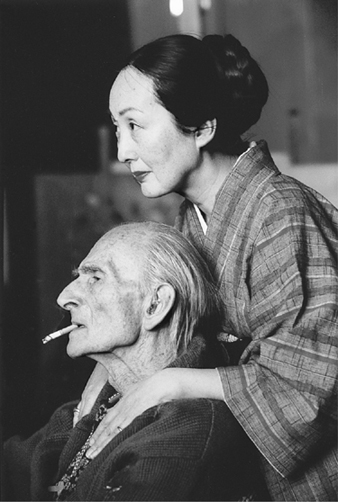

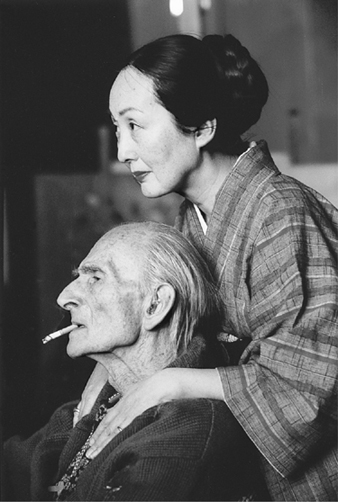

Balthus and Setsuko in 1998, by Raphael Gailliarde (photo credit 4.1)

DURING MY FIRST VISIT to Rossinière, Balthus and Setsuko urged me to read the writer Ananda Coomaraswamy. He was their ultimate “porte-parole,” Setsuko said, using the French term that literally translates to “carrier of the word” and roughly means “spokesman” or “mouthpiece.” When Setsuko said that Coomaraswamy’s books would guide me toward her husband as he wished to be understood, Balthus nodded affirmatively.

Stanislas Klossowski de Rola—clearly under his father’s close edit in the four-page preface that is, appropriately from the artist’s point of view, the sole text of his Balthus book—quotes Coomaraswamy extensively in his opening paragraph. Stanislas advises that we all adapt Coomaraswamy’s position that “the student of art … must rather love than be curious about the object of his study.”1

Coomaraswamy—a combination of art historian, philosopher, Orientalist, and linguist—was curator of Indian art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He wrote many highly theoretical books and maintains that painters are their sole appropriate spokespeople. “It will not be ‘educational’ to interpret,” he writes.

Balthus’s “porte-parole” warns viewers against thinking of artists as “expressing themselves”; the worthwhile aim of art is the use of formal means to achieve a purity and religiosity. Balthus concurred entirely. He told me that he was a “religious” artist. When I asked him to amplify, he said that if I did not understand, he could not help me further.

Ananda Coomaraswamy writes, “If a poet cannot imitate the eternal realities, but only the vagaries of human character, there can be no place for him in an ideal society, however true or intriguing his representations may be.”2 These “eternal realities,” Balthus suggested, are what he has tried to capture—far more than any specifics of his own life—which is why he finds any examination of his private persona so annoying.

Balthus and Setsuko in 1998, by Raphael Gailliarde (photo credit 4.1)

Balthus’s best paintings do, indeed, capture the eternal truths: how light falls, how children sit, how cats stare. Yet even in his most rudimentary sketches, something else beckons us.

EVERY EVENING DURING MY VISIT to the Grand Chalet in January 1991, Balthus and Setsuko and I would repair to the library after dinner for coffee or tisane. In front of the large fireplace, with a fire periodically poked by one of the smiling Filipino servants, we would eat dark chocolates and discuss books or art. On some occasions we were joined there by Harumi or Stanislas, depending on who was home. Then, because these were the days in which the Persian Gulf War was being fought, we would often go upstairs to the small, narrow television room so that we could watch the news on the French network that broadcast CNN.

The TV room was off a long corridor of the type one would expect to find in a large inn or small hotel rather than a private home. There were a dozen doors spaced at fairly even intervals on both sides of the dark expanse. One of these led to Balthus’s bedroom; another to Setsuko’s; another to the spacious, beautifully appointed bed-sitting-room in which I was staying.

One night after we had been watching the news, Balthus and I headed down the corridor together toward our rooms. Somehow we got back to the subject of Coomaraswamy. I referred to the Indian’s statement about a bomb but could not recall the exact words. Balthus, however, knew them verbatim.

Like someone reciting a religious credo, he recited, with impeccable recall: “The bomb, for example, is only bad as a work of art if it fails to destroy and kill to the required extent.”3 He enunciated these words with a look of profound delight on his face—as if he were purring.

Know your intentions, and realize them. If you have attained your goal, then your artwork is a success. If that goal is to baffle, or subjugate, your viewer, it scarcely matters, so long as you achieve what you set out to achieve. What counts is for the artist to be as competent and sure of his tools as the maker of a bomb.

AFTER OVER TWO YEARS of agonizing flights to the Spiros’ apartment in Berlin, Baladine Klossowska managed to cobble together a year for her family back in Switzerland. In the course of this winter of 1923–24, the mother became more convinced than ever of Balthus’s talents. She wrote Rilke, who was in the process of completing the Duino Elegies at Muzot:

At the house I’ve admired what he’s done. He is a great, great artist. He has shown me his picture and the ceiling; I had no idea what I was looking at! I told myself, when I saw those four apostles this morning, that what I had in front of me was a wonder, a prodigy.… Today, looking at his paintings, I told myself that perhaps everything is merely an interregnum and with such talents something has to happen, one cannot despair.—Once again, my very dear friend, B.’s paintings have tremendously impressed me … and I am terrified by the idea that he might fall ill. Especially because at the age of fifteen he is doing things which could be the work of a great painter.4

Baladine wrote this letter in late November 1923, when she was visiting Balthus in Beatenberg. Because the lad was too thin, and ate better when his mother stayed with him, she settled in, although she had initially intended only to remain there a few days. Not only was she acting upon her maternal instinct to nurture her son, but she was also advancing a genius—much as she had done by fixing the crumbling plaster for Rilke at Muzot.

She worshiped Balthus: “This child is marvelous and braver than a grown-up—than I am, for instance,” she explained.5

While tending to her son, she made a portrait of him, and then sent it to Rilke. Her lover praised it as her best work ever: “delicious, of an incomparable tenderness and melancholy charm.” Every emotion, every trait, was apocalyptic. They would rarely ever be otherwise for Balthus.

IN FEBRUARY 1993 the man who says he never gives interviews or allows himself to be quoted in print publicly reminisced in considerable detail about that winter in Beatenberg in a statement he made to Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan—the source of the pistachio nuts. These intimate recollections appeared in Alp Action, a special advertising supplement to the European edition of Newsweek.

Gazing toward windows in winter, at the mountains beyond, I discovered the great art of Chinese painting. Watching the peaks, I could see things appear, disappear and reappear as I entered a singular state of mind. Then I came across a book on Chinese and Japanese art and I realized that these works had been painted by people who, while gazing through a window, had experienced the same change of perspective. As an artist I was fascinated by this and I realized that for me, the mountains were, truly, where it all began.

The grandeur of the mountains first entered my consciousness at age four, when my parents’ cook took me shopping. Mrs. Quiblier had a poster of Mont Blanc in her dairy shop, and when I saw it I felt a yearning for mountains. During my youth, we also spent a great deal of time in the Alpine town of Beatenberg, which, incidentally, was well known to the Russian nobility. Everyone, even Dostoevski, had at some time been to Beatenberg, where there were very old and very grand palace hotels that have now all disappeared. My most profound childhood memories derive from the mountains, which are the source of all my sensitivity.

One special memory involves a feast called the distribution of cheese, a great celebration marking the end of summer. To commemorate the event, the Alpine communities of Beatenberg and Sigriswil came together each year on the 15th of September, each receiving its share of cheese. In the evening, we descended from Beatenberg and sometimes spent the night sleeping in hay. One strange night, I recall, a boy began telling the most extraordinary ghost stories and showed me what he said were the tracks of the Devil’s hooves, though I thought they might have been left by a goat or a cow. At the time, I thought it strange that people from Switzerland, such a developed country, still nurtured traditions of ghosts. But even when I settled in the Villa Medici in Rome, I never stopped missing the mountains. I painted them from the city, where I could see the light of the mountains, as in a dream.

These days, things have changed. There are high-rise buildings in Beatenberg, and this lovely Alpine region, like so many others, has been doomed by its very splendor because it attracts the whole world and too many hotels. The region is poised for the ultimate destruction of beauty, because we live in times when everything is for sale.

The statement is pure Balthus: as he was as a child, and as I have always found him to be at Rossinière. His words combine his deep affinity for the Orient, his genuine love for nature, his fascination with ghost stories, and his loathing of the way the world is changing. At the same time, it drops quiet hints about the affluence of his childhood, with no reference to the very real anxiety. And his penchant for grandeur is palpable; that aside about the Russian nobility and the palace hotels, while never actually claiming direct experience of them, falsely suggests that he had a connection to their world. There is no intimation whatsoever that the mountain village was Balthus’s refuge in a time of turmoil.

Balthus’s concluding message, however, does ring true to the most salient and stirring aspects of his art. The celebration of beauty is tempered by tragedy; the world destroys what it has; enchantment is fleeting. Little wonder that for Rilke, Balthus’s charm, tenderness, and melancholy were incomparable.

TENSIONS BETWEEN RILKE and Baladine were at a peak that winter. Rilke, suffering from the early stages of serious illness, was struggling to preserve as much energy as possible for his work. He continued to insist on his solitude. But Baladine longed to be with him at Muzot. She would not go back to the Spiros in Germany and, ever eager to cross the mountains to be with her lover, stayed instead at Beatenberg. Rilke wrote to Nanny Wunderly-Volkart that Baladine was “stubborn, selfish, insensitive, and forward.”6 Meanwhile, Baladine wrote him almost daily, imploring her great love at least to progress to tu and du from vous and sie in his letters to her. But while she longed for renewed intimacy, Rilke spent most of his time pursuing his interest in recent French literature and focusing on his own writing.

Balthus fared well in Beatenberg that winter, but he could not—yet—escape to the mountains permanently. The prodigy would be turning sixteen on February 29, 1924. And whatever conflicts the poet was experiencing with his protégé’s mother, he still gave Balthus his full affection. Rilke concluded that the time had come for him to go to Paris.

The poet felt that this was the best possible move for Balthus’s development as an artist. He had similarly steered Pierre in his career as a writer. To help organize the Klossowski boys’ lives in Paris, Rilke had enlisted the support of André Gide. The two writers had been friends since 1910, when each had come to know, and translate, the other’s work. In November 1922 Rilke had written Gide:

You know of my interest in these two sons of my friend Klossowski. It is only natural that I should think so often of them now, especially since their gracious mother is spending some of her vacation here with me. Young Baltusz (with whom I once collaborated) is also in Switzerland.7

Within a year, Gide arranged for Pierre to enter the Ecole Dramatique of the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier, directed by Jacques Copeau. Pierre initially stayed at Gide’s house, a plan to which Gide had happily consented solely on the basis of Rilke’s recommendations for this gifted young writer.

Now Rilke launched Balthus in an equivalent fashion. But both he and the artist of Mitsou opted for a different route. For Balthus, a school would have nothing to offer. Rather than waste time with any institution, he should be free simply to paint.

There was no question that he was worthy of it. He was immensely gifted as a draftsman. On Balthus’s actual birthday, Rilke wrote Baladine:

Baltusz’s drawings are very fine. It is amazing how he has sensed the life of the body, I should say, the current of its vitality; it’s like a welling-up of life of which Baltusz has realized both the freshness and the constant agitation, the unconscious stream fulfilled and renewed within the bed of this form.8

It gave Rilke vast pleasure to see the young genius embark on his new course. A week later, he wrote:

I think of Baltusz, and I am really so happy for him! A fine date to arrive in Paris: March 7!…Gide’s letter is charming; how delighted he will be with Baltusz.

So the talented youth headed to the art center of the world, under the guidance, both emotional and practical, of Rainer Maria Rilke.