The Return of the Native: Yakov Protazanov and Soviet Cinema

Among the many film-makers who left Russia during the Civil War was Yakov Protazanov (1881–1945), one of the flourishing pre-Revolutionary film industry’s most prominent directors. The more than eighty movies he had made since his directorial début in 1911 included the top-grossing film of Russian cinema, The Keys to Happiness [1913], and the most infamous product of its dying days, Satan Triumphant [1917]. From 1920 to 1923, Protazanov lived in Paris and Berlin, making a name for himself in both French and German cinemas.1 In Berlin, in 1923, he received a visit from Moisei Aleinikov, one of the directors of the Rus studio (soon to become Mezhrabpom-Rus), who persuaded Protazanov that the time was right for him to return home.2 Three weeks later he was back in Moscow, and shortly thereafter at work on his first Soviet film, Aelita. A recent Soviet reference book on film says that Protazanov was among the originators of the ‘acting school’ in Soviet cinema3 but, to aspiring young directors, the return of the king of Russian silent cinema meant something quite different indeed.

Protazanov quickly re-established himself as a major, if not the preeminent, director of the Soviet screen. It is probably safe to assert that no other director in the first decade of Soviet cinema had as varied—and unpredictable—an oeuvre. Certainly no other Soviet director was as prolific and as consistently successful at the box office. The consummate professional, Protazanov was immune to the political and artistic controversies bedevilling his younger, more ‘Soviet’ colleagues, both due to his temperament and his record of commercial success.4 He made ten silent films for the Mezhrabpom-Rus studio in six years, beginning with Aelita in 1924 and ending with The Feast of St Jorgen [Prazdnik svyatogo Iorgena] in 1930.

By way of comparison, the output of those young directors whose names are virtually synonymous with Soviet silent cinema (in the West, anyway) was dramatically lower. Sergei Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Dziga Vertov, Alexander Dovzhenko and the team of Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg each made only four full-length features in the same period. These men made ‘difficult’ films not intended as light entertainment for mass audiences, but the figures are also comparable for those major directors from the younger generation who did make movies more easily accessible to general audiences. Boris Barnet made six films, Fridrikh [Friedrich] Ermler four, and Sergei Yutkevich, two.

In the context of the stormy cultural politics of the early Soviet film industry, these figures were significant, and not necessarily attributable to the younger directors’ inexperience. The first point to be made is somewhat obvious, but none the less important: the more films he has on the market, the more potential influence a director has with audiences and studios. This was definitely the case with Protazanov, whose pictures were crowd-pleasers almost guaranteed to draw at the box office. The second point is that to the young cohort, Protazanov symbolised everything they perceived to be wrong with the Soviet film industry in the 1920s–its emphasis on profits, its lack of support for experimentation, its ‘pandering’ to the tastes of the masses. Why was ‘Soviet power’ banking on ‘the little Moscow merchant’ to create the new cinema?5

The social history of Soviet cinema and the history of early Soviet culture cannot be fully understood without reference to the most popular, really the only truly popular, native director of the 1920s—Yakov Protazanov. Most of the revolutionary’ masterworks which made Eisenstein and Pudovkin and others ‘household’ names in avant-garde artistic circles in the 1920s were seen by few Soviet filmgoers—and liked by fewer still. As we shall see, Protazanov’s Soviet films were widely distributed, enjoyed runs of several weeks in the largest theatres, and consistently earned profits for the studio. These by themselves serve as adequate indicators of popularity but, to cite additional evidence, Protazanov’s movies were frequently named in the ‘top ten’ surveys conducted among audiences. Throughout his career he seemed to have an uncanny understanding of what viewers liked, whether those viewers were Russian, French, or Soviet.

Because Protazanov came to Soviet cinema as a mature artist, his career is a particularly interesting and significant one which has the potential to illuminate key issues in the development of Soviet society. By virtue of his family background, education, and professional experience, Protazanov was the quintessential bourgeois specialist’—so his story can shed light on the role of the ‘former’ middle classes in the formation of the new society. And because he lived and worked abroad both before and after the Revolution—and made films that were recognisably ‘Western’ in style—Protazanov and his movies can elucidate the extent to which nascent Soviet culture relied on Westernised pre-Revolutionary traditions. That this director, labelled in his time a ‘reactionary’, ‘socially primitive’ maker of ‘shallow entertainment’ pictures, not only survived but prospered as a Soviet film-maker is a testament to the tenacity of the old tradition and the adaptability of its leading practitioner. Protazanov, who served as a bridge between the Russian past and the Soviet present, is an outstanding example of the importance of ‘transitional’ figures in the evolution of Soviet popular culture.

When Protazanov made the crucial decision to return to Soviet Russia in 1923, the battle lines on the cultural front were only starting to be drawn. Because the director was a circumspect individual, writing virtually nothing and responding to interviews as laconically as possible,6 we can only conjecture about his true reasons for coming back and his reactions once home. Even his Soviet biographers make no effort to claim a political awakening for him. Given the circumstances of his early life, however, it is reasonable to surmise that Protazanov might have been a little bemused to find himself at the centre of a controversy in which he was cast at the age of 42 as a representative of the ‘old order’.7

Yakov Alexandrovich Protazanov was born in Moscow in 1881, on his mother’s side the member of a well-to-do merchant family named Vinokurov.8 His father, a somewhat shadowy figure of whom Protazanov’s conservative grandfather disapproved, was from Kiev, and probably an accountant by profession. The Vinokurovs were not the prototypical, traditional merchant family, although they did have some patriarchal and authoritarian characteristics. Contrary to the stereotype, Protazanov’s mother was reasonably well educated, preferred to speak French at home, and took her children to the theatre.

Protazanov early evinced an interest in the theatre and was especially attracted by the glamour of the actors who frequented the Vinokurov residence (where the Protazanovs lived) since several relatives were in the ‘business’.9 And yet, despite the somewhat eccentric cast to this merchant family, there seems to have been no question that Protazanov would attend any school other than the Moscow Commercial School, though his interests and inclinations lay in other areas. After graduating from the school in 1900, he apparently hoped to enter the Petersburg Technical Institute to study engineering, but some reversals in family fortunes forced him to work in an office instead.

This experience as a wage earner was so disagreeable that Protazanov noted in his own brief memoirs that he was looking for the first opportunity to escape from ‘slavery’. The opportunity finally came in 1904 when he received a 5,000 rouble inheritance from his father’s aunt. Protazanov left the country in June 1904 and did not return permanently until 1907. With his characteristic dry humour he observed that ‘I didn’t finish with slavery, but I did finish off my inheritance very quickly.’10

Protazanov travelled all over Europe, but it was his trip to Paris that altered the course of his life. While there, he added the Pathé studio, centre of pre-war European cinema, to the standard tourist itinerary. To the surprise (and even horror) of his family and friends, Protazanov fixed suddenly and irrevocably upon movie-making as his career of choice. Yet, given his background and character, cinema held obvious attractions.

Protazanov was something of a rebel, chafing at the strictures of the office job to which he had been assigned by family tradition. Given that he was apparently little interested in politics (as demonstrated by his European junkets during the Revolution of 1905–7), the revolutionary road that served so many of his generation did not attract him as an outlet for rebellion.11 At the turn of the century movies were considered a bastard ‘art’ and film-making was an outré profession, if one even dared to call it a profession. It offered Protazanov the opportunity to thumb his nose at his respectable family, throw off the chains of his regimented job, and indulge in his interest in theatre. That cinema held out the promise of making a great deal of money while having a good time also attracted him to film but, given the course of his career, one should not overemphasise this point.12

Moscow’s infant film industry was centred in the merchant district around Pyatnitskaya Street. Although it was dominated by foreigners, Russian entrepreneurs were involved as well, and in 1907 Protazanov went to work for the Russian-armed ‘Gloria’ film studio as an interpreter for a Spanish ‘cameraman’ who knew French (Protazanov’s language of expertise) about as well as he knew how to operate a movie camera. ‘Gloria’ quickly failed, and Protazanov offered his services to the more established concern of Thiemann & Reinhardt.13 He again worked as an interpreter for the cameraman, this time an Italian, who did not speak French but, unlike the Spaniard, did know his business. Protazanov quickly learned all aspects of movie-making as Thiemann & Reinhardt’s jack-of-all-trades. In 1909, he began writing scripts and acting in small parts, and in 1911, when he married the sister of ‘Gloria’s’ former owner, Thiemann raised his salary from fifty to eighty roubles a month. His ‘break’ came in 1911, when he dashed off a script called A Convict’s Song [Pesn’ katorzhanina],which he sold to Thiemann for twenty five roubles.14 The film, Protazanov’s directional début, was a rousing success. As a result Protazanov found himself promoted to director and earning 400 roubles a month.

The production practices that Protazanov developed in his pre-Revolutionary career and continued in the Soviet period reflect early developments in the Russian industry. Perhaps most important was the close relationship that existed between Russian theatre and cinema. Many early Russian movie directors came to cinema from theatre—Vladimir Gardin (with whom Protazanov had frequently collaborated), Pyotr Chardynin and Yevgeni Bauer, to name only a few. Similarly, actors and set designers moved from theatre to film and back, depending on where the jobs were. Throughout his long career in the movies, Protazanov preferred to use actors with theatre training and to hire production personnel he had known in the pre-Revolutionary cinema. In the Soviet period, where breaking with the past in general and the theatre in particular was part of the radical credo, this proved an especially sore point.

Protazanov enjoyed an excellent working relationship with actors, was an astute judge of talent, and cast his pictures well. His ability to attract actors of the stature of Ivan Mosjoukine [Mozzhukhin], Nataliya Lisenko, Vera Kralli, Olga Gzovskaya and Vladimir Maximov doubtless contributed to the popularity of his pre-Revolutionary movies with a public which had heard of these stars but could not afford to attend the theatre.15 He did not depend exclusively on established names, however, and gave Olga Preobrazhenskaya, then a little-known actress from the provincial stage deemed ‘too old’ for major roles, the chance that made her a star.16

Protazanov came to be known for his screen adaptations of famous literary works. The film industry has since its earliest days turned to print literature as a handy source for proven story-lines. In the Russian cinema, adapting ‘great works’ to the screen was especially popular, since the classics lent an aura of respectability to a form of entertainment that might otherwise have been a shade too vulgar for the bourgeois audiences the studios hoped to attract. (In Russia, as elsewhere at this time, the urban middle classes were the chief filmgoers.) Protazanov directed his share of these lavish costume dramas and screen adaptations, the best-known being his mammoth version of War and Peace [Voina i mir, 1915, with Gardin] and The Queen of Spades [Pikovaya dama, 1916].17

But the film that placed Protazanov at the forefront of Russian film directors did not bring a serious work of literature down to the lowly screen; it was instead an adaptation of one of the most popular works of Russian boulevard fiction, Anastasiya Verbitskaya’s sensational novel of illicit miscegenistic love, The Keys to Happiness, made in 1913. Protazanov’s instinct for the entertaining was an unerring as his instinct for the cinematic, and The Keys to Happiness was a legendary box-office success. It was sold out for days in advance and attracted an audience that had never before attended the movies. At ten reels, in two parts, this film was four to five times longer than the typical movie of the day and demonstrated to the Russian studio heads that lengthy movies could sustain audience attention. In direct response to the phenomenon of The Keys to Happiness, Thiemann & Reinhardt established its famous ‘Golden Series’ of full-length feature films, mainly directed by Protazanov.18 Although Protazanov continued making movies based on the classics, his biggest hits were usually derived from popular fiction. It is not surprising that these enjoyed great success with audiences, which as mentioned above were drawn largely from the middle classes—especially from the petty bourgeoisie, which also formed the market for this fiction.19

The outbreak of the First World War scarcely affected the pace of his production: he completed nineteen pictures in 1914; twelve in 1915; and fifteen in 1916. As late as 1917, he managed eight, including the notorious Satan Triumphant, a film about demonism apparently so lurid that Soviet histories of the Russian film gloss over it.20 The war did, however, affect his studio, as the German’ firm of Thiemann & Reinhardt was attacked by mobs. In 1915, after making War and Peace for the ‘Golden Series’, Protazanov left Thiemann to join the Yermoliev studio; like Protazanov, Iosif Yermoliev was the scion of a Moscow merchant family but the princely 20,000-rouble salary that Yermoliev promised probably influenced Protazanov more than did class solidarity.21 The fact that he was drafted at the end of September 1916 and remained in uniform at least until the end of February 1917 was of so little import that neither Protazanov nor his friend Aleinikov bother to mention it when discussing the director’s work during this period22.

After the February Revolution, the Yermoliev studio adjusted to the new Revolutionary mentality and began producing works on Revolutionary themes. Protazanov adapted as well and in 1917 made two films on Revolution in quick succession: Andrei Kozhukhov and We Don’t Need Blood [Ne nado krovi] (about Sofiya Perovskaya). More to his taste, certainly, was his adaptation of a story which he had wanted to film for some time, but which the pre-Revolutionary censors had suppressed as a movie script—Tolstoy’s Father Sergius [Otets Sergii, 1918]. This picture, starring Ivan Mosjoukine as the tsarist officer who becomes a monk, was one of the most important movies to appear immediately after the October Revolution.23

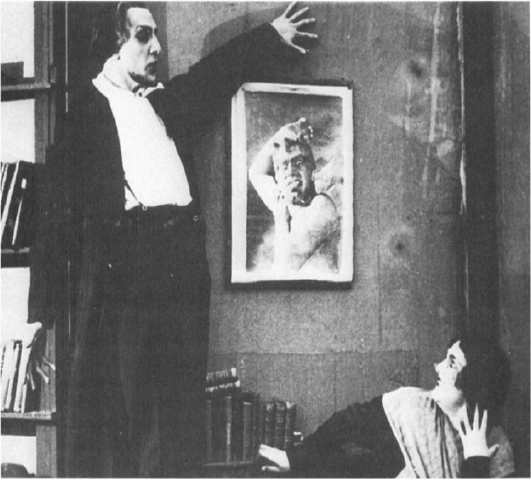

Figure 11 Satan Triumphant [1917] gave Protazanov’s regular stars Mosjoukine and Lisenko a rare opportunity for Expressionist acting in this account of Satan causing havoc in a devout Scandinavian community.

In the winter of 1918–19, Yermoliev became alarmed at the direction the Revolution was taking and concerned for the health and safety of his company in cold and hungry Moscow. He persuaded the entire group, including Protazanov, to move with him to Yalta and set up shop there. The Yermoliev studio’s sojourn in Yalta was a short one, and at the beginning of February 1920 the troupe was again on the move, this time ending up in Paris.24 That 1920 was a bad year for Protazanov is best demonstrated by noting that it was the first since 1909 that he did not add a single production to his filmography, though he had been working under less than ideal conditions for some years.

Professionally speaking, Protazanov effortlessly adjusted to émigré life. A Francophile since childhood, he spoke French fluently and, as previously mentioned, had lived in France as a young man. From 1921 to 1923 he made six movies, five in France and one in Germany. By the time Aleinikov contacted him in Berlin, Protazanov had joined the ranks of established European directors.25 There can be no doubt that Protazanov, like so many of the other Russians from the Yermoliev and Khanzhonkov studios, could have had a successful career in exile in the West. It is not clear, therefore, why the maker of The Keys to Happiness and Satan Triumphant chose to return to Soviet Russia, abandoning a lucrative European career. This decision would seem to give the lie to his own assertion that money was one of cinema’s chief attractions for him.

In any case, he skilfully charted an independent course once back, demonstrating yet again his tough-mindedness and adaptability in the face of adversity. A cursory glance at his ten Soviet silents reveals an oeuvre in keeping with the topical concerns of Soviet society in the 1920s (with the possible exceptions of The Three Millions Trial [Protsess o trekh millionakh] and Ranks and People [Chiny i lyudi]).

In 1924, he made Aelita, a science-fiction fantasy about a proletarian revolution on Mars, very loosely based on Alexei Tolstoi’s novella; in 1925, His Call [Ego prizyv], an adventure melodrama incorporating the theme of the ‘Leninist enrolment’ in the Party, and The Tailor from Torzhok [Zakroishchik iz Torzhka], a comedy both about the housing shortage and the state lottery. In 1926, to be sure, he reverted to type with The Three Millions Trial, a crime caper set in Italy that was one of several film adaptations of Umberto Notari’s play The Three Thieves. But he returned to more typically Soviet subjects in 1927 with The Man from the Restaurant [Chelovek iz restorana], an updating of Ivan Shmeliev’s 1911 novella about a downtrodden waiter who saves his daughter’s virtue; and especially with The Forty-First [Sorok pervyi], from Boris Lavrenev’s popular novella about the Red Army sharpshooter who kills her ‘White’ lover.

In 1928, Protazanov released two pictures: The White Eagle [Belyi orel], a controversial adaptation of Leonid Andreyev’s story about a provincial governor who orders his troops to fire on civilians during the 1905 Revolution, and Don Diego and Pelageya [Don Diego i Pelageya], a fresh and witty comedy attacking the excessive bureaucratism of Soviet society. His final silent productions were Ranks and People [1929], drawn from three of Chekhov’s slightest short stories, and The Feast of St Jorgen [1930], an anti-religious comedy which, although adapted from the work of the Danish writer Harald Bergstedt, was commissioned as part of the campaign against religion taking place at the time. These ten films conformed to generally accepted standards of narrative realism; they featured clearly delineated and believable heroes and villains; and for the most part, they were fast-paced and entertaining. Protazanov worked quickly and efficiently; unlike many of his younger Soviet colleagues, he knew how to finish a film on time and within budget.26 His movies made money and were popular with audiences, at least in the major cities, where movie theatres were concentrated.

And yet Protazanov and his films were frequently subjected to a barrage of criticism from reviewers and from other film-makers throughout the decade. This can be attributed in part to perception, to the fact that he symbolised the ‘Golden Series’.27 In order to understand Protazanov fully, we need to examine his films and their reception in more detail, to situate them in the context of the cultural politics of the era. Recognising the inevitable errors of oversimplification, the cultural politics of the film industry in the mid-1920s can be briefly summed up as a struggle between young and old; between avant-gardists (the ‘montage school’) and realists; between those who inclined toward permanent revolution and those who favoured ‘socialism at a snail’s pace’.28 Fellow-travellers and bourgeois specialists like Protazanov charted a course that was truly between Scylla and Charybdis. The one issue that most politically conscious film activists could agree on was the need to create a totally new Soviet cinema, one which would end the influence of the ‘pernicious’ foreign films beloved of Soviet audiences.29 How to go about creating this new Soviet cinema was quite another matter, and three broad approaches to the problem can be delineated.

Once again acknowledging the oversimplification of this division, we can none the less say that the avant-garde believed that their obligation to society was fulfilled by creating the art of the future; under the cultural and social transformation engendered by socialism, the masses would be uplifted and thereby able to enjoy and appreciate hitherto ‘inaccessible’ art.30 The artistic right, on the other hand, may be characterised as narrative realists. This group was less diverse than the avant-garde, so it is possible to identify two subgroups splitting along political lines. The proletarian ‘watchdogs’ —especially critics connected with the All-Russian Association of Proletarian Writers [Vserossiikaya assotsiyatsiya proletarskikh pisatelei] (VAPP) and the staff of the film section of Glavpolitprosvet, the Main Committee on Political Education in the Commissariat of Enlightenment—favoured a tendentious kind of realism, either narrowly political fictional films or strictly educational kulturfil’my. In sharp contrast, the Commissar of Enlightenment Anatoli Lunacharsky—husband of a film actress and himself author of several entertaining film scripts as well as many articles and even a book on film—believed that there was nothing especially anti-Soviet about entertainment.31 Lunacharsky felt that the goal of Soviet cinema should be to make Soviet films (focusing on melodramas, adventures and comedies) to entertain the Soviet people. This was the line vigorously pursued by the state film trust Sovkino and the semi-independent studio for which Protazanov worked, Mezhrabpom.32 To the proletarians, this brand of cinema realism was tantamount to counter-revolution and was no less dangerous than the ‘Formalist’ heresies preached by Eisenstein, Vertov and many others.

These debates were taking shape as Protazanov set to work in February 1923 on his first Soviet film, the science-fiction fantasy Aelita, the tale of a Soviet engineer who dreams of building a spaceship, taking off for Mars, and falling in love with a Martian princess named Aelita. Because this dream includes a ‘proletarian’ revolution on Mars, Protazanov was able to exercise his talent for adventure and fantasy in a movie with a Soviet theme and, in its terrestrial part, a contemporary Soviet setting.

The production history of Aelita indicates that Protazanov prepared for his Soviet début with great care and forethought. Though schooled in the break-neck pace of pre-Revolutionary film-making, averaging more than ten films annually before the Revolution, he took over a year to complete Aelita. According to the handsome programme that was distributed at screenings of the picture, Protazanov shot 22,000 metres of film for the 2,841-metre movie (an unusually high rate of waste) and employed a cast and crew of thousands.33

This cast and crew was certainly one of the most impressive ever assembled in the 1920s for a single picture. Fyodor Otsep, the head scenarist, and Yuri Zhelyabuzhsky, the cameraman, had had considerable pre-Revolutionary filmmaking experience. Although Protazanov’s Russian films had not been noted for their external decorativeness (that being the hallmark of Yevgeni Bauer, whose work Protazanov disliked), Protazanov paid tribute to new artistic trends by having Alexandra Exter and Isaak Rabinovich design for the Martian scenes the Constructivist costumes and sets for which the movie is famous. The casting was stellar and, according to Protazanov’s custom in his Russian work, drawn almost exclusively from the ranks of theatre actors. The troupe included the director Konstantin Eggert, Vera Orlova, Valentina Kuindzhi, Olga Tretyakova and Nikolai Tsereteli, and introduced to the screen Igor Ilyinsky, Nikolai Batalov and Yuliya Solntseva. Ilyinsky and Batalov became the leading male stars of Soviet silent cinema, and Solntseva enjoyed a following as well.34

The promotional campaign was as lavish as the production itself: in the provincial city of Voronezh, for example, aeroplanes dropped thousands of leaflets advertising Aelita.35 Protazanov intended to make his presence felt in his Soviet début: the director of The Keys to Happiness had returned! Aelita did cause a sensation but not quite the one that the Mezhrabpom studio and Protazanov had hoped for.

No other film of early Soviet cinema was attacked as consistently or over so long a period as Aelita. From 1924 to 1928, it was a regular target for film critics and for the many social activists who felt that the film industry was not supporting Soviet interests. This lively movie that the British critic Paul Rotha labelled ‘extraordinary’, though theatrical, was greeted quite differently in the pages of the Soviet film press. Kino-gazeta, a relatively moderate newspaper, was unrelenting in its opposition to Aelita, going so far as to label it ‘ideologically unprincipled’ and to warn that the potential danger of a ‘rallié’ like Protazanov might outweigh the benefits of his experience and professionalism.36

These criticisms were echoed elsewhere, especially (but not exclusively) in proletarian’ circles. Proletarskoe kino claimed Aelita had cost too much; another newspaper with a proletarian orientation, Kinonedelya, attacked Aelita’s scriptwriters as individuals ‘alien to the working class’ and advised that the Party keep bourgeois specialists like Protazanov under close watch.37 But the following examples, similar in tone, came from varying sources. Viewers in Nizhni Novgorod allegedly criticised its ‘petty-bourgeois’ [meshchanskii] ending and complained that the hardships of the Civil War years were absent from the film;38 to the young director Lev Kuleshov, Aelita exemplified ‘the blind alley of pre-Revolutionary cinema’. Prominent critic Ippolit Sokolov, a supporter of the entertainment film, deemed Aelita too complicated for viewers to understand: Soviet in content but not in form, and ‘too Western’.39 As late as 1928, Aelita was still brought forth as an object of scorn (admittedly, this was in the pages of Mayakovsky’s journal Novyi Lef which resolutely opposed ‘old-fashioned’ entertainment pictures such as these).40

Aelita’s aftershocks jolted Protazanov. Except for his first movie (a 1909 short never released for which he served as scenarist, based on Pushkin’s ‘The Fountain of Bakhchisarai’) every picture he had made had been a critical as well as a popular success. Protazanov learned his lesson well—from this point on, both the style of his films and their manner of production changed to conform to Soviet reality better. He eschewed special effects, expensive sets and fanciful scripts in favour of realistic contemporary films with modest productions (but he never abandoned his preference for seasoned crews and theatre actors, preferably with pre-Revolutionary experience).

Protazanov also reacted to the Aelita ‘scandal’ by resuming a low public profile (although he was once singled out in the press for enjoying a higher standard of living than did other film workers).41 His absence from the debates then raging in the press about actors and acting, plots and scripts, montage, rationalisation of production, etc., while not unique, was noticeable because of his prominence. Perhaps the most amusing example of Protazanov’s practice of keeping close counsel is a two-part series which appeared in Na literaturnom postu. Directors and others prominent in Soviet cinema were called upon to answer several questions about film and literature posed by the journal’s editors. Sergei Eisenstein’s response to the three questions was about 1,300 words; Protazanov’s, exactly 84. Yet his attitude towards his critics was quite clear:

I like to read literary criticism because it doesn’t criticise me. For that reason, I read film criticism with less pleasure.

Igor Ilyinsky relates another example of Protazanov’s extreme reluctance to speak on the record. During the filming of The Tailor from Torzhok, a reporter attempted to interview Protazanov on film genres. The question ‘Which genres do you prefer?’ elicited from Protazanov: ‘In my opinion, all genres are good except boring ones’, but the reporter thought the director was joking. He pressed on, asking Protazanov ‘Which comedies, in your opinion, are needed by the Soviet viewer?’ When Protazanov replied, ‘The Soviet viewer needs good and varied comedies’, the reporter realised there would be no interview and left.42

Despite Protazanov’s recognition that he was living in a new world and despite his ability to make good films in different genres on different subjects, content continued to pose problems for him (as it did for many other directors) because of rapidly changing cultural politics. From 1925 to 1929, his movies can be divided into two groups: the ‘good’ films: His Call, The Forty-First, and Don Diego and Pelageya; and the ‘bad’: The Tailor from Torzhok, The Three Millions Trial, The Man from the Restaurant and The White Eagle. (For reasons that will be discussed below, The Feast of St Jorgen and Ranks and People did not attract the unwelcome attention they might have earlier.) Whether knowingly or not, Protazanov alternated between making films which his critics found acceptable and those which they found unacceptable. Though the critical reception of his films might be unpredictable, their public reception was quite predictable, and Mezhrabpom was much more concerned with box-office success than with ‘critical’ acclaim.

His Call [1925], The Forty-First [1927] and Don Diego and Pelageya [1928] baffled Protazanov’s opponents and help explain his survival during the Cultural Revolution. How could the director of Aelita have made ‘truly Soviet’ films such as these? His Call appealed immediately to Soviet audiences and appeared on a ‘top ten’ list in 1925.43 In His Call, Protazanov succeeded where other Soviet directors had not—he had made an entertaining but indubitably ‘correct’ film about Soviet life.

The melodrama begins in the final days of the Revolution; a rich industrialist and his son Vladimir (Anatoli Ktorov, who was to become a favourite of Protazanov’s) hide some of their fortune before fleeing abroad. Although Protazanov dwells with obvious pleasure on the scenes of their lavish life in Paris, he took care to contrast this ‘decadence’ with the suffering that Soviet citizens, especially children, were simultaneously undergoing. Several years after the Revolution, the pair has spent all their money, and so Vladimir returns to Soviet Russia to retrieve the cache, enlisting a kulak as his accomplice. Young Katya (Vera Popova, from the Vakhtangov Theatre) and her grandmother (Mariya Blumenthal-Tamarina, a famous stage actress) now occupy the room where the treasure was stashed. Katya, attractive but very naive, is easily seduced by the depraved Vladimir. Quick to resort to violence despite his successful seduction, Vladimir murders Katya’s grandmother in his desperate efforts to retrieve the gold. He ends up, fittingly, with a bullet in the back. In the meantime, Lenin has died, and the Party has issued its ‘call’ for new members, dubbed the ‘Leninist enrolment’. The ‘fallen woman’ Katya hears the call but, unworthy to join the Party’s ranks, resists it. Eventually she is convinced that joining the Party will redeem her sins. His Call had everything social critics wanted—contemporary subject-matter and precise details of everyday life, and everything the public wanted—love, violence and a happy ending. The usually dour reviewers could find little about which to complain.44

Protazanov repeated this formula for success (Soviet subject+melodrama+love interest) in The Forty-First. He transformed Boris Lavrenev’s somewhat wooden novella into a memorable picture that, like His Call, was quite entertaining. The plot of The Forty-First is high melodrama: a Red Army sharpshooter, Maryutka (played by the engaging Ada Voitsik, then a student at GTK, the state film institute) and the White officer who is her prisoner (Ivan Koval-Samborsky from the Meyerhold Theatre) are stranded on a desert island after a storm. Once on the island, separated from the rest of her Red Army company, Maryutka falls in love with the young aristocrat, and the story becomes a kind of reverse ‘Admirable Crichton’ until the point of rescue. Maryutka, mindful of her duty as a Bolshevik, claims her lover as her forty-first victim. Is this her victory as a Bolshevik or her defeat as a person?

The Forty-First made the ‘top ten’ chart in 1928, listed as the third-most-popular film.45 But in 1927 (the year of the film’s release), critics were much more cautious than they had been two years earlier when His Call appeared. Although The Forty-First was generally quite well received,46 there were some disquieting notes that portended problems soon to come. ‘Arsen’, one of the most censorious of the new breed of ‘hard-line’ critics, labelled it a ‘socially primitive’ and ‘decadent’ example of the ‘Western adventure’ picture, all the more ‘dangerous’ because it was so well done.47 Fortunately for Protazanov, Arsen’s view of The Forty-First was in the minority.

The final movie to be discussed among the triad of ‘good’ films, Don Diego and Pelageya, is arguably the finest Soviet comedy of the 1920s. Based on a feuilleton by Bella Zorich called ‘The Letter of the Law’ which appeared in Pravda,48 Don Diego and Pelageya is the story of an old woman’s unwitting attempts to circumvent Soviet power, personified by ‘Don Diego’, a foolish daydreamer who is the village station master. Don Diego (Anatoli Bykov) arrests Pelageya (Mariya Blumenthal-Tamarina) for illegally crossing the railroad tracks, despite the fact that she could not read the warning sign.

After a farcical trial, she is sentenced to three months in jail. Enter the Party; two members of Komsomol (the Communist Youth League) and the local Party secretary come to the rescue of Pelageya and her bewildered husband. Protazanov’s depiction of provincial life is scathing and very funny indeed, revealing much about the problems of Soviet society: peasants are more than a little mystified by the ideals and goals of the Revolution, and tsarist chinovniki have been replaced by rigid, lazy and insolent Soviet apparatchiki. This movie, which coincided with the campaign against the ‘bureaucratic deviation’, demonstrated that it was possible to make a topical movie that could transcend the concerns of the moment and entertain at the same time.

Don Diego and Pelageya enjoyed widespread praise as a fine example of what the film comedy (a notoriously weak genre in Soviet cinema) could and should be. But film critics, whatever their stripe, were nervous in 1928. Some felt compelled, therefore, to assert that the role of the Party in solving problems had been insufficiently developed, and that the great evil of bureaucratism had been too individualised in the unlikely person of Don Diego. Despite these reservations (and a fear that the film might be edited abroad in an unflattering fashion) Don Diego and Pelageya was justly hailed, most concurring with A. Aravsky’s assessment that the film was a ‘great event’ in the development of Soviet comedy.49

The pictures that critics considered reasonably ‘good’ were well-made films, popular with viewers, which demonstrated Protazanov’s increasing mastery over the medium. Among his ‘bad’ pictures—that is, those that came under heavy critical fire—The Tailor from Torzhok [1925] is the least interesting. Although it features the popular comic actor Igor Ilyinsky, The Tailor is a slight comedy. Petya (Ilyinsky) needs to retrieve his winning lottery ticket from his landlady, whom he was supposed to marry and with whom he has quarrelled. A poorly integrated subplot, inserted to inject some ‘ideology’ into the farce, concerns the maltreatment of Petya’s true love, Katya (Vera Maretskaya), who is being exploited by her cruel relation, a minor Nepman who owns a shop.

Figures 12, 13 The ‘good’ and the ‘bad’: His Call(top) made a stirring melodrama out of émigrés scheming to recover their wealth at the expense of honest workers, while The Tailor from Torzhok starred Ilyinsky as an innocent provincial trying to recover a winning lottery ticket from his scheming landlady.

Modest though it was, The Tailor from Torzhok obviously struck a responsive chord with Soviet audiences, since it recorded a healthy profit only two months into its run.50 Critics like Khrisanf Khersonsky (an intelligent, generally moderate, critic who enjoyed movies), on the other hand, found the picture only sporadically funny and the character of the tailor ‘alien’.51 Nevertheless, The Tailor escaped any serious opprobrium until the Cultural Revolution: Protazanov was still reaping the benefits of His Call.

His next comedy, The Three Millions Trial [1926], was a different matter. More ‘bourgeois’ in setting and style than just about any other film of Soviet production, The Three Millions Trial is a sophisticated crime comedy-adventure that is virtually indistinguishable from Western productions of the era. Among the movies shown Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks when they visited Moscow in 1926, The Three Millions Trial alone garnered no praise from the stars, the absence of which was noted in the press.52

Yet The Three Millions Trial does have a ‘class-conscious’ theme. It concerns a banker who has sold his house for three million so that he will have the capital necessary to speculate on food shortages. The famous ‘gentleman thief’ Cascarillia (played by the debonair Anatoli Ktorov), with the assistance of the banker’s lascivious wife Nora (Olga Zhizneva) steals the money, only to have his glory stolen from him by the ‘common thief’ Tapioca (Igor Ilyinsky). Tapioca is arrested trying to rob the banker’s house, and the police assume that he took the three million. Since no one can imagine where the fortune is, Tapioca becomes a folk hero for having outsmarted the police. Unable to stay out of the limelight, Cascarillia dramatically appears at Tapioca’s trial and tosses the three million to the wildly cheering crowd.

Despite the didactic potential of the theme, this stylish film was played for entertainment value, so it is not surprising that 90 per cent of audiences surveyed liked it. (Fairbanks and Pickford, expecting to see ‘revolutionary’ Soviet films, naturally found it unremarkable.) The public embraced The Three Millions Trial wholeheartedly and, like His Call and The Forty-First, the picture made a ‘top ten’ list.53 Since Soviet audiences preferred European and especially American movies, it was quickly recognised that The Trials popularity was largely due to its resemblance to Western films (namely its genre, ‘Western-adventure’, and its emphasis on sex and greed)—as well as to the phenomenal popularity of Ilyinsky (who was reprising the role he had created for the Kommissarzhevsky Theatre’s adaptation of the same story).54 Even Sergei Eisenstein, who did not much concern himself with Protazanov, singled out The Three Millions Trial as an exemplar of the ‘Western-local’ film that was in his opinion anathema to a revolutionary cinema.55

Though The Tailor from Torzhok and The Three Millions Trial were criticised fairly harshly, they had escaped lightly compared with The Man from the Restaurant [1927] and The White Eagle [1928]. Both pictures represented Protazanov’s return to melodramas on revolutionary themes but, unlike His Call and The Forty-First, they lacked adventure and romance. Protazanov may nevertheless have expected that he could repeat the success he had enjoyed with His Call and The Forty-First.

The Man from the Restaurant takes place in 1916–17 and concerns the social awakening of a poor waiter (played by the Moscow Art Theatre actor Mikhail Chekhov). The waiter’s musically gifted daughter (Vera Malinovskaya) must for financial reasons leave school to play the violin in the restaurant. There she attracts the unwelcome attention of a wealthy industrialist who hopes to make her his mistress. The contrasts between the haute bourgeoisie (greedy, profligate, immoral and cruel) and the proletariat (as depicted by the waiter and his daughter—hard-working, humble, and honest) are sharply drawn. Protazanov’s efforts to evoke the waiter’s growing sense of outrage were apparently sincere, but the film suffers from a number of shortcomings.

The plot and mise-en-scène are laboured and strongly reminiscent of F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh [Der letzte Mann, 1924] which leads to an inevitable and unfortunate comparison. At a time when there was an ever-increasing clamour for a positive Soviet hero, the protagonist of The Man from the Restaurant is far from positive. The waiter is so tediously humble that the picture lacks dramatic focus, a problem intensified by Chekhov’s mannered and theatrical performance. Moreover, the waiter’s ‘political’ transformation seems to spring from purely personal sources: his desire to protect the virtue of his beloved daughter (and his grief over the death of his son at the front). It certainly did not help The Man from the Restaurant’s reception, considering the political climate in 1927, that the plot had been derived from a pre-Revolutionary story by Ivan Shmeliev. (Like Protazanov, Shmeliev was a member of the Moscow kupechestvo who had emigrated to the West; unlike Protazanov, he had not returned.)

In 1927, on the eve of the March 1928 Party Conference on Cinema Affairs which heralded the start of the Cultural Revolution in cinema, the two major studios—Sovkino and Mezhrabpom-Rus—found themselves under heavy fire. The Man from the Restaurant, along with The Tailor from Torzhok and The Three Millions Trial, became ammunition in the assault on Mezhrabpom.56 The Man was specifically attacked, over and over, as too theatrical and ‘reactionary’.57

When The White Eagle was released, the Cultural Revolution was definitely under way. While the film is flawed, it illustrates that Protazanov was not—as his critics often charged—a ‘formula’ film-maker; certainly he was not the ‘epigone of Khanzhonkovshchina’ that Sergei Tretyakov (an opponent on the artistic left) claimed.58 The White Eagle is an adaptation of Leonid Andreyev’s story about a provincial governor during the Revolution of 1905. The governor (V.Kachalov) orders troops to break up a street demonstration by firing on a crowd and three children are among those killed in the ensuing mêlée. Rewarded for his success at crowd control with the Order of the White Eagle, the governor is tormented by his bad conscience, and his struggle to come to terms with his deed is the crux of this psychological drama. The corollary to the governor’s angst is that of the governess-cum-revolutionary (Anna Sten), who cannot bring herself to assassinate the governor, although she is convinced that it would be just retribution for the massacre.

The American critic Dwight MacDonald admired the film enormously, going so far as to call Kachalov’s performance ‘the high-water mark of movie acting’,59 but his opinion was assuredly not shared by his Soviet contemporaries, at least by those who went on record about the film. The White Eagle was castigated by critics from different points on the cultural-political spectrum for humanising the class enemy’, for being only superficially revolutionary, for being boring (‘like a prison sentence’ to watch), and for making a direct appeal to the petty-bourgeois viewer.60 It was regularly used as a stick with which to beat Mezhrabpom.61

And yet, despite all this, in the darkest days of the Cultural Revolution Protazanov not only avoided a sustained personal attack (a major achieve ment in itself), but he continued to work. No doubt his resolute silence on the burning questions of the decade (regardless of his motivations) served him well. Since he had neither written nor said anything, nothing could be held against him except his movies. While, as we have seen, there was much that the new ‘proletarian’ critics (who eventually took over the cinema press)62 found to dislike in these films, no one had ever charged Protazanov with the crime of technical innovation. It was the ‘Formalists’—the code word for youthful avant-garde directors—who were the chief targets of the Cultural Revolution in cinema.63

Given the political climate, Protazanov’s final two silent films, Ranks and People [1929] and The Feast of St Jorgen [1930], are understandably cautious. Ranks and People, based on three stories by Chekhov (the alternative title was A Chekhovian Film Almanac), represents Protazanov’s return to Russian classics as a source for his films for the first time since Father Sergius. The vignettes stay very close to the stories on which they were based: ‘The Order of St Anne’ [Anna na shee], ‘Death of a Bureaucrat’ [Smert’ chinovnika] and ‘Chameleon’ [Khameleon]. Apart from some fine acting—Ivan Moskvin as the hapless chinovnik whose sneeze leads to his death and Maria Strelkova as the unhappy young woman in a loveless marriage—nothing would indicate to the uninitiated viewer that this film was the work of a major director. Indeed, the mise-en-scène is so unimaginative that it seemed Protazanov had lost his zest for movie-making.

The Feast of St Jorgen, an anti-religious comedy, is much livelier, which is not surprising considering its stars, Anatoli Ktorov and the irrepressible Igor Ilyinsky, who play two escaped convicts masquerading as nuns on a pilgrimage. Ktorov, in a variation of his role as Cascarillia in The Three Millions Trial, is an ‘international thief’ by the name of Corcoran who seizes the unexpected opportunity to claim the pretty ‘bride’ (Mariya Strelkova) who each year is chosen for the saint on his feast day. Corcoran sheds his habit and ‘appears’ to the worshipful throng as the saint. The Feast of St Jorgen displays a lighter touch than many films that were part of the campaign against religion, but is only intermittently funny and does not demonstrate Protazanov’s capabilities as well as some of his earlier work.

What distinguishes these ‘neutral’ movies from the ‘bad’ ones (The Tailor from Torzhok, The Three Millions Trial, The Man from the Restaurant and The White Eagle)? To the disinterested observer, Ranks and People’s portrayal of pre-Revolutionary life differs little from that of The Man from the Restaurant, and yet the former picture received only half-hearted criticism for its ‘soft’ portrayal of hard times. The mystery deepens when The Feast of St Jorgen is compared to The Three Millions Trial. The films are quite similar—satires set abroad featuring the type of thief-hero popular in folklore. Yet The Trial was much maligned while The Feast was termed ‘valuable and well-made’.64 How can this difference in critical reception be explained?

It is possible to answer this question by referring to the chaos of the times: much was happening that was ambiguous, confusing and contradictory. But, even as the Cultural Revolution was playing itself out, carrying numerous directors, scenarists and critics into the maelstrom, the outlines of the second phase of post-Revolutionary culture were discernible. This new culture was based on the tenets of Socialist Realism, fulfilling at least in part the programme espoused by the proletarian radicals (simplicity, realism and optimism). But a component that increased in importance and was not part of the ‘proletarian’ platform in the 1920s was its traditionalism. This manifested itself in the arts by the call for a ‘return to the classics’, and by generally trying to re-establish Soviet ties to the Russian past. Protazanov’s films fit these criteria quite well, laying the foundation for an eventual re-evaluation of his work.

In his person and through his art, Protazanov carried on the bourgeois tradition of Russian cinema. With varying success, Protazanov infused his Soviet films with a ‘Westernised’ version of Russian style. Exploring the differences in reception between Protazanov’s films like The Three Millions Trial and The Feast of St Jorgen sheds some light on the Cultural Revolution’s impact on cinema, but more revealing to the larger issues under consideration here are the differences between the movies that were well-received critically and those that were attacked.

All Protazanov’s pictures are realistic. Story development was not an area of particular strength, but his plots are always easy to follow, with enough action to engage the viewer. He excelled in characterisation and casting, a key in understanding the popularity of his films with a public already in love with Western stars like Fairbanks and Pickford. Soviet audiences, not surprisingly, responded best to the movies that were lively and amusing: His Call, The Forty-First, Don Diego and Pelageya, The Tailor from Torzhok and The Three Millions Trial. As we have seen, critics liked the first three, but not the last two, claiming with considerable disingenuity that these judgements had to do with relative social and political impact. Protazanov was always willing to tell an ideologically acceptable story if it were entertaining; from watching these films, it is clear that what counted for him was the characters, not their ideology (or lack of it).

The Tailor from Torzhok and The Three Millions Trial are not anomalies in Protazanov’s work any more than are His Call, The Forty-First and Don Diego. Given these parameters, how does one situate The Man from the Restaurant and The White Eagle in this oeuvre? By the late 1920s, due to the rapidly changing political climate, audience reactions to movies rarely appeared in the press, but both films are so relentlessly downbeat that it is hard to imagine lines at the box office.65 Yet both these films, and certainly The White Eagle, demonstrate that, in his own unspectacular way, Protazanov was willing to take the risks that all true artists need to take to advance their art and grow creatively, despite the perception that he was a director who cared only for box-office success.

While there can be little doubt of Protazanov’s popularity with the mass audience in the 1920s, he was held in very low repute by another audience that cannot be lightly dismissed: Soviet critics, especially those critics who rejected film as entertainment. Their point of view was summarised by B. Alpers in his review of The Feast of St Jorgen, which he, unlike others, disliked. Alpers attacked Protazanov as a master at making superficially Soviet films that enjoyed widespread appeal due to their ‘social neutrality and external decorativeness’. He admitted that Protazanov knew how to craft films so well that they held one’s attention, a talent Alpers found deplorable. Alpers charged the director with adhering to the ‘traditional’ path, a path which he awkwardly described as ‘balancing on a thin and swaying tightrope of shallow entertainment’.66 Yet, significantly, Alpers’ opinion was echoed by critics much more talented than he. Viktor Shklovsky, who wrote the screenplays for The Wings of a Serf [Kryl’ya kholopa, 1926], By the Law [Po zakonu, 1926] and Bed and Sofa [Tret’ya Meshchanskaya, 1927] (among many others), called Protazanov a representative of ‘the old cinematography of the European type, a little out-of-date’. Adrian Piotrovsky, artistic director of the Leningrad studio and friend of the avant-garde, saw Protazanov as the head of the reactionary ‘right deviation’. Even a supporter and practitioner of the entertainment film like Commissar of Enlightenment Anatoli Lunacharsky called Protazanov a good director, but ‘not of our time’.67 The times, however, were changing in a way that favoured Protazanov.

Yakov Protazanov made six more movies in the last fifteen years of his life and completed his final film in 1943, two years before his death in 1945 at the age of 64. The best known of these was his handsome 1937 adaptation of Ostrovsky’s play Without a Dowry [Bespridannitsa]. While his absolute rate of production declined, the total of his films is comparable to the output of other directors at this time. The decline represents the slow recovery of cinema after the havoc wrought by the Cultural Revolution and the coming of sound.

Protazanov’s legacy extends beyond his impressive body of work, the sum of which proved to be greater than any of the parts. First, he provided an element of historical continuity to the Soviet film industry; the importance of this link with the Russian past became more evident as revolutionary fervour subsided, and Stalin sought to emphasise stability and continuity. The cultural values and tastes of the educated, Westernised bourgeoisie remained a strong influence on early Soviet society through the works of Protazanov, Vladimir Gardin, Alexander Ivanovsky, and Cheslav Sabinsky and, of course, their very popularity attested to the vitality of this taste and culture.

Figure 14 The classic Ostrovsky play Without a Dowry provided Protazanov with a safe yet ideal showcase for his talents in 1937.

Second, Protazanov kept alive the tradition of the narrative entertainment film, which in its dramatic and comedic forms enjoyed great public popularity. Even in the darkest days of the Stalinist era, this tradition was carried on, especially in the work of Grigori Alexandrov, who much admired Protazanov.68

Third, Protazanov was responsible—along with Fridrikh Ermler, a director of proletarian origin—for returning the actor to a place of importance in Soviet cinema; present-day Soviet cinema is known for its exceptional acting talent, not for its technical innovations. Unlike Ermler, whose pistol was his method of persuasion on the set, Protazanov was the complete professional, whose skills and tact have been attested to by a generation of Soviet actors.69

Fourth, Protazanov proved that well-made entertainment films did not require huge outlays of time and material. Aelita aside, Protazanov’s movies were often held up to the younger generation as examples of how much an experienced director could accomplish with very little. Don Diego and Pelageya [ 1928] was completed in three months at a cost of only 40,000 roubles, whereas Vertov’s documentary A Sixth Part of the World [Shestaya chast’ mira, 1926] had taken nineteen months and 130,000 roubles.70

Protazanov’s heirs have recognised what many of his contemporaries did not—that he was a director of the first magnitude. Protazanov has been honoured with two editions of Aleinikov’s Festschrift, by Arlazorov’s biography, and by favourable notices in all the standard film histories.71 The attitude of this succeeding generation towards Protazanov is exemplified by N.M.Zorkaya, who has stated:

Without institutes and surveys, he empathised with the viewer and unerringly knew what would work on the screen and what the public would like….

Then, they often complained about the level of his pictures. Oh, if it were possible to reach the Protazanovian level in all of today’s screen productions!72

Protazanov gave a great deal to Soviet cinema, but the influence was very much reciprocal. Speculation on what he might have accomplished if he had remained in the West is beside the point. Back home, Protazanov, though past his first youth, continued to mature as a director and enjoyed a long and fruitful career in the movies. Despite the fact that his work was not obviously influenced by the experiments of his younger contemporaries, I would suggest that the impact of the ferment of the ‘Golden Age’ of Soviet cinema is visible in his best films and that it is not coincidental that his outstanding pictures—Don Diego and Pelageya, The Forty-First and The White Eagle—happened to be those on subjects closely reflecting the issues and concerns of Soviet society in the 1920s.