Adolf Eichmann and the Wannsee Conference 1942

Snow fell soft and silent around the shores of Wannsee, cloaking the forest, parkland and elegant villas around the famous lake. Throughout the morning of January 20, 1942, one of the larger villas received a steady stream of chauffeur-driven cars. Arriving at the villa was a succession of 15 of the most senior members of the Nazi government and its elite SS armed forces. As they entered the marble entrance hall, their coats were swept from their shoulders by fawning functionaries, and their arrival was silently noted. Among them were representatives from the Chancellery, the Race and Resettlement Office, the Ministry of Foreign and Eastern Territories, the Justice Ministry, the Gestapo, and the SS. Most had come from nearby Berlin, but some of the army men had been called in from the horror and chaos of the Russian Front, or from other conquered territory in the East. For them, the placid winter scene at Wannsee seemed to belong to some strange parallel universe.

The villa where they assembled, with its marbled staircases and rooms lined with wooden panels, was a substantial three-floored mansion. It had once belonged to a Jewish businessman, but had long since been taken over by the German government. On that January day it was to be the scene of one of the most obscene conferences in human history.

Organizing the preparation of the conference, coordinating the arrival of the delegates, the staff to attend to them, and the buffet prepared for lunch, was Adolf Eichmann. An Austrian Nazi in his late 30s, he was head of the Gestapo’s Jewish affairs section. Eichmann was a curiously quiet and rather anonymous man, once memorably described as looking like a book keeper. He lacked the charisma and spark of some of his more notable colleagues, but he had a reputation for carrying out orders with great thoroughness and efficiency. As the morning progressed, he noted with some satisfaction how well his conference was proceeding.

Last to arrive at Wannsee was Eichmann’s boss, SS General Reinhard Heydrich. As head of the Reich Security Main Office, he was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Europe. Tall, blond and handsome, Heydrich was everything Eichmann was not. A former international-level fencer and naval officer, he looked like the epitome of the “Aryan” (Aryan was the Nazi term for “pure-blooded” Germans) superman – a creature from a Nazi propaganda film. In his most famous photograph, Heydrich stares out with merciless eyes and a cruel mouth. He looks like a stern headmaster about to administer a severe beating to a gaggle of rebellious pupils. No doubt that was the image he wanted to project to the world. In person, the brisk and efficient Heydrich could ooze charm and amiability. But those who crossed him would find themselves subject to chilling threats, made in the casual manner of a Roman emperor, secure in his power of life and death over those around him.

So the conference began. In a haze of cigarette smoke, and the slightly oiled and jovial atmosphere of men who have had a couple of glasses of wine or spirits before lunch, the purpose of the meeting was made plain. Heydrich announced that he had been charged by Hitler’s deputy, Hermann Göring, with “the responsibility for working out the final solution of the Jewish problem” in Nazi territory. The various representatives around him were there to ensure the government cooperated effectively with this venture.

Like all supporters of the Nazis, these distinguished and often highly educated men were broadly sympathetic to Hitler’s corrosive hatred of the Jews. During the nine years of Nazi rule, heightened and reinforced by a constant barrage of anti-Semitic propaganda, they had grown to think of all Jews with repugnance and fear – perhaps as people today would regard a swarm of diseased rats, or a particularly malignant virus.

Nonetheless, what Heydrich had to report was utterly monstrous. So much so, that he still felt the need to couch his words to these hard line Nazis in innocuous phrases, to lessen the impact of what he was saying. He explained to the assembled delegates, with statistics gathered directly by Eichmann, that there was a “storage problem” with the eight million or so Jews in German-held territory. Originally, the Nazis had merely intended to expel them, but the war had closed the borders, making this impossible. Heydrich gradually led his delegates around to the view that the only possible option left to Germany, with regard to the Jews, was “evacuation”. As the conference went on, it slowly dawned on those assembled around the polished oak table what “evacuation” actually meant. What they were talking about was the cold-blooded murder of eight million people – maybe even eleven million, if Germany succeeded in conquering all of Europe.

Of course, there were a few objections. Even among men like these, the idea of murder on this scale was too horrific to contemplate. But eventually, with the odd silky threat here, and a sharp exhortation there, Heydrich gained the approval of all those assembled. Once this “solution” was accepted, the delegates, with their customary efficiency, decided that it would be economic to house the Jews in concentration camps and put them to work on road and factory building projects, where “natural diminution” (that is, death from exhaustion and illness) would gradually reduce their numbers. The old, the sick, and children would not be suitable for such projects, so they would be disposed of as soon as possible.

Since the war began, SS troops in Poland and Russia, known as Einsatzgruppen, or “action squads”, had been systematically shooting Jews in their thousands. But their officers had reported how demoralizing and unpleasant their men had found the job – especially the killing of women and children. So, it was decided the most efficient way to eradicate the Jews that couldn’t be used for work, would be gas. In special death camps, hundreds at a time could be herded into gas chambers disguised as shower rooms, to have the life choked out of them quickly and efficiently. Such chambers could dispose of, say, 600 an hour. Working around the clock, they could “evacuate” thousands of Jews a day. Within a year, if all went to plan, Europe would be Judenfrei, or “Jew free”.

Afterwards, when the delegates had gone, Heydrich, Eichmann, and Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller sat down by the fireplace. They smoked a celebratory cigar and drank a toast to a job well done. According to Eichmann, as the drink flowed they began to sing, and arm in arm they danced a jig around the plush chairs and oak tables of the Wannsee villa.

Four months later, Heydrich was mortally wounded in Prague when he was attacked by two Czech soldiers. He died on June 4. In retaliation, German troops murdered nearly 1,500 Czechs, loosely accused of aiding the assassins. Then, for good measure, they also destroyed the Czech village of Lidice, killing all its male inhabitants, and sending its women and children to concentration camps.

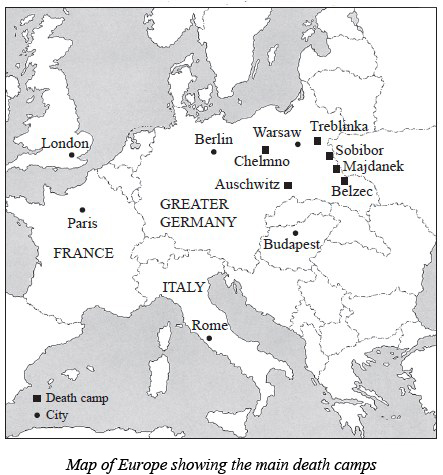

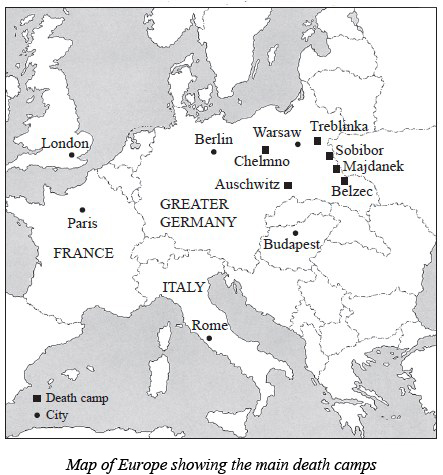

By then, the work agreed at Wannsee had begun. From the Gulf of Finland to the Caucasus mountains, from France’s Atlantic coast to the island of Crete and the North African shores of Libya, in all areas controlled by the Nazis, Jews were gradually rounded up. Some were shot, or gassed in special vans designed for the process. But most were placed on freight trains, packed in their hundreds and thousands into cattle wagons, and transported to death camps – Treblinka, Sobibor, Majdanek, Belzec, Chelmno and Auschwitz – names which would haunt the lives of an entire post-war generation.