The war at sea, May 1941

In early May of 1941, the crew of the Bismarck had been feverishly preparing for an inspection by none other than the German führer (leader), Adolf Hitler. Now he was here among them. Decks had been scrubbed, rails polished, uniforms pressed and the ship’s barber had worked his way through as many of the 2,100 men as time and his blistered fingers allowed. The visit to Germany’s greatest battleship was going well. The crew, whose average age was all of 21, were immensely proud of their new vessel. As Hitler passed their assembled ranks, they stood there, faces stiff with pride and overawed to be in the presence of their leader. Not everyone on parade was impressed with Hitler, though. As he walked by anti-aircraft gunner Alois Haberditz, the Nazi leader looked straight through him. Haberditz shuddered. Hitler had eyes as cold and pitiless as a shark.

The Führer, who had an almost schoolboy fascination with battleships, was taken on a tour of the ship. He seemed particularly interested in the Bismarck’s gunnery control system – a state-of-the-art computer mechanism which took in the ship’s speed and course and that of its enemy, wind direction and shell flight time. This produced changes of correction of aim at what was – by the standards of the time – lightning speed. Hitler also noted with pride the two huge swastikas – the emblem of his Nazi party – painted at either end of the ship, which served to identify it to their own aircraft.

Germany had a small navy, but her warships were the most advanced in the world, and the Bismarck was the pride of her fleet. A truly gargantuan war machine, over one quarter of a km (one sixth of a mile) long, and bristling with huge guns, she was unquestionably the fastest and best armed and protected battleship of her day.

Among the officials with Hitler on this tour of inspection were Bismarck’s two most senior officers. The Captain was Ernst Lindemann, a stiff, rather frail looking 45-year-old, who was never seen without a cigarette. In his official portrait, Lindemann stares out at the world with piercing, intelligent eyes, his blond hair slicked back on his head, with two enormous ears. But his stern and slightly comical look was misleading. His crew held him in both high regard and affection – some even referred to him respectfully as “our father”. He emanated both approachability and confidence, and being appointed captain of the Bismarck was the greatest break in his naval career.

Also sent to sea with Lindemann was the fleet commander, Admiral Günther Lütjens, together with 50 of his staff. Lütjens was a starkly handsome 51-year-old, bearing a passing resemblance to American film actor Lee Marvin. Lütjens, like Lindemann and many officers in the German navy, was not a great supporter of Hitler, and had tried to protect Jewish officers under his command. Right from the start of the war he had believed Germany would be defeated. Perhaps that was why he was such a forbidding man to be around, and it was said that he almost never smiled or laughed. Although he was a fine and experienced commander, he did not have Lindemann’s leadership skills, as subsequent events would show. Lütjens knew the British feared his powerful ship, and that they would do everything in their considerable power to destroy it. He, more than any man aboard the Bismarck, did not expect to return from this posting alive.

At this stage of the war, Britain was the only major European power still undefeated by the Nazis. Hitler, and Germany’s commander-in-chief of the navy, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, intended to use the navy to starve their isolated island opponent into defeat. Britain’s survival, after all, depended on cargo ships from her colonies and North America. So far this tactic was working. In early 1941, the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau had ventured out into the North Atlantic on raiding missions and sunk 22 merchant ships between them. Now, in May of this year, the Bismarck was preparing to do the same. The expedition was code named Rheinübung (“Operation Rhine”), and sailing out with the Bismarck was another modern ship, the Prinz Eugen. This raid would be different. On previous missions German warships had been told to avoid battle with the British Navy at all cost, and concentrate solely on destroying merchant ships. But now, so confident were the officers of the German High Command in their new warships, they had given permission for them to fight back if they came under attack.

Most of the crew, in their invincible youth and invincible battleship, had no idea of the horrors that awaited them. But a few more experienced ones had been aboard sinking ships, and were old enough to know that the British Navy was actually quite a formidable foe. Even Grand Admiral Raeder had admitted to confidants that the surface vessels in his navy (as opposed to his lethally effective submarine fleet) could do no more than take part in hit and run raids. They were heavily outnumbered by the British, who had always depended on their powerful fleet to keep control of their sprawling overseas empire and protect their trade. When Raeder heard that war had broken out with Britain, he greeted the news with resignation. “Our surface forces can do no more than show that they can die gallantly,” he declared.

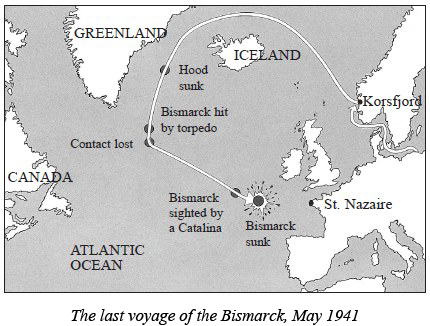

Almost from the start of their mission, Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were shadowed by British planes and ships – all carefully keeping out of range of their powerful guns. When news reached the British Admiralty that the two German ships had left Korsfjord, in Norway, to venture out into the shipping lanes of the North Atlantic, immediate action was taken. The Royal Navy ordered two of their own most powerful warships – Hood and Prince of Wales – to intercept them, and these ships slipped away from their Orkney base at Scapa Flow in the early hours of May 22. In overall command of this force was Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland, who sailed aboard the Hood. A grey-haired, distinguished-looking man, he had the air of a venerable BBC commentator wheeled out to present a royal funeral. Within a day, another great battleship, King George V, the aircraft carrier Victorious, and four cruisers, had also set off to join him.

The Hood was quite possibly the most famous battle cruiser in the world. Built in 1918, she was a handsome and formidably-armed vessel, a sixth of a mile from bow to stern. Hood had become a symbol of British naval power, and had a fearsome reputation. During training exercises, the crew of the Bismarck had frequently run through attack and resistance tactics, with Hood as their imaginary enemy. Now they were about to fight her for real.

Bismarck and Prinz Eugen took a course up past the north of Iceland, and through the Denmark Straits, which separate Iceland from Greenland. Here they sailed close by the huge sheath of ice which forms around the coastal waters of Greenland for most of the year. On the journey up, the two deck swastikas were hurriedly covered over with a fresh coat of paint. The only aircraft out here would be British ones – and such insignia would clearly indicate that the Bismarck was an enemy ship. It was in these chilly waters that the Hood and the Prince of Wales raced to intercept them.

This far north, during spring and summer, night falls for a few hours or not at all. In late May, dawn came before 2:00am, casting a pale grey light over a heaving sea, dotted by patches of fog and brief flurries of snow. Men stationed in lookout posts aboard the ships longed to scuttle back to the cozy fug of their cramped quarters, as a biting wind gnawed at their bones, and icy spray whipped over the bows to sting their numb faces. This desolate spot near the frozen top of the world was one of the most dismal places on Earth.

Aboard the German ships, crews were expecting an imminent attack. But they had no real idea how close the British actually were. The cruiser Suffolk had sighted them just after 11:00 in the evening on May 23. Alerted, Vice-Admiral Holland closed in at once. By 5:00 the next morning, he was expecting to sight his enemy at any minute. Sure enough, two ships were spotted at 5:30am, black dots 27km (17 miles) away on their northwest horizon.

On Bismarck and Prinz Eugen, the crews had spent an anxious night. There had been several false alarms as hydrophone (sound detection) operators thought they had picked up the incoming rumble of British engines. But it was a radio message from German headquarters, who had been monitoring British transmissions, that told them their enemy was almost upon them. Just after the message arrived, lookouts spotted two smoke trails from the funnels of the approaching British, on the southeast horizon. Even then, the Germans were not sure this was an attack. Perhaps they were still being shadowed by smaller vessels, who were just keeping tabs on them.

But by 5:50am it was obvious to Lütjens that the approaching ships meant to attack him. He sent a terse radio message to his headquarters: “Am engaging two heavy ships.” Then he prepared himself for the battle to come.

In all four ships, in an oft-rehearsed procedure, one ton high-explosive shells were hauled up to the huge gun turrets by a complex system of pulleys and rails from magazines deep inside the hull. In Bismarck and Hood, these monstrous projectiles were 38 or 41cm (15 or 16 inches) across, and were loaded into guns 6m (20ft) long and weighing 100 tons each.

Holland gave the order to open fire at 21km (13 miles), and almost at once all four ships began exchanging broadsides. At these distances shells would take up to half a minute to reach their target. It was just before 6:00am. So loud was the roar of their huge guns they could be heard in Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. But when battle began it soon became apparent that the Hood’s reputation had been undeserved.

Built just after the First World War, she had been given heavy steel protection along her vertical surfaces – when current warship designs assumed enemy shells would travel in low and hit her sides. Twenty years later, such assumptions no longer applied. By 1940 warships aimed their shells in high, arc-like trajectories, where they plunged down on top of decks and turrets. Here were Hood’s weakest spots. And the Bismarck’s second and third salvo had an astonishing effect on the British ship. Men aboard Bismarck and Prinz Eugen watched in astonishment as their much-feared opponent exploded like a giant firework, lifting the entire front half up out of the water, and breaking the battleship in two. A huge, strangely silent sheet of flame shot high in the air, as intense as a blow torch and so bright it could be seen over 50km (30 miles) away. Hood turned over and sank. In less than five minutes, in the bleakest of battlegrounds, Vice-Admiral Holland and all but three of his 1,421 crew died.

Prince of Wales veered sharply to avoid hitting the Hood. She was in deep trouble herself. Seven shells from Prinz Eugen and Bismarck had hit her, including one at the bridge which had killed everyone there but the Captain, John Leach, and two of his officers. Several of her main gun turrets had also jammed. Sensing another catastrophe, and with no chance of destroying either German ship, Leach ordered a speedy retreat.

Aboard the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen there was an atmosphere of euphoria. The crews had been led to believe they were aboard the most powerful warships on the planet, and events had proved this to be true. Hadn’t they? Yet the atmosphere on Bismarck’s bridge was strained. Lütjens and Lindemann had exchanged sharp words about the wisdom of going after the Prince of Wales. Even though she was an easy target, Lütjens had decided to stick to his original mission – sinking enemy merchant ships. He was not prepared to take any unnecessary risks.

And there was bad news too. Although Prinz Eugen had escaped unscathed, Bismarck had taken two shells from the Prince of Wales. Men had been killed and the ship’s medical bay was filling up with burned and scalded casualties. Most serious of all, a shell had sailed clean through the front of the ship close to the bow. It had not exploded, but had left a man-sized hole, just above the water line. As the Bismarck lurched up and down through the choppy ocean, the sea flooded in and drained out, gradually filling the surrounding compartments with 2,000 tons of water. Fuel lines had been broken, leaving 1,000 tons of fuel in the forward tanks cut off from the engine room, and the ship was seeping a sickly brown trail of oil. Part of the ship’s engine had also been damaged.

News of the Hood’s destruction caused a sensation across the world. British prime minister Winston Churchill would recall it as the single worst moment of the war. The British Admiralty issued a famous order “SINK THE BISMARCK”, and four battleships, two battle cruisers, two aircraft carriers, 13 cruisers, and 21 destroyers were dispatched to avenge the Hood. The man given the responsibility of hunting down the Bismarck was Admiral John Tovey, commander of the British home fleet. A small, dapper man, whose sharp, determined features gave him something of the look of a bull terrier, Tovey had considerable forces at his disposal, including his own flagship King George V.

Tovey’s first task was to ensure the Bismarck did not vanish from sight. The North Atlantic, after all, stretched for more than a million nautical square miles. Although she was still being shadowed by smaller British vessels, it would be easy enough to lose her.

On the morning of Bismarck’s first extraordinary day in action, the rain and drizzle eventually gave way to an occasional hint of sunshine, but the sea was still heaving. Lütjens and Lindemann had been considering their options. Their ship was losing fuel and taking in water. Although it still had full firepower, it now lacked speed – an essential attribute for its hit and run mission. Lütjens ordered the Prinz Eugen to break away from Bismarck and continue alone. He would take his own ship back to the port of St. Nazaire, France, for repairs. At their current speed, they should make the 2,700km (1,700 mile) journey in just under four days.

Meanwhile, the British made their first counterattack with Swordfish torpedo bombers from the aircraft carrier Victorious. These quaint biplanes looked like relics from the First World War, and they lumbered dangerously slowly through the sky. Bismarck fought off the Swordfish with ease – her AA (anti-aircraft) guns putting up a protective sheet of flame that prevented the planes from launching their torpedoes accurately. There was one hit, but it caused minimal damage. But, far to the south, another British aircraft carrier was hurrying up to intercept the Bismarck. The Ark Royal, and her Swordfish crews would soon prove to be far more deadly.

Sunday May 25 was Lütjens’ birthday. He had always believed he would die on this mission, and had resigned himself to the fact that this would be his last ever birthday. That midday he made a speech to his men – talking to them over the ship’s PA system – and something of his dark mood rubbed off on a crew still exuberant from their brush with the Hood and Prince of Wales.

“The Hood was the pride of England,” he told them. “The enemy will now attempt to concentrate his forces and set them on to us… The German nation is with you. We will fight till our gun barrels glow red and the last shell has left the breech. For us soldiers it is now ‘victory or death’.”

It was not a diplomatic choice of words – but even admirals are human, and Lütjens knew all too well what was coming. But he was too pessimistic. During the night of May 25 Bismarck had outrun her British pursuers, and when dawn came they had lost sight of her. But Lütjens did not know this. Later that day he sent a long, despondent message to German High Command. This was picked up by British radio trackers, who concentrated an aerial search in the area where they detected the signal. But even then, luck was still with Lütjens. Tovey’s fleet miscalculated his position – and assumed Bismarck was heading back to Norway, rather than France. They altered their own pursuit course accordingly.

It would be a whole 31 hours before the British found the Bismarck. Around 10:30 on the morning of May 26, observant members of the crew noticed an RAF Catalina flying boat circling just outside the range of their AA guns. By now the ailing battleship was approaching the Bay of Biscay. The port of St. Nazaire was a mere day or so away, as was the imminent prospect of both U-boat and air escort. Bismarck’s position was duly reported by the Catalina, and Tovey’s fleet altered course.

To the south the carrier Ark Royal was closing in fast, its huge bulk heaving alarmingly in the rough sea. Amid torrents of seawater that sprayed the flight deck, ground crews prepared the ponderous Swordfish bombers, loading heavy torpedoes to their undersides. In the middle of the afternoon, 15 Swordfish lumbered into the air. They did not expect to sink the Bismarck, but they hoped, at the very least, to cause enough damage to slow her down, so that pursuing British warships could catch up and attack. Slipping through low cloud, fog and driving rain, they pounced, flying just above the churning waves to unleash their torpedoes toward their target. If the crews of the Swordfish were surprised by the complete lack of defensive fire from the ship below, it did not cause them to pause and consider their target. All the torpedoes missed – which was fortunate for the Swordfish crews, because the ship they had actually attacked was the British cruiser Sheffield.

Amid huge humiliation and embarrassment, a second wave of 15 Swordfish was sent off into the slow falling dusk. This time, they found the Bismarck, still 1,000km (620 miles) from St. Nazaire. They moved so slowly they seemed to be hanging in the air. But they flew in so low, their wheels almost brushing the waves, that Bismarck’s guns could only fire above them. This time two torpedoes hit home. One caused only minor damage. The other went off underneath the stern, with a huge watery explosion that shot like a whiplash through the length of the ship. It buckled deck plates and bulkheads, and threw men to the floor or against metal partitions and instruments, with breathtaking violence. Above the site of the explosion, water surged into the ship with a vengeance, flooding the entire steering compartment. The sea burst through once waterproof compartments. It gushed down cable pipes that ran the length of the ship, to spurt out unexpectedly, far away from the site of the damage.

Aboard the Ark Royal, senior commanders listened to the wildly excited reports of their young pilots, and tried to sift fact from fiction to determine exactly what damage had been done. One pilot’s account seemed to indicate something extremely significant. After the attack, the Bismarck had been seen to make two huge circles on her course, then slow down almost to a halt. Clearly, her steering had been badly damaged. In fact, the rudder had jammed at 15° to port.

Aboard the stricken vessel desperate measures were called for. The Bismarck carried three seaplanes. Plans were made to remove the hangar door where they were stored, and weld it to the side of the stern, to counteract the effect of the rudder. But bad weather made such a scheme impossible.

Following the Swordfish attack, Lütjens sent another grim signal home: “Ship no longer steering.” German naval authorities reacted by ordering U-boats to head for the Bismarck’s position as soon as possible. But U-boats are not the swiftest of vessels, and there were none nearby. Informed of the Bismarck’s grim predicament, Hitler had a radio signal sent to Lütjens: “All of Germany is with you. What can still be done will be done. The performance of your duty will strengthen our people in their struggle for their existence.” It was not a message that offered any hope of survival.

Bismarck’s crew passed a long, dreadful night – each man wondering whether he would live to see another dusk. Many had nightmares, and men woke screaming or sobbing. When word spread that the rudder had been put out of action, the older members of the crew took this to be a death sentence. Later in the night, permission was given for the crew to help themselves to anything they wanted – food, drink – a tacit admission that the ship was doomed. But Lindemann had assured them U-boats and aircraft were heading out to protect them, and some of the younger sailors still held out hope that they would survive after all.

During the night, Lindemann ordered the engines to stop. When the chief engineer requested they be started again, Lindemann replied, “Ach, do as you like.” After five nights with virtually no sleep, and all the stress and worry of commanding a ship in a now impossible situation, he was a man at the end of his tether.

To keep the crew from brooding overmuch about the battle to come, records of popular songs were played over the ship’s PA system. But such obvious psychological tactics failed – the songs reminded the men too much of girlfriends or wives and families back home. Lindemann had also come up with the ruse of getting men with no immediate job to do to construct a dummy funnel of wood and canvas. The idea was to change the Bismarck’s silhouette, so that enemy ships or aircraft would think it was another battleship, and leave it alone. This was some considerable task, and men were kept busy painting the canvas and building the scaffolding structure right through the day.

At first light on May 27, the day Bismarck had hoped to reach the safety of a French port, Tovey and his fleet closed in to finish the job. Along with his own flagship King George V, was the huge battleship Rodney, the cruisers Norfolk and Dorsetshire, and several others.

Aboard the Bismarck, exhausted lookouts saw two massive ships heading straight for them. Tovey intended the sight of King George V and Rodney boldly closing in to unnerve the German crew, and it worked. The battle that followed, which started with a salvo from Rodney at 8:47am, was unspeakably grisly. As they homed in, the British ships took carefully timed evasive action, darting one way then another, to avoid the Bismarck’s powerful guns.

This time luck was with the British, and few of the Bismarck’s shells found their mark. By 8:59am King George V and Rodney were both firing steadily. Four salvos a minute were falling around the Bismarck, which was now completely obscured by smoke and spray from the huge towering columns of water sent into the air by near misses.

At 9:02am a shell from Rodney hit Bismarck near the bow, and the entire front end of the ship was momentarily swallowed by a blinding sheet of flame. This one shot, ten or so minutes into the battle, was the most crucial of the day. After that, Bismarck’s two front turrets fired no more. In one, the huge guns pointed down to the deck, in the other, one barrel pointed up, and the other down. In that one explosion, perhaps half the ship’s crew had been killed. Only one man from the entire front section survived the battle.

Bismarck may have been the most technologically advanced battleship in the world, but she was completely outgunned. For a further hour, hundreds of shells fell on her. On deck or below, men were blown to pieces or burned to death, as her interior turned into a blazing deathtrap. As the British ships drew closer, Bismarck’s exceptionally effective construction merely made her destruction even more prolonged. As the shelling continued, fierce fires blazed all over her deck and superstructure, and Bismarck began to list to port.

By 10:00am the British ships were close enough to see streams of men leaping into the sea, to save themselves from the flames and still-exploding shells. When it was obvious that the crew were abandoning their ship, Tovey ordered the shelling to stop. Burkard Freiherr von Mullenheim-Rechberg, fire-control officer for the Bismarck’s after guns, emerged from his battle station and surveyed the damage. “The anti-aircraft guns and searchlights that once surrounded the after station had disappeared without a trace. Where there had been guns, shields, instruments, there was empty space. The superstructure (upper) decks were littered with scrap metal. There were holes in the stack (funnel), but it was still standing…”

Von Mullenheim-Rechberg could see that the ship was slowly capsizing. Amid the carnage and rubble, men were running around, desperately searching for ways to save themselves. Such was the destruction on the decks that not a single lifeboat, life raft or float remained. Amid the smoke and ruin, von Mullenheim-Rechberg saw doctors busy attending to the wounded, giving them pain-killing morphine jabs to ease their agony.

Many men were trapped inside the ship, as fires cut off escape routes, and shells buckled hatches which now no longer opened. Some were able to escape by climbing up shell hoists, wiring shafts or any other kind of duct large enough to take a man. Many others gave up hope and sat where they could, waiting for the ship to go down. But still the Bismarck stayed afloat.

During the morning, Tovey was expecting both submarine and air attack by German forces, and was anxious to leave the area as quickly as possible. He ordered any ship with torpedoes left to fire them at the Bismarck, to send her to the bottom of the sea. The Dorsetshire fired three from close range, and all struck home. Finally, at 10:39am, the Bismarck turned over and sank. To this day it is unclear whether or not she sank because of these torpedoes, or because her crew deliberately flooded her, to keep their ship from falling into British hands.

Men in the water near the bow witnessed one final extraordinary scene. Although Lütjens had been killed by shellfire early in the battle, Captain Lindemann had survived. Now he was sighted with a junior officer, standing near the front of the ship, with seawater fast approaching its sinking bows. From his gestures he appeared to be urging this man to save himself. But the man refused and stayed next to Lindemann. Then, as the deck slowly turned over into the sea, Lindemann stopped and raised his hand to his cap in a final salute, then disappeared. Afterwards, one survivor recalled: “I always thought such things happened only in books, but I saw it with my own eyes.”

By now the Dorsetshire and the destroyer Maori were the only remaining ships at the scene. Close to where the Bismarck had gone down, British sailors could see hundreds of tiny heads floating in the water. Bismarck’s crew had been told that the British shot their prisoners – a sly piece of Nazi propaganda designed to ensure German military forces would always be reluctant to surrender. But as the freezing survivors swam toward the British ships, they discovered this was not the case. Men were hurriedly bundled aboard. But in a cruel twist of fate, a lookout from the Dorsetshire spotted a whiff of smoke a couple of miles away which was thought to be a German U-Boat. The British ships were immediately ordered to move off. Although over a hundred men were rescued, 300 were left in the water. As the day wore on, these exhausted men who had seen their hopes of survival raised then crushed, slowly succumbed to the intense cold of the ocean. Only five lived to tell the tale. Three were picked up by a U-boat, and two by a German weather ship. When other German ships arrived on the scene they found only rubble, lifebelts and a few floating bodies.

Bismarck turned completely upside down on her descent to the ocean floor 5km (3 miles) below, and her four huge gun turrets fell from their housings. By the time she hit the slopes of a vast underwater volcano 20 minutes later, she had righted herself, and set off a huge landslide which carried her further down the slope. There she lies today, where she was recently discovered by the marine archaeologist Robert Ballard. In 1989, his underwater cameras showed that the hull remains intact. Shells, barnacles and sundry other small sea creatures line the wooden planks of the deck. And as the fresh paint applied a few days before she sank gradually dissolved in the seawater, the swastikas on Bismarck’s bow and stern have made a sinister reappearance.