When Odysseus and his companions returned to Circe’s island it was still night, and so after they ran their ship ashore they ‘stepped out onto the break of the sea beach, and there we fell asleep and waited for the divine Dawn’. At daybreak Odysseus sent his companions to Circe’s house to bring back the body of Elpenor, which, as he wished, they cremated and covered with a tumulus, and afterwards they ‘planted the well-shaped oar in the very top of the grave mound’.

While they were busy at their work Circe arrived with her attendants, who were carrying bread and meat and wine for Odysseus and his companions. Odysseus says that ‘Bright among goddesses she stood in our midst and addressed us’:

Unhappy men, who went alive to the house of Hades,

so dying twice, when all the rest of mankind die only

once, come then eat what is there, and drink your wine, staying

here all the rest of the day, and then tomorrow, when dawn shows,

you shall sail, and I will show you the way and make plain

all details, so neither by land nor on the salt water

you may suffer and come to grief by unhappy bad designing.

They then sat there feasting on meat and wine, and at sunset the men lay down to sleep, while Circe took Odysseus by the hand and led him away from his companions, so that she could tell him of the dangers he would encounter on his homeward voyage, beginning with the Sirens.

You will come first of all to the Sirens, who are enchanters

of all mankind, and whoever comes their way; and that man

who unsuspecting approaches them, and listens to the Sirens

singing, has no prospect of coming home and delighting

his wife and little children as they stood about him in greeting.

But the Sirens by the melody of their singing enchant him.

They sit in their meadow, but the beach beside it is piled with boneheaps

of men now rotted away, and the skins shriveled upon them.

Circe then told Odysseus what he and his companions must do to make their way safely past the deadly lure of the Sirens.

You must drive straight on past, but melt down sweet wax of honey

and with it stop your companion’s ears, so none can listen;

the rest, that is, but if you yourself are wanting to hear them,

then have them tie you hand and foot on the fast ship, standing

upright against the mast with the rope’s ends lashed around it,

so that you can have joy in hearing the song of the Sirens;

but if you supplicate your men and implore them to set you

free, then they must tie you fast with even more lashings.

According to one version of the myth, the Sirens, known in Greek as Seirenes, were daughters of the river god Achelous and the muse Melpome. They were originally handmaidens of Persephone, daughter of Demeter. When Persephone was secretly kidnapped by Hades and taken to the Underworld, Demeter gave them the bodies of birds and sent them to the netherworld of Hades to help in the search for her daughter.

Some ancient writers, including Strabo, say that the Sirens were fated to live only till some mariner hearing their song would pass without being enchanted, as did Odysseus, and thereupon they plunged into the sea and were transformed into rocks. Strabo writes:

Surrentum [Sorrento], a city of the Kampanoi [Campania], whence the Athenaion juts forth into the sea, which some call the Cape of Seirenoussai … It is only a short voyage from here to the island of Kaprea [Capri]; and after doubling the cape you come to desert, rocky isles, which are called the Seirenes [Sirens].

Ernle Bradford notes that the rocky isles mentioned by Strabo ‘should be identified with the Galli islets, which lie at the entrance to the Gulf of Salerno’. He goes on to write that ‘It is about seventy-five miles from Cape Circeo to the Galli if one sails direct through the Procid and Capri channels; a little more if, as Ulysses probably did, one follows the coast along the Bay of Gaeta and round the Bay of Naples.’

When we first explored this surpassingly beautiful coast, early in the summer of 1963, I had in hand as a companion-guide Siren Land (1911) by Norman Douglas, who spent most of his adult life in and around the Bay of Naples, particularly on the Isle of Capri, where he died in 1952. More than any writer, ancient or modern, he evokes the enchanting atmosphere of Siren Land, which he describes from the uplands of Sorrento:

The eye looks down upon the two gulfs of Naples and Salerno, divided by a hilly ridge; the precipitous mass of Sant’ Angelo, stretching right across the peninsula in an easternly direction, shuts off the view from the world beyond. This is Siren Land. To the south lies the islets of the Sirens, nowadays known as the Galli; westwards, Capri, appropriately associated with them from its craggy and yet alluring aspect; Sorrento, whose name has been derived from them … lies on the northern slope. A favoured land, flowing with milk and honey; particularly the former; Saint Noj maintains as proof of its fertility the fact that you can engage wet-nurses there from the ages of fourteen to fifty-five.

After Circe told Odysseus how to escape the Sirens, she instructed him on what he should do to pass between the clashing rocks known as the Rovers, saying that the only ship ever to survive the passage was the famous Argo, carrying Jason and the Argonauts after their visit to Circe’s brother Aietes:

No ship of men that came here ever has fled through,

but the waves of the sea and storms of ravening fire carry

away together the ship’s timbers and the men’s bodies.

That way the only seagoing ship to get through was Argo,

who is in all men’s minds, on her way home from Aietes;

and even she would have been driven on the great rocks that time,

but Hera saw her through, out of her great love for Jason.

Circe tells Odysseus that the passage is made even more perilous because of the two monstrous sea-goddesses Scylla and Charybdis who dwelt on the Rovers, one on either side. She says that Scylla lives in a cave halfway up the higher rock, and that no one, ‘not even a god encountering her could be glad at that sight’:

She has twelve feet, and all of them wave in the air. She has six

necks upon her, grown to great length, and upon each neck

there is a horrible head, with teeth in it, set in three rows

close together and stiff, full of black death. Her body

from the waist down is holed up inside the hollow cavern,

but she holds her heads poked out and away from the terrible hollow

and there she fishes, peering all over the cliffside, looking

for dolphins or dogfish to catch or anything bigger,

some sea monster of whom Amphitrite keeps so many;

never can sailors boast aloud that their ship has passed her

without any loss of men, for with each of her heads she snatches

one man away and carries him off from the dark-prowed vessel.

Circe then tells Odysseus that Charybdis lives on the smaller of the two rocks, which lie so close together that ‘you could even cast with an arrow/across’:

There is a great fig tree grows there, dense with foliage.

And under this shining Charybdis sucks down the black water.

For three times a day, she flows it up, and three times she sucks it

terribly down; may you not be there when she sucks down water,

for not even the Earth-Shaker could rescue you out of that evil.

But sailing your ship swiftly drive her past and avoid her,

and for Scylla’s rock instead, for it is far better

to mourn six friends out of your ship than the whole company.

All ancient sources and most modern writers, including Ernle Bradford, put the rocks of Scylla and Charybdis as the northern end of the Strait of Messina, with Scylla on the toe of Italy and Charybdis at the north-eastern tip of Sicily, separated by about six kilometres, which Homer has narrowed to a bowshot.

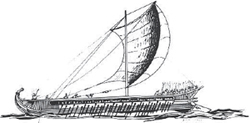

Thus when Odysseus left Circe’s isle with his companions he would have sailed by the Bay of Naples and down the Italian coast, passing just to the east of the volcanic isle of Stromboli and the Lipari Islands as he approached the Strait of Messina.

We passed through the Strait of Messina in June 1963 aboard an Italian passenger ship, bound for Naples, emerging into the Tyrrhenian Sea just before sunset. A couple of hours later we passed to the east of Stromboli, whose volcano was glowing in the darkness. And so once again I crossed the wake of Odysseus, this time going in the opposite direction.

Thucydides writes:

The Strait in question is the sea that lies between Rhegium [Reggio] and Messana [Messina], the place where Sicily is the least distance from the Continent, and this is the so-called Charybdis through which Odysseus is said to have sailed. It has naturally become accounted dangerous because of the narrowness and of the currents caused by the inrush of the Tyrrhhenian Sea.

Ernle Bradford quotes the Admiralty Pilot regarding the tidal currents and whirlpools in the Strait of Messina, one of the few places in the Mediterranean, the Euboea Channel being another, where such phenomena are observed.

Twice each lunar day the water level has a maximum slope northward through the strait, and twice each lunar day a slope southward. Though the difference of level is small, amounting to less than a foot at springs, it is concentrated into such a short distance that streams with a rate of four knots at springs are generated by it. These springs run with their greatest force where the strait is narrowest and shallowest, viz. between Punta Pezzo and Ganzirri.

Punta Pezzo is on the Italian side of the strait close to the Rock of Scylla, where the village of Scilla bears its name, while the Sicilian village of Ganzirri is three kilometres along the strait from Cape Pesaro, the Rock of Charybdis, where, some two or three hundred metres offshore, there is a powerful whirlpool associated with her name. The Admiralty Pilot notes that this whirlpool

is the Charybdis of the ancients; its opposite number Scylla is now very feeble due to changes in the local topography caused by an earthquake in February 1783. There is, however, every reason to suppose that a whirlpool did exist off the town of Scilla and that both it and Charybdis were rather more impressive than they are today.

Circe’s remark that Scylla, looking out from her seaside cavern, fishing for dolphins or dogfish or any bigger sea monster, prompted Ernle Bradford to note that this part of the strait ‘is also remarkable for its variety of unusual marine creatures, dogfish, octopus, and squid among others’. He quotes from an article by the American biologist Dr Paul A. Zahn in The National Geographic Magazine (November 1953), entitled ‘Fishing in the Whirlpool of Charybdis’. Because of the topography of the seabed, according to Zahn, during the spring tides,

the surface waters in the Strait of Messina abound with living or half-living creatures whose habitat is normally down where all is black and still … After a strong onshore wind I have often seen beaches along the Strait of Messina littered with thousands of dead or dying creatures whose strange appearance would make even the artist Dali wince.

After Circe advised Odysseus on how to get past Scylla and Charybdis, she told him what to do when he reached the island of Thrinikia, home of the sun-god Helios. She repeated the advice of Teiresias concerning the cattle of Helios:

Then, if you keep your mind on homecoming and leave these unharmed,

you might all make your way to Ithaka, after much suffering;

but if you do harm them, then I testify to the destruction

of your ship and your companions, but if you yourself get clear,

you will come home in bad case with the loss of all your companions.

At the break of day, when Circe had completed her instructions, she returned to her palace, while Odysseus went back and told his companions to board their ship. He says that Circe had sent them a following breeze, and so they ‘let the wind and the steersman hold her steady’. He then told his companions about the instructions that Circe had given him to avoid the perils awaiting them, beginning with the Sirens.

While he was speaking the ship was approaching the Sirens’ isle, when suddenly the wind dropped, ‘and some divinity stilled the tossing/waters’.

The crew took down the sails and stowed them away, while Odysseus took a piece of wax and stopped up their ears, ‘and they then bound me hand and foot in the fast ship, standing/upright against the mast with the ropes’ ends lashed around it,/and sitting then to row they dashed their oars in the gray sea’. When they came within earshot of the island their ship ‘was seen by the Sirens, and they directed their sweet song toward us’:

Come this way, honored Odysseus, great glory of the Achaians,

and stay your ship, so you can listen here to our singing;

for no one else has ever sailed past this place in his black ship

until he has listened to the honey-sweet voice that issues

from our lips, then goes on, well pleased, knowing more than ever

he did, for we know everything the Argives and Trojans

did and suffered in wide Troy through the gods’ despite.

Over all the generous earth we know everything that happens.

Odysseus was sorely tempted by the song of the Sirens, but though he indicated to his companions that he wanted to be freed they tied him to the mast even more securely and rowed on until they were well beyond the island:

So they sang, in sweet utterance, and the heart within me

desired to listen, and I signaled my companions to set me

free, nodding with my brows, but they leaned on and rowed hard,

and Perimedes and Eurylochos, rising up straightaway,

fastened me with even more lashings and squeezed me tighter.

But when they had rowed on past the Sirens, and we could no longer

hear their voices and lost the sound of their singing, presently

my eager companions took away from their ears the beeswax

with which I had stopped them. Then they set me free from my lashings.

Heading south, their next landmark was the volcanic isle of Stromboli, which they passed to their west as they approached the Strait of Messina:

But after we had left the island behind, the next thing

we saw was smoke, and a heavy surf, and we heard it thundering.

The men were terrified, and they let the oars fall out of

their hands, and these banged all about in the wash. The ship stopped

still, with the men no longer rowing to keep her on her way.

Odysseus walked fore and aft in the ship, calming his companions and telling them to row on, ordering the steersman to stay clear of the volcanic isle and stay on course for the strait between Scylla and Charybdis.

Odysseus says that ‘I put on my glorious armor and, taking up two long/spears in my hands, I stood bestriding the vessel’s foredeck/at the prow, for I expected Skylla of the rocks to appear first/from that direction, she who brought pain to my companions.’ And thus they made their way up the strait, with Scylla menacing to the east and Charybdis to the west.

So we sailed up the narrow strait lamenting. On one side

was Skylla, and on the other side was shining Charybdis,

who made her terrible ebb and flow of the sea’s water.

When she vomited it up, like a caldron over a strong fire,

the whole sea would boil up in turbulence, and the foam flying

spattered the pinnacles of the rock in either direction;

but when in turn she sucked down the sea’s salt water,

groaned terribly, and the ground showed at the sea’s bottom,

black with sand; and green fear seized upon my companions.

Odysseus goes on to say that while they were looking to avoid being swallowed up by the sea monster on one side, the one on the other side struck without warning.

We in fear of destruction on one side kept our eye on Charybdis,

but meanwhile Skylla out of the hollow vessel snatched six

of my companions, the best of them for strength and hands’ work,

and when I turned to look at the ship, with my other companions,

I saw their feet and hands from below, already lifted

high above me, and they cried out to me and called me

by name, the last time they ever did it, in heart’s sorrow.

Circe had told Odysseus that when he got past Scylla and Charybdis he would come to the isle of Thrinikia, where the sun-god Helios, also known as Hyperion, kept his inviolable cattle. Writers both ancient and modern put Thrinikia off the east coast of Sicily. Ernle Bradford identifies it as Rada di Taormina, a cove off the ancient town of Taormina, 42 kilometres south of Scylla and Charybdis along the Strait of Messina.

Odysseus says that after he and his surviving companions escaped from the dread sea monsters they made their way to the island of Helios.

While I was on the black ship, still out on the open water,

I heard the lowing of the cattle as they were driven

home, and the bleating of sheep, and my mind was struck by the saying

of the blind prophet, Teiresias the Theban, and also

Aiaian Circe. Both had told me many times over

to avoid the island of Helios who brings joy to mortals.

He then passed on these warnings to his companions, saying ‘So drive the black ship onward and pass the island.’ But Eurylochos objected, saying that they were all worn out and hungry, and should stop on the island and ‘make ready our evening meal, remaining close by our fast ship,/and at dawn we will go aboard and put forth into the wide sea’.

The other men agreed with Eurylochos, and so Odysseus reluctantly gave in, but he made them swear an oath that they would not touch the cattle of the sun-god, but would eat ‘at your pleasure of the food immortal Circe provided’. They all agreed, but during the night a fierce storm arose from the south, preventing them from leaving the next morning, and so they berthed their ship, ‘dragging her into a hollow sea cave/where the nymphs had their beautiful dancing places and sessions’.

But for the next month the winds blew only from the south and east, and since they needed a west wind for their homeward voyage they had to remain on the island. When their supplies ran out ‘they turned to hunting, forced to it, and went ranging/after fish and birds, anything they could lay hands on,/and with curved hooks, for the hunger was exhausting their stomachs’.

Odysseus went off by himself to pray to the gods, ‘but what they did was to shed a sweet sleep on my eyelids,/and Eurylochos put an evil counsel before my companions’. Eurylochos persuaded his companions, rather than starve to death, to kill the cattle of Helios and sacrifice them to the gods. ‘But if, in anger over his high-horned cattle,/he wishes to wreck our ship, and the rest of the gods stand by him,/I would far rather gulp the waves and lose my life in them/once for all, than be pinched to death on this desolate island.’

Odysseus says that when he awakened and headed back to the ship, ‘the pleasant savor of cooking meat came drifting around me’, and he cried out in grief: ‘Father Zeus, and you other everlasting and blessed/gods, with a pitiless sleep you lulled me, to my confusion,/and my companions staying here dared a deed that was monstrous.’

The nymph Lampetia, daughter of the sun-god, ran swiftly to tell her father that Odysseus and his companions had killed his sacred cattle. Helios then demanded that Zeus punish them, saying that unless they ‘are made to give me just recompense for my cattle,/I will go down to Hades and give my light to the dead men’.

Zeus said in answer: ‘Helios, shine on as you do, among the immortals/and mortal men, all over the grain-giving earth. For my part/I will strike these men’s fast ship midway on the open/wine-blue sea with a shining bolt and dash it to pieces.’

Odysseus goes on to say that for the next six days his companions feasted on the cattle of the sun, and then on the seventh day, the south wind finally stopped blowing, ‘and presently we went aboard and put forth on the wide sea,/and set the mast upright and hoisted the white sails on it’.

After they left Thrinikia the sky darkened and suddenly a screaming west wind came upon them and snapped the mast, which struck the steersman on the head and killed him.

Zeus with thunder and lightning together crashed on our vessel,

and, struck by the thunderbolt of Zeus, she spun in a circle,

and all was full of brimstones. My men were thrown in the water,

and bobbing like sea crows they were washed away on the running

waves all around the black ship, and the god took away their homecoming.

Odysseus tells of how he survived by lashing together fragments of the broken ship to fashion a raft on which he floated before the howling wind:

But I went on my way through the vessel, to where the high seas

had worked the keel free out of the hull, and the bare keel floated

on the swell, which had broken the mast off at the keel; yet

still there was a backstay made out of oxhide fastened

to it. With this I lashed together both keel and mast, then

rode the two of them, while the deadly stormwind carried me.

The wind then changed direction and began blowing from the south, carrying him back up the Strait of Messina, to Scylla and Charybdis. As his raft was sucked down by the whirlpool under Charybdis, he reached up to grab a fig tree on the rock, holding on to it until the water surged upward, and then he dropped down next to his raft and clambered aboard, paddling away with both hands.

Odysseus now concludes his long recital to King Alkinoös and his court, telling them of how, after his second escape from Scylla and Charybdis, he drifted in his raft until he came to Calypso’s isle.

From there I was carried along nine days, and on the tenth night

The gods brought me to the island Ogygia, home of Kalypso

with the lovely hair, dreaded goddess who talks with mortals.

She befriended me and took care of me. Why tell the rest of

this story again, since yesterday in your house I told it

to you and your majestic wife? It is hateful to me

to tell a story over again, when it has been well told.

Calypso’s isle has been identified with a number of places, but the most plausible one is Gozo, the second largest island in the Malta archipelago. A bay on the north coast of the island named Ir-Ramla has long been pointed out as the place where Odysseus landed, and a cavern above the sea there is called Calypso’s Cave. Ernle Bradford, who for years lived in Malta, identified this as the place where Odysseus landed, based on the winds and currents of the seaways around Sicily, which he had sailed in both war and peace.

A guidebook to Malta published in 1910, with text by Frederick W. Ryan and paintings by the nineteenth-century Maltese artist Vittorio Boron identifies the cavern at Ramla Bay as Calypso’s Cave, where Odysseus was to spend seven long years with the nymph before he was allowed to begin the penultimate stage of his homeward journey. As Ryan writes of Calypso’s Cave:

The annalists of the islands have always claimed Gozo as the Ogygia of Homer, where dwelt Calypso when she allured Ulysses. By this statement, no doubt, they wished to secure, like historians of the Middle Ages everywhere, a good place for their own particular country in the geography – whether real or imaginary – of the classic; and in this way, indeed, the fair Calypso has had quite twenty island homes placed at her disposal. Anyway, we find Gozo called by the Maltese the Island of Calypso, and her Grotto may there be admired today by the uncritical.