Why is it necessary to solve the problem?

Why is it necessary to solve the problem?The key to understanding a potential problem is learning how to ask the right questions. A great tool for this is the Phoenix List, a list of questions the CIA developed to help with tough or cold cases. It’s useful when looking at a current opportunity where iteration or innovation is needed but you or the team are stumped. Let’s start at the beginning: What is the problem?

Simple and smart questions define problems well and lead to a clear vision of the issues involved. When that occurs, it’s easier to run multiple scenarios to their conclusion and find the best solution to the problem.

Here are four insights that will have you asking better questions:

1. Questions help people discern. Dolphins use sonar to “see” in murky or dark water. They send out a click sound and wait for the echo to return. Once they have enough echo responses, they can navigate, find prey, and avoid obstacles and predators. Questions are the business equivalent of sonar. Asking the right question will help you find your way through a problem, locate the right customers, avoid future difficulties, and outperform your competitors. Questions also act as a filter that will help you decipher the key elements of a problem.

2. Deep assessment is necessary. To reach a solution, finding answers to the “What?” (What is broken . . . is working . . . needs improvement . . . must be changed . . . will have the biggest impact?) and the “Why?” (Why did this happen . . . are our customers considering the competition . . . are we losing this market . . . are we using this process . . . is our product third instead of first?) is critical. Questions such as these matter. Asking a series of clear questions leads to precision. When questions are developed with this result in mind, they will generate a natural sorting and sifting during the discovery process.

3. Frame your questions in layers. Unfortunately, most people don’t take the time to frame the questions beforehand or to ask questions in layers. Effective questions are powerful and thought provoking. They are open ended and not leading. They are more often “What?” or “How?” questions. Although “Why?” questions are good for soliciting information, they can make people defensive—so be thoughtful in your use of them. Also, to be an effective questioner, wait for the answer—don’t provide it yourself.

4. Understand the problem together. When working with other people to solve a problem, it’s not enough to describe the problem to them; they need to understand it for themselves. You can help them do this by asking questions that lead them to think about the topic. A great opener to any new project is: “What do you think is the problem?” Behind effective questioning lies the ability to listen to the answer and suspend judgment. This means being intent on understanding what the person is really saying. What is behind his or her words? Fear? Excitement? Resistance? Let go of your preconceptions so they don’t block you from learning more information. Gather the facts and then pay attention to your gut for additional data.

When you ask smart, simple questions, you will connect with people in a more meaningful way, understand the problem with greater depth, defuse volatile situations, get cooperation, seed your own ideas, and persuade people to work with you because you’ve gained their confidence. Most important, you will be able to work through and discard a series of possible solutions that will lead you to the one best scenario that you’ll implement. Using this method, you’ll increase the likelihood of developing the right answer to the problem—and increase your knowledge base at the same time.

When solving a problem, lots of people are taught to research the problem and analyze the data. But the missing piece is the “thinking” part. And that needs to happen regularly from beginning to end in order to understand the system involved and how the parts work together. That’s why I love the CIA’s Phoenix List.

Research without thinking only takes us to obvious places. We don’t see connections because we don’t look for them; instead, we’re only seeing connections from others’ research and opinions. We’re only seeing what presents itself, which is just data. In the end, we’re left with no insights about the problem we’re solving, but only a catalog of facts that are pretty obvious to both ourselves and everyone else.

The Phoenix List of questions was developed by the CIA to encourage agents to look at a challenge from different angles regardless of any inhibiting contexts, essentially creating multiple thought experiments for us to logically and systematically navigate the problem, giving us a much fuller understanding. And with a fuller understanding of the problem comes more energy spent on highly relevant solutions. When presented with a challenge, knowing what to ask is the difference between doing more of the same and doing something extraordinary.

Using the Phoenix List is like holding your challenge in your hand. You can turn it, look at it from underneath, see it from one view, hold it up to a different position, and imagine solutions.

It’s very easy to get started. Just follow this process:

1. Write your challenge to the problem. Isolate the challenge you’re thinking about and commit yourself to an answer by a certain date.

2. Ask the questions. Use the Phoenix List of questions to dissect the challenge into as many different parts as you can.

3. Record and draw your answers. Don’t be judgmental or critical; record every answer to the questions and draw out problems and answers when you can.

First, you use the “Problem” questions to really identify the problem and possible solutions; then you use the “Plan” questions to help you refine the solution you intend to implement. Here are the questions:

Why is it necessary to solve the problem?

Why is it necessary to solve the problem?

What benefits will you receive by solving the problem?

What benefits will you receive by solving the problem?

What is the unknown?

What is the unknown?

What is it you don’t yet understand?

What is it you don’t yet understand?

What is the information you have?

What is the information you have?

What isn’t the problem?

What isn’t the problem?

Is the information sufficient? Or is it insufficient? Or redundant? Or contradictory?

Is the information sufficient? Or is it insufficient? Or redundant? Or contradictory?

Should you draw a diagram of the problem?

Should you draw a diagram of the problem?

Where are the boundaries of the problem?

Where are the boundaries of the problem?

Can you separate the various parts of the problem? Can you write them down? What are the relationships of the parts of the problem? What are the constants of the problem?

Can you separate the various parts of the problem? Can you write them down? What are the relationships of the parts of the problem? What are the constants of the problem?

Have you seen this problem before?

Have you seen this problem before?

Have you seen this problem in a slightly different form? Do you know a related problem?

Have you seen this problem in a slightly different form? Do you know a related problem?

Can you think of a familiar problem having the same or a similar unknown?

Can you think of a familiar problem having the same or a similar unknown?

Suppose you find a problem related to yours that has already been solved. Can you use it? Can you use its method?

Suppose you find a problem related to yours that has already been solved. Can you use it? Can you use its method?

Can you restate your problem? How many different ways can you restate it? More general? More specific? Can the rules be changed?

Can you restate your problem? How many different ways can you restate it? More general? More specific? Can the rules be changed?

What are the best, worst, and most probable cases you can imagine?

What are the best, worst, and most probable cases you can imagine?

Can you solve the whole problem? Part of the problem?

Can you solve the whole problem? Part of the problem?

What would you like the resolution to be? Can you picture it?

What would you like the resolution to be? Can you picture it?

How much of the unknown can you determine?

How much of the unknown can you determine?

Can you derive something useful from the information you have?

Can you derive something useful from the information you have?

Have you used all the information?

Have you used all the information?

Have you taken into account all essential notions in the problem?

Have you taken into account all essential notions in the problem?

Can you separate the steps in the problem-solving process? Can you determine the correctness of each step?

Can you separate the steps in the problem-solving process? Can you determine the correctness of each step?

What creative-thinking techniques can you use to generate ideas? How many different techniques?

What creative-thinking techniques can you use to generate ideas? How many different techniques?

Can you see the result? How many different kinds of results can you see?

Can you see the result? How many different kinds of results can you see?

How many different ways have you tried to solve the problem?

How many different ways have you tried to solve the problem?

What have others done?

What have others done?

Can you intuit the solution? Can you check the result?

Can you intuit the solution? Can you check the result?

What should be done? How should it be done?

What should be done? How should it be done?

Where should it be done?

Where should it be done?

When should it be done?

When should it be done?

Who should do it?

Who should do it?

What do you need to do at this time?

What do you need to do at this time?

Who will be responsible for what?

Who will be responsible for what?

Can you use this problem to solve some other problem?

Can you use this problem to solve some other problem?

What is the unique set of qualities that makes this problem what it is and unlike any other problem?

What is the unique set of qualities that makes this problem what it is and unlike any other problem?

What milestones can best mark your progress?

What milestones can best mark your progress?

How will you know when you are successful?

How will you know when you are successful?

In my course, we always use a brainstorming tool to solve a problem in almost every class. We always use the same brainstorming structure to solve the problem. Here is an example I gave my students, and I’d like for you to solve the problem alongside them:

“I just came from the Barnes & Noble CEO’s office,” I say. “The CEO wants a solution to the declining revenue facing B&N. Oh, and he does not want to close any stores. You have about forty-five minutes to solve the problem.”

First, the students, in groups of three to four, spend ten to twenty minutes using Phoenix List questions, and perhaps some simple marketplace research, to address and clarify the problem.

Next, they spend ten to fifteen minutes identifying possible solutions, as many as possible.

Then they spend ten minutes narrowing it down to the best solution(s).

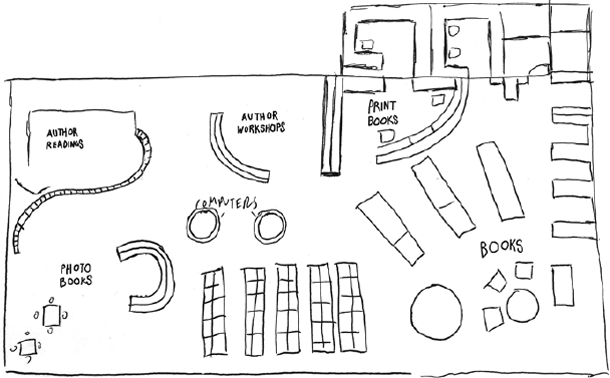

Then they spend ten minutes drawing their best solution, which is then presented in front of the class. With forty-five or so students, that’s about ten to twelve groups, each with their own idea.

Here is the scenario of how you would ask and potentially answer the Phoenix List questions to get at the core problem. The current definition of the problem is declining revenue.

Why is it necessary to solve the problem? If we don’t, the company fails.

Why is it necessary to solve the problem? If we don’t, the company fails.

What is the unknown? The future mix of ebooks versus printed books.

What is the unknown? The future mix of ebooks versus printed books.

Can you derive something useful from the information you have? Self-published and photo book sales are rapidly rising, more than $5 billion combined since 2008.

Can you derive something useful from the information you have? Self-published and photo book sales are rapidly rising, more than $5 billion combined since 2008.

What isn’t the problem? Revenue in the industry is still significant; 2008–2018 revenue will be flat ($15 billion) split between print and ebooks (ebooks rising, print books falling from $15 billion in 2008).

What isn’t the problem? Revenue in the industry is still significant; 2008–2018 revenue will be flat ($15 billion) split between print and ebooks (ebooks rising, print books falling from $15 billion in 2008).

Have you seen this problem before? Yes. Borders bookstores had this same problem; it did not change its business model and it failed.

Have you seen this problem before? Yes. Borders bookstores had this same problem; it did not change its business model and it failed.

Can you restate your problem? Yes. Instead of focusing just on sales revenue, how can we change our business model to acquire more customers?

Can you restate your problem? Yes. Instead of focusing just on sales revenue, how can we change our business model to acquire more customers?

If you keep working your way through the questions, then the plan, you might end up where one of the student teams did in my classroom. In less than one hour, they came up with a potential solution to solve the sales revenue problem and keep 650 B&N stores afloat and growing. They identified what they thought the real problem was and their top recommendations on what to do next:

Real Problem:

The business model for B&N is broken.

Recommendations to Solve the Problem:

Reduce the size of the printed books space in each store by 50 percent.

Reduce the size of the printed books space in each store by 50 percent.

Add a new “self-published” author “store within a store” area for writing workshops and editing and printing services, all generating new revenue.

Add a new “self-published” author “store within a store” area for writing workshops and editing and printing services, all generating new revenue.

Sell local bestsellers through a new local author social media community marketing platform; authors will self-promote their new books.

Sell local bestsellers through a new local author social media community marketing platform; authors will self-promote their new books.

Add a new “create your photo book” area in the store where B&N staff can help customers create their photo books on the spot.

Add a new “create your photo book” area in the store where B&N staff can help customers create their photo books on the spot.

[BARNES & NOBLE REIMAGINED]

Look, I know what you are thinking. A student group on a university campus, even with a creative mindset, a great environment, and an amazing habitat, could not possibly come up with a potential solution to Barnes & Noble’s problem in the marketplace. But they did. In less than one hour. I have been doing brand and integrated marketing for over twenty years and their recommendations are stunningly logical and insightful.

This company, once a fast-rising innovator, had lost its way. Revenue was still growing but its products were becoming “me too” in spite of their high prices. Leadership change was a constant as senior executives came and went. Engineers and product marketing spun out of control and delivered more products to the marketplace to keep the “quarterly” revenue engine running full out. You could almost “feel” the company’s mojo seeping out of its products, employees, and even the buildings. What was the problem? Everyone seemed to have answers but no one seemed to have a strategy or a solution. In desperation, the company’s board brought back one of the founders. Finding the company at the edge of bankruptcy, the founder decided the company would concentrate on just four product lines and declared that “innovation” and “delighting the customer again” was the focus, not revenue or profitability. The very next product was a major hit. Steve Jobs was back at Apple.

Key Takeaway

If you work in a company or are leading one, investigate and understand the difference between a symptom and a problem. It’s critical to question everything until you arrive at the core problem. Then empower people to solve the problem.