In the 1970s, researcher and educator Tony Buzan formally developed the idea behind mind mapping. The map’s colorful, spider- or tree-like shape branches out to show relationships, solve problems creatively, and help you remember what you’ve learned. This chapter walks you through what a mind map is, explains how to construct and use it, showcases the benefits, and gives you an example of a live exercise I use in my Creativity and Innovation course.

It’s hard to randomly generate good ideas unless they are connected to a central thought. That is the power of a mind map. Mind mapping is a visual form of note taking that offers an overview of a problem and its complex information, allowing you to comprehend ideas, create new ones, and build connections. Through the use of colors, images, and words, mind mapping encourages you to begin with a central problem and expand outward to more in-depth subtopics. Eventually, as you branch out, you can begin to identify solutions to the core problem at the outer ends of the branches.

Let’s look at a simple but frustrating problem we all have probably experienced in order to help you better understand the concept of a mind map. The problem: plane flights being late. First, imagine an airplane flying in the sky. When you visualize or see an airplane in the sky, the airplane is your central focus at that moment. But your brain isn’t done there. It also immediately begins to make references, or associations, to the airplane. These associations might include the color of the sky, different types of planes, how they fly, pilots, passengers, airports, and so forth. Because we think in images, not words, these associations often appear in a visual form in our minds. Your mind instantly starts making a map, creating links between these associations or concepts—a mental sort of spiderweb.

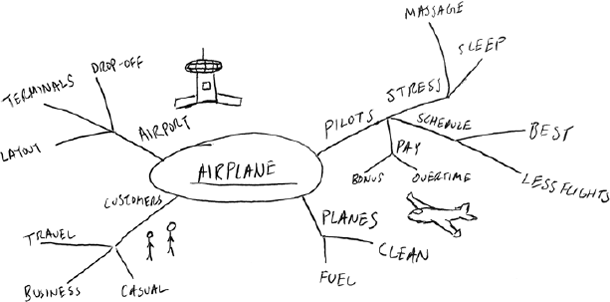

Now, think about planes arriving and taking off late. Why are they late? In order to understand the problem, you have to list all the major associations with the problem using main branches and then subbranches. Visualize a spiderweb or a tree full of branches now. With a mind map, you take the concept of the airplane and write AIRPLANE in the center (the spider’s body or the trunk of the tree) of a horizontally oriented, blank piece of paper. Then, radiating out from the airplane are different- colored “main” lines (tree limbs or spider legs). On these you write the associations you had with airplanes, such as PILOTS and AIRPORT. From each of these are more associations, which you note on individual lines. In association with pilots you might think of their pay or training or even their stress. And so the mind map grows—(see Solving Late Plane Flights). Until you get to the ends of the branches or the web and begin to look at solutions to the problem for that branch.

[SOLVING LATE PLANE FLIGHTS]

For example, with pilots, we can look at scheduling or high levels of stress and begin to suggest possible solutions, such as dynamic scheduling or massage therapy between flights. The great thing about a mind map like this one is that the entire team is creating it all on one page at the same time. So people build on each other’s ideas in a visual way. That spawns other ideas or branches. Which leads to new potential solutions to the problem.

The benefits of using IdeaGen mind mapping are many. While brainstorming teams may not recognize the benefits immediately, once the core problem goes down in the center, then major attributes related to the core problem are identified and the “idea branches” and sketches start to flow. Let’s look at the benefits:

Use your brain the way it thinks. When our brains lock onto something—an idea, sound, image, emotion, etc.—that “something” stands at the center of our thinking. Radiating out from it are countless other ideas, images, emotions, etc., that our brains associate with it. A mind map encourages radiant thinking by manifesting connections between and among these different pieces of information and concepts. And the more connections or associations our brains make to a thing, the more likely we are to remember it and use it.

Create and communicate information rapidly. Making these connections allows you to create and communicate information rapidly. As Randy L. Buckner and his associates noted in their 2008 Harvard University study, “The Brain’s Default Network,” writing and imagery both improve memory, creativity, and cognitive processing, and color is also a potent memory enhancer.

Map your way to “seeing” the problem. As humans we constantly create and devise approaches for solving problems. Doing so requires brainstorming. For instance, whether your concern is your wedding, new recipes, an advertising campaign, proposing a raise to your boss, better managing your money, a health diagnosis, or an interpersonal conflict, all can be mind-mapped. Mind maps are tools to capture information that’s directly relevant to a problem, so you can compress large amounts of information quickly and easily.

Easily consume information and then use it. A mind map can order a complex process or system such as stock trades, computer networks, or engine mechanics.

Easily picture solutions. Finally, mind maps are useful in planning and executing potential solutions to problems. Adding small images and drawing out other iconic representations drive even more creativity. It is also a great visual tool for communicating the actual problem and potential solutions.

Let me walk you through another example of an exercise I use in my classroom so that you better understand the structure of using mind mapping in a brainstorming meeting. Imagine you are a student in my classroom and this is what happened when I walked into class one day:

“Our company has grown rapidly and we are now over 500 employees,” I said. “But HR has noticed people are starting to miss work due to sick days. What is the problem and potential solution? You have forty minutes to come up with some solutions to the problem.”

First, the students, in groups of three or four, spent five to ten minutes agreeing on the core of the problem; in this instance they determined the core problem of the employees to be their overall “health.”

Next, they spent ten to fifteen minutes brainstorming using a mind map. They drew the core branches and then as many subbranches as possible, roughly sketching ideas and throwing down words on a poster-size piece of paper.

Then they spent ten minutes coming up with solutions to problems at the end of their branches.

Then they spent ten minutes refining their mind map, which was then presented in front of the class.

This is the best map they created around the core problem of “health”:

[HEALTH SOLUTIONS VIA IDEAGEN]

Core branches of sleep and rest, food, sanitation, medical, and exercise

Core branches of sleep and rest, food, sanitation, medical, and exercise

Subbranches relating to main branches that further defined the problem

Subbranches relating to main branches that further defined the problem

Potential solutions such as nap time at work, an on-site nurse, daily exercise breaks, and balanced and healthy cafeteria options

Potential solutions such as nap time at work, an on-site nurse, daily exercise breaks, and balanced and healthy cafeteria options

You can see by the mind map that the core problem the students identified was not “too many sick days.” Instead, they saw a high number of sick days as a symptom of other potential problems. You can see why proper identification and agreement of the problem is critical.

CREATIVE / INNOVATIVE INSIGHT

This entrepreneur started life in Europe and moved around several times before settling in London. He started playing with programming code and was fascinated with several application platforms, including social media and smartphones. He was curious about how and why people did what they do on these platforms and what kind of problems they encountered. He built several applications and tested them. Some gave him insight; others tried to solve a problem. He watched what people did when using their applications—and what they “consumed.” He noticed a problem. He designed an application to solve the problem. He got a lot of downloads. A venture investor contacted him and offered an investment to take the application to another level. He took the money and pulled together an amazing team, including a scientist and several developers. Two years later, Yahoo! bought the company for $30 million. The entrepreneur was Nick D’Aloisio, who was just seventeen years old.

Key Takeaway

Be curious about what people “consume,” no matter the product or service. Look for problems. Above all, if you get the chance to build a great team, build one that scares you personally. You don’t have to be the smartest person on the team; just be the best leader.