On the first day after winter break, at recess, Denise met me in the staircase. We still didn’t know what was behind the door at the top of the stairs, but by that point I’d given up on even checking the lock. I didn’t even go all the way up anymore and had taken to sitting at the bottom of the stairs, to be closer to where Denise would be.

I asked her how her Christmas went, what gifts she’d gotten, but she said she didn’t want to talk about it, as if something horrible had happened, except I was pretty sure nothing horrible had happened to Denise over Christmas break other than being at home with her parents—whom she thought were stupid, who maybe were (she complained they often wore matching T-shirts stating their star signs)—and being forced to eat more than she wanted.

“Isn’t there one thing you like about Christmas?” I asked her. “One food?”

“As far as meals go, I only tolerate breakfast,” Denise said, which would’ve been understandable if she’d been talking about a real breakfast with lots of bread and butter, but I knew she meant fruit and eggs. I knew that was all Denise ate, and that she would only eat it in the mornings, sometimes for lunch if she really had to, but she didn’t understand dinner. Dinner was for her the most useless thing because she said we didn’t need energy before bed. I didn’t know how anyone could elect not to have dinner. I sometimes thought dinner had in fact only been invented to give people a reason to go through the day.

“I don’t know what I would do with myself at night if dinner didn’t exist,” I said.

“That’s because you’ve been raised with dinner as a convention. And you’re a conformist. All children are.”

I took this as an insult but then I realized taking the word conformist as an insult was the most conformist reaction and so I let it slide.

“Did you watch the New Year’s TV movie this year? On Channel One?” Denise asked.

I said we never watched French TV movies in my family. “My brothers and sisters are strongly anti—”

“Right,” Denise said. “I forgot you came from people of taste.” She wasn’t being sarcastic. She didn’t know anyone in my family but for some reason assumed we formed a perfect inverted model of hers, of which she was the only child and the only intelligent member (I wondered if that made me, to her mind, the only dumb member of mine).

“We watch stupid American shows all the time,” I said, to make my family sound more normal.

“Anyway, my parents obviously make me watch the Christmas special every year, and it was really bad once again, but guess what?”

I couldn’t possibly have guessed what Denise would say next.

“Do you remember those videos they showed us in fourth grade?” she asked, knowing I would. “With the kids who’d never seen the ocean?”

“Of course I remember,” I said, a little too enthusiastically. “I didn’t think anyone had paid attention to those videos but me.”

“You did put a lot of money in Miss Faux’s jar back then,” Denise noted.

“You saw me?”

“Everyone saw you. You must’ve dropped like thirty coins in there. Slid them in the slot one at a time, all solemn, like you were saying a little prayer after each coin drop.”

“I wasn’t,” I said.

“You really wanted those kids to see the ocean, I guess.”

Denise was making fun of me. Her mood that day indicated school had just started again. She was always slightly less depressed after school breaks, because she felt she’d broken free from the “parental yoke” and experienced a rare sense of lightness, “like when you bike downhill after a tremendous effort going up,” she’d once explained. The feeling usually subsided by the third or fourth day back.

“Well guess what?” Denise repeated, serious again. “One of the actresses in the Christmas special, the star of it, actually, I swear to God, she was in that video. She was one of the ‘poor kids’ seeing the sea for the first time.”

“Which one?” I asked. “Juliette?”

“Juliette,” Denise confirmed.

She didn’t look surprised that I would remember not only the faces but the names of the kids in the charity video, but I still felt I had to justify it.

“Juliette is actually the only one I remember,” I said. “I had a little crush on her.”

“Me too,” Denise said, and it caught me so off guard that I pretended both our confessions had overlapped and I hadn’t heard hers.

“So she’s famous?” I said. “That’s nice. I bet she’s able to see the ocean whenever she wants to now.”

“You’re not following me,” Denise said. “I think Juliette was never a poor kid who hadn’t seen the ocean. I mean, I guess at some point early on in life, she was, unless she was born on the beach like those turtles or something, but anyway, my point is: I think those videos were entirely scripted. I think the kids in the videos were all fake. All actors.”

“I don’t buy it,” I said.

“You should look her up online. Juliette Corso. You’ll see.”

I went up the stairs to check the door. It was locked.

“It says she was already an actress four years ago?” I asked, and Denise said yes, that she’d spent a while doing research on Juliette these past few days.

“Maybe both things are true,” I said, coming back down the stairs. “Maybe she was a child actor and had never seen the sea, and the charity helped her and her little brother.”

“I guess it’s possible,” Denise said.

I’d often wondered what had happened to the kids in the Let Them Sea video. Despite my donation, I was ambivalent about their work, the work of one-time charities in general, as opposed to the charities that helped people, the same people, over and over, for as long as they needed it. Of course, the one-time charities left you with a memory to cherish, you got to have something for a little while, but then you had to pass it on for the next guy to enjoy, and I couldn’t tell whether it was easier to live without something you’d never experienced or experience it once and go back to living without it. I hoped for the kids in the videos that they’d gotten to see the sea again and again, not just that one time. I realized I hadn’t seen the sea myself since the father had died. It made sense that the father’s being dead meant we would never take a road trip again. My mother hated driving.

“So you like girls?” I asked, because I wanted to think about something else.

“I don’t like anybody,” Denise said.

I decided it was time to focus on school and getting smarter. My German had reached a plateau that year. Herr Coffin was less encouraging than he’d been, even though I was still among his best students. One day after class I decided to speak to him directly, ask him if he thought I had what it took to be a German teacher. I’d never talked to any of my teachers one-on-one before, the way my siblings had done since kindergarten. I believed only great students were allowed to stay in the classroom after the bell to chat with teachers while they packed their satchels. I believed details about the day’s lesson were discussed, points of view exchanged, extra reading suggested. But then in junior high I’d started seeing kids even dumber than me linger around after French or math hours. Did they think they were smarter than they were? Why did teachers allow their five-minute break between classes to be wasted on mediocre students? What did they have to say anyway? I’d asked Simone what she thought about this and she’d said that “regular kids” were only interested in talking about themselves, so she assumed the only reason they went to a teacher after hours was to seek advice about their future in a way they believed to be humble but was in fact a conspicuous play for attention, a way to verify they’d been noticed in spite of their lack of academic promise. “Even worse than that,” Simone had said, “they talk to a teacher in the hope that the teacher’s detected something unique about them. They know they suck, but they’ve been told everyone has a purpose in life, so they want to find out what theirs is. They think teachers have the means to decode the particular ways in which a student sucks and make them correspond to a career path the student should engage in. They think their sucking at something automatically indicates they’ll be good at another thing.”

I didn’t think I fell into the category of students Simone had described. I didn’t suck at German, and I was planning to go to Herr Coffin with a reasonable question, not for a pat on the back. I wanted his honest opinion. As I walked toward his desk, though, after everyone else had left the classroom, I became nervous about what Herr Coffin would say. What if I didn’t have what it took to be a German teacher? What else was I remotely good at?

“Herr Coffin,” I started, and I stopped awkwardly right there because I didn’t know if I should address him in German. He spoke French and allowed it in class now sometimes, when we did translation from German texts into our native language, but still. I would make a better impression, given the question I wanted to ask him, if I put it in German. Or would it just sound like I was trying too hard? As far as I knew, no one had ever stayed beyond the bell to talk to him. There was no precedent for me to refer to. I tried German.

“Herr Coffin,” I started again. “Denken Sie, dass ich einen guten Deutschlehrer werden könnte?”

Herr Coffin looked over his glasses at me.

“Is that what you aspire to?” he replied, not in German. He seemed to be trying to make sure I wasn’t pranking him. “Are there any other lines of work you’re considering?”

“Just German so far,” I said.

Herr Coffin looked down at his satchel like I’d just delivered very sad news.

“When did you know you wanted to be a German teacher?” I asked him.

“Me?” Herr Coffin said after realizing there wasn’t a third person in the room, genuinely surprised, it seemed, to be asked a personal question. “I never wanted to teach,” he said. “The vocation of teaching is a rare and precious thing. In thirty-seven years of teaching, I have only met a handful of passionate professors.” He paused there, as if to pay them a silent tribute. “The majority of my colleagues, though, are only passionate about the German language, the way I was. The way I am,” he said, correcting himself immediately.

“So, what is it you wanted to do?” I asked.

“I love German. I wanted to know everything about German, every subtlety, every possible double entendre. I wanted to read Schlegel all day,” he said, assuming I knew what he was talking about, “his own writings as well as his translations of Cervantes, and Shakespeare, and understand why he translated a certain thing a certain way and not another, figure out when it was that the sounds a German sentence made became more important than a word-for-word translation—”

“So you wanted to be a translator?” I said.

“No, not exactly. I just wanted to study, to keep studying. But it is a mistake to think that teaching a discipline is another way to keep learning about it.”

Talking to Herr Coffin was starting to feel like talking to a sister.

“I’m not a good teacher,” he added.

“I think you’re great,” I said.

The silence that sat between us at that point was made even more awkward when we heard one of my classmates, out in the hallway, distinctly call another a “fissured anus.” Herr Coffin played deaf and went back to his satchel.

“I don’t think I am really passionate about German,” I admitted.

“Good,” Herr Coffin said. “Then maybe you’ll like teaching it.”

The only practical advice I got out of Herr Coffin as I inquired about ways to improve my German was that I should look for “conversation partners,” people who were fluent and would help me catch the rhythms of daily German and bask in its melodies.

“School makes you believe one needs years and years of classes to learn a language when what it really takes is a few months’ immersion,” Herr Coffin had said. “Immersion will forge an internal compass inside your brain,” he’d added, moving his index finger left and right in the air to illustrate compass in a way that looked a lot more like metronome. “When the time comes for you to craft a sentence in German, the compass will tell you immediately if you’re heading in the right direction.” Herr Coffin hadn’t offered to be my conversation partner, though, and now that the father was dead I didn’t know anyone who spoke German, so I decided to place an ad on the Internet.

It seemed, however, that all websites that put you in touch with other people were dating platforms. Even those that advertised their goal as “building a stronger community” had pictures of romantic sunsets or older couples holding hands. Some were very specialized, targeted at businessmen and young women who never wanted to work, for instance, or at widows and widowers. At Calvinists, even. I thought maybe the proportion of Calvinists who spoke German would be greater than that of the general population, but the Calvinist website was for dating only, and I didn’t want to date a Calvinist. Not that I had anything against Calvinists, but I’d been told they were serious people, and I didn’t want anything serious. I wanted to focus on my studies.

I picked the website with the sunset. I had to create a profile first if I wanted to see anyone else’s. While I was at it, I thought it would be a good idea to look for “conversation partners” for Aurore as well (she still couldn’t drag herself out of the house). And for my mother too, maybe. By “conversation partners,” I meant boyfriends of course. I set up a profile vague enough that it could work for all of us.

GENDER: n/a

SEEKS: men/women, friendship/casual/lifetime partner/love/conversation

AGE: undisclosed

FIELD OF WORK: other

CARE TO SPECIFY?: humanities

HOBBIES: indoor activities

SMOKING: occasional

DRINKING: occasional

SAY A FEW WORDS ABOUT YOURSELF [200 MAX.]: Hello! Guten Tag! Looking for bilingual friends (German, French) for conversations, and a boyfriend between ages 25 and 60. I would like to meet you if you like talking about life and books, if you speak German, or if you just want to have a good time. I have a yard and a big house. I have no pets but they are welcome if you have them. Looking forward to hearing from you!

Once our profile was set, I started browsing through the people listed in our zip code. Only one person had mentioned speaking German in his profile, and it was Herr Coffin. Herr Coffin was seeking a life partner to have glasses of wine and take strolls with along the river on the weekends. I tried to picture him as a stepfather. I broadened the search to include the five zip codes adjacent to ours—there was a button just for that. While I reviewed the profile of a potential candidate for Aurore, I got my first alert. A red heart-shaped icon with a white envelope drawn inside it started beating in the right corner of the screen. I clicked on it. It was from Alex79#69, the first person I’d added to my favorites (you had to click a thunderbolt icon under the description someone had written of him- or herself if you liked it). “Hi,” the message said. That was it. I said hi back and Alex79#69 responded, “are you a boy or a girl? yr prfile is confusing.”

“Girl,” I said, with Aurore in mind—Alex was a twenty-eight-year-old man, too young for my mother. “24 years old. PhD in history.”

“Wow,” Alex79#69 said, and then he didn’t say anything more.

OscarOscar showed more interest when I told him about Aurore’s academic achievements in first person, but then out of nowhere sent this: “would kill mother 4bj rite now.”

“do you speak german?” I asked OscarOscar, just to make sure I wasn’t letting an opportunity go, though I guessed if he’d been of German descent, he would’ve called himself OskarOskar.

“if u blow me good, i speak all language u want,” he responded.

I decided to call it a day on the conversation partner hunt and looked up pictures of Juliette Corso, the destitute/child actor girl from the charity video, instead. Juliette had her own website but the Let Them Sea campaign was not listed among her “works.” It was a pretty short list, actually, a couple TV movies, one commercial for a soda I had never heard of (the commercial had only aired in Belgium), and the movie Denise had seen her in over Christmas break. Her bio said she was from Clermont-Ferrand but had moved to Paris the year before to pursue her acting career. There was mention of her having a dog but nothing about a little brother.

Simone watched me struggle over math homework one evening and reminisced out loud about how easy life had been when she was in my grade.

“I thought every grade was easy for you,” I said.

“I’m not talking about the work,” Simone said, “but about the decisions that had to be made behind the work.”

“What decisions?” I asked.

“Exactly,” Simone said. “My point exactly. You’re in eighth grade: you have no decision to make. You can just do the homework and not question whether you like it or not.”

“I know I don’t like it,” I said.

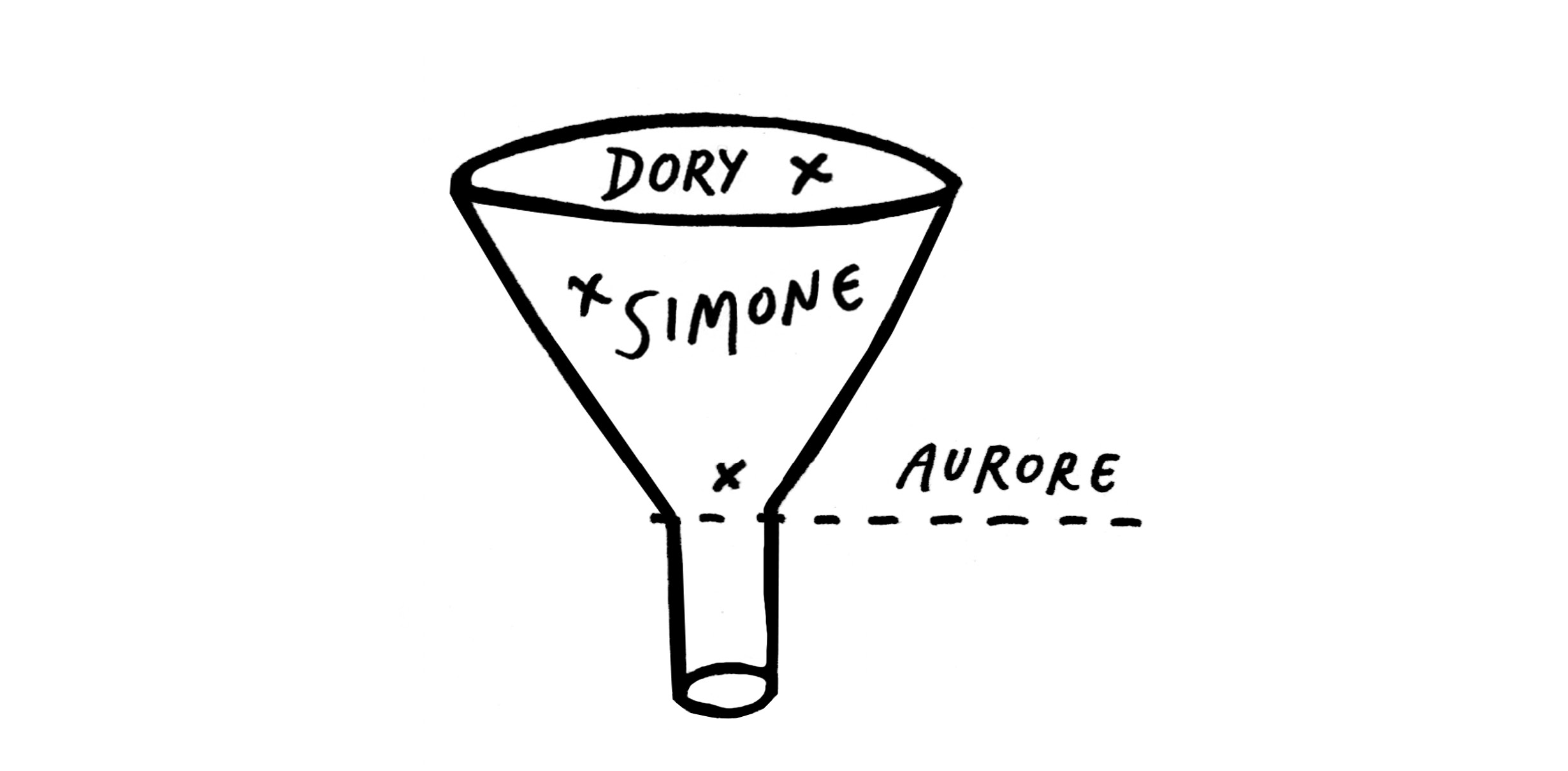

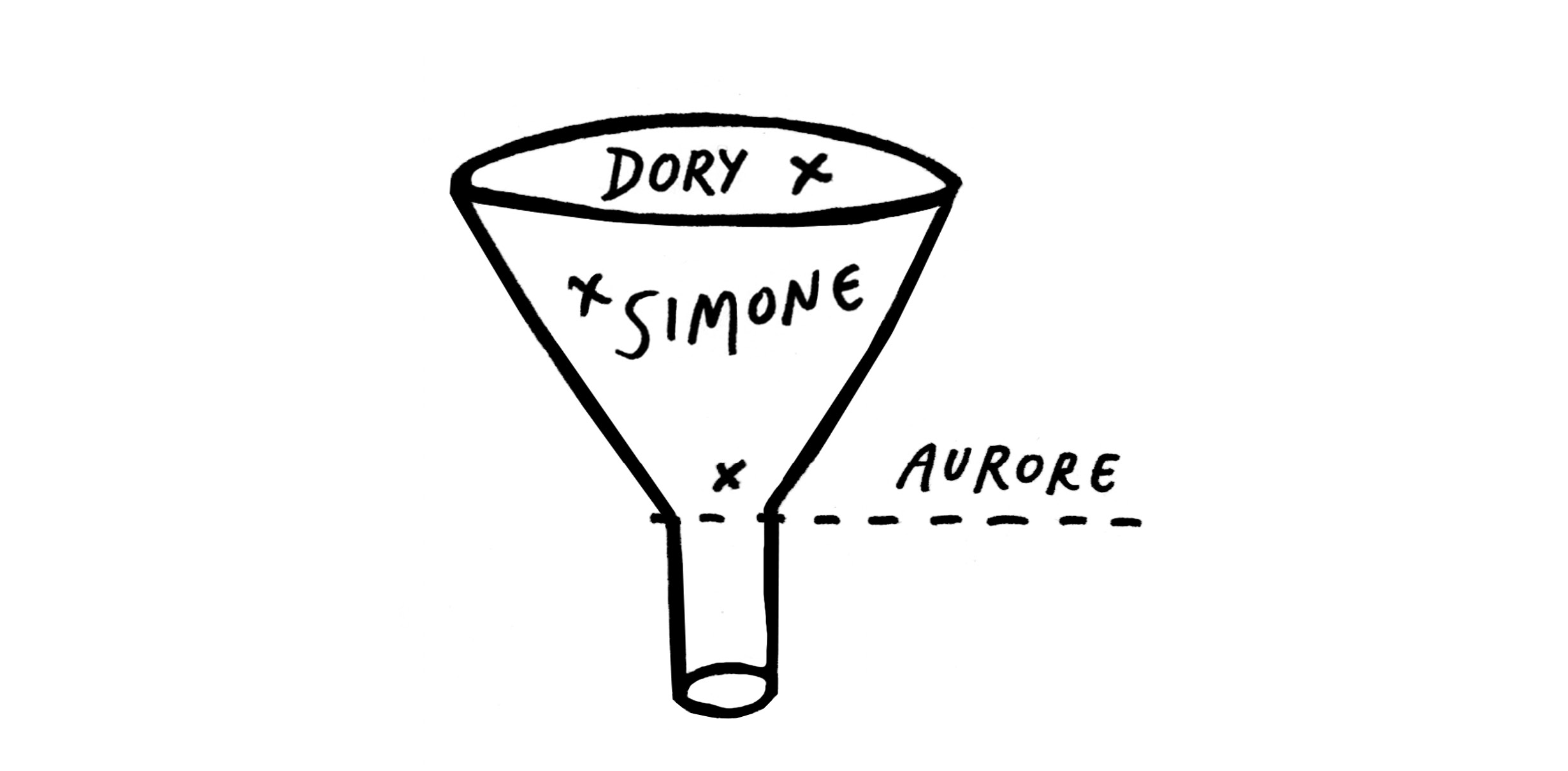

I thought our conversation would end right there but Simone had an image she wanted to share with me.

“We’re all in this funnel, see?” she said, and she grabbed my notebook and drew a funnel on a new page. “Here you are,” she said, drawing an X at the top of the funnel and naming it Dory.

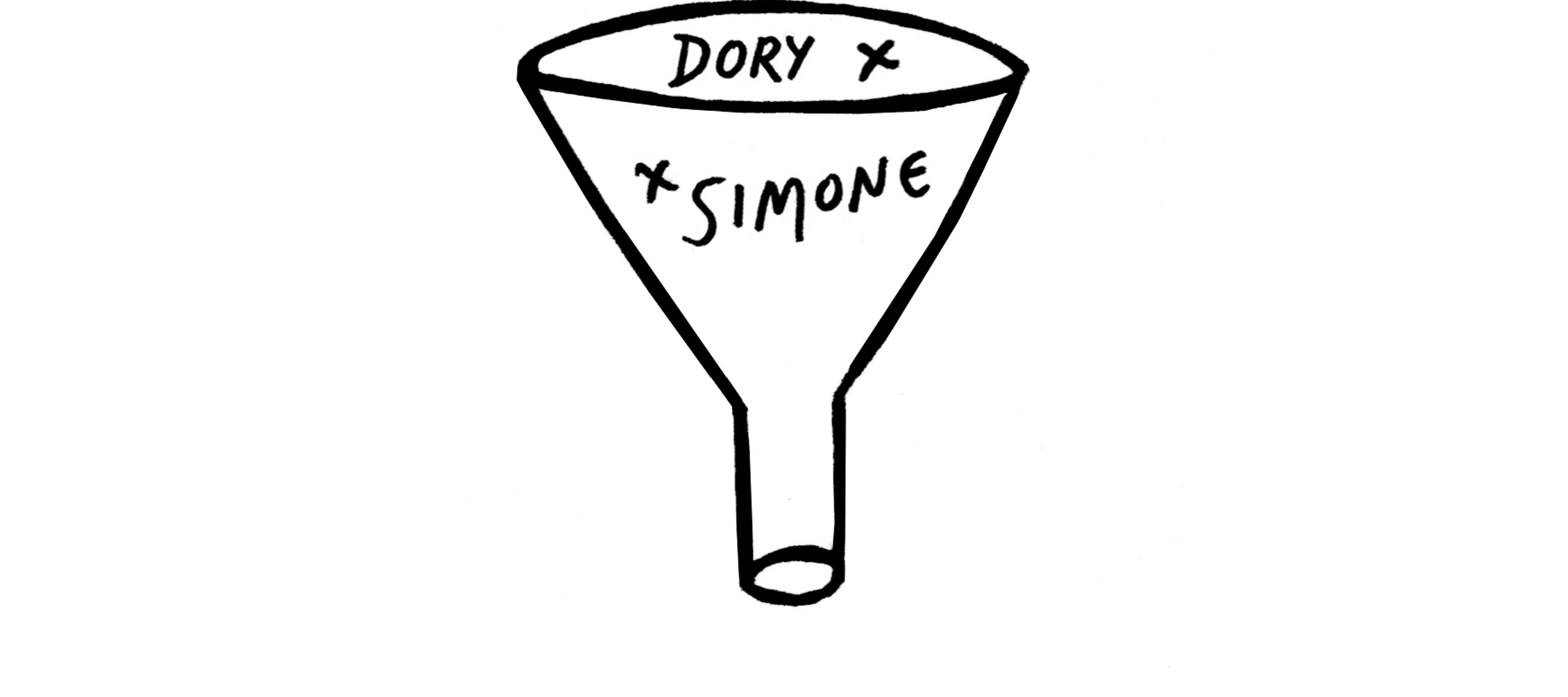

“Here I am.” She drew another X a little lower down the funnel.

“What does the funnel represent?” I asked. “School?”

“The funnel represents our lives,” Simone said. “The possibilities, the choices.” She put her pen to where I was on the drawing. “When you’re born, you virtually have an infinity of options, you get to swim at the top of the funnel and check them all out, you don’t think about the future, or not in terms of a tightening noose, at least.” She pointed at the bottom of the funnel. Then back at the top again, at the X that represented me. “You think, if anything, that the future will be even more of that, get you more freedom, more choices, because you see your parents pushing your bedtime farther and farther and you think, Well that’s swell, you think it means being an adult will just be super, but then little by little, you get sucked to the bottom. You don’t realize it at first. It starts with the optional classes you elect in high school. More literature or more physics? Should you start learning a third foreign language or get serious about music? And then choices you could’ve made for the future get ruled out without you knowing it, and you sink down to the bottom faster and faster, in a whirlwind of hasty decisions, until you write a PhD on something so specific you are one of twenty-five people who will ever understand or care about it.”

“PhDs are not the only option,” I said.

“But they’re the slowest possible way down the drain,” Simone said. “They buy you time, they allow you to believe for a while that the amount of specialization of your thesis verges on some kind of universality—and for the best academics, it does, or at least I want to think so—but then in the end it doesn’t matter how brilliant you are, or that you think you can apply that brilliance to other areas of research: academia has already confined you to the one field you picked years before. That’s why Aurore is all depressed. Aurore is reluctant to go there.” Simone pointed at the neck of the funnel and made an X for Aurore right at the threshold.

“Isn’t everybody?” I said.

“Don’t be so sure, Dory. Some people enjoy being trapped. Some people need it.”

The sound of her own words, or the thought of what she was about to say next, made Simone declare we were on to something and she requested that I start recording our exchange for her biography.

“I was working,” I said.

“Let me repeat myself: what you do in eighth grade is of zero consequence.”

“That’s not what you used to say when you were in eighth grade.”

“Well, I know better now. Trust me. That’s the whole point of having a big sister.”

I took the Dictaphone out of my desk drawer and pressed the REC button without even checking whether I wasn’t erasing a previous interview. I didn’t think I would really write Simone’s biography, and the little part of me that thought I actually might also suspected that when the time came, my memory would be of more help than Simone’s half-true recollections and funnel theories anyway. She cleared her throat.

“I think my biography should start with me gazing through the car window on our way back from summer vacation,” she said.

“When you were practicing melancholy?”

“Right.”

“I never really understood what you meant by that.”

“Practicing melancholy meant looking at everything lying in front of me as if it were already belonging to a distant past.”

“Okay.”

“And making up stories in my head of highly unlikely futures. Trying to remove myself from the present at all costs. It’s like the opposite of meditation, in a way.”

“Why did you do that?”

“I still do it.”

“Why?”

“As an exercise. To boost my imagination.”

“You can’t work on your imagination if you’re in the present?”

“Well, to some extent, sure, you can. But you don’t have that much control over the present—say, the weather, or what other people around you will do. You mostly go through the motions, you know? The possibilities are limited. There’s too little room for analysis and most important, too little room for improvement, which is the key to all art.”

“Do you have to imagine sad things to work on your melancholy?”

“Not necessarily.”

“Why do you call it practicing melancholy then?”

“Because what goes on in your head when you step out of the present is always richer and more satisfying than what you come back to when you’re done. That’s the sad part. That’s what’s at the core of melancholy, not the things you actually imagine. The present is disappointing in a way that you can’t act upon while it’s happening. But once you’ve made a memory of something, you can throw away the meaningless parts and write better versions of it.”

“Like Don Quixote?”

“Well I don’t have that kind of imagination,” Simone said sadly. “But sure. Yes. Don Quixote doesn’t imagine sad stuff most of the time. When he thinks he’s being knighted by the innkeeper, for example, that’s not sad.”

“I haven’t actually read it,” I said.

“Anyway. Most people find it sad that someone would think the present so mediocre that they’d be eager to retreat to a life that is only a figment of their imagination, which is what melancholics do. That’s why they, like you, equate melancholy with sadness, but they’re wrong. Practicing melancholy and being sad are two very different things.” She paused there, before adding: “Also, being in the present sucks because there’s always something sort of annoying going on in your body, whereas if you think in another time dimension, the body becomes less of a problem.”

“What goes on in your body that annoys you?”

“Don’t get me started.”

“What does all of this have to do with the funnel?”

“Everything has to do with the funnel, Dory. We all have to go through the funnel and abandon things on the way down, and I want to be careful about what I leave behind. Lately I noticed I don’t devote quite as much time to my imaginary conversations as I used to. It made me realize I’d gone farther down the funnel than I thought.”

“Is that what you were crafting in your head on the car trips back home? Imaginary conversations?”

“No. The car trips were for imagining implausible futures. Or whole life stories for the people in the other cars. I had the imaginary conversations to fall asleep. I used to have a dozen of them going, and every night, depending on my mood, I’d pick one, rehearse it, polish it…that was the best way to fall asleep. I miss that.”

“Why don’t you do it as much as you used to?”

“I don’t even know. That’s my whole point. The funnel takes things away from you before you know it.”

“Who were your imaginary conversations with?”

“That’s a pretty private question.”

“Don’t you think the readers of your biography will want to know?”

“Well. There were quite a few different types of people. Real people, I mean, people that I knew, famous people, people I made up entirely…Some conversations were aspirational and some pure fantasy. Some I just worked on for a few days—they had to do with world events, you know, like, when they planned new reforms on the education system a couple years ago? I imagined a whole debate with the president on this. I knew the chances I would meet the president on my way to school the next day were pretty slim, but still, I imagined I would, and wrote a whole argument in my head, to be prepared when I did. A pretty powerful argument, as I recall. Some conversations were more plausible, like, when I had a frustrating teacher? A teacher I was smarter than but who pretended not to notice? Well, I imagined a whole conversation where I crushed him in front of the whole class. It was very satisfying. In my head, I had a conversation with Mr. Mohrt every single night of ninth grade, or close to it. I spent so much time on that one I’ll probably remember it on my deathbed. Just talking about it now I have whole portions rushing back to my head.”

“What about the people you made up? Were they like imaginary friends?”

“No, of course not. That would be sad.”

“Who were they then?”

“Interviewers, mostly.”

“Many?”

“Just two different ones. I mean, I didn’t invent much about them to be honest, they were basically faceless, we didn’t have conversations per se, they were just there to interview me. I’d pick one or the other, again, depending on my mood. One of them was just there to make me look good, ask the questions for which I had cool and smart answers. And the other one was more of an opponent, you know? I could just lash out at him and verbalize everything I thought was wrong about the world. They were both a great way to work some of my thoughts out.”

“What kind of interviewer am I?”

“You don’t challenge me much.”

“So I’m the first kind. I’m here to make you look good.”

“Both my fake interviewers made me look good. Those are imaginary conversations I’m talking about. I’m always going to have better arguments than the other guy.”

“Always?”

“Yes, I don’t think there really is a way around that. I tried not to make it too obvious for a while, to leave the other one a chance to say something as smart as me, but it’s hard to be a hundred percent fair in an imaginary conversation, you know? It’s like when you play both parts in a chess game because you can’t find a partner.”

“I know exactly what you mean,” I joked. Simone didn’t get it was a joke.

“Right? You’d think because it’s your brain playing both sides, it’s going to be hard picking which side you’d rather see winning, but then as the game goes on, you develop a fondness for the way you’ve been playing on one side of the board rather than the other. And I mean, of course you’re always going to win the argument or have the best lines in your imaginary conversations. What would be the point otherwise? You’re creating them for yourself, for your own personal use, so they should empower you a little. That’s why people have them.”

“You think everyone has them?”

“They have to. With their bosses, wives, everyone. Fictional characters.”

“Dead people?” I asked.

“I don’t know about that,” Simone said. “I tried once. I think there’s not as much satisfaction in it if there is no hope at all that you’ll get to actually have the conversation with the person at some point.”

“What dead people did you try with?”

I thought she would say the father but she said, “Romain Gary.”

The only imaginary conversations I’d had had been reenactments of real ones gone bad, like the one I’d had with Sara Catalano at Daphné Marlotte’s 111th birthday party when she’d called me a perv. I never invented from scratch. What I did sometimes to fall asleep, instead of inventing conversations with actual people, was to make up extra dialogues in the movies I loved. I often imagined having a part in them. But it was hard to write myself in and keep the movies good, so I tried to have a secondary role, minor but efficient, to not alter too much of the plot. I would only be there to change a small little thing that would make the main characters happier. Like, in Return of the Jedi, for example, I was a rebel who’d been made prisoner on the Death Star, and I’d managed to escape from my cell during the panic ensuing from the first rebel-fighter hits on the station. On my way out, I saw Luke dragging dying Vader to safety, and I helped him out with that. Instead of leaving Luke and his estranged father to have a rushed last exchange on the deck of the imperial shuttle, I managed to hurry them on board and save Vader while Luke flew us away from the Death Star. After we landed on Endor, I let them both have the space and time they needed to really make peace—they had a lot to talk about, and it seemed that the few seconds Luke and Vader had been given in the real version of Return of the Jedi didn’t nearly cover everything. While they caught up, I just rested and lay on the grass and looked at the stars, and then when they were done, Luke took Vader and me to the Ewok party, and introduced me to Han and Leia, and then since Leia needed her own time to process the Vader situation, I meanwhile tried to make friends with Han. Han sort of sized me up; he felt a bit threatened (I looked good in the movie), but then I made a few jokes, told him my story, and proved myself to be a nice guy who was just happy to chill after everything he’d been through, and who, if Han wanted, could become a lifelong friend and would never put any moves on his lady. THE END. I say “THE END,” but it was in fact never the end. I got caught up in my dialogue with Han Solo sometimes, and started to write a whole backstory for my character, added him to scenes in the previous two episodes, making room for him to potentially appear in the next ones if there ever were any. Maybe it was as Simone said when she talked about her imaginary conversations and how it was impossible not to keep the best lines for yourself: I guess it was hard, even with my intention to not ruin the shape of the movie, to be such a minor character. But what if my presence in the movies I rewrote in my head made the movies bad? Of course I’d be the only one to know, yet I still felt guilty reshaping perfectly good movies by joining the cast, so I started imagining that the movies could all exist as they were, with all the twists and action the audience needed, while I ran a parallel world where little things could always be adjusted and the characters I loved would come for a while and rest, away from the drama and the tears. It had always seemed unfair to me, the amount of complications and bad luck that writers stuck my favorite characters with. And I understood it had to do with Aristotle’s rules of fiction etc., but still. If I’d cheered and felt sad for a character, he automatically had a place in my parallel world of movies where nothing traumatic ever happened.

That winter, Denise finally lost someone. She couldn’t wait to tell me. Because it was her grandmother who’d died and not someone young, she said it was not such a big deal and fell “within the natural order of things,” but still, she’d been fond of the old lady and was going to put all she had into her eulogy.

“You should come,” she told me. “The funeral is Thursday.”

“I can’t skip school,” I said.

“You skip it all the time to run away to Paris or whatever,” she said, and she was right. I just happened to not be as interested in attending funerals as she was.

“I’ll see what I can do.”

We were at the school cafeteria. Denise had taken up the habit of joining me there, even though she never ate anything. She said she only ate in the mornings, but I think some days she skipped breakfast too.

“You should eat a little before gym class,” I said. I knew her schedule. “Have a bite of my rice.”

“Why would I do that?” Denise said. “I’m fat enough as is.”

“You’re the skinniest person I have ever met.”

“Well, I know I’m not fat relative to the others,” she said. “But I’m still fatter than I’m comfortable with.”

“Don’t you want to have tits and stuff?”

“Am I your girlfriend now? What do you care if I have tits?”

“I’ll come to your grandmother’s funeral if you eat some of my rice,” I said.

“My parents tried blackmail,” Denise said. “Doesn’t work.”

I knew I wasn’t putting enough heart into convincing her. My mind was elsewhere. It seems to me sometimes, when I look back on it, that all I wanted to do in eighth grade, whenever I sat anywhere, was to readjust my boxer shorts, and I couldn’t bring myself to do it casually, the way other boys did, reaching down there unapologetically for quick positional fixes and scratches. Since my conversation with Aurore, I’d been constantly checking my penis for bumps and depressions, but it didn’t seem like Rose had given me any of the sex diseases I’d read about on the Internet. I didn’t really know when I could stop looking for signs and consider myself out of the woods, though. It had been four months.

“Tits…,” Denise said. “What would I do with tits anyway? I get why some girls want them. I mean, Sara and Stephanie, they carry theirs well, you know? It’s not disgusting or anything. But me? What am I supposed to do with tits? Lean against the lockers and wait for a boy to notice them? I don’t think so. No. Doesn’t suit my personality. Tits are not for everybody.”

“My sister says personality is a myth,” I said.

“Which one?”

“All of them,” I said. “All fake.”

“No, I meant, which sister?”

“Oh. Simone,” I said.

Denise only knew my sisters from a distance, of course, like most people, but unlike most people, she had no trouble keeping track of which sister thought or had said what, while even teachers who’d had them all in their classes one after the other talked about them like a three-headed entity, sometimes asking me in a hallway to congratulate Aurore for an article Berenice had written, or telling my whole class how my sister Aurore Mazal had once shared with her own grade incredible mnemonics for the Napoleonic wars (mnemonics that encompassed chronology, outcomes, and even some coalition details all at once) while I knew it was Simone who’d come up with them.

“Did Simone start applying to schools yet?” Denise asked.

I said she had, but only to the best preparatory courses in Paris. Simone still couldn’t tell what she would be famous for, so she’d decided the best thing to do while she figured it out should be the most impressive. The school that impressed her most was the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, but to even try to get in there, you had to go for two years in what was called a preparatory class, whose workload ranked as one of the highest in the world (or at least that’s what the Wikipedia page said). Then you could give the admission exam a shot (it was one of the most competitive exams in the academic world as well). All that to study some more. Simone kept talking about how it was the most prestigious school in the world for humanities, but when people (the butcher, neighbors) asked me what was new with my family and I told them about Simone’s latest ambition, they never seemed to know what the École Normale Supérieure was, and it made me sad that Simone was so delusional about the school’s fame. When I’d told her about the École Normale Supérieure, Denise had said she knew exactly what it was, but I’m pretty sure she’d lied, because she hadn’t expanded any on the subject until recess the next day, when she’d proceeded to list for me all the famous intellectuals who’d studied there, then told me that the workload in the preparatory classes was one of the highest in all the world—these weren’t the kinds of things you’d say unless you’d read them the night before on Wikipedia.

“I’m sure she’ll get in wherever she wants,” Denise said. I said I didn’t think Simone doubted that either.

Denise didn’t eat any of my rice, but that night at dinner, I still asked my mother if I could skip school and go to a funeral on Thursday.

“Who died?” she asked.

“A friend’s grandmother,” I said.

“That Dennis friend?”

“Actually, it’s Denise.”

“Oh, I see,” my mother said. “And did you know Denise’s grandmother at all?”

I lied and said I’d seen her around school a couple of times, a nice old lady.

“And you want to go to that funeral so you can pay your respects to the nice old lady or for moral support of the younger lady?”

I thought maybe Aurore had told my brothers that I’d gone to bed with a girl—they’d been looking at me differently the last few weeks, and now they looked almost interested when my mother said “the younger lady.”

“I don’t know.” I shrugged. “Does it matter?”

“I don’t think funerals are such great activities for teens, that’s all,” my mother said. “I’m just making sure you’d go for the right reasons.”

“And which of the two is the better reason to go?” I asked. “The dead person or the living person?”

It was a smarter argument than I’d thought. In fact, I hadn’t even thought about it as an argument, I’d just said it mechanically, earnestly, believing there would be a correct answer to my question and that someone around the table would give it to me. But no one said anything, and I realized I’d been deep by accident. I shouldn’t boast, though. I guess pretty much everything one said in a conversation about death came out with extra meaning.

“Maybe if one of your sisters came with you,” my mother ended up saying. “To make sure you’re okay…Aurore?”

Aurore looked up from her plate, surprised, it seemed, to be visible.

“Why would I go to Dory’s friend’s grandmother’s funeral?” she asked.

“Come on,” my mother said. “He went to your PhD defense.”

“I’m not saying I wouldn’t go to Dory’s funeral,” Aurore said.

“I’ll go with him,” Simone offered.

“But the ceremony is going to be in a church,” I told her.

“Of course it’s going to be in a church. Everyone’s bloody Catholic around here. So what?”

“Nothing. I thought you’d mind. You hate churches.”

“I hate the Church, it’s different,” Simone said. “People can go to church though, obviously, as long as they don’t try to sell it to me.” She paused there and added, matter-of-factly, “Mom goes to church sometimes. Who cares?”

My mother didn’t say anything. I didn’t know when her churchgoing had stopped being a secret. Maybe it had never really been one.

We were still eating when Berenice called to say she’d been accepted into a PhD program in Chicago. My mother picked up the phone in the kitchen all cheerful but her face turned to worry right away. “But you already have a PhD,” we heard her say into the phone, in the same tone actors used in movies when their character couldn’t make sense of someone’s death and said, “But he was so young!”

I don’t know what Berenice’s response to that was exactly, we couldn’t hear her part, but the way the phone call was summed up to us when my mother sat back at the table was that Berenice had said American PhDs were much more competitive and prestigious than French ones. Aurore didn’t pick up on that. Leonard didn’t either, even though he was in the middle of writing his own dissertation. There was a moment of silence. We all looked down at our noodles.

“Climbing back up the funnel,” Simone said. She said it to me, specifically, but loud enough that everyone around the table could hear, yet no one asked what funnel Simone was referring to. Maybe they were all familiar with the funnel image and were just picturing themselves in it, how close they were to the noose.

“Why am I still eating this?” Aurore said after a while, under her breath. “I’m not hungry anymore.”

“What time’s that funeral at?” Simone asked me.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Sometime in the morning.”

Simone noted it would be the first time she’d skip school for a reason other than being sick. “I guess it’s about time,” she said.

She only had two months of high school left.

The funerals I’d been to before hadn’t lasted more than half an hour, but Denise’s grandmother’s was near PhD defense in length. Everyone had something to say about her, and then there were prayers and songs. I tried to pay attention when Denise went up onstage for her eulogy, but her voice was so frail, and Simone and I had sat so far back, almost by the church’s door, that it was hard to follow. She talked about how her grandmother would never know the end of a soap opera she’d been watching every day for more than twenty years, and how painful that was to think about. About how no matter how old you were when you died, you always left unfinished tasks behind. I glanced at Simone while Denise spoke, to see whether she was repressing laughter or rolling her eyes. Simone’s physical reactions to speeches usually helped me know what I should think of them. Simone was actually involved in Denise’s words. When Denise said that her grandmother, knowing she didn’t have much time left, had stopped reading new books because she couldn’t stand the idea of dying in the middle of one without ever finding out how it ended, and that she’d spent her last weeks rereading the books she’d loved, Simone even nodded.

When we gathered around the hole for Denise’s grandmother, the grave diggers were on their cigarette break, ten or so graves away, waiting for us to leave to finish the morning job. I wondered if they were ever told about the people they dug holes for—how old they’d been and how they’d died—and if that determined the distance at which they thought it was okay to take their cigarette breaks. They hadn’t stood that close to us at the father’s funeral.

“What should I tell Denise?” I whispered in Simone’s ear as the undertakers lowered the casket with ropes. “Condolences or congratulations on her eulogy?”

“That guy is not doing it right,” Simone said, looking at one of the four pallbearers. “He’s standing parallel to the grave. He should be diagonal. He’s going to throw his back something nasty.”

“How can you tell?”

“Or throw himself down in the hole with the coffin.”

She seemed disappointed when nothing dramatic happened to the pallbearer. She clicked her tongue behind her teeth and glanced at her watch. She could still make it to philosophy class, she said.

“You’re supposed to stay with me and make sure I’m okay,” I said.

“Are you okay?” she asked. I said I was.

After Simone left, I went up to Denise and told her how much I’d loved her eulogy.

“Won’t bring Grandma back,” Denise said. She was in worse shape than when she’d just found out about her grandma’s being dead.

“It didn’t smell like anything,” she said, and at first, I didn’t understand what she meant. “You said there were dead-body smells that came out of the coffin, but it just smelled like church and incense.”

I’d never seen Denise cry and, like I said before, wouldn’t have bet on its being possible. She wasn’t shy about crying though, didn’t wipe her cheeks or hide her eyes—she kept them open and fixed on me. I put a hand on her arm. I could’ve closed my hand around it and touched index finger to thumb it was so thin. She didn’t like the contact and shook it off.

“I thought I saw your sister,” she said.

“She couldn’t stay. She told me to give you her condolences.”

“How sweet of her.”

People started leaving the cemetery but Denise wanted to stay and watch the grave diggers fill the hole. I sat with her on the next gravestone, that of a man who, according to the engraving, had died on a cruise. As the four men shoveled soil into the hole, I noticed Denise’s lips were moving, and when they stopped moving I asked what kind of prayer she’d just said.

“What do you mean what kind?” she said.

“I mean, what was it? What did you ask for?”

“It’s not like that,” Denise said. “You don’t ask for things.”

“I see,” I said, although her answer confused me. I’d always thought the point of believing in God was that you got to ask him things and see if you’d done good by him, if he loved you back and if your faith was real depending on whether he gave you the things you’d asked for or not. I took a little box of dental wax out of my pocket and started to roll some between my fingers. The inside of my lower lip felt ripped, rough and salty; the braces kept getting caught in the flesh.

“Did everyone tell you to be strong, after your father died?” Denise asked.

“No one really told me anything,” I said. Images of the father’s toothless period started rushing through my head. I pushed them away as I stuck the wax to my lower braces.

“It’s such bullshit,” Denise said. “They say ‘don’t be sad,’ and ‘it’s the way of life’ and all, that I should be strong, and that ‘it’s so easy to let yourself go’ while it takes courage and strength to choose to be happy and hold on to the small pleasures of the present…as if suffering was something weak people did, you know? I don’t get that.”

“They worry about you,” I said.

“Courage my ass. It doesn’t take courage to be in the moment. What really takes guts is to live each day as if you were going to hang around for the next ten years at least. Account for something. Live up to something. Now, that is hard. That requires a little more pondering and reflection, a little more strength.”

The wax provided immediate relief. Not only did it protect my lower lip from more brace spearing, but it numbed the preexisting pain right away. The box said it was the cold-mint flavor of the wax that did that. Very few things in life provided immediate relief, I thought.

“Simone—she also thinks the present is dumb,” I said. I refrained from telling Denise about the funnel theory.

“Of course it’s dumb. What’s there to enjoy?”

“Well I guess you don’t like eating much, so that takes a lot out of it,” I said.

The grave diggers were working at the hole cautiously, like there might be a chance Denise’s grandmother would wake up and complain about the noise.

“You could run away with me next time, if you want,” I said. I didn’t mean it. “We could go to Paris or something.”

“Really? We would stay at your sister’s?”

I tried to drown the offer I’d just made under a lot of words, to divert Denise’s attention.

“Berenice is moving to America next year,” I said. “She’s going to get a second PhD.”

“But if we go to Paris before summer break,” Denise said, “she would still be living there, right?”

“Her apartment is very small. A bedroom, really. She doesn’t have money for more. She lied about having a good job. I mean, she got fired from her good job a long time ago.”

It was the first time I told anyone a secret I’d promised to keep, but I didn’t feel bad about it. My family’s secrets were not really interesting.

“Well, we’ll find somewhere else to stay then,” Denise said. “When are you going next?”

I mumbled something about Easter. It seemed far enough away. I didn’t think Denise would forget my invitation by then but I was pretty sure she would chicken out, realize she needed her therapist and her meds, and in the meantime, there was no harm letting her dream of a Paris trip a little.

“I’m sorry I lied about the smells,” I said.

Most of the replies I got to my Internet ad were from older men who thought the ad was for a whole family to adopt. One of them couldn’t have children, he explained. He’d been left by the love of his life twenty years before because he “couldn’t conceive.” I wondered if that meant he was impotent. It felt insensitive to ask.

His name was Daniel, which I thought was boring, but in a good way, like he would be fine doing the crosswords while my mother read the rest of the newspaper. He wanted to see a picture of her and I described her the best I could—there was a picture of her on the Internet now, because she’d been featured in an article on the city hall website about what people randomly picked on the street thought about the new bike lanes in the center of town, but the picture didn’t do my mother justice, I thought, and I preferred not to send Daniel the link. I told him she was ready to date again but didn’t know it yet, and that he should wait for her outside her office one day (I gave him the address) and pretend he and I had never corresponded. I told him my mother liked orchids, any movie by Jacques Tati, and the color black. The ball was in his court.

Later that week, my mother came home from work with him. I immediately understood that she’d figured I’d dug him out of the Internet and brought him back to teach me a lesson, but Daniel thought she’d invited him over out of genuine interest. He couldn’t believe how well his moves were working.

“Dory, this is my friend Daniel,” my mother said. “Daniel, this is my youngest son I was telling you all about.”

“Very nice to meet you, young man,” Daniel said, and he actually winked at me.

“I invited Daniel for dinner, I hope you don’t mind.”

Daniel looked older than he’d said he was. I guess my mother, to him, was young.

My mother called all my siblings to join us in the living room and welcome our guest.

“Daniel, why don’t you tell my kids all about the book you mentioned working on while I go fix us some drinks?” she said. She disappeared into the kitchen and left us alone with Daniel. Daniel did as he was told and talked about his passion for photography and his ongoing project, a whole book made of pictures he’d taken and compiled over the years of clouds assuming all sorts of poetic shapes.

“What the hell is a poetic shape?” Simone asked, but Daniel only offered her a little laugh for an answer, as if Simone were being cute, too young to possibly understand the term poetic.

“I suppose you must be a great Ansel Adams fan,” Jeremie said.

“Well ain’t that funny!” Daniel marveled. “That is exactly what your mother said! I’d better check that fellow’s work…You gotta keep an eye out for the competition.”

Daniel retrieved a piece of paper from a pocket and seemed happy to take note of the name, unaware that Jeremie’s spelling A-N-S-E-L for him was the last time he would ever hear his voice.

“So when you say you have a passion for photography, you mean you’re passionate about using a camera, the technology of it, but you’re not that interested in the history of the medium,” Leonard said.

As far as I could tell, Leonard wasn’t trying to be mean, but his remark made Daniel uneasy. He glanced at me for support. I had nothing.

“Well I do enjoy the work of certain contemporary photographers,” he said, “like uh, from National Geographic and such.”

“Would you say your approach to photography is more autobiographical or metaphorical?” Simone asked.

“I’m not sure I understand what you mean,” Daniel admitted.

“Well it’s obviously not documentary oriented. What gets you to take a picture of one cloud and not another?”

Daniel seemed to pull himself back together a bit, like he’d heard that question before and had worked out an answer over time.

“I find myself more attracted to cumulonimbuses,” he explained. “They draw the most dramatic shapes, whole scenes even, sometimes, if you look closely and keep an open mind.”

“So it’s some sort of an imaginary approach,” Simone said, more like a note to herself than anything else. Daniel looked satisfied to have a new word to talk about his artistic process and agreed with her.

“And have publishers shown any interest in your work yet? Galleries?” Aurore asked.

My mother came back before Daniel could answer, carrying a bowl of Provençal olives and a couple of golden drinks. Daniel seemed relieved to see her and moved to his right on the couch as she handed him his drink, to make some room for her, but she didn’t notice and went back to the kitchen to grab two extra chairs, one to serve as a table for the drinks and olives, the other for her to sit on.

Daniel went at the olives like they could provide him with clever answers to my siblings’ questions. Every time he was asked something, he took an olive from the bowl and ate it before he would give a response. He tried to shift the conversation at some point and asked us all if we had boyfriends or girlfriends. He seemed delighted to find out none of us did. It gave him the opportunity to slide in a fact he thought we’d find witty and amusing.

“Aha!” he said. “All smart and good-looking, and yet all single! I guess the great misunderstanding between the sexes hasn’t skipped a generation! Did you know that in some Indian tribes, men and women actually spoke different languages? I’m not kidding you guys.” No one had accused him of such a thing. “They couldn’t even agree on grammar!”

There was hope, I thought. Daniel knew something, and it was something that I’d personally never heard before. Different languages for men and women, within the same society? That sounded quite promising. Maybe we could last all dinner on that topic and have a good time.

“Yes,” Leonard said. “Some tribes do have different languages for men and women. Except they understand each other and the men address the women in the women’s language, which also happens, most of the time, to be the maternal language. The presence of two different languages doesn’t necessarily mean incomprehension between people, or inability to communicate. Think about those regions where everyone speaks two languages, like Catalunya, for instance. Kids are just raised bilingual. If anything, it is a tremendous advantage for them on a cognitive level. And you could actually argue that men and women learning all about the subtleties of the other sex’s language helps them reach a better understanding of each other.”

Daniel grabbed another olive and thought about Catalunya.

“I guess I’d never looked at it that way,” he said.

“Where did you go to school?” Simone asked.

With that, my brothers and sisters regained control of the conversation and Daniel swallowed another olive. The olive situation was reaching a critical point. A few years before, Berenice, who was then already fluent in Spanish, had introduced us to a saying Spanish people had about the last slice of pie in the dish, the last piece of bread on the table, the last olive in the bowl: they called it the slice, or the piece, or the olive, of shame. Shame is what you were supposed to feel if you grabbed and ate the last piece of something, and the only way to make it less shameful was to acknowledge that you were conscious of grabbing the shameful item, or to publicly state your intention to do so in order to allow a chance for someone who wanted it more than you to make him- or herself known, which was something that never happened because most of the time people were happy to let another person deal with the shame. My parents had loved the idea. “Shame is a good thing,” the father had declared, “people should feel more of it more often,” and we’d adopted the Spanish saying without reservation. Something we had only considered vaguely impolite became shameful through the magic of a foreign proverb. One that Daniel was obviously not familiar with. Everyone was looking to see if he would eat the olive of shame without mentioning it. If he asked whether one of us wanted the olive, he would get a pass, I thought, but I wanted him to make a joke about it (the father, for instance, would’ve sliced the olive in two to let someone else get the half olive of shame), because a joke would surprise my siblings and possibly raise my mother’s interest. When he took the last olive in the bowl, he only looked disappointed there weren’t more. Simone shook her head judgmentally, and there were some unspoken I knew its around the living room. All Daniel saw was that the end of the olives meant it was time for dinner.

I didn’t say a word at the table, remaining a silent witness to my siblings’ catastrophic evaluation of Daniel. They inquired about his politics, his taste in books, his hobbies. I wanted Daniel to shine, to have anecdotes about once meeting a famous writer, invent one if needed, but he seemed incapable of sharing anything of interest. I wondered if one could really reach Daniel’s age and not have a single compelling story to tell.

After he left, thanking us for a lovely evening, Simone noted it had been a while since we’d had a condescension fest. I felt I’d been at the center of that particular one.

“Dory really is to thank for tonight’s entertainment,” my mother said.

“How did you meet that guy?” Aurore asked.

“My guess is through the magic of the Internet.” My mother was staring at me. “Am I right, Dory?”

“He looked smarter in his profile picture,” I said in my defense.

“I believe you were fooled by the white hair,” Simone said.

“By the way,” my mother asked me, “how old do you think I am exactly?”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“That guy was like seventy years old.”

“He looked like Alfred Stieglitz,” Aurore noted.

“You should’ve told him that.”

“And spelled the name out for him.”

I apologized again.

“It’s all right, honey. At least your brothers and sisters had fun.”

That night, my Internet privileges were revoked indefinitely.

On Sundays, I got bored. Not the way Simone used to get bored as a child (because there was no school on Sundays) but because Sundays made it even more obvious that everyone in our house was capable of finding ways to entertain themselves but me. Years earlier, our mother had tried to get us interested in gardening. She’d failed instantly with my siblings, whereas I’d planted tomatoes to make her happy. “Tomatoes are easy,” she’d said, but nothing had ever come out of the ground. I’d never attempted planting anything again, but I’d maintained the habit of checking the yard on Sunday mornings. I picked up dead leaves, mowed the lawn. I didn’t mow the lawn much, actually. It was hard work, and no one noticed or cared whether I did it or not, but I looked at how much the lawn had grown over the course of a week. Because our yard was the barest one in the neighborhood, save for the cherry tree, which could sustain itself without human help, my weekly inspection was not much more exciting than the indoors boredom I was fleeing. It was equally boring, in fact, but the silence of the yard was less heavy than the one in our house. There was hope it could be broken.

Our yard looked out on a paved alley and then across it onto another yard, in which all sorts of vegetables and flowers grew. The reason I only hung out in our yard on Sunday mornings and not in the afternoons was that I knew the owner of that perfect yard tended to it on Sunday afternoons, and I didn’t want him to see me and be sad for me for having a yard that sucked. I didn’t care that it sucked, and there’s nothing worse than people pitying you for things you don’t even yourself consider upsetting.

There wasn’t a lot of traffic in the alley but to some people it was a shortcut to somewhere, or a way to pay your boy- or girlfriend a backyard visit without the whole town’s knowing about it. The ones who used the alley as a shortcut said hello, and the other ones pretended I wasn’t standing in my backyard and kept on running to their secret destinations, convincing themselves I hadn’t seen them. That Sunday, Porfi approached our fence, waving. Porfi wanted to be called by his last name, Porfi, but his first name was Charles. “Can I come in?” he said.

I walked to the gate, unsure I even knew how to open it. It was locked and there was no key in the keyhole.

“What do you want?” I asked through the bars of the gate. I’d known Porfi all my life, but our only interaction so far had occurred in grammar school, when I’d asked him if he was myopic and he’d gone running in tears to our teacher. “He called me myopic! He called me myopic!” he’d cried. “Well, are you myopic, Charles?” our teacher had asked him, and Porfi’d admitted he didn’t know. “You do wear glasses,” the teacher had observed. “You might very well be. And myopic is not an insult. Not last time I checked it wasn’t.” Porfi had replied that what made an insult an insult was the way it made you feel when you heard it, and the teacher had said, “I really don’t think you’re right about that,” and that had caused Porfi to resent her as much as he resented me. I’d always assumed Porfi hated me because I’d called him myopic that day. He’d always picked a seat as far away from me as possible, within the limited number of seats he and I were allowed to choose from, given we were both myopic and asked by our teachers to sit in the front row with the rest of the vision-impaired.

“Are you and Denise Galet a couple?” Porfi asked me that Sunday without further introduction. There was a combination of fear and immediate relief in his voice as the words freed themselves. He’d done his part expressing his interest in Denise. The next step was for me to handle. That he was in love with Denise came as quite a shock to me. I’d always assumed no one even liked Denise—she openly despised most of those who’d tried to come into contact with her over the years—or even noticed our existences anymore, but I tried not to look too surprised. I didn’t want to risk insulting Porfi’s feelings.

“We’re not a couple,” I said as quickly as possible, in case hesitation on my part could change his mind about loving Denise. I’d gotten to like Denise somewhat, but the idea that someone else wanted to share recess with her, try to make her happier, was a load off my shoulders. Denise could be quite a downer sometimes.

Porfi carried with him a spiral notebook in which he’d glued pictures he assured me were pictures of Denise, but he’d taken them from such a distance, and with such shitty cameras (those disposable ones you could buy for a few bucks at the supermarket, he admitted), that you really had to believe it to see it.

“I took that picture of her just outside school last week,” he said, pointing at a dark shadow the size of my pinky nail that he assured me was Denise leaning on one of the bike racks outside the school’s main gate. “She’s always very early,” he explained. “Even when her first class is at eight a.m., she gets there before the gate is even opened. The janitors never open the gate before seven fifty.”

“Is that so?” I said.

Porfi nodded, a serious nod. He’d learned that fact the hard way. On the next page of his notebook, he’d taped a copy of Denise’s weekly schedule.

Pages of the notebook had titles like “Books Denise Has Read,” with pictures of dust jackets Porfi had likely cut out from catalogs. The “Known Relationships” page only bore Denise’s parents’ names and mine.

“How long have you been in love with Denise?” I asked.

“Almost since I started junior high,” Porfi said. “I spotted her feeding the birds, you know, with you, and I thought it was a very cute thing to do. But I could never talk to her. She’s always running right out of class when the bell rings, to meet you in that staircase, and then she gets back at the last minute. I thought about maybe passing a note to her in class, starting a conversation that way, but I don’t know. It seems corny. And other people could intercept it, and I don’t think Denise would like that one bit.”

“What do you like about her?” I said. “Aside from her feeding the birds and stuff.”

“Well I don’t know. She’s smart, I guess. She reads so many books.”

“I didn’t know you liked reading,” I said.

“Well I don’t. But I like that she likes it. And I’m not as smart as her, but I have other skills.”

“Like what?”

“Like mechanics, electricity. I’m good at repairing things. Do you know if there’s something Denise needs to have repaired? Like a lamp or something? I’m good with lamps. That could be a good way that you could put us in contact,” Porfi said. I admired him for being so open about his feelings.

“She never said anything about a lamp,” I said. “But I’ll ask.”

“Don’t be too obvious about it, though. I don’t want to become a joke between you guys.”

“Why would you?”

“I don’t know. People are cruel. I’m sure you can be too.”

I wondered if he was referring to the day I’d called him myopic. I thought about saying, like I’d said at the time, that I had meant no harm asking about his eyesight but had merely been seeking information since I’d been told myself that I would soon need glasses, but then this guy Victor came out of nowhere on his bicycle and nearly ran Porfi down. The notebook where Porfi had compiled all of his Denise knowledge slipped from his hands and fell to the ground, open.

“What are you guys doing, talking between bars?” Victor yelled at us, although he’d turned around and stopped his bike a mere yard from where we stood. Porfi had managed to pick up his precious notebook without Victor’s seeing what it contained, and he seemed grateful to all gods that the notebook had made it back safe to his arms, as though it could’ve broken in the fall.

“Are you like a couple now?” Victor went on. “Are the bars a metaphor for the prison of gayness you always felt creeping up around you, depriving you of a chance to ever fit in?”

“Get lost, Victor,” Porfi said, and his confidence impressed me, considering the fact he was holding something against his chest, first of all, in a very girly manner, something that, second, could’ve caused Victor to make fun of him for eternity if he ever discovered what exactly it was. Victor was in my German class, because his parents thought he was smart and German was the choice of smart kids, but Victor wasn’t smart.

“Chill out, ladies,” Victor said, “go get yourselves a sense of humor,” and he went on his way.

“Well,” I told Porfi after Victor had disappeared at the end of the alley. “That was brave of you. Not quite sure it convinced him we weren’t flirting, though.”

“It’s fine. I prefer Victor believing I’m gay to knowing I’m in love with Denise. People don’t like Denise very much.”

I wanted to say I would’ve preferred Victor to know the truth than believe I liked boys, but then why hadn’t I said anything in my own defense?

“I guess she’s too…unconventional for people,” Porfi went on.

“She’s unconventional all right,” I said.

“Hold that thought!” Porfi said, licking his index finger to flip through his notebook ’til he landed on a blank page. He took a pencil out of the chest pocket of his overalls; pressed the lead to the top left corner of the page, ready for dictation; and raised his black eyes back to me. There was a minute of silence.

“What do you want me to say?” I ended up asking. “It seems like you know more about Denise than I do.”

“Don’t be so modest. I don’t even know what you guys talk about all the time. Like, what are the topics of conversation that she likes? You have to help me out here.”

I thought about all my conversations with Denise, tried to see a pattern. Porfi mistook the time I spent coming up with one for reluctance to share my knowledge.

“What do you want in exchange?” he said.

“In exchange for what?”

“Tips. To make Denise like me.”

“I don’t want anything in exchange,” I said, and it was the truth. I just didn’t know what to tell Porfi that could help his courtship. There were a certain number of things I knew about Denise—the medication and dosages she took for her depression and anxiety, that she’d had a crush on a girl named Juliette in a video a few years before, that her favorite movie was Au Revoir les Enfants—but it seemed like they would all be turnoffs to Porfi. I was looking for a way to be fair to Denise, and it kept eluding me.

“Come on,” Porfi said. “We all want something. I have a skateboard I don’t use that I could give you. Dirty magazines.”

I pretended to be interested in those because you had to, if you were a boy, but when Porfi listed the titles I lied and said I had them all already.

It wasn’t only that I didn’t want anything in exchange for my tips, I realized. I just wasn’t sure I wanted anything at all, and the thought made me dizzy, the way I felt before a test I hadn’t studied enough for. I looked behind me at the yard as if it could help me figure out what I wanted from life. It didn’t.

“Do you speak German?” I ended up asking Porfi. I was sorry for myself for being unable to think of anything more exciting, so I tried to be mysterious about it. The way I said it, you could have believed I was assembling a team of spies for a secret mission in Germany.

“Of course I don’t speak German,” Porfi said. “I have a little Spanish though. My grandfather was from Argentina.”

“That won’t work,” I said, still looking at the bare rectangle of dirt where I’d once tried to grow tomatoes.

“Does Denise want a German-speaking boyfriend?”

“No,” I said. “I was asking for myself.”

“What do you need a Kraut for?”

I turned my face back to Porfi.

“Would you be interested in skipping school with Denise and me to go to Paris around Easter?” I asked.

Porfi said that anything that could get him closer to Denise, he was ready to try.

“I’ll tell her you want to come with us then,” I said. “I will leave the whole thing about how you love her out of the conversation at first, see how she reacts.”

“Test the waters,” Porfi said.

“Right. I’ll tell you what she thinks.”

“Thanks, man,” Porfi said, and then he extended his hand through the bars of the gate for me to shake.

“Of course,” I said.

“And you know what?” he said as he was getting ready to leave. “That old lady there, Daphné Marlotte. She speaks German, I think. Her husband was a Nazi or something, back in the day. Or she was. If that helps you any.”

“Well obviously, he was kidding,” Denise said after I told her all about Porfi’s visit.

“He looked pretty smitten to me,” I said.

“Don’t use that word. It’s disgusting.”

“Fine. He looked honest. And he had all these pictures of you.”

“That’s so creepy. Tell him I don’t want him to take any more without my permission.”

“So you would agree to having one taken with your permission? I’m sure he would love that.”

“Don’t be silly,” Denise said.

I might’ve only wanted to see things that weren’t there, but it seemed to me Denise was trying to hide being flattered that a boy was interested in her behind her feigned disbelief and her real disappointment that the boy in question was only Porfi.

“What else should I tell him?” I said. “Would you agree to him going to Paris with us?”

“That part’s up to you, really,” she said. “You’re the brain behind the whole Paris operation.”

The rest of recess we talked about Denise’s impression that she had two different heads.

“I often feel like I have a smaller head inside of this one,” she said, “that people don’t see. It is smaller but it has more things in it than the other one and so it keeps trying to repel the outer head and take its place.”

“You’re sure it’s not just a headache?” I asked, because it sounded mostly painful.

“You really can be quite dumb,” Denise said.

“That’s exactly why you should start seeing other people,” I said, and then she told me I had a piece of breakfast stuck in my braces, which I’m not sure was true (Denise used that line any time I said something she didn’t want to respond to). She asked me what I thought happened to kids who died with their braces on.

“Do you think they get buried with them? That seems wrong for some reason, but I doubt they have special orthodontists for the dead,” she said.

I said I didn’t care because I didn’t plan on dying too soon.

“Well I don’t plan on wearing braces,” she said.

“You always manage to keep the mood so light,” I said.

“I was kidding,” she said. “See? You can never tell if someone is kidding you or not.”

“I’m sorry I can’t always tell when you’re seriously suicidal or just trying to entertain me,” I said.

I wasn’t really apologizing, but Denise took it to heart and said it was okay, that she knew she was the one who should be sorry. “I know I’m a nightmare,” she said. She was good at turning a thing you said into yet another example of how complicated she was, but I knew that she didn’t get pleasure in doing that either. I also knew the next thing she would say would be a peace offering, something she didn’t really mean but believed I would be happy to discuss.

“Does Porfi really keep track of everything I read?”

Denise didn’t meet me at recess for days in a row and I thought Porfi had to be doing something right. Either he had built up the nerve to go up to her on her way down to our staircase or Denise, now aware of being watched lovingly, had lingered a little longer than usual in the classroom to make it easier for him and he’d taken his chance. I didn’t want to feel lonely, I just wanted to be happy for them, but it’s not that easy controlling your feelings and I’d gotten used to having someone to talk to, even if only about how little there was to look forward to in life. I wondered if there was a chance I was in love with Denise, but even in the privacy of my own thoughts, the idea seemed ludicrous and I couldn’t consider it seriously for more than a few seconds.

On the third day without Denise, I missed talking to someone so much that I went up to Simone after school to see if she wanted to have an interview. She was working at her desk and dismissed my request. “I appreciate that you’re taking the biography seriously,” she said, “but when I’m busy, you can just do some research. Go interview other people about me. See what they have to say.”

Aurore and my mother were out and my brothers’ door was closed as usual. I stood in front of it and tried to come up with a way to disturb them without their seeing it as a disturbance. My brothers scared me a little. I felt I had to have something important to say if I was to request their attention. From a very early age, my sisters had made me understand that I wasn’t as smart as them but that it didn’t matter, that I had other qualities, whereas I feared the reason my brothers never talked to me was because they didn’t think I was interesting enough. I’m not sure my sisters and I were close, but I knew my brothers and I definitely weren’t, and I couldn’t tell whether we never talked because we had nothing in common, or if it was because we never talked that we never found out if we had something in common. Their school grades seemed to suggest they were as smart as the girls, but they never mentioned their work or shared what they were learning. We didn’t even know what Leonard’s PhD dissertation was about, for instance. He just said he was working in a micro-sociological perspective. Jeremie studied music composition and whenever my mother asked how it was going he would just avoid answering by saying that music was an abstraction and couldn’t be talked about. Most of what they said was said in reaction to something one of my sisters had said, or had been said on TV. I’m not sure they needed attention at all, or that they could understand people who did, and that’s why I had no idea how to get theirs. I decided I would never find a way to sound interesting and found myself knocking on their door without a speech prepared. I couldn’t believe I was doing it. Jeremie sighed a weary “Come in” that suggested people knocked on their door all the time, which was not a thing I could say for sure had ever happened. Leonard and Jeremie were both at their desks, their backs turned to each other.

“Hi, guys,” I said.

They didn’t invite me to have a seat or anything, but I didn’t want to stay on the threshold, so I closed the door behind me and made my way to the center of the room to stand between the two of them.

“What do you want?” Leonard said. He’d rotated his desk chair to face in my direction.

“Well I’m working on Simone’s biography,” I said, “and I was wondering if you had anecdotes or stories about her that you would want to share with me. Or anything. I mean, we can talk about anything you want.”

Leonard squinted as if I’d said something complicated.

“I heard you got laid,” Jeremie said. He was still looking at his computer, and sound waves of different colors, but he’d taken one of his earphones out.

“I did!” I said, and regretted sounding the exclamation mark right away. I was excited that Jeremie was showing interest in something I’d done, but he must’ve thought I was just boasting.

“It wasn’t with a pretty girl, though,” I said in an attempt to undo the exclamation mark.

“Those who lose their virginity to good-looking girls are very rare,” Jeremie said. I thought he would expand on that, but he resumed adjusting sound waves on his screen, and for a while the clicking of his mouse was all there was to be heard.

“What exactly do you want to know about Simone?” Leonard asked me as I was about to sneak out and apologize for having interrupted their work.

“I don’t have specific questions,” I said, “but I think she’d like it if you had funny memories about her to share, how it was to see her grow, things like that.”

“She believed in Santa Claus ’til she was eight years old or something,” Jeremie said. “It must be a kind of record.”