his chapter is filled with a variety of aids to exegesis that must be worked in at various points in the process outlined in Chapter I. The purpose for doing this in a second chapter is twofold: (1) to keep the student exegete from getting bogged down with details in Chapter I, lest there one fail to see the forest for the trees; and (2) to offer a real "how-to" approach to these components—how to read the textual apparatus of the Greek text, how to get the most possible good from an entry in the BDAG Lexicon, and so on.

For many, going through this material will be like the experience of a Pentecostal trying to worship in a liturgical church. At the beginning, such a person can hardly worship because he or she doesn't know when to turn the page or when to kneel. But once the proper kinetic responses are learned, one can concentrate on worship itself. So it is here. These details must be learned. At first they will seem to get in the way or, perhaps worse, seem to be the whole—or most significant part—of the process. But once they are learned well, the times to "stand or kneel" will become more automatic.

In contrast to Chapter I, here I will give several examples of how to go about the process. The various sections of this chapter are intended to function something like a manual; this means the sections are not "easy reading," any more than any manual is. Each of the sections is written with the intent that you should (1) have "hands-on" experience with the various methods and tools and (2) therefore work with the tools themselves, not simply read about them here.

Those without knowledge of Greek will find they can work with most of these materials, except for Sections 2 and 3. For Section 2, you are encouraged to read carefully the bibliographic items noted at the beginning. If you have learned the Greek alphabet, you should also be able to make your way through this section for yourself—at least to see what actually goes into the process. Section 3 is the one part where you cannot work without knowledge of the language. But again, the section has been written so that if you make yourself well acquainted with grammatical terminology and then read the section through slowly and carefully, you will be able to glean a great deal and especially to have a basic understanding of grammatical discussions in the commentaries as you read them.

Sections 1,4,5, and 6 can all be done by those without Greek. I do not say it will be easy going; but if you wish to learn the exegetical process, you must be able to do these various steps. Hence you might as well learn to do it in the same way as those who work with the original language. Much experience with these methods and materials in the classroom has made it abundantly clear that students without Greek who are intent to learn how to do exegesis do all these steps just as well as those work with the language.

Note well: In contrast to the way you read most books, where section headings are skipped over to go immediately to the reading of the material, in this chapter you will need to read the titles of each section and subsection with care. In most cases they also serve as the topic sentence for the paragraph(s) that follow(s).

For Sections 2-4, you should also be aware of an especially helpful book that guides you through all the resource tools and shows you how to use them:

Cyril J. Barber, Introduction to Theological Research (Chicago: Moody Press, 1982).

Section II. 1

The Structural Analysis (See 1.4)

he purpose of step 4 in the exegetical process is to help you visualize the structures of your paragraph and the flow of the argument, as well as to force you to make some preliminary grammatical decisions (on questions of grammar and how syntax is involved, see below in Section II.3). What you are after here is the big picture, the syntactical relationships of the various words and word groups. In Section 3, below, we will examine the various grammatical questions related to morphology—the significance of case, tense, and so forth (exegetical Step 6).

Since the present process is something of an individualized matter, there is no right or wrong here. But the procedure outlined below can be of immense and lifelong benefit if you will take the time to learn it well. Obviously, you may—and should—adapt it to your own style. Whatever you do must finally be practical and useful to you.

1.1. Make a sentence flow.

Probably the most helpful form of structural analysis is to produce a sentence-flow schematic. This is a simplified form of diagramming whose purpose is to depict graphically by coordination and by indentation and subordination the relation between words and clauses in a passage. One begins in the upper left margin with the subject and predicate of the first main clause and allows the paragraph to "flow" toward the right margin by lining up coordinate elements under one another and indenting subordinate or modifying elements. A sentence-flow analysis therefore will include the following steps (1.1.1 through 1.1.5, below), which are illustrated primarily from 1 Cor. 2:6-7.

Those without Greek should be able to follow the process without too much difficulty. For your convenience I have included very literal and "wooden" English "translations." Thus, even without Greek you should be able to follow the procedure (provided, of course, that you know something about English grammar). You will find this a helpful exercise, even from an English translation, provided that you use one of the more literal translations, such as the NASB or NRSV—although even here some of the syntactical decisions will have been made for you. Therefore, you may find it useful to consult a Greek-English interlinear, where an English equivalent appears above (or below) each Greek word of a provided Greek text. See, as the best example:

J. D. Douglas (ed.), The New Greek-English Interlinear New Testament (Wheaton, 111.: Tyndale House Publishers, 1990).

[Note: You will probably want to do your initial work on scratch paper, so that you can arrange and rearrange the sentences until you see the coordinations, balances, subordinations, contrasts, etc.]

1.1.1. Start with the subject, predicate, and object.

It is usually most helpful to begin at the top left corner with the subject (if expressed) and predicate of the first main clause along with the object (or predicate noun). In most instances, it is helpful to rearrange the Greek into the standard English order: subject-verb-object. Thus in 1 Cor. 2:6 one should begin the first line as follows:

λαλοΰ μεν σοφίαν (It is not imperative that one rearrange the

We speak wisdom word order, but you will notice when you come to v. 7 that these words are repeated, and you will want to present them as coordinate elements.)

There are two exceptions to this ordinary procedure:

a. One should be careful not to destroy an author's emphases or chiasms achieved by word order. Thus 1 Cor. 6:1 should begin:

τολμά τις υμών Dare any one of you?

and in 1 Cor. 3:17 one will probably wish to keep Paul's chiastic structure (subject-object-verb/verb-object-subject):

(A) (B) ^ (C) (B) (A)

ε’ίτις τον ναόν φθείρει

τοΰ ΘεοΓ!

φθερεΐ τούτον ό θεός

If anyone the temple destroys

of God

will destroy this one God

b. The last example also illustrates the second exception, namely, when the author's sentence begins with an adverb clause (especially εί, εάν, ότε, όταν, ώς; if, when, since), it is usually best to begin the flow with this clause—even though grammatically it is a subordinate unit.

1.1.2. Subordinate by indentation.

One should subordinate by indentation all adverbial modifiers (i.e., adverbs, prepositional phrases [including most genitives], participial phrases, other adverb clauses), adjective clauses, and noun clauses, preferably under the word or word group being modified.

a. Adverbs (example: 1 Thess. 1:2): ευχάριστου μεν τω θεω πάντοτε

We give thanks to God always

b. Prepositional phrases (example: 1 Cor. 2:6):

λαλοΰμεν σωφίαν

έν τοΐςτελείοις

We speak wisdom

among the mature

c. Genitives (example: 1 Cor. 2:6):

σοφίαν

ού τού αίώνος τούτου

ούδ'ε των αρχόντων

τού αίώνος τούτου

wisdom

not of this age

nor of the rulers

of this age

Note well: Unlike the sentence diagram, an adjective or possessive pronoun in most cases (as in the above example) will naturally accompany the noun it modifies.

d. Adverbial participles (example: 1 Thess. 1:2):

ευχάριστου μεν ...

ποιούμενοι μνείαν

We give thanks ...

when we make mention

e. Adverb clause (example: 1 Cor. 1:27):

ό θεός έξελέξατο τά μωρά

τού κόσμου

ΐνα (See 1.1.4 below

καταισχύνη τούς σοφούς for conjunctions)

God chose the foolish things

of the world in order that

he might shame the wise

/. Adjective clause (example: 1 Cor. 2:6, where an attributive participle functions as an adjective clause):

των αρχόντων

τοΰ αίώνος τούτου των καταργουμένων

of the rulers

of this age

who are being set aside

g. Noun clause (example: 1 Cor. 3:16, where the ότι clause functions as the object of the verb):

ούκ όίδατε ότι

ναός

τοΰ θεοΰ;

έστε

Do you not know that

you are the temple

of God?

Note well: In narratives, where one has direct discourse, the whole direct discourse functions similarly—as the object of the verb of speaking. Thus Mark 4:11:

έλεγεν αύτοΐς·

τό μυστήριον δέδοται

τοΰ βασιλείας ύμΐν

He was saying to them:

The mystery is given

of the kingdom to you

h. Infinitives create some difficulties here. The basic rule is: If the infinitive is complementary, keep it on the same line as its modal; if it functions as a verbal or nominal clause, subordinate as with other clauses. Thus 1 Cor. 3:1:

κάγώ ούκ ήδυνήθην λαλήσαι

ύμΐν

And I was not able to speak

to you

but 1 Cor. 2:2:

έκρινα

είδέναι ού τι

έν ύμΐν

I determined

to know not a thing

among you

1.1.3. Coordinate by lining up.

One should try to visualize all coordinations (e.g., coordinate clauses, phrases, and words, or balanced pairs or contrasts) by lining them up directly under one another, even if at times such coordinate elements appear much farther down in the sentence or paragraph. Note the following illustrations:

1 Cor. 2:6 and 7 should begin at the left margin:

λαλοΰμεν σοφίαν

We speak wisdom

λαλοΰμεν σοφίαν

We speak wisdom

In the ού ... ουδέ (not... nor) phrases of v. 6, one may present the balance in one of two ways, either by coordinating the two genitives themselves:

σοφίαν

ού τοΰ αίώνος τούτου

ούδε των αρχόντων

τοΰ αίώνος τούτου

wisdom

not of this age

nor of the rulers

of this age

or by coordinating the phrase "of this age," which occurs again at the end of v. 7:

σοφίαν

ού τοΰ αιώνος τούτου

ούδε των αρχόντων

τοΰ αιώνος τούτου

wisdom

not of this age

nor of the rulers

of this age

At 1.1.2e above, you will note that we subordinated iva (in order that) but lined up έξελέξατο τα μωρά (he chose the foolish things) and καταισχύνη τούς σοφούς (he might shame the wise). In this way the intended contrasts are immediately made visible.

Note: The problem of coordination and subordination is more complex when there are several elements that modify the same word(s), but which themselves are not coordinate. Thus in 1 Cor. 2:7 there are two prepositional phrases that both modify προώρισεν (he predetermined) but are not themselves coordinate. Here again is a matter of personal preference. Either coordinate

ό θεός προώρισεν God predetermined

προ τών αίώνων before the ages

εις δόξαν ημών for our glory

or, preferably, place the second item slightly to the left of the first (so as not to suggest subordination of one to the other)

ό θεός προώρισεν God predetermined

προ τών αίώνων before the ages

εις δόξαν ημών for our glory

Note: Coordinate conjunctions between words or phrases can be set apart, either between the lines or to the left, but this should be done as unobtrusively as possible. Thus 1 Cor. 2:3, either

έν άσθενεία και έν φόβψ και

έν τρόμω πολλω

in weakness and in fear and

in much trembling

or

έν άσθενεία in weakness

καί έν φόβω and in fear

καί έν τρόμω πολλω and in much trembling

1.1.4. Isolate structural signals.

All structural signals (i.e., conjunctions, particles, relative pronouns, and sometimes demonstrative pronouns) should be isolated either above or to the left and highlighted by underlining, so that one can draw lines from (for example) the conjunction to the preceding word or word group it coordinates or subordinates.

Note: This is an especially important step, because many of the crucial syntactical-grammatical decisions must be made at this point. For example, is this δέ consecutive (signaling continuation) or adversative (implying antithesis)? To what does this ούν (therefore) or γάρ (for) refer? Is it inferential (drawing a conclusion) or causal (giving a reason), and on the basis of what that has been said above? Does this ότι or ίνα introduce an appositional clause (epexegesis) or an adverb clause?

Thus in 1 Cor. 2:6:

δέ but

λαλοΰμεν σοφίαν We speak wisdom

(In a notation [see 1.1.6 below], one should indicate something like this: This is an adversative δέ, probably to all of 1:18-2:5 but espe-dally to 2:4-5, where Paul has denied having spoken in words of persuasive wisdom.)

Also further in v. 6:

λαλούμεν σοφίαν We speak wisdom

έν τους τελείους among the mature

δε but

σοφίαν ... wisdom ...

Also in v. 6, note that the των with καταργουμένων functions as a relative pronoun. Thus:

των αρχόντων

τού αίώνος τούτου των καταργουμένων

of the rulers

of this age

who are being set aside

1.1.5. Color-code recurring words or motifs.

When the entire paragraph has been thus rewritten, one might want to go back and color-code the recurring motifs in order to trace the themes or ideas crucial to the flow of the argument. Thus the final display of 1 Cor. 2:6-7 should look something like this:

δε

λαλούμεν σοφίαν έντόίς τελείους δε

σοφίαν

ού τού αίώνος τούτου

ούδέ των αρχόντων

τοΰ αίώνος τούτου τών καταργουμένων

άλλα

λαλούμεν σοφίαν έν μυστηρίω θεού

τήν άποκεκρυμμένην ήν

ό θεός προώρυσεν

προ τών αιώνων εις δόξαν ήμών

f|V

ούδεις εγνωκεν

των αρχόντων

του αίώνος τούτου

But

we speak wisdom among the mature but

wisdom

not of this age

nor of the rulers

of this age

who are being set aside But

we speak wisdom

in a mystery of God

which had been hidden which

God predetermined

before the ages for our glory

which

none knew

of the rulers

of this age

Note: There are three motifs that should be isolated:

1. Paul and the Corinthian believers: λαλοΰμεν (we speak), έν τοΐς τελείοις (among the mature), λαλοΰμεν (we speak), εις δόξαν υμών (for our glory);

2. those who, by contrast, are of this age: ού τοΰ αίώνος τούτου (not of this age), ούδε των αρχόντων, etc. (nor of the rulers, etc.), των καταργουμένων (who are being set aside), ούδείς εγνωκεν, etc. (none of the rulers, etc., knew);

3. the descriptions of the wisdom of God: σοφίαν θεού (wisdom of God), έν μυστηρίω (in a mystery),την άποκεκρυμμένην (which had been hidden), ήν ό θεός προώρισεν προ των αιώνων (which God predetermined before the ages).

1.1.6. Trace the argument by annotation.

The following examples are given not only to illustrate the process but also to show how such structural displays aid in the whole exegetical process.

Example 1. In the following sentence flow of Luke 2:14, one can see how the structures might be differently arranged, and how an argument from structure might help the textual decision to be made in Step 5 of the exegetical process (1.5). You will note that the NA27 text correctly sees this verse as a piece of Semitic poetry (distinguished, you will recall, by parallelism, not necessarily by meter or rhyme) and sets it out thus:

δόξα έν ύψίστοις θεω

και έπΐ γης ειρήνη έν άνθρώποις ευδοκίας

There is a textual variation between ευδοκίας (gen. = of goodwill) and ευδοκία (nom. = goodwill). If the original text were ευδοκία (nominative), then one would have what might appear to be three balanced lines:

δόξα θεφ

έν ύψίστοις

καί

ειρήνη

επίγής

ευδοκία

έν άνθρώποις

Glory to God

in the highest

and

peace

on earth

goodwill

among people

But a more careful analysis reveals that the poetry breaks down at a couple of points by this arrangement. First, only the δόξα line has three members to it. This is not crucial to the poetry, but the second item is crucial, that is, the presence of καί between lines one and two, and its absence between lines two and three. If the original text is ευδοκίας (genitive), however, good parallelism is found:

δόξα

θεω

έν ύψίστοις καί ειρήνη

έπιγης

έν άνθρώποις

ευδοκίας

Glory

to God in the highest and peace

on earth

among people

of goodwill

In this case ευδοκίας does not break the parallelism; it merely serves as an adjecival modifier of άνθρώποις (people): either characterized by goodwill or favored by God (see II.3.3.1). Note also that I have tried to keep the actual parallels coordinate (to God/among people; in the highest/on earth).

Example 2. Frequently key exegetical decisions are forced upon you in the process of making the sentence flow. It is probably best to con-suit the aids right at this point (see II.3.2) and try to come to a decision, even though such matters will finally be taken up as part of Step 6 (see II.3 below). Thus, in 1 Thess. 1:2-3 there are three such decisions, which have to do with the placement of the modifiers:

1. Where does one place πάντοτε (always) and περί πάντων ύμών (for all of you)? with εύχαριστοΰμεν (we give thanks) or μνείαν ποιούμενοι (making mention)?

2. Where does one place άδιαλείπτως (unceasingly)? with μνείαν ποιούμενοι (making mention) or μνημονευοντες (remembering)? Neither of these affects the meaning too greatly, but it will affect one's translation (e.g., compare the TNIV and the NRSV on the second one). But the third one is of some exegetical concern.

3. Who is έμπροσθεν του θεοΰ (in the presence of God)? Is Paul remembering the Thessalonians before God when he prays? Or is Jesus now in the presence of God?

Decisions like these are not always easy, but basically they must be resolved on the basis either of (a) Pauline usage elsewhere, or (b) the best sense in the present context, or (c) which achieves the better balance of ideas.

Thus the first two may be resolved on the basis of Paul's usage. In 2 Thess. 1:3 and 2:13 and 1 Cor. 1:4, πάντοτε unambiguously goes with a preceding form of εύχαριστειν. There seems to be no good reason to think it is otherwise here. So also with άδιαλείπτως, which in Rom. 1:9 goes with μνείαν ... ποιούμαι.

But the decision about έμπροσθεν τού θεού is not easy. In 1 Thess. 3:9, Paul says he rejoices ’έμπροσθεν τοΰ θεοΰ. This usage, plus the whole context of 1 Thess. 1:2-6, tends to give the edge to Paul as the one who is remembering them έμπροσθεν τοΰ θεοΰ, despite its distance from the participle it modifies.

Thus the text will be displayed as follows:

εύχαριστοΰμεν τώ θεώ πάντοτε

περί πάντων ύμών

ποιούμενοι μνείαν

άδιαλείπτως

επί των προσευχών ήμών

μνημονεύοντες ύμών τοΰ έργου

τής πίστεως

|

και |

τού κόπου |

|

τής αγάπης | |

|

καί |

τής υπομονής |

τής έλπίδος

τοΰ κυρίου ήμών

Ίησοΰ Χριστοΰ

έμπροσθεν τοΰ θεοΰ και πατρός ήμών

We give thanks to God

always for all of you

making mention

unceasingly in our prayers

remembering your work

of faith and labor

of love and endurance of hope

in our Lord

Jesus Christ

in the presence of our God and Father

Example 3. The following display of 1 Thess. 5:16-18 and 19-22 shows how the structure itself and the choices made at II. 1.1.3 and 1.1.4 lead to a proper exegesis of the passage.

χαίρετε

πάντοτε

προσεΰχεσθε

άδιαλείπτως

ευχαριστείτε

εν παντί

τοΰτο θέλημα

θεοΰ

έν Χριατοΰ Ίησοΰ εις υμάς

in Christ Jesus for you

The question here is whether τοΰτο (this) refers only to the third member above or, more likely, to all three members.

It should become clear by this display that we do not here have three seriatim imperatives but a set of three, all of which are God's

will for the believer. That observation leads one to expect a grouping in the next series as well, which may be displayed thus:

μή σβέννυτε τό πνεύμα μή έξουθενειτε προφητείας

δε

δοκιμάζετε πάντα

κατέχετε τό καλόν

άπέχεσθε

άπό παντός είδους

πονηρού

Do not quench the Spirit do not despise prophesyings

test all things

hold fast the good

abstain

from every form

of evil

Note how crucial the adversative δέ (but) is to what follows. Note also that the last two imperatives are not coordinate with δοκιμάζετε (test) but are coordinate with each other as the two results of δοκιμάζετε.

Finally, one may wish to redo the whole in a finished form and then trace in the right margin the flow of the argument by annotation, as in the following example.

Example 4. The following display of 1 Cor. 14:1-4 shows how all the steps come together in a finished presentation of the structure of a paragraph (v. 5 has been omitted for space reasons), including the annotations:

(1) διώκετε τήν αγάπην1

δε2

ζηλοΰτε τά πνευματικά ιιάλλον δε3 ινα

προφητεύητε γάρ4

λαλεΐ5

ούκ άνθρώποι,ς άλλα θεώ

(2) ό λάλων γλώσση

γαβ

(3)

δε6

_ό προφητεΰων

(4)

ό λάλωνγλώσση δε

ό προφητεύων

ούδείς ακούει δε

λαλεΐ μυστήρια

πνεΰματυ

λαλεΐ

ανθρώπους οικοδομήν καί παράκλησυν καί παραμυθίαν

ουκοδομεΐ εαυτόν7 οίκοδομεΐ εκκλησίαν

the one who speaks in tongues speaks5

not to people but to God

Tor

no one understands but

he speaks mysteries by the Spirit

but6

(3)

(4)

the one who prophesies speaks

to people edification and exhortation

_ and consolation

the one who speaks in tongues

edifies himself7

but

the one who prophesies - edifies the church

Three themes need to be color-coded: προφητεύειν (prophesy), λαλεΐν γλώσση (speak with tongues), οίκοδομ- (edify, edification).

Notes:

1. This imperative follows hard on the heels of chap. 13.

2. The δέ here is consecutive and picks up the thrust of chap. 12 (see the repeated ζηλοΰτε from 12:31).

3. But now Paul comes to the real urgency, which is not really hinted at until now. He wants intelligible gifts in the community, and he singles out prophecy to set in contrast to tongues, which is the issue in Corinth.

4. γάρ will be explanatory here, introducing the reason why μάλλον δέ Iva ...

5. Paul begins with their favorite, tongues, and explains why it needs to be cooled in the community. But he clearly affirms tongues for the individual. The tongues speaker (a) speaks to God and (To) speaks mysteries by the Spirit (cf. 14:28b). Cf. v. 4, where Paul also says that one who speaks in tongues edifies oneself.

6. But in church one needs to learn to speak for the benefit of others. (The three nouns, which are the objects of the verb, function in a purposive way and give guidelines for the validity of spiritual utterances; but the only one to be picked up in the following discussion is οικοδομή [building up].)

7. One more time, but now with οίκοδομή as the key to the contrast. Note that the edifying of oneself is not a negative for Paul— except when it happens in the community.

1.2. Make a sentence diagram.

At times the grammar and syntax of a sentence may be so complex that one will find it convenient to resort to the traditional device of diagramming the individual sentences. The basic symbols and procedures for this are illustrated in many basic grammar books. See Harry Shaw, Errors in English and Ways to Correct Them, 2d ed. (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1970), pp. 383-90. This technique is particularly helpful for English exegesis and may serve to clarify the Greek text as well.

Section II.2

Establishing the Text (See 1.5)

he first kinds of materials from your "provisional list of exegetical difficulties" (see 1.3.2) that need investigation have to do with the original text. Which of the variants found in the manuscript tradition most likely represents the actual words of the biblical author? This section is intended to help you learn the process for making such decisions. Since this tends to be a very technical field of study your first concern should be to understand the material well enough so that you feel comfortable with the textual discussions in the various secondary sources.

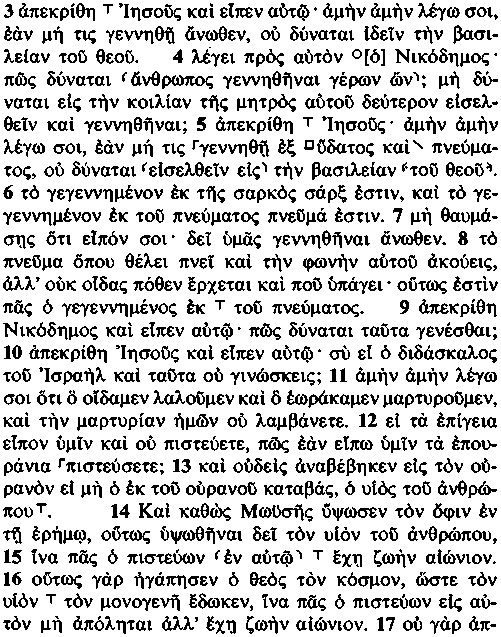

Our hands-on concerns in this section are two: (1) to teach you how to read the apparatuses in the two basic editions of the Greek New Testament, Nestle-Aland, Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th ed. (NA27), ed. B. and K. Aland et al. (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1993), and the United Bible Societies' The Greek New Testament, 4th ed. (UBS4), ed. B. Aland et al. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1993); and (2) to illustrate the process of making textual decisions by going through the several steps. The illustrations will be taken from the three sets of variants in John 3:15 and 13.

2.1. Leant well some basic concepts about NT textual criticism.

The discussion in this section assumes you have read carefully one of the following surveys:

Gordon D. Fee, "The Textual Criticism of the New Testament," in The Expositor's Bible Commentary, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1979), vol. 1, pp. 419-33.

Bruce M. Metzger (ed.), A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2d ed. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1994), pp. 1*-16*.

Michael W. Holmes, "Textual Criticism," in New Testament Criticism and Interpretation, ed. D. A. Black and D. S. Dockery (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1991), pp. 101-34.

For a more thorough study of all the matters involved in this discipline, you will want to look at one or both of the following:

Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 3d enlarged ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). [JAF 94]

Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 2d ed., trans. E. F. Rhodes (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1989).

It is not our intention here to go over all that material again. However, some basic matters need to be learned well:

2.1.1. The word variant or variation unit refers to those places where two or more Greek manuscripts (MSS) or other evidence, when read side by side, have differences in wording.

2.1.2. All variants are either accidental (slips of eye, ear, or mind) or deliberate (in the sense that the copyist either consciously or unconsciously tried to "improve" the text he was copying).

2.1.3. Every variation is one of four kinds:

1. Addition: A scribe (copyist) added one or more words to the text he was copying. In NA27 the siglum for "additions" is T (see p. 52* in the NA27 Introduction). This means that the MSS listed in the apparatus after this siglum have some additional words that are not found in the MSS followed by NA27 at this point.

2. Omission: A scribe omitted one or more words from the text he was copying. In NA27 the sigla ° and av are used for "omissions" (° for one word; DN for two or more). (It should be noted that it depends on one's perspective as to whether a word is "added" or "omitted." If MS A has a word not found in MS B, then either A "added" something to a text like B or, conversely, B "omitted" something from a text like A.)

3. Transposition: A scribe altered the word order (or sometimes sentence order) from that of the text he was copying. In NA27 the siglum for transpositions is ״ (or sometimes ״, when "substitution" is also involved).

4. Substitution: A scribe substituted a word or words for one or more found in the text he was copying. The siglum for this is either r (for one word) or ״ (for two or more words).

2.1.4. The causes of variation are many and varied. Accidental variations are basically the result of slips of eye, ear, or mind. Deliberate variations may be for a variety of reasons: harmonization, clarification, simplification, improvement of Greek style, or theology. You need to be aware that the vast majority of "deliberate" variants were attempts to "improve" the text in some way—to make it more readable and/or understandable.

2.1.5. The goal of textual criticism is to determine which reading at any point of variation is most likely the original text, and which readings are the errors.

Note well: Not all textual variants in the NA27 apparatus have exegetical significance, in the sense that the meaning of the text is affected in some way. The task of Step 5 in the exegetical process (1.5) is to establish the original text for all variation units; but only those that will affect the meaning are to be discussed in your paper, and even then one must learn to discriminate between those variants that require substantial exegetical discussion and those that may be noted only in passing. The ability to discriminate will come with experience. Some suggestions will emerge in the discussion that follows.

2.2. Set out each of the textual variants along with its supporting evidence.

Although with much practice you may learn to do this simply by looking at the apparatuses, it is best at the beginning to write out

JC 1,17! · 1J 4,7! IP 1,23 ♦ Ml 18,3

these data for yourself. Let us begin with the variants in John 3:15 in the Nestle-Aland text (which is included on p. 62 for your convenience). The first of these is signaled by the marksr י around εν αύτω (in him), the second by the mark T following αύτω.

For the first variation unit (έν αύτω, etc.) you will find three basic variants listed in the apparatus, with supporting evidence. Note that two further variants are to be found in parentheses: according to UBS4,579 read αύτω only, while A reads έπ ’ αύτόν. [Note: The parentheses around A at this point in the NA27 apparatus means that the Greek word or words in the parentheses should substitute (or, with a plus sign, should be added) for the immediately preceding word(s) and thus form another variant; note that A is then included in the listing for the basic variant.] This means that the editors consider A to be supporting the variant εις αύτόν; however, this is problematic, so for textual purposes the επ’ αύτόν should be considered yet another variant. You should also note that in NA27 the reading of the text, when it does appear in the apparatus, is always listed as the final item. This information can now be displayed as follows:

|

(1) |

έν αύτω (in him) |

ip75 B Ws 083 pc aur c 1 r1 vg: |

|

(2) |

έπ’ αύτω (on him) |

sp66 L pc |

|

(3) |

αύτω (him) |

579 |

|

(4) |

εις αύτόν ("into" him) |

^63vid κΘψ 086/113 33 HR |

|

(5) |

έπ’ αύτόν (on him) |

A |

The supporting evidence can be interpreted by reading pp. 54*-59* and 63*-76* in the Introduction to NA27, and by checking the manuscript information given on pp. 684-718. Thus, for example, variant 1 is supported by T>75 (a third-century papyrus), B (a fourth-century uncial), Ws (the text supplied from another source for this fifth-century uncial), 083 (a sixth-seventh century uncial), plus a few others and four Old Latin MSS. (See pp. 96-180 in the Alands' Text for helpful information on the various MSS.) In this way one can briefly analyze the support for each of the variants. Note that the Gothic 2Jt listed for variant 4 includes the vast majority of the later Greek MSS (see p. 55*).

[A word about the witness of P63 and the siglum v1d (= apparently): This sixth-century papyrus fragment has a lacuna (hole) that makes it not quite possible to determine whether the preposition before αύτόν is ΕΙΣ or ΕΠ’. Earlier editors, including the NA26, thought it most likely resembled an επ’, which is still found in the apparatus of UBS4. But more recent studies have assumed that since it also reads the additional words μή άπόληται άλλ’, it most likely supports the majority text here as well.]

Similarly, the second variation unit can be displayed thus. (The 16 in parentheses in the apparatus indicates that the editors consider the variant a likely assimilation to v. 16.)

(1) μή άπόληται άλλ’ $>63 A ΘΨ/13 SDR lat sys P h· boms (should not

perish but)

(2) omit $>36$>66$>75א BLTWS 083 086/133565

pc a fc syc co

In this case there are additional witnesses from the versions. For example, variant 2 is supported by Old Latin MS "a" (fourth century) and the corrector of Old Latin MS "f" (f itself is a sixth-century MS), plus one of the Old Syriac (the Curetonian) and the Coptic versions (except for a MS of the Bohairic).

For more information about further supporting witnesses, one can turn to the UBS4. Because this edition was prepared primarily for translators, it has fewer variation units in its apparatus; those that do appear were chosen basically because they were judged to have exegetical/translational significance. Also for translational purposes, the two variation units have been combined into one in the apparatus. Two things should be known about this additional evidence:

a. Although the UBS Greek and versional evidence is generally highly reliable, there are occasional conflicts with NA27 (as with ip63v1d in this example). In such cases Nestle-Aland can be expected to be the more reliable, since its apparatus was reworked rather thoroughly for this edition.

b. The editors of the UBS text indicate that they have thoroughly reviewed the patristic evidence and therefore that "the infer-

mation provided is as reliable as any information in this difficult area can be" (p. 19*). Reality, however, falls far below this ambitious statement. The use of uncritical editions of some Fathers and the general lack of evaluation of this evidence puts it in some jeopardy (a case in point being the four listings of Cyril of Alexandria). On this whole question, see G. D. Fee, "The Use of Greek Patristic Citations in New Testament Textual Criticism: The State of the Question," in Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism, with Eldon J. Epp (Studies and Documents 45: Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1993), pp. 344-59. Thus the UBS patristic evidence must be used with great caution, especially if one wants to make a point of it in some way.

For still further information about supporting evidence, one might consult the edition by Tischendorf [JAF 122] or, if one is especially eager, that by von Soden [JAF 121]. Keys to the reading of these two apparatuses can be found in J. Harold Greenlee, An Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism, rev. ed. (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, 1995). [JAF 89]

You are now prepared to evaluate the variants on the basis of the external and internal criteria (see Metzger's Textual Commentary, pp. 10*-14*). Before proceeding, however, it should be noted that the first variant in John 3:15 would not have been an easy one for a student to have resolved on his or her own. It was chosen partly for that rea-son—to acquaint the student with the kinds of questions that need to be asked and the kinds of decisions that need to be made.

2.3. Evaluate each of the variants by the criteria for judging external evidence.

These criteria are given in Metzger's Textual Commentary, pp. 11*-12*. Basically, they are four:

2.3.1. Determine the date of the witnesses favoring each variant.

The concern here has chiefly to do with the earlier evidence—all of the cursives date from the tenth century and later. Do some of the variants have earlier supporting evidence than others? Does one of the variants have the majority of early witnesses? Do any of the variants have no early support?

2.3.2. Determine the geographical distribution of the witnesses (especially the earlier ones) favoring each variant.

The importance of this criterion is that if a given variant has early and geographically widespread support, it is highly probable that this reading must be very early and near to the original, if not the original itself.

2.3.3. Determine the degree of textual relatedness among the witnesses supporting each variant.

This criterion is related to 2.3.2. Here, one is trying to determine whether the witnesses for a given variant are all textually related or whether they come from a variety of textual groups. If, for example, all the witnesses for one variant are from the same text type, it is pos-sible—highly probable in many instances—that that variant is a textual peculiarity of that family. For a partial listing of evidence by text type, see Metzger's Textual Commentary, pp. 14*-16*.

2.3.4. Determine the quality of the witnesses favoring each variant.

This is not an easy criterion for students to work with. Indeed, some scholars would argue that it is an irrelevant, or at least subjective, criterion. Nonetheless, some MSS can be judged as superior to others by rather objective criteria—few harmonizations, fewer stylistic improvements, and so forth. If you wish to read further about many of the more significant witnesses and their relative quality, you should find either Metzger's or the Alands' handbook to be helpful.

You may find it helpful at this point to rearrange the external evidence in the form of a diagram that will give you an immediate visual display of supporting witnesses by date and text type. The easiest way to do this is to draw four vertical columns on a sheet of paper for the four text types (Egyptian, Western, Caesarean, Byzantine), intersected by six horizontal lines for the centuries (second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth-tenth, eleventh-sixteenth). Then simply put the external evidence in the appropriate boxes, one display for each variant.

When these criteria are applied to the first variation unit in John 3:15, variants 1 and 4 emerge as the most viable options, with variant 1 slightly favored, mostly because of the well-established high quality of P75 and B, and because the earliest evidence for variant 4 is in

the "Western" tradition, which is notorious for harmonizations (in this case to v. 16).

In the case of the second variation unit the evidence is weighted overwhelmingly in favor of the shorter reading (lacking μή άπόλη-ταυ άλλ’) as the original text.

As important as this evidence is, however, it is not in itself decisive; so one needs to move on to the question of internal evidence.

2.4. Evaluate each of the variants on the basis of the author's style and vocabulary (the criterion of intrinsic probability).

This is the most subjective of all the criteria and therefore must be used with caution. It also has more limited applicability, because often two or more variants may conform to an author's style. Nonetheless, this is frequently a very important criterion—in several ways.

First, in a somewhat negative way the criterion of author's usage can be used to eliminate or at least to suggest as highly suspect one or more of the variants, thus narrowing the field of options. Second, sometimes it can be the decisive criterion when all other criteria seem to lead to a stalemate. Third, it can support other criteria when it cannot be decisive in itself.

Let us see how this criterion applies to the first variation unit in John 3:15. First, you must ask the question, Which of the variants best comports with Johannine style? In this case, and often in others, you should also be aware of which of the options is better or worse Greek. There are several ways to find this out: (1) Several matters of usage can be discovered by reading the BDAG Lexicon (see II.4) or by checking one of the advanced grammars (see II.3.2.1). (2) The fourth volume of Moulton and Howard's Grammar, Nigel Turner on Style (II.3.2.1), has much useful information on these matters. (3) Most important, you can discover much on your own by a careful use of your concordance (see the bibliographic note following II.4.3). (4) For those who use computers, the ultimate tool in this regard is the software program called Gramcord (see the bibliographic entry in IV.6).

In this case, by checking out πιστεύω (believe) in your concordance, you will discover that in John's Gospel this verb takes as its object either αΰτω (him) or εις αυτόν (into him) but never the other

three options. You should also note that έπ’ αύτω or επ’ αυτόν is used by other NT writers. A look at the BDAG Lexicon or at one of the advanced grammars will reveal similar patterns, namely, that πιστεύω may take as its object either αύτω (him) or one of the prepositional forms εις αύτόν (into him), έπ’ αύτω (on him), or έπ’ αύτόν (on him), but that έν αύτω (in him) is rare.

On the basis of Johannine style, therefore, one may properly rule out έπ’ αύτω and έπ’ αύτόν. Those seem to be corruptions of one of the other two. But what shall we do with έν αύτω, which ordinarily is never used as the object of πιστεύω (and never so by John) but which has the best external evidence? The answer must be that it is not the object of πιστεύω at all but goes with the following έχη ζωήν αιώνιον (might have eternal life), designating the source or basis of eternal life. A check with the concordance reveals that such usage is Johannine, since a similar expression, in this word order, is found in 5:39 (cf. 16:33).

Thus we have with this criterion narrowed down the options to ό πιστεύων εις αύτόν (the one who believes in him) or έν αύτω έχη ζωήν αιώνιον (in him may have eternal life), both of which are Johannine.

It should be noted, finally, that this criterion is not always useful in making textual choices. For example, the words μή άπόληται άλλ’ (should not perish but) are obviously Johannine, since they occur in v. 16. But their absence in v. 15 would be equally Johannine.

2.5. Evaluate each of the variants by the criteria of transcriptional probability.

These criteria have to do with the kinds of mistakes or changes copyists are most likely to have made to the text, given that one of the variants is the original. They are conveniently displayed in Metzger's Textual Commentary, pp. 12*-13*. You should note two things about them: (1) Not all the criteria are applicable at the same time for any given unit of variation. (2) The overarching rule is this: The reading that best explains how the others came into existence is to be preferred as the original text.

By these criteria we may note that the variant έν αύτω now emerges rather clearly as the original text in John 3:15.

First, it is the more difficult reading. That is, given the high frequency of πιοτεύειν εις αυτόν (to believe in him) in John, it is easy to see how a copyist would have missed the fact that εν αύτω (in him) belongs with έχη ζωήν αιώνιον (might have eternal life) and, also recognizing that 6 πιοτεύων εν αύτω was not normal Greek, would have changed έν αύτω to the more common form. The fact that ό πιστεύ-ων έν αύτω would be such poor Greek usage also explains the emergence of επ’ αύτω and in’ αύτόν. That is, both of these are "corrections" that witness to an original text with έν αύτω, not εις αύτόν.

Conversely, there is no good explanation why a scribe would have changed εις αύτόν to any of the other forms, since ό πιοτεύων εις αύ-τόν makes perfectly good sense and since no one seems to have made this change elsewhere in John.

Second, the variant ε’ις αύτόν can also be explained as a harmonization to v. 16. This would especially be true in those instances where the words μή άπόληται άλλ’ were also assimilated from v. 16 so that the prepositional phrase could belong only with ό πιοτεύων and was no longer available to go with έχη ζωήν αΙώνιον. Again there seems to be no good explanation, given the firm text in v. 16, for why anyone would have changed ε’ις αύτόν εχη μή άπόληται άλλ’ to read έν αύτω, especially with the inherent difficulties it presents when it immediately follows πιοτεύων.

But one can explain how an author would have done it. He did not even think of έν αύτφ as following ό πιοτεύων. Once he had written ό πιοτεύων (the one who believes), he moved on to emphasize that in the Son of Man the believer will have eternal life. Thus he wrote έν αύτω following ό πιοτεύων but never intended it to go with that verb form. But later scribes missed John's point and "corrected" the text accordingly.

You should note here how all three sets of criteria (external evidence, intrinsic probability, and transcriptional probability) have converged to give us the original text. In your exegesis paper, the addition of μή άπόληται άλλ’ may be relegated to a footnote that reads something like this: "The Old Latin MSS, followed by the later majority of Greek witnesses, add μή άπόληται άλλ’, as an assimilation to v. 16. The addition could only have happened in Greek after έν αύτω had been changed to εις αύτόν." By contrast, you would need to discuss the έν αύτώ/ εις αύτόν interchange in some measure because the very meaning of the text is affected by it.

One should note, finally, that after much practice you can feel confidence in making your own textual choices. That is, you must not feel that the text of NA27 is always correct and therefore is the text you must exegete.

An example might be the variation unit in John 3:13. Briefly, you will note that the external evidence does favor the text of NA27. But at II.2.4 one must take the point of view of a second-century scribe. Which is more likely? That he had a text like NA27 and added b ων εν τω ούρανω (the one who is in heaven) for christological reasons? (If so, one might further ask what could have impelled him to do so right at this point.) Or that he had those words in his text but understood v. 13 to be the words of Jesus in dialogue with Nicodemus? If the latter is the case, the scribe must have wondered: How could the One speaking to Nicodemus also have said the Son of Man was at that time ό ων εν τω ούρανω (the one who is in heaven)? So he simply omitted those words from his copy. The minority of the UBS4 committee thought this to be the more likely option. You will have to make up your own mind. But you can see from this how integral to exegesis the questions of textual criticism are.

Section 11.3

second kind of exegetical decision that must be made for any given passage concerns grammar (see Steps 4 and 6 in the exeget-ical process, outlined in Chapter I). Grammar has to do with all the basic elements for understanding the relationships of words and word groupings in a language. It consists of morphology (the systematic analysis of classes and structures of words—inflections of nouns, conjugations of verbs, etc.) and syntax (the arrangements and interrelationships of words in larger constructions). Many of the basic syntactical decisions need to have been made in constructing the sentence-flow schematic (Section 1, above). This section is designed to help you with grammatical questions that arise on the basis of morphology.

As suggested in Chapter I, you should ideally decide the grammar for everything in your passage; however, in your paper you will discuss only those matters that have significance for the meaning of the passage. Hence one of the problems in presenting the material in this section is, on the one hand, to highlight the need for solid grammatical analysis but, on the other hand, not to leave the impression—as is so often done—that exegesis consists basically of deciding between grammatical options and lexical nuances. It does make a difference to understanding whether Paul intended ζηλοΰτε in 1 Cor. 12:31 to be an imperative (desire earnestly), with a consecutive δέ (so now), or an indicative (you are earnestly desiring), with an adversative δέ (but). It also will make a difference in translation whether the participle υποτιθέμενος (pointing out) in 1 Tim. 4:6 is conditional (TNIV, RSV) or attendant circumstance (NEB), but in terms of Paul's intent, the differences are so slight as not even to receive attention in most commentaries. So part of the need here is to learn to become sensitive to what has exegetical significance and what does not.

The problems are further complicated by the fact that the users of this book will have varying degrees of expertise with the Greek language. This section is written with those in mind who have had some beginning Greek and who thus feel somewhat at home with the basic elements of grammar, but who are still mystified by much of the terminology and many of the nuances. The steps suggested here, therefore, begin at an elementary level and aim at helping you use the tools, and finally work toward your being able to discriminate between what has significance and what does not.

3.1. Display the grammatical informationfor the words in your text on a grammatical information sheet.

A grammatical information sheet should have five columns: the biblical reference, the "text form" (the word as it appears in the text itself), the lexical form (as found in BDAG), the grammatical description (e.g., tense, voice, mood, person, number), and an explanation of the meaning and/or usage (e.g., subjective genitive, infinitive of indirect discourse). At the most elementary level, you may find it useful to chart every word in your text (less the article). As your Greek improves, you will do a lot of this automatically while you are at exegetical Step 3 (the provisional translation; see 1.3.1). But you still may wish to use the grammatical information sheet—for several reasons: (1) to retain any lexical or grammatical information discovered by consulting the secondary sources; (2) to isolate those words that need some careful decision making; (3) to serve as a check sheet at the time of writing, in order to make sure you have included all the pertinent data; (4) to serve as a place for speculation or debate over matters of usage.

In the column "use/meaning," you should give the following information:

for nouns/pronouns: case function (e.g., dative of time, subjective genitive); also antecedent of pronoun for finite verbs: significance of tense, voice, mood for infinitives: type/usage (e.g., complementary, indirect discourse) for participles: type/usage

attributive: usage (adjective, substantive, etc.) supplementary: the verb it supplements circumstantial: temporal, causal, attendant circumstance, etc. for adjectives: the word it modifies for adverbs: the word it modifies

for conjunctions: type (coordinate, adversative, time, cause, etc.) for particles: the nuance it adds to the sentence

3.2. Become acquainted with some basic grammars and other grammatical aids.

For you to address some of the "usage" matters in 3.1, as well as to make some of the decisions in 3.3 and 3.4, you will need to have a good working acquaintance with the tools.

Grammatical helps may be divided roughly into three categories: (1) intermediate grammars, (2) advanced grammars, (3) other grammatical aids. We begin with the intermediate grammars, because these are the tools you use as a student, and they are most likely the ones you will use throughout your life as a pastor.

3.2.1. Intermediate Grammars

The purpose of the intermediate grammar is to systematize and explain what the student has learned in his or her introductory grammar. Pride of place now goes to:

Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1996).

This is easily the most important grammar now in use for exegetical work. The author gives numerous examples (and one must remember that he is also an interpreter) of how various syntactical matters affect one's understanding of the text. If you use Greek at all, this is the grammar to purchase. But you may also find the abbreviated version to be helpful for quick reference:

Daniel B. Wallace, The Basics of New Testament Syntax: An Intermediate Greek Grammar (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 2000).

Other grammars in this category include:

James A. Brooks and Carlton L. Winbery, Syntax of New Testament Greek (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1979).

Robert W. Funk, A Beginning-Intermediate Grammar of Hellenistic Greek, 2d ed., 3 vols. (Missoula, Mont.: Scholars Press, 1973).

A. T. Robertson and W. H. Davis, A New Short Grammar of the Greek Testament, 10th ed. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1933; reprint, Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1977).

Students tend to find Brooks and Winbery an especially helpful tool.

3.2.2. Advanced (Reference) Grammars

These grammars are the ones used by the scholars. They are sometimes not of much help to the student because they assume a great deal of knowledge both of grammar in general and of the Greek language in particular. But the student must become acquainted with them, not only in the hope of using them someday on a regular basis but also because they will be referred to often in the literature.

Here pride of place goes to:

Friedrich Blass and Albert Debrunner, A Greek Grammar of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, trans. and rev. Robert W. Funk (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961). [JAF 203]

The other major grammar is:

James H. Moulton and W. F. Howard, A Grammar of New Testament Greek (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark): vol. 1, Prolegomena, by Moulton, 3d. ed., 1908; vol. 2, Accidence and Word-Formation, by Moulton and Howard, 1929; vol. 3, Syntax, by Nigel Turner, 1963; vol. 4, Style, by Turner, 1976. [JAF 208]

An older reference grammar, which is often wordy and cumbersome but which students will find useful because so much is explained, is:

A. T. Robertson, A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research, 4th ed. (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1934). [JAF 209]

3.2.3. Other Grammatical Aids

The books in this category do not purport to be comprehensive grammars, but each has usefulness in its own way.

For the analysis of Greek verbs, one will find a great deal of help in:

Ernest D. Burton, Syntax of the Moods and Tenses in New Testament Greek, 3d ed. (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1898; reprint, Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1976).

Two especially useful books that come under the category of "idiom books," offering helpful insight into any number of Greek usages, are:

C. F. D. Moule, An Idiom Book of New Testament Greek, 2d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963). [JAF 207]

Max Zerwick, Biblical Greek Illustrated by Examples (Rome: Biblical Institute Press, 1963). [JAF 212]

For the analysis of genitives on the basis of linguistics rather than classical grammar, you will find an enormous amount of helpful information in:

John Beekman and John Callow, Translating the Word of God (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1974), pp. 249-66.

For a particularly helpful analysis of prepositions and their relation to exegesis and theology in the NT, see:

Murray J. Harris, "Appendix: Prepositions and Theology in the Greek New Testament," in The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, ed. Colin Brown (Grand Rapids: Zon-dervan Publishing House, 1978), vol. 3, pp. 1171-1215.

3.3. Isolate the words and clauses that require grammatical decisions between two or more options.

This is a step beyond 3.1, in that most words are straightforward in their respective sentences and seldom require any kind of exeget-ical decision based on grammar. As with other matters, such discernment is learned by much practice. Nonetheless, grammatical decisions must frequently be made. Such decisions, which will make an exegetical difference, are of five kinds.

3.3.1. Determine the "case and why" of nouns and pronouns.

The decisions here most frequently involve genitives and datives. One should regularly try to determine the usage when these two cases occur. This is especially true of genitives, because they are so often translated into English by the ambiguous "of." Notice, for example, the considerable difference in 1 Thess. 1:3 between the NRSV's "steadfastness of hope" (whatever that could possibly mean) and the TNIV's more helpful "endurance inspired by hope" (cf. Rom. 12:20, "coals of fire" [KJV], with "burning coals" [NRSV, TNIV]; cf. Heb. 1:3, "the word of his power" [KJV], "his word of power" [RSV], with "his powerful word" [NRSV, TNIV]). On these matters you will find both Wallace and Brooks-Winbery to be helpful.

Frequently such choices considerably affect one's understanding of the text; and opinions will differ. Paul's (apparently varied) use of "the righteousness of God" (= the righteousness that God gives? or the righteousness God has in himself and his actions?) is a well-known case in point. Another example is the εις κρίμα τού διαβόλου in 1 Tim. 3:6. Does this mean "a judgment contrived by the devil" (NEB, now changed in the REB) or "the same judgment as the devil" (TNIV)?

3.3.2. Determine the tense (Aktionsart), voice, and mood of verb forms.

The examples here are legion. Is βιάζεται in Matt. 11:12 middle ("has been forcefully advancing" [NIV]) or passive ("has been subjected to violence" [TNIV, NEB])? Does Paul "mean" anything by the two present imperatives (the first a prohibition) in Eph. 5:18? Does the αποστερείτε in 1 Cor. 7:5 have the force of "stop abusing one another (in this matter)"?

Here in particular, however, one must be careful of overexegeting. For example, in the subjunctive, imperative, and infinitive moods, the common "tense" in Greek is the aorist. Therefore, an author seldom "means" anything by such usage. Nor does that necessarily imply that using the present does "mean" something (e.g., πιστεΰητε [that you might believe] in John 20:31). But that, of course, is what exegesis is all about at this point—what are the possibilities, and what most likely did the author intend by this usage (if anything at all)? Deciding that there is no special meaning to be found in some usages is also part of the exegetical process.

3.3.3. Decide the force or meaning of the conjunctive signals (conjunctions and particles).

Here is an area that is commonly overlooked by students, but one that is frequently of considerable importance in understanding a text. One of the more famous examples is the 81 mi . . . μάλλον in 1 Cor. 7:21 (= "if indeed"? or "even if"?). In 1 Thess. 1:5, as another exam-pie, one must decide whether the ότι in v. 5 is causal or epexegetical (appositional)—again, note the difference between TNIV and NEB (the latter changed in the REB).

It is especially important that you do not too quickly go over the common δέ (but, now, and). Its frequency as a consecutive or resumptive connective causes one sometimes to miss its clearly— and significantly—adversative force in such passages as 1 Tim. 2:15 or 1 Thess. 5:21.

3.3.4. Decide the force or nuances of prepositions.

Here especially, one must avoid the frequent trap of creating a "theology of prepositions," as though a theology of the atonement could be eked out of the difference between ύπέρ (on behalf of) and περί (concerning). But again, there are times when the force of the prepositional phrases makes a considerable difference in the meaning of a whole sentence. This is especially true, for example, of the έν (in/by) and εις (into/so as to) in 1 Cor. 12:13 or the διά (through/in the circumstance of) in 1 Tim. 2:15.

3.3.5. Determine the relationship of circumstantial (adverbial) participles and infinitives to the sentence.

Again, one must avoid overexegeting. Sometimes, of course, the adverbial sense of the participle is clear from the sentence and its context (e.g., the clearly concessive force of ζώσα [even though she lives] in 1 Tim. 5:6). As noted earlier, however, although decisions here may frequently make a difference in translation, they do not always affect the meaning. The reason for this, as Robertson correctly argues (Grammar, p. 1124), is that the basic intent of such a participle is attendant circumstance. If the author's concern had been cause, condition, or concession, he had unambiguous ways of expressing that. So, while it is useful to train oneself to think what nuance might be involved, one needs also to remember not to make too much of such decisions.

The question of how one goes about making the decisions necessary at this step is very closely related to what was said about the placement of certain modifiers in II.1.1.6 (example 2). Basically the steps are four:

a. Be aware of the options (what we have been talking about right along).

b. Consult the grammars.

c. Check out the author's usage elsewhere (here you will want to make large use of your concordance).

d. Determine which option finally makes the best sense in the present context.

3.4. Determine which grammatical decisions need discussion in your paper.

This step "calls for a mind with wisdom," because it will be one of the things that makes a difference between a superior and a passable paper. The clear determining factor is: Discuss only those grammatical matters that make a difference in one's understanding of the text. Some items simply do not carry the same weight as others and may be safely relegated to a footnote. But when the grammatical questions are crucial to the meaning of the whole text (as with many of the above examples); or when they make a significant difference in perspective (e.g., Are the occurrences of διαβόλου [the devil] in 1 Tim. 3:6 and 7 subjective or objective?); or when they add to one's understanding of the flow of the argument as a whole (e.g., δέ and διά in 1 Tim. 2:15), then such discussion should be found in the body of the paper.

Section 11.4

n any piece of literature, words are the basic building blocks for conveying meaning. In exegesis it is especially important to remember that words function in a context. Therefore, although any given word may have a broad or narrow range of meaning, the aim of word study in exegesis is to try to understand as precisely as possible what the author was trying to convey by his use of this word in this context. Thus, for example, you cannot legitimately do a word study of σαρξ (flesh); you can only do a word study of σαρξ in 1 Cor. 5:5 or in 2 Cor. 5:16, and so on.

The purpose of this section is (1) to help you learn to isolate the words that need special study, (2) to lead you through the steps of such study, and (3) to help you use more fully and efficiently the two basic tools for NT word study. Before going through these steps, however, it is important to raise two cautions.

First, avoid the danger of becoming "derivation happy." To put it simply, to know the etymology, or root, of a word, however interesting it may be, almost never tells us anything about its meaning in a given context. For example, the word εκκλησία (church) indeed derives from έκ + καλέω ("to call out from"), but by the time of the NT that is not within its range of meanings. And in any case, NT usage had already been determined by its prior use in the LXX, where it was consistently used to translate the term "the congregation" of Israel. Therefore, it does not mean "the called-out ones" in any NT context.

Second, avoid the danger of overanalysis. It is possible to make too much of the use of specific words in a context. Biblical authors, like ourselves, did not always carefully choose all their words because they were fraught with significance. Sometimes words were chosen simply because they were already available to the author with his intended meaning. Furthermore, words were sometimes chosen for the sake of variety (e.g., John's interchange of αγαπάω [love] and φιλέω [love]), because of wordplay, or because of alliteration or other stylistically pleasing reasons.

Nonetheless, the proper understanding of many passages depends on a careful analysis of words. Such analysis consists of three steps.

4.1. Isolate the significant words in your passage that need special study.

To determine which are "the significant words," you may find the following guidelines helpful:

4.1.1. Make a note of those words known beforehand or recognizable by context to be theologically loaded. Do not necessarily assume you already know the meaning of ελπίς (hope), δικαιοσύνη (righteousness), αγάπη (love), χάρις (grace), and so forth. For example, what does "hope" mean in Col. 1:27, or χάρις in 2 Cor. 1:15, or δικαιοσύνη in 1 Cor. 1:30? In these cases in particular, it is important to know not only the word in general but also the context of the passage in particular.

4.1.2. Note any words that will clearly make a difference in the meaning of the passage but seem to be ambiguous or unclear, such as παρθένων (virgins) in 1 Cor. 7:25-38, σκεύος (vessel = wife? body? sexual organ?) in 1 Thess. 4:4, διάκονος (minister/servant/deacon) in Rom. 16:1, or the idiom γυναικός άπτεσθαι (lit., to touch a woman = to have sexual relations) in 1 Cor. 7:1.

4.1.3. Note any words that are repeated or that emerge as motifs in a section or paragraph, such as οίκοδομέω (edify) in 1 Cor. 14, or

άρχοντες (rulers) in 1 Cor. 2:6-8, or καυχάομαι (boast) in 1 Cor. 1:26-31.

4.1.4. Be alert for words that may have more significance in the context than might at first appear. For example, does άτάκτως in 2 Thess. 3:6 mean only to be passively lazy, or does it perhaps mean to be disorderly? Does κοπιάω in Rom. 16:6 and 12 mean simply "to labor," or has it become for Paul a semitechnical term for the ministry of the gospel?

4.2. Establish the range of meanings for a significant word in its present context.

Basically, this involves four possible areas of investigation. But note well that words vary, both in importance and usage, so that not all four areas will need to be investigated for every word. One must, however, be alert to the possibilities in every case. Note also, therefore, that the order in which they are investigated may vary.

4.2.1. Determine the possible usefulness of establishing the history of the word. This first step is "vertical." Here you are trying to establish the use of a word prior to its appearance in your NT document. How was the word used in the past? How far back does it go in the history of the language? Does it change meanings as it moves from the classical to the Hellenistic period? Did it have different meanings in Greco-Roman and Jewish contexts?

The opening caution must be brought forward here. This part of the investigation is to give you a "feel" for the word and how it was used historically in the language; it may or may not help you understand the word in its present NT context.

Most of this information is available in your BDAG Lexicon. In the examples that follow, I will show you how to get the most possible use out of BDAG.

The next three steps are "horizontal," that is, you are trying to learn as much as you can about the meaning of your word in roughly contemporary literature or in some of the earlier literature. You might think of these "steps" in terms of concentric circles, in which you move (in terms of NT usage) from the outermost circle of pagan

literary and nonliterary texts (the papyri), to Jewish literary texts (Philo, Josephus), to Jewish biblical texts (LXX, the Pseudepigrapha), to other NT usage, to other usage by the same author, to the immediate context itself.

4.2.2. Determine the range of meanings found in the Greco-Roman and Jewish world contemporary with the NT. What meaning(s) does the word have in what different kinds of Greco-Roman literary texts? Do the nonliterary texts add any nuances not found in the literary texts? Is the word found in Philo or Josephus, and with what mean-ing(s)? Was it used by the LXX translators? If so, with what mean-ing(s)?

4.2.3. Determine whether, and how, the word is used elsewhere in the NT. If you are working on a word from a paragraph in Paul, is he the most frequent user of the word in the NT? Does it have similar or distinctive nuances when used by one or more other NT writers?

4.2.4. Determine the author's usage(s) elsewhere in his writings. What is the range of meanings in this author himself? Are any of his usages unique to the NT? Does he elsewhere use other words to express this or similar ideas?

4.3. Analyze the context carefully to determine which of the range of meanings is the most likely in the passage you are exegeting.

Are there clues in the context that help to narrow the choices? For example, does the author use it in conjunction with, or in contrast to, other words in a way similar to other contexts? Does the argument itself seem to demand one usage over against others?

A Bibliographic Note

To do the work required in Step 4.2, you will need to have a good understanding of several tools. It should be noted, however, that in most cases you can learn much about your word(s) by the creative use of two basic tools: a lexicon and a concordance.

For a lexicon you should use the following:

Walter Bauer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (BDAG), 3d ed., ed. Frederick W. Danker (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000). [JAF 173]

This third edition of Bauer is a considerable improvement over the first two editions—so much so that if you have not yet purchased a lexicon, this one is a must (rather than a secondhand second edition, for example). Based on Bauer's sixth German edition, and keeping all its best features, under the editorship of Professor Danker "Bauer" has become much more user friendly. If you do own the second (or first) edition(s), however, you will be able to follow the present discussion, because most of the pertinent information is there—even though it has been thoroughly rearranged. In any case, one look at the example on p. 86 will show you how much easier it now is to find the necessary data as you work through an entry.

For a concordance, use either of the following:

H. Bachmann and H. Slaby (eds.), Computer-Konkordanz zum Novum Testamentum Graece von Nestle-Aland, 26. Auflage, und zum Greek New Testament, 3d ed. (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1980).

William F. Moulton and A. S. Geden, A Concordance to the Greek Testament according to the Texts of Westcott and Hort, Tischendorf and the English Revisers, 5th rev. ed. Η. K. Moulton (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1978). [JAF 228]

Unfortunately, these are both expensive volumes. But one or the other should be used in exegesis, because they are true concordances (that is, they supply enough of the text for each word to help the user see the word in its context). The Computer-Konkordanz is to be preferred because (1) it is based on NA26; (2) it gives a total of NT occurrences for each word; and (3) it repeats the whole text if a word occurs more than once in a verse. Moulton-Geden, by contrast, has the added usefulness of coding certain special uses of a word in the NT.

If you have access to a good library, you may wish to use the ultimate, but prohibitively expensive, concordance:

Kurt Aland (ed.), Vollstdndige Konkordanz zum griechischen Neuen Testament, 2 vols. (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1975,1983). [JAF 226]

This concordance gives the occurrences of a word in NA26 as well as in the textual apparatus and the Textus Receptus. It also has coded special usages. Volume 2 gives two lists of word statistics: the num-her of uses for each word in each NT book, and a breakdown of the number of occurrences for each form of the word in the NT.

In the following examples you will have opportunity to learn how to use these, as well as several other, lexical tools.

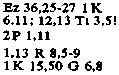

Example 1: How to Use BDAG

In 1 Cor. 2:6-8, Paul speaks of the άρχοντες (rulers) of this age, who are coming to nothing (v. 6) and who crucified the Lord of glory (v. 8). The question is: To whom is Paul referring, the earthly leaders who were responsible for Christ's death or the demonic powers who are seen as ultimately responsible for it (or a combination of both— demonic powers working through earthly leaders)?

Let us begin our investigation by carefully working our way through BDAG (see the facsimile on p. 86). This example was chosen because it also helps you see that BDAG is a secondary source; that is, a lexicographer is an interpreter as well as a provider of the data. In this instance I happen to disagree with BDAG, but it will be equally clear that one cannot get along without it.

[Note for English readers: For those who do not know Greek but have learned the alphabet and can look up words, a couple of additional resources will help you get into the BDAG Lexicon in two easy steps:

[1. You need first to locate the Greek word that needs to be examined. There are two ways to go about this. The best way is to work from a Greek-English interlinear:

J. D. Douglas (ed.), The New Greek-English Interlinear New Testament (Wheaton, 111.: Tyndale House Publishers, 1990).

Or you may prefer the more circuitous route (assuming the KJV) of using the coding system in

James Strong, Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1980).

If you use Strong, you also cut out the next step, since the "lexical" form is what is given in his "Dictionary" section. For help in using Strong, see Cyril J. Barber, Introduction to Theological Research (Chicago: Moody Press, 1982), pp. 72-75.

[2. If you use the interlinear, you will need to take the second step of finding the "lexical form" of the word (i.e., the form found in the lexicon itself). To do this you should use one of the following:

Harold K. Moulton (ed.), The Analytical Greek Lexicon Revised (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1978).

Barbara Friberg and Timothy Friberg, Analytical Concordance of the Greek New Testament—Lexical Focus (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1981).

These two tools basically offer the same kind of help. Moulton lists in alphabetical order every word as it appears in the Greek NT, with the corresponding lexical form and its grammatical description. The Fribergs do the same thing, but in the actual canonical order. The latter is thus keyed to help you find words at the very point where you are working in the New Testament itself.

[Thus by looking up άρχοντες you will discover that it is the nominative plural of άρχων, which is the word you will look up in the lexicon.]

What follows is an attempt to take you by the hand and lead you through the entry in BDAG. Thus you will want continually to refer to the entry in BDAG itself, which has been included here for your convenience. Before going through the entry in detail, however, you should take the time to become familiar with the lists of abbreviations found in BDAG on pp. xxxi-lxxix, since all entries are full of (necessary) abbreviations so as to keep the entries as brief as possible. The first list (pp. xxxi-xxxiii) will also remind you that this is a lexicon for both the New Testament and "other early Christian literature." But one of the significant differences between this and former editions is that NT references are now given in bold for easy sighting.

Let's begin by noting the overall format of the entry, which will be similar for all words that have at least a twofold range of meanings. The first paragraph always gives the two basic lexical data: (1) the entry itself (which [a] in the case of nouns is followed by the genitive

αρχών, οντος, ό (Aeschyl., Hdt.+) actually ptc. of άρχω, used as subst.: one who is in a position of leadership, esp. in a civic capacity.

O one who has eminence in a ruling capacity, ruler, lord, prince—© of earthly figures, 01 ά. των εθνών Mt 20:25; cp. B 9:3 (Is 1:10); oi a. the rulers Ac 4:26 (Ps 2:2). W. διχαστής of Moses (in quot. of Ex 2:14): 7:27,35 and 1 Cl 4:10.

® of Christ ό ά. τ. βασιλέων τ. γης the ruler of the kings of the earth Rv 1:5;

© of transcendent figures. Evil spirits (Kephal. I p. 50, 22; 24; 51, 25 al.), whose hierarchies resembled human polit. institutions. The devil is ά. τ. δαιμόνιων Mt 9:34; 12:24; Mk 3:22; Lk 11:15 (s. Βεελζεβούλ.—Porphyr. [in Eus., PE 4, 22, 15] names Sarapis and Hecate as τούς άρχοντας τ. πονηρών δαιμόνων) 0Γά. του κόσμου τούτου J 12:31; 14:30; 16:11; ά. καιρού τού νϋν τής άνομίας Β 18:2; ό ά. τού αΐώνος τούτου (Orig., C. Cels. 8, 13,13) IEph 17:1; 19:1; IMg 1:2; ITr4:2; IRo 7:1; IPhld 6:2. (Cp. Ascls 1, 3; 10, 29.) At AcPICor 2, 11 the ed. of PBodmer X suggests on the basis of a Latin version (s. ZNW 44,1952-53,66-76) that the following words be supplied between πολλοΐς and θέλων είναι: [ό γάρ άρχων άδικος ών| (καί) θεός] (lat.: nam quia injustus princeps deus volens esse) [theprince (of this world) being unjust] and desiring to be [god] (s. ASchlatter, D. Evglst. Joh. 1930, 27If). Many would also class the άρχοντες τού αΐώνος τούτου 1 Cor 2:6-8 in this category (so from Origen to H-DWendland ad 10c., but for possible classification under mng. 2 s. TLing, ET 68, ’56/57, 26; WBoyd, ibid. 68, ’57/58,158). ό πονηρός ά. Β 4:13; ό άδικος ά. ΜΡ01 19:2 (cp. ό άρχων τ. πλάνης TestSim 2:7, TestJud 19:4). ό ά. τής εξουσίας τού άέρος Eph 2:2 (s. άήρ, end). W. άγγελος as a messenger of God and representative of the spirit world (Por-phyr., Ep. ad Aneb. [s. άρχάγγελος] c. 10) Dg 7:2; οί ά. ορατοί τε καί άόρατοι the visible and invisible rulers ISm 6:1.

Θ gener. one who has administrative authority, leader, of-ficial(so loanw. in rabb.) Ro 13:3; Tit 1:9 v.l. (cp. PsSol 17:36). For 1 Cor 2:6-8 s. lb above.