PART TWO

THE MODERN CONSTELLATIONS

In the late ancient, medieval, and renaissance eras, the forty-eight classical constellations continued to grace the skies. Then, around 1600 AD, the human perspective began to expand at a remarkable rate. Scientists and philosophers redoubled their rational queries into the nature of the universe.

Global exploration amassed a wealth of geographical knowledge. Technological advances produced the telescope, and other scientific instruments, to aid investigations. With this revived spirit of inquiry came renewed interest in the celestial sphere, resulting in the addition of forty-one constellations.

The voyages of the Dutch explorer Pieter Keyser took him to southern seas, beneath uncharted regions of the southern sky. Here he gazed on stars that no astronomer of ancient Greece had seen. To fill the vacant space on the celestial map, Keyser contrived twelve new constellations.

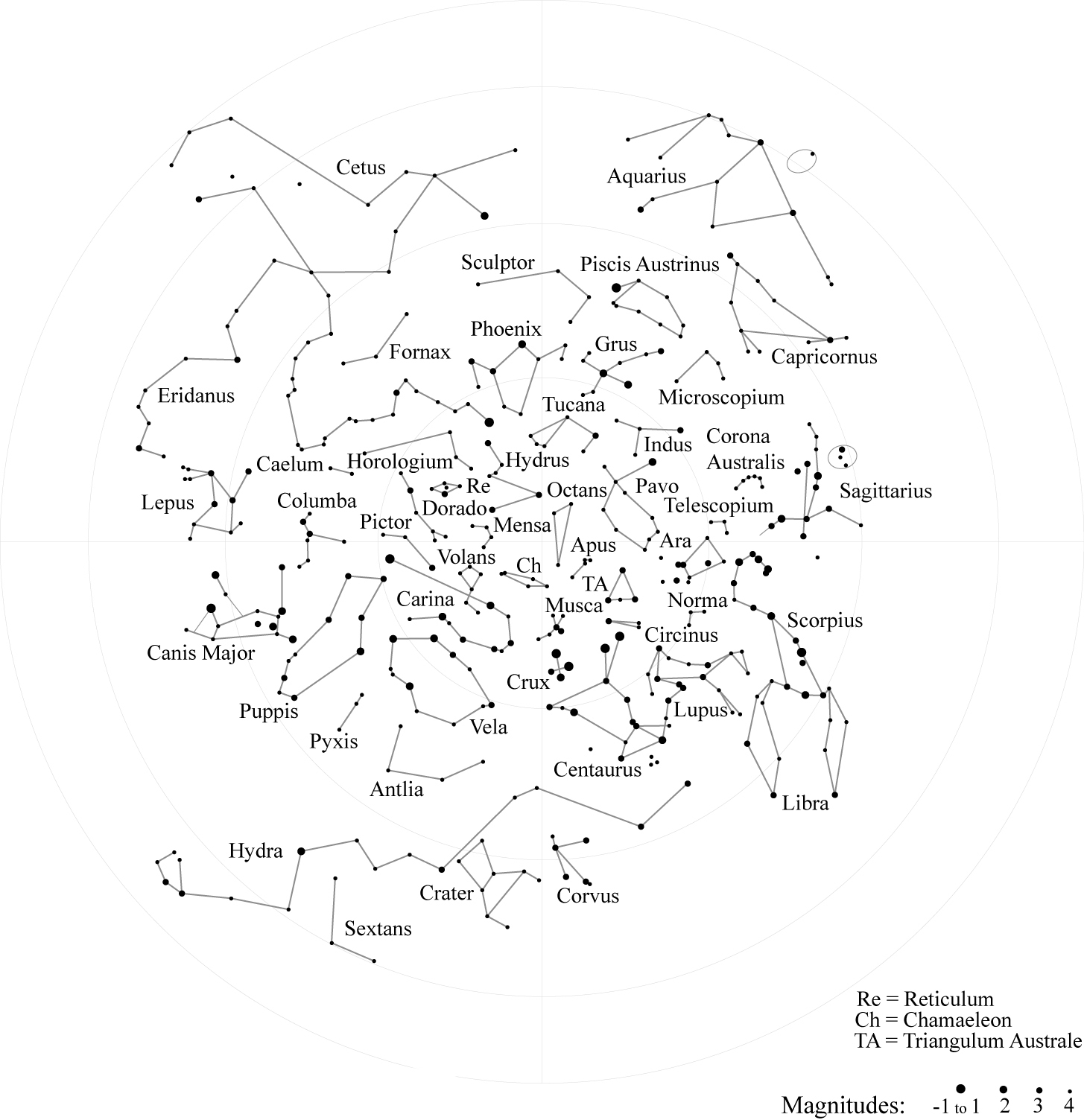

His countryman, Petrus Plancius, popularized these star groupings, and Johann Bayer portrayed them in his fabulous celestial atlas of 1603—the Uranometria.1 These new constellations included Phoenix, Grus, Indus, Pavo, Triangulum Australe, Apus, Musca, Chamaeleon, Volans, Dorado, Hydrus, and Tucana. Most of these depicted exotic or mythical fauna that reflected southern latitudes.

Plancius also proposed four further star groups that later gained the rank of constellation. These included Crux, Columba, Camelopardalis and Monoceros. In the same era, the astronomer Tycho Brahe elevated the ancient asterism of Coma Berenices to the list.

A few years after the addition of these constellations, Galileo Galilei heard reports of the amazing optical properties of a Dutch magnifying toy. He soon developed a twenty-power telescope based on the concept. In November 1609, he turned his telescope toward the sky and discovered details that no human had beheld from the dawn of time.

In December, he sketched the moon’s surface and confirmed the spherical shape of the planets. The following month, he found the four Galilean Moons as they slowly circled Jupiter. All the while, he improved the telescope’s lenses and refined the total design.

The ensuing explosion of new knowledge led to a popular love of astronomy that remains to this day. In this milieu, scientists continued to classify poorly defined regions of the sky. Johannes Hevelius contributed seven new constellations in 1687, including Canes Venatici, Leo Minor, Lynx, Lacerta, Vulpecula, Scutum, and Sextans.

Louis de La Caille followed in 1756, with fourteen southern sky constellations: Telescopium, Norma, Antlia, Pyxis (formerly the mast of Argo Navis), Caelum, Fornax, Sculptor, Microscopium, Octans, Circinus, Pictor, Mensa, Reticulum, and Horologium. Finally, seven years later, La Caille divided the oversize classical constellation of Argo Navis into Vela (formerly the ship’s deck and hull), Carina (formerly the keel and port steering oar), and Puppis (formerly the stern and upper steering oars).

Keyser, Plancius, and Hevelius continued the ancient custom of naming most of the constellations after animals. But La Caille departed from the practice. Instead, he reflected the tone of his time by marking groups of stars as mundane inventions of the scientific and industrial revolutions.

With these, the last of the eighty-eight permanent constellations appeared. Still, the elegant beauty and ancient lore of the forty-eight classical constellations commanded the night sky.

Chapter 7 illustrates the forty-one modern constellations. Each chart is labeled with the Latin name and pronunciation, the English translation, the primary star, and its right ascension and declination. Chapter 8 shows the sharp departure from the realistic forms of ancient constellations to the abstract forms of modern times.