Intolerance and the Soviets: A Historical Investigation

Tracing lines of influence in film history is one of the most popular endeavours among film scholars; it is also one of the most treacherous. The appearance of similar styles or conventions among different schools of film often invites premature conclusions about direct lines of descent. The historian, therefore, must penetrate below such surface observations to identify the complexities and contradictions of historical continuity if we are truly to understand the links between one cinematic movement and another.

Historians agree that the most influential early film-maker was D.W. Griffith and that among his most precocious students were the Soviet directors of the 1920s. Furthermore, Intolerance is singled out as the most conspicuous link between Griffith and the Soviets, with the explanation that the radical editing style of Griffith’s 1916 feature was instrumental in shaping the montage school of film which culminated in the USSR in the middle and late 1920s. Intolerance was admired in the Soviet Union. It was reputedly studied in the Moscow Film Institute for the possibilities of montage and ‘agitational’ cinema [agitfil’m], and leading Soviet directors, including Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Kuleshov, acknowledged a debt to Griffith in their writings.1

Such evidence would seem to support the assumption that Griffith and Intolerance were of paramount importance to the Soviets. Griffith’s most loyal partisans attribute many of the salient characteristics of Soviet cinema to Griffith’s legacy.2 But more balanced studies argue that Intolerance was actually one of several sources for the Soviets and that the Soviet montage aesthetic originated in Russian avant-garde art, theatre and literature.3 An examination of the circumstances and ramifications of the distribution of Intolerance in the USSR will considerably qualify our assumptions about Griffith’s supposed hold over the Soviets.

I

The Soviet directors of the early post-Revolutionary period were excited primarily by American films. These young artists dismissed the Russian cinema of the tsarist period, with its preponderance of love triangles and uneven literary adaptations, as hopelessly decadent. American adventure and mystery films–to which the Soviets attached the single genre label detektiv–captured the fancy of the Soviets. They admired the vitality and frenetic activity of these ‘naive’ films. Kuleshov noted of the detektiv that ‘the fundamental element of the plot is an intensity in the development of action, the dynamic of construction’.4 The Soviets hoped to adapt this energetic style into an aggressive, revolutionary cinema.

The Americans offered no more impressive example of dynamic cinema than Intolerance, and various incidents attest to its impact in the USSR; Pudovkin abandoned a scientific career for the cinema after watching the film;5 Intolerance was so popular that in 1921 the Petrograd Cinema Committee organised an extremely successful two-week run of the film to raise funds for victims of the Civil War famine;6 Soviet representatives reportedly even extended Griffith an invitation to work in the USSR.7

Nevertheless, other evidence indicates that we should not overestimate the film’s importance–particularly as a stylistic inspiration. It would be incorrect to assume that the idea of film montage for the Soviets originated with Intolerance. Rather, it seems that when the film was shown in the Soviet Union in 1919, it merely popularised a style already evolving in the hands of Soviet artists. Kuleshov claims he began to forge his seminal theories well before Intolerance appeared in the Soviet Union. His experiments which defined the ‘Kuleshov effect’ apparently began as early as 1917–18. In March 1918, several months before the Russian première of Intolerance, Kuleshov published his theoretical essay ‘The Art of Cinema’, in which he argued that editing constituted the fundamental feature of film art.8 Vertov writes that he worked out a rapid montage style in his early film The Battle of Tsaritsyn [Boi pod Tsaritsynom, 1919–20]. Intolerance played in Russia while he was still at work on the film, and the American picture helped acquaint audiences with the mode he sought to perfect: ‘After a short time there came Griffith’s film Intolerance. After that it was easier to speak.’9 Intolerance may have been less a source than a vindication for these innovators.

Russia’s familiarity with Griffith actually predated the Revolution. A number of Griffith’s early Biograph shorts circulated in tsarist Russia, and at least one served as the source for a Russian film. Yakov Protazanov used the story of Griffith’s The Lonely Villa for his Drama by Telephone [1914]. Protazanov’s tale concerns a young wife who discovers that bandits are trying to break into her home. She immediately telephones her absent husband for help but, as he desperately rushes home, the bandits break in and overpower the wife. Whereas Griffith specialised in the successful rescue, in the Russian version the husband arrives too late and discovers that his wife has been murdered. This is not the only change Protazanov makes. Anyone searching for an early link between Griffith’s cross-cutting device and Soviet montage must look elsewhere. Protazanov is not concerned with the rhythm or tension of the attempted rescue, and he does not exploit parallel editing. Rather he examines the psychological states of the characters during the crisis, the terror of the woman and the panic of the husband, and he employs an elaborate split-screen system which permits the audience simultaneously to compare the emotions of the husband, wife and culprits.10 The Russian artist, in borrowing Griffith’s tale, specifically rejects Griffith’s most famous stylistic contribution to the genre.

II

The familiar story that Intolerance first reached the USSR after it somehow slipped through an anti-Soviet blockade is apocryphal.11 In fact the film was imported well before the Revolution. When the Italian spectacle Cabiria scored a success in Russia in 1915, it was assumed that a potential audience for spectacles existed there, and the Italian Jacques Cibrario, who headed the Transatlantic film distribution firm, brought Intolerance into Russia in 1916.12 But, although Intolerance overshadowed Cabiria in size and splendour, it was quickly labelled too avant-garde for Russian movie audiences. No Russian exhibitor would agree to handle the film for fear that audiences would be confused by the four-part structure. Consequently, the film gathered dust on a shelf somewhere in Russia until after the Revolution. Not until 1918 did a special government decision clear the way for Intolerance to be shown commercially in the RSFSR.13

The première of Intolerance in Petrograd was a major cinema event for the Soviets. On 17 November 1918 the Petrograd Cinema Committee sponsored a special showing for an audience composed largely of government officials, including the Commissar for Enlightenment, Anatoli Lunacharsky.14 The 25 May 1919 Moscow première was part of an official celebration. The occasion was the first anniversary of so-called ‘Universal Military Training’, the government’s Civil War programme of training Red Army conscripts. Intolerance warranted a special closed showing at the prestigious Moscow movie theatre, the Artistic [Khudozhestvennyi].15

The Moscow première inspired an illuminating review in Izvestiya. The critic was impressed by the American film’s scope and technical virtues, and he noted that it might serve as a model for future Soviet productions. But he dismissed the content as ‘bourgeois’: the theme of reconciliation and ‘notorious tolerance’ failed to resolve the issues of class conflict in the modern story. He suggested that Intolerance might be reconstructed into a thoroughly ‘agitational’ film by ‘turning scenes around and changing titles’.16 His remarks identify the ideological reservations that Soviet cinephiles had about the film. The Soviets recognised that Intolerance was a humanist, even a somewhat leftist film. But it certainly was not a revolutionary film. For Soviet artists anxious to find a cinematic model which combined the dynamic style of the detektiv with the political content of the agitfil’m, Intolerance was close yet still very far. Intolerance had its militant moments– most notably the strike sequence–but its vague sentimental humanism left Griffith’s Soviet admirers cold.

The Izvestiya critic advocated the re-editing of the film for commercial release to give it a proper slant. It is difficult to determine the extent to which that was done. At least one account indicates that the Christ section was abridged in the public versions of the film.17 But there is reason to believe that the film was not completely altered by Soviet censors. The Soviet Union was entering the most eclectic years in all Russian intellectual history. Soviet artists were borrowing from numerous cultures and political systems, and as yet there was no Stalin or Zhdanov to enforce rigid conformity.18

More important, the Soviets employed a method of dealing with the ideological shortcomings of Intolerance that was far more ingenious and exciting than censorship. Intolerance was selected for presentation at the Congress of the Comintern in Petrograd in the summer of 1921. The Petrograd Cinema Committee undoubtedly hoped to impress the delegates with the potential of agitational cinema, but they were painfully aware of the film’s ideological deficiencies. They decided the occasion required them to ‘sharpen the class theme’ of the film while at the same time respecting the author’s original intentions.19 Their method was not to censor or cut parts of the film but rather to add to it. Nikolai Glebov-Putilovsky of the Petrograd Cinema Committee prepared a live, dramatised prologue which would amplify the anti-exploitation theme of the film’. The practice of adding Soviet propaganda to pre-Revolutionary works of art was common in the young socialist country. Soviet writer Demyan Bedny’s satirical poem at the base of a tsarist monument is another example of this method of ‘finishing’ a work of art.20 This operation transcends censorship. It respects the integrity of the original work while at the same time allowing the Soviets to make ideological improvements. Indeed, it rather resembles Meyerhold’s theatrical practice of staging classic and pre-Revolutionary plays in modern, Constructivist styles which were rich with propaganda.

It speaks well for Griffith that five years after Intolerance was made and almost two years after the nationalisation of the Soviet industry, the Soviets singled out this American film of dubious service to the Revolution for presentation at the Comintern Congress. Despite the shortage of celluloid, the Soviets did manage to prepare for the congress a series of documentary films on the work of the socialist government throughout the Soviet Union.21 But these apparently were rather pedestrian educational films. For an impressive example of agitfil’m, Intolerance may still have seemed the most palatable choice available. Also, the American epic undoubtedly had a more cosmopolitan appeal to the international audience than a strict diet of Soviet films would have had.22 In any event, the Cinema Committee was willing to sacrifice ideological purity to entertain and edify the socialist audience. The prologue would give the evening the proper dose of revolutionary spirit, and the movie would take care of itself.

The prologue allowed the Soviets to comment on the film and to add their own interpretations to certain scenes. The most glaring problem for the Soviets was the film’s insistent theme that history is cyclical. Intolerance advances the argument that the same cycles of intolerance and injustice simply recur in different historical dress. Basic impulses and human emotions, the fundamental forces in all human endeavours, are as consistent as the hand that rocks the cradle. Not surprisingly, the same dilemmas appear in epoch after epoch. This is hardly compatible with a Marxist, economic-determinist philosophy which considers history progressive and dialectical.

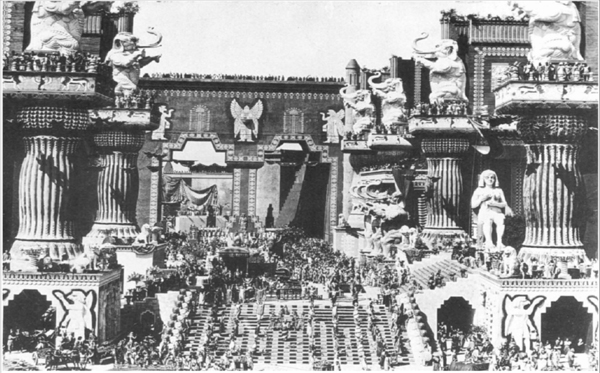

Figure 5 Intolerance [1916]: in honouring Griffith, the Soviets were compelled to criticise him.

The prologue goes about uniting Marx and Griffith with considerable finesse. Generally, the prologue seizes on certain vivid images of suffering and injustice in the film and casts these in a Marxist framework. The prologue opens with a call to those assembled:

Hear ye, hear ye, O people!… Hear, ye who have come hither: men and women, young and old–and behold! Beyond your life in the distant depths of history you will see a broad road that the human race has been following for thousands of years.23

Already it is clear that the delegates are in for a history class. The prologue emphatically proclaims that the lessons of Intolerance are the lessons of the past. The road is the central metaphor of the first half of the prologue, and on it can be seen the bitter teachings of history. A look down the road reveals countless examples of hardship in the lot of the common people. For example, the Girl is tossed by the evil hand of life into the mud and dust’.24

The road reveals something of a dialectic and a clear class conflict in the constant presence of opposites. The powerful and the weak, the exploiter and the exploited, are always present: ‘The ancient patrician and the plebeian, the king and his serf, Babylon and a simple settlement, love and hate, light and darkness’.25

The road metaphor disappears in the second half of the prologue and new imagery emerges. Now ancient mountains represent history. Out of these mountains of the past flow four small streams, the four tales of the film. The streams run in separate but parallel paths, suggesting the flux and turmoil of history –a counterpoint to the static, awesome mountains. We again see images of exploitation with the stories of Intolerance.

Millions and billions of riches, created by slave labour and legally accumulated by those who have seized control of the law: the factory owners, the governors, the public prosecutors, the emperors and their fine retinue of concubines and lackeys....

The French Court with its overdressed dolls and a gallows demanding a sacrifice. A smoke-filled episode of religious baseness from the stately priests and St Bartholomew’s Eve; a humble carpenter from Galilee; clean-handed Pilate and the wild instincts of the crowd, shouting, ‘Crucify Him! Crucify Him!’26

The prologue concludes with a promise of ultimate salvation from this history of cruelty. The four currents flow down the mountains unto a gentle plain where they merge into one stream. This is, in a sense, the synthesis, and it leads to the Soviet utopia’ In the beautiful valley of life’. The film shows the ugly lessons of the past, but for the future there is the promise of the Soviet system: from ‘the mire and slime and rottenness, from which we emerged with pain and torment towards the radiant Soviets: towards our temples of labour and liberty, through which we shall resurrect everything.’27 The prologue then ends with an affirmation and a rallying cry reminiscent of a varsity cheer:

The Soviets! The Soviets! –the earth hums.

The road of the Soviets–the Soviets are our salvation!!!28

By insisting that the stories of Intolerance represent some dreadful past, the Soviets could fit the film into a Marxist schema which promises a glorious future. The utopian vision in the prologue is no less naive than the film’s coda which calls for an era of brotherhood when prison walls will dissolve. Griffith invests his faith in an amorphous notion of brotherly love, and the Soviets celebrate an equally dubious confidence in the ability of socialism to eradicate all strife. The reconciliation between Marx and Griffith proved an ingenious, albeit tenuous one.

The prologue’s metaphor of the parallel streams originated in a playbill which accompanied the New York première of Intolerance:

Our theme is told in four little stories.

These stories begin like four currents, looked at from a hilltop. As they flow they grow nearer and nearer together, and faster and faster, ‘until in the end, in the last act, they mingle in one mighty river of expressed emotion’.

Then you see that, though they seem unlike, through all of them runs one thought, one theme.29

The metaphor here is restricted to describing the structure of the film itself. The four stories merge in the last reel of Intolerance through cross-cutting to create an emotional climax, ‘one mighty river of expressed emotion’. The Soviet prologue expands the metaphor into a historical one. Significantly, Eisenstein’s celebrated analysis of Intolerance in ‘Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today’, specifically cites the American playbill’s stream metaphor to analyse Griffith’s montage. He argues that Griffith’s film, contrary to the claim set out in the playbill, fails to achieve a true synthesis of tales. For him, Griffith’s montage is not truly dialectical, and he claims Intolerance remains a drama of comparisons–’a combination of four different stories, rather than a fusion of four phenomena into a single imagist generalisation’.30 The Soviet prologue subtly apologises for the ideological faults of Intolerance, and Eisenstein, who borrows the same metaphor from the same source, exposes what he considers the film’s formal problems. In honouring Griffith, the Soviets were compelled to criticise him.

This investigation of the early history of Intolerance in Russia reveals some of the hazards of too-easy assumptions of historical continuity. The evidence on the Soviet reception of Intolerance raises questions about the actual extent of the Soviet debt to Griffith that can only be resolved through meticulous stylistic comparisons of the work of the early Soviets and that of Griffith–not to mention such Griffith contemporaries as Ince, King, Feuillade and Gance. As present it seems clear that for all the attention the Soviets lavished on Intolerance, it was as important to them for its flaws as for its virtues.31

Prologue To Intolerance32

Hear ye, hear ye, O people!… Hear, ye who have come hither: men and women, young and old–and behold! Beyond your life in the distant depths of history you will see a broad road that the human race has been following for thousands of years. Behold!… There is plump Virtue: she feeds on nothing but human blood and her soul accepts nothing else. There are the Scribes and the Pharisees: those great lackeys, who make great show of their worship, who preen themselves on their merits and their morality even before God Himself, and everywhere there exist even today the agents of that great sacrificial Golgotha. You will see the Girl: a little slip of a girl, a dream, a flower tossed by the evil hand of life into the mud and dust, beneath the filthy carts of the bazaar where souls are bought and sold. Who has not trodden this road before you? The ancient patrician and the plebeian, the king and his serf, Babylon and a simple settlement, love and hate, light and darkness, the factory owner and the worker, sincerity and vile cunning, the height of civilisation and the depth of ignorance, grief and joy, war and peace, life itself and death, and, as a symbol of this great path, from the depths of history to the present day, the eternally rocking cradle over which the golden head of the mother is bent low.

What goes through your mind?

Four streams run down from the high old mountain of history: a picture of everyday life; medieval Jerusalem;33 France; and Babylon the magnificent.

Nightmarish wealth! Millions and billions of riches, created by slave labour and legally accumulated by those who have seized control of the law: the factory owners, the governors, the public prosecutors, the emperors and their fine retinue of concubines and lackeys. Those fleet-footed helmsmen…so obediently ready to oblige, devour with their masters the living human body and quench their thirst by drinking warm human blood.

The French Court with its overdressed dolls and a gallows demanding a sacrifice. A smoke-filled episode of religious baseness from the stately priests and St Bartholomew’s Eve; a humble carpenter from Galilee; clean-handed Pilate and the wild instincts of the crowd, shouting, ‘Crucify Him! Crucify Him!’

From the great old mountain that we call life the familiar flows before you and, merging into the rapid change of days, leads unexpectedly to the Soviets.

The ‘Soviets’ –that is our word.

What does it mean?

In the beautiful valley of life. At the foot of the mountain of history, creating nobody knows what. With passionate faith and the iron strength of conviction. Spread by the magic cauldron of the Revolution—the Soviets!

And, looking back across the threshold, remembering the road that mankind has taken, you record in a book and relate to others this last tale of our long enslavement. A tale of basest flattery and the trading of souls. Of the mire and slime and rottenness, from which we emerged with pain and torment towards the radiant Soviets: towards our temples of labour and liberty, through which we shall resurrect everything.

The Soviets! The Soviets! –the earth hums.

The road of the Soviets–the Soviets are our salvation!!!