6

CHAPTER SIX

TEAMS ARE CRITICAL:

ASPIRATION AND MISSION

I slowly put the phone back into its cradle. It was a beautiful spring day and the sun was shining. During the phone call, which lasted about ten minutes, I had sweated through my dress shirt. I had removed my tie about two minutes into the call. On the other end of the call was my client, the VP of marketing at a large retail brand who, after screaming at me for what seemed like hours, calmly informed me that their company was suing our marketing agency for more than $10 million, and it could conceivably rise to $100 million. The problem was a mistake we made on their marketing campaign. So I leaned back, stunned into submission, and pondered exactly how I was going to tender my resignation. I thought, “Why was this happening to me? How did this happen?” Frankly, it was all related to me not knowing how to select, train, and lead a team. Let me explain.

I was hired into the marketing agency about three years earlier in my first professional job. It was a great opportunity. The agency was growing rapidly, I had come out of college late and so I put myself on a fast track. After just three years, I was an account director and a rising star. I worked crazy hours, seventy-five to ninety hours per week; the first year at the agency I worked six to seven days a week, spending weekends learning how to program so that I could do my own custom report queries on several databases that housed our client’s customer data. My personal belief was that all my success would come from my abilities to make it happen. I did not really believe other people were as smart or as competent as me. I truly believed that to get things done right, you had to do them yourself.

So when we landed a large retail brand, I was thinking, “Man, if I get this account right, I am going to get promoted to be a vice president.” And when I was asked to take on this new account and hire a team to run it, I was ecstatic. Then, having never really managed a team before, I proceeded to make every mistake you could regarding hiring, training, and leading one.

First, I hired people like me, but not quite as smart as me, lest I feel threatened. Second, all seven team members reported directly to me, and I micromanaged the hell out of them. Third, I did not let anyone on the team make a decision without my input.

So, in hindsight, it was pretty predictable that my own inability to understand the potential and nature of a great team would lead to a catastrophic mistake. The team, through a series of seemingly small decisions, had created the situation for the error that occurred. But it was my fault. I never trusted the team. They were trying to do the right thing and they made a mistake. But I took the hit. The CEO of the marketing agency taught me a very valuable lesson. He did not fire me. He invited me to his house for what I thought was going to be the grand execution, but instead he spent five hours with me dissecting how the problem happened and, in the process, exposing a key flaw in my management style. The CEO made me understand that my future career success would ultimately come from the fact that everything in business is done by teams. And that great teams do the best work. That night, I vowed to be a leader of great teams.

Amazingly, I actually recovered from this marketing mistake with the retail brand. We found a way to legally remedy the error and we did not get sued. We did lose the account, but we professionally managed it over the next ninety days to successfully transition it to another agency. Nothing brings your ego down to earth like cleaning up your own mess. I continued on at the agency for another four years, built great teams, and achieved even greater success. All without working crazy hours anymore. I’d learned that working “smart” was better than working “hard.”

INDIVIDUALS CAN START COMPANIES,

BUT TEAMS BUILD THEM

If you are wondering why I have a chapter on teams in a book on creativity and innovation, it’s because teams are critical to both. But we don’t really teach people the skill sets related to recruiting, training, and leading a great team. Even in my college-level Creativity and Innovation course, students complain about their project teams all the time. “She does not show up for meetings;” “He does not do so-and-so;” “They don’t like me.” I tell the students the same thing I tell businesspeople I mentor: Get over it. Make your “team work.” It’s life. Teams are never perfect but learning how to manage and lead teams is priceless.

Let’s look at the importance and benefits of teams:

No employee can work alone for long. You have to work with colleagues to accomplish a task efficiently, with each person bringing his or her particular best to bear on the task. Think Apollo 13. It took the astronauts and NASA’s Mission Control working together to get the spacecraft back to Earth. One person didn’t just turn the ship around.

No employee can work alone for long. You have to work with colleagues to accomplish a task efficiently, with each person bringing his or her particular best to bear on the task. Think Apollo 13. It took the astronauts and NASA’s Mission Control working together to get the spacecraft back to Earth. One person didn’t just turn the ship around.

Problems are more easily solved. A single brain can’t always come up with solutions or make decisions. In a team, every team member can contribute varying alternatives that another person might not have struck upon. You can then bring your different points of view to a discussion of the alternatives and come up with the best possible solution.

Problems are more easily solved. A single brain can’t always come up with solutions or make decisions. In a team, every team member can contribute varying alternatives that another person might not have struck upon. You can then bring your different points of view to a discussion of the alternatives and come up with the best possible solution.

Tasks are accomplished more quickly. An individual will definitely take more time to perform if that person is single-handedly responsible for everything. When employees work together, they start helping each other and responsibilities are shared, and thus it reduces the workload and work pressure. Team members can be assigned one or the other responsibility according to their specialization and level of interest, and thus the output is much more efficient and faster. There’s a reason Henry Ford’s assembly line was so successful.

Tasks are accomplished more quickly. An individual will definitely take more time to perform if that person is single-handedly responsible for everything. When employees work together, they start helping each other and responsibilities are shared, and thus it reduces the workload and work pressure. Team members can be assigned one or the other responsibility according to their specialization and level of interest, and thus the output is much more efficient and faster. There’s a reason Henry Ford’s assembly line was so successful.

Work never suffers or takes a backseat. On critical projects, you need to manage your “bus factor.” That is, how many people can get “hit by a bus” before the project comes to a screeching halt. In a team, the other team members can perform and manage the work in the absence of any member and therefore work is not affected much. The team keeps the project moving forward.

Work never suffers or takes a backseat. On critical projects, you need to manage your “bus factor.” That is, how many people can get “hit by a bus” before the project comes to a screeching halt. In a team, the other team members can perform and manage the work in the absence of any member and therefore work is not affected much. The team keeps the project moving forward.

It’s okay for there to be healthy competition among team members. Competition is always good for employees as well as the organization because people feel motivated to perform better than their other team members (or to be perceived as being valuable to the team) and in this way contribute even more to the team. And collectively the team outperforms. On the NHL ice hockey team the Chicago Blackhawks, Jonathan Toews celebrates as much when he scores as when Patrick Kane, his teammate, does.

Teamwork is also important to improve the camaraderie among employees. Individuals who work in close coordination with each other come to know each other better. The level of bonding increases as a result of teamwork. Research shows when team members care about one another, they perform better.

Team members can also gain knowledge more rapidly when they work together than when they work alone. Every individual is different and has some unique qualities and skill sets and knowledge. Each individual can benefit by learning something new from other team members, which would actually help them in the long run. Would there have been a Google if Larry Page had not met Sergey Brin, and how much did they learn from each other working together out of a garage in Menlo Park, California?

Working on a team increases accountability. Peer pressure is a powerful force. Particularly if you’re working with people you respect and don’t want to let down. The motivation to help your team succeed can help you overcome those down days when you’re not at your best.

The lows of a project are more demoralizing when working alone. Sand traps that you struggle to get out of, monotonous work that you need to grind through, and problems that seem to defy all understanding become less draining and more bearable when there’s someone else to share the pain with. And celebrating an achievement with teammates is a great way to boost morale. If you work alone, who are you going to high-five when you get something right?

All of this doesn’t mean that working on or leading a team is easy. We’ve all probably had our share of project experiences where slackers don’t pull their own weight and take the fun out of teamwork. But given the productive results of great teams, you should figure out and practice how to build effective teams.

BUILD YOUR OWN GREAT TEAM

Let’s say you are challenged to building your own great team, whether it’s for a department or a startup company. What does your team look like and what type of people comprise the team? Here’s a sample roster:

The Genius: Expertise is one skill a founding team can’t do without. Often a diva, the genius will challenge the rest of the team and ask for things that the others aren’t sure how to get done. This person is filled with passion and is often considered to be the most high-risk member of the team. Geniuses ask for a lot, and they never settle.

The Genius: Expertise is one skill a founding team can’t do without. Often a diva, the genius will challenge the rest of the team and ask for things that the others aren’t sure how to get done. This person is filled with passion and is often considered to be the most high-risk member of the team. Geniuses ask for a lot, and they never settle.

The Overperformer: The overperformer is the person who gets down to business and accomplishes tasks. From ordering office supplies to keeping the office network running, this person has a combination of eccentricity, nerdiness, and charisma. The genius and the overperformer are often the same type of person. Add this person as early to your team as possible as this personality is nearly impossible to add later. Too disruptive.

The Overperformer: The overperformer is the person who gets down to business and accomplishes tasks. From ordering office supplies to keeping the office network running, this person has a combination of eccentricity, nerdiness, and charisma. The genius and the overperformer are often the same type of person. Add this person as early to your team as possible as this personality is nearly impossible to add later. Too disruptive.

The Team Leader: Running a team or company with more than one founder is a democratic process, but hard decisions that affect everyone need to be made. Consensus usually requires compromise. Every project team or startup needs a clear leader. Leaders aren’t necessarily paid more or have more equity, and they’re not necessarily the CEO. The leader is just someone whom the others look up to and are willing to follow if there is conflict and when tough decisions need to be made.

The Team Leader: Running a team or company with more than one founder is a democratic process, but hard decisions that affect everyone need to be made. Consensus usually requires compromise. Every project team or startup needs a clear leader. Leaders aren’t necessarily paid more or have more equity, and they’re not necessarily the CEO. The leader is just someone whom the others look up to and are willing to follow if there is conflict and when tough decisions need to be made.

The Industry Expert: While departments or startups are often formed around new ideas, it helps to have someone who knows how things are done in the company’s industry. It takes a long immersion in the marketplace to call yourself an insider, to understand the subtleties of the competitive landscape, to recognize people as true assets, and to cut through the “noise” in the industry and clearly see the opportunity. The industry expert has been there, seen it, and knows what to do.

The Industry Expert: While departments or startups are often formed around new ideas, it helps to have someone who knows how things are done in the company’s industry. It takes a long immersion in the marketplace to call yourself an insider, to understand the subtleties of the competitive landscape, to recognize people as true assets, and to cut through the “noise” in the industry and clearly see the opportunity. The industry expert has been there, seen it, and knows what to do.

The Sales Beast: Startups, new departments, or growing companies with brilliant ideas often forget that someone needs to sell something. Having a strong salesperson on the team helps minimize the risk. The combination of technical insight, leadership, and sales experience is a hard-to-beat advantage in a competitive marketplace. This person could seemingly sell anything to anybody at any time. Just make sure this person has a high degree of integrity to go with his or her “beast” sales mode.

The Sales Beast: Startups, new departments, or growing companies with brilliant ideas often forget that someone needs to sell something. Having a strong salesperson on the team helps minimize the risk. The combination of technical insight, leadership, and sales experience is a hard-to-beat advantage in a competitive marketplace. This person could seemingly sell anything to anybody at any time. Just make sure this person has a high degree of integrity to go with his or her “beast” sales mode.

The Financial Nerd: Every project team, startup, or rapidly growing company needs to budget, manage resources carefully, and predict cash flow, which means it needs financial talent. While this might be the easiest personality to add, the financial expert could also be one of the most important people on the team, especially if managing finances is critical to the team’s success.

The Financial Nerd: Every project team, startup, or rapidly growing company needs to budget, manage resources carefully, and predict cash flow, which means it needs financial talent. While this might be the easiest personality to add, the financial expert could also be one of the most important people on the team, especially if managing finances is critical to the team’s success.

TEAM MISSION, ASPIRATIONS, AND RISK ARE CRITICAL

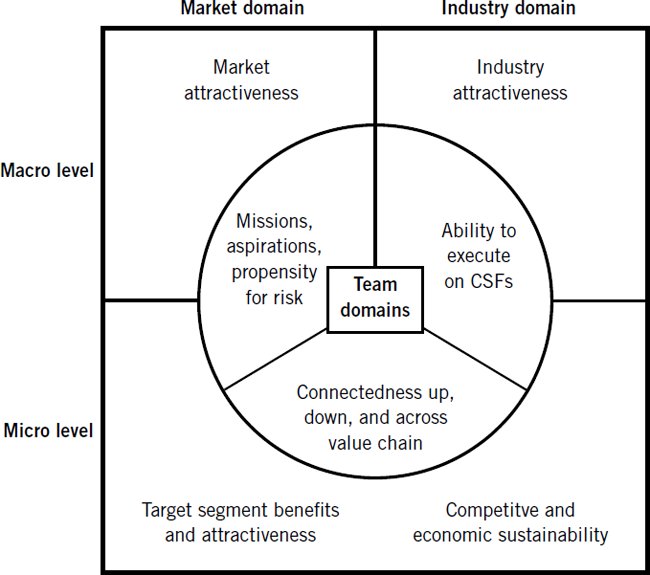

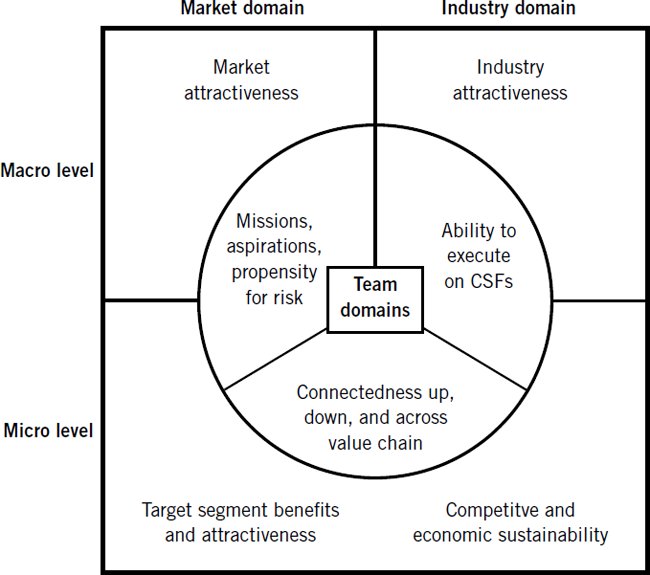

Since learning from the mistakes I made with my first team, I’ve worked with amazing teams for the rest of my career. One tool that can help you build great teams is the three team domains framework from The New Business Road Test, 4th edition, by John Mullins, a professor at the London School of Business and a former entrepreneur. It will enable you to build teams for your department, division, or startup intentionally as opposed to letting them randomly come together.

[MULLINS’S THREE TEAM DOMAINS FRAMEWORK]

Team Domain One: Mission, Aspirations, Propensity for Risk

In this domain, located in the center of Mullins’s model, you are going to analyze commitment—yours and that of your team—to this department, startup, or idea. If it is a startup, think about why you want to start this business. Are you passionate about this idea and, if so, why? What do you want to do with this business? Are you ambitious for it, or do you want it to be a “lifestyle business”? What are your personal goals and values, and how does this venture align with them? And are you prepared to take the risk and put in the hard work needed to build this business? Explore the motivations of your team, too. What are they hoping to achieve and why? Do their motivations align with yours? And are they prepared to work really hard to make the business a success? Money and/or reputations could be at stake if the venture fails, so think about attitudes toward risk within the team.

Team Domain Two: Ability to Execute on Critical Success Factors

You now need to identify the critical success factors (CSFs) for the business or project and think realistically about whether your team can deliver on them. Start by answering these questions:

Which decisions or activities will harm the business significantly if you get them wrong, even when everything else is going right?

Which decisions or activities will harm the business significantly if you get them wrong, even when everything else is going right?

Which decisions or activities will deliver disproportionately high benefits or enhance performance, even if other things are going poorly?

Which decisions or activities will deliver disproportionately high benefits or enhance performance, even if other things are going poorly?

Given the knowledge and skills of the team that you’ve put together, how certain are you that you and your team can deliver successfully on these CSFs? If you see a gap in skills or abilities, who can you bring on board to fill this gap?

Given the knowledge and skills of the team that you’ve put together, how certain are you that you and your team can deliver successfully on these CSFs? If you see a gap in skills or abilities, who can you bring on board to fill this gap?

Team Domain Three: Connectedness Up, Down, Across the Value Chain

This last domain is all about your network and industry connections and how important they are to the success of your business. First, look at your suppliers and potential investors. Who do you know who can supply you with the resources you need to pursue this venture? How good are your relationships with these people? Next, look at your potential customers and distributors. In what ways can you capitalize on your connections here? Last, look across the value chain, including product development, manufacturing, and distribution. Who do you or your network know across the value chain? Do you know any of your competitors personally? If so, how could this relationship help or hinder your venture? And could these people be partners if you thought about them differently?

All too often, when I meet with founding teams or managers of departments in existing companies, it does seem rather random how these teams were created. They seem to be based rather loosely on friendships as opposed to skill sets. While working with your friends can be good or bad, depending on what happens and on the team domain variables, a great team would seem to be one that is put together strategically. Remember, assembling a great team will lead to a higher level of creativity regarding problem solving and potentially innovation.

Let me share another perspective on team “mission” with you, one that I use in my Creativity and Innovation course.

WHAT’S YOUR MISSION?

One thing I have learned in working with creativity and innovation tools/frameworks is that the quality of the team and the pace of the mission are directly correlated to the team’s potential for success. In Silicon Valley, most top venture capitalists (VCs) say, “Give me a great team with a decent or even mediocre idea and they will figure it out. A weak team with a great idea is a recipe for disaster.” In my Creativity and Innovation course, student teams get more done in a demanding forty-five-minute structured brainstorming exercise than if I gave them hours or days to solve the problem. In other words, a team with no deadline or sense of mission tends to become lazy and meandering in solving a problem. A talented and creative team with a limited time frame and looming deadline gets things done with a sense of urgency.

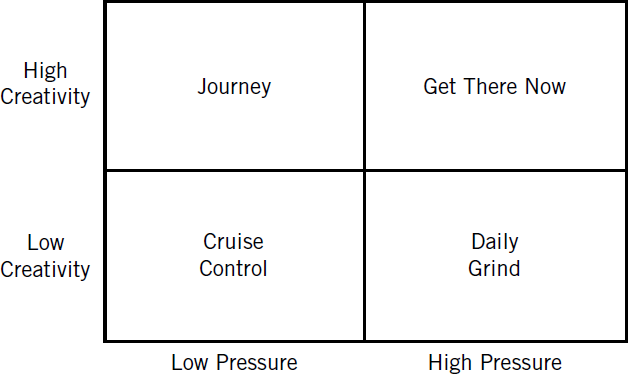

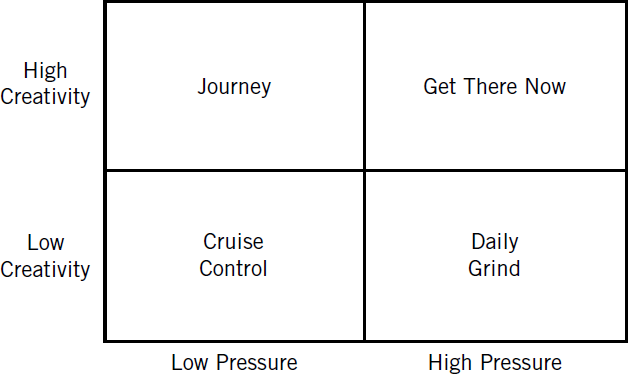

Why are some teams creative and actually push for innovative breakthroughs and why do others go nowhere? Urgency. Let’s look at four types of teams and their potential for creativity based on the “urgency” of their mission and the creative makeup of the team:

[CREATIVITY AND MISSION GRID]

The Cruise Control Mission: Absolutely the worst scenario for potential innovation. There is a low amount of pressure to get anything done, so you end up with a team with low creativity aspirations.

The Cruise Control Mission: Absolutely the worst scenario for potential innovation. There is a low amount of pressure to get anything done, so you end up with a team with low creativity aspirations.

The Daily Grind Mission: This type of team is marginally better than the previous one, with the difference being that the pressure is high for the team to perform perhaps by a certain deadline. The problem is that the team is not very creative, talent-wise, so they feel the pressure but don’t know how to solve the problem. So team members tend to stand still and grind in place.

The Daily Grind Mission: This type of team is marginally better than the previous one, with the difference being that the pressure is high for the team to perform perhaps by a certain deadline. The problem is that the team is not very creative, talent-wise, so they feel the pressure but don’t know how to solve the problem. So team members tend to stand still and grind in place.

The Journey Mission: This team actually has a high amount of creativity, which is awesome, but there’s low pressure to perform, no real deadline, and no end in sight for the project, so team members tend to meander and wander around. The result is several creative starts and stops with no real destination.

The Journey Mission: This team actually has a high amount of creativity, which is awesome, but there’s low pressure to perform, no real deadline, and no end in sight for the project, so team members tend to meander and wander around. The result is several creative starts and stops with no real destination.

The “Get There Now” Mission: This team, with a high amount of creativity and a high pressure deadline, has the highest potential to be both creative and innovative. They may have limited time and resources but they are highly creative, can pivot if necessary, and when facing an imposing deadline, they figure out how to get it done. This is the best possible team; they are highly creative under pressure and when facing a deadline.

The “Get There Now” Mission: This team, with a high amount of creativity and a high pressure deadline, has the highest potential to be both creative and innovative. They may have limited time and resources but they are highly creative, can pivot if necessary, and when facing an imposing deadline, they figure out how to get it done. This is the best possible team; they are highly creative under pressure and when facing a deadline.

Once I learned how to build, nurture, and lead great teams, what we accomplished was amazing. The crazy thing was, the more I praised individual team members to their face or to my senior partners, the more credit I received. My senior partners would say, “Yeah, but you hired and led that team. We know they are amazing. But it’s your confidence and trust in the team that makes you a great leader. And you get everything done well and on time. Clients love you. Keep it up.” It took me some time early in my career to realize that the potential of my career success would be based on other people accomplishing tasks and projects for which I was accountable. Once I understood this, my career opportunities exploded.

For instance, the team we built for the Amazon account was incredible. The team had to define a new marketplace, conduct the research, understand this new thing called the Internet, create the campaign, and unleash the marketing in less than ninety days, all while working directly with Jeff Bezos (who had no marketing employees at the time) and with his venture capitalists constantly questioning our marketing strategy. What a rush. What a great team. Oh, and I think Amazon did okay.

Invariably, every team faces challenges and problems. And in order to solve those problems or overcome a challenge, they need to collectively understand the real problem and then generate ideas to solve the problem. Almost every team will turn to brainstorming at some point. And so many brainstorming sessions are like “idea contests” with no real structure or framework. In Chapter 7, I will share with you my point of view on brainstorming—that is, why you should only do brainstorming with a “tool” and a defined framework and not as some random group think. Then, in subsequent chapters, I will share some amazing brainstorming tools and a powerful framework.

CREATIVE / INNOVATIVE INSIGHT

The founder of this company had a passion and perhaps an idea, but needed what he did not know he needed: a team. The founder grew up in the New York area; he led a rather normal life, went to college, and then became a DJ. He loved music and hung around with people who loved music and art. Once, he wrote a letter to a very popular DJ duo in Europe asking them how much would they charge to come to New York and play their music. The DJ duo replied that they needed “$15,000 and two first-class plane tickets.” The founder had no money but instinctively knew people in New York would pay to see the DJ duo. But he did not have the resources and so no DJ duo. Still, the experience sparked an idea: What if there was a collective voice, rather than an individual one, that could come together and pool their financial resources? Over the next few years, he noodled and refined the idea but it never went anywhere. Then he met a freelance musician and told him of his idea. For the next two years, both of them pursued “the idea,” drawing and sketching out how it would work. Finally, they met a designer and showed him their drawings. The designer went to work and built a website. They launched the website to help filmmakers and artists get their projects funded from a collective voice. Kickstarter was born.

Key Takeaway

Ideas are great, and while a founder can come up with an idea to start a company, you need a team to build a company. And if the “team” has the mutual passion to be on a mission, then you might create something great.

No employee can work alone for long. You have to work with colleagues to accomplish a task efficiently, with each person bringing his or her particular best to bear on the task. Think Apollo 13. It took the astronauts and NASA’s Mission Control working together to get the spacecraft back to Earth. One person didn’t just turn the ship around.

No employee can work alone for long. You have to work with colleagues to accomplish a task efficiently, with each person bringing his or her particular best to bear on the task. Think Apollo 13. It took the astronauts and NASA’s Mission Control working together to get the spacecraft back to Earth. One person didn’t just turn the ship around.

Which decisions or activities will harm the business significantly if you get them wrong, even when everything else is going right?

Which decisions or activities will harm the business significantly if you get them wrong, even when everything else is going right?