THE ARGONAUTS AND THE QUEST FOR THE GOLDEN FLEECE

Heracles is famous for the Twelve Labors, but he also searched for other far-flung adventures. Among them, he joined Jason’s crew of Argonauts to sail the Aegean and Black seas and to capture the Golden Fleece.1

Other heroes also committed themselves to the quest. The crew included Asclepius, the ship’s physician; Orpheus, the famed musician; Peleus, the father of Achilles; Laertes, the father of Odysseus; the twin brothers, Castor and Polydeuces; Argus, the builder of the ship Argo; and Tiphys, the talented helmsman.

Tiphys took on the critical task of steering the ship, because he was “expert in predicting rising waves on the broad sea; expert too in predicting storm winds, and in determining a course by sun or star.” His lookout, Lynceus—whose name meant “lynx-like”—aided in navigation. Lynceus had the eyes of a lynx—the keenest vision of the crew.2 Day and night he searched the sea and sky for telltale signs, with eyes squinted against gusts of wind and glare upon the water.

The crew embodied an excellent assembly of men of arete. Wherever they wandered, admiring throngs “marveled as they beheld the beauty and stature of the preeminent heroes.”3 Beyond their physical form and noble bearing, they loomed as men of learning. Some had gained the gift of knowledge from the wise centaur, Chiron.

Like many enlightened mortals, they excelled in music as well. On more than one occasion, they “sang a hymn to the accompaniment of Orpheus’ lyre in beautiful harmony, and round about them the windless shore was charmed by their singing.”4 Above all, they stood tall as spiritual men who remained ever reverent and devoted to the deities.

The journey of the Argonauts arose from events that unfolded many years earlier in the kingdom of Thebes. The Theban queen had given birth to twins—a son and daughter—named Phrixus and Helle. But the king abruptly sent his wife away at the insistence of his mistress, who soon wore the queen’s crown.

The new queen despised her stepchildren and conspired to see them put to death so her own son would one day inherit the throne. To this end, she demanded that her husband sacrifice his own children. This, she claimed, would appease the deities that had sent a famine to plague the land. Day and night, the wicked queen screamed at the king to slay Phrixus and Helle and save the kingdom’s starving subjects.5

At last, the king caved in to his wife’s constant carping, and commanded his royal servants to place the trembling children upon the pyre. All the while, the evil queen, unseen, sneered in the shadows. As the servants lit the loathsome fire, a splendid Ram with a Golden Fleece, sent by Hermes, suddenly darted through the chamber door.

Lowering his head, the Ram lifted the children onto his back and fled toward a safe haven in the east. Fast and far they flew. But as the Ram swam the swirling waters that divide Europe from Asia, poor little Helle, frail and fainting, slipped into the gloomy depths and drowned. On her behalf, the inhabitants along the coast later called the channel Hellespont.

Phrixus grieved deeply for his twin sister and cried a shower of tears while clinging tightly to the Ram’s woolly back. After a weary, woeful journey, the two arrived on the eastern shore of the Black Sea, at the port of Aea in the kingdom of Colchis. The exhausted Ram, his mission fulfilled, submitted himself to Phrixus for a sacrifice to the gods—his last selfless act.6

In obedience, the boy, with sorrow heaped on sorrow, made the somber offering. Then he placed the Ram’s Golden Fleece in a sacred grove to serve as a shrine. There it hung in a “huge oak tree . . . like a cloud that glows red from the fiery beams of the rising sun.”7

Phrixus lived his remaining years in far-off Colchis, while Thebes and all of Hellas withered in drought—by divine decree—for their horrid deed and the death of Helle. Meanwhile, Phryxus’ younger kinsman—Jason—was born to the king and queen of Thessaly and mistreated in a similar manner. When Jason was only an infant, his uncle usurped his father’s throne and plotted to kill the child to secure his own spurious claim. So Jason was rushed to a cave for safekeeping and raised by the kindly centaur, Chiron.

When Jason reached adulthood, he returned to confront his uncle, the king. But the cunning uncle averted the young man’s wrath and lured him into a dangerous quest that was sure to seal his doom. Jason brimmed with youthful boldness and could not say no to the venture.

The king and most of his subjects believed that the deadly drought would end, and the land would flourish again, if a champion only retrieved the Ram’s Golden Fleece from Colchis. Thus the cruel and crafty uncle silently schemed: If Jason somehow succeeded in returning the Fleece, then the kingdom would thrive. But if he died in the attempt, the king would at least be rid of a threat to the throne.

Jason surmised the king’s motive but remained undaunted, delighted by the chance for adventure and pleased to take on the task. Like him, his friends—the heroes of his generation—jumped at the chance to join him.

Soon, Argus began to build a seaworthy ship for the distant journey. First he crafted a keel of heavy oak and laid it on the pebble beach. To this he fastened beams and braces of hardwood, then heavy planking to hold back the furious slap of thundering waves.

He carved a stern that arched above from behind, and a stout bow that thrusted forth from the foredeck. He chose a mast that was sturdy, straight and true, and planed it to perfection. He stepped the mast into the hull and wedged it with a heavy hammer, then straightened it with stays—side to side, and fore and aft.

Now he fitted a yardarm to the mast, with blocks and halyards. He shaped a sail and sewed it—triple-stitched—so it would billow well and hold in a heavy gale. He furled the sail on the yardarm to await the launch, while he fashioned a sturdy pair of steering oars and fifty more for rowing. He chose two stones for anchors and trailed them from the stern with two tightly braided ropes. With these the ship, named Argo, could rest stern-to-beach and not drift off with the ebb and flow of the tide.8

As Argus assembled the ship, Jason trained the crew and assigned specific tasks. At sea, Tiphys would steer from the stern while Lynceus watched from the bow. The others would work the sail when days were fine and the wind blew from behind. At other times, all hands would man the oars and row ahead toward some distant shore.

On making landfall late in the day on a foreign coast, the men would secure the ship and scout for danger. Once assured of safety, some would scoop up leaves for bedding, while others picked up piles of wood. Two would take up the task of sparking a fire by “twirling sticks” between their palms.9 These men also served as cooks—a most important post. Their success or failure meant a healthy, happy crew or one that grumbled with stomachs growling.

With the ship and restless men ready to go, and the sea rising to high tide, the time came at last to launch the Argo. Under blue skies and fair winds, the crew winched and shoved the heavy wooden hulk across the pebble beach and into the swelling surf. Then they steadied the ship, “drew the sail to the top of the mast, and let it down from there. A whistling breeze fell upon it, and on the deck they wound the lines separately around the polished cleats and calmly sped past the long Tisaean headland. . . . A steady wind bore it ever onward.”10

When the wind slackened that afternoon, the men bent to the oars. “Rowing proceeded tirelessly” as they plied the frothy waters of the Aegean Sea. Swiftly, they left Hellas behind in their wake as a hazy sliver on the western horizon.11

The trip began well, but trouble followed. One day, while seeking supplies on the island of Lemnos, Heracles’ faithful servant failed to return to camp. Frantically Heracles searched for the youth along the shore and deep into the forest. Through the night and well past dawn he persisted, but in vain:

Soon the morning star rose above the highest peaks, and the breezes swept down. And at once Tiphys urged them to board and take advantage of the wind. In their eagerness they boarded right away, drew the ship’s anchors up on deck, and pulled back on the halyards. The sail bulged in the middle from the wind, and far out from the shore they joyfully were being borne.12

Only after the island was far behind them did the men discern the absence of Heracles. Above and below the deck they searched, but found no trace. Downtrodden, they saw no option but to keep the course determined by the wind and continue without him.

As the crew probed into foreign waters and ran ashore on strange islands, they encountered unexpected dangers. Often they battled with hostile bands that resented their bold intrusion. Then, when they entered the tempestuous strait of the Hellespont, and the turbulent waters of the Sea of Marmara, the weather turned against them. The men grew weak and weary at the oars as they worked their way through lashing waves and heavy swells.

At last they beached the boat, staggered ashore, and collapsed in the sand. For twelve days and nights they rested, and recouped their strength while waiting for the storm to subside. On the eleventh evening, a halcyon shore bird hovered above the drenched and dejected men as they sat in the wet sand near the Argo. The halcyon arrived as a favorable sign, sent by Rhea, to herald fair weather for sailing. For this, the men offered grateful praise.13

The titan Rhea is the daughter of Gaea—Mother Earth. As such, Rhea holds some control over earth, wind, and sea. She is also the mother of Zeus, Poseidon, and other powerful gods. To be in her good graces is no small matter, but she must be appeased. Most people believe she lives among the Phrygians when she walks upon the Earth. As fate would have it, the Argonauts had happened to find safe haven from the storm on the Phrygian coast, in the shadow of Mount Dindymum.

Before resuming the journey, they carved a wooden likeness of Rhea and carried it up the mountain slope on their shoulders. They placed it in a sacred grove of ancient oaks and stacked flat stones for an altar. Donning wreaths of oak leaves, they offered a savory sacrifice.

As Jason continued to pray and pour libations, Orpheus taught the men to perform the leaping dance in armor—beating their swords against their shields in the manner of Phrygians who worship the matron goddess. Rhea’s closest companions, the Corybantes, praise her in a similar way as they shout and twirl the whirring rhombus and beat the resounding tympanum.14

When the Argonauts received further signs that Rhea had blessed their voyage, the men’s spirits soared. Now they gladly returned to the oars and worked their way through the Sea of Marmara and the narrow passage of the Bosporus.15 After many more days, the arduous outbound journey ended at the distant port of Aea in Colchis, on the farthest reach of the Black Sea.

But there they faced fierce opposition. Aeetes, the king of Colchis, raged within when he heard that Jason intended to take the Golden Fleece to Hellas. The Fleece epitomized the glory and pride of his kingdom. It hung high, in the holiest place, and its value surpassed that of his total treasury.

Still, Aeetes quickly adjudged the tough and determined Hellenic crew that had come so far to tower before him. He feared the result of an outright rejection. So, instead, he freely offered the Fleece to Jason, if the youth would only succeed at a simple test of strength and skill. All he had to do was lash a heavy oak-tree yoke atop the bulging necks of two enormous fire-breathing bulls, then force the team to plow a furrow. Next he needed to plant the teeth of a dragon, and slay the angry army of men that would sprout forth from the dreadful seeds.

Rather than wagging his head and slinking away, as most men would do, Jason shrugged his shoulders, accepted the challenge, and pondered the best way to bring it about. From a balcony above, the king’s sorceress daughter—Medea—witnessed the wager while her longing eyes followed Jason’s every move. To her, Jason looked like Sirius—the shining star, the most luminous of all—“which rises beautiful and bright to behold.”16 Soon, Medea, the enchantress, became the enchanted.

Throughout the night, the anxious crew remained awake and watched the constellations of the Bear and mighty Orion. As they crossed the sky, they marked the passage of time until the dreaded contest at dawn. Meanwhile, Medea came to Jason in darkest night to reveal her love and to offer help with the deadly tasks.17 First, she handed him an ointment that would fend off the fiery breath of the bulls. Then she described how he should defeat the dragon-tooth warriors by simply throwing a stone among them.

Enthralled by the love of the softhearted sorceress, and encouraged by the knowledge he now possessed, Jason prepared for the contest with confidence. At dawn, when the laughing king unleashed the bulls, Jason stepped forward, impervious to the flames that roared from their mouths. Promptly, he yoked them and forced them to plow a furrow while he sowed the seeds of dragon teeth. While he waited and watched for the fearsome army to rise from the furrows—like so many stalks of grain—he swelled himself with courage in the way of the warrior: “He flexed his knees to make them nimble, and filled his great heart with prowess, raging like a boar.”18

Firmly he planted his feet and faced the “earthborn men” as they sprang forth to battle. As Medea had instructed, Jason hefted a heavy rock and hurled it among them. At once, they fell into confusion and turned on each other in furious slaughter. Jason now bolted forward, “as when a fiery star springs forth from heaven bearing a trail of light.” In a flash, he vanquished the remaining foes.19

Aeetes shuddered, aghast at Jason’s baffling success. But he was far from ready to concede defeat. Instead, the deceitful king delayed and offered to hand him the Fleece the following day. Then, secretly, he rallied his royal army and prepared to overpower the band of Hellenes.

Again Medea intervened. That night, she used a spoken charm and a potion of her own concoction to drug the great snake that guarded the sacred grove.20 As the serpent fell into peaceful sleep, she showed the endangered crew the way to escape, unseen, with the Golden Fleece.

With Aeetes’ army hot on their heels, the Argonauts flew to the ship and fled by sea. They brought Medea aboard as well, to protect her from her wrathful father. Heading swiftly westward, they crossed the stormy seas and straits for countless days, and came at last to Hellas with their hard-earned prize. Not long later, Jason deposed his uncle, with the help of Medea, and came to reign as the rightful ruler of Thessaly. Then the Argonaut crew of heroes and friends parted to pursue further valiant adventures in their own native lands.

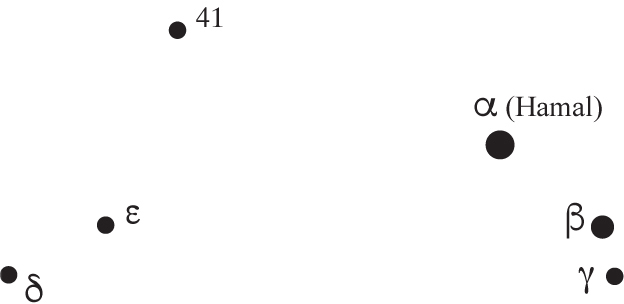

Ram |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Aries |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Hamal |

02h 07m 10s |

+23° 27′ 45″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

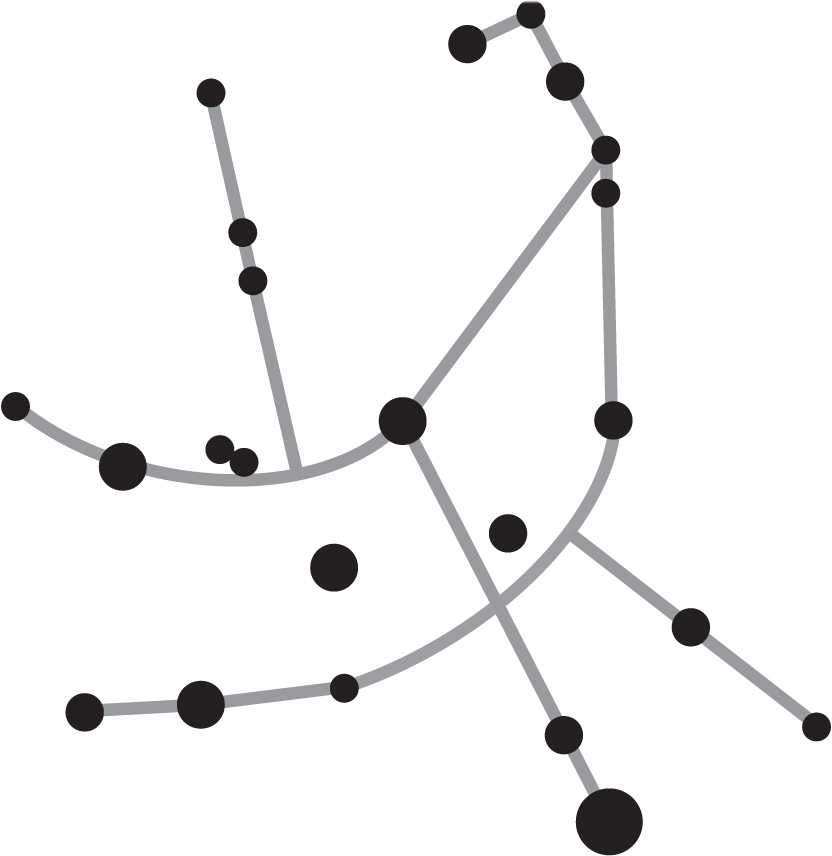

Argo |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Argo Navis |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Canopus |

06h 23m 57s |

−52° 41′ 44″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

For his selfless service and sacrifice, the RAM received a place in heaven. Among the stars, he is seen swimming the Hellespont, with his Golden Fleece just visible above the surface of the sea. His bright muzzle turns back and up toward a guiding astral light, and his horns dip lower down.21 Now his fleece shines for the enjoyment of every earthly being, rather than for one greedy king.

The ship ARGO also attained an eternal course in the stars, where it navigates the celestial mists of the Milky Way. Its steering oars propel it forward, and its stern arches stately overhead. The Argo’s prow is concealed in the fog as it ventures into uncharted skies to the south.22

ORPHEUS, THE GREATEST MUSICIAN

Some of the Argonauts gained similar acclaim for their service to gods and fellow sailors while on the voyage. Orpheus—“the father of songs, and widely praised minstrel”—carried his seven-stringed Lyre aboard to offer inspiration and entertainment during the distant journey.23 The immortals themselves had entrusted this most excellent musical instrument to him.

When Hermes—the messenger god—was but a baby, the precocious child, in search of a toy, had crafted the Lyre from a tortoise shell and a set of sacred cattle horns. Apollo was not pleased when he heard that the horns had come from one of his own beloved bulls. Hermes quickly averted his anger by handing him the sweet sounding Lyre—the first of all stringed instruments.

Apollo—the god of the sun and the arts—beamed with delight. He cherished the Lyre and carried it constantly with him. Then, one day, he gave the instrument to his true love—Calliope—as an expression of his affection.

Calliope—the Muse of epic poetry—soon discovered that the Lyre provided a perfect rhythmic companion to recitations of the stories of old. It proved to be of further worth as an accompaniment to songs, in happy harmony. So, when her son Orpheus showed an amazing aptitude for music, she passed the instrument down to him. In his talented hands, the Lyre offered a delightful addition to sacred songs and epic stories. Thus, in all the ages to follow, every bard of ability has plucked the vibrant strings of a lyre when reciting the tales of Homer and other notable poets.

With the divine instrument carefully cradled in his hands, Orpheus performed stories and songs so enchanting that he wooed the wild beasts that wandered the woods. He even “charmed the hard boulders on the mountains and the course of rivers with the sound of his songs. And the wild oak trees, signs still to this day of his singing, flourish on the Thracian shore . . . where they stand in dense, orderly rows . . . charmed by his Lyre.”24

At the bidding of Chiron, Jason invited Orpheus to join the Argonauts. The musician immediately proved his worth. Right away, the very first day, he revealed how the Lyre offered a steady rhythm for rowers. The instrument also served to calm frayed nerves—ruffled by the rigors of the voyage.

Once, when conflict broke out between two members of the crew, Orpheus grabbed the Lyre in his gifted hands and began to sing a soothing song. “He sang of how the earth, sky, and sea, at one time combined together in a single form . . . and of how the stars and moon and paths of the sun always keep their fixed place in the sky; and how the mountains arose; and how the echoing rivers with their nymphs and all the land animals came to be.”25

The crew—suddenly entranced in silent stares, with mouths opened in awe—watched and listened to the minstrel, and lost all thought of strife. Soon, they merrily continued their course.

On the return journey, the crew succumbed to the eerie enchantment of the sweet-voiced Sirens. These seductive, deadly sea nymphs lived on a rocky island and lured the sailors of passing ships. Their irresistible song drew many men into dangerous shoals and sent them, and their boats, to a watery grave. Fate proved even worse for those who made landfall among the “femmes fatales.” In their loving, lethal embrace, men languished and slowly died.

Even the Argonauts could not resist their charms. “Already they were about to cast the cables from their ship onto the beach.” But, “Orpheus . . . strung his Bistonian Lyre in his hands and rung out the rapid beat of a lively song, so that at the same time the men’s ears might ring with the sound of his strumming.” The Lyre promptly overpowered the song of the Sirens; and “the Zephyr and the resounding waves, rising astern, bore the ship onward”—far away to safety.26

At journey’s end, Orpheus returned to his native land. There, a throng of impassioned women fell in love with the famous bard, as often befalls musicians and poets. When he performed and “beat the ground rapidly with his shining sandal to the accompaniment of his beautifully strummed Lyre and song,” they swooned or became flushed in frenzy.27 Finally, a mob of spellbound women, in jealous rage for his affection, tore him limb from limb.

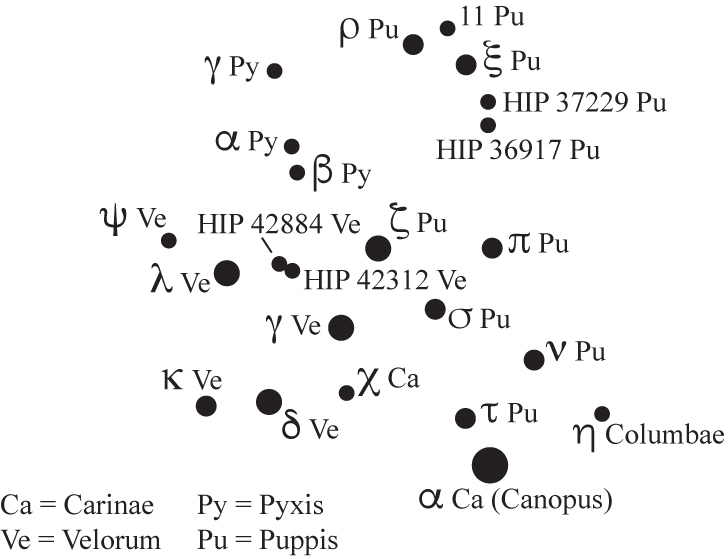

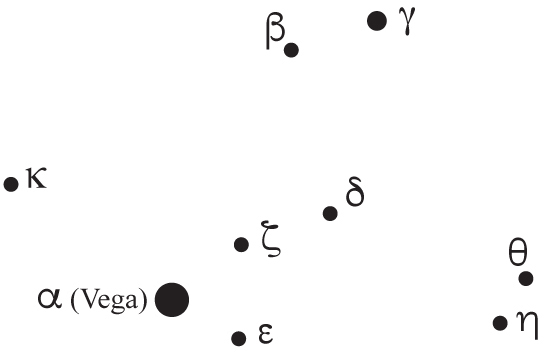

Lyre |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Lyra |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Vega |

18h 36m 56s |

+38° 47′ 01″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Orpheus figured foremost among men as the first of mortal musicians, and as a poet and prophet. Having received his inspiration directly from the Muses, and his instrument as a gift from the gods, no human was ever able to match his musical skill. Zeus honored Orpheus—his grandson through his daughter Calliope—by allowing the LYRE a prominent place in the sky. Here it is marked by one of the brightest of stars. For, as Homer truly said so long ago: “among all men that are upon the earth minstrels win honor and reverence.”28

ASCLEPIUS, THE FAMED PHYSICIAN

One of Orpheus’ shipmates, Asclepius, served as physician and surgeon on the Argo. During the long and perilous voyage he preserved the health and welfare of the men. Asclepius had learned the medicinal use of plants from Chiron and carried his own herbarium close at hand.29 To this he added flora found in foreign lands along the route, whenever their botanical properties proved of worth.

He also applied the means of healing he had learned in Hellas. As a youth, he watched the mysterious methods of slithering snakes and studied their amazing restorative arts. For ages, the wise and wily creatures had devised incredible cures—such as shedding their skins for annual rejuvenation. But they kept their knowledge closely concealed from prying eyes.

Asclepius came to respect and befriend them, and often observed their ways. He even adopted, as his medical symbol, a serpent coiled around a staff.30 Other mortals also esteemed the wisdom of snakes and entrusted them as guardians of sacred temples, shrines, and springs. The Athenians kept a sizable snake on the crest of the Acropolis for this purpose and fed it a monthly fare of honey cake.31

Asclepius became so absorbed in the healing arts that he overstepped his human bounds. After his return from Colchis, he heard that Theseus’ son—Hippolytus—had died without warning. To console the tragedy-stricken father, Asclepius rallied all his awesome powers and brought them to bear on Hippolytus’ lifeless body. With firm persistence and presence of mind, he brought the lad back to the land of the living.

But Zeus was angry. How dare Asclepius to delve into the realm of the gods! In one impetuous moment, Zeus’s thunderbolt darted down to earth and dashed away the life of the famed physician.

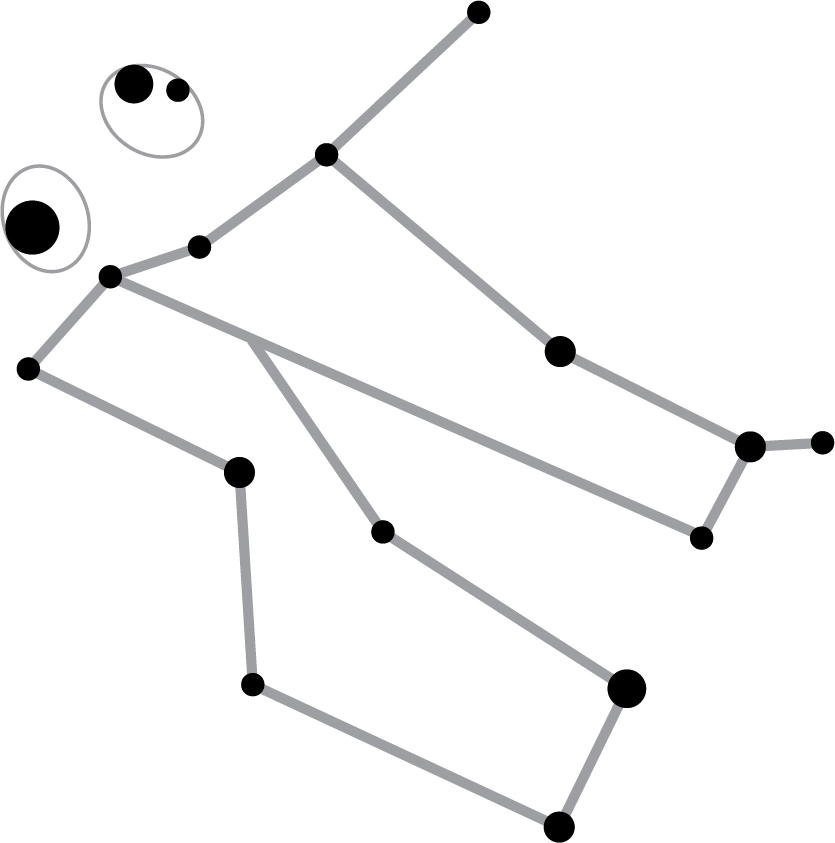

Then, in a fit of remorse, the flighty god commemorated Asclepius’ astounding service to humankind by placing him and his favorite serpent in the sky. Asclepius appears in starry splendor as the SNAKE HOLDER and gently grasps the SNAKE in his caring hands. In this way, the symbol of medicine is forever portrayed at night. And, to this day, physicians with healing hands take the Hippocratic Oath in the name of Asclepius.

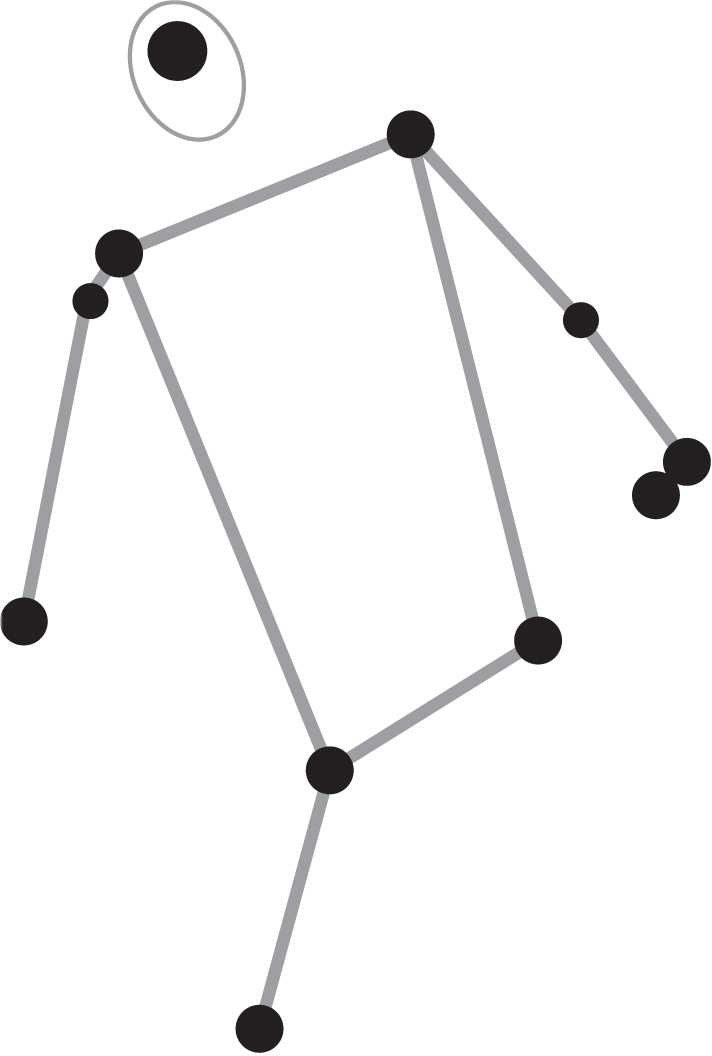

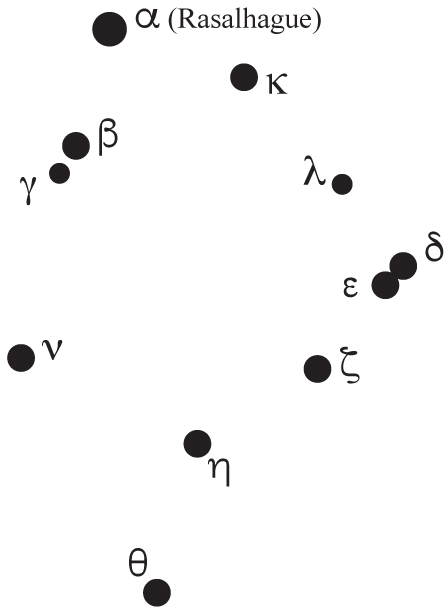

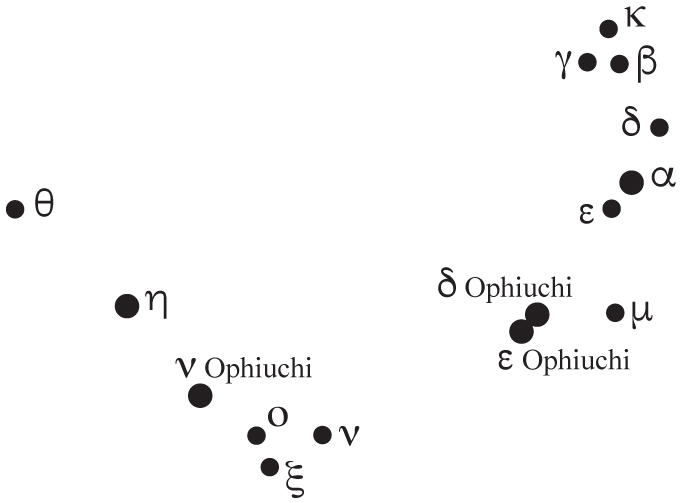

Snake Holder |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Ophiuchus |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Rasalhague |

17h 34m 56s |

+12° 33′ 36″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Snake |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Serpens |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

α Serpentis |

15h 44m 16s |

+06° 25′ 32″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

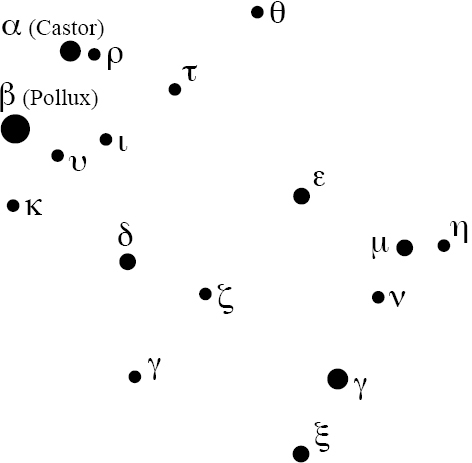

THE DEVOTED TWINS

Two more Argonauts, known as the TWINS—Castor and Polydeuces—earned a place in heaven for their lasting love for one another and for other mortals and gods. Out on the open ocean, the Twins amazed the crew with their uncanny skills of navigation. They often assisted Tiphys and Lynceus to find a favorable route.

The Argonauts also admired the Twins’ divine devotion and called on them as intercessors for safety at sea. During one especially fierce and frightening storm, as the disheartened men fell on the deck in despair, the Twins “stood up and raised their hands to the immortals and prayed.” Slowly, the tempest subsided, and the crew—reassured—returned to their feet.32

Castor and Polydeuces served the Argonauts with such devotion that Zeus “entrusted them with ships of future sailors as well.”33 From that day forward, seafarers through the ages, when seeking reassurance, have looked to the constellation of the Twins—with its two bright stars that mark their heads.34 For added protection in open waters, mariners paint or carve icons of the two men on the bows of their ships. And when two fiery balls of light appear on the masthead toward the end of a storm at sea, reverent seamen thank the Twins for their sign of assurance that all is well.35

The Twins helped the Argonauts find the way back home to Hellas through the same uncanny knack that had helped them find each other as children. Whenever the toddlers wandered apart, they searched with tearful eyes until, at a distance, one spied the other and hurried to a happy reunion. As adults, they remained the best of friends and grew old together. But one day, many years after returning from Colchis, Castor failed to wake up in the morning. His soul had left his aged body and slipped away in the night.

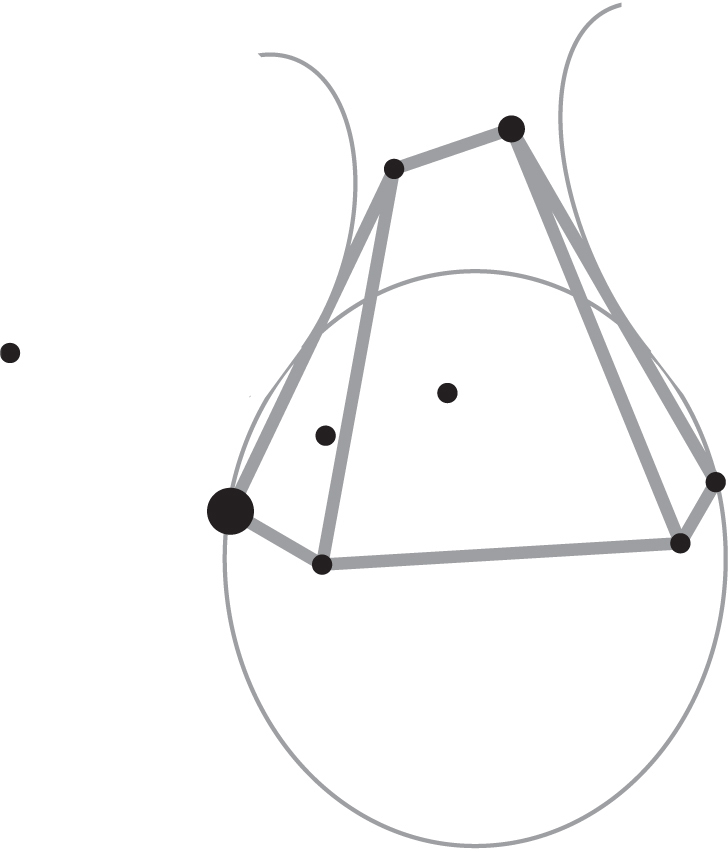

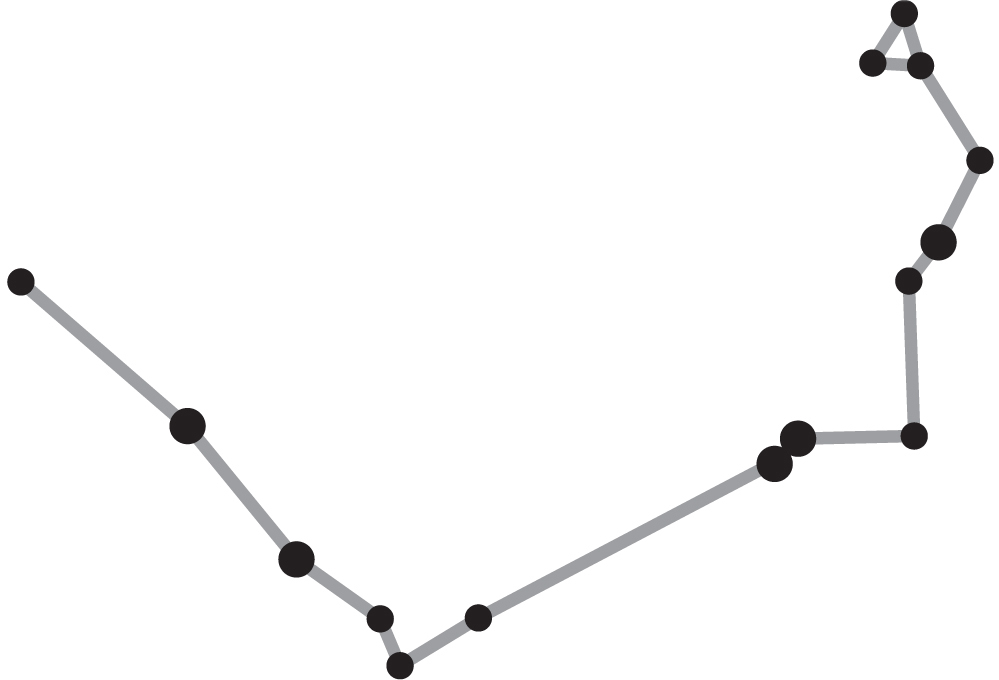

Twins |

|

|

English name |

Greek name |

|

Gemini |

|

|

Latin name |

pronunciation |

|

Pollux |

07h 45m 19s |

+28° 01′ 34″ |

primary star |

right ascension |

declination |

Polydeuces was lost in loneliness and grief. His vision blurred and his hearing became muffled. His mind wandered in aimless confusion, as if in a fog on a trackless sea. For days and months and years he mourned and prayed to the gods to restore his brother or take his life.

At last, Polydeuces’ soul ascended to heaven in happy reunion with Castor. Among the stars they stand, side-by-side, together forever as constant companions, with arms around each other’s shoulders. Polydeuces stands slightly behind and to the right of Castor; while Castor extends his left arm out, as if pointing the way through a narrow passage at sea.

As a constellation, the Twins reflect the love and devotion they held for one another. In life, they honored the gods and served their fellow mortals—free of arrogance and greed. They represented all that Hellenes hold dear. Now, among the stars, they personify the ideals embodied in the tales of ancient skies.