s |

+62° 35′ 08″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

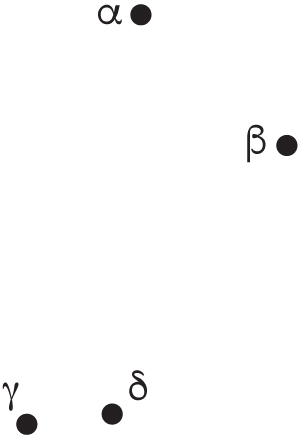

Cassiopeia |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Cassiopeia |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Schedar |

00h 40m 30s |

+56° 32′ 14″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

PEGASUS, THE WINGED HORSE

As for Pegasus, the winged horse that sprang from the sea became famous far and wide for his beauty and bravery. He often hurried to the aid of heroes involved in desperate quests. He carried Bellerophon aloft to vanquish the vicious Chimaera. Then, after Zeus dislodged the presuming youth from his back, Pegasus continued his ascent “and came to the immortals” on Mount Olympus.10 On the shining summit that overlooks the world, he joined the livery of Zeus. Soon he served as the god’s most trusted steed, bearing his flashing thunderbolts throughout the starry heavens.

Horse |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Pegasus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Enif |

21h 44m 11s |

+09° 52′ 30″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

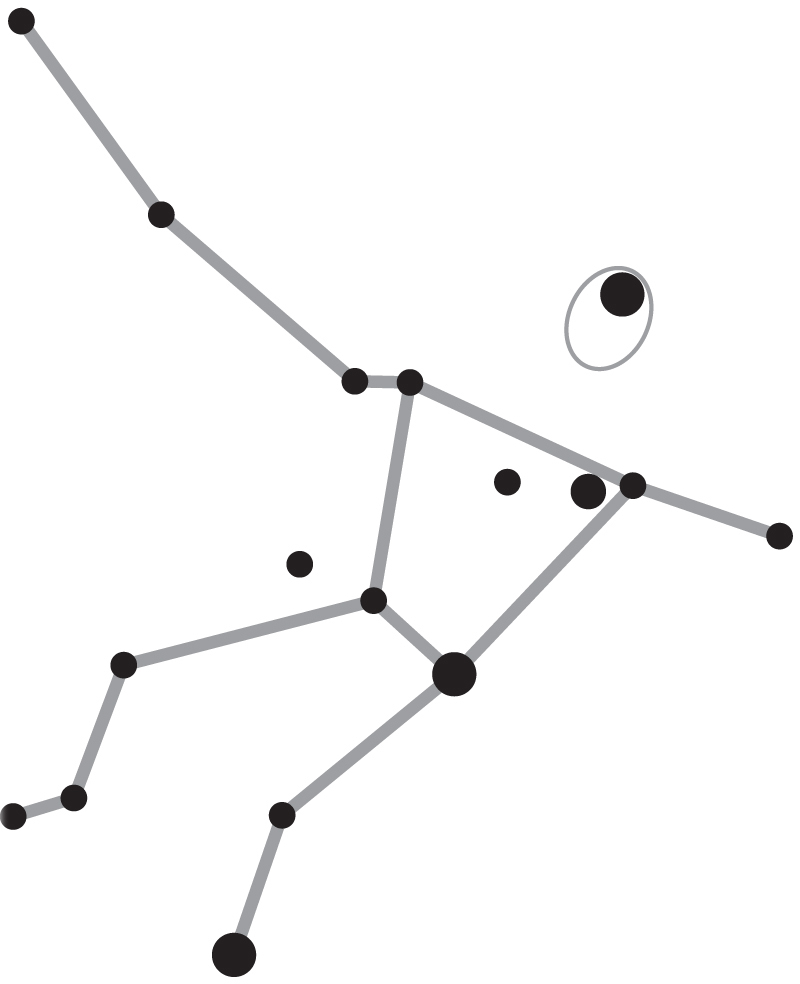

Years later, when the mortal horse died, Zeus provided Pegasus with stars of his own. His constellation, simply called the HORSE, gallops swiftly, with tremendous spirit, through the sky.11 By his side, within easy reach of his muzzle, runs his favorite foal, named Celeris.

During his earthly life, the sleek colt Celeris stood second only to Pegasus in splendor and speed. Celeris also displayed the wondrous traits of his distinguished maternal grandfather, Chiron the centaur.12 Among the stars, only the head of Celeris is visible as he joins his sire in the celestial race. For this reason, his constellation is called the HORSE HEAD.

Horse Head |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Equuleus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

α Equulei |

21h 15m 49s |

+05° 14′ 52″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

THE LABORS OF HERACLES

In Argos, the love between Perseus and Andromeda grew profoundly with the passing years, and they brought many children into the world. Their oldest son, named Perses, became the eponymous ancestor of the Persians. Other sons received renown as forebears of the Mycenaean kings. One of these—Electryon—reigned justly as ruler of Argos. Electryon’s daughter, Princess Alcmene, became Zeus’s lover and bore him a son.

After the birth of the baby, Alcmene soon saw that her little boy—Heracles—was no ordinary child.13 He quickly gained the strength of a grown man, and showed stunning signs of his divine lineage by strangling poisonous serpents and performing other powerful deeds. Upon coming of age, Heracles followed in the heroic footsteps of his great-grandparents, Perseus and Andromeda.

Of all his amazing exploits, Heracles attained greatest fame for accomplishing the Twelve Labors, a series of seemingly impossible feats. The first labor required him to slay the Nemean Lion—a man-killer with a hide no weapon could pierce. The frightened villagers of Nemea had suffered dreadfully, with countless lives lost to the bloodthirsty beast. The brutal lion relished human flesh, but found far greater pleasure in the chase and the kill.

Many valiant warriors had tracked him down only to fall prey to his ripping claws and rending teeth. But Heracles remained undaunted. He had defeated a dozen lions with the help of his heavy club and arrows of bronze. With little trouble and little fear, he found the lair, littered with bones, and emitting a foul and suffocating stench. The lion had no reason to hide his presence. He always welcomed another woeful victim.

As soon as Heracles entered the dreary den, he discerned the huge, shaggy hulk in the darkness and launched a volley of arrows in rapid succession. In dismay, he watched as each bounced off the impenetrable hide and clattered to the cold cavern floor. Furious at the brazen assault, the lion lunged at Heracles with claws poised and fangs bared. As the two interlocked in deadly embrace, the lion slashed and snapped at his assailant time and again. But the powerful man held tight to the mane and slipped his muscular arms around the enormous neck, slowly choking the lion’s life away.

With victory at last, Heracles sat on the ground with a heavy thud and tended to his open wounds. After catching his breath, he skinned the lion with its own sharp claws—the only tool that could sever the heavy hide. From that day on, the lion-skin cloak became the hero’s most treasured possession and trademark.

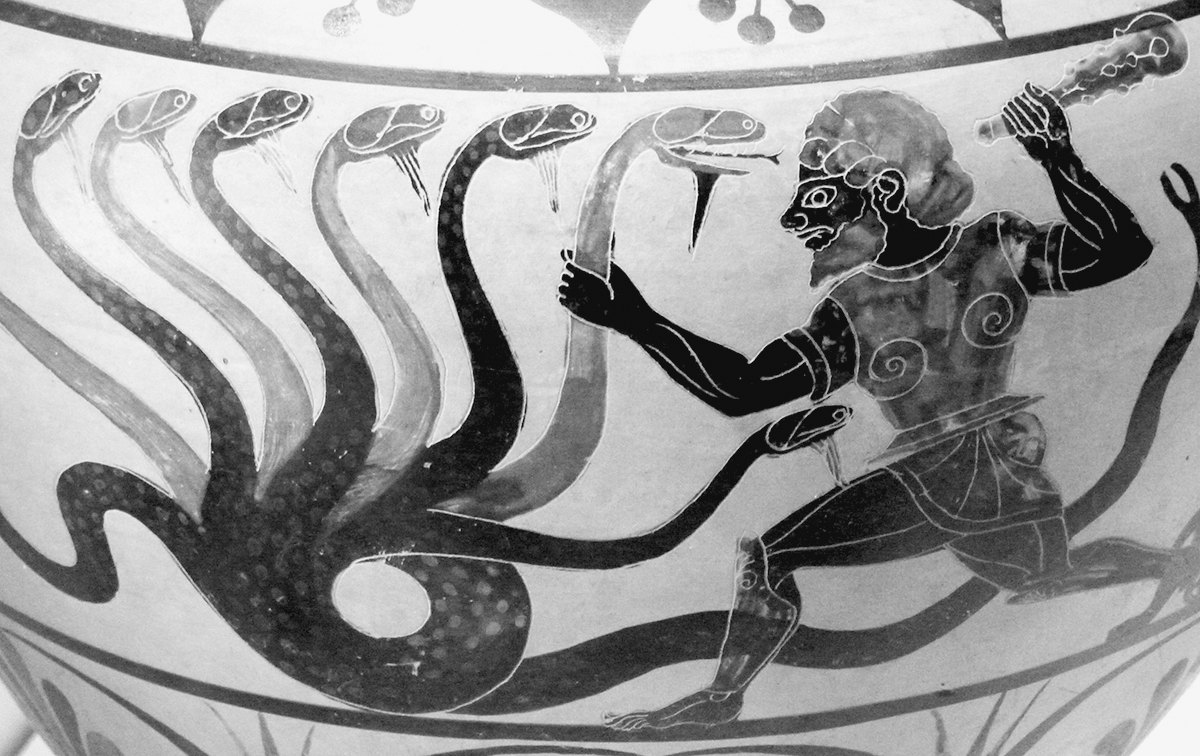

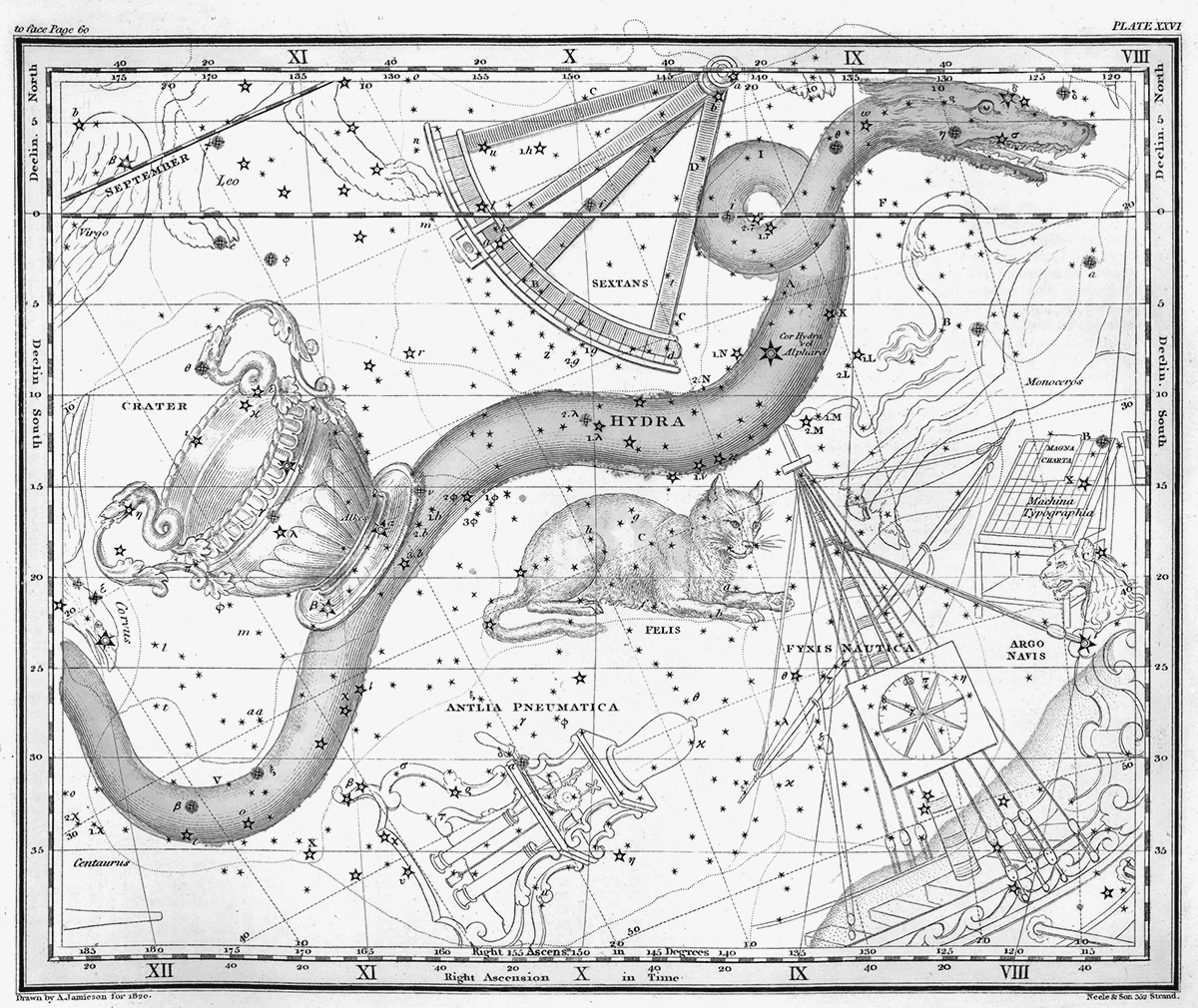

Scarcely had the people of Nemea received the joyful news before Heracles was summoned to an equally trying task. The murky marsh of Lerna, that lay near Argos, had long been haunted by Hydra—the nine-headed swamp serpent, vile and vicious. The monster was one of the ferocious offspring of the “terrible, outrageous, lawless” Typhon—who had once attempted to devour the gods. From deep within her loathsome lair, the Lernaean Hydra slithered in ceaseless search of unwary wanderers.

For most of a day, Heracles struggled through the swamp in stagnant water up to his neck. He held a pine-torch high above his head to light a path through the forbidding fog and gloom. Suddenly he detected a slight ripple on the water. As he inched slowly forward, Hydra burst to the surface behind him. Heracles turned at once and swung his sword, severing one of her snapping heads.

In horror, he watched as two more heads grew promptly in its place. Quickly he lopped off another, but two more emerged. In desperation, he dispatched a third and thrust his torch onto the bleeding wound. The burning neck sizzled and boiled with a terrible stench, then fell with a splash, cauterized and lifeless. Hydra all the while struck with venomous fangs from every direction. But one at a time, Heracles managed to dismember and singe each neck.

When only three heads remained, Hydra’s companion, the Crab, sidled through the mire unseen. With piercing pincers he tore a nasty gash in the hero’s foot. Heracles shouted in pain as he brought the wounded limb crashing down to shatter the shell of the Crab. He then turned his full fury on Hydra, and soon reduced the foe to one immortal head, which could not be killed. This he dispatched and concealed under a massive boulder, where it remains to this day.14

As news of Heracles’ prowess spread through the land, he received frantic calls to more dangerous missions. Among these was his fight with the foul, flesh-eating Stymphalian birds. The menacing, man-eating flock had descended on the people of the Peloponnesus like a dark and ominous cloud.

Day after day, the grim, ravenous birds gorged on men, women, and children, until none dared to venture outside their homes. Whole families began to die of starvation as they hid in terror under beds or blankets. Heracles rushed to the rescue. To aid him in the quest, he chose his strongest, straightest Arrow, dipped in the poisonous blood of Hydra.

Draping his lion skin over his shoulder to serve as a shield, he drew his bow and slayed first one bird, and then another, retrieving his Arrow each time. By the end of the day, he had defeated most of the horrid fowl and chased the remainder far away. Now the starving people of Stymphalia, gaunt but grateful, emerged from cover. With hoarse and feeble voices, they cheered their deliverer.

Heracles had little time to tarry, but pushed ahead to his final labors. In the land of the Hesperides there dwelt a Dragon named Draco—a gargantuan servant of the goddess Hera. Hera—the wife of Zeus—heartily despised Heracles because Zeus had sired him with another woman. So Hera incessantly searched for ways to harm him, and Heracles responded in kind.

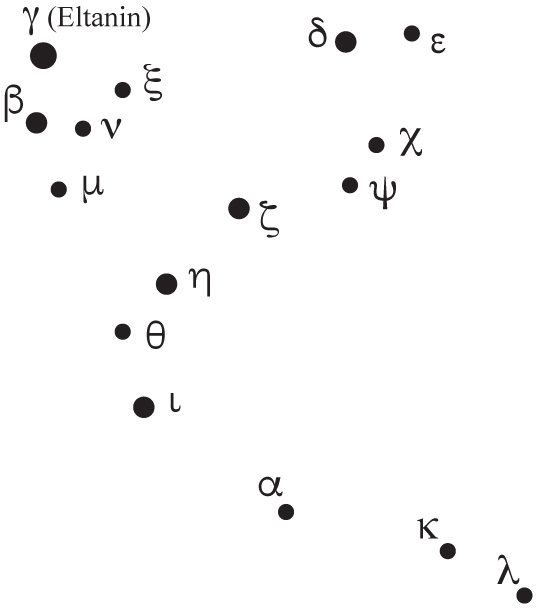

Dragon |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Draco |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Eltanin |

17h 56m 36s |

+51° 29′ 20″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

If Heracles could subdue her serpent, Draco, then he could help himself to the golden apples of the Hesperides—Hera’s prized possessions. Hera had received the apple tree as a wedding gift when she married Zeus and proudly planted it in her garden on the African shore. Here it flourished under the constant care of Atlas’ charming daughters—the Hesperides.15 But the young maidens could not resist nibbling the forbidden fruit. Hera, therefore, employed the Dragon—Draco—as a more reliable watchman.

Draco, with his overpowering size and blazing eyes, proved to be one of Heracles’ greatest opponents because he remained ever vigilant—never sleeping.16 Still, the fearless hero bolted into the fray, without hesitation, and wrestled the scaly serpent to the ground. With immense power, Draco writhed and attempted to wrap his attacker in coils and crush his life away.

All that day the two struggled to gain a commanding grip, until, at last, Heracles managed to pin the Dragon’s slippery head to the ground. Immediately he brought his heavy club down to shatter Draco’s spine. As the lifeless serpent continued to wriggle and squirm, Heracles seized a branch from the apple tree—loaded with golden fruit—and made his departure.

Zeus applauded the astounding success of his stormy son. And when Heracles came to the end of his earthly days, the god placed him high in heaven with his other son, Perseus. In memory of one of Heracles’ many battles, he appears clad in his lion-skin cloak, kneeling in desperate struggle with Draco the DRAGON. His left foot pins the serpent’s head while his right knee rests on the scaly back. His club hovers high, clutched in the right hand, ready to deliver the lethal blow.

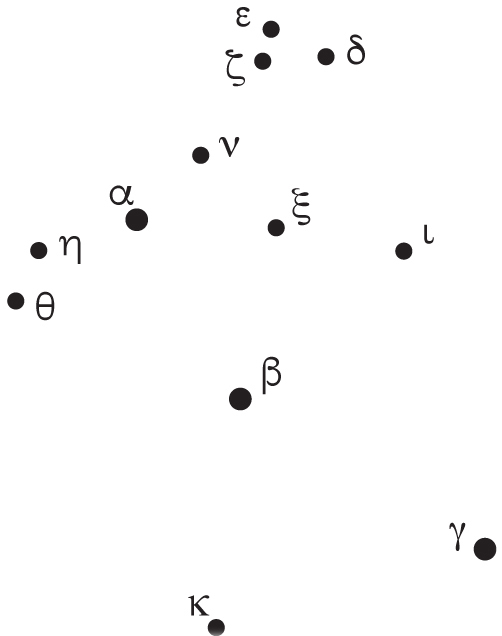

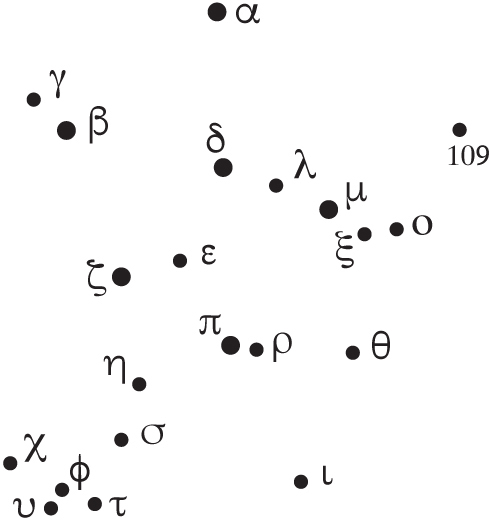

Kneeler |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Hercules |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

β Herculis |

16h 30m 13s |

+21° 29′ 23″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

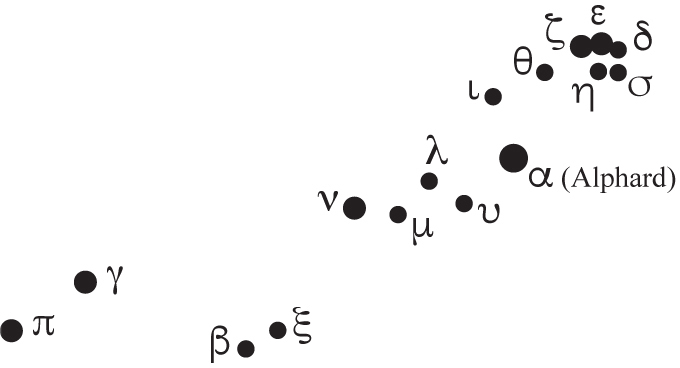

Hydra |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Hydra |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Alphard |

09h 27m 35s |

−08° 39′ 31″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

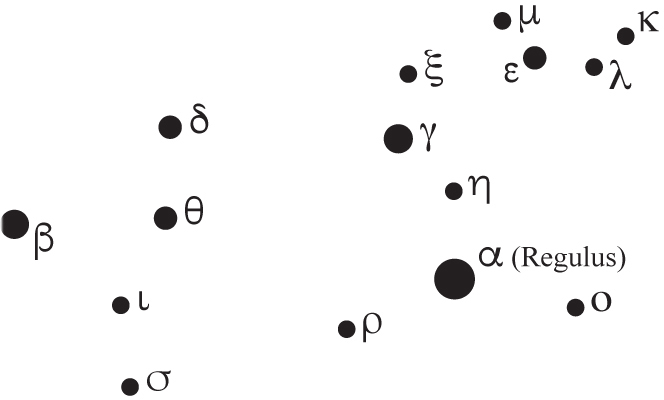

Lion |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Leo |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Regulus |

10h 08m 22s |

+11° 58′ 02″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Because of the position in which he is poised, the constellation of Heracles is called the KNEELER. Lurking farther beneath him is HYDRA, slithering through the stars with her one immortal head still intact. Heracles’ other enemies—the crouching LION and the stealthy CRAB—also appear nearby in the nighttime sky, as does his trusty ARROW that slew the Stymphalian birds.

The honor that Zeus bestowed on Heracles, Perseus, and Andromeda showed that the gods are as quick to favor those who serve them and their fellow man as they are to punish the proud. These heroes’ lives reflected courageous service without conceit. For this, they remain the most famous of mortals.

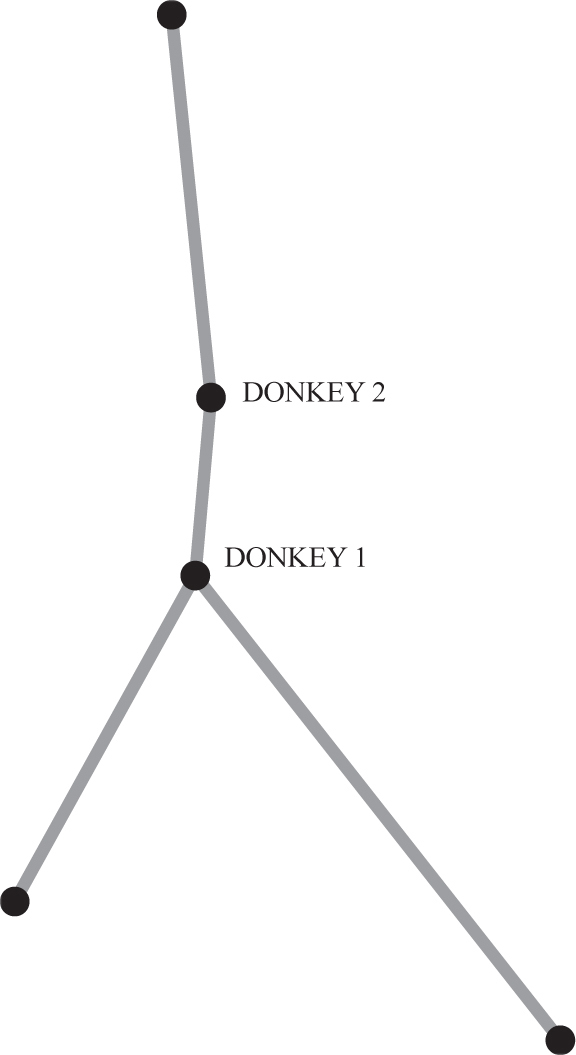

Crab |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Cancer |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

β Cancri |

08h 16m 31s |

+09° 11′ 08″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

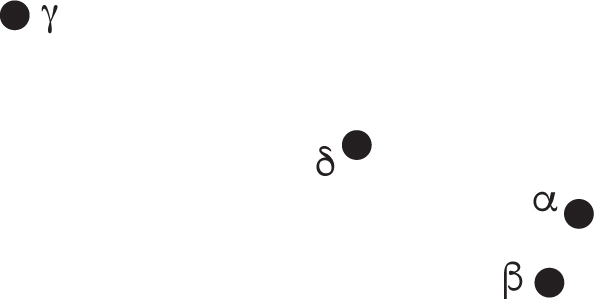

Arrow |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Sagitta |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

γ Sagittae |

19h 58m 45s |

+19° 29′ 32″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |