Pierre Bonnard in 1937 (photo credit 5.1)

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye,

And all my soul, and all my every part;

And for this sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart.

Methinks no face so gracious is as mine,

No shape so true, no truth of such account,

And for myself mine own worth do define,

As I all other in all worths surmount.…

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, SONNET 62

BALADINE KLOSSOWSKA was soon in trouble with the Swiss police. She had failed to deposit her passport, which was German, with the authorities in Sierre when she arrived there at the start of summer in 1924. She turned to Rilke for help. The poet did his best to resolve the situation, beseeching influential friends to intervene on Baladine’s behalf, explaining that she had never before had to take care of such matters for herself and was preoccupied with the precariousness of her and her sons’ situation.

Madame Klossowska is quite alone, and doubtless the dimensions of her mistake seem larger upon reflection. The two children are in Paris, invited there by André Gide, who was so kind as to express an interest in their fate; but it is not yet certain that they will be able to remain there and arrange a future for them suitable to their talents.1

Immediately after Easter, just when Anton Contat appeared on the verge of solving her problems at Rilke’s bidding, Madame Klossowska fled to Paris. She should have straightened out her situation with the Swiss police first. But the pressures were beyond her control, Rilke explained. She simply had to be with Balthus and Pierre.

Once she managed to join her sons, Baladine saw the degree to which Rilke’s efforts on their behalf was already paying off. She happily reestablished her home base at 15, Rue Malebranche, a studio and living space near the Luxembourg Gardens where she had lived before the disruption of the war.

It was up to Rilke to resolve her problems with the Swiss bureaucracy; she could think about little other than her boys. In October she was overjoyed by further encomia for Balthus’s work from Pierre Bonnard. Bonnard had paid a call on Baladine. He praised her watercolors and they exchanged works, but what touched her above all was “the lively interest he took in Baltusz’s paintings and compositions. He was delighted with what Baltusz was doing.” Bonnard was so impressed that he had Balthus take the work to the Galerie Druet on the Rue Royale, in order to present it to Maurice Denis and Albert Marquet, as well as to Eugène Druet himself.

That distinguished group was intrigued by the work of this youth who had never had a painting lesson. Maurice Denis told the prodigy, “All you lack is a matter of ‘savoir faire’; as it is, you succeed, but with roundabout devices you can do without.” He invited Balthus to come visit him for a chat.

Baladine reported to Rilke that at that get-together Bonnard said of Balthus’s work, “I know nothing about painting but I find what he does very beautiful and extraordinary.” Everyone at the gathering commended Balthus for having started to copy Poussin at the Louvre—something his mother had done when he was a toddler. They deemed this just the right step in training his eye for composition. Following that session at Druet’s, Bonnard said to Baladine Klossowska, “He is an artist, a real artist!” She could hardly wait to repeat all of this to Rilke, whose admiration for Balthus she knew would never waver whatever the vagaries of her lover’s feeling for her.

The man “of whom nothing should be known” alluded to Bonnard’s admiration for his work in an interview in Le Figaro in 1989. Called “Balthus Parle”—the suggestion being “at last,” although there have been similar articles here and there since the 1940s—it covered an entire page of the daily Paris newspaper.2 Here Balthus let it be known that he had had an exhibition at age fifteen for which Bonnard had written a catalog preface. In truth, the entire extent of this “exhibition” and “preface” was this one-time, informal showing of a handful of works to three other people when the boy was sixteen, and Bonnard’s remarks to Baladine. Yet even if Balthus ultimately felt the need to transmogrify the details of those occurrences for the sake of the Paris newspaper readers, the actual events truly constituted a stunning start.

TO HIS MOTHER, Balthus in those early days in Paris was “very soigné and very beautiful.” She was thrilled about his success, and happy to have him receive the advice of the masters—even though it completely contradicted what she and Rilke had told him. “The odd thing,” she wrote Rilke, “is that we have always told him just the opposite: not to undertake compositions at so young an age. Here Bonnard and Denis say that he must do as much of such things as he can.”3

Pierre Bonnard in 1937 (photo credit 5.1)

In 1925 Balthus took the counsel to heart by copying Poussin at the Louvre. What he learned in this way would become a mainstay of his art. Here Balthus developed Coomaraswamy’s “formalism,” the structure and precision of arrangement that would guide his painting methodology as well as his life.

Rilke had arranged for his young protégé’s support in this endeavor by organizing funding from the Berlin industrialist Richard Weininger and his wife. At the poet’s behest, the Weiningers also financed Pierre Klossowski in the same time period. Rilke frequently wrote to these generous patrons throughout the year to tell them how much it meant to these two gifted boys to have this time for quiet work and development. The poet, sounding very much as Balthus would half a century later, bemoaned recent changes in modern society—which he felt was being damaged in two directions at once by Bolshevism and American culture. “The education the Klossowski brothers would receive, and the artistic insight it would engender, might fortify them to resist these destructive trends in contemporary life that flattened the uniqueness of the creative spirit.”4 Without their support, he told the Weiningers, Balthus and Pierre’s progress would not have been possible. But such talented youths warranted the effort, he wrote the Weiningers. “Young Baltusz is what he was from the beginning, a real artist, a painter of talent, possibly of genius.”

Rilke and Baladine began to spend a lot of time together again. The poet arrived in Paris at the start of 1925 and immediately sent his Merline “a huge bouquet of flowers.”5 He took rooms at the Hôtel Foyot, near her place on the Rue Malebranche. For the next seven months, they enjoyed day after day of seeing one another: at home in her studio apartment; walking around the city; and visiting Rilke’s friends from the worlds of literature and society, among them Paul Valéry, Jules Supervielle, the Princess Marthe Bibesco, and the Countess Anna de Noailles. It was René and Merline’s most prolonged period together, and the final one.

There were those in Rilke’s circle who were skeptical about the relationship. In his diary that year, Harry Kessler complained of Rilke having “seemingly allowed himself to be completely ensnared by Madame Klossowska.”6 Rilke’s old friend Annette Kolb “viewed Merline’s frequent presence at his side with a jaundiced eye—the great poet caught in ‘that Klossowska’s coattails.’ ”7 Regardless, Rilke and Baladine left Paris in August 1925 to go first to Burgundy and then, via Muzot, to Milan. It was a summer holiday they both seemed very much to enjoy until Rilke fell victim to food poisoning in a resort on Lake Maggiore, after which they canceled the Milan segment of their journey and returned to Sierre, where Merline took care of René at the Bellevue.

A deeply saddened Merline left her lover at Muzot in early September. Something in her may have recognized that this was the last time they would see one another. Standing at the station on the occasion of Baladine Klossowska’s departure for Paris, Rilke “believed he had outgrown the very relationship that had been one of the important vehicles of his transformation.”8 A couple of days later, seemingly cognizant of the finality of that farewell, Baladine wrote him, “Oh, René, how small you became, seen from my train, and how unreachable. My heart is overwhelmed.”9

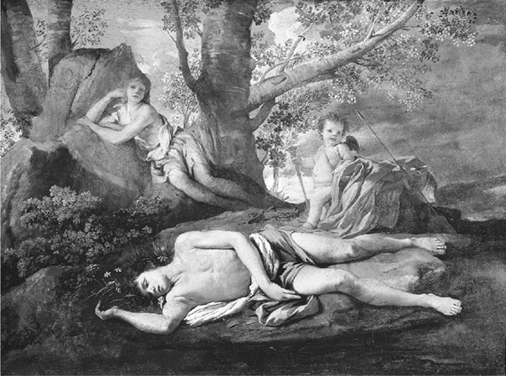

IT WAS DURING THIS LAST flourishing of his mother and Rilke’s relationship that Balthus copied his first painting by Poussin in the Louvre: Echo et Narcisse. Moreover, he intended the copy to be a fiftieth-birthday present for René. To honor his mentor and teach himself composition and spatial organization, he chose perfectly.

Balthus devoted much of 1925 to the undertaking, which provided a level of instruction no school could match. Poussin understood surfaces and texture, high drama and subtle nuance. He was a master of the careful relating of a complex array of elements. Balthus had found the ultimate guide to show him how to order life’s diversity with overriding control, taste, and poetry.

Of all of Nicolas Poussin’s major canvases at the Louvre, Echo et Narcisse, the smallest, held particular appeal for the copyist. Matisse had made a version of the painting, between 1892 and 1896, having similarly been drawn to the canvas, which was so immediate and personal compared with Poussin’s larger, more complex pictures. The dramatic scenario of Echo et Narcisse is focused and concentrated. Poussin has impeccably articulated the state of being and the physical position of each of the major figures. His rendering of Narcissus is the consummate expression of a lifeless body. The weight of the youth’s legs and torso is palpable; his arms hang entirely limp. Echo, even though she is fading away in the process of her transformation into stone, appears splendidly relaxed, recumbent on her rock. She seems surprisingly at ease—sadomasochistically, perhaps—with both her own and Narcissus’s fate. Cupid is feisty.

Knowing Balthus’s subsequent work, we can see the degree to which Poussin’s canvas nourished his imagination. The seventeenth-century painting offered an exquisite, melancholy rendition of a dead, sexy young man—whose exact position Balthus would repeat, albeit on women, in his own work for years to come. Poussin’s half-dead Echo is the prototype of even more of Balthus’s women: those modern Parisians mimicking the mythical creature’s dream state in their way of being somewhere between this world and the next.

There is a direct line between Echo and Narcissus and the characters in Balthus’s art. Poussin’s personages are both beautiful, both victims of misfortune, and they suffer from unrequited love. With their great bodies, they are incredibly tempting and seductive. But, sadly, they are never united. Poussin has depicted these godlike creatures as isolated and alone; such self-love and unfulfilled passion would permeate Balthus’s world. Unfulfilled passion is, after all, the romance that prevails in Balthus’s paintings. Beauty does not prevent—but, rather, seems to invite—aloneness.

Yet for all of the tragic separateness, Poussin’s painting surface abounds in rhythm, and the forms relate to one another as if by divine plan. Echo’s arms loop musically, their arrangement in counterpoint to Narcissus’s. A visual link is established between the two characters by the way the lines of their legs flow into one another and connect through the void between them. The curved vertical of the central tree neatly balances the sloping mass of Narcissus’s body. The angles gyrate; Cupid’s spear, his torch, and the various tree trunks have been worked out for maximum effect.

Such systems and connections would soon underlie Balthus’s own work. Qualities of Echo et Narcisse pertain to Balthus’s mature figure compositions as well as to his landscapes. In the manner of Poussin, he would develop an eye that encompasses everything. Poussin’s lighting would also find its echoes in Balthus’s art. Like theater spots, it falls clearly on the figures. The main body of the painting is divided into dark and light areas. A somber foreground leads to an ambient sky. Sunlight glows behind the foliage. The effects clarify the details and lend poignancy, even a slight eeriness, to the strange scene.

Poussin’s details have a vividness the seventeen-year-old student would forever do his best to achieve. The narcissus blossoms are lovely and delicate, their yellow stamens and white petals catching the light. Their jewel-like luminance would occur in bouquets Balthus painted at Chassy in the 1950s. The flames of Cupid’s torch truly glow, much like the fire that would rage in Balthus’s 1945–46 Beaux Jours.

In his placement of every element of the composition, Poussin was a model of dexterity and competence. He knew where to leave space around figures, and how to enliven a canvas with bold forms. He made the people dominant, and kept his landscape recessive while thoroughly descriptive. The painting is supremely well ordered—and, at the same time, rich in its nonstop motion. It also makes plausible an altered state of being, with “the dreamlike suspension of the figures and the languid nature of their pose.”10

The young artist with his easel set up in the Louvre intuited, or deliberately studied, all of this. Like Poussin, he would spin extraordinary tales in which everything had its right place. He, too, would achieve the bizarre while maintaining tremendous reserve in its expression. Poussin was a classicist, a geometrician, an artist in consummate control of characters out of control. He could neatly orchestrate disarming images in which people exist as if in a dream state: dazed, dead, or in the process of metamorphosis. Balthus would also deliberately illustrate discomfiting and ambiguous themes.

Poussin borrowed Narcissus’s pose from a sixteenth-century Pietà by Paris Bordone. Balthus would, ten years later, repeat the image, with some minor changes, in The Mountain and in The Victim. Poussin’s Narcissus instructed Balthus greatly, much as Bordone’s dead Jesus had inspired Poussin. These were exquisite renditions of creatures struck dead just while their physical beauty was at its peak. The imagery was melancholic to the point of tragedy, but the splay-legged victims, whether comatose or dead, were highly alluring specimens of humanity, of strong body and sumptuous flesh.

Nicolas Poussin, Echo et Narcisse, c. 1629–30, oil on canvas, 74 × 100 cm (photo credit 5.2)

At the same time, immersing himself in the Poussin, Balthus found a perfect single-painting course in how to paint. Echo et Narcisse was an exemplar of brilliant construction and impeccable articulation. We feel the space perfectly. Nature is graceful, color and form exquisite. Poussin depicts drapery masterfully; after all those months at the Louvre, his copyist learned the same skill to such an extent that it would last him all his life.

Years later, Balthus would still be quoting Poussin. The girl in the 1940 Cherry Tree would be a modern version of the harvester on a ladder in Poussin’s Autumn. How like Balthus to select the creature with her back turned. Poussin’s art offered any number of models for bold and brazen characters or for straightforward heroes; Balthus latched on to one of the rare quirky ones, the mysterious one, the oddball. But none of Poussin’s prototypes would prove as true to Balthus’s needs and passions as Echo and Narcissus, so gorgeous yet forever lost.

…

TOWARD THE END of November, Baladine wrote Rilke:

I went to the Louvre today to see Baltusz’s lovely copy; he’s beginning to have a public. His copy resembles Géricault’s painting—Pierre, who came later, said the same thing as soon as he saw it. I am proud of Baltusz, René, he’ll be a great painter, you’ll see; as you know, he’s copying Narcisse.… I’m ecstatic about Poussin’s picture, can’t stop marveling at the mastery and the expression of each brushstroke. Actually, one can’t be sure it’s actually painted, but perhaps breathed by some god; the same kind of enchantment produced by pure music. The lips already dead utter divine words.11

Balthus finished the work just after Christmas. He inscribed it in the rock: “A René.” Baladine immediately wrote the intended recipient; “My dear René, this copy is a wonder as both matter and spirit, as you will see.”12 She continued to effuse in letter after letter.

Even before he took possession of the work, Rilke wrote Balthus, who was about to turn eighteen, “This Narcisse makes me proud and happy that it will eventually come to enrich my immediate surroundings with its composite tenderness and with that admiring summa to which it testifies.” On the other hand, because of the importance of the copy, he wanted Balthus to take his time sending it.

But first it must stay with you so that you can show it to the friends of your friends, and also so that by seeing it more you will be inspired with the will to make other splendors according to the old masters or according to the harmony established between your imagination and whatever happens to you in life.

Nothing could have been more fitting than for Balthus to paint Echo et Narcisse as a gift to Rainer Maria Rilke. For in January 1925 Rilke had written the poem “Narcisse,” which he dedicated to Balthus.

Encircled by her arms as by a shell,

she hears her being murmur,

while forever he endures

the outrage of his too pure image.…

Wistfully following their example,

nature re-enters herself;

contemplating its own sap, the flower

becomes too soft, and the boulder hardens.…

It’s the return of all desire that enters

toward all life embracing itself from afar.…

Where does it fall? Under the dwindling

surface, does it hope to renew a center?13

Narcissus, at the time of the events chronicled in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and alluded to by Rilke, was sixteen: Balthus’s exact age. Ovid had described the youth destroyed by self-love as

Enchanted by the charms which were his own.

Himself the worshiped and the worshiper.14

BALTHUS PRESIDING OVER grand dinners at the Villa Medici, using Le Figaro to disseminate chosen details about himself to an eager public, keeping the world at a precisely calibrated distance: Ovid’s words were an apt prediction of his dedicatee’s future life.

As for Echo—the woman who could initiate no sounds, but could only repeat what she heard from others; who ended up betrayed by Narcissus, vanished in the forest as a disembodied echo: isn’t this the role to which Rilke’s young friend would perpetually relegate those who tried to get close?

THE NARCISSUS MYTH is not only a parable of self-worship, and of the concomitant exclusion of the other people in one’s orbit. It is also an evocation of the way in which vision—both optical and psychological—is constantly fleeting. Narcissus’s attempt to embrace his image in the well is like the little boy’s efforts to hold on to Mitsou, and Balthus’s later attempt to evoke the seeable world in paint on canvas:

O foolish innocent! Why try to grasp at shadows in their flight? What he had tried to hold resided nowhere.

Narcissus’s cry—“I am entranced, enchanted / By what I see, yet it eludes me, error or hope becomes the thing I love”—could have been, at almost any point in his life, Balthus’s unspoken lament, whether his focus was on himself or on the world beyond.

In Ovid, metamorphosis is perpetual. Rilke’s poem thus focuses on transformations—of the boy into a flower, and of Echo into stone. Balthus would similarly shift realities as he altered personas, and invoke the ongoing process of appearance and disappearance in his art. Rilke’s “dwindling surface” describes the still lifes, urban scenes, and portraits Balthus painted for decades after Rilke dedicated these words to him.

His bathers have only a moment ago stepped out of the tub, as if in the process of birth. His peaches and apples have just ascended to their peak of ripeness—and are also on the very verge of withering. People in The Passage (1952–54) move from shop to home; they are between places more than at places. All that is certain is change and flux; the cycle of diminishment and emergence is continuous.

Rilke’s poem has the sense of gain and loss that would underlie Balthus’s painstaking process of painting and repainting a single work over a period of years. The surface dwindles; the center is renewed. Trying to capture the essence of what is there before our eyes in the Rotterdam Card Players, Balthus added so much paint that the unframed canvas weighs four hundred pounds.

IN A LETTER THAT RILKE WROTE to Balthus primarily to extol the merits of the Narcisse copy, the poet dwelt further on the matter of how little we can know or apprehend. Balthus’s eighteenth birthday, or lack thereof, only a few days away, provided the perfect starting point. The date was February 24, 1926:

Once again, my dear B.…, you must organize a little festivity for yourself with the eleven imperceptible intervals between the strokes of midnight on February 28. Few persons, certainly, possess such pure, such untouched material with which to compose their birthday; yours, rare as it is, is a true collector’s item. Make for yourself, therefore, out of the minuscule elements of its absence a lovely personal substance on which other people, on the morning of March 1, can rest their eyes and their good wishes. And may the new year be useful and usable for your deepest needs, known or unknown to yourself.

To be someone who has no need to pin everything down gives one a certain nobility. The recipient of that letter was in complete agreement that atmosphere and personal preference outweighed the tedious notion of irrefutable facts. Fealty to his own shifting fantasies would suit him far more than enslavement to reality.

IN MY DAYS AND NIGHTS with Balthus in Rossinière, his dark eyes sparkled especially on the many occasions when we discussed literary fiction. Toward the end of our long lunches in the spacious dining room, or in front of the fire in the library after dinner, the artist would recite Poe with daunting accuracy and recount Chinese folktales in splendid detail. He spoke of characters in nineteenth-century novels as if they were the most real people of all. The personalities conjured by Stendhal and Chateaubriand were his close acquaintances.

At those moments he always sat still, in rapt concentration; he seemed far more comfortable than when the subject was either his own past or his art. The realm of imagination—a world that could be constructed from kernels of truth leavened by fantasy and invention—was where he was most at home.

At age sixteen, contemplating Poussin’s and Rilke’s images of the dying Narcissus giving birth to the flower and of Echo turning into a rock, he was equally centered. The lack of plausibility gave him no trouble. Explanations for the scene or its ramifications were beside the point. Part of the majesty of art comes from its power to transform, to create sights and forms of perception that never existed before. Facts are not the issue. Rather than engage in the tiresome, and futile, attempt to capture and impale truth, no more attainable than a missing cat, one should succumb to the enchanting spell of the made-up.

IN THE SPRING OF 1926, Balthus made a copy of Poussin’s Concert. He was schooling himself intensely in French art. At the same time, Claude Lorrain, David, Ingres, Delacroix, and Théodore Géricault begin to exert their lifelong influence on him. Géricault had been the subject of a major exhibition at the Galerie Charpentier on the centennial of his death in 1924, the year of Balthus’s arrival in Paris. The fierce romanticism of this “maudit”—that category of artists distinguished as thrillingly “damned”—his captivating imagery, and his marvelous ability with paint wooed its eager young viewer. Géricault, too, had mastered the craft of painting by copying Poussin in his own independent way; at least one such study was in the Charpentier show. That exhibition also had in it Portrait of Louise Vernet as a Child, called Child with a Cat as well, a painting of the daughter of the painter Horace Vernet. This marvelous canvas depicts a child not yet ten years old but surprisingly womanly with her mature pose and Empire dress. Mademoiselle Vernet, transfixed in a sort of reverie, holds a knowing, sphinxlike cat on her lap. She seems very much the predecessor of Balthus’s paintings of Thérèse done when Balthus was living back in Paris fourteen years later—in 1938, the same year this painting passed permanently from the estate of Madame Philippe Delaroche-Vernet into the collection of the Louvre.

Jean-Louis-André-Théodore Géricault, Portrait of Louise Vernet as a Child (also called Child with a Cat), c. 1822, oil on canvas, 60.5 × 50.5 cm (photo credit 5.3)

Géricault was a stirring mentor: for the sheer assurance and authority with which he worked, and for the virility and completeness of his painting. Each work presented dramatic subject matter in a rhythmic, engaging way.

Yet for the art Balthus now wanted to imbibe, Paris was no longer the answer. The time had come to go to Italy.