STEP OUTSIDE, AWAY FROM THE LIGHT, into the dark and mysterious night. Stand beneath the boundless skies with eyes toward the shining stars. Move your mind beyond the Earth—beyond the here-and-now.

Suddenly, you see a universe of immeasurable size and immense age. You perceive our planet as a cosmic speck orbiting an ordinary star. This star, called the Sun, is only one of billions of stars in our galaxy. And our galaxy is only one of billions of galaxies in the universe.

In the vastness of space, you see some stars so far away that their rays have raced at the speed of light for two million years to reach you. These rays began their journey toward Earth at the time of the birth of humankind; and to glimpse them now is to peer that far into the past. They have traveled farther than the mind can fathom. Yet they, and all the stars that human eyes can see in the sky, occupy only a tiny corner of the cosmos.

As you gaze upon the grandeur, you share in a ritual repeated since the dawn of time. Our ancestors of ages past stood and pondered the same shimmering stars with awe and wonder. One, who lived two thousand years ago, spoke for people of all times when he said that the heavenly light “draws the gaze of mortals upwards, as they marvel at the strange glow through night’s darkness, and search, with mind of man, the cause of the divine.”1

The ancient Greeks stood foremost among those who searched the stars and contemplated the cosmos. Most of them believed that, long ago, the gods created groups of stars, called constellations, to portray themselves in heaven. They thought the gods assigned other stars to depict the deeds of heroes who had faithfully fought on behalf of fellow mortals. Still other stars illustrated tales of divine protection for the humble, or punishment for the haughty. The Greeks concluded that the constellations, as a whole, offered a god-given gift of moral inspiration—an ethical guide for humans to follow.

Some Greeks, like the poet Aratus (315–240 BC), declared that humans, not gods, had contrived the constellations. He explained that “the men-that-are-no-more noted and marked how to group [the stars] in figures and call all by a single name. For it had passed [their] skill to know each single star, or name them one by one.”2

These words of Aratus provide a profound tribute to our unknown ancestors, who made the earliest efforts to study and understand the heavens. They dared to venture an explanation of the universe, and imparted priceless knowledge and lore. But, sadly, their names have disappeared forever from our collective memory.

The ancient Greeks built upon these timeless ponderings. By the eighth century BC, they had conceived a basic theory of the form of the cosmos. This was recorded by Homer in the Iliad—the earliest western writing. In the Iliad, the god Hephaestus hammered and forged a shield for the warrior Achilles: “On it he fashioned the earth, on it the heavens, on it the sea, and the unwearied sun, and the moon at the full, and on it all the constellations with which heaven is crowned, the Pleiades and the Hyades and mighty Orion, and the Bear . . . that circles ever in its place, and watches Orion, and alone has no part in the baths of the Ocean.”3

In this early age, the Greeks already seemed to conceive of an Earth with surface curvature, if not a complete sphere. They knew the phases of the moon, and the names of certain constellations and asterisms.4 They noted that one constellation, called the Bear, remained ever bright in the night sky—never dipping below the horizon into the sparkling sea. They marked the celestial North Pole with the Bear’s eternal rotation. They perceived that other constellations, as well as the planets, the sun, and the moon, all rose and set beyond Oceanus—that vast body of water thought to encircle the world.

Aratus later described how the stars and constellations “hasten from dawn to night throughout all time.”5 As they travel in unison across the sky, day and night, their relative positions with neighboring stars remain the same; and “all are . . . firmly fixed in the heavens to be the ornaments of the passing night.”6 Aratus and other ancient observers found comfort in the predictable, steadfast nature of the stars. Unlike so many uncertainties that made life on Earth precarious, they could count on the stars to always be where they were supposed to be and behave the way they were supposed to behave.

But among these thousands of reassuring beacons were several stars that seemed to follow no rules. Aratus noted, “Of quite a different class are those five other orbs that intermingle with them and wheel wandering on every side of the twelve figures of the Zodiac,” pursuing “a shifty course.”7 These five wanderers, or planetas (planets), roamed at will in the sky—capricious and free of the constraints of their fixed-star companions.8

Of these wanderers, the morning star named Phosphoros shone forth as the brightest light to bid the night goodbye. Homer described how the day begins when this “star of morning goes out to herald light over the face of the earth—the star after which follows saffron-robed Dawn.”9 On some days, Phosphoros foretold momentous events. Homer praised the morning star for announcing the day that the long-lost Odysseus returned at last to his island kingdom, after an absence of twenty years: “Now when that brightest of stars rose which beyond others comes to herald the light of early Dawn, then it was that the seafaring ship drew near to the island” of Ithaca.10

Hesperos, the evening star, rivaled the beauty of Phosphoros. According to Homer, “the star of evening” was “set in heaven as the fairest of all.”11 In fact, the two stars appeared in essence the same, and seemed to take turns lighting the night sky. At certain times of the year, Phosphoros adorned the morning. At other times, Hesperos graced the evening. But the two never revealed themselves on the same nights.

The explanation for this strange behavior had to await the insight of Pythagoras (c. 572–490 BC). The famed astronomer and mathematician discovered that the two were actually one heavenly body that sometimes shone in the morning and other times in the evening.12 The Greeks renamed the resplendent wandering star for Aphrodite—the goddess of love and beauty.

Later, the Romans called the planet Venus—the second brightest celestial light in the night sky, after the moon. On a clear and moonless night, her glow is capable of casting shadows on Earth. Little wonder that she so amazed ancient observers!

It seemed right that the five radiant, wandering stars—or planets—should be named for the willful gods. Following Aphrodite (Venus) in magnitude came Zeus (Jupiter), the god of sky and storm; Ares (Mars), the blood-red god of war; Cronos (Saturn), the Titan father of Zeus; and Hermes (Mercury), the messenger god that flew fastest in transit across the sky.13

These five praiseworthy planets intrigued observers, but they proved too capricious in motion for practical uses. They could not be counted upon for marking cardinal directions, or noting the passage of time and seasons.

Instead, the Greeks depended on the ever-faithful fixed stars—especially those that circumscribed the celestial North Pole, or wheeled within the zodiac. The zodiac, with its twelve constellations, circles the Earth and envelops the ecliptic path of the sun, moon, and planets across the sky. In ancient times, as the sun slowly made its way from one zodiacal constellation to the next, it marked the start of another month, and the passage of time toward another season.

The Greeks defined nine of these twelve constellations as animals. In fact, the name zodiac comes from the ancient Greek words zodion kuklos, meaning circle of little animals.14 The Greeks also described most of the constellations in the sky as fauna. According to Plato (c. 428–348 BC), “The fixed stars were created, to be divine and eternal animals, ever-abiding and revolving after the same manner and on the same spot . . . circling as in dance.”15

The forty-eight classical constellations, which comprise the core of our modern star groupings, emerged in near-final form by the fourth century BC. Of these, twenty-five depict animals, including thirteen mammals, three birds, three reptiles, two fishes, one crustacean, two arachnids, and one half-mammal, half-fish (Capricornus). In addition, two constellations portray the mythical half-man, half-horse centaurs. Greek lore honors most of these celestial animals for their earthly service to gods and men.

Humans, on the other hand, figure in only a few of the forty-eight constellations. Moreover, mythology often reveals their marginal worthiness. In contrast, one divine being—Virgo—appears in anthropomorphic form, and in the stories of the stars she is held in highest esteem. So too are several constellations that represent the demigods—the heroic sons of divine fathers and mortal mothers. In addition to these, nine inanimate objects make up the remaining constellations.

While ancient observers defined most of the constellations as animals, they also portrayed them in the most important places along the celestial sphere. Furthermore, they defined animals in greater starry detail.16 Human and anthropomorphic anatomy received less representation.17

For example, prominent stars marked animal facial features. But they remained notably missing from most human faces. These faceless humans seem strangely reminiscent of the simplified human stick-figures fashioned in charcoal on walls of Ice Age caves. Alongside these stick-figures, magnificent bison and beasts stampede in splendid detail and vibrant colors of ochre.

Both examples—the constellations and cave paintings—suggest an early human reverence for animals. This, perhaps, was due to their greater prowess, or their importance as a source of provision. Only later did human dominance and domestication of animals lead to belief in their brutish inferiority. Nevertheless, throughout the ages, animals retain their prominent place in the sky.

Many of these animals, and certain humans and gods, had long been the subject of prehistoric stories and oral traditions. Now they gained greater fame as generations of storytellers envisioned them in the stars—assigning them tangible forms as constellations.18

Through the ages, the night sky came to life with animation and drama. But the stories in the stars provided more than simple entertainment. They offered a first essential step toward scientific astronomy by prompting speculation on the matter and meaning of the mysterious heavens.19

After all, science begins with awe and wonder of the unknown. Wonder leads to speculation. Speculation generates theory. Theory is subject to critical analysis and further investigation in a relentless search for facts. This might involve thousands of single contributions during thousands of years. Mythology has often served as a catalyst for this scientific process.

Speculation on the nature of the universe gave birth not just to science, but to philosophy. In ancient Greece, astronomers who contemplated the heavens in the broadest terms became the first philosophers.20 They concluded that the star-studded cosmos, with its predictable and rational motions around the Earth, represented the farthest reaches of an orderly, harmonious whole—a universal oneness.

Thales of Miletus, the famed astronomer and first western philosopher, embraced this holistic approach. Soon he searched for a single substance that surely served as the primal basis of the universe. He concluded that water was the elemental source, while his younger contemporary, Anaximenes, made the same case for air.

Still others, including Anaximander, Pherecydes, Xenophanes, and Heraclitus, perceived of an abstract origin. They envisioned an infinite, indefinable reality—a single cause and source from which all things emerge. Their successors, the three Athenian philosophers—Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle—also embraced this belief. They concluded that this divine reality is tangible in the natural world just as it is intangible in the human mind and soul—as one harmonious whole.21

Greeks believed that to contemplate the natural world, to seek to understand it, and to glorify it in the arts were worthy endeavors that directed the mind toward a higher reality. In accordance with this belief, classical works of art centered on a simple and sublime object that drew attention beyond itself to a larger context—to an ideal greater than itself. Sculptors, for example, sought to fashion figures that achieved realism, then moved beyond reality to a transcendent grace and beauty. Their art represented the real reaching toward the ideal, or nature reaching toward spiritual perfection.

This concept of the real reaching toward the ideal became the standard for individual achievement as well. Greeks used the word arete—personal excellence and virtue—to describe the appropriate pursuit of life to its full physical, mental, and spiritual potential. Several constellations commemorated those who achieved this goal.

In the physical sense, arete alluded to athleticism, strength, and beauty. In the mental sense, it involved the attainment of knowledge and wisdom. In the spiritual sense, it meant goodness, fairness, and humble devotion. In the age of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, arete also involved the attainment of spiritual truth through contemplation.22

Ideally, a person would seek a balance of physical, mental, and spiritual merits, rather than excelling in one at the expense of the others. An obsession with the physical might create a narcissist; the mental a pedant; the spiritual a zealot. In order to possess the proper proportion, a person was wise to follow the two-part advice codified by the earliest western philosophers.

This sage advice was inscribed on a wall of Apollo’s temple at Delphi. The first part said: “Know thyself!” Or, be introspective, and know your strengths and weaknesses in order to work toward improvement. The second said: “Nothing in excess!” Or, maintain harmonious balance in all things.23

This same search for arete, in proper proportion, also found application on the community level. Religious festivals featured contests in athletics, music, drama, and the visual arts. The Greeks would not have thought to splinter these into separate occasions, because they contributed collectively to a higher ideal.

Tragic drama, for example, remained ever aligned with a well-established code of ethics. Performances typically portrayed the theme of divine punishment for excessive pride. The same theme prevailed in the tales of the constellations. In both cases, the stories evinced a longstanding belief in the moral order of the universe.

In the prehistoric past, Greek spiritual awareness was animistic. The Greeks believed that all natural features and phenomena possessed an indwelling spirit. In time, animism gave rise to polytheism, which assigned anthropomorphic forms and personalities to many of these same features and forces of nature. Thus, while animists believed that thunderstorms embodied a powerful spirit, polytheists defined the spirit as Zeus—a god with manlike traits.

But Zeus, and the other gods and spirits, still remained subject to an infinite, indefinable creative force—a divine oneness, a harmonious whole—from which all things arose. This belief in a single creative force is a notable feature of ancient cultures around the globe.24 In Greece, the prehistoric belief emerged in the earliest written records of philosophy and mythology. The works of Hesiod, Anaximander, Plato, and others attest to this.

These thinkers flourished in an environment of free inquiry that allowed them to discuss and disseminate their beliefs. They experienced the advantage of living beyond the shadow of deep-seated despotism. The entrenched empires of the Near East, backed by aristocratic priesthoods, had used the weapon of fear since the dawn of civilization to keep the masses simple and submissive.

But the Greeks had little patience for despots and priests. Instead, they dabbled in democracy, and practiced a personal religion that allowed them to escape the onus of a powerful priesthood. Priests remained in the role of temple officials, while real worship occurred at altars and holy sites in homes, fields, forests, and public places. Each person could communicate directly with the divine through prayers and dreams, or with offerings of food, water, wine, and incense. Festivals, processionals, and performances offered further features of their informal religion.

The early Greeks acceded to no sacred law or scripture—no creed or doctrine. A menagerie of myths—variously interpreted as profound or petty—stood in the place of formal theology, and lack of dogma meant freedom of conscience.

In this environment of free inquiry, philosophers and scientists discovered new paths of learning. They searched for rational explanations of natural phenomena, even while proclaiming the spiritual essence in all things. They never came to the vain conclusion that a thing did not exist simply because they could not probe or comprehend it. For them, the world and the cosmos became compelling rather than menacing. It became a place of beauty rather than fear.

The Greeks certainly differed in their provocative opinions. They often quarreled and even warred among themselves. But they also showed a striking degree of toleration. They glorified singular achievements in philosophy, science, the arts, and other areas that directed attention toward a higher ideal.

The very atmosphere inspired intellectual vitality, curiosity, and elevation of the mind and soul. Socrates provided a striking example of the impulse of the time. As a seeker of truth, he asked penetrating questions rather than dictating his beliefs. He readily rejected conventional thought in his tireless search for enlightenment.

This incessant soul-searching, and dismissal of social assumptions, caused many Greeks to redefine their opinions of the gods. In the past, they had praised the deities for ruling fairly from their pantheon on Mount Olympus. But by the fifth century BC, the gods had lost much of their charm. Popular myths demoted them to a soap opera of family squabbles, romantic trysts, and shocking intrigues that portrayed them as prone to petty jealousies rather than divine justice.25

As the status of deities declined, that of humans ascended. Soon the two resembled each other in villainy and nobility. The gods seemed more like illustrious ancestors than supreme beings. For they, too, stood subject to a universal truth and moral code that so often exposed their folly. By the Classical Period (510–323 BC), mythology tended to emphasize the humanlike frailties of gods, while lauding the godlike achievements of humans.

This mythology was well represented in the celestial panorama. The forty-eight classical constellations, and their associated stories, depicted human and divine interaction that portrayed a code of ethics—a lesson for proper living. The code may be paraphrased as follows: Honor and serve gods and fellow mortals to promote peace and harmony, and avoid arrogance and greed that breed divisiveness and strife.

The constellations consistently conveyed this code by depicting love and devotion among deities and mortals. In contrast, several constellations stressed the negative effects of violating the moral code, and recounted the catastrophic results of vanity and avarice.

The ancient skies came to life with tales of love and devotion and of arrogance and greed. They portrayed spirited passions, bold adventures, exuberant joy, and tragic sorrow, all of which rose and fell on a rolling wave of emotions. These stories voiced the same confident expression that animated tragic and comedic drama, lyric and epic poetry, art, architecture, science, and philosophy.

In addition to impassioned stories and moral lessons, the skies provided a practical guide to the cardinal directions and the passage of time.26 The ancient Greeks believed that the gods gave humans the sun by which to awaken and work. They gave the stars and constellations to tell them when to plant and harvest, when to sail, and when to avoid the stormy seas.27

The movement of the sun and its shadows offered a daytime clock. The stars likewise marked the passage of night. Homer’s Odyssey twice noted the “third watch of the night,” when “the stars had turned their course” around the celestial North Pole. From this, weary watchmen knew that dawn was only a few hours away.28

Five centuries later, Aratus described how to use the “twelve signs of the zodiac . . . to tell the limits of the night.”29 By watching these constellations as they slowly rose over the eastern horizon, a person could determine the time of approaching daybreak. For, as Aratus declared, “the sun himself rises,” always with one of the constellations.30

Classical Greek star lore remained forever enlightening and practical. It was not astrological. Astrology was a Near Eastern invention that only later arrived in the West, after Greek expansion into Asia.31

The Classical era ended with this invasion, as Alexander the Great launched his conquests in the fourth century BC. In the two millennia that followed, empires rose and fell, a hundred generations lived and died, and a heartbreaking amount of ancient learning was lost. But the tales of the forty-eight constellations still remain—in memory of the glory of ancient Greece.

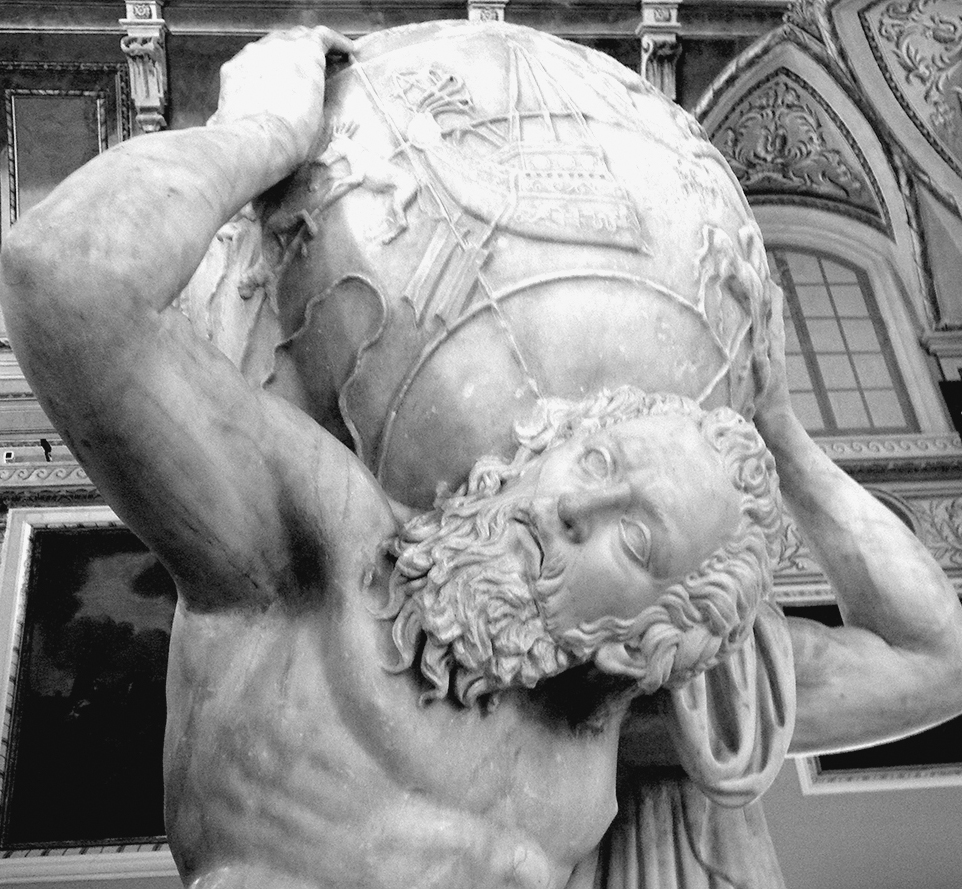

Atlas holding a celestial globe. Sculpture in marble (c. 150 AD) copied from a Hellenistic original of the second century BC. Farnese Collection, National Archeological Museum, Naples, Italy. The Farnese Atlas globe provides the earliest extant images of the Greek constellations. Celestial globe images always appear in reverse, as if viewed from outside the celestial sphere.32