AS WITH MOST OTHER ELEMENTS of China’s ongoing military modernization, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has exploited foreign technology to achieve rapid capability enhancement, both by outright weapon systems purchase and by acquiring select foreign technologies to improve its capacity to build modern indigenous submarines and supporting surface combatants. The PLAN has demonstrated its capacity for copying Russian submarine designs, for incorporating Russian and European technology into recent designs, and for building new designs based largely on Russian technology.1 Since the early 1990s, China has embarked on a new stage of gathering foreign inputs. These include Russian Kilo conventional attack submarines (SSKs) and their modern weapons, as well as Russian nuclear submarine technology and design expertise. In addition, Russian technology is also facilitating a “revolutionary” advance in PLAN nuclear attack and ballistic-missile submarines. Russian surface combatants, naval weapons, and naval aircraft are enabling the PLAN to better support its submarines and defend against an adversary’s air and naval forces. The PLAN is also interested in acquiring greater European submarine and naval combatant technologies, a prospect that will grow should the European Union lift its 1989 arms embargo.

China is developing a large and modern fleet of nuclear- and conventional-powered submarines as part of a more comprehensive military modernization designed to advance strategic goals in Asia and beyond.2 While new conventional and nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs) are viewed as anti-carrier/surface combatant platforms, for potential conflicts over Taiwan crises or maritime resources, both China’s increasingly global interests and emerging technology may push th e PLAN into more complex submarine missions. The advent of China’s second generation SSBN may lead to the dedication of more attack submarines to Gorshkov-style “bastion” missions, while the development of land attack cruise missiles and aircraft carriers for the PLAN could see Beijing’s SSNs devoted to future power-projection missions. Such factors might lead China’s leadership to support construction of more and better submarines.

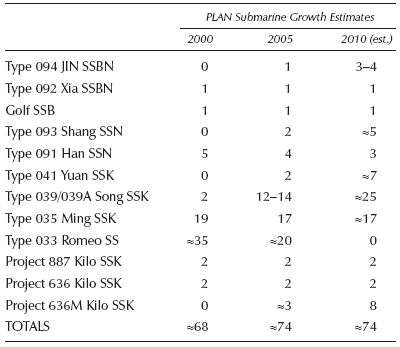

In late July 2005, retired U.S. Adm. Al Konetzni stated that by 2020 the PLAN could have twice the number of submarines as the U.S. Navy, and three times by 2025.3 Konetzni’s reported comments did not explain his estimates, but they certainly reflect planned U.S. SSN inventory reduction.4 Unfortunately, China does not publish any open official data that might allow confirmation of its submarine modernization or construction plans. Nevertheless, reasonable estimates can be made from a variety of open sources, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1 projects that the PLAN submarine inventory will remain nearly constant, at approximately seventy vessels until 2010. It is important to note, however, that during that period the number of modern, capable submarines will sharply increase, from six in 2000 to an estimated forty in 2010. This percentage of modern vessels will be less if series production of the Yuan-, Shang-, and Jin-class submarines become delayed by development obstacles. On the other hand, it may underestimate both the size and capability of the order of battle if accelerated indigenous submarine production is matched by additional orders for Russian submarines. Estimates of PLAN submarine forces beyond 2010 are especially speculative. Several factors, nonetheless, affect the direction and rate of that growth.

Table 1. Estimated Chinese Submarine Order of Battle

Note: Table derived from: Jane’s Fighting Ships; International Institute for Strategic Studies; www.sinodefense.com; press reports; author interview data. Numbers count launched not commissioned submarines. Kilo numbers for ships already in China. Song projection assumes two–three annual production. 2010 estimates are author speculation. Chart is intended to be illustrative, not definitive.

One critical factor affecting PLA submarine investment is the desire to build a modern fleet. It appears that the Type 093 Shang SSN will complement the existing four Type 091 Han SSNs. But Han force levels are likely to reduce to three—the number of vessels that received midlife upgrades between 1998 and 2002. Should the PLA opt for multiple squadrons of SSNs, it could continue to replace Hans with 093s, or perhaps even introduce a more advanced SSN design early in the next decade. Similarly, it is possible that 1960s vintage Type 033 Romeo submarines are being rapidly replaced by Kilo, Song, and Yuan SSKs. Type 035 Mings built in the 1980s and 1990s still have years of useful life and may be assigned to reserve units for coastal defense, barrier patrol, mining or training missions. Key factors affecting force levels include further Kilo or Lada/Amur purchases from Russia. Also unknown is whether Song and Yuan production will continue simultaneously, or if advanced versions of the latter will, perhaps with air-independent propulsion (AIP), succeed the Song.

Another factor affecting submarine force levels might come from a Chinese leadership decision to invest a substantial proportion of its nuclear missile forces in SSBNs, and whether the PLAN would then be charged with building Soviet-style SSBN bastions. Former PLAN chief and Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) Admiral Liu Huaqing, who studied in the Soviet Union, has been noted for his admiration of Gorshkov, and his bastion strategy.5 The Bohai Gulf could become one such bastion. Supporting this possibility is a report of an “underwater” submarine base under construction in Huludao.6 The JL-2 SLBM’s estimated 5,400NM range would allow for substantial coverage of the continental United States and all of India from these waters.7

The Bohai Gulf has an average depth of approximately one hundred fifty feet, which would make interdiction by U.S. SSNs difficult, but the PLAN cannot ignore the possibility that U.S. unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) could turn the constricted gulf into an SSBN trap.8 In addition, a potential deepening of U.S.-Japanese missile defense cooperation might allow eventual boost-phase targeting of Bohai-launched SLBMs.9 As such, it is possible that the PLAN is preparing for access to safer deep-water patrol areas for its SSBNs. This could explain why the PLAN is building a nuclear submarine facility due East of Yulin Base on Hainan Island.10 One Asian military source expects this base to become operational in 2006.11 Located on Hainan’s south coast, this base will afford access to deeper patrol areas in the South China Sea, but PLAN SSBNs may have to sail between Taiwan and the Philippines to reach launch areas that would allow JL-2 SLBMs to reach the United States. Such a requirement could strengthen PLA determination to conquer Taiwan, since Hualien and Su Ao, for example, have immediate access to deep water patrol areas.12 Such a dispersal of SSBN operating areas could be accompanied by an increase in PLAN SSNs in anticipation of potential United States, Japanese, and Indian ASW opposition. The PLA might also invest in more long-range-bomber, surface-ship, and even aircraft-carrier elements consistent with a Soviet-style bastion strategy.

Both SSN and SSBN numbers could increase should the PLAN be given counter-SSBN and space-related defensive missions. There has been some debate within the PLA over which service should control military space,13 with recent reporting suggesting the future formation of a new and independent Space Force subordinate to the CMC.14 Inasmuch as the DF-21 and -31 land-based missiles are being modified for mobile space-launch vehicles (SLVs)15 that could carry future antisatellite payloads, it is possible that PLAN SSBNs could also be configured for space warfare missions. Since the JL-2 is said to be based on the DF-31, it may be large enough to boost payloads into low earth orbit if launched near or south of Hainan Island’s 20° latitude. In early 2004 one Dalian Naval Academy author noted, “By deploying just a few antisatellite nuclear submarines in the ocean, one can seriously threaten the entire military space system of the enemy. In addition to antisatellite operations, these nuclear submarines can also be used for launching low-orbit tactical micro-satellites to serve as powerful real-time battlefield intelligence support.”16

As compared with previous decades, new technologies offer enhanced capabilities, which in turn could also justify fewer submarines. For example, it is not likely that production for the new Song or Yuan classes will match the 80–160 of the now-ancient Romeo. But technology may also justify larger numbers (e.g., with SSNs). For example, Asian sources note that China is developing two families of long-range land attack cruise missiles (LACMs), one for the 2nd Artillery, and another that will be used by the PLA Air Force and the PLAN.17 These, plus the expected deployment by 2005 of a new constellation of PLA navigation, data-relay, and radar and electro-optical surveillance satellites,18 could turn the new generation of PLA LACMs into a global power-projection tool—if deployed by sufficient numbers of Type 093 SSNs. The production of further Shang or successor SSNs would allow China’s leadership to intervene abroad to defend economic and political interests. A Chinese decision to build aircraft carriers might also serve to justify the construction of larger numbers of SSNs.19

The modernization and possible expansion of the PLAN submarine fleet will also require improvements to the PLAN’s logistics, training, and submarine design/production capabilities. While open reporting on these subjects is not extensive, there is some evidence the PLAN understands these requirements. Asian sources, including one from the PLA, have noted that the PLAN intends to build or expand five submarine bases.20 The recent acquisition of eight new Kilo submarines suggests that the PLAN has overcome its publicized training shortfall for these new vessels. It is significant that in 2004 Song production was expanded to a second shipyard in Shanghai, which may indicate that SSK production capacity has doubled. It is probable that improved design and production techniques and technologies have also been passed to the submarine sector from China’s burgeoning, modernizing commercial shipyards. This would help to explain the dramatic improvements of the Song and Yuan over previous submarine classes. Modern modular construction techniques, suggested in ample Internet photos of Song-class submarines in Shanghai, were also likely facilitated by the absorption of advanced Western computer-aided design technologies.21 Modular techniques are very likely also used in the construction of Yuan SSK and Type 093 and 094 nuclear submarines.22

PLAN leaders have always relied on foreign technology and have placed a high priority on purchasing needed submarine systems. In coordination with various PLA and PRC state intelligence services, China has also placed a consistent high priority on exploiting all manner of open-source information on submarines from North America, Europe, Israel, and Russia.23 China also relies on espionage to gather information on all submarines, with recent incidents reported in Japan,24 and one in which Russia stopped China from buying some derelict subs from its Pacific Fleet.25 In addition, on October 28, 2005, U.S. authorities arrested four ethnic Chinese accused of compromising sensitive information concerning quiet electric drive technology for U.S. ships and submarines, electronic defenses for U.S. aircraft carriers, and electromagnetic pulse weapons.26

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation emerged as the PLAN’s most important source of both conventional and nuclear submarine technology. For both Russia and China, the submarine technology relationship is perhaps one of the most important, if lesser known, dimensions of their growing bilateral “strategic partnership.” For Russia the commercial aspects are critical as submarine and related technology sales support domestic design and production capacity. In 2005, Russian naval weapons exports were projected to eclipse previously dominant aviation exports, comprising roughly $3 billion out of $5 billion in anticipated exports. Of the $3 billion in naval exports, half are expected to comprise submarines and related products, for which the PLAN is the largest customer.27

While Russian Kilo SSK sales are visible manifestations of this relationship, much less is known about the degree and depth of Sino-Russian cooperation in SSN and SSBN design and construction. Since the mid-1990s there have been reports about Russian assistance to China’s Type 093 SSN and 094 SSBN. In 1997 Jane’s reported that Russia’s Rubin submarine-design bureau began assisting China’s SSN development in 1995.28 In 1997 the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) estimated that the 093 would be similar in capability to the Soviet Victor III SSN,29 the last of which entered the Russian navy in 1992. Furthermore, in 2003 the Pentagon stated, “The Type 093-class will compare to the technology of the Russian Victor III SSN and will carry wire-guided and wake-homing torpedoes, as well as cruise missiles.”30 What is not clear from these sources is whether Russia is providing the PLA with Victor III (Project 671)– or the advanced Victor III (Project 671RTM)–level technology. In 2004 ONI reported that the Type 094 “benefits from substantial Russian technical assistance,”31 but did not elaborate. In 2003 the CIA noted in a report to Congress, “Russia continued to be the main supplier of technology and equipment to India’s and China’s naval nuclear propulsion programs.”32

One might therefore assume that not only Rubin, but also a larger swath of Russia’s submarine sector, is interacting with China. Rubin was not the lead bureau for Russia’s second–third generation Project 671RTM Victor III, but it is the lead bureau for the design of the next fourth generation SSBN, Russia’s Project 955 Borei.33 If indeed Rubin is currently the main interlocutor with China’s SSN/SSBN design sector, it may be possible that Russian SSBN-related systems have been adopted for both Type 093 and 094. Other possibilities include either direct Chinese interaction with the Malachite Bureau, which is now leading the design of the fourth generation Project 885 Yasen/Severodvinsk SSN,34 and was also involved in the Project 671 family, or potentially subcontracting elements of this bureau to Rubin to assist Chinese SSN development.

While producing an SSN with the capabilities of the Project 671RTM would represent a remarkable advance for the PLAN, it might also be expected that China would press hard for Russia’s latest fourth generation SSN and SSBN technologies, and use its clout as Russia’s largest military customer to secure them. It is curious that the latest ONI artist projection for the Type 094, and most drawings and models of the Project 955, show both carrying twelve SLBMs in slightly separated groups of six.35 However, this projection is contradicted by what appeared to be the first Chinese Internet source photo of the Type 094 that emerged in mid-2006. If legitimate, this photo suggests the new Chinese SSBN to be more of an evolution from the Type 092, lacking even the acoustic advantages of a smooth hull.

This, however, does not dismiss the possibility that some Russian fourth-generation submarine technologies may have been sold to support this program. Russia previously sought to limit the sophistication of military technology sold to China, and there are powerful incentives for Russia to keep China just below its future submarine capabilities. But such restrictions have eroded in recent years as Russia has sought to boost sales and to ward off potential European competition.36 Russian weapons manufacturers’ faith in being able to make the next generation system apparently serves to justify their willingness to sell very capable current generation systems.37

Over the last decade, Russia has promoted progressively advanced SSKs and related technology for sale to China. In 1993 the PLA ordered four Kilo conventional submarines—two Project 877EKMs and two Project 636s—all delivered by 1999. In 2003 the PLA ordered eight more improved 636M SSKs, to be delivered by 2006 or 2007. These are the most advanced Kilos in any navy and their sale made China the largest foreign Kilo customer. In late 2003 there were reports that Russia was considering allowing Chinese co-production of its submarines in order to preempt possible European submarine exports.38 More recently there have been suggestions of Chinese interest in the latest Project 677 Lada SSK39 (also known by the export designation Amur), the first of which was launched in April 2004. There have been periodic suggestions, especially in the Russian press, of Chinese interest in buying advanced Project 971 Akula SSNs and Project 949 Oscar-class nuclear-powered cruise missile submarines (SSGNs).40 China may well decline to match India’s potential purchase of one or more Akulas, and instead absorb as much Russian technology as possible to further its own advanced nuclear submarines. The fact that China has not opted for Russian Akulas may also mean that it is pleased with the Russian components that may be making the Type 093 and 094 into formidable submarines.

There is some evidence that China is perhaps moving to adopt a critical Russian practice: design competition. The Yuan’s Russian-style attributes may emphasize combat survivability, which contrasts to some degree with the design of the Song SSK. This suggests the possibility that China may be adopting some degree of design competition. Movement in this direction would be consistent with the PLA’s General Armament Department and logistic reforms of 1998, but there was little such evidence in the submarine sector until the Yuan’s emergence. Russia, however, has ample experience with sustaining multiple design bureaus for the purpose of obtaining better designs through competition. If China moves to adopt similar design competition, one might expect greater innovation its submarine designs and related technologies.

Since the mid-1990s China has pressured Russia to reduce its sales of weapons systems in favor of increased components and technology. This trend is visible concerning air force weapons and surface warships, and likely is true for submarines as well.41 Regarding SSKs, there are enough outward similarities between the 677 Lada and the PLAN’s new Yuan to suggest it has benefited from some level of Russian technology transfer. Russia would have much to offer, as the Chinese are well aware from their experience with the Kilo. It is likely that China has been well briefed on the new engine, quieting, anechoic tiling, automation, and combat control systems developed for the Lada. Russia has also been developing fuel-cell- and chemical-based AIP systems, and has offered them for sale or for refitting to Kilo SSKs.42

China would have an interest in practically all nuclear-related submarine technologies that Russia would have to offer, regardless of whether they were made available. There is one report that China obtained sophisticated automatic welding technology, potentially from Russia,43 which is critical for submarine hull construction. China would also be interested in Russian advances in submarine metal and material technology. China would have particular interest in the newer Russian OK-650 series nuclear reactors, which use natural cooling circulation at low speeds to remove radiated noise from cooling pumps. China would also be interested in all manner of passive and active Russian noise-reduction technologies, from advanced anechoic tiles, to platform and machinery isolation, to hull-flow dynamics, and active noise-canceling systems. Inasmuch as India manufactures Russian-designed anechoic tiles for its Kilo submarines, it is reasonable to assume this technology has also been transferred to China. In addition, China would also seek the latest Russian submarine sonar systems, both fixed and towed arrays, and advanced computer programs to process data. Russian advances in non-acoustic detection technologies that measure wake and radiation parameters would also be of interest to China.

With the acquisition of Kilos, Sovremenny DDGs, and Kamov Ka-28 ASW helicopters, the PLAN has also had access to a wide array of submarine and antisubmarine weapons. It can be assumed that with the Kilo the PLAN also acquired a package of modern Russian wire-guided and wake-homing torpedoes, mobile mines, torpedo decoys, and perhaps even antitorpedoes. China has also reporedly purchased the VA-111 Skhvale-E rocket-powered supercavitating torpedo.44 However, it is not clear that it is being used as a weapon, while other sources have noted that the PLA seeks to develop indigenous supercavitating weapons.45 In 2004 it is likely the PLAN also contracted to purchase the entire Novator Klub-S system of antiship, land-attack, and antisubmarine torpedo-carrying missiles.46

In the late 1990s there were reports that the PLAN’s early difficulties with its new Kilos resulted from failure to purchase adequate crew training from Russia. In recent years there has been no open commentary pointing to persistence of this problem. In 2005, however, Russian submarine exports to China entered a new phase, the transfer of doctrine and tactics, or “software.” Submarines from both countries participated in blockade, antiship, and antisubmarine warfare exercises as part of the August 18–25 “Peace Mission 2005” combined arms exercises. This is most likely the first time that PLAN submarines have ever exercised with naval forces, much less other submarines, from a peer-level power.

This new phase holds the potential to accelerate improvement of PLAN submarine operations, particularly as subsequent bilateral exercises increase in size and sophistication. Since the 1960s, the Soviet navy has sought to perfect the coordination of naval missile strikes from submarine, ship, and air platforms, and even by ballistic missiles. This was a tremendous effort for the former Soviet Union, prompting advances in multiple weapons platforms, space surveillance, satellite communication, and command and control. Despite its current financial distress, the Russian navy retains smaller numbers of modernized SSNs, SSGNs, Tu-22M3 Backfire and Tu-142 Bear bombers, and even one aircraft carrier, to sustain its missile-strike-based doctrine. As the PLA purchases more of these systems, and Moscow continues to view large-scale military exercises as strategically and commercially advantageous, the PLAN may gain experience with advanced Russian naval doctrine and tactics.

Substantial European submarine or related technology sales may become an option for the PLAN after the European Union ends its 1989 post-Tiananmen arms embargo. As the EU started to do so in late 2003, the Bush administration began an intense political campaign to block the initiative, and achieved such a stay by May 2005. However, the principle proponents of lifting the embargo, France and Germany, may revive efforts to do so. In early September 2005, EU foreign policy director Javier Salona told the Chinese that it was still the EU’s long-term objective to lift the embargo.47 While some may argue that much-threatened American retaliation would follow the sale to China of a weapon as potent as a modern submarine, it is worth noting that the United States does little submarine business with continental Europe, and some companies, particularly French, may not be deterred from seeking PLA sales. It is significant that Europeans have been deterred by Chinese threats of retaliation if they sell submarine designs to the United States to facilitate new submarine sales to Taiwan.

It must be emphasized, moreover, that the EU embargo has not prevented submarine technologies from going to the PLA. For example, Germany argues that its sale of MTU 16V 396SE marine diesels involves dual-use technology, though they power both the Song SSKs, and possibly the Yuan as well. This is not a simple component purchase: it requires great knowledge of the submarine. As a German corporate official explained, the Song experienced trouble during the 1990s because Israeli consultants could not meld the disparate technologies then being employed. He implied that the Germans could and perhaps did.48 There is substantial cooperation on fuel cell technology between the Dalian Institute, Germany,49 and with other countries. PEM fuel cells, with an output of 30–40 kW on Germany’s new Type 212 submarine, allow it to cruise for 420 NM at eight knots speed, or a longer range at a slower speed. Other sources suggest that this may confer the ability to remain underwater for fifteen–seventeen days,50 significantly increasing the submarine’s tactical flexibility. Germany’s newer Type 214 submarine is slated to use more powerful PEM fuel cells with 120 kW output. French DUUX-series sonar sold during the 1980s is used on the Type 035, and likely influenced the Song’s flank array sonar.

Looking toward a post-embargo period, there is much that Europe could offer the PLAN’s submarine sector. Britain, France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden are all working on UUV concepts to fulfill a range of military missions.51 Germany’s Type 212 and 214 SSKs are perhaps the world’s most advanced, using new fuel-cell based AIP systems, and the latest combat system technologies.52 More recently, Germany is developing antitorpedo defenses, towed satellite communication buoys, and even miniature unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) launched from tubes in the sail, to aid submarine surveillance.53 France, whose Agosta SSK appears to have influenced the Song’s shape, could also offer its Mesma AIP system along with other advanced submarine weapons and systems. France also has long experience with SSBNs and makes the smaller Rubis SSN. Its nuclear submarine technology sector may eventually be allowed to sell similar systems to China. Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands likewise produce SSKs and may be tempted by commercial opportunities in a post-embargo world. Britain also has a significant domestic nuclear-submarine sector capable of producing modern SSNs, SSBNs, and their related weapons and systems.

Beyond the sale of ASW torpedoes to the PLAN in the 1980s, it is not known if the United States has sold or given the PLA substantive submarine related technologies. However, the late 2005 exposure of the alleged Chi Mak spy ring suggests that China may have gained substantial insights into advanced U.S. submarine designs and capabilities. One U.S. official offered a chilling assessment to the Washington Times: “China now will be able to track U.S. submarines, a compromise that potentially could be devastating if the United States enters a conflict with China in defending Taiwan.”54 In addition, one has to consider that there may have been an indirect transfer of U.S. technology if Russia has chosen to sell the PLA knowledge obtained from the Walker-Whitworth spy ring. Such sharing might include knowledge of U.S. war planning procedure, SSBN operations, and the capabilities of Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) arrays.55 While such data would be dated today, when combined with purchased information on how the Soviets used the data to their advantage, Beijing might gain numerous insights into U.S. SSN, SSBN, and ASW practice. This might be of some use to China in developing future offensive tactics against U.S. SSBNs.

Perhaps the more profound U.S. impact on China’s submarine program has been the influence of the U.S. example as it gained and then maintained world leadership in nuclear submarine technologies. Even at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, when some engineers were afraid to do so, the U.S.-influenced teardrop hull form was chosen for the Type 091 Han-class SSN.56 It is likely that Chinese submarine designers remain keenly focused on U.S. technological advances57 and debates, and will continued to be influenced by U.S. Navy choices. As the U.S. Navy moves to investigate future submarine designs that stress modularity, novel electric drives, and laser and other energy weapons, it can be expected that China will also consider such capabilities for its future submarines.58

The PLA’s long-standing ambition to deploy a second-generation SSN was realized in December 2002 with Russian assistance.59 Asian sources revealed that the second Type 093 was launched in late 2003.60 A third is expected to be launched in 2006.61 In 2003, the Pentagon reported that there could be four 093s launched by 2010.62 Other sources report that eventual production could reach six to eight units.63 The first unit was reported to have commenced construction in 199964 and was expected by the Pentagon to enter service in 2005.

Rubin Bureau assistance for Chinese nuclear submarines is reported to include new hull coatings to reduce radiated noise.65 However, Rubin or other Russian submarine concerns potentially would have been able to offer a range of technologies, including overall hull design, engine and machinery quieting, combat system design, as well as weapon systems and countermeasures outfitting. If the 093 is in fact similar to Russia’s Victor III, then Russian contributions based on this design would have been eased considering that this SSN was built in the Komsomolsk shipyard near Vladivostok, and thus proximate to China.

To date there are no known open-source complete photographs of the Type 093 that would allow an assessment of its degree of Russian influence. However, in April 2004 an Internet picture of a purported Type 093 sail appeared. The photo does show enough similarities with the Han sail to lend credibility, but also shows that the PLAN has chosen a sharp-tall vertical sail design over the low, long, and sometimes thick Russian SSN sail preference. In 1997 ONI artists projected that the 093 would feature a teardrop hull similar to the U.S. Skipjack-class, but the projection does not match the sail of the 2004 photo. A PRC artist’s projection from a 2001 issue of the mainland Chinese magazine Modern Ships showed the 093 with a bow structure that resembles that of the Russian Victor- or Akula-class nuclear attack submarines.66 This would tend to support U.S. expectations for the Type 093. However, this may also be disinformation, and it may suggest that the Type 093 has a large spherical-bow sonar array and side-mounted torpedo tubes consistent with some Russian descriptions and models of the Project 885 Yasen.67 The PRC artist’s projection also shows six flank sonar arrays on the 093 for passive sonar detection. It illustrated the 093 launching a cruise missile from a torpedo tube.

If the 093 succeeds in matching or exceeding the Victor III’s performance, then it would represent a significant advance in PLAN SSN technology over its first-generation Project 091 Han class. Russia’s Victor III is rated nearly as quiet as early models of the U.S. SSN-688 Los Angeles class.68 However, it should be expected that the PLA would seek further Russian-developed quieting advances that help make the Project 885 nearly as quiet as the Sea Wolf (SSN-21).69 In the early 1990s Russia experimented with propulsor technology on a Kilo.70 Some illustrations of the Project 885 Yasen show that it uses a propulsor. Furthermore, the Victor III uses a sophisticated sonar system, which includes bow, flank-mounted, and towed sonar arrays. The Type 093 can be expected to incorporate either Russian- or PLA-designed sonar of each type. In addition, inasmuch as the Victor III’s maximum dive depth is said to exceed four hundred meters,71 perhaps up to six hundred meters, it is possible that the Type 093 may also be able to reach these depths. This would exceed the reported maximum depth for the 688-class SSN, and complicate detection in deep-ocean areas.

Regarding weapons, comparison with the Victor III and Chinese sources72 suggest that the Type 093 will be armed with both regular 533mm width and the exceptional Russian 650mm torpedo tubes. The latter would allow the Type 093 to use Russia’s unique class of heavy torpedoes, including the TT-5. Twice the weight of the largest Russian 533mm torpedoes, these are designed for long-range strikes against large combat ships such as aircraft carriers. In addition, it can be expected that the Type 093 will carry a range of other Russian and indigenous designed weapons. These might include the Russian Shkval rocket-propelled supercavitating torpedo or a new PLA-designed version of this weapon, and Novator Klub-S long-range antiship missiles. It is also likely that by the end of the decade that the Type 093 SSNs will be equipped with new PLA-designed LACMs.

As the United States considers truncating the planned thirty-ship production run for the SSN-774 Virginia in favor of more advanced SSNs,73 it is necessary to consider that the PLAN may be developing advanced versions of the Type 093 or perhaps a new class of SSN for the early or middle part of the next decade. Russian success with Project 885 might allow a more rapid transfer of early versions of the advanced technologies developed for this class, if they have not been already sold to China. This possibility is also suggested by reports in early 2006 that Russia plans a new five-thousand- to six-thousand-ton SSN to counter the SSN 774.74 PLA interest in UUVs and advanced cruise missiles may lead to their incorporation into subsequent SSNs.

In 1997 ONI estimated that the first Type 094 SSBN would be ready by 2005,75 while the Pentagon expected a launch “by the end of the decade.”76 The PLAN, however, exceeded these projections by launching the first Type 094 in July 2004.77 In 1997 ONI estimated that three 094s would be completed by 2010, while other reports suggest that the PLA may build a total of three to four 094s.78 Jane’s expects the second Type 094 to be launched in 2006.79

Following the example of the relationship between the 091 SSN and the 092 Xia SSBN, it is expected that the 094 SSBN will be based on the new 093 SSN. As such, the 094 will also incorporate Russian design assistance from the 093. In 1997 ONI projected that the 094 would be equipped with sixteen tubes to carry the new JL-2 SLBM. But in 2004 ONI changed this projection to twelve JL-2 SLBMs, a number also reported by Jane’s.80 If the 2006 Internet-source photo of the Type 094 is correct, this may be the main projection for which ONI was correct. This photo shows the Jin to be an evolution of the Xia, but with a higher post-fin housing for the larger JL-2 SLBM. This photo, however, does not show the missiles farm to feature a slight separation as in the 2004 ONI projection. A Chinese source notes that the 094 may be quieter than Russia’s most advanced SSBN, the Typhoon.81 This projection, however, is contradicted by the 2006 photo, which shows the Jin to contain numerous water ports, which would tend to generate noise, especially at higher speeds.

While it does remain possible that the Jin has benefited from Russian internal quieting, propulsion, sonar, and combat systems, that cannot be ascertained from the 2006 photo. It must be considered, however, that China has attempted to gain access to some Russian fourth-generation submarine technologies to improve the Type 094. An advanced development of the Delta-IV SSBN, the Project 955 reportedly displaces fourteen thousand tons surfaced and may be capable of a maximum 450-meter dive depth. According to one report it does not use a new large spherical bow sonar array, but rather a version of the SKAT sonar array with 2 x 650mm and 4 x 533mm torpedo tubes placed above. Some illustrations of the Project 955 show that it employs two propeller screws, a feature that may enhance its combat survivability.82

While a possible sale of advanced Russian SSNs or SSGNs to China may be seen as a declining possibility as the PLAN succeeds in perfecting the Type 093 SSN, there are reasons to continue to search for relevant indications. As Russia has relaxed previous limits on selling strategic systems such as the Backfire bomber to China, it is possible that it may also consider selling whole SSNs or SSGNs, especially if that might aid Russia’s submarine development by providing otherwise unavailable funds. Indications of the PLA’s interest in this ship include reports that a PLA officer perished on the Russian Oscar II SSGN Kursk when it sank in August 2000 following an onboard explosion.83

A possible sale of the Akula II SSN to the PLAN is made more realistic by India’s apparent decision to purchase two of these SSNs. Were that to occur, sale of the latest Akula II would provide an immediate boost to the PLAN’s antisubmarine and antisurface capabilities. Currently the most modern SSN in Russian service, it is also among the most capable and effective SSNs in use today. The Akula II SSN’s design is thought to have radiated noise levels lower than those of the U.S. SSN-688I class.84 It incorporates active noise-reduction technology and is credited with a maximum operational dive depth of six hundred meters,85 which is reported to be matched in the West only by the new SSN-21.86 For emergency operations, however, the Akula II may be able to dive as deep as eight hundred meters.87

After buying two export-model Project 877EKM Kilo SSKs, the PLAN acquired two more advanced Project 636 Kilos, delivered in 1998 and 1999. The 636I incorporates significant improvements in quieting. These include elastic drive shaft couplings, a slower RPM skew-back seven-bladed propeller, and new sonar designed to monitor hull and propeller-generated noise.88 The 636 is said to be almost as quiet as the U.S. 688-class SSN.89 This version is also slightly larger, faster, and has a greater range than its predecessor.

A contract to purchase at least eight more Kilos was signed in May 2002.90 To ensure their delivery by 2005–06, this batch of 636 Kilos were built in three Russian yards: five were to be built at the Admiralty Shipyards in St. Petersburg, one at Krasnoye Sormovo shipyard in Nizhny Novgorod, and two in Severodvinsk. In mid-2002 the decision to shift two Kilos from the Komsomolsk-na-Amur to Severdovinsk was criticized because the latter had not built diesel-electric submarines for forty years.91 But by mid-2003, Kilo construction was underway at Severdovinsk.92 Two from St. Petersburg were delivered to China by August 2005. All eight Kilos were delivered in 2006.

This new batch of Kilos likely consists of an improved model that could include most of the improvements slated for the 636M Kilo.93 Expected improvements in the 636M may include increased missile stowage, an integrated weapon and machinery control system, an ability to launch larger missile salvos, upgraded digital sonar with mine-detection capabilities, improved target classification, non-hull-penetrating periscope and radar, better batteries, and eventually, perhaps, new fuel cells.94

This batch of eight 636M Kilos will be armed with the Klub-S antiship system comprised of three missiles. The 3M-54E uses a subsonic first stage that incorporates a rocket-propelled second stage, which is released twenty–sixty kilometers from the target. This second stage, then accelerates to Mach 3 to defeat ship defenses. A land-attack capability is provided by the three-hundred-kilometer-range 3M-14E, which uses radar for terminal guidance. A long-range antisubmarine strike capability is provided the by small 91RE1 torpedo, which has a maximum fifty-kilometer range.95

During the December 2003 visit of Defense Minister Cao Guangchuan, there were Russian reports that Moscow was considering selling the PLA the ability to co-produce up to twenty more conventional submarines.96 While there have been no subsequent reports, as the current Kilo contract nears completion it is likely that Russia will seek follow-on orders. If there are such orders or co-production, it can be expected that Russia will offer further improvements such as new AIP systems, more advanced weapons, or provision for larger vertical-launched missiles.

In May 2004 Wuhan Shipyard launched the first of a new class of SSK, the Yuan class.97 A second was reportedly launched in December 2004. This SSK has also been called the “Chinese Amur”98 due to its resemblance to the Russian Project 677 Lada/Amur-1650 class. This similarity is apparent in the Yuan’s overall dimensional ratios, the shape of the sail, and the use by both of a step on top of the hull, which may indicate a single-hull configuration. The “step” on the hull is used to facilitate aft-sail placement for vertical-launched antiship missiles in other versions of the Amur. The Yuan also appears to exhibit the Russian preference for excess buoyancy for better combat survivability.

Much less is known about the Yuan’s engine, quieting, combat system, and weapons system outfit. A Rubin promotional video viewed in early 2006 indicates the Lada has broadband acoustics significantly improved over the Kilo 636.99 If there were substantial Russian input into the hull design, it would then follow that Russian systems may also dominate the rest of the submarine, with the possible exception of using co-produced German marine diesel engines. The precedent of using Russian components for new weapons is not unknown, as demonstrated by the PL-12 active-guided air-to-air missile and the Type 052B Luyang I DDG. There is also the possibility that such a transfer was enabled by Chinese financial support for the Lada, which began as a private venture by the Rubin Bureau to produce a less expensive SSK for littoral missions. The fact that both were launched in 2004 may indicate that China was buying components as they were being developed for the Lada.

Should the Yuan approximate the capability and mission of the Lada, this SSK may be the ultimate replacement for the Type 035 Ming, assuming the littoral missions to allow the Kilos to venture further out to sea. However, this may not be the case should it prove that future Yuans incorporate new AIP systems, as is often rumored. In that case, they may join the Kilos on more distant missions.

The 2003 DoD PLA report notes, “The SONG is a blend of Chinese and Western technology and has several key features that point to a major shift in diesel submarine design philosophy.”100 In 1997, ONI estimated that the PLAN would have about six Song submarines by 2005 and close to ten by 2010.101 Other projections indicate that twelve may be launched by 2005. A higher rate of production is possible now that the Song is being built in two shipyards, Wuhan and Shanghai (Jiangnan).

However, for a period in the mid- to late 1990s, this submarine’s future was in doubt as the first Type 039/Song was reported to have dissatisfied the PLAN, because it was too noisy and failed to successfully integrate German MTU diesel engines, Israeli electronics, French sonar, and (possibly) Russian weapons.

Improved Type 039A submarines, perhaps with Russian help, are reported to have been more successful, especially in reducing radiated noise.102 Pictures of a new Project 039 released by the PLA in 2001 showed that it lacks the distinctive step sail of the first 039, thereby improving hull-noise dynamics. The Type 039 resembles the French Agosta-90B-class conventional submarine but there is no open reporting that indicates that France provided any assistance. The 039 is armed with a Chinese-designed antiship missile based on the YJ-81 and potentially, the longer-range YJ-82. It may carry the new C43 PRC-made wire-guided torpedo and the Russian Test-71ME wire-guided torpedo.103 Chinese television coverage of the 2004 visit of a Song to Hong Kong illustrated its extensive use of digital systems in the control room, which suggests the utilization of more modern automatic combat control systems.

As the PLA Navy has come to rely on Russian submarines and related technology to propel its modernization, it follows that it has purchased several new types of Russian torpedoes for its new submarines. Two Russian torpedoes that reportedly arm Kilo submarines are the Test-71ME and the Set-65KE.104 Both are wire guided, allowing the crew to direct the torpedo based on targeting data gathered either by ship sonar or from sonar on the torpedo. These two Russian torpedoes have the capability to home in on a ship’s wake. Inasmuch as the Kilo 636 is equipped to fire the heavy TE-2 wire-guided torpedoes from two of its launch tubes, it is very possible that PLAN has that weapon. The TE-2 has a deadly four-hundred-kilogram warhead, which would be effective against large ships like aircraft carriers or provide a greater single shot kill probability against a submarine. While the U.S. Navy has an active antitorpedo torpedo program, it has not yet fielded a system capable of defending ships from wake-homing torpedoes.

When discussing trends in PLA submarine modernization, the 2003 Pentagon PLA report notes, “A second major improvement entails the use of advanced mobile mines to augment the Navy’s large inventory of submarine-laid mines.”105 While the Pentagon was not specific, this could be a reference to the possible purchase by the PLA of Russian mobile and deep water antisubmarine mines. Mobile mines can refer to mines which travel horizontally, like torpedoes, to a pre-set distance, or moored mines which detach a torpedo when a target is within range. The PLA Navy possesses a large inventory of mines, including the indigenous EM-52 and EM-55, which are both moored rocket-propelled mines.106 It also has a self-propelled mine with a range of more than thirteen kilometers. The PLAN would likely seek Russian mines with similar capabilities to complement its growing inventory of Kilo submarines. The PMK-2 is a deep-water moored mine designed primarily for antisubmarine missions. This could be laid by Kilo submarines in the likely approaches that U.S. submarines might take to reach Taiwan. In addition, Russian SMDM self-propelled mines would be useful for attacking well-defended ports from a stand-off distance.

When considering the impact of foreign technology on China’s submarines it is also important to consider how this will better enable future Chinese submarine sales to others. Since at least the September 2004 Pakistan IDEAS arms show, China Shipbuilding has been marketing the Type 039 Song-class SSK. At that show Pakistani navy officials noted that they would be considering Chinese designs in addition to European designs for their next class of conventional submarine.107 As Pakistani is suspected of having shared crashed U.S. Tomahawk cruise missiles to better help China assist the development of its new Babur land attack cruise missile,108 it is possible that Pakistan would share advanced French submarine technologies with China. France has sold Pakistan its new Mesma AIP system to be placed in the latest Agosta submarines now being built in Pakistan. Onward transfer of this technology could improve future versions of the Song and Yuan, or help China to develop countermeasures to French and other Western submarines.

In addition, one cannot discount that China might also sell nuclear submarine technologies. This is at least suggested by China’s record of selling Pakistan nuclear-bomb, solid-fuel ballistic-missile, and cruise-missile technologies. Should Pakistan desire to match a future Indian SSN capability, it is possible that China would oblige. Other countries seeking to build nuclear-powered submarines, like Brazil109 (which already has extensive space and satellite cooperation with China), could be tempted to turn to China for nuclear submarine technologies as well.

Foreign submarines and related technology, especially from Russia, have been critical to the PLAN’s ongoing rapid transformation of its submarine combat capabilities. While relatively little is known about the degree of Russian assistance to China’s new SSNs and SSBNs, the prospect that they may contain—now or in the future—significant fourth-generation Russian technology should cause concern in the West. When considering the future Chinese submarine challenge to the United States and its allies, beyond any specific foreign technology, one emerging trend that should spark particular concern is the possibility that China may move toward a more Russian-style submarine design system featuring greater internal competition. This served to accelerate late Cold War Soviet submarine performance, and could similarly accelerate China’s indigenous conventional and nuclear submarine development.

However, despite China’s current dependence on foreign submarine technologies and influence, China’s objective is to become an innovator or leader in submarine technology. Though a decade ago as the PLAN struggled with its SSK and SSN programs this prospect may have seemed distant, it would be unwise to underestimate China’s determination to succeed or the willingness of China’s current leadership to marshal the necessary resources. By mastering Russian technologies that may be associated with its third- or even fourth-generation submarines, it is possible that China could produce world-class submarines based largely on indigenous technologies within a decade. Mastery of advanced SSN and SSBN doctrine and operations is another matter, but given time and resources the PLAN will make rapid progress there as well.

1. While a full assessment of the impact of foreign technology on China’s submarine modernization is limited by the paucity of open sources, the existing open data do allow for the assemblage of a rough estimate of conditions and trends. Of specific use have been public statements by the U.S. intelligence community, both in the annual U.S. Department of Defense reports on the PLA and less frequent statements by the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, reports in the defense media, and interview data gathered by the author. This paper also builds on the author’s previous study, The Impact of Foreign Weapons and Technology On The Modernization of the People’s Liberation Army, A Report for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, January 2004, http://www.uscc.gov/researchpapers/2004/04fisher_report/04_01_01fisherreport.htm.

2. For further background on China’s recent submarine growth, see Lyle Goldstein and Bill Murray, “China’s Subs Lead The Way,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2003, 58–61; and “Undersea Dragons, China’s Maturing Undersea Force,” International Security, Spring 2004.

3. Charles Snyder, “Navy officer warns of Chinese subs,” Taipei Times, July 27, 2004, 3.

4. As of 2006 the USN operates fifty-four SSNs. Future SSN force levels are uncertain, but are estimated to range from forty-five to thirty-seven. See Christopher P. Cavas, “U.S. Navy Lays Out 30-Year Fleet Plan,” Defense News (March 28, 2005): 1; Bryan Bender, “Navy Eyes Cutting Submarine Force,” Boston Globe, May 12, 2004.

5. You Ji, The Armed Forces Of China (London: IB Tauris, 1999), 164–65; Cole also considers the possibility of the PLAN’s adopting a Bastion-like strategy if its Type 094 SSBN is successful, see Bernard D. Cole, The Great Wall at Sea: China’s Navy Enters the Twenty-First Century (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2001), 168–69.

6. Prasun Sengupta, “Full Steam Ahead,” April 12, 2005, Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS), Journal Code: 9302

7. A possible realistic estimate of a 5,400 NMI range for the JL-2 is graphically illustrated by the Office of Naval Intelligence, Worldwide Maritime Challenges 2004, 37.

8. Massimo Annati, “UUVs and AUVs Come of Age,” Military Technology (June 2005): 72–78.

9. “Japan Eyeing Radar System to Defend U.S. From Missiles,” Asahi Shimbun, October 18, 2005.

10. The Yulin nuclear submarine facility was first disclosed to the author as an underground nuclear submarine base by Asian officials in late 2002. The existence of this facility was subsequently confirmed by officials from two other Asian countries. In late 2004 the facility’s existence was further confirmed to the author by a PLA General, who described it as an above-ground nuclear submarine facility. In early 2005 Internet-source photos showed a Han-class SSN visiting a South Sea Fleet base, presumed to be Yulin. This has also been reported to be an “underwater” base as well, see Sengupta, op. cit. In early 2006 the author was also able to view this new base on Google Earth, and confirmed that this facility did include a structure consistent with the opening for an underground submarine pen.

11. Interview with the author, November 2005.

12. Hualien has an international port, and is also nearby large underground air force basing facilities that could also support SSBN and SSN missions. In addition, the often sheer rock coastal formations in this region may facilitate underground SSN/ SSBN basing. The PLA has significant experience in tunneling to create revetments.

13. Disclosed to the author by a PLA officer in November 2004.

14. Chin Chien-li, “PRC is preparing to form a space force,” Chien Shao, July 1, 2005, 52–55; “China’s ‘Space Army’ Is Taking Shape,” Hsiang Kang Shang Pao (October 13, 2005): 4.

15. Under the names KT-1 (DF-21), KT-2 (DF-31), and KT-2A (DF-31A), these mobile land-based SLVs were marketed at the 2002 and 2004 Zhuhai Airshows.

16. Liu Huanyu, Dalian Naval Academy, “Sea-Based Anti-Satellite Platform,” Jianchuan Kexue Jishu [Ship Science & Technology], February 1, 2004.

17. Interview, August 2005.

18. Russia’s NPO Mashinostroyenia has sold China its >1m resolution KONDOR series of e/o and radar satellites, eight of which could be lofted by 2010, and at the 2002 Zhuhai Airshow the China Aerospace Corporation revealed two data-relay satellite designs.

19. Yihong Chang, “Is China Building a Carrier?” Jane’s Defence Weekly, August 17, 2005; Vladimir Dzaguto, “From the Varyag into a Target,” Vremya Novostey, October 18, 2005; interviews, Moscow Airshow, August 2005.

20. Interviews with the author, October and November 2004.

21. In a similar manner, the PLA’s aircraft design sector benefited greatly from the adoption of the French Dassault CATIA computer-aided design and computer-aided modeling programs.

22. “094 Project Makes New Progress,” Kanwa Defense Review (March 1, 2005): 3.

23. The importance to the Chinese of both open-source and espionage-gathered information on nuclear submarines, from the late 1950s onward, is amply illustrated in chapter three of John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China’s Strategic Seapower (Stanford Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994), 47–73.

24. “Former Defense Agency Official Leaks Intelligence—Shadow of Subtle Chinese Espionage Activities,” Tokyo Shimbun, April 26, 2005.

25. “Russian Customs Seize Submarine Being Exported to China for Scrap,” Agentstvo Voyennykh Novostey, May 5, 2005.

26. Bill Gertz, “Four Arrests Linked to Chinese Spy Ring,” The Washington Times, November 5, 2005; Greg Hardesty, “Spy Suspects Blended in, the FBI Believes Four In-Laws Were Involved in Stealing Information from an Anaheim Defense Contractor to Deliver to China,” The Orange County Register, November 11, 2005.

27. “Money from Sea Depths, Submarines for Export,” October 2005, http://www.kommersant.com/page.asp?idr=529&id=614878.

28. “Russia Helps China Take New SSNs into Silent Era,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, August 13, 1997, 14.

29. U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, Worldwide Submarine Challenges, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, February 1997, 23.

30. Report to Congress Pursuant to the FY2000 National Defense Authorization Act, Annual Report on the Military Power of the People’s Republic of China, July 28, 2003, 27, hereafter called “DoD PLA Report, 2003,” http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/20030730chinaex.pdf.

31. Worldwide Maritime Challenges 2004, op. cit.

32. “CIA Report Reviews Weapons Proliferation Trends,” http://www.cia.gov/cia/reports/721_reports/jan_jun2003.htm.

33. Norman Polmar and Kenneth J. Moore, Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines, 1945–2001 (Dulles, Va.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2003), 319.

34. Ibid.

35. Worldwide Maritime Challenges 2004, op. cit.; “Type 094 Class (SSBN),” Jane’s Fighting Ships Internet Edition, posted 03 August 2005; Polmar and Moore, 319–21.

36. For example, in the early 1990s Russia refused to sell the Tupolev Tu-22M3 Backfire to China, but in August 2005 was reportedly in the middle of negotiations to sell this bomber to China.

37. This is an oft-heard refrain from Russians at numerous arms shows.

38. “Russia in a Hurry to Sell Arms to China,” December 18, 2003.

39. The first Project 677 St Petersburg was reportedly inspected by the Chinese in mid-2005; see “Conference Announces Kilo-Class Subs Remain Russia’s Top Naval Export,” ITAR-TASS, July 1, 2005.

40. “China to Remain Largest Russian Arms Importer in Coming Years,” Interfax, July 17, 2000; Pavel Felgenhauer, “No One Is Fooled by MND,” Moscow Times, May 31, 2001; “Official says improved Russia-West ties have no effect on arms trade with China,” Moscow Agentstvo Voyennykh Novostey, May 31, 2002 in FBIS, CEP20020531000249.

41. See Richard Fisher, Jr., “Military Sales to China: Going to Pieces,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief, November 21, 2002.

42. The Malachite bureau was promoting both fuel-cell- and chemical-based AIP systems at the 2004 IDEX show while the Rubin bureau is promoting a fuel-cell-based AIP system for the new Lada/Amur SSK. Rubin has in the past offered hull-plug AIP insert modifications.

43. “094 Project Makes New Progress,” Kanwa Defense Review (March 1, 2005): 3.

44. Robert Karniol, “China Buys Shkval Torpedo from Kazakhstan,” Jane’s Defence Review (August 26, 1998): 26.

45. Interview, Taiwan, December 2001.

46. Novator officials confirmed that China was a customer for the CLUB-S system at the 2005 Moscow Airshow.

47. “Solana says lifting of China arms embargo on long-term agenda,” Agence France Presse, September 6, 2005.

48. Interview, November 2002.

49. Announcement, Second Sino-German Workshop on Fuel Cells, April 13–15, 2003, Guenzburg, Germany, http://www.zsw-bw.de/FuelCellWorkshop/general.php.

50. Joris Jansen Lok, “Germany’s Submarines Combine Export Success with Propulsion Progress,” Jane’s International Defense Review (January 2002): 49.

51. Annati, “UUVs and AUVs Come of Age,” 78–80.

52. In 2004 a German woman resident in Canada who was hired to translate weapons control documents related to the Type 212 was arrested in a Canadian counterintelligence “sting” after she offered to sell the documents to the Chinese embassy in Canada. The incident at least suggests knowledge of China’s interest in the Type 212 by her German employers, see “German translator in Chinese espionage scandal involving the world’s first fuel cell submarine,” Deutsch Presse Agentur, December 15, 2004.

53. Hendrik Goesman, “Neue U-Boot Technologie,” Strategie und Technik, October 2005.

54. Gertz, “Four Arrests Linked to Chinese Spy Ring.”

55. Polmar and Moore, Cold War Submarines, 173, 285.

56. Lewis and Xue, China’s Strategic Seapower, 56–57.

57. For example, see “Shape-memory alloys,” Binqi Zhishi [Ordnance Knowledge], (September 2004): 75, which describes how the U.S. Navy may use this novel technology to move rudder/elevator functions to the propulsor shroud on SSN-774 class submarines, and that a full scale system may be available in 2007.

58. For U.S. submarine aspirations, see Mark Hewish, “Submarines to cast off their shackles, take on new roles,” Jane’s International Defence Review (March 2002): 35–43; Andrew Koch, “US Considers Alternative Submarine Propulsions,” Jane’s Defence Weekly (October 8, 2003): 6.

59. DoD PLA Report 2003, 27.

60. Interview, April 2004.

61. Interview, November 2005.

62. DoD PLA Report, 2003, 27.

63. Hui Tong, “093,” Chinese Military Aviation, http://mil.jschina.com.cn/huitong/han_xia_kilo_song.htm.

64. A. D. Baker, The Naval Institute Guide to Combat Fleets of the World: Their Ships, Aircraft, and Systems (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2002).

65. “Russia Helps China Take New SSNs into Silent Era,” Jane’s Defence Weekly (August 13, 1997) 14.

66. Artist projections of the Project 093 and 094 appeared in the PRC naval magazine Guoji Zhanwang and were viewed on the Internet in late 2000.

67. This possibility is reported by Anatoly Efimovich Taras, Atomic Submarines, 1955–2005 (unknown Russian publisher), 2005, 194, viewed on the Key Forum, http://forum.keypublishing.co.uk/showthread.php?p=818044#post818044.

68. Rupert Pengelley, “Grappling for Submarine Supremacy,” Jane’s International Defense Review (July 1996) 51.

69. This estimate is provided by Polmar and Moore, Cold War Submarines, 319.

70. “Pumpjet Possibility for Russia’s Private-Venture Amur,” Jane’s International Defence Review (February 1997): 19.

71. “Victor III (Project 671RTM(K)),” IMDS 2003, International Maritime Defense Show, St. Petersburg, 25–29 June; see also Vladimir Shcherbakov, “Soviet Underwater Predators: A Story of the Victor Family Attack Submarines,” Arms Defense Technology Review (Moscow), 2 (15) 2003, 38.

72. Jian Je, “Shenhou Zhong de Xuangzi Zuo” (Myth of the Twins), Guoji Zhanwang (August 2002): 23, cited in Lyle Goldstein and Bill Murray, “China’s Subs Lead the Way,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings (March 2003): 59.

73. Andrew Koch, “Funding Curb Forces Virginia Reality Check,” Jane’s Defence Weekly (January 26, 2005): 4.

74. “Russia to build next generation submarine,” Xinhuanet, February 8, 2006.

75. U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, Worldwide Submarine Challenges.

76. DoD PLA Report, 2003, 31.

77. Bill Gertz, “China Tests Ballistic Missile Submarine,” The Washington Times, December 3, 2004.

78. Hui Tong, “094,” Chinese Military Aviation, http://mil.jschina.com.cn/huitong/han_xia_kilo_song.htm.

79. “Type 094 Class (SSBN),” Jane’s Fighting Ships Internet Edition, posted 3 August 2005.

80. Ibid.

81. “Zhongwai He Qianting Bijiao” (A Comparison of Chinese and Foreign Nuclear Submarines), Jianchuan Zhishi (September 1998): 30, cited in Goldstein and Murray, “China’s Subs Lead the Way.”

82. Taras, Atomic Submarines, 1955–2005.

83. Steven Ashley, “Warpdrive Underwater,” Scientific American, May 2001, 79.

84. Polmar and Moore, Cold War Submarines, 319.

85. “Akula (Project 971),” IMDS 2003, International Maritime Defense Show, St. Petersburg 25–29 June, 17.

86. David Miller, Submarines of the World (St. Paul, Minn.: MBI Publishing, 2002), 382.

87. A. D. Baker III, Combat Fleets of the World, 2002–2003 (Annapolis, Md.: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2002).

88. Rubin brochure.

89. Rupert Pengelly, “Grappling for Submarine Supremacy,” Jane’s International Defense Review (July 1996): 51.

90. “Russia, China ‘Satisfied’ With Joint Military Commission Meeting,” Interfax, June 1, 2002, in FBIS, CEP20020601000050; “China Major Buyer of Russian Arms,” ITAR-TASS, May 29, 2002, in FBIS, CEP20020529000144.

91. Mikhail Khodarenok, “Underwater Scandal,” Nezavisimaya Gazeta, June 7, 2002, 6.

92. Vladimir Anufriyev, “Russia Inaugurates Construction of Submarines for China,” ITAR-TASS, June 3, 2003, in FBIS, CEP20030603000328.

93. John Dikkenberg, “Regional Submarines: Just How Good Are the Kilos,” Asia-Pacific Defence Reporter (November 2002): 17.

94. Ibid.

95. Military Parade, Russia’s Naval Ships, Armament and Equipment (Moscow, 2006): 101–3; Novator brochures.

96. “Russia in a Hurry To Sell Arms to China,” December 18, 2003.

97. Bill Gertz, “Chinese Produce New Type of Sub,” The Washington Times, July 16, 2004; “YUAN (Type 041) (SSK),” Jane’s Fighting Ships Internet Edition, posted 03 August 2005.

98. Term coined by Yihong Chang, see “Kanwa’s Appraisal of New Chinese Submarine,” Kanwa Defense Review (March 1, 2005): 13–14.

99. Rubin video viewed by author at the DEFEXP, New Delhi, February 2006.

100. DoD PLA Report, 2003, 21.

101. U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, Worldwide Submarine Challenges.

102. Glen Levick, “China,” in Asian Navies Overview, www.warships1.com, updated March 2000.

103. Mark Farrer, “Submarine force in change—the People’s Republic of China”; Kanwa News, March 11, 1999.

104. Goldstein and Murray, “China’s Subs Lead the Way,” 58.

105. DoD PLA Report, 2003, 26.

106. The EM-52 is mentioned in the “Future Military Capabilities and Strategy of the People’s Republic of China,” Report to Congress pursuant to Section 1226 of the FY98 National Defense Authorization Act (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, November 1998), available at http://www.fas.org/news/china/1998/981100-prc-dod.htm.

107. Press Conference, IDEAS, Karachi, Pakistan, September 2004.

108. Robert Hewson and Andrew Koch, “Pakistan Tests Cruise Missile,” Jane’s Defence Weekly (August 17, 2005).

109. Pedro Paulo Rezende, “Brazil Closer to Fielding SSN,” Jane’s Defence Weekly (September 14, 2005).