Down to Earth: Aelita Relocated

Harmful literature is more useful than useful literature, for it is antientropic.

Yevgeni Zamyatin1

1

Has Anyone Actually Seen Aelita?

Aelita undeniably has a bad reputation. As the first, and for long the only, Soviet ‘spectacular’, promoted and launched like its Western equivalents, it naturally attracted suspicion in many quarters, despite (or perhaps ultimately because of) its resounding box-office success. Today the film itself remains as little seen as ever in ‘serious’ circles, and shares with the likes of High Treason and Things to Come a reputation of amounting to rather less than the undeniable impact of its science-fiction décor, stills of which, however, enliven many general cinema histories.2 These also appear in most surveys of science-fiction film and, especially, accounts of Russian avantgarde art, where their futuristic geometry provides an essential visual and plastic emblem of the era of heroic Soviet modernism.3 Yet the accompanying commentary often belittles, when it does not directly condemn, the film itself—and usually on the basis of a misleading plot summary.

Thus a self-perpetuating tradition has developed which effectively substitutes the paradigmatic quality of the stills for the implied failure of the film. Its apparent subject—a Soviet expedition to Mars which incites revolution against the ruling despots—simultaneously evokes the utopian aspiration of much early Soviet art while sounding risible; and the obviously theatrical stills, although more impressive than those from most ‘canonic’ Soviet classics, also seem to justify the scorn which the film originally attracted from advocates of a revolutionary new approach to cinema.4

However, to screen Aelita is to discover something rather different from the bête noire of Soviet montage cinema’s pioneers. Instead of the ‘photographed muddle of curves and triangles’ that so infuriated Kuleshov, we find an ambitious, multi-layered work which draws upon pre-as well as post-Revolutionary Russian sources and contemporary European influences to reflect the new Soviet life more fully than any other film of the time. Indeed, if we were not predisposed otherwise, Protazanov’s juxtaposition of different registers and realities in Aelita might remind us, if not of Kuleshov’s polemics, then of his own by no means straightforward realist practice, from Mr West to The Great Consoler.5 But the fact that it was made by the ‘wrong’ director at a time when early Soviet production was being valued for quite different qualities, together with its ‘inner space’ project being persistently misconstrued, have all tended to erase the film’s conjunctural specificity.

To grasp this involves sketching a number of contexts in order to explore the crucial significance of the film’s drastic departure from the novel of which it is actually more a critique than an adaptation. What emerges is a work defined by multiple authorship and a product of the emergent ‘cultural industry’ of Soviet film-making—two perspectives rarely brought to bear on the cinema of an era so dominated by the mythology of protean artistic and ideological purpose. A ‘polyphonic’ text also, in Bakhtin’s sense, which allows us to read some of the many discourses that defined the contested pluralism of the New Economic Policy (NEP), Lenin’s contradictory legacy to the infant Soviet state.6

2

‘Anta…Odeli…Uta…’

Premièred at the end of September 1924, Aelita was undoubtedly the major event in Soviet cinema before the international breakthrough of Potemkin in in 1926. Like the German The Cabinet of Dr Caligari [Das Kabinett des Dr Caligari, 1919], which reputedly served as inspiration, it proclaimed a major industrial thrust to produce cinema of ‘international quality’, which could both yield export earnings and compete effectively with imports in the domestic market. To aim at these ambitious goals amid the poverty and contradictory motives of Soviet production in 1923, its producers assembled a remarkable array of talent and scarce resources. They took advantage of the imminent return from exile of a well-known writer, Alexei Tolstoi, to base the film on his latest novel: a fantastic tale of adventure and romance set largely on Mars. Leading actors from the main theatres were engaged to make their film débuts, along with promising newcomers and a vast army of student extras.7 To direct this prestigious subject, one of the most celebrated directors from pre-Revolutionary Russian cinema, Yakov Protazanov, also returned from exile.

Important as these coups must have been, a further vital ingredient was the stylistic novelty which had distinguished Caligari. In place of the German film’s ‘Expressionism’, Aelita deployed the distinctive Russian modernism which was already becoming known abroad under the often inaccurately applied names of its various factions—Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Suprematism and Constructivism—as these were rapidly assimilated into the design-conscious Russian theatre.8 From Tairov’s Kamerny Theatre came the distinguished painter Alexandra Exter as costume designer. Sets were commissioned from her former pupil Isaak Rabinovich, who had recently revolutionised the staid Moscow Art Theatre with his ‘Constructivist’ set for Lysistrata.9 Finally, a German cinematographer was employed to work alongside the Russian cameraman, in recognition of the low level of technical expertise available in a Russian studio at this time.10

As the first Russian film to reflect the contemporary mixture of scientific and popular enthusiasm for astronautics, Aelita had massive potential appeal. After months of carefully nourished rumour about the resources involved in the production, its release was preceded by various publicity stunts, including novel teaser’ advertising campaigns in Pravda and Kinogazeta. In the former, a cryptic message appeared regularly from 19 September 1924: ‘ANTA…ODELI…UTA…’, while the latter explained:

The signals that are being received constantly by radio stations around the world—Anta…Odeli…Uta…—have at last been deciphered! What do they mean? You will find out on 30 September at the Ars Cinema.11

On this occasion, the cinema façade was decorated with giant figures of Aelita and Tuskub, the princess and king of Mars, surrounded by illuminated columns and geometric shapes approximating to the film’s ‘Martian’ décor, and animated by flashing lights. An accompanying orchestra played specially composed music by Valentin Kruchinin.12 Demand for tickets was unprecedented, which kept the touts busy, and huge crowds apparently prevented Protazanov himself from attending the première!

The film, however, turned out to be an ‘adaptation’ which bracketed a drastically reduced version of Tolstoi’s story within an entirely new narrative. This strategy puzzled and disconcerted many critics, but did not prevent the.film becoming immensely popular with cinemagoers.13 The next release to fare anything like as well would be Mezhrabpom-Rus’s 1926 success (involving some of the same team) The Bear’s Wedding, a shrewd exploitation of the vampire motif from a story by Mérimée, which witnesses recall generating a huge fan-mail.14 We shall never know what the large audiences for these films—who were also the readers of Tolstoi’s and other contemporary fantasy novels then abundantly available under the market conditions of NEP publishing—made of them, but we need to bear in mind the likelihood of responses other than the largely negative ones recorded, such as by ‘B.G.’ in Pravda:

The theme of the picture and Tolstoi’s novel, for all its ideological questionableness, has great literary worth. The authors of the scenario, Otsep and Faiko, wishing to correct the ideological side, describe the whole trip to Mars as a dream of the engineer Los. But it is unclear where he goes to sleep, or where and when he wakes up. It is as if he woke up after attempting to kill his wife, but then where do the scenes on Mars come from? And besides, to Tolstoi has been added the story of the engineer’s life before his flight…. The rising of the Martian workers has the stamp of the ‘monumental’ foreign films, striving to convey quantity rather than quality.15

Figure 8. The beginning of Aelita is set specifically in December 1921, amid the chaos bequeathed by the Civil War and the start of the NEP.

Izvestiya ironically proclaimed ‘the mountain has produced a mouse’; while Lunacharsky, writing in Kino-gazeta, hailed it as ‘an extraordinary phenomenon’, but felt that ‘it would have been preferable not to depart from Tolstoi’.16

As actual familiarity with the novel and the film faded, criticism has largely recycled earlier opinions. Thus Thorold Dickinson, writing in 1948, could only speculate: ‘It would be interesting to meet someone who can recall having seen Aelita. Perhaps the film failed to fuse so many divergent styles of acting.’17 One of his sources was no doubt the pioneer English-language historian of Soviet cinema, Bryher, who had also been unable to see Aelita when preparing her Film Problems of Soviet Russia in 1928 but was aware of the eclectic composition of the film: ‘It is reported that actors from opposite schools and pupils from the State School of Cinematography were used in the production, and that very interesting effects were achieved.’18 Controversy raged from the outset, of course, over the stylised Martian décor, with Pravda describing it as ‘like Aida at the Bolshoi’.19 But, for serious Western critics, not opposed to stylisation in principle, the fundamental issue has probably been that first expressed by Rotha in his influential The Film Till Now in 1929.20 Rotha, a passionate admirer of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, insisted that the stylised ‘Cubist’ design of Aelita could not be compared with the earlier German film because it was ‘designed fantastically in order to express an imaginary idea of the planet Mars, and not, as in Caligari, to emphasise the thoughts of a distorted mind’. For later art historians, the issue of Exter’s Constructivist credentials has often loomed larger than any analysis of the film’s plastic achievement.

3

The Mezhrabpom-Rus Initiative

Aelita effectively inaugurated a new production force in Soviet cinema, Mezhrabpom-Rus: a strategic innovation that would do much to rescue filmmaking from the impoverishment it had suffered since nationalisation, but which would also earn the hostility of ‘left’ elements by its apparent compromises with the pre-Revolutionary past and the capitalist West—while also providing support for many of the same ‘left’ directors, including Pudovkin and, later, Kuleshov and Vertov, as well as such foreign leftists as Ivens and Piscator.21 So ingrained has been the doctrine of Soviet cinema’s ‘invention’ ex nihilo during the Civil War ‘agit’ period that the lines of continuity between pre- and post-Revolutionary production have only recently been recognised: yet these are vital to an understanding of the origins of Aelita.

Mezhrabpom-Rus was a quintessential creation of the New Economic Policy. It resulted from an injection of share capital into the existing Rus studio by the Berlin-based organisation Internationale Arbeiterhilfe, known in English as Workers’ International Relief (WIR) and in Russian as Mezhdunarodnaya Rabochaya Pomoshch’, yielding the acronym ‘Mezhrabpom’. Rus itself had been re-formed as an experimental collective on the basis of Trofimov’s pre-Revolutionary production company.22 In the desperate situation that led to nationalisation of the Soviet cinema industry in August 1919, the commissar responsible, Lunacharsky, recognised the need to stimulate production that had some chance of meeting cultural and entertainment criteria, while being in some broad sense politically ‘progressive’. He therefore supported and defended the group who formed the ‘Artistic Collective of Rus’ in early 1918 under the leadership of Moisei Aleinikov, for a long time the force behind Cine-Phono, a trade magazine largely financed by the producer Yermoliev. This collective included Fyodor Otsep, Aleinikov’s former assistant and scriptwriter for such pre-Revolutionary films as Protazanov’s The Queen of Spades [Pikovaya dama, 1916]; Yuri Zhelyabuzhsky, the cameraman and later director; Nikolai Efros, former head of the Moscow Art Theatre literary department, together with one of its assistant directors, Alexander Sanin, and a number of actors from the same theatre. Against all odds, the collective succeeded in producing a Lev Tolstoy adaptation, Polikushka, in 1919–20, which Aleinikov was able to take to Germany and sell in order to raise funds for much-needed materials and equipment.23

But individual enterprise could not solve the problems of a whole industry and, despite formal nationalisation, foreign investment in Soviet production was actively sought in 1922 within the general strategy of NEP.24 The search proved unsuccessful, except for WIR’s subsidiary, Aufbau, offering a 50 per cent investment in a new joint venture, to be known as Mezhrabpom-Rus. WIR may have hoped to infuse the hitherto conservative Rus studio with ‘ideological rigour’, but it was also clearly relying on Rus’s unique—in the Soviet context—capability to produce films which might make their way in domestic and foreign markets. An indication of Aleinikov’s priorities and enterprise is provided by the terms of the script competition announced in September 1923 (with a jury headed by Lunacharsky in his capacity as chairman of the Artistic Council of Russfilm, as the company had now become):

The theme may reflect the past and present of revolutionary and old-world Russia or contemporary life in either a realistic or a romantic treatment. But we do require fullness of content, clarity and entertainment in the plot, drawn in cheerful and wholesome tones, complexity of action unfolding within the framework of the beauties of nature, and a variety of experiences for the heroes.25

The list of suggested themes included in the advertisement offers a valuable insight into the generic possibilities and perceived needs as they appeared to Russfilm on the brink of its expansion:

Aelita, as the new company’s first prestige production, would actually combine no fewer than six of these themes in a novel imbrication, as if seeking to define the studio’s whole field of operations and establish its distinctive approach to both conventional and controversial subjects.

But Aelita was not in fact the first production to emerge from the new enterprise. One week before its release, Four and Five [Chetyre i pyat’, 1924] was reviewed in Pravda as a film ‘coming from Rus, the organ of Mezhrabpom’, in terms which established the pattern of response that would apply to many subsequent Mezhrabpom-Rus releases, while also revealing such rudimentary Party attitudes to cinema as existed at this time. Four and Five was described as showing

the desperate struggle over a terrible death gas invented by aviator and chemist Dimitri with the intention of defending the Republic. The subject is not novel, but technically it is a great success and you watch it with unwavering attention. Ideologically it is not our film…. It is not shown clearly that the invention of the gas was only for the defence of the USSR and not for imperialist needs. For us there are other means of defence. Nothing is shown of our Soviet reality, only the millionaires and a statue of Pushkin…. The film could be shown successfully in a Parisian cinema of today and could have been a pre-war hit…. For a technically well-made film coming from Rus, the organ of Mezhrabpom, such ideological emptiness is both unexpected and unpleasant.26

The same review covered Young Pioneers [Yunye pionery], a short film by Alexei Gan, the editor of Kino-Fot and supporter of Vertov, which is described as ‘a film attempting to have no scenario or director’. Significantly, this is judged mediocre and unsuccessful, but ‘it is our film’.

Here already is the polemical stance against compromised/escapist/ Westernised cinema more familiar from the writings of Vertov, Eisenstein and the LEF group, which amounts to a rejection of ‘NEP culture’ and a repudiation of Lunacharsky’s declared strategy to counter the appeal of foreign cinema—then flooding Soviet screens—by competing in entertainment terms with ‘relaxed’ ideological requirements.27 Mezhrabpom-Rus seems to have been condemned from the outset to incur both Party strictures and ‘left’ wrath, while in fact fulfilling state policy by achieving economic self-sufficiency and creating potential export products, as well as winning back the disenchanted mass audience for domestic production.

More research is required to reveal exactly what influence their German partners may have exerted on Rus. Did WIR perhaps take part in the negotiations for Protazanov, the most successful pre-Revolutionary Russian director still abroad, to come back and create a ‘box-office hit’? Or, more likely, did Aleinikov’s overall strategy to develop the studio coincide with Lunacharsky’s interest in persuading famous artists to return? At any rate, Protazanov, who had directed in both France and Germany from 1920 to 1923, was not invited specifically to make Aelita, but for an historical project, variously reported as Taras Bulba or Ivan the Terrible.28 That neither of these materialised and his Soviet début became Aelita was probably linked with the contemporaneous return of another distinguished émigré, Alexei Tolstoi. WIR may, however, have been involved in the struggle to keep Aelita going as the production costs rose far beyond Mezhrabpom-Rus’s modest resources. But the offer of additional investment by a German company in return for monopoly distribution rights in Europe was apparently declined, presumably in anticipation of the film’s potential to attract rival bids as a ‘Soviet Caligari.29

4

Tolstoi—‘Unlucky in Cinema’

Alexei Tolstoi’s involvement, however token this turned out to be, was clearly part of the original Aelita ‘package’ and a vital ingredient in the cultural politics of the project. a minor aristocrat and distant relative of Lev Tolstoy from the south-east steppe, was already an established author of popular verse, novels and plays before 1917, when he joined the White Army and worked in the propaganda department of Denikin’s staff. Moving to Paris after Denikin’s defeat, he continued to write prolifically for the émigré Russian press and published the first volume of a Bildungsroman sequence, The Road to Calvary, tracing the fate of the Russian intelligentsia across the years of war and revolution.

He also began to modify his public attitude towards the Soviet state, joining the émigré group ‘Changing Landmarks’ [Smenovekhovtsy] and writing:

[since] there is no other government in Russia…except the Bolshevik …we have to do everything to help the last phase of the Russian Revolution take a direction that would make our nation stronger, enrich Russian life, and obtain from the Revolution all its good and just elements.30

Tolstoi contributed a series of similarly conciliatory articles to the Berlin Russian paper Nakanune [On the Eve] in 1922; and in November of that year he joined Mayakovsky and others at a celebration of the fifth anniversary of the Revolution, where he read from his work in progress, Aelita. The full text then appeared in three consecutive issues of the Soviet journal Krasnaya nov’ [Red Virgin Soil], by which time Tolstoi had made his peace with the Soviet regime and returned to live in Moscow. The NEP policy of encouraging ‘repentant émigrés’ to return was bearing fruit, although bitterly contested by such ‘left’ groups as ‘On Guard’ [Na postu] and LEF.

Science fiction had become perhaps the dominant genre of Soviet literature, finding a new popular audience in the market conditions of NEP publishing and serving a wide range of functions, from propaganda to escapist entertainment.31 Tolstoi’s first venture shrewdly combined material he knew well with a scattering of exotic inventions and ill-disguised borrowings. The novel tells of an expedition to Mars undertaken by a resourceful engineer Los, whose wife has recently died, and who is accompanied by a restless ex-soldier Gusev.32 On Mars, or Tuma, they encounter a decaying society, which was first seeded by the invading Magatsitls, as they fled the destruction of Earth’s Atlantis. While Los falls in love with Aelita, daughter of the Martian ruler Tuskub, his companion Gusev captivates her maid. But a rising by the oppressed Martian proletariat, under the leadership of an engineer, interrupts these idylls and leads to civil war in which Gusev takes command. The insurgents are eventually routed by Tuskub’s forces and the Earthmen barely escape. On their return home (via a splashdown on Lake Michigan!) they are fêted as heroes, but Los pines for Aelita and is finally rewarded, yet tormented, by a radio message from Mars in which she calls for him.

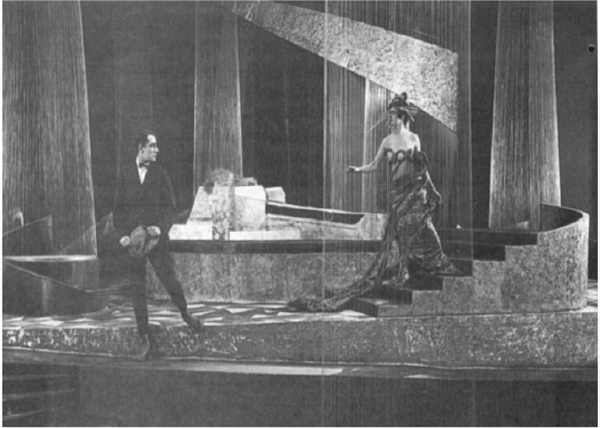

Figure 9. Engineer Los’s day-dream transports him to the court of Princess Aelita (Nikolai Tsereteli and Yuliya Solntseva).

Closer in spirit to Edgar Rice Burrough’s Martian romances (already available in Russian translation) than the didactic Martian utopias of Bogdanov, Tolstoi’s novel had undeniable popular appeal. Yevgeni Zamyatin, author of We [My] and a sciencefiction authority, saw its strengths as well as the obvious weaknesses:

In his latest novel, Aelita, Tolstoi attempted to transfer from the mail train to the airplane of the fantastic, but all he managed to do was jump up and plop back on the ground with awkwardly spread wings…. Tolstoi’s Mars is no further than forty versts from Ryazan; there is even a shepherd there, in the standard red shirt; there is ‘gold in the mouth’ [fillings]…. The only figure in the novel that is alive, in the usual Tolstoian fashion, is the Red Army soldier Gusev. He alone speaks, all the others recite.33

Tolstoi was later to complain that he had been ‘unlucky in cinema’, and in the case of Aelita he had reasonable grounds for complaint.34 For, whatever else it was, Protazanov’s film could scarcely be considered an adaptation of Tolstoi’s novel. Little, in fact, was retained beyond the title and the names of the main characters, while the additions amounted to a substantially new narrative embodying very different themes.

The film begins, in effect, with the novel’s ending and a very different hero. This Los is a sensitive engineer, far from the ‘Elk’ his name evokes in Russian, whose fascination with space travel encourages him to day-dream about life on Mars. He interprets a cryptic message received at a Moscow radio station as coming from the beautiful Aelita, who he thinks has fallen in love with him. This interplanetary fantasy becomes increasingly real to Los when he believes his own wife, Natasha, to be attracted to a suave speculator, Erlich, who is lodged in their apartment. Natasha works at a reception centre for refugees (the film spans the period 1921–3) where, apart from Erlich and his scheming wife (soon to seduce Los’s friend Spiridonov, a fellow space enthusiast), she meets a wounded Red Army soldier Gusev, who eventually marries his nurse Masha and becomes a helper.35

Aelita, meanwhile, is imagined by Los to be in rebellion against her father Tuskub, especially when he curbs her passion for viewing Earth (and Los) through a new apparatus. Natasha, increasingly neglected by Los, reluctantly accompanies Erlich to a decadent ball for anti-Soviet elements, while her husband seeks solace by going to work on a remote construction project. On his return, Los jumps to the conclusion that she has moved in with Erlich and in despair shoots at her. He flees to the railway station, but decides to remain in Moscow and disguise himself as Spiridonov, who has shortly before written to say he is emigrating. He succeeds in building the rocket ship they had long planned and sets off for Mars, accompanied by Gusev, now bored with civilian life, and a stowaway—the amateur detective—Kravtsev, who is investigating Erlich’s swindles and Spiridonov’s seeming disappearance. When they land, Aelita has arranged for her maid to bring the visitors to her and she satisfies her curiosity about Earth customs with a kiss from Los. Gusev charms the maid with his accordion playing, until Tuskub’s militia arrest her for having murdered, on Aelita’s orders, the astronomer who had predicted where the ship would land. Kravtsev is taken to the dungeons where the toiling Martian masses are kept, and are refrigerated when they are not needed. Momentarily, Los imagines that his wife is still alive and begs her forgiveness.

Meanwhile Gusev successfully appeals to the Martian workers to ‘throw off their thousand-year hypnosis by the Elders’ and Aelita offers to lead the uprising. But when the insurgents have overcome the Elders, she persuades them to lay down their arms, then orders the militia to open fire. Los pushes her off the dais—and finds that it is his wife he is pushing—before awakening from his dream in the station where he had gone after the shooting. The original ‘Martian’ message is revealed as part of an advertisement slogan for tyres! Gusev and his wife, waiting for a train to the east, follow as he returns to his apartment and discovers Natasha unharmed. Upstairs the militia are arresting Erlich on suspicion of Spiridonov’s murder, while Los retrieves the rocket plans that Spiridonov had hidden and destroys them, telling Natasha that ‘a different sort of work awaits us’.

The deeper cultural and ideological significance of both the novel and the film’s new scenario will be considered further below, but at this point it is worth noting that Tolstoi’s Martian tale can scarcely be regarded as innocent escapism. Its ‘ideological questionableness’, as we have seen, was noted as a matter of course in the Pravda review; and Zamyatin’s contemporary article drew attention to Tolstoi’s reliance on the Theosophist mystic Rudolph Steiner for his Atlantis myth. Even at a superficial level, the novel’s rejection of Mars—whether construed either as the decadent West or the Imperial Russian past—seemed ambivalent.

Aelita was of course written while Tolstoi was still abroad. It may well be significant that one of his first works after returning to the Soviet Union, Azure Cities, has a remarkably similar theme to that of the Aellta film.36 In it an idealistic young communist architect dreams of building ‘azure cities’, but when illness forces him to return to his provincial home town, he finds that little has changed since the Revolution, except for the worse, as opportunists take advantage of NEP. In despair, he sets fire to the town, hanging his utopian designs aloft on a pole, then turns himself over to the authorities with the bitter words: ‘Life does not forgive rapt dreamers and visionaries who turn away from it.’ Although Tolstoi would also pioneer the fully fledged Soviet science-fiction thriller in The Garin Death Ray, Protazanov’s Aelita ‘adaptation’ anticipated the direction of the novelist’s more serious and personal work, culminating in the third volume of The Road to Calvary.

5

Protazanov—On the Threshold of a Dream

The impetus to tamper seriously with Mezhrabpom-Rus’s prestigious literary property, whatever the probable outcry, seems to have come from Protazanov, who was certainly no stranger to controversy. Indeed his early career had benefited greatly from the scandal created by the film he co-directed giving a lurid account of the circumstances that led to Lev Tolstoy’s death, The Great Man Passes On [Ukhod velikogo startsa, 1912].37 Later, within weeks of the October Revolution, his Satan Triumphant [Satana likuyushchii, 1917] became a byword for ‘diabolism’, with its Expressionistic portrayal of the havoc wrought on a pastor and his flock by the devil incarnate.38 But, on the strength of his surviving pre-Revolutionary work, it would be a mistake to categorise Protazanov as a mere sensationalist or opportunist. He was already a complex and above all a versatile artist, placing his skills and stylistic daring at the service of the dramatic material chosen for each film—which choice would seemingly often be influenced by topicality and the potential for publicity.

One of his scenarists on Aelita, the young playwright Alexei Faiko, recalled:

Protazanov was very keen to do something contemporary. Work on the script was neither fast nor smooth. Protazanov made all sorts of demands… [he] was always searching and striving for something new and more interesting.39

That Protazanov should want to deal with the Soviet reality to which he had returned seems highly plausible, if only to ward off the inevitable suspicion attaching to returned émigrés and likely attacks from the vigorous young opponents of entertainment cinema who had increased their influence during his absence. The cost of a full-scale Martian spectacle was another practical reason for revision and, despite contemporary rumours of reckless extravagance (possibly encouraged by Aleinikov as a shrewd publicist), the original set designs for Aelita still proved too costly and had to be reduced in scale.40

The key to combining the exotic potential of Tolstoi’s Martian romance with ‘something contemporary’ proved to be a device which Protazanov had used to great effect in his first production abroad, The Agonising Adventure [L’Angoissante aventure, France, 1920]. This was the ‘uncued dream’, whereby an apparently realist narrative moves into dream mode unbeknownst to the spectator until the unexpected dénouement of awakening—of which the best-known later example is probably Lang’s Woman in the Window [USA, 1944]. But, whereas this device functions in The Agonising Adventure to enclose a typical tragic melodrama of the pre-Revolutionary Russian cinema within an acceptably sophisticated French ‘frame’, Aelita attempts an altogether more complex structure. Here dream and reality alternate from the outset, with a minor motivation in Tolstoi’s novel—Los has thrown himself into invention after his young wife’s tragic death—transposed into Los’s neurotic jealousy of his living wife Natasha, which produces the ‘Martian narrative’ as a compensatory fantasy satisfying (or combining?) his erotic frustration and engineering ambition. This narrative hierarchy is then destabilised when Los appears to build the rocket which will take him to his imaginary Mars, until the resulting paradox is resolved by his awakening in the railway station. So effective was this device that Protazanov would use it again, for the British soldier’s dream, in his first sound film Tommy [Tommi, 1931].41

Protazanov’s Los thus becomes a recognisably Russian hero and, as such, one virtually unique in early Soviet cinema: a ‘bourgeois specialist’ ostensibly committed to building communism, but still emotionally, perhaps unconsciously, unadjusted to the new order—a Soviet version of Russian literature’s traditional ‘superfluous man’. Protazanov had succeeded in getting from his scenarists a remarkably apt vehicle for entering the world of Soviet Russia, a time machine that deals with the contradictory present of the NEP in terms of a discredited past (flashbacks to the pre-Revolutionary privileges of Erlich’s cronies) and an imagined future, still shaped by Symbolist culture. Aelita recapitulates the ‘threshold’ strategy of The Agonising Adventure by interleaving a Russian film d’art (moreover one more ambitious than anything attempted before the Revolution) with the portrayal of Soviet reality, as seen with the affectionate curiosity of the returning native.42

Paris—Moscow—Mars

Although the Martian scenes occupy little more than a quarter of the film, they have constituted the film’s main claim to fame. But the question posed by Rotha and others still stands: is their fantastic décor ‘motivated’? Certainly Rotha’s unfavourable comparison with Callgari can be rebutted: the stylisation of Aelita represents just as much ‘the thoughts of a distorted mind’ as does that of the German film. Indeed the relationship between the two films seems to have been quite explicit, at least for those involved. According to Huntly Carter, an early traveller to Soviet Russia and writer on its theatre and cinema, Alexandra Exter personally cited Caligari as her main inspiration.43 This would be consistent with the assumption that Caligari pointed towards an explicitly cultural strategy for European national cinemas, faced with growing American trade hegemony and protectionism. Only by creating ‘cultural difference’ could they hope to compete with the efficiency and universal appeal of American entertainment cinema. So, in place of the ‘Expressionism’ of Caligari, Aelita deployed the latest fruits of the close relationship that linked avant-garde Russian artists with the theatre. But this ‘motivation’ scarcely does justice to the remarkable integration of architecture, décor, costume and indeed acting, which remained unequalled until Lang’s Metropolis [Germany, 1926]—a film backed by much vaster resources and reputedly in part inspired by Aelita.44

Here again, the impetus may well have come from Protazanov, who had spent his French sojourn amid the Russian émigrés of the Ermolieff [Yermoliev] group who were close to the avant-garde cinéastes then pre-occupied with introducing modernist art and design into their productions.45 In Paris Protazanov would certainly have been aware of the activities of Louis Delluc, prophet of photogénie and organiser of the first French screenings of Caligari in 1921, and of Ricciotto Canudo, promoter of Le Club des Amis du Septième Art (CASA), which brought together artists, architects, poets and musicians to contribute to raising the artistic level of cinema.46 He might even have known of L’Herbier’s production L’Inhumaine, started in September 1923, which combined the Art Deco architecture of Robert Mallet-Stevens with a kaleidoscope of striking décors, costumes and artefacts, including a laboratory set designed and built by the Cubist painter Fernand Léger.47

Léger was also one of the circle of French artists whom Alexandra Exter already knew from pre-war visits to Paris and, when she moved there permanently in the same year as Aelita, she soon began teaching at his Académie de l’Art Moderne.48 We may never know the exact sequence of events that led to Exter’s involvement in Aelita, but it is clear that, whether this was cause or effect, it brought to the production both a cosmopolitan awareness of design trends in Western Europe and a distinctive Russian tradition, namely that of the Moscow Kamerny Theatre. For it was at the Kamerny that Exter had played a leading part in realising Alexander Tairov’s vision of an ‘emancipated’ theatre in the three landmark productions she designed: Annensky’s Thamyras Cythared [Famira kifared] in 1916, Wilde’s Salomé in 1917 and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in 1921.49

Tairov had been inspired in large part by Edward Gordon Craig’s 1911 Moscow production of Hamlet, with its novel combination of two-and three-dimensional décor aiming at a Symbolist synthesis.50 The Wagnerian Adolphe Appia had challenged the dominant naturalistic theatre with a proposed integration of set, actors and plot within a mood created largely by music; and Georg Fuchs’s Theatre of the Future encouraged not only Tairov but also Meyerhold to treat the stage as an entirely artificial self-sufficient ‘world’, with increased emphasis on nonverbal, plastic and phatic means of communication.51 Tairov’s first steps towards the realisation of this new ideal in 1914–15 involved collaboration with the painters Pavel Kuznetsov and Nataliya Goncharova, members, like Exter, of the explosive Russian avant-garde movement that began to distance itself from Symbolism with the ‘Blue Rose’ and ‘Wreath’ exhibitions of 1907. A contemporary critic prophetically dubbed them ‘heralds of the new Primitivism to which our modern painting has come’; and indeed Primitivism was to be the Leitmotif of this factional movement until, from about 1913, Futurism introduced a utopian social and quasi-scientific rationale for its highly eclectic activity.52

Exter, almost alone among these artists, spent considerable time in Italy and France between 1908 and 1914, mixing in Futurist and Cubist circles, while exhibiting in all the main Russian avant-garde shows. By the time the outbreak of war confined her to Russia, her painting reflected these diverse influences in a highly chromatic abstract Cubo-Futurism. The war period brought the new outlet of theatre and, back in her native Kiev, led her to establish what was probably the first art school to teach the formal grammar of modern art and deliberately lead its students towards abstract work.53 Significantly, many of the young Ukrainian artists who studied with her in Kiev and Odessa from 1916 to 1919 went on to become leading stage designers, including Bogomazov, Meller, Petritsky, Tchelitchew and her collaborator on Aelita, Rabinovich.54 While their idioms would vary greatly, Exter had reached a degree of mastery at the very point where the Futurist quest was about to face its final challenge. The Kamerny Salomé opened less than a month before the October Revolution and its importance is attested by Andrei Nakov:

This production provided a stylistic example which would nourish ‘Constructivist’ production until almost the end of the 1920s. In Salomé, skilful lighting made the geometric forms vibrate, giving an impression of floating, while moving on the vertical. The actors’ costumes were the result of an ordering of geometric forms and their acting was constrained by the limits of these forms. Like the scenery for Victory Over the Sun in 1913 (the real prototype of this formal sequence), the décor for Salomé produced a strange monumentalisation of dramatic tonality. The new pathos of the ‘machine age’ was born.55

Exter’s theatre design from the start had aimed to give three-dimensional depth to the stage picture and to animate its immobile décor. Not only did Aelita continue this line of design experiment, but it made use of Kamerny actors, including Nikolai Tsereteli—the Kamerny’s Romeo—making his screen début as Los/Spiridonov. But, whereas Romeo and Juliet was embellished with extraordinary ‘frozen dynamics’, echoing Boccioni’s sculpture, Aelita received a more austere treatment and moreover one precisely conceived for the medium of cinema.56

As in cinema history, canonic considerations in art history seem to have told against Exter. It would certainly be wrong to classify her and Rabinovich’s work as Constructivist’ in the narrow sense defended by Christina Lodder, but equally the latter’s critique seems to be based on doubtful premisses:

aesthetic factors dominate [Exter’s] creations for the School of Fashion… and her costume designs for the film Aelita. In both these branches of work considerations of strict utility played no role, and Exter’s use of geometrical forms as decorative elements stressed the essentially painterly nature of her approach to clothes. Aelita’s costume billowed out into extravagant vegetable protrusions more reminiscent of Art Nouveau than Constructivism, and her maid’s trousers, constructed of rectangular metallic strips, seemed designed to impede rather than facilitate movement. It is significant that whereas Stepanova and Popova used the theatre to realise prozodezhda [‘production’ or work clothing] Exter produced these decorative fripperies.57

Another historian of Russian and Soviet art, John Bowlt, makes the important observation that, while the Aelita costumes may look ‘unwieldy and rather absurd on paper, ‘in the movie they function perfectly’. This is because they rely upon and actually exploit the changing viewpoint of cinema and its artificial ‘additive’ space.58

Knowing that in the black and white film, color in her designs would be superfluous, Exter restored to other systems of formal definition. This, together with her acute concern with space as a creative agent, prompted Exter to use a variety of unusual materials in the construction of the costumes and to rely on sharp contrasts between material textures—aluminium, perspex, metal-foil, glass.59

Many judgements on Aelita have been passed without doubt on the basis of drawings or stills alone, but viewing confirms how accurately the effects were calculated for this (literally) fantastic, yet flat and monochrome, world of Los’s dream—a very different challenge from the theatre projects tackled by other artists during the short-lived moment of Constructivism, but one approached according to the same analytic principles:

both in Exter’s costumes and Rabinovich’s sets, industrial materials served a definite objective: they defined form in the absence of color; in their transparency or reflectivity they joined with the space around them and created an eccentric montage of forms.60

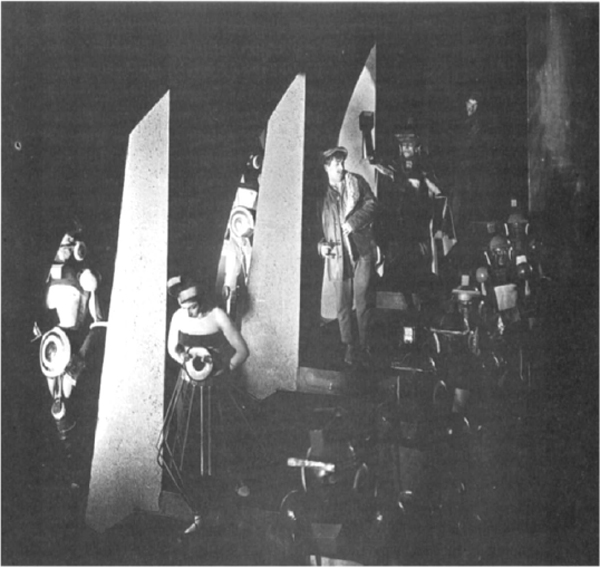

Figure 10. Los’s dream companions, Kravtsev (Ilyinsky) and Gusev (Batalov), meet the Martian slave-labourers underground, when they are arrested with Aelita’s maid, Ikushka (left).

The Martian dream in this Aelita was not after all intended as a vision of the future or an exercise in anti-aesthetic design efficiency. On the contrary, thematically it had to combine an impression of extreme technological refinement with the trappings of a feudal, hieratic society and an erotic motive. Hence the highly effective play of stasis and movement centring on the representation of light—petrified rays, dynamic translucent forms echoing the perspex sculptures of Gabo—and the subtle evocation of an Atlantean-Egyptian autocracy largely through costume and make-up. By evoking a modified Kamerny style, Protazanov was acknowledging the power of the Symbolist tradition, yet also gaining distance from it through the film’s cultural montage form.

In practice, it appears that both Rabinovich’s ‘Constructivist’ cityscape and Simov’s sets proved too expensive for Mezhrabpom-Rus and much of the actual design seen in the film was by Viktor Kozlovsky, an accomplished cinema art director from the pre-Revolutionary industry who had gained valuable experience on its lavish historical subjects and, especially, on the fantastic live-action films of Wladyslaw Starewicz.61 Kozlovsky seems to have occupied the same supervisory role at Mezhrabpom-Rus as the art-department heads of Hollywood studios, mediating between bold stylistic innovation and the demands of budget and timetable. And all that is not ‘Martian’ in Aelita was presumably designed by him.

For it is not Mars, but Moscow, that is the film’s main setting. As befitted a film directed by a returning exile, it uncovers an extraordinary range of the early Soviet experience—from the crowded trains and stations as recovery begins after the Civil War, through relics of the ancien régime (climaxing in the decadent night-club which resembles nothing so much as a bal des victimes), to signs of the new culture—posters, an agit-performance at the evacuation centre, the orphanage where Masha goes to work—and industry (the radio station and bustling construction sites where Los works) and the streets and crowded apartments of Moscow at the peak of the New Economic Policy. More thoroughly than in any other Soviet film of the period, the precarious equilibrium of the NEP, with idealism and opportunism both rife, is exposed and indeed becomes the film’s dramatic and ideological pivot.

7

Dreamers and Detectives

What undoubtedly must have seemed most attractive about filming Aelita was the prospect of Soviet cinema’s first science-fiction film, for the early 1920s had seen an extraordinary explosion of Soviet writing and publishing in a genre which had previously been the preserve of the intelligentsia. The Revolution had given fresh impetus to a long-standing Russian fascination with programmatic fantasy, itself already enshrined in the Bolshevik tradition. Lenin had titled his 1902 strategic pamphlet What Is To Be Done? explicitly after Chernyshevsky’s ‘underground’ novel written in 1862, which included the dream of a future social order based on female emancipation and the rational division of labour. Another Bolshevik leader, Alexander Bogdanov, had responded to the defeat of the 1905 Revolution with a novel, Red Star [Krasnaya zvezda, 1908], in which a discouraged Russian activist is inspired by the discovery of a Communist utopia on Mars.62 Now the creation of utopia was a state aim; and even H.G.Wells, one of the many foreign science-fiction writers already well known in translation, was surprised by Lenin’s enthusiasm for technological and even interplanetary speculation amid the country’s devastation in 1919.

Surveying the prodigious range of science-fiction publishing during NEP, from the experimental (a ‘cinematic montage’ novel by Bobrov and a ‘factographic’ collaboration by Shklovsky and Ivanov) to the ephemeral, Leonid Heller concludes simply that ‘science-fiction accompanied Soviet literature from the moment of its birth’.63 Indeed fantastic adventure and the characteristic Soviet genre of detection-cum-disaster novel, the ‘Red Pinkertons’, created a short-lived common culture, at least among urban workers and intellectuals. A good example was Marietta Shaginyan’s Miss Mend [Mess-Mend, 1924], featuring an intrepid female detective and Fantômas-like situations, published under the pseudo-American nom de plume ‘Jim Dollar’ with cover designs by the Constructivist Rodchenko, and filmed for Mezhrabpom-Rus as a serial by a group consisting largely of Kuleshov alumni, though with Protazanov’s ‘discovery’, Ilyinsky, playing the lead.64 For, in the character of the comic detective Kravtsev, realised with manic precision by one of Meyerhold’s young actors, Protazanov had unerringly caught the cultural pulse of the period—Eccentric, populist and fascinated by all things American.65 He also succeeded in defusing the essentially reactionary thrust of Tolstoi’s Smenovekh nationalism and anti-Semitism, by making the film in effect a critique of ‘cosmism’. It was the strident utopianism of the ‘proletarian’ writers promoted by Bogdanov’s Proletkult organisation that gave rise to this tendency,66 mocked by Trotsky:

The idea here approximately is that one should feel the entire world as a unity and oneself as an active part of that unity, with the prospect of commanding in the future not only the earth, but the entire cosmos. All this, of course, is very splendid and terribly big. We came from Kursk and from Kaluga, we have conquered all Russia recently, and now we are going on towards world revolution. But are we to stop at the boundaries of ‘planetism’?67

Beneath its derivative surface, Tolstoi’s novel also remained faithful to a mystical tradition in Russian fantasy and science fiction. Probably the most pervasive source of this was the late nineteenth-century religious thinker Nikolai Fyodorov, who preached in his ‘Philosophy of the Common Task’ a mystical, yet literal millenarianism. The achievements of science, including travel to other planets, victory over death and the realisation of a heavenly utopia on earth were all linked goals in Fyodorov’s influential doctrine and their imprint can be found across a remarkable range of Russian thought and art. Even Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the rocket pioneer, was one of many inspired by Fyodorov and, significantly, he did not win final support for his scientific research until he too published a programmatic novel, Beyond the Stars, in 1920.68 But there was also widespread interest in theosophy, in Spengler’s doctrine of the decline of the West and in the anti-Semitism of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, traces of which can all be found within the nostalgic romanticism of Tolstoi’s Aelita.69 To this extent unreconstructed nationalists found common cause with the ‘proletarian’ poets in a shared conviction of Soviet Russia’s destiny to conquer death, the world and the universe. Without some understanding of this context, the particular irony of Protazanov’s revision is lost.

Creating the New Man

Where might the ideological strategy for revising Tolstoi into a more topical tract for the times have originated? One possible answer is to be found in the career of the co-scenarist Alexei Faiko, a newcomer to cinema paired with the young though already experienced Fyodor Otsep. If Otsep brought his pre-Revolutionary experience of ‘psychological’ scripting to the project—including the notable Queen of Spades he had written for Protazanov in 1916—we may suppose that Faiko contributed a sharper sense of contemporary ideology. Essentially a playwright, he had already scored a precocious success in 1923 with Lake Lyul, a detective story set in an imagined capitalist country, directed at Meyerhold’s Theatre of the Revolution by the future film director Abram Room. Faiko’s later successes of the 1920s would all satirise the careerism that flourished openly under NEP; and his most famous play, The Man With the Briefcase, dealt directly with the issue of the pre-Revolutionary intelligentsia’s adjustment—or lack of it—to Soviet demands. Recasting Tolstoi’s somewhat cardboard hero as a dreamer obsessed with an erotic Martian fantasy situates him in the Symbolist tradition, and perhaps links him with Wells’s apocalyptic fantasy ‘A Dream of Armageddon’ (also a ‘dream counterpoint’ narrative); above all it makes him a more complex and, as suggested earlier, recognisable character in the Russian vein.

He has indeed a precursor in Dostoyevsky’s late story ‘The Dream of a Ridiculous Man’.70 In this the narrator is overcome by a feeling of uselessness and contingency in relation to the contemporary world and decides upon suicide, only to fall asleep and dream of his resurrection before being transported to a planet similar to Earth where the whole cycle of the Golden Age myth is in progress. The ridiculous man’ believes he has corrupted this paradise and caused its Fall: he begs the now warring inhabitants to kill him, by crucifixion, but they refuse. He then wakes, convinced of the need to preach the ‘old truth’—‘love your neighbour as yourself’. Here, before the vogue for Wellsian ‘scientific romance’ which would prove so influential upon later Russian utopian materialists, we find a curious fusion of Dostoyevsky’s radical evangelism and his anticipation of the dystopic vein that would dominate Russian Symbolism. It has been suggested that the story marks a further refutation of What Is To Be Done? and in particular its vision of a future Crystal Palace, expounded in the ‘fourth dream’ of one of the characters, Vera Pavlovna.71 Dostoyevsky had already attacked Chernyshevsky’s novel in his Notes from the Underground; now he adopted its dream form to imagine a ‘moral utopia’ which could result from an apocalyptic conversion experience due to what Bakhtin identifies as a ‘crisis dream’.72

The thrust of Otsep’s and Faiko’s scenario for Protazanov is towards a Soviet model of this conversion allegory. Although Los is shown first as a conscientious Soviet citizen married to an equally conscientious wife, both of them willing to put duty before domesticity, the arrival of Erlich triggers their latent dissatisfaction. Hitherto Los has been able to keep his rocket researches with Spiridonov and his Martian dream as a ‘private’ domain, a compensation for the dissatisfactions of everyday life and work. But, when Erlich is assigned to the apartment spare room he has used for research, the state implicitly invades such remaining pockets of bourgeois individualism’: Los longingly traces Aelita’s name on the dusty ornate window of his threatened sanctuary and summons her image immediately before the chairwoman of the Housing Committee announces the unwanted lodger. Los’s unconscious response is to fantasise Erlich’s seduction of his wife, as ‘justification’ for his sense of loss, while this erotic fantasy is acted out in the calculated seduction of Los’s alter ego Spiridonov by Erlich’s wife Elena. Indeed, as Leonid Pliushch notes in his acute reading of the film against the background of Tolstoi’s reactionary Smenovekh sympathies, the film’s ‘doubling’ of the novel’s single character into a ‘good’ and a ‘bad’ engineer effectively echoes Tolstoi’s identification of Mars with the decadent West and also with the ‘paradise lost’ of tsarist Russia.73 Spiridonov actually emigrates under the influence of Elena—his note confesses ‘the past turned out to be stronger’—and Los, symbolically, starts his dream flight to Mars still disguised as Spiridonov (the same actor plays both roles).

The interpretation of Los twice killing the image of his wife proposed by Pliushch identifies the first jealousy ‘murder’ with the petty-bourgeois world of NEP and the second, of Aelita, as a political act necessitated by her betrayal of the Revolution. This reading gains support from the crucial linking of Natasha and Aelita through ‘transgressive’ intercutting, first when Los embraces Aelita after arriving, then when he pushes her off the podium above the main Martian arena as she orders the capture of the disarmed workers. Indeed an early image of the exotic Aelita is ironically intercut with Natasha scrubbing at the sink. Killing the fantasy of Aelita, as well as his distorted image of Natasha (whose name, Pliushch notes, signifies ‘she who is born’), is the necessary prelude to her ‘rebirth’ as a true Soviet woman and to Los’s regeneration as a ‘good’ Soviet engineer. In terms of allegory, there is a distinct echo of Mayakovsky’s Mystery Bouffe, which ends with representatives of the ‘unclean’ class killing Queen Chaos and declaring ‘the door into the future is open’.

9

Back through the Looking-Glass

Aelita clearly disconcerted its first critics through a failure to respect genre and narrative conventions; and the Soviet critical tradition has eventually categorised it as a kind of generic melting-pot, from which can be traced Protazanov’s subsequent comedies with Ilyinsky and, in Batalov’s Gusev, the early evolution of the obligatory ‘positive hero’.74 Such a view, however, though convenient, denies the film’s integral structure and contemporaneity. One way to retain these, as suggested at the outset, is to adopt the methodology applied by Bakhtin in his 1929 study of Dostoyevsky and consider Aelita as a ‘polyphonic’ work. Thus we are free to consider how and why its different discourses coexist, and what kinds of dialogue they conducted with its original audience.

Bakhtin’s book on Dostoyevsky also contains a highly relevant analysis of ‘The Dream of a Ridiculous Man’, treating this as a prime instance of the genre of Menippean satire’, which may help to define more precisely the processes at work in Aelita. According to Bakhtin:

The most important characteristic of the Menippea lies in the fact that the most daring and unfettered fantasies and adventures are internally motivated, justified and illuminated here by a purely ideological and philosophical end—to create extraordinary situations in which to provoke and test a philosophical idea…. A very important characteristic…is the organic combination within it of free fantasy, symbolism, and—on occasion—the mystical-religious element, with extreme…underworld naturalism…. The Menippea is a genre of ‘ultimate questions’. [It] seeks to present a person’s ultimate, decisive words and actions, each of which contains the whole person and his whole life…. [It] often includes elements of social utopia which are introduced in the form of dreams or journeys to unknown lands…. Finally, the Menippea’s last characteristic—its topicality and publicistic quality. This was the ‘journalistic’ genre of antiquity, pointedly reacting to the issues of the day.75

In a fairly obvious sense, Protazanov’s film amounts to a ‘menippea’ based on the would-be epic of Tolstoi’s novel; and the process which achieves this is what Bakhtin termed ‘carnivalisation’.76 The crucial aspect of carnival, he argues, is the ambivalent ritual of crowning and discrowning, which embodies notions of change, relativity, parody, death, renewal, etc. Typically, the slave or jester is crowned and thus, temporarily, the world is turned upside down.

It is Bakhtin’s powerful concept of carnival that may help illuminate the organic function of otherwise puzzling aspects of the film. Consider, for instance, the role of Kravtsev, the fool, jester, doggedly pursuing his investigation and eventually helping unmask Erlich; or the extraordinary pantomime of Gusev being forced to rush through the Moscow streets in women’s clothing when his wife hides his own clothes to prevent him going to Mars. What could be more ‘carnivalesque’, more subversive of Tolstoi’s romanticism, than the start of the space flight, with Gusev cross-dressed, Los disguised and Kravtsev playing ‘Pinkerton’? Bakhtin, both in his acute analysis of the Dostoyevsky story and his ‘historical poetics’, offers more insight into this much-maligned film than cinema history has yet produced.

In the historiographic tradition of belittling Aelita it has become customary to invoke the animated film Interplanetary Revolution [Mezhplanetnaya revolutsiya] released in the same year as a ‘parody’ of it.77 In fact, viewing confirms that there is no discernable relationship between the two (although a script for an unrealised parody of Aelita by Nikolai Foregger apparently exists in the cinema archives) but the idea clearly remains attractive, since Protazanov’s film represents an anomalous mingling of genres and ideologies.78

Much has been made of the fact that its subject and genre(s) were not repeated, as if to confirm an implicit verdict of misjudgement or failure: even the sympathetic Leyda describes it as Protazanov’s ‘least important’ Soviet production.79 This, however, is to apply too narrow and conventional criteria. For Aelita can surely lay claim to being the key film of the early NEP period, born of a unique moment in post-Revolutionary Soviet society, reflecting its realities as well as its aspirations in a complex and original form, and linking its hitherto isolated cinema with important currents in world cinema. Rather than serve as a model for future films, it chronicled the acute period of adjustment that followed the end of the Civil War—the film’s time-span of 1921–3 is crucial—and probed the new contradictions of NEP.80 Aelita may have earned the anathemas of Vertov and LEF, standard-bearers of the new ‘factography’, but it was by no means out of step with other, less dogmatic, currents of artistic innovation, like the young writers of the Serapion Brotherhood, or of such individualists as Zamyatin and Olesha.81 With its bold juxtaposition of diegetic levels and complex reworking of both literary and visual sources, the film celebrates a heterogeneity and topicality that are, in their way, as impressive as the achievement of either Kuleshov or Eisenstein at this early stage in Soviet film-making. More than their first polemical, propagandistic sketches for a radically new cinema, Aelita appears truly, in Bakhtin’s sense, a ‘polyphonic’ work, conducting a dialogue between past and present which is traversed by as many different discourses as indeed were their later works.

But did Aelita in fact have any successors? The film that comes closest to its carnivalesque spirit is probably Mezhrabpom-Rus’s 1925 short Chess Fever [Shakmatnaya goryachka], which again combines fantasy, slapstick and street realism in a highly topical satire, with another eclectic cast—this time consisting largely of film-makers, including Protazanov himself.82

Beyond this immediate echo, Aelita looks forward to the elaborate ‘making strange’ of Soviet life attempted in Ermler’s masterly A Fragment of Empire [Oblomok imperii, 1929] by means of an amnesic protagonist. The only other Soviet film before the 1960s which makes similar use of a fantastic dream counterpoint may well be Room’s suppressed A Severe Young Man [Strogii yunosha, 1934].83 But during the 1940s this form would flourish abroad in fables both Freudian (Lady in the Dark, Spellbound, Dead of Night) and philosophical (A Matter of Life and Death, Orphée).84 Aelita, like its director, richly deserves rescuing from the periphery of a largely static, parochial view of early Soviet cinema.85 To do so involves breaching the cordon sanitaire that has long protected the canon of Soviet ‘left’ modernism from its antecedents and competitors, and taking new bearings amid the cultural, economic and political cross-currents of the 1920s.