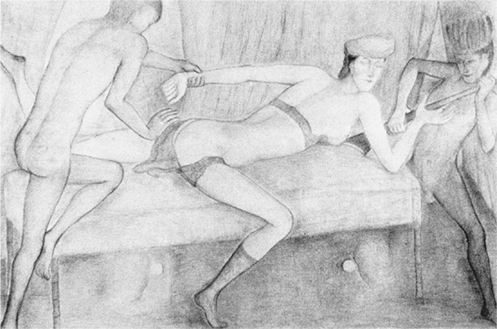

Study after “The Guitar Lesson,” 1949, ink, 28.5 × 19.1 cm (photo credit 10.1)

To accomplish the tour de force in its entirety, it remained for the author only to divest himself (as much as possible) of his sex, and to make himself a woman. This resulted in a marvel; for, in spite of all his zeal as an actor, [Flaubert] could not but infuse his virile blood into the veins of his creation, and Madame Bovary, for what there is in her that is the most forceful and the most ambitious, and also the most of a dreamer, remained a man.

—BAUDELAIRE1

I believed, from the time I could reason, that nature and fortune had joined together to heap their gifts upon me; I believed it because people were foolish enough to tell me so, and this ridiculous prejudice made me haughty, despotic, and angry. It seemed that everything must give in to me, that the whole world must flatter my whims, and that it was up to me alone to conceive and satisfy them.

—MARQUIS DE SADE2

ANOTHER OF THE PAINTINGS in Balthus’s 1934 Galerie Pierre exhibition which James Thrall Soby brought to America was ultimately deemed too scandalous to hang at as allegedly enlightened an institution as the Museum of Modern Art. But unlike The Street, it could not merely have one salacious passage repainted so that it might be shown publicly. Even in the libertine 1980s, Balthus’s painting was considered so immoral that censorship prevailed and the public was denied access to it forever. The painting was The Guitar Lesson (color plate 5).

The imaginative fantasy on flagrant display in this large canvas was an original and cruel scenario that linked sex and violence inexorably, in a seemingly safe and well-appointed bourgeois sitting room. The Guitar Lesson shows a stormy sexual encounter between a dominating, tyrannical woman—she seems to be in her twenties—and a girl about twelve years old, whom the older creature is sadistically inducting into the life of flesh. The child appears stunned but not entirely unhappy. Both of the players are lost in the glories of all-consuming, obsessive passion.

A music lesson has just been interrupted. A guitar is lying on the floor. The woman has thrown the girl across her lap and yanked her dress up over her navel. The child is naked from navel to knees, while her lower legs are covered in high socks. With her right hand, the ferocious instructress pulls back a clump of her victim’s long, flowing hair. The pain must be excruciating. The older woman digs the fingers of her left hand—which look like talons—into the upper part of the girl’s inner thigh, just below the child’s bulging vulva.

With her left hand, the pupil has grabbed the teacher’s silky gray dress by the neckline just below the ample bosom that is in such marked contrast to her own undeveloped chest. Exactly like the women in two of the other paintings in the Galerie Pierre show, the instructress is in Balthus’s favorite pose of one breast exposed, the other covered. The bare one is taut and muscular. An erect nipple juts out from it at a high angle. It is more like a weapon than a source of nourishment. Because of the extent of exposure, the painting resembles a Madonna, but this is a mockery of the Virgin.

The Guitar Lesson is, in fact, a neat blend of Madonna and Lamentation: an erudite, modern-dress, erotic version of Renaissance prototypes. It hearkens back to classic renderings of both the beginning and the end. At the same time, it is a laden sexual encounter. It invests that traditional imagery with the most rabid human cravings and gives unabashed sadomasochism a vivid life virtually unprecedented in the history of art.

Today we enjoy the freedom to read, read most anything, whether by a literary master or by a hack with a flair for using “dirty” words. Even the cinema permits us to observe couples performing the sex act. When it comes to sculpture and painting however there is still an aura of the forbidden connected with presenting them to the public. Monarchs, aristocrats and millionaires have always had access to these forbidden treasures of art. So has the Church and State. To be sure, these collections are not at the disposal of the general public.… The strange thing is that, so far as we know, none of the keepers of this unholy assortment of art has ever run amuck, has never become a rapist or a degenerate, which is alleged might happen to the man in the street were he exposed to such works. The rich collector, the expert, the critic of art, the clergy, the censors might view such work without fear of moral derangement, but not the ordinary man. L’homme moyen was regarded as a potential sex maniac who had to be hedged in with all manner of restrictive prohibitions.

—HENRY MILLER3

WHEN The Guitar Lesson WAS shown at Pierre Loeb’s gallery, its twenty-six-year-old creator had conspired with Loeb to hang the painting behind a covering in the back room of the gallery, like an elegant peep show for selected eyes only. Then, several years following this clandestine presentation at Loeb’s, James Thrall Soby acquired The Guitar Lesson from the Paris dealer Pierre Colle. If The Street was too risqué for visitors even in the privacy of Soby’s Connecticut living room, this new painting had to be held under tighter wraps. The Guitar Lesson was never shown with the rest of Soby’s collection at Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum and other locations, and its owner eliminated it completely from his writing on Balthus.

Soby saw the painting only in his storage vault. After a while there was no point in owning it. In April 1945, about seven years after he acquired this extraordinary canvas, the collector, courageous as he was, swapped it with the painter Roberto Matta Echaurren for one of Matta’s own works. When, a few years later, Matta’s ex-wife married Pierre Matisse, The Guitar Lesson became part of the gallery’s collection. It remained there, in private storage, seen by virtually no one, until the late 1970s. Its existence was known to Balthus aficionados—who had either seen it in 1934 or at least gotten wind of it and the furor it caused—but hardly anyone ever viewed the actual work or knew its whereabouts.

Then, in 1977, Pierre Matisse presented it to the public during a Balthus exhibition—much awaited, the first after a ten-year hiatus—at his New York gallery. The painting was the talk of New York. For one month, throngs of people—the majority of them students and young artists—crowded into the small exhibition space on Fifty-seventh Street. The area in front of The Guitar Lesson was always thick with viewers. This, above all, was the work people had come to see.

Hilton Kramer told me that when he asked Pierre Matisse if it wasn’t gratifying to have students always congregating in front of the canvas, Matisse replied that the difficulty was in getting them to leave the gallery at closing time. But in any event, they were all there the next morning waiting for the gallery to reopen. The Guitar Lesson exerted a virtually unprecedented magnetic attraction on the viewing public.

Having clearly anticipated that it would be the pièce de résistance, Pierre Matisse had The Guitar Lesson as the full-color frontispiece of the exhibition catalog—the first time it had ever been reproduced. Opposite the riveting, disturbing image, there was an essay by the film director Federico Fellini, which was translated by Luigi Barzini.

Fellini had been one of Balthus’s regular visitors and close friends in the Villa Medici period. The juxtaposition of his text with the reproduction of that stunning painting is pure Balthus. The essay reads more as if it were written by an elderly Roman history professor than by the maker of La dolce vita and 8½. You might expect Fellini’s commentary to be fluent and spicy; on the contrary, it is measured to the utmost, almost impenetrably vague, and exceedingly high-toned.

The implication is clear, and perfectly in accord with the wishes of the Balthus of 1977—in contrast to the troublemaker of 1934. The goal was no longer to shock the bourgeoisie. Instead, Fellini acted as a spokesman for the Count de Rola. Rather than dwell on the androgynous seductress strumming the inner thighs of her exposed, ecstatic victim, Fellini steers toward spheres supposedly loftier than the realm of sexual urges.

The director focuses first on “the feeling for that accumulation of history that is Balthus,” declaring that “history is no longer for him an objective and indifferent catalog, but is rather present, alive, and renews itself in a time that is only to be found in his conscience.” We feel that Balthus is, above all, the calculator and craftsman, the artist and organizer with a distinct agenda and the dexterity to realize it. Indeed, he is the equivalent of the seductive teacher in The Guitar Lesson—served perfectly by his friend Fellini’s words:

Every image is the result of the patient search for “that” form; the irreplaceable caliber of that form, the exact and unalterable tone of a color are obtained, one would say, by cutting away from the material, with delicate scalpels, the veils which still alter the balance that the author already perceives in its entirety and is trying to reach by degrees.4

Fellini’s commentary ignores the real-life context of the painting and focuses only on the formal, but the meticulous know-how he attributes to Balthus the painter is clearly akin to that of the enthralled, enthralling music teacher.

AT THE TIME OF THE EXHIBITION at Pierre Matisse’s, numerous magazine and newspaper reviews referred to the canvas. But none dared show it. The critics explained that the shock would be too great. The distinguished Thomas Hess devoted most of his Balthus article in New York magazine to a brilliant and insightful description of the painting, but explained, without giving any further reason, “I dwell at some length on The Guitar Lesson, even though it can’t be illustrated in the pages of New York.”5 Clearly this was more than even a supposedly sophisticated audience could handle.

Then, the year following that first presentation of The Guitar Lesson in his gallery, Pierre Matisse tried to donate it to the Museum of Modern Art. Given the attention the initiation scene had generated during its singular public showing a few months earlier, its owner was thoughtful and generous in subsequently trying to make it available to the public at all times. He wished it to be a memorial to his late wife, Patricia. This was intended as a monumental tribute: to a woman he wanted to honor, to an artist he had loyally represented for almost forty years, and to the recipient institution—a museum that had both done great honor to his father and recognizably improved the experience of living in New York. Pierre Matisse, who had a large collection of work by a range of major modern painters, had deliberately selected one of his masterpieces.

Blanchette Rockefeller—Mrs. John D. III—who was then chairman of the board at MoMA, did not approve, however, when she saw the painting at a small presentation of Pierre Matisse’s recent gifts to the museum. Even in a place where Picasso’s vagina dentata hangs unchallenged and Amedeo Modigliani’s and Gaston Lachaise’s forthright interpretations of the nude body are boldly exhibited, The Guitar Lesson was declared to be too obscene and sacrilegious to be displayed. Blanchette Rockefeller could sanction no such immorality. Having kept Balthus’s painting in storage for almost five years, MoMA returned it to its unsuccessful would-be donor in 1982.

IN THE WAKE OF THE SO-CALLED sexual revolution, Americans have become increasingly hysterical about the issue of children and sex. If Balthus has not only come to feel alienated by the vulgarity of American interior decoration but also become paranoiac about the national attitude toward anything suggestive of children’s sexuality in art, he has good reason to feel fearful. If Mrs. Rockefeller’s power was extraordinary, her attitude was symptomatic. In 1994 a respectable New Jersey businessman who was taking a course at the International Center of Photography shot, in a single fifteen-minute session, a series of images of his six-year-old daughter in the nude. The photo-processing lab reported this to the authorities, and the man’s three children were rushed to the police station, where they were interrogated “about good touches and bad [and] the existence of God.” Their father was handcuffed, jailed, “and ever after that forbidden further contact with the daughter he had photographed.”6 It was almost a year before the man could prevail against the state and obtain permission to return home.

Such incidents are directly related to the fate that has befallen one of the greatest paintings of our century. In a less censorious world, Balthus might not have been driven repeatedly to say that he wished he had never painted The Guitar Lesson. But with his antennae for public taste and his wish to avoid further opprobrium, he kept the work out of his Pompidou-Metropolitan retrospective, and has assured its isolation for years to come. What the public has lost is a painting as brave and brilliant in its artistic technique as in its narrative.

WHEN The Guitar Lesson WAS notably absent from Balthus’s Centre Pompidou retrospective in 1983–84, Le Monde explained that the painting was missing at the insistence of the artist, who considered it “an initiatory painting reserved for the eyes of a small elite.” Dominique Bozo, the museum director, lamented in the catalog that two essential canvases that they had hoped would be in the show were not there, the other one besides The Guitar Lesson being The Room of 1952–54.

The Centre Pompidou director went to great lengths, odd for an exhibition organizer, to point out to his public how deprived they were:

The Guitar Lesson too, for reasons which we do not entirely share, reveals fifty years after it was painted, how much Balthus’s work still disturbs and profoundly troubles us today. First shown in 1934 at Pierre Loeb’s gallery, but not in the gallery’s main exhibition space, it reappeared in public only in 1977 at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York. Anglo-Saxon puritanism then obliged Tom Hess to apologize for being unable to reproduce the painting in his article in New York, though only after a long and exact description: “I dwell at some length on The Guitar Lesson, even though it can’t be illustrated in the pages of New York, because of the intensity of its image.” This canvas, which Balthus actually regards as initiatory and which was doubtless intended only for certain “privileged viewers, in secrecy” and was perhaps prematurely subjected to the gaze of the public at large, recently suffered a misfortune which has “obliged the painter to prevent its divulgation”! Its reappearance, then, must occur at some future date. Yet it seemed to us, seeing it again quite recently, that this highly charged image, sustained as it is by an exceptional plastic quality, is obviously one of the great classics of the twentieth century. It is with enormous sadness that we have had to forgo its presence here, for it seemed to us that the painting, as one discovered when confronted by the actual canvas, if not independent of the image, does suppress the possible misunderstanding of the reproduction and in fact ensures its disturbing coherence.7

While emphasizing the significance of the loss, Bozo provides no satisfactory reasons for the absence of the pivotal canvas. The museum director exercises a Balthusian elusiveness about the omission. He establishes that The Guitar Lesson has been excluded because the painter himself inveighed against its presence, but one is at a loss to know what the mechanics of this deliberate self-censorship were.

Balthus, after all, no longer owned The Guitar Lesson. Its owner was a free agent. But who was the owner at that point? Had Balthus instructed this person not to lend it? If so, why was the painter against its inclusion? Why would the owner comply? And what, precisely, was the forbidden fruit?

In his comments, Bozo implicitly blames American taste for the predicament to which the more enlightened French were now subjected. Bozo was right; if the Museum of Modern Art had accepted The Guitar Lesson, it would have been able to lend the painting.

Of course, Bozo, while alluding to the restrictions on New York magazine, diplomatically avoids making any specific reference to MoMA. The French museum director would not have risked antagonizing the administration of an institution with which he needed to collaborate regularly. Officials at MoMA probably would have been highly embarrassed to let it be known that pressure from one rich trustee had prevented their acquisition of this extraordinary Balthus painting.

Bozo also avoids stating that the person exercising the ultimate control was, as usual, Balthus. Just a few years earlier, Pierre Matisse had had Balthus’s go-ahead on the presentation to MoMA. Still the owner, Matisse would inevitably have followed Balthus’s instructions with respect to the Pompidou. Yet again, it was the artist himself who chose to keep The Guitar Lesson under wraps.

ONE MIGHT SAY THAT the exhibition organizers and Pierre Matisse were properly honoring an artist’s rights.

Yet to listen to Balthus, the authorities at the Centre Pompidou failed to do him justice. Balthus complained to me that the Parisian curators were oblivious to his way of seeing. The Pompidou lighting was disastrous. In our conversation one day, his paintings were “murdered”; the next day they were “slaughtered.” Balthus only painted in the natural luminosity of daylight; the glare of spotlights obliterated the subtle tonality he had painstakingly achieved. The Centre Pompidou was, he said, a “horrible place, horrible place.” He termed his show there “a massacre, absolutely killing everything. All those relationships of color killed by electric light. You couldn’t see The Passage du Commerce at all, there was such a strong light on top, with all the rest in the dark. The way people look at painting now is so surprising and so strange that sometimes one asks oneself whether it’s worth showing paintings.”

He continued, “Paintings shouldn’t be seen in electric light. The first paintings I saw in electric light were in Paris, probably 1925. A Cézanne show at the Salle Pleyel—toward the Bois [de Boulogne]. There was an art gallery in the same building, a sous-sol, and I saw for the first time Cézanne with electric light, and they looked like reproductions.”

Balthus also generally detested the architecture of the galleries in which the work was installed in Paris. If on one level Bozo had generously honored his wishes, on the essential issue of visual presentation the museum director had let the artist down brutally.

IF BALTHUS BELIEVED, first and foremost, that he should be judged not for his subject matter but for his ability to paint, he did himself an enormous disservice by excluding what is arguably the greatest evidence of his technical virtuosity. To prevent its being seen was an act of petulance—MoMA had turned it down; therefore the public did not deserve to see it—that worked against the artist’s own interests. Balthus must have known that hordes of Parisians, like those crowds that stood four or five people deep at all hours in 1977 at Pierre Matisse’s, would have loved the canvas. It is as if he was punishing the world, and himself, because of Blanchette Rockefeller and her cronies.

On the other hand, Balthus may by this time have wanted to stay clear of scandal as assiduously as he had once sought it. Maybe the Count de Rola didn’t want the parents of the other children at his daughter’s Swiss school tittering. So he willingly succumbed to the dictates of the bourgeois establishment he had once deliberately offended.

As always, he had a story and a reason for his actions. What Balthus insisted to me is that the explicitly sexual side of his art causes people to focus on the wrong things. Yet as a former model of Balthus’s—an old friend who knew him well—pointed out to me, the real danger of The Guitar Lesson is that it lays the truth bare. This very beautiful, stirring painting lacks the convenient cloak of hazy ambiguity. Everything is visible, clear as day. This, more than anything, was what the Count de Rola wished to avoid.

…

DOMINIQUE BOZO’S PREDICTIONS of the future reappearance of The Guitar Lesson are unlikely to come true. The 1977 Pierre Matisse Gallery show was, in all likelihood, not only the first but also the last time the painting will ever be seen by more than a few individuals. That month will probably be the only occasion in any of our lifetimes when The Guitar Lesson might be viewed other than by private invitation.

A couple of years after its return from MoMA, Pierre Matisse sold the painting to the film actor-director Mike Nichols. Tana Matisse, Pierre’s widow—his third wife from a late marriage, forty years his junior, the diligent keeper of his flame—provided this history for me. Than, in the late 1980s, when the prices for Balthus’s paintings had gone higher than ever before, Nichols sold The Guitar Lesson through the Zurich gallery Thomas Ammann. Ammann soon resold it to a person of vast wealth who keeps it privately and intends never to sell or lend it. And so today The Guitar Lesson—the extraordinary painting that might have belonged to a major public museum had it not been for the censorship of one influential trustee—is virtually off the map.

One of the few other paintings to be treated as such was Courbet’s 1866 Birth of the World—a graphic and exquisitely painted between-the-knees view of female genitalia. The original owner of the painting, the Turkish diplomat Khalil Bey, had always kept it cloaked much as The Guitar Lesson was at Pierre Loeb’s gallery. But the Courbet then became the possession of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan—whom Balthus knew, and in whose collection he would have seen it uncovered. And now it belongs to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it is shown freely.

The Courbet is out there, and the secret chambers at Pompeii have been unlocked. But Balthus’s canvas is unique in the extent to which it has been held captive. Having almost consistently been kept off limits to the world at large, now—even if its prison is known—it will probably remain in hiding forever.

THE FIRST TIME THIS “initiatory” canvas came up in our discussion, Balthus told me that he had no idea where it was or who owned it. But two days later, once he had apparently become more comfortable with me, he allowed he had heard various rumors of its whereabouts. Squinting his eyes, he strained to remember. Oh yes, it had been for sale in Switzerland, after “some film person” owned it—he could not, however, remember the name. I suggested Mike Nichols; I did not yet know that this was the case, but I knew Nichols owned other of Balthus’s paintings, including a splendid version of The Three Sisters, and I could imagine him owning The Guitar Lesson as well. Balthus looked quizzical and merely asked if there weren’t “also a Nicholson.”

In our next conversation about The Guitar Lesson, however, the artist recalled quite a bit more. He allowed that the canvas might now belong to a Greek shipping magnate. But who knew in which residence the wealthy Greek had it? And perhaps by now it had gone somewhere else; he was not sure.

Then, one morning toward the end of my second visit to him, Balthus named the owner of The Guitar Lesson. He wore an expression of unequaled delight as he let the elegant appellation roll off his tongue and slowly enunciated its mellifluous syllables. Balthus was patently thrilled to play a part in this international tycoon’s world. What a coup that this painting he had made when he could scarcely afford the rent on his one-room studio was now treasured by someone of such prominence.

But I must never let on that I knew. The collector’s name had to be kept private, Balthus told me. This idea that the information was clandestine enchanted Balthus almost as much as the billionaire’s stature.

Citing the location of the painting as the lair of someone as secretive and powerful as an Ian Fleming character, Balthus had his little-boy look of glee. It was a fine solution after the abuse of those hand-wringers and culture vultures at MoMA.

THE FLEMING COMPARISON is mine, but I thought of it because Balthus proudly told me that he was a friend of the “terribly amusing” Fleming in the 1930s. Moreover, he was a tremendous fan of all the James Bond books. Now he had made it sound as if The Guitar Lesson belonged to Dr. No.

The painting’s seclusion and inaccessibility rather delighted its maker. Balthus, after all, had insisted on its initially being viewed only by the select few in the back room at Pierre Loeb’s. Besides asserting that he wished he had never painted the canvas to begin with, he repeatedly claimed to me that although The Guitar Lesson was nothing more than the sort of thing you do when you are young and intend provocation, it has led to major misunderstandings about his work. So why not keep it out of bounds to the public at large? This was a better proposition than having the painting displayed in an artificially lit museum space where ignorant audiences would make lots of irritating remarks.

Yet at other moments Balthus was highly annoyed that The Guitar Lesson had escaped his grasp. Its fate was typical of the wounds inflicted on artists by the art world—according to Balthus’s construction, yet again, of his own victimization. Here, too, the artist was presenting himself as the earnest and naive good guy of whom cannier people took unfair advantage. It was like his depiction of Pierre Loeb’s alleged maneuvers with Joan Miró and His Daughter Dolores (a sequence of events that I had subsequently come to believe had not actually occurred as Balthus had described it). He told the tale in a way meant to show how an artist could lose control of his own work, how paintings could become a commodity in a way that had nothing to do with their creator.

Then Balthus would resign himself to these events and become philosophical about them. Disappearance is inevitable, he reminded me. Consider what happened to Mitsou, and to that canvas that fell off the car roof.

AFTER MY SECOND STAY with Balthus, Tana Matisse made the initial steps necessary for me to see The Guitar Lesson. Balthus must have authorized this and given me the equivalent of security clearance. As with my initial visit to Le Grand Chalet, I was welcomed into a private and secret universe.

The arrangements for my actual visitation with the hidden painting had the ring of adventure and intrigue. I felt as if I were organizing the transfer of hot loot with gangsters. Mrs. Matisse told me that I had to understand that, in deference to both Balthus’s and the owner’s wishes, I could pass on the information about the whereabouts of The Guitar Lesson to no one whatsoever. I should not even cite the city.

Yet once the secrecy was established, I was treated like royalty. I phoned the owner’s office as instructed and reached the designated business assistant, who explained that I would be met at the owner’s residence. We settled on a mutually convenient time, and I was assured that I could have as long as I liked with the work.

WHEN THE APPOINTED DAY CAME, I entered a mythic world. In 1934 the back room that housed the painting was a tiny space behind a small gallery. Half a century later, The Guitar Lesson has ended up in a secret domain of unfathomable opulence. Its present place of hiding is as different from its original lair as Le Grand Chalet is from the garret on the Rue de Fürstemberg.

As the gates lifted for my visitation, it struck me that the painting in its current situation is like Balthus himself. It is extremely secure and protected. It abides in reclusive luxury. It belongs to the top echelon of society, the world of those who know both how to attract the spotlight and how to avoid it. It lives like rare, forbidden fruit. It may be visited by the select few, but by the time you are in its hiding place, you feel as if you are having an audience with royalty and are ignited by the mere act of gaining access.

The doorman was expecting me at the address I had been given for a vast flat in the heart of one of the finest residential districts in one of the largest cities in the world. The elevator doors opened onto a vestibule from which I reached a dark entrance hall the size of a small ballroom. I was met there by the owner’s employee, an amiable fellow in a dark suit, who quickly led me off to the left, but even at our rapid pace I took in the otherworldly figures looming from a large El Greco. The man guided me down several corridors that were practically the length of theater aisles. Doors on both sides revealed multiple chambers in which I glimpsed French furniture, Courbets, some well-known Cézannes, a large early Matisse I had often seen lent anonymously in major exhibitions, and old masters. Heading beyond them, I felt as if I were going to see the most secret treasure in the trove.

We finally arrived at an elaborately paneled bedroom, furnished like rooms at Versailles. Under the coffered ceiling, Balthus’s “initiative” canvas hung in the sleeping alcove. Like a piece of erotica, it is displayed alone on a wall so it can easily be viewed from the large bed canopied in stiff brocade. If one were on one’s back on that splendid bed, the painting would be to the right. On the opposite side, large windows—framed by heavy draperies, tasseled and fringed—look out on a spectacular urban vista. The Modigliani portrait between those windows seems to have been induced into its drugged stupor by The Guitar Lesson across the way.

This private chamber of the exotic potentate—I knew, after all, who my Dr. No was, even if I could divulge the name to no one—was not, however, without its mundane touches. Next to the lavish Louis XIV bed, on the delicate marquetry table, stood, in plain view, a king-size container of Preparation H. It was almost as large as the delicate base of the porcelain lamp next to it. And at the foot of the bed there was a VCR on a scale generally found in bars packed with sports fans. I imagined a film version of The Guitar Lesson, directed by a master of pornography and starring skilled sybarites, being shown on it.

The owner’s employee told me to sit on the bed and take as much time as I wished studying the painting. I could have asked for no better circumstances to be before the sacred altar. A butler arrived with a silver tray and served me a large, steaming cappuccino topped with bittersweet chocolate shavings. Perhaps all artistic masterpieces should be kept this way; it certainly beat the usual frantic search for 500-lire coins to drop into a machine for a few minutes of poor light on a Renaissance masterpiece in a cold and damp Italian church. For two hours, in perfect comfort, I studied Balthus’s masterpiece and took notes.

FOR SEVERAL YEARS, on the infrequent occasions when I mentioned my magical audience with The Guitar Lesson to anyone, I honored the terms of secrecy of the visitation. I planned to write about the painting without ever saying where it was—even what city it was in. I knew, after all, that the billionaire owner of this once unsalable masterpiece of erotica had residences in Paris, New York, and London (a penthouse at Claridge’s), as well as Villefranche and Saint-Moritz, and a yacht he kept in the Aegean. For all I knew, he moved it from place to place—or took it wherever he went, like a portable altarpiece.

There was, I must admit, something nice about this feeling of being an insider, and I relished my complicity. It was much the way I felt when I first interviewed Balthus and thought, like all of his interviewers, that he was talking to me when he would not do so to others.

I felt duped therefore, when, having kept my word about not revealing where Balthus’s early masterpiece was (and probably antagonizing a couple of friends by not revealing its location), the allegedly never-to-be-known information appeared in a 1994 New York Times Magazine article on Balthus. This was yet another of the many pieces where the author acted as if the reclusive artist had at last granted a rare interview. Whether Ted Morgan, who wrote the article, had breached a promise by divulging this information about The Guitar Lesson, or whether yesterday’s top secret was today’s common knowledge, I could not be sure, but I felt foolish and undermined. Now any reader of the Sunday Times might learn that the salacious canvas was in the New York apartment of Stavros Niarchos. The fact is not of vast significance, but in guarding it so carefully, I seem to have been as controlled, as held in thrall, as the child in the painting.

“I bargained for humiliation,” she said. “If I had to choose between unhumiliated boredom and humiliated fulfillment, even for a short time, I took the latter. I had no illusions about him; I expected to be smacked and brutalized, but it is his aura that takes me to bed, to sofa, to the kitchen table, not a man. I find myself possessed by a notorious whirlwind so heedless that it cares not what it leaves behind. It is not pleasure he takes with me, but proof.”

—PAUL WEST, Lord Byron’s Daughter8

THE GIRL IN The Guitar Lesson hangs, with her left hand, from the neckline of the teacher’s dress. In doing so, she turns the gray satin of the low-cut, old-fashioned garment into a sort of sling that cradles the older woman’s excited breast. Is this child grabbing the fabric to brace herself? A desperate attempt to keep from falling?

Or has she deliberately denuded that breast out of lust? Would she like to finger the teacher’s erect nipple? Has she been forced to straddle the woman’s lap, or is she there by choice?

The scenario offers multiple readings. Perhaps the teacher is an unabashed seductress, the pupil a hapless victim holding on for dear life. Or maybe the girl is stripping the teacher out of clear and conscious longing. The way her right hand falls to the ground suggests that she is helpless; by using her left hand to hold back the teacher’s dress and practically tweaking the erect nipple of the mature instructress’s bulging right breast, she also participates enthusiastically.

In either case, confronted by that angular peak of a bosom, the young initiate is stunned. The child is overwhelmed both by this organ that represents her own future, that embodies her own incipient sexuality and the womanliness that awaits her, and by the sensation the teacher is inducing high within the girl’s inner thigh.

The girl responds to the violent pulling of her hair and the invasive gouging of her thigh with both rapture and anguish. Balthus has seen to it that the specifics of her emotions are inaccessible. Wearing almost the identical outfit as the creature under attack in The Street, she is in a similarly disconnected state. She is dazed: somewhere between misery and ecstasy. Like her twin in The Street, she appears alarmed but anesthetized.

The teacher, too, is a conflux of emotions. Her face mixes rapture with scorn. While she eagerly contemplates her prey, she is entirely self-absorbed. Is the scene an act of punishment? Is the teacher seducing the girl or chastising her? Is this retribution for the child’s sexual impulses; has the older woman taken violent action against the younger one because, a moment beforehand, the child attempted to touch the woman’s breast and is still trying to do so? Is the teacher gleefully introducing her protégée to a world of violent pleasure? Whether the instructress is contentedly forcing and inspiring the child’s action—or, with equal pleasure, inflicting pain on her for it—is ambiguous.

THE MOTIVES AND FEELINGS are hazy, but in plastic values, the scene could not be clearer. The two bodies have been stretched to the utmost. The girl’s torso is pulled as if on a rack—so that her pelvic bone is pushed upward, her pudenda thrust forward, her thigh stretched to the breaking point. Only her right arm and her hair lie limp. Balthus has fixed the locking figures in position, sharpening it all with his precise use of light and dark.

The teacher evades us, but not herself; she knows precisely what she is doing. Whatever the exact sequence of events here, the older woman is control itself. She manipulates the child with the authority of an expert worker of marionettes, holding the girl’s hair and thigh just so. She has experience; she has probably given this sort of lesson before.

She uses her charms to full effect. Possessed of the elegance of a Boucher nymph—and dressed with marvelous style in her coquettish dress, of the shepherdess mode an eighteenth-century courtesan might have worn to a country dance—she is a stunning demon. Her stylish looks add panache to her diabolical squint. Moreover, the woman has tremendous physical strength. She is built like a monster. Her oversized arms have the grip of steel vises. Her strong legs lock firmly into place underneath the girl. To exert maximal force, she twists herself like a coiled spring. Her powerful torso in its sculptural contrapposto interlocked with that of the passive, dazed, limp child make a dynamic, galvanic pairing—like Bernini’s Rape of Persephone or Daphne and Apollo.

Strong as her body is, it is the teacher’s face that dominates the painting. Her large head with its mass of hair has the same width as her shoulders; the addition of her hair brings it out to the shoulders’ dimensions completely. These proportions—typical for Balthus’s work, but even more pronounced here—lead us to concentrate on the protagonist’s face. The huge scale of people’s heads makes it seem that their bodies are what they are and do what they do in response to the mind. The cerebral dictates the physical. All the gripping and grabbing and posing are the result of precise mental calculation. The sadism is carefully thought-out.

AS WITH The Street, IN The Guitar Lesson it is as if time has suddenly been frozen. This is an in-between moment—like the “Crac” between midnight of February 28 and the start of March 1 about which Rilke wrote to the young Balthus at the time of his nonexistent birthdays. The occasion exists more in imagination than in fact. The reality of the present eludes us; we more readily grasp what has previously taken place and what will soon occur. While the details of the current scene beg many questions, we apprehend without difficulty the lesson that was interrupted by rage and lust, and the possibility of ecstatic lovemaking to follow.

Yet Balthus has painted the imaginary interlude so brilliantly that the stormy scene has the superreality of a dream image. It is as palpable as it is ambiguous. The concentrated and isolated figures grab our attention like actors holding center stage in theater or film. Every element of the painting converges to intensify the central event. The upholstery tacks, wallpaper stripes, and floorboards, all in sharp focus, point to and frame the stunning encounter. The dark split in the guitar handle between the tuning pegs echoes the naked genitals above.

The vividness of the setting that encases this extraordinary drama is one of the devices through which Balthus makes The Guitar Lesson really happen. Balthus the set designer has controlled it as carefully and knowingly as he has directed the action. It is the physical reality of the scene that makes the psychological issues rise to the surface so powerfully. Without the essential success of the painted canvas as a convincing illusion, and without its rich and alluring appearance, none of the other considerations would come into play as forcibly. However much the situation may be an invention, Balthus has captured the appearance of life. The surfaces shine or absorb luminosity as they would in actual life. The clear and raking light that falls on the wainscoting makes it palpable. The shadows read so tellingly that we feel they have been cast by actual objects.

The details have the effect of heightening our attention. The striped silk wallpaper with its contrast of lime and rust alerts us. And consider the floor. Balthus found the optimal means of evoking its wooden planks. They are precisely the golden yellow of highly varnished pine or oak. The artist has diligently put in every line of separation between the individual boards. He has used these lines to establish a one-point perspective system that is his own variation of Piero’s model. The floorboards veer at a sharper angle from the left of the canvas than from the right, so as to throw our vantage point distinctly off-center—close to the right-hand edge of the canvas, almost in line with the girl’s knees. Every device brings the viewer in.

The rendering of the texture of this wood justifies what Balthus has repeatedly said over the years about the futility of formal education for painters. Observation, direct experience, and experimentation—rather than anyone else’s instruction—had indeed been crucial to his success. Untaught, he developed an impeccable means of making wood both beautiful and real—with a thin speckling of brown on top of yellow. He achieved this by lightly flicking the dark color over the lighter, perhaps using a sponge to apply and remove the colors as necessary. The hue and intensity are flawless. The wooden floor practically has a ceramic glaze, like that of spatterware, but it is precisely what it is supposed to be. All the accoutrements are equally real. The pull of fabric across the teacher’s left breast—the one that is still clad—is authentically taut. We believe in her billowing puffed sleeves, the satin pleats and seams, the wrinkles at her left armpit. The young Balthus had already mastered the tricks of the trade to be as convincing as possible.

…

IN THE EXQUISITE LAIR in which The Guitar Lesson now hangs, the Modigliani opposite it and the two other Modiglianis and a Toulouse-Lautrec on view in the adjacent sitting room are all marvelous creations, but they also are all art objects—designed, enticing, quite different from life itself. The Guitar Lesson, on the other hand, is not a canvas; it is an event. Sitting there on the brocade bedspread as I looked at Balthus’s early masterpiece, I felt as if the two women were actually engaged in their act of passion before my eyes.

The previous time I had seen the canvas—fifteen years earlier, amid throngs of art students, elderly painters, and curiosity seekers at Pierre Matisse—I had had much the same feeling, and felt that everyone else did as well. We were viewing not just an artwork but a real occurrence: highly charged, perplexing, a mixture of exciting and embarrassing.

Initially we do not consider the artistic factors that made each element so plausible, any more than, when first seeing someone we know, we count the hair follicles or skin creases. Without identifying the devices whereby the feat is achieved, we feel that we are actively witnessing this bizarre, masculine woman attack a young girl who exhibits a range of responses. Flemish Renaissance masters like Jan van Eyck painted their Annunciations to make clear that the Immaculate Conception really took place. They articulated every windowpane and cast the Virgin and Gabriel in crystalline light so as to leave no doubt of the truth of the miraculous event. The young Balthus similarly found the means to make us believe the scenario of The Guitar Lesson.

For all his psychological elusiveness, he painted in order to impart precise information. The guitar and the girl’s and woman’s feet make shadows on the floor so that we know their exact angles. The teacher has braced both of her legs for optimal power. Her position is that of someone playing a cello or a double bass more than a guitar; indeed, she handles the girl like a large string instrument, squeezing the child’s inner thigh with the extended fingers of her left hand as she might press strings for a chord, stretching her right arm and folding the fingers of her right hand as if she were bowing, and then pulling the girl’s hair to the tautness of tightened bow strings. Metaphorically, she makes precisely the music she wants.

The expert instructress uses her hands like tools. She deftly squeezes her powerful fingers into the girl’s thigh near the child’s hairless mons veneris. Those fingers excite and dominate at the same time.

Meanwhile, the position and tension of the girl’s limbs make the child appear both active and passive. Her left leg dangles; she has succumbed. With the right, however, she supports herself. Balthus establishes both pressure and its absence in the placement of her feet and repeats the pattern with her arms. Every angle denotes either resignation or desire.

Similarly, he uses her hair to evoke her duality of feeling. Most of the girl’s thick locks cascade downward, loose in their fall, suggesting abandon. But then these are the strands being pulled forcibly by the teacher—their tightness echoed by the taut strings of the guitar on the floor. With her clenched fist, the instructress yanks the child’s hair with such violent energy that the pain is palpable. The teacher’s sharp tugging, and the indentations visible where she is pressing her fingers into the child’s inner thigh, gives the moment a screaming anguish that counters the languor invoked by the girl’s flowing tresses and collapsed right arm.

Yet for all this detail, it is again apparent that Balthus could not, or did not care to, paint human hands. The teacher’s left hand resembles a bird’s claw, with talons. The palm is too broad and puffy, the fingers too tapered and too alike, for a person’s. The wrist is proportionately too wide. This appendage belongs to a beast of the jungle. On one level, however, that discrepancy is appropriate. If as representation this arm and hand are all wrong, as invention they succeed. Like the woodenness of the baker in The Street, we accept them—and all of Balthus’s distortions—as part of the whole. Like a detail in a dream that will never jibe with our experience of real life, it coheres within the unique nexus of Balthus’s art.

THE WORD “AWAKENING” that Balthus cited as the underlying goal of his 1952–54 masterpiece The Room pertains equally to The Guitar Lesson. Its characters are relentlessly alert to the moment, and so are we when we look at it. A psychic intensity accompanies the physical high pitch. Desire, fear, and satisfaction are as vivid as the bones and musculature. In time Balthus would learn to conceal, to disguise, to dissemble. He would envelop his subjects, and his viewer, in a cloud. But here everyone is awake.

Every detail of the painting accentuates the greatest of all sources of awakening: sexuality. The violent lifting of the girl’s dress adds drama to the exposed nakedness of her genitals. The decorousness of the bows at her neck and in her hair and the presence of her schoolgirl’s white socks contrast the rawness of the scene in the way that seemingly innocent details add punch to pornography. The noticeable absence of her underpants (which Balthus always referred to, in our conversations, as the more English “knickers”) is another spicy detail. They are neither around her ankles nor on the floor; perhaps she was never wearing any. The dropped guitar takes on erotic portent: a curvaceous form that gets played across its dark, gaping hole. It is all so real that, just as we feel we might actually look around the corner in The Street and see another scene, we can readily picture the girl’s naked buttocks against the lining of her skirt.

Actions and feelings are at their pinnacle and frozen in place for the savoring. There is no subtlety. Lust has won; the teaching of music has come to a full stop. The teacher’s breast—a porcelain-textured, pure, milky white—zooms forward decisively. Her erect nipple catches the light sharply. The girl’s genitals are deep red, as are the teacher’s fingertips that press the child’s thigh; blood has rushed to these points. The girl’s labia pulse.

With her legs emphatically splayed, the teacher holds the girl in a wrestling lock. The older woman wears delicate black velvet shoes, but this ladylike touch merely emphasizes her powerful athleticism. Strong-boned, fully muscled, she commands her formidable strength ably, and uses it unabashedly. The teacher authoritatively cradles the girl’s backside on her upper thighs and across her crotch. Balthus has designed her body so that she does this with maximum efficiency. While the upper half is oversized, the lower half is miniaturized and diminutive; her arms are as long and thick as her legs. By enlarging the teacher’s head, reducing her scale waist-down, and stretching her legs, Balthus has made her titanic. The contrivance of her vast head enables her to dominate the scene.

As manipulator and painter, Balthus is remarkably like his stunning slit-eyed music teacher: imperious, disdainful of normalcy. He makes his creatures as he wants them; their plausibility matters far less than his personal aims. The painter has his protagonist’s daring, her power and control. And she has his seductive know-how. In their understanding of sexual response, the painter and the music teacher are one and the same.

If Mitsou depicts the pain of emotional separation and loss, The Guitar Lesson shows complete and absolute possession. The person who painted it, like the creature he has invented, will do whatever is necessary to achieve that steel grip.

WHEN I HAD MY PRIVATE VIEWING of The Guitar Lesson in Niarchos’s apartment, the girl’s flesh was so plausible that it made me feel guilty, as if I were pressing my fingers into her thighs. I could not for a minute buy Balthus’s idea that these sensations reflected my own lascivious desire rather than his intentions. The discomfiting sight of this half-comatose child submitting to tyranny felt like a nasty imposition, not a happy choice. The violation of a girl close in years to my own daughters was heinous. But the effects of Balthus’s virtuosity had left me no room for escape.

…

THE GIRL’S POSE CLEARLY derives from the Avignon Pietà at the Louvre. Among other things, The Guitar Lesson is a sexualizing of Jesus and Mary. The teacher cradles the child like Mary in a classic Lamentation format, while her single bared breast echoes the familiar nursing Madonna pose.

In the context of the times, however, this sort of heresy was not so unusual. Religious mockery was the height of vogue for the Surrealists. In the 1930 film L’Age d’or, Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel created sequences in which a pope has his naked big toe sucked and the Marquis de Sade’s protagonist from The 120 Days of Sodom appears in the guise of Jesus Christ. Max Ernst had recently painted a large image of the Virgin Mary enthusiastically spanking a bare-bottomed Jesus.

But Balthus’s strategy is entirely different from Ernst’s. Like the Marquis de Sade and other stylish technicians of sexual violence, he has set his fantasy in a nicely appointed domestic context. His unfailing worldliness and refined taste add luster to the savage behavior on view. The green and red wallpaper played against the yellow floor would, in someone else’s hands, be garish, but Balthus makes it fashionable. The elegant, impeccable trappings give the tale its spin.

The cosmopolitan Balthus has treated his lurid tale with both sangfroid and playfulness. Emotions might be squalid or tawdry, but not one’s clothing.

EVEN MORE THAN the satins and velvets, the piano makes the setting of The Guitar Lesson a real, bourgeois home.

For a painter of his ability, it was a fairly straightforward matter, this making of the piano. But Balthus chose to go about it in a way both childish and tricky. Relative to the people and the chair, the instrument is ridiculously small—a dwarf piano. The keys are as unrealistic as the proportions. They are zebra-striped—alternating black and white, of equal size and scale, directly next to one another—a far cry from real piano keys, in which the black sharps and flats are smaller and sit atop the larger white ones.

A piano requires neatness, repetition, and practice. It depends on training and refinement. In these ways it is both opposite and similar to the tempestuous scenario of the two women. The instrument suggests propriety, but it is also a provider of sensuous pleasure; properly harnessed, it can transport you into another realm. This well-conceived tool, expertly handled, is a vessel of intense passion. To achieve its power, it requires a level of expertise and discipline comparable to that which the teacher is now applying in another arena of sensuous pleasure. Know your devices; cultivate your skills; keep the elements in order; play your instrument properly. Then—Balthus seems to be saying—rapture awaits.

Yet the shorthand works. The piano seems quite real. Balthus knows how to communicate through deception; the sexual scenario is so riveting that few viewers would ever notice that he has had us on in the rendition of the piano.

Perhaps Balthus made those piano keys a sham for the same reason that he put the teacher in a sort of costume. The devices announce that the scene is an illusion. It’s make-believe, an act. We must take it with a grain of salt. This music lesson should be regarded as a fantasy, not as an event that actually occurred.

If The Guitar Lesson is theater, after all, then the cruelty of that vicious teacher and the submission of her victim do not have to be taken quite as seriously as they would if we treated the painting as realistic. Don’t fret, this is not really molestation and child abuse in which the paralyzed victim is having her share of pleasure. This is a painting about painting, a pose, nothing we have to worry about.

REVOLUTIONARY, The Guitar Lesson also established the extent of the artist’s links to the past. The prevalent artistic styles of the day would not have sufficed; he needed the traditional techniques whereby he could re-create surfaces and evoke details in a way that would enable him to convince. His deep, muted hues—reminiscent of Chardin and Géricault—position the painting within a known tradition. Balthus laid down a red ground at the onset that gives the paint its rich tonality; that timbre is especially remarkable in light of the prevalent palette of most artwork in 1934. Painters as diverse as the Surrealists, Matisse, and Kandinsky (then also in Paris) were all using brighter, sharper colors. Their work had a distilled, concentrated, up-to-date look. Balthus achieved his intensity in a very different way: one that deliberately depended on an expressive means mankind has known for centuries.

The look of artistic heritage is vital. Like the fiery people in the painting, whose faces and poses link them to a range of Renaissance prototypes, the colors, too, come from somewhere. As with Balthus himself, it is of the utmost importance that everyone and everything have a certain ancestry.

Yet, also as with the artist, that ancestry, while obviously very fine, is impossible to pinpoint. The colors in The Guitar Lesson stem from earlier art without having a precise equal in anyone else’s palette. Although similar in hue, they are lighter than Géricault’s, deeper than Piero’s. The scarlet of the girl’s jacket might exist in a Courbet hunting scene or an English portrait, but there it would be juxtaposed to the greens of the forest and the pale wash of a blue sky. Here it abuts yellows and other reds. Like Balthus, the palette of this painting derives from a range of prototypes but ends up being unique.

BALTHUS HAS CREATED the teacher in The Guitar Lesson with a rapid and knowing brush. The twenty-six-year-old painter appears to have dashed out her vicious slits of eyes and then, with a couple of quick strokes, to have shadowed them sinisterly. In a similar coup, Balthus has used a single, decisive, well-aimed line to tighten and clench the teacher’s steely jaw. These features may have required repeated attempts and hours of concentrated work, but they look as if they were done by someone who hadn’t a question in the world.

The teacher’s eyes allow only the merest squint; the student, too, sees little. Within her barely open eyes, her pupils are locked in place as if she is in a trance. We, the witnesses, have been made to see every lurid detail in clear light, but the participants cannot look.

Balthus is the one in control. Having determined to expose his viewers to an incident sure to excite them—either to titillate them or to make them supremely uncomfortable—he has also chosen to permit the participants to avert their vision.

TOTALLY IN CHARGE, tackling the most provocative subject he would ever attempt, Balthus did some of his best painting. The artist might occasionally hit his stride again, but here—frankly engaged by violence and the depiction of dominance—he was at a peak. Later in life, cloaked beneath layers of facade, Balthus would not be the same. The elegant nobleman of the 1970s and 1980s, embraced by his coterie and aware that any painting he produced was worth a fortune, would be considerably diminished in strength and skill. Visually and psychologically, his work would become too labored, its way of being disturbing too intentional. In his recent art, Balthus seems enigmatic and sexually provocative by design—as if his goal is to paint a Balthus. In The Guitar Lesson, he was unself-consciously himself.

One of his latest attempts to deflect viewers from this truth was a statement on The Guitar Lesson in a 1996 interview with David Bowie:

This one I painted because I was very hard up and I wanted to be known at once. And at that time you could be known by a scandal. The best way to get known was with scandal. In Paris.

Balthus would rather blithely declare himself a cad and a schemer than own up to one of his rare moments of unabashed candor.

“ALL ART IS AT ONCE SURFACE and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.”9 So Oscar Wilde writes in the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray.

“It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors,” declares Wilde. And so Balthus claimed to me time and again. If viewers find The Guitar Lesson—or the paintings he made of young girls twenty, thirty, and forty years later—shocking or titillating, repulsive or seductive, they reveal only their own psyches, not his.

How fervently Balthus presents himself as the passive, harmless observer and counsels us to accept his work as beautiful fictions, psychologically irrelevant. The credo is Wilde’s: savor the aesthetic enchantment and leave the rest alone.

THE COUNT DE ROLA—leaning back on the settee in his mix of silk and twill, blowing smoke rings into the palatial sitting room of his eighteenth-century chalet—made himself clear to me. Living as an actor, inhabiting a stage set, painting people as if in costume plays, he has chosen his own course: everyday existence as a fancy dress party.

The duo in The Guitar Lesson are also performers. They, too, act out their private fantasies. Like their creator, they cast a spell without ever really meeting our eye or engaging with us. They betray passion yet remain veiled and impenetrable.

The Guitar Lesson is loaded with signals without answers. The girl’s knees glow almost as red as stoplights. They look rouged; they are either scraped or blushing. Why is there so much color to them? Has she been kneeling for some previous sexual rite or punishment? Or is their hue simply a reminder of her age, that kids get scraped knees? Or would Balthus claim that the color simply went to the knees because she was placing her weight on them? Does Balthus have any idea why he made them this color? Was this just his caprice of the moment? Had he seen a little girl near the Rue de Fürstemberg with unusually red knees and used her as his imaginary model?

Yet it is hard to believe that someone as precise about his details, personal and artistic, did not have some purpose—concealed though it may be—in accentuating both the rosiness and the nakedness of those knees with the white socks folded down just beneath them. Even though Balthus today would have us forget this painting entirely, and would probably write off the color of the knees purely as a necessary touch of red on that part of the canvas, it is hard to buy his and Oscar Wilde’s pronouncement that it is only because of our own hang-ups that we see something more and are curious about its origins.

Or should we leave the artist in charge, just as the music teacher is?

After all, it is a delight to be this seducer’s prey. To allow oneself to be conquered, however confounding the submission, is shown in The Guitar Lesson to be a glorious pleasure. Even if the young initiate is holding on to that plunging neckline for dear life, her struggle is over and she is resigned. The viewer of the painting should be similarly entranced. To be forcibly overwhelmed—to be manipulated sensually and violently—is, in this painting, to be transported to a new peak of experience, a hitherto unimagined high point. How marvelous to succumb, whatever the proportions of pain and delight may be.

THE TEACHER IN The Guitar Lesson is Balthus himself. I do not mean this metaphorically; she is a self-portrait in drag. After an hour of sitting on the canopied bed in Niarchos’s lair and studying the painting, I realized this with a jolt.

I had been staring at the teacher’s face and trying to reckon with her personality. This powerful expert on sex held me rapt with her alluring appearance and her visible will to exact total control. Then I saw—without any question whatsoever, although I had not recognized the fact before—that it was Balthus’s own face. The features are identical to what we see in photos and self-portraits from the period when he painted this picture; the look of determination is exactly what I had come to know in Rossinière. The satin-clad music teacher with her milky white breast and thick long coif is not simply Balthus; she is Balthus less disguised than in many of his other roles.

She has Balthus’s pointed chin, sharp jaw, large narrow nose, strong cheekbones, and thin lips. Her eyes have the same cattish squint as his. Her skin has his pallor. This is the same face with which he showed himself in The King of Cats and Cathy Dressing. And the music teacher has Balthus’s personality—intense, mischievous, seductive, domineering, irresistible. She achieves to a tee the artist’s goal of being the one in charge, able to make the recipient of his charms submit with minimal resistance and enjoy the submission.

Like Balthus as a painter and a man, the teacher taunts as she seduces. Introducing her prey to the world of pleasure, she makes the receiving of her delights a complex, uncomfortable process. The enthusiast of Balthus’s paintings may not actually succumb like the child bent across the teacher’s lap, but the controlling, withholding Balthus commands his viewer’s reactions as surely as the teacher manipulates her victim’s awakening to sex. In The Guitar Lesson, the providing of thrills is perilously close to the administration of punishment; pain and happiness are kin. The same can be said of the act of observing Balthus’s art: it is an excursion into aesthetic glories forever halted by uncertainty and discomfort.

The protagonists in The Guitar Lesson are as alarmed and bothered by their situation as they are gratified. Having gotten where she is by her own devices, the teacher appears tortured. Perhaps shame and guilt accompany her sadism; she may be as masochistic and self-punishing as she is hedonistic and commanding. Whatever the cause, her face betrays conflict. Similarly, the girl, while slightly enthralled and rhapsodic, is also miserable.

The scenario links wish fulfillment with punishment. The teacher both introduces the girl to pleasure and takes her over her knee for it. Balthus’s much loathed Sigmund Freud provides some insight here in his discussion of punishment dreams: “They fulfill the wish of the sense of guilt which is the reaction to the repudiated impulse.”10

Balthus introduces such guilt throughout his work—in the explicit wickedness of sex in The Guitar Lesson, and in the more subtle nuances underlying the tone of his later work. Sex becomes naughty; pleasure and punishment and violence often exist in tandem. Physical pain is often seen as part of erotic pleasure. And the characters that seem so sexual are often equally demonic.

To study the child’s face, by the way, the viewer practically needs to look at the canvas upside down. Then, from the proper angle, we realize that the girl is the same character as the boy in The Street—which is to say Piero della Francesca’s Eve from Arezzo. She has the identical dimple below the full lips, the Romanesque arched eyebrows, the flat forehead, the nose plane. Time and again, Balthus paints the same people—in a fantastic range of guises. There are only a few archetypes, and the issues are recurrent.

A PEN-AND-INK DRAWING Balthus made in 1949 corroborates that the female teacher is really just Balthus at a clever remove. In this Study after “The Guitar Lesson,” the aggressor—now stripped to the waist—is male. His face has virtually the same features as that of the teacher in the 1934 painting. Only now, with short hair—and the slightly feline, demonic cast Balthus traditionally gives himself—the dominator is unquestionably the painter himself.

In this drawing, the Balthus character holds by his teeth a piece of material that supports, like a sling, the nude girl sprawled across his lap. Stretched taut around the small of the girl’s back, this harness is a unique, and highly clever, contrivance for domination. The man in charge is that much more of a brute for his ability to use his teeth to support the weight of the woman’s torso. With his head almost directly above the girl’s genitals, at which he stares avidly, he resembles a lion about to savage its prey.

Study after “The Guitar Lesson,” 1949, ink, 28.5 × 19.1 cm (photo credit 10.1)

The man who told me repeatedly that there is no eroticism in his art, who constantly denied (while perpetually bringing up) allusions to Humbert Humbert, who depicts himself as the beleaguered aesthete, has in both of these versions of The Guitar Lesson openly displayed the lust that consumes him. He routinely protests when others claim it, but he shows himself ravaged by passion. His obsession is with the female body just on the brink of womanhood: as seen both from her own point of view and by her seducer. And what was so overt in the early work would, in more subtle form, underlie all of his art through the years.

The autobiographical fantasy of The Guitar Lesson must have been a happy one for its maker. The teacher has won the battle with a victory that is as absolute as it is original. Mitsou may have gotten away, but now the love object has been captured. Balthus would keep her that way.

THERE WAS, INDEED, one young woman whom Balthus would have liked to have had in his lap when he was painting The Guitar Lesson. She was not prepubescent, and there is no saying whether he wanted to pull her hair, but he certainly craved more of a grip than he had. Antoinette de Watteville may have consented to sit for her portrait and accept Balthus as a friend of the family’s, but in 1934 she was not yet returning the degree of affection he felt for her.

“Blonde, beautiful, wide-eyed, voluptuous, serene in the self-assurance of her physical and social distinction,”11 Antoinette was everything the young artist adored. Balthus wrote his friends that she embodied the spirit of youthful femininity. Their age difference was insubstantial—she was twenty to the artist’s twenty-four when they met—yet, Balthus confided, he saw her as the ideal, quintessential young girl. He said she conjured an atmosphere of delicious hot chocolate: the perfect taste of sweet, unblemished youth.

Antoinette also had rank and fortune. The de Wattevilles were one of the most prominent ancestral families in Bern, their mansion grand and opulent. Balthus was enamored, but to no avail. Antoinette has said subsequently that, at the time, she did not want to be married to a poor painter.12 It has been reported that she smirked at Balthus condescendingly.13 Whatever the extent or the causes of her dismissal of him, Balthus was stung by the rejection.

As the artist who has entered a fine household and taken its resident maiden by storm, the Balthus doppelgänger in The Guitar Lesson is a stand-in for the person the painter wanted, but was not yet permitted, to become. A single woman was not all Balthus wished to conquer, and he did not necessarily intend to have her quite so brutally. But, exaggerated though it may be, the position of the music teacher is an apt equivalent for what Balthus desired. He wanted to take hold, to be the one in command.

Yet the student, too, partially represents Balthus: spellbound, seduced, held captive by a strong woman psychologically if not physically. Had Antoinette shown a sign of wanting to take him by force, he would probably have been delighted. Balthus put his face on the conqueror, but the schoolgirl was also a form of self-portrait. By his own admission a perpetual adolescent, he readily identified with the young initiate into the world of sensuous and aesthetic response. As with most sadomasochistic fantasies, the dreamer was both players at the same time.

WHENEVER BALTHUS BROUGHT Ian Fleming into the conversation, he would invariably raise his eyebrows and label him “amusing,” sometimes elevating him to “frightfully amusing” or “terribly amusing.”

James Bond’s inventor was among Balthus’s favorite acquaintances of the 1930s, both because of the writer’s creative intelligence and because of his upper-class English ways. But Fleming, particularly in that time period, had other sides to his character which make Balthus’s lifelong fondness of him—and the wry grin he made when recalling the writer—all the more curious. Fleming

may have been intelligent, charming and witty … but he was also a gold-plated phoney, a chancer, a ruthless, brutal womaniser, a sadist, a pompous snob, a toady, a chauvinist, a nihilist, an opportunist, an egocentric devoid of shame or guilt who cuckolded his best friends without a second thought, a miserable man with an emotional age of a 12-year-old.… He kept a collection of pornography, mostly about flagellation, and showed it to women he brought to his flat. Although most of it depicted men as the victims being beaten by women, Fleming reversed these roles in real life and mercilessly wielded the whip himself.… Luck favoured him when he met Ann Rothermere. As a girl she had written in her diary, “Why do I like cads and bounders?” In Fleming she found the cad of her life. He determined to “whip the devil” out of her. Her friends noticed that she was always black and blue when Fleming was around, and the letters between the couple are peppered with loving phrases such as “10 on each buttock”; “I want you to whip me and contradict me”; and “Be prepared to drink your cocktails standing for a few days after my return.”14

We will never know how well Balthus really knew Fleming. It is possible that he only saw the Englishman in passing and trumped up their connection to impress me. But to use the word “amusing” as the operative adjective for this sort of character is a fairly singular taste. The Guitar Lesson makes clear, however, that for Balthus—at least in his fantasy life—there were, quite literally, no holds barred.

IN THE SAME TIME PERIOD when Balthus was painting his scene of the androgynous music teacher and her young novitiate, Pierre Klossowski was devoting himself to a study of the Marquis de Sade. In 1933 Balthus’s brother published—in the Revue Française de Psychanalyse, a quarterly journal produced “under the high patronage of M. le Professeur S. Freud”—a psychoanalytic study of Sade. Each of the Klossowski boys addressed the issue in his own way, but they had emerged from the same childhood with a mutual interest in the sort of fantasies of power and dominance that got their name from the infamous marquis.

In the years since he had left Geneva, Pierre had flourished under the tutelage Rilke had arranged for him. Following his work with André Gide, he had established himself as a writer and translator. In 1930 he had collaborated with Pierre Jean Jouve, who had been a neighbor of the Klossowskis on the Rue Boissonade before the war, on a German-to-French translation of Les Poèmes de la folie by Hölderlin. That same year, Pierre had become secretary to the psychoanalyst René Laforgue. By the time the Princess Marie Bonaparte persuaded him to publish this psychoanalytic study three years later, he had acquired a considerable reputation for his extensive interest in the writings of both Freud and Sade.

In his essay on Sade, Pierre Klossowski explores Sade’s childhood development as a key to the understanding of his work. He acts in complete contradiction to Balthus’s counsel that it is heresy to consider the psychological sources of an artwork and to analyze the origins of its emotional content.

Pierre proposes that the Marquis de Sade had “a negative Oedipus complex.” The author of The 120 Days of Sodom was, according to the young writer, motivated primarily by an early hatred for his mother rather than the typical male hatred for the father. He characterizes the mother image in Sade’s work as a “tyrannical idol.” He points out that “it is the ideal of the devoted self-sacrificing woman that Sade is determined to destroy.”15 For that reason, “With fierce delight Sade undertakes the minute description of scenes in which the mother is humiliated before the very eyes of her children or by the children themselves.”16

Pierre Klossowski must certainly have been aware that his own brother was, in his paintings, depicting in elaborate detail related scenes of humiliation. Every major painting in Balthus’s 1934 show focused on creatures fitting Pierre’s description of the Sadean female. In The Window—the canvas in which a woman the age of a young mother has been pushed, terror-stricken, against the open sill—the painter himself is her apparent attacker. In The Street, the scene now amended depicts a female similarly in the throes of a humiliating experience. Both as tyrants and victims, the women in Alice and Cathy Dressing are precisely the types Pierre Klossowski identified as occurring in the Marquis de Sade’s work as a result of the marquis’s wish to subjugate his own powerhouse of a mother. Cathy lords her sexuality and uses it to torment her hapless admirer, Balthus himself. She is, in a sense, the victor in the scene, yet the artist has denigrated her totally by making her vain and ridiculous. Alice appears to have stripped herself and freely chosen her brazen pose, but she nonetheless looks sullen and miserable—like human meat at a slave auction.

The ultimate personification of what Klossowski calls Sade’s “idole tyrannique” is the teacher in The Guitar Lesson. Moreover, she is, generically and specifically, a mother image; by looking like Balthus, she closely resembles Baladine Klossowska. When Balthus was twelve and he was photographed on several occasions with his mother and Rilke, he and Baladine appear strikingly similar: with identical large noses, thin mouths, deep-set eyes, hollow cheeks, and nearly the same thick black pageboy-length hair. Whatever his deliberate intentions were, Balthus made the teacher an amalgam of himself and his mother.

The object of humiliation in this canvas—the girl on the teacher’s lap—is the prototype of the character Balthus would continue to subjugate, albeit far more subtly, for the rest of his painting life. She embodies the female who would be his lifelong obsession, whom he would present in an endless array of poses. These seductive girls in their formative years would tend to appear slightly anesthetized. Beyond displaying the usual absentmindedness of teenage girls, they seem to have been temporarily stunned. Overwhelmed by their own sensuousness, these alluring creatures are lost in their own worlds, inaccessible except to the rare soul mate. Balthus was preoccupied by enchanting, enchanted, women who were often on the brink of puberty physically, and, even if older, acted with the self-absorption that belongs to adolescence. The artist had to ennoble and devour such females.

Is this young lady—that initiate in The Guitar Lesson who in effect would be the subject of Balthus’s art forever after—yet another version of Baladine? Is she a portrait, deliberate or inadvertent, of the young mother who, when her sons were teenagers, wrote Rilke that she considered herself one of the children? The look of unconsciousness indeed describes Baladine—in the state of mind to which she was driven by her passion for the irresistible poet who was her lover during the period when Balthus and Pierre might have wished her to be more adult and attentive to their adolescent needs.

Or is the girl in The Guitar Lesson simply Antoinette, succumbing at last? Perhaps so. Or a version of the artist—initiated at a tender age into blazing sexual awareness? The essay Balthus’s brother wrote contemporaneous to the creation of the painting allows both for the confluence of all of these characters into a single image and for a connection between this extraordinary painting and its maker’s own early experience.

THE ENGAGEMENT BETWEEN A BIOGRAPHER and a living subject is one of the most fraught of all human relationships. To keep my freedom—once I realized I was writing about someone as unscrupulous as he is brilliant, almost as talented at lying as he is at painting—I pretty much stopped meeting with Balthus.

My biggest problem was the way I enjoyed him and revered him whenever we were face-to-face; his charms blinded me to his faults. If I had given in to his nearly irresistible promise of friendship, I would ultimately have violated that relationship even more extremely than is already the case.

But even once I ceased accepting the invitations to Rossinière, I still returned there often in my mind. Writing about identity in The Guitar Lesson, I pictured Balthus reading it in the library of Le Grand Chalet. The problem is poor Nicholas’s, Balthus would kindly allow with a look of compassion and understanding. The disappointed artist had hoped I wasn’t “one of those psychological types.” He thought I knew better. Perhaps my mother was an idole tyrannique; the issue was clearly personal.