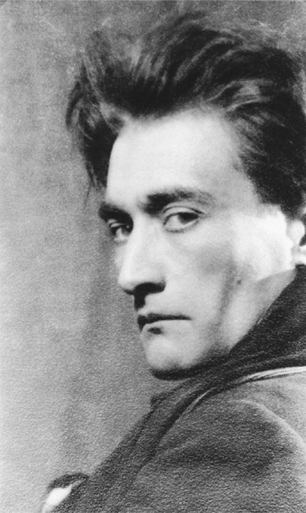

Lady Abdy, 1935, oil on canvas, 186 × 140 cm (photo credit 11.1)

The primitive, so-called sympathetic nervous system is a wondrous thing we share with all other species that owe their continued existence to being quick on the turn, fast and hard into battle, or fiery in flight. Evolution has culled us all into this efficiency. Nerve terminals buried deep in the tissue of the heart secrete their noradrenalin, and the heart lurches into accelerated pumping. More oxygen, more glucose, more energy, quicker thinking, stronger limbs. It’s a system so ancient, developed so far back along the branchings of our mammalian and premammalian past that its operations never penetrate into higher consciousness. There wouldn’t be time anyway, and it wouldn’t be efficient. We only get the effects. That shot to the heart appears to occur simultaneously with the perception of threat.…

—IAN MCEWAN, Enduring Love1

DURING ONE OF THE rare interludes when they were both staying at Muzot and enjoying a respite from the tumult of their separations, Rainer Maria Rilke and Baladine Klossowska made an outing to the Swiss city of Fribourg. In the course of that journey through the mountains, they decided to collaborate on a book in which his poems and her illustrations would appear side by side. Its theme was windows.

The slight, elegant volume was published by the Librairie de France in 1927, the year after the poet’s death. Called Les Fenêtres, it consists of fifteen poems dedicated to “Mouky et à Baladine.” Each poem is printed in distinctive hand-cut type, with lots of plain white space around it. Interspersed among the poems are ten of Madame Klossowska’s etchings.

The women created by Balthus’s mother are all locked in trances. The first, in profile, is framed by window mullions. Fixing her hair, she is completely detached from the act, as if absorbed in private thoughts. Another woman rests with her hands on a windowsill and looks off absently into the distance. She is in a spell, possessed by intense emotions of which we will never know the specifics. In one plate, a nude woman sprawls, seemingly overwhelmed, on a daybed. She is in a sensual paradise, with a vase of flowers at her side and birds visible through the skylight above. Elsewhere women lean and wave, and shutters open to unseen vistas.

The subjects are all transfixed; so, apparently, was the woman who created them. Baladine’s rather limp, awkwardly articulated etchings have an adolescent quality. These pleasant but flowery pictures appear to have been drawn in a semihypnotic state of bliss.

The manner and technique of Baladine’s window illustrations probably had little value for Balthus by the time he became truly serious about making his own art in the early 1930s. But his mother’s imagery and arrangements would nonetheless appear repeatedly in his work throughout his life. Time and again, he would pose women identically, surrounding them with many of the same details. His characters, too, would be in a state somewhere between reverie and agony.

WINDOWS—THE VEHICLES by which daylight enters rooms, the man-made framework that establishes the perimeters of what we see—would also be a leitmotif of Balthus’s painting. The artist must have known the meaning and symbolism his mother and Rilke ascribed to these forms. Windows suggest unknown territory. They open to distant information that, while present, is hazy. The walls around them create barriers that block entire areas from view. Balthus would often show adolescent girls languishing against a windowsill and gazing out through these openings to the outdoors that invoke the necessity of losing oneself to imagination.

Other central themes of Rilke’s poetry—the mirror and the rose especially—would repeatedly figure in the vocabulary of Balthus’s art. But the window, not just within the canvases but as the embodiment of the canvas itself, had particular portent.

RILKE WAS OBSESSED with windows. Walking around Bern and Fribourg in the early 1920s, he had decided that a serious history of them ought to be published. He felt that their shape determines our idea of the world. They help provide clarity, put us in charge, and diminish the risk of loss. They offset the incapacity and tenuousness he lamented in the preface to Mitsou.

as when we see her appear

framed by you; because, window,

you make her almost immortal.

All risks are canceled. Being

stands at love’s center,

with this narrow space around,

where we are master.2

By revealing a visual world that required no explanation and demanded nothing beyond itself, Rilke’s windows celebrated the act of seeing that Balthus would describe as the ideal of his art:

She was in a window mood that day:

to live seemed no more than to stare.

From a dizzy non-existence she could see

a world coming to complete her heart.3

Yet windows could also be treacherous. They have the capacity to bring on qualms and make us anxious at the edge of a precipice:

You propose I wait, strange window;

your beige curtain nearly billows.

O window, should I accept your offer or,

window, defend myself? Who would I wait for?4

It is, above all, that role that these openings in the walls assume in Balthus’s art.

ONE OF THE SEVEN PAINTINGS in Balthus’s show at the Galerie Pierre was The Window (color plate 6). He painted it in 1933, six years after the publication of his mother and Rilke’s volume. The canvas presents a desperate woman pushed against a window ledge. She raises her right arm in a frantic gesture of protest and self-defense. With her left hand, she braces herself against a fall. The woman bares a breast; it appears that someone has violently grabbed her blouse by its frilly neckline and pulled it down on one side. Everything else the woman is wearing is still in place. She faces her unseen attacker in abject terror.

Viewing The Window, we take the role of the assailant—unless we are one of those rare people for whom this painting stirs up nothing at all, or who can turn away from it with moral repugnance or a virtuous sense of shock. The act of seeing this canvas implicates us. As when we look at The Guitar Lesson, we feel ourselves to be something between naughty and evil.

The woman looks as if she is being threatened with a lethal weapon. We picture the painter, whose vantage point we share, wielding a knife. Whether this was a deliberate comment on the role of the brush or an inadvertent revelation, Balthus was showing the act of painting to be a means of terrorizing. He could subjugate his portrait subject and hold her captive through the devices of his studio: the same means that ultimately enabled him to conquer a large audience. Art is a power struggle, a process of personal metamorphosis, a means of taking command and astounding the bourgeoisie. Like the teacher in The Guitar Lesson, an artist must both thrill and intimidate.

The Window again makes blatant the artist’s need to prevail. He would later cloak and soften his approach, but he remained consistent in this compulsion to force alluring women to take the poses he commanded. Even inanimate objects must succumb to him. Tables would be locked in position, however awkward the angle; bed linens would be twisted this way and that. He would make beauty his prey.

WHEN THE ACTUAL MODEL for The Window, Elsa Henriquez, “first arrived at Balthus’s studio in the Rue de Fürstemberg, he opened the door dressed in his old army uniform, a dagger in his hand and a scowl on his face. He grabbed her blouse and tried to pull it open. Elsa recoiled in horror, just as Balthus intended.”5 The reticent young woman, educated at a convent, did not, however, actually bare her breast. Her exposure was a personal embellishment Balthus added to the painting to suit his own tastes after the fact.

The Window is another of Balthus’s personal fantasies. The horror-stricken woman is the captive of the celebrant of her beauty, like a butterfly specimen squashed between two pieces of glass. Having come into the room dressed as a seductress, she has ended up being the victim.

Elsa’s intense rhythm and springiness contrast markedly with the permanence of the setting. The rigorously constructed space—both of the very real room, which is graphically solid and fixed, and of the neighborhood, which summons a world of order—accentuates Elsa’s tumult and vulnerability. The brute who has yanked her blouse and pushed her against the window ledge has made her his squirming prisoner. The woman looks as if she is about to be flattened or impaled—as if the force looming over her is big enough to crush her. Like a tool of bondage, her wide yellow belt is as tight as possible around her cinched waist. Her tapered skirt is stretched as much as the fabric will permit. Her breast seems to have been squeezed out.

Balthus has set up a situation where we blame the victim. The lacy, plunging neckline and beguiling brooch inform us that the woman arrived on the scene intending to allure. Her most arresting device is that oversized scarlet hairband with its billowing ruffles. Luminous and airy, this hairband resembles a halo—as if this is a saint who is being raped. On the other hand, it is also a coy device of its wearer’s. This puffy tiara is the sort of thing one of Manet’s demoiselles might have worn. Like the flower in Olympia’s hair, it is a tool for enhancing appearance. Along with Elsa’s tight skirt with its flared hemline, it is one of the ingredients that have driven her attacker to frenzy. The implication is that anyone who decks herself out like this deserves what she gets. The underlying premise, as in so many of Balthus’s scenes, is that the woman wants to submit; she has set herself up to be violated. In keeping with a basic pornographic assumption, Balthus’s women aim to seduce. Then the manipulatrices suffer the consequences.

BALTHUS, IN FACT, ASCRIBES a certain guile to women of every age. We see it in his shopgirls dressed with a mission; we see it in his young teenagers. They all have devices and a purpose.

I was struck by a remark Balthus made to his seventeen-year-old daughter one Saturday evening when I was in Rossinière. Harumi was late coming into the dining room for dinner; the rest of us had already been seated for about fifteen minutes. Preparing for a party in Gstaad, she had taken the extra time to change her hairstyle for the third time that day, and had dressed for the event in skintight pants and a low-cut blouse.

“Harumi, est-ce que tu va séduire le chauffeur?” her father asked her with a wry smile.

Of course, it was in jest; the driver was the amiable Leonardo. There was not a chance Harumi would make moves on him. By suggesting seduction, Balthus was, I thought, mocking its possibility. Earlier that same day he had told me, with his most approving smile, that his Filipino servants were “beautiful people. They are like children.”

For some reason, I continued—for several years afterward—to hear that sardonic question over and over in my mind, as if it were a key to something. It became like certain phrases you repeat time and again when free-associating in the process of psychoanalysis; you know it is important, without being entirely certain why.

On reflection, what was remarkable was the pleasure Balthus took in asking the question—and his relish at the quick and lively smile with which his daughter responded to it. Harumi was far too sophisticated to be taken aback; she enjoyed this sort of banter with her father. Indeed, she may well have been on her way to seduce some socialite that night.

Balthus visibly delighted in the exchange of mischievous grins with the gorgeous Harumi and in the reference to the “chauffeur” who would be driving her to Gstaad. The luxury must have represented the fulfillment of dreams he had when he was fourteen. Clearly Balthus also got a charge from the very idea of seduction.

WHEN WE FACE THE ACTUAL painting of The Window, the young woman’s exposed skin is alluringly silken. The astounding verisimilitude of this and other surfaces instantly takes us in. But within moments, nothing else is quite right. As usual, Balthus, having first made himself credible, distorts freely. He has transformed his subject’s body to suit himself. Her large breasts start too far down—on the lower half of her chest—while their nipples are too high. Her hip is lower and longer than it could possibly be. Her head is stretched, her forehead too wide. Just below her knee, the woman’s left calf is two-thirds the width of her waist.

She emerges as both dominator and victim. Her overly solid limbs and spiraling hips give her the brute force of the teacher in The Guitar Lesson. She could break wood or crush rocks with those legs. Yet for all her mass and strength, she is helpless. Her feet are off the ground; her arms and legs are flying this way and that; her left hand alone is her sole means of support. She raises her pitiful right hand—half the size of the left—with its fingers bent so as to be useless. This pathetic gesture is all the defense she can summon in her state of panic. And she has a black eye.

What made Balthus come up with the scenario of The Window? At his most forthcoming with me, he allowed that although he did not know why, subject matter of this ilk “interested” him. More often, he shrugged his shoulders and declared the issue irrelevant to the real concerns of a painter. Yet, entering the territory Balthus perpetually scorned, knowing that the artist would disparage me for saying so, I believe it is likely that Elsa was a stand-in for Baladine Klossowska. The real Elsa was only fifteen when she posed for this painting, yet she resembles Baladine in her hair and her solid, sturdy body. Either intentionally or unconsciously, Balthus thus empowered himself to push his mother through the very sort of opening that was hers and Rilke’s last mutual obsession. The painting is a son’s revenge. Now he could bare the maternal bosom with which she had betrayed him. And he could hold her at knifepoint against the very sort of window ledge where, throughout his adolescence, she pined endlessly for the man with whom she had replaced his father. The setting was the same as in her and Rilke’s book: in front of one of those windows about which she waxed so lyrical with her lover.

If you accept this reading of the painting, then Balthus is the perfect exemplar of what his brother termed the “negative Oedipus complex.” He has taken the side of the absent, thwarted father and vanquished his mother—or her representative—on his father’s behalf. Now, with this painting, it is her son, the all-powerful painter, to whom Baladine must answer.

Rather than have us consider such an interpretation, Balthus has, of course, consistently resorted to the rubric that he painted his provocative themes of the 1930s simply because he knew what it took to captivate his audience. But the idea that “only the picture problems were of interest”—as he so often insisted to me—does not fly. The painted canvas was his means for dominating certain women—Antoinette de Watteville, Elsa Henriquez, his mother—and paralyzing them.

THAT VIOLENT CONQUEST ENABLED Balthus to summon his artistic skills at their most profound. Technically and aesthetically, The Window is superb. The view out Balthus’s window on the Rue de Fürstemberg excels both as a rich urban vista and as an intricately conceived, rhythmically dynamic artistic sequence. As in The Street, Balthus has carved out the rooftops and gables and construction details of Parisian architecture with trenchant accuracy. He cares about roof tiles almost as deeply as the Dutch masters did, and has rendered them painstakingly with a personal and ingenious shorthand. He found the paint colors that authentically evoke the earthy red-brown tones of clay and brick. The vents and smokestacks and dormers are crystalline in the cool light.

It isn’t only the view outside that the deft twenty-five-year-old painter caught and imbued with charm. The open window shutter and the drapery on the right are entirely convincing. The total conception of the painting is equally impressive for so young an artist. The Window is a bold composition on a large, noble scale. It has the elaborate construction that the committee of elder artists had first commended to Balthus when he was copying Poussin. Before using the picture space as a setting for human drama, the artist laid it out in advance and articulated its broad angles as well as the interstices. He made real the distinction between inside and out by establishing them in contrasting light zones, and then, with remarkable assuredness, splashed the bright outside light throughout the darker interior wherever it might naturally fall.

Yet significant as the setting is, it functions primarily as background to the people who occupy it. Like Roger van der Weyden as opposed to his predecessor Jan van Eyck, Balthus brought human life to the fore while integrating it in the visual world at large. Balthus captured the lurid details of Elsa even more forcibly than the quotidian aspects of the setting. He achieved this in part because he has the French eye for clothing; he knows its effects, and has related the different elements like a master couturier. The skirt material truly pulls across Elsa’s thighs. Her body within is twisted with sharp physical tension. Elsa’s shoes, with their gratuitous bows, augment her coquettish side. The green stripes of her blouse are coordinated with a similar color in her skirt. The lace fringe of her low-cut blouse—a style that Balthus called “pleasantly old-fashioned” in his limited comments to me about the painting (he confined himself mainly to pleasantries on how Elsa was dressed)—is another example of the degree to which she honed her own image before being yanked out of her area of control.

Elsa’s red cheeks—brighter in the actual painting than in reproductions of it—are startling. She may be highly, rather ridiculously rouged—or blushing with the extreme change of skin color more typical of a child. If the former, then the redness is the result of her attempt to make herself attractive; if the latter, then she has an oddly young side and is agonizingly flushed with discomfort. There is also the possibility that she has been slapped. Our inability to discern whether this redness stems from a deliberate plan of Elsa’s or if, on the contrary, it is inadvertent and reflects the shock of being caught off guard or the pain of having been struck, is akin to our uncertainty in The Guitar Lesson as to whether the girl is anguished or delighted. The signals are bold, yet we cannot read them. Like the red knees of the girl in The Guitar Lesson, Elsa’s luminous cheeks startle us while making us feel that some key information has been withheld. The painter has imposed this ambiguity on the viewer, and led us to lose our bearings in the same way that he has reduced Elsa to confusion. He does to his viewers what he does to his women: excite and stun.

THIS DISTURBING CANVAS that Balthus conceived in his historic corner of Paris during the heyday of Surrealism hangs today in a football-crazy university town surrounded by the sprawling landscape of rural Indiana. When I made my pilgrimage to see it, the journey seemed far more unlikely than my visits to see Balthus’s other early output. Also conceived in near-poverty, those other canvases nonetheless seemed more at home residing in the lavish residences of people like the Niarchoses and the Agnellis than they would in the American Midwest. On my way to Bloomington, I stopped at a roadside diner frequented mainly by truck drivers. Downing the breakfast special, I felt like Humbert Humbert going off to see Lolita in a trailer park; it seemed nearly impossible that a player in such a worldly and urbane drama would end up here.

But Bloomington has a fine small museum, in spite of I. M. Pei’s refusal to put daylight in the right place. When I got to The Window, I was instantly overwhelmed by its artistic effect, and was happy to see it near one of Picasso’s surreal women painted a year later. Balthus’s painting is wonderfully lively, its tormented subject an intensely beautiful woman. The ravishing Elsa, caught in her web, emanates force.

Yet in little time, I came to feel that my reaction was that of an aesthete. After half an hour of note-taking, I spoke with one of the female student guards responsible for The Window in its current home. The painting, which she regards as “confrontational,” angers her. Some of its other attendants told me they avoid looking at it because of the pain they experience from its “cold, alienated” tone.

The Window got to Indiana initially because the painter William Bailey, who taught there one summer, encouraged its purchase, which was subsequently backed by several of his fellow figurative painters then in the university’s art department, all of whom agreed that it was a masterpiece. To its admirers it remains a jewel. But for many of the visitors to Bloomington, the canvas ranges from being upsetting to deliberately demeaning.

So Balthus achieved his goal: the painting deals a shock. Unlike other avant-garde works, The Window remains as provocative as when it was painted.

IF THE BALTHUS I CAME TO KNOW, both in person and in his late work, greets visitors with a dagger—even proverbially—it could hardly be better concealed. Was the persona adopted in my presence, so gentle and courtly, a sham and a cover-up? Had he truly outgrown his violence of the 1930s, or was that sinister, bizarre side so visible in The Window merely an act developed to shield his gentler core? Or is the reverse true, and the sweetness and refinement of the 1990s a front for the inherent cruelty?

What becomes unquestionable in Bloomington is that at least once upon a time Balthus acted with unabashed zeal in trapping and flattening an alluring woman. He did not flinch from the intensity with which he portrayed her as a culprit and then punished her for it.

What is also clear in Bloomington are the precision and exactitude, as well as the rare understatement, with which Balthus elected to render his unusual personal narrative. Balthus constructed his canvas mainly in a reserved and limited palette of yellow-beige, terra-cotta, and dark greens. The difference between these choices and the dominant mode of the time is especially apparent in the painting’s current setting because of its proximity to Picasso’s 1934 Artist and the Model.

The subject matter of the Picasso is surprisingly similar to that of The Window. Picasso’s model, her string of beads in place but her breasts bared, has been pushed backward with violence. Yet here the artist has used a new and individuated language all his own. And he has fashioned his victim in strikingly modern colors. Those hues have the effect of making us feel we are looking at something other than at the real world conveyed by Balthus’s tones with their earthy underpinnings. And Picasso’s painterly vocabulary distances us further; his woman’s subjugation is not as upsetting to the viewer as is Balthus’s.

The Cubistic forms and expressive colors make the Picasso as much a statement about painting as a real image. What Balthus lays out blatantly is here obscured. Abstraction cloaks the psychological immediacy and permits the viewers to feel removed. Balthus’s technique, on the other hand, brings us face-to-face with real life. The confrontation is not just Elsa’s and Balthus’s; it is our own.

I have tried to imbue the characters in my tragedy with the same sort of fabulous amorality that belongs to lightning as it strikes, and to the boiling explosion of a tidal wave.

—ANTONIN ARTAUD6

If crime lacks the kind of delicacy one finds in virtue, is not the former always more sublime, does it not unfailingly have a character of grandeur and sublimity which surpasses, and will always make it preferable to, the monotonous and lackluster charms of virtue?

—MARQUIS DE SADE7

TWO YEARS LATER, Balthus painted another woman at a window—only now the creature in distress appears about to fling herself over the sill of her own volition.

This large, rich, dark canvas was a portrait of Lady Iya Abdy. The diaphanous creature with flowing blond hair is dressed stunningly in a long maroon gown, with billowing sleeves and a full, flowing skirt, by the French designer Madame Grès. With one bare foot elevated on the baseboard, the angel-like actress looks as if she has just alighted yet will soon fly off again.

Her contrived gesture betrays a self-conscious theatricality. The pose is contorted, even by Balthus’s standards. With her left hand, she pulls back a transparent, gauzy curtain. She leans awkwardly, her head pressed into her right forearm, her right hand holding a clump of her own wavy hair against the window casement. This is clearly painful. Lady Abdy is more demonic than terrorized, but like the woman in The Window, she looks as if she is being forcibly pushed by an invisible agent.

Balthus painted the portrait in 1935, the year following his exhibition at the Galerie Pierre. This was around the time he was designing the sets for Les Cenci, a play by Antonin Artaud in which Iya Abdy played the role of Beatrice, its principal character, who is raped by her father and subsequently plots his murder. Les Cenci was the first production of Artaud’s “Theater of Cruelty.” These new connections—with Artaud, with Artaud’s radical concept of theater, with the playwright’s circle—were changing the young painter’s life.

Iya Abdy was a fine-boned, beautiful, fair, and blond Russian woman who had, after a brief marriage, divorced Sir Robert Abdy, the fifth baronet so named, in 1928. She had been at loose ends until getting involved with the Theater of Cruelty, which she had helped to launch by joining Robert Denoël, Artaud’s publisher, in finding financial backing for Les Cenci. Although she had done little acting before, the new venture suited her perfectly by providing her with the opportunity to be onstage, which she had been yearning to do.

Balthus had been instrumental in much of this. He had introduced Lady Abdy to Artaud and told Artaud about the version of Les Cenci by Percy Bysshe Shelley on which Artaud had loosely based his play. With Antonin Artaud—sinister, ferociously imaginative, passionately devoted to Balthus—the young painter entered into a powerful, symbiotic relationship.

They first met late one afternoon in 1932 when both were taking a break from their work at a Left Bank café. Balthus later told people that this initial encounter occurred at Artaud’s instigation. Whether this was actually the case or was, in retrospect, wishful thinking on Balthus’s part, it makes for a nice story. Balthus, according to an account for which he furnished the “information,”

was sitting one day on the terrace of Les Deux Magots. Artaud happened to be there and scrutinized him carefully. He went over to the unknown young painter, introduced himself, and said he would be happy to make his acquaintance. In Artaud’s eyes, Balthus incarnated the image of his double. Moreover, their physiognomies were so alike that their friends would take one for the other.8

Lady Abdy, 1935, oil on canvas, 186 × 140 cm (photo credit 11.1)

When I met with Pierre Leyris in Meudon, he amplified on the significance of Artaud’s and Balthus’s resemblance. Leyris says that Balthus’s “force of character was such that he could turn himself into the person he wanted. Once he latched on to an image—the sort of creature he wanted to be—he could metamorphose into the same.” In the transformation in which I knew Balthus, he had convinced both himself and the world that he was an elegant European noble—the refined, Aryan, aristocratic Count de Rola—but in the mid-1930s, the persona he chose was altogether different. His model was the brilliant, deranged Antonin Artaud. He absorbed elements of Artaud’s appearance and personality as if they were in his own genes. As Pierre Leyris explains, this phase in which Balthus sought to become Artaud was the artist’s “very dangerous period.”

Antonin Artaud, 1934, crayon, 24.1 × 20.3 cm (photo credit 11.2)

Antonin Artaud, Self-portrait, c. 1915, charcoal, 15 × 10 cm

Yet the Artaud role came to Balthus naturally. He and Artaud initially had a lot in common not just in appearance but also in personality. Artaud was “an erudite, melancholy French aesthete, of extraordinary, if alarmingly morose, facial beauty.”9 The description would have applied equally to Balthus. Both Balthus and Artaud were gaunt and hollow-cheeked, with dark, deep-set eyes, similar large, angular noses, and shocks of black hair.

A drawing of Artaud that Balthus made during the rehearsals for Les Cenci is easily mistaken for a self-portrait. They were at the Café du Dôme, and Balthus drew it on a piece of Dôme stationery. One of his most frequently reproduced works, it appeared first in the May 1935 Bête Noire edited by Tériade and Maurice Raynal, and it has been in practically every major publication on Balthus. What makes it so remarkable is that not only does Artaud have Balthus’s face, but he has the artist’s primal force. The fiery, bone-lean visage belongs to someone who holds secret knowledge.

Born in 1896, Artaud, like Balthus, had been a prodigy. At the age of fourteen, he had started a magazine. He then went on to do theater work under the actor-director Georges Pitoëff—who was also esteemed by Rilke and to whose performances Rilke had taken the Klossowski boys when they were both teenagers in Geneva. Artaud had joined the Surrealists, but in 1926 had been excommunicated from the movement because his fellow members considered him to be concerned only with his own mind and private literary interests rather than with the world at large. Balthus would have identified with the rejection.

Artaud claimed to be uninterested in human relationships. Content to be solitary—a “maudit” or “infernal creator” in the tradition of Baudelaire and Rimbaud—he was Balthus’s sort of outsider. He compared himself to the sinister Usher, whom he played in The Fall of the House of Usher. Like Balthus, the actor-writer-director was brazen and completely original. The same year the Surrealists expelled him, the impassive, mournful Artaud was Massieu in Carl Dreyer’s haunting silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc; as the monk who tells Joan she will be burned at the stake, he could hardly have been more demonic, or more handsome.

Before founding the Theater of Cruelty, Artaud publicly attacked Western theater. He lamented its focus on psychological and social issues. Profoundly moved by an Oriental theatrical group that had visited Paris, he preferred their emphasis on gesture over words. Artaud declared that language was flawed compared with nonverbal communication and direct experience. Complaining that in most plays problems were stated and then settled, Artaud felt that art need not necessarily provide solutions.

Artaud was especially affected by a performance of Balinese dancing he saw in July 1931 in an exhibit of works from the Dutch colonial empire at the colonial exhibition in the Bois de Vincennes. Its appeal lay in its lack of words and its dependency on light, color, and movement. Artaud agreed with the concept of a religious or magical role that non-European societies accord to art, and prized primitive rites in which spectators are awed and terrified. Theater, in turn, should induce trances in its audience and disturb their mental tranquillity.

These tastes, which captivated Balthus when he met Artaud, coincided with the young artist’s own beliefs. Balthus often spoke to me of his admiration for the silences of Oriental culture, and for Chinese mythology with its symbolism. He disdains language much as Artaud did; he, too, eschews resolution and summary statement—in deference to ambiguity and open questions.

While Balthus has never explicitly embraced Artaud’s goal of putting his audience into a trance, he has implicitly adopted that approach as well. The glazed characters in Balthus’s paintings stare off into space in their own nonverbal worlds; viewers of these paintings become transfixed in the same way. Atmospheric haze prevails. Visual absorption supplants steadfast conclusions. This is precisely what Artaud advised: an attitude toward human behavior in which normal morality and rationality are insignificant.

FEW MAINSTREAM ART CRITICS in Paris had bothered with Balthus’s exhibition at the Galerie Pierre in 1934, and those who did dwelled mainly on the scabrous subject matter. Even the other painters and art viewers who were buzzing were not necessarily saying what Balthus wanted them to say. But in an article that appeared in La Nouvelle Revue Française shortly after the show closed, Antonin Artaud recognized the young artist for certain qualities Balthus himself believed in.

Artaud’s five short paragraphs thereafter became among the few texts on his work that Balthus has tolerated. It has been reprinted in the Tate and Centre Pompidou catalogs and quoted in other sanctioned publications. It acknowledges sex and violence more than the artist’s current taste allows, but it also zeroes in on the painterly method. Artaud’s commentary treats Balthus’s work as the embodiment of the writer’s own wish to fix certain images in all their power and to evoke a physical and psychological atmosphere through visual rather than verbal representation:

Balthus paints, primarily, light and form. By the light of a wall, a polished floor, a chair or an epidermis he invites us to enter into the mystery of a human body. That body has a sex, and that sex makes itself clear to us, with all the asperities that go with it. The nude I have in mind has about it something harsh, something tough, something unyielding and—there is no gainsaying the fact—something cruel. It is an invitation to love-making, but one that does not dissimulate the dangers involved.…

What we have here is the technique of J. L. David’s day in the service of an inspiration that is entirely of our own time; an inspiration full of violence that is just right for our diseased epoch. These are times in which the artist is perforce a conspirator. If he uses “reality,” it is the better to crucify it.10

RAINER MARIA RILKE had understood and explicated the drawings of the adolescent Balthus as no one else could; Antonin Artaud was the seer of the next decade. In an essay about Lady Abdy in which Artaud discussed Balthus’s portrait of her, the writer recognized, as Rilke had, both Balthus’s extraordinary artistic ability and his unique relationship to the world around him. Artaud elucidated the way in which the artist entered into, and became, his subjects. His connection with what he painted was the same as with some of his acquaintances; to discern Balthus from the “other” was often impossible.

Balthus has painted Iya Abdy the way a primitive might have painted an angel; with as sure a technical mastery, with an identical understanding of the spaces, lines, lights, and hollows which constitute space; and in Balthus’s portrait, Iya Abdy is alive; she cries out like a writhing sculptural figure in a tale by Achim von Arnim.

It is the face of Iya Abdy and it is her hands which the light devours, but another being, who is Balthus, seems to have inserted himself beneath this countenance and within this body, like a sorcerer who might take possession of a woman with his soul while he himself is stabbed in his bed.

And this same Balthus who makes Iya Abdy into a mysteriously incarnate ghost has made a stage set for my play The Cenci that might well be for ghosts, as awe-inspiring as a ruin in a dream or a gigantic ladder.

For he, too, is a creature of noble breeding. A kind of forgotten hero; and it is good that the incredible subject of The Cenci should be the occasion on a stage for the encounter of gigantic beings.11

Rilke had focused on the young artist’s espousal of elusiveness and of the haziness of visual and psychological truth. Artaud identified the quality of sorcerer, and dwelt on his eradication of traditional boundaries. Balthus needed either to become the people who obsessed him or to possess them.

WHEN BALTHUS MET HIM, Artaud had recently published Héliogabale, a study of an infamously cruel and tyrannical Roman emperor. The book was illustrated with six small designs by André Derain. In his post-Fauve years, Derain had become one of the most independent artists in France, courageously traditional. Rejecting modern trends in favor of an allegiance to the lessons of Courbet and to a dependence on nature as the beginning and end of his art, the gifted and witty Derain was a great favorite of Balthus’s. Derain’s illustrations for Artaud’s book were little more than thumbnail sketches, but Héliogabale represented a collaboration between two contemporary voices Balthus admired almost above all others.

The hallmark of the reign of the flamboyantly homosexual Heliogabalus was an imaginative cultivation of sexual perversions. The first section of Artaud’s book, “Cradle of Sperm,” opened:

If, around the corpse of Heliogabalus, dead and unburied and slaughtered by his own police in the latrines of his palace, there is an intense circulation of blood and excrement, there is around his cradle an intense circulation of sperm. Heliogabalus was born at a time when everyone slept with everyone else; and we will never know where nor by whom his mother was actually impregnated.

Artaud wrote Jean Poulan of his fondness for sexual hyperbole. “There are excesses and exaggeration of images, wild affirmations; an atmosphere of panic is established in which the rational loses ground while the spirit advances in arms.”12 The same description suits The Guitar Lesson, The Window, Lady Abdy—and The Street as it looked in 1934, prior to its subsequent revision. Artaud’s words pertain equally to Balthus’s 1952–54 Room—as well as to those other rare paintings in which the view to elegance has not completely obliterated the underlying hysteria.

Artaud wrote of his 1934 hero, “Heliogabalus, the homosexual king who wants to be a woman, is a priest of the masculine. He realizes within himself the identity of opposites.… Heliogabalus is man and woman.”13 Artaud developed a similarly androgynous character in Le Moine, where the temptress who leads the monk astray is a female dressed as a young boy. Talking with me, Balthus denied the notion of such ambiguity in his paintings, yet throughout his art there are characters with dual identities or indecipherable gender: the manly teacher in The Guitar Lesson, the little girl/male gnome in The Room, the masculine female in Large Composition with Raven. In the 1968–73 Card Players, the sex of the two children is so difficult to discern that while some viewers regard the painting as showing a boy and a girl, I believe it depicts two boys: Balthus and Pierre Klossowski as children. Often, Balthus’s children sport pageboy haircuts—as he did at age twelve—that could belong to either sex. Characters who appear at first to be unquestionably female so closely resemble the angels of Renaissance art that they thus become male.

In Le Moine, a monk meets an innocent young girl, kills her mother, then kills her, and finally discovers that they were his mother and sister. In Le Jet de sang, scorpions emerge from under the skirt of a nursemaid who nourishes small, shiny beasts in her vagina. In some of Artaud’s other writings, women are threatened with dismemberment, destruction by vampires, and strangulation. He believed that terror and cruelty govern our fundamental instincts. Balthus has been insisting for years that he has none of the taste for sexual violence and sadism about which Artaud was so unabashed, but Balthus’s art begs the question.

Artaud felt that the imagery of dreams was evidence of an inherent human violence, the true eroticism of our psyches. When dreams are “imprinted with terror and cruelty,”14 they have a liberating effect. The plots of Artaud’s writings derived from a blend of his fears and fantasies—all of which he connected with the intrinsic human condition. While Balthus consistently maintained to me as to his other interlocutors that his work neither presents nor explores the unconscious, his art offers sharp testimony that he and Artaud were in the same camp. Balthus’s unsettling canvases of the 1930s—when the artist allowed himself the most candor—provide liberation in the spirit of Artaud.

To recognize rather than dispute the psychological depth and adventurousness of his art is to come to grips with both its true nature and its greatest value, however much Balthus now declares otherwise. Balthus’s early paintings possess the expansive and, ideally, guiltless quality that Artaud identified and celebrated in our dream life. Regardless of their maker’s reluctance to say so, their revelation of the human psyche is their most profound asset.

Man Ray, Antonin Artaud, 1926 (photo credit 11.4)

As in the artistic production of those non-European cultures embraced by Artaud, primal forces dominate undisguised. Balthus’s work joins the seemingly barbaric side of the human mind with the decorous. By now denying the violence of his art—indeed, by succumbing, as the Count de Rola, to complete Europeanization—Balthus is effectively negating one of the great merits of his work. For his art is a celebration of anger and turmoil as much as of grace and tranquillity. Its achievement is in showing the degree to which opposite forces commingle. Uncontrollable cravings thrive in the most ordered, unruffled settings. In keeping with Artaud’s mandate, Balthus could reconcile these polar opposites of human existence. Fantasies of murder enter the drawing room.

CONSIDER, BY CONTRAST, MATISSE. When Matisse’s characters take tea in the garden or play at a checkerboard, all is innocent and lovely; there is no suggestion whatsoever of violence. This was, in fact, at a great remove from the truth. I once discussed these idyllic scenes of Matisse’s family life with his son Pierre, who gave me an account that Balthus had probably heard as well. Pierre told me that just before his father painted those happy domestic vignettes, he and his brother would be fistfighting or throwing each other into the prickers in the rose garden. They played checkers with such apparent innocence only because they were ordered to do so when posing for their father; the atmosphere was complete artifice.

Henri Matisse may have painted his young son’s piano lessons as pleasurable events, but by Pierre’s account, his study of the piano was an unmitigated torture. When Balthus shows children playing a game, on the other hand, they are indeed schemers and fighters. Throughout his art, the malevolence is patent. He clearly accentuated—rather than disguised, as Matisse had—the violence and repression inherent in life. Precisely as Antonin Artaud recognized, Balthus’s more candid renditions of childhood experience, startling and unsettling though they are, are closer to the painful realities of life’s earliest years, the frustrations and power issues. For all of Balthus’s insistence on his own “wonderful childhood,” in his art he went far beyond the illusion of simplicity.

ANTONIN ARTAUD WROTE:

Apart from a few very rare exceptions, the general tendency of the era has been to forget to wake up. I have attempted to give a jolt to this hypnotic sleep by direct, physical means. Which is why everything in my play turns, and why each character has his particular cry.

Attempting to alert others, Artaud once gave a performance at the Sorbonne in which he deliberately acted out his own death by plague. He presented himself with contorted face, dilated eyes, and cramped muscles. Everyone laughed, then hissed, and finally walked out in noisy protest, banging the door as they left. The dramaturge explained the event to Anaïs Nin. He had wanted the audience to experience the plague itself “so they will be terrified, and awaken. I want to awaken them. They do not realize they are dead.”15

Balthus shared with Artaud both that disdain for the misty-eyed world at large and the goal of firing people up. Most people were numb, they believed. Balthus joined his double in wishing to force confrontation on these sorry souls. Intentionally or not, Balthus painted Artaud’s two archetypes: the sleepwalkers, and the people who look as if they have awakened screaming from a nightmare. And like Artaud, he willingly resorted to violence to induce the cry.

BALTHUS’S WORK GRIPPED Artaud largely because it examined the thrill of violence as if through a magnifying glass. At the same time that he wears masks, and masks the personages in his art, Balthus is the great unmasker.

In his Galerie Pierre review, Artaud laments “our diseased epoch.” The explanation for that term is offered in his writing about the Theater of Cruelty in which he states, “If confusion is the sign of the times, I see at the root of this confusion a rupture between things and the words, ideas, and signs which represent them.”16 Artaud saw Balthus as having a rare ability to eradicate that rupture. As signs representing life, paintings should reveal life as it really is: replete with its inherent violence, power plays, and craving for seduction. For Artaud, Balthus’s art achieved the task at which almost all other contemporary paintings failed.

Artaud wrote that theater should “force the sensibility and the mind to undergo a kind of organic alteration which helps rid poetry of its customary gratuitousness.”17 Balthus made paintings with precisely that capability. And he also espoused Artaud’s skepticism about words, insisting that there is no use in trying to bridge the unmanageable gap between spoken or written language and visual images. Paintings must be accepted like cats: as being beautiful and alluring yet elusive and, ultimately, incomprehensible. They are what they are; to deal with them intellectually is to miss the real experience.

Artaud mistrusted the whole notion of “civilization.” He felt that “civilized” people had distanced themselves from the innate forces in life in favor of various artifices; he viewed intellectualization—and the imposition of logic, systems, and forms—as diversions and escapes. For Artaud, Balthus was one painter who did not accede to the corrupting influence of abstract thought, who remained close to the mythical and the pagan. So for the rest of his stormy, often mad life, Artaud would passionately turn to, and write about, Balthus.

If Antonin Artaud had lived to see his clone and soul mate become the Count de Rola, with the poses and veneer Balthus adopted for himself and his art once he assumed that position, the founder of the Theater of Cruelty probably would have recoiled. On the other hand, he might have heartily approved. Balthus, after all, had turned himself over completely to an exalted state of gesture and myth. And in their powerful symbiotic connection, the two sunken-cheeked, angular young men with their shocks of black hair were united above all in their ferocious zeal to stretch and intensify earthly existence.

THE STAGE, TRADITIONALLY, is a place where an individual assumes the part of someone else and commands an audience. Theater was Balthus’s natural domain.

As a child in Berlin during the First World War, Balthus had thrilled at the news that his father’s sets and costumes at the Lessing and Deutsches Künstler theaters had drawn applause the moment the curtain rose. When Balthus was fourteen, he had submitted his own set designs for a Chinese play at the Munich Staatstheater: the ones that made such an impression on Rilke even if they were not used. He fared better as a young adult. A few months after the 1934 Galerie Pierre exhibition, Balthus designed the sets and costumes for Jules Supervielle’s adaptation of As You Like It at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. These were well received, with Antonin Artaud among their admirers. Artaud singled out Balthus’s dark woodland scenes of bold trees with thick foliage in his review of Supervielle’s production that November in La Nouvelle Revue Française:

All of Balthus’s forests in this production are deep, mysterious, filled with a dark grandeur. Unlike other stage forests, they contain shadows, and a rhythm which speaks to the soul: behind the trees and the lights of nature, they evoke cries, words, sounds; they are all imaginary conceptions in which the spirit breathes.18

This was clearly the person to design the sets for Les Cenci.

CONTEMPORARY CRITICAL RESPONSE deemed Artaud and Balthus’s one actual collaboration a fiasco, but historically it was a remarkable production. In a 1933 essay in which Artaud cited his purpose in launching the “Theater of Cruelty,” he explained that this was to be his vehicle for expressing his horror of the contemporary Western world in general and of the bourgeois realism that dominated its theater. His theater company would awaken people to the cruelty inherent in life. Artaud’s initial intention was for it to stage Elizabethan melodramas, a tale by the Marquis de Sade, and the story of Bluebeard. Les Cenci, performed in 1935 with Balthus’s sets and costumes, ended up being the company’s sole, short-lived endeavor.

Artaud depended on two sources for the story of the Cenci family. Besides Shelley’s five-act verse tragedy, he had Stendhal’s Chroniques italiennes, which contains a factual account of the historical events based on trial records. The central character—the monstrous Italian Renaissance nobleman Cenci—is so obsessed by his longing for his daughter that he tortures and rapes her. Artaud himself played the role. At the beginning of the play, he states his raison d’être: “I have one aim left in life: to fashion more exquisitely refined crimes.”19 But in the course of the endless bloodbath of the play, the villain ends up the victim; eventually Cenci is killed by assassins his daughter hires.

In staging this macabre drama, Artaud’s goal was to show “the things … which human speech is incapable of expressing, and to find things that no one can say, however great may be his natural sincerity and the depths of his self-awareness.”20 Rather than through dialogue, this could be achieved with “a whole language of gestures and signs in which the anxieties of the age will blend together in a violent manifestation of feeling.”

The sets were vital to that objective. Artaud called for scene 1 to be “a deep, winding gallery.”21 Scene 2 was “a moonlit garden.”22 Next, when an orgy occurs, “the scene resembles that depicted in The Marriage of Cana by Veronese, but is far more savage in atmosphere.” Act 2 opens in “a room in the Cenci Palace, containing a great bed in the centre.”23 Its second scene occurs in “an indeterminate place. Waste land, corridor, stairway, gallery, or any other setting.”24 After that, there are no further specific instructions. But with Balthus, the playwright got precisely the results he wanted.

THE 1935 PERFORMANCE of Les Cenci took place at the Théâtre des Folies-Wagram, an enormous music hall reached via a long, narrow corridor. Today it is the Théâtre de l’Etoile. Jean-Louis Barrault—who would eventually become, both as an actor and as a director, one of the great names in French twentieth-century cinema—helped Artaud produce it. In rehearsal, Barrault played the part of Béatrice’s younger brother Bernardo, although he dropped out before the actual performance. By one account, the problem was that Barrault had other commitments that created a scheduling conflict; by another, he quit acting because he could not tolerate Lady Abdy. Roger Blin also assisted in the production and played the part of one of the two deaf-and-dumb murderers. Roger Désormière composed the music, for which he used modern instruments and broadcast, through loudspeakers, prerecorded sounds of machinery, cathedral bells, and thunder. For Balthus, a relatively fresh arrival on the Parisian art and theater scene, this was a high-ranking and exciting team in which to be included.

The twenty-seven-year-old artist was equal to the task. His set designs corresponded to the atmosphere the playwright had in mind. In the eyes of viewers as perspicacious as Pierre Jean Jouve and Artaud himself, Balthus’s schemes were symbolically apt, and effective in their simplicity and forcefulness.

The artist developed two main sets that were altered throughout the course of the play. The first was an imaginary palace in which, as in a dream, the architectural elements did not quite go together. In the Italian style, according to Jouve it resembled

an enormous palace-prison à la Piranesi, but where an inner discord, contained within the conflict of colors and certain fragmentations of the forms, produces the dissonant sonority we nowadays expect.

The background, intended as a setting for scenes of torture, consisted of scaffolding, suspended ropes, and mysterious ladders going from nowhere to nowhere. Like ruins, the foreground had a disjointed grandeur. It had the trappings of a royal abode—staircases, columns, arches, and porticoes—without the reality: good practice for someone who would eventually adopt a noble past without solid foundation.

In the second set, used for the final scene, Balthus incorporated a number of symbols that appear throughout Artaud’s work. There was a wall of blind windows, darkened or shuttered. Flames suggested major destruction. And there was a wheel, to which Béatrice Cenci was attached.

Some of those motifs would recur in Balthus’s work forever after. In a less jarring way, they would continue to have the impact Balthus discovered when making these strident set designs. Blind windows and raging flames would remain central to his artistic vocabulary. Regardless of the bourgeois fittings that surrounded them, they would impart some of the same discomfort they brought to the Cenci backdrop. And even though, in Balthus’s later art, there would be no wheels to which characters might be affixed for torture, there would be plenty of women held captive and immobilized by other, less flagrant means.

In his program notes, Antonin Artaud proclaimed that Balthus had a perfect grasp of his spirit and intentions. The playwright characterized the first setting as “a phantom decor, grandiose, like a ruin in a dream, a huge ill-proportioned ladder.”25 Artaud referred to the painter as “one of the strongest personalities of his generation who understands wonderfully well the symbolism of both form and color: green, the color of death, yellow, the color of a bad death, he used this symbolism in his choice of costumes.”26 Against the austere colors of the set, Balthus put Béatrice in a black dress to exhort the assassins to kill her father, while cladding some of the killers in red and green.

From left to right: Pierre Asso, Cécile Bressant, Julien Berthau, Iya Abdy, and Antonin Artaud in Les Cenci (photo credit 11.5)

Sketch for “Les Cenci,” 1935, China ink, 30.5 × 38.1 cm (photo credit 11.6)

In La Nouvelle Revue Française, Pierre Jean Jouve described Balthus’s designs in such a way that they seem to exist before us, and discussed their significance to this production. Jouve treated Les Cenci as a collaboration between Balthus and Artaud, a devastating and effective representation of “our inner life”:

There is a great deal to be written about the secret symbols at work here beneath the surface of visible reality—as may be similarly observed in Balthus’s paintings. Thus: the scaffolding like a gigantic ladder and the round columns silhouetted against the sky which raise the Cenci Palace to an alarming height but still bear their own signification; the red curtains hanging like “iron rags” or clots of dried blood; the broken arches suspended in space. The fabrics of the costumes afford a brilliant contrast to this grandiose background, though the “living” substances never triumph over the inert matter of the stone facades, the staircases, porticoes, wheels, and ropes.

Antonin Artaud’s direction continuously animates this space in the most creative fashion: here we are constantly “at work.” The complex lighting, the movements of individuals and groups, the sound effects and the music all convince the spectator that space and time together form an affective reality. Artaud’s will, united with Balthus’s, is everywhere: excruciations appear in the somber rhetoric of Artaud’s own performance and in the incandescent beauty and childlike, primitive action of Iya Abdy.27

“This theater is not made to please,” Jouve concluded. “Artaud constantly plays against the house and wins. The spectator is continually upset, and sometimes hurt, by the sharpest tension.”28 That shock to the audience, the nerve-racking battle between artist and viewer, is the essence of the work of both Balthus and Artaud.

Les Cenci OPENED ON MAY 6, 1935, with an evening gala sponsored by such prestigious society figures as H.R.H. Prince George of Greece and the Princess de Polignac. Even though the opening and the production included numerous luminaries, and intellectuals like Jouve commended its pioneering force, most of the critics in Paris gave it terrible reviews. Radical though the philosophy behind it was, the play came off as an old-fashioned melodrama. And Artaud’s performance as Cenci was considered too extreme.

After seventeen performances, Les Cenci closed. The Theater of Cruelty was finished. In January 1936 Artaud, utterly depressed, left for Mexico—in quest of a place not destroyed by Western culture.

Man is made to live in the convulsions of anxiety, or the lethargy of ennui.

—VOLTAIRE, AS QUOTED IN ANDRÉ MAUROIS’S Byron29

IN MEXICO, Antonin Artaud came to feel that he had always been on the right track in believing “that madness, utopia, the unreal, and the absurd will constitute reality.”30 In the northern mountains, he participated in the rites of the Tarahumaras and joined them in taking peyote for days on end. He became obsessed with tarot cards and other aspects of the occult; the irrational world of the spirit became his reality. He also converted to Catholicism.

Yet having given up and denounced his Paris life, Artaud still maintained his relationship with Balthus. From Mexico, he stayed in frequent touch with both the painter and Jean-Louis Barrault. As Artaud became increasingly crazed over the years, Balthus and his work would be both part of the madness and an anchor within it.

MOST OFTEN, WHAT THE dramaturge had on his mind when he wrote to Balthus and Barrault from Mexico were his desperate financial straits. Fortunately, as he explained to his friends, he was able to make some money by writing newspaper articles. One of those essays, which appeared on June 17, 1936, in the Mexican paper El Nacional, was entitled “La pintura francesa joven y la tradición.” Concentrating on the current situation in French painting under the domination of Surrealism, and on Artaud’s belief system about painting since the Renaissance, its linchpin figure was Balthus.

Initially published in Spanish and soon translated into French (although it has never been translated into English), “La pintura francesa joven y la tradición” has remained an essential document in the limited canon of literature about Balthus. Of the writers on Balthus, Artaud was the one who talked with him the most—even more than Rilke. He saw the painter virtually every day of 1934 and 1935, and his account is both personal and astute.

Artaud’s essay identifies Balthus as a pioneer and radical at that moment in the history of painting. This text also depicts the forces that for Balthus were so tumultuous, perhaps of such unbearable intensity that the artist’s only way of handling them and emerging with his sanity intact subsequent to that period was to take the opposite course from Artaud himself. Artaud embraced his furies until they devoured him, whereas Balthus retreated under multiple protective shells. Reading this 1936 essay, we come to understand the origins of the layers in which the Count de Rola is now so securely encased.

Artaud opened “La pintura francesa joven y la tradición”31 by citing the young painter Balthus as the leading force in the current reaction against Surrealism. His essay contrasts the differing ways in which Balthus and the Surrealists approached reality. Artaud emphasizes the role of unconscious thought as the primary source of Surrealism, calling Surrealist painting a negation of the real in whose conception there was no difference between the world of dreams and that of reason. He viewed Balthus’s vision, on the contrary, as inexorably linked to reality.

It is an explanation that makes perfect sense when one considers how Balthus talked about The Street and The Passage not as images of sleepwalkers or contrived scenarios but, rather, as forms of everyday reality: familiar street corners with the neighborhood habitués hanging around. Balthus’s world, unlike that of the Surrealists, is not an imaginary one. It presents—if in a highly personal, offbeat way—Balthus’s reality. His paintings may not show your everyday universe, but they represent his. His women are not the bizarre creatures of the Belgian Surrealist Paul Delvaux’s beauty contests; they are—even if blatantly sexualized, even if they look abused—real women. His takeoff point was daily life as you and I know it; he would never have been remotely interested in Magritte’s sort of imagery of a sky seen through an eye or the simultaneous occurrence of nocturnal darkness and daylight.

The forms of Surrealist culture exist in hallucinatory light. Struggling against such divorce and destruction, Balthus confronts the world starting from appearances; he accepts sense-data, he accepts the data of reason as well; he accepts these things, but reforms them; I should prefer to say that he recasts them. In a word, Balthus starts from the known; in his painting there are universally recognizable elements and aspects; but the recognizable in its turn has a meaning which not everyone can reach or, indeed, recognize.

Artaud recognized Balthus as a total revolutionary—both against Surrealism and against academicism of every form.

To situate his friend’s work in the context of world art, the playwright declared that a certain artistic tradition was lost at the time of the Renaissance and had never previously been regained. “Painting has fallen under the anecdotal domination of nature and of psychology. It has ceased being a means of revelation and become an art of simple descriptive representation. It has lost that raison d’être, at once secret and universal, which made it, in the true sense of the word, magical. The culprits who betrayed that power were Titian, Michelangelo, and Giorgione.”

On the contrary, pre-Renaissance—so-called primitive—painting had this force that then evaporated. “The faces in primitive painting transmit the soul’s vibration, the profound efforts of the Universe.” Artaud credits Cimabue, Giotto, Piero della Francesca, and Mantegna with evoking “actuality,” with being near to the mysterious essence of being. “It is to this magical and esoteric tradition that a painter like Balthus belongs.”

Artaud considered Balthus, his mirror image, to be the twentieth-century heir to early Renaissance painting—with the “sacred and hieratic primitivism” of those earlier painters. Because of this, Artaud responds to Balthus as if to a hallucinatory drug. He cannot get over what he sees. What others might find bizarre—what makes others uncomfortable—was to Artaud, the author of Héliogabale, the creator of the Theater of Cruelty, an expression of truth.

Linking his doppelgänger to artists of the era of Cimabue, Artaud writes:

There is, in their representations, a kind of esotericism, a sort of enchantment, and by its lines the human figure becomes the fixed sign and transparent filter of a certain magic. This is Balthus’s procedure, which will reject the anarchic abandon and the more or less inspired disorder of so-called modern painting, and give us landscapes, portraits, groups which have their own code and of which the symbolism is not immediately apparent. Balthus has painted mysterious groups, a street down which parade the automatons of our dreams; he has achieved concentrated portraits in which, as though on an astrological chart of the heavens, a color, a flower, a metal, fire, earth, wood, or water permits the person represented to regain a true identity.

Artaud, as a poet, felt he was forever dealing with ungraspable ephemera. Artists like Balthus and Uccello, however, had the enviable control whereby they might dominate their own thoughts and impulses by capturing them on canvas.

Like Rilke and Jouve—and, later on, Camus and Paz—Artaud is yet another major literary figure to be profoundly moved by the individualism and unique forcefulness of Balthus’s art. Artaud wrote in “Pintura”:

Similarly, in a Balthus portrait, the figure evokes the element it most resembles in its life, character and spirit.…

He manages to impart life to objects in a light he has made his own. One might say that there is a Balthus color, a Balthus light, a Balthus luminosity. And the characteristic of this luminosity is above all to be invisible. Objects, bodies, faces are phosphorescent without our being able to say where the light comes from. In this realm Balthus is infinitely more skillful than Goya, Rembrandt, or Zurbarán, than all the great agonists of that painting which rises out of the darkness glaze by glaze to the light.

Allied to the science of color, Balthus possesses a science of space. He immediately knows just where to place on a canvas the touch that vibrates, following in this the great tradition of painting according to which the painted canvas is a geometric space to be filled. But within this painted, vibrating space, within this invisible illumined space, it is Balthus’s personality which summons the colors and shapes and upon them imposes his somber seal. He curdles them, as we say that an acid ferment curdles milk.

It is not Balthus who works with ochers, tawny reds, earth greens, bitumen, and lacquer blacks, but it is a fact that the world he sees sustains itself within this minor range.

Balthus’s bitter chromatics signifies chiefly that the life of our time is bitter. In his agile yet concentrated forms, Balthus proclaims the bitterness and the despair of being alive.…

With his angular and constricted drawing, his earthquake chromatics, Balthus, who has always painted hydrocephalic creatures with fleshless legs and long feet—which proves that he himself has difficulty supporting his own head—Balthus, when he has ultimately assimilated all his sciences of painting, will assert himself as the Uccello or the Piero of our time or even more as a Greco who somehow wandered into it.

INn 1937 ANTONIN ARTAUD returned to France from Mexico. He was soon certified mad, and was locked up in mental hospitals for the next nine years. This was a time of incarceration more than medical care. When Artaud got out in 1946, he was ravaged by shock treatments that left him toothless and emaciated. His cheeks even more sunken than before, he appeared defeated by life; he died two years later, seriously crazy and addicted to drugs.

Throughout his decline, the dramaturge remained loyal to Balthus. While he was hospitalized, Artaud kept chaotic journals in which the artist’s name periodically emerged. In the moments of respite when he was semicoherent and well enough to write more than haphazard notes, he often made Balthus the subject of his ramblings.

While some of Artaud’s writing from his later years was reprinted in the 1983 catalogue for Balthus’s exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, there is one essay by Artaud that has most certainly not been included in those publications sanctioned by the artist. Written in 1947, this is Artaud’s reminiscence about Balthus in his first studio on the Rue de Fürstemberg—and the suicide attempt the artist made, or appeared to make, a few months after the Galerie Pierre show.

In 1934 the two were such close friends that they saw each other virtually every day. It was Artaud’s habit to drop in daily between 6:30 and 7 p.m.

He lived in a studio in the Rue de Fürstemberg, a sort of shed on the roof, made of scaffolding, as if framed for eternity, where it seemed he would never stop climbing up and down, or rather remaining at the top of this scaffolding where something eternal or sempiternal was hammered together.

for in the Rue de Fürstemberg there is a brothel and there is also a chapel where some kind of filthy free-masons come to pray out of a huge emblazoned breviary apparently there are descendants there and relatives of some sort of a sect of old Rosicrucians, old initiates dressed and undressed, but who are dressed and undressed only upon entering and leaving the old house in the Rue de Fürstemberg, for with regard to the remainder of the interior they are purely and properly,

which is to say very

co

cho

WOE TO ANYONE seeing herein a shadow of pornography, woe and curses.

For there was on one side the life of balthus who had to live, to pay for the roof over his head, his sleep, his three meals a day, his work-site, that is, the place where he could work, and then the work itself, its value, its effectiveness.

It is well known what the undertow is:

that elastic motion the sea imparts to its own loins.

well, this article is like such a motion which I impart to myself in order to regard myself

in the depths of my own past.

and to regard myself regarding

Balthus

BALTHUS

The same Balthus

Balthus

Balthus dreaming in the depths of his own past.

The same Balthus all alone and who tried to commit suicide one evening, and whom I found all alone in his bed and to his left on a chair a little vial of 15 grams of Sydenham laudanum, and beside the vial a photograph. I looked at the vial, the photograph, and Balthus was hardly breathing at all, and it seemed to me that the allusion was too strong, too crudely strong for me to be able to accept it.

Suicide by laudanum was too much too banal, and suicide on account of a woman, suicide because of a lover’s despair for me to be able to accept it and admit it.

I had gone into the room to see Balthus the way I came to see him every evening around 6:30 or 7. The door was never closed in the evenings. Balthus was lying on his bed as he used to do sometimes, but somehow sunk into his own sleep, more than sunk: one can say

buried

actually

BURIED.

He was no longer breathing, he was dead, not dead like someone already buried in his coffin, but dead like someone.

And that was how I saw that terrible black corpse, black and poisoned, whom I confuse with a young man lying on his bed, dead and intoxicated on a certain bed in the Rue de Fürstemberg, in a house next door to a brothel, and who in the depth of the first judgment was fulminating and one after the other released, what he ought never to have done and which was the first sin, to paint in the anchored astral spirit all the paintings lining the wall and which seemed to be finished, when it takes a hundred million eternities and applications each one added to the next in order to produce what Balthus in fact better than Poussin, Corot or Courbet has produced: a callused hand of life, of an illuminated exterior which is not filmed but painted.

Artaud was something of an expert on laudanum. Anaïs Nin, his occasional lover, describes him with “his mouth with the edges darkened by laudanum, a mouth I did not want to kiss.”32 Artaud understood the use of this morphine-based medicament sufficiently to recognize that Balthus had been careful not to take too much.

Artaud was also guided by his intimate knowledge of Balthus’s nature. He deduced that this overdose was a staged act that Balthus was sure to survive. Moreover—as Artaud realized when he walked into the studio that fateful afternoon—the painter had timed his maneuver meticulously. Balthus knew that his friend would be arriving, as he always did like clockwork, at what would be precisely the right moment to rescue him.

When he found Balthus lying there, Antonin Artaud instantly called Pierre Leyris to the scene. Leyris described this to me when I met with him in 1992. When he arrived in the artist’s studio flat on the Rue de Fürstemberg, he, too, immediately recognized the overdose as a dramatic gesture more than a genuine attempt to take his own life.

Balthus had arranged his body and the photograph at his side as skillfully as if he had painted the scene. The comatose state was both real and a pose. Lying on that bed in his studio, Balthus resembled the major prototype of his art: limp, dazed, overwhelmed by circumstance. As always, Balthus was playing with perceptions, manipulating the psychological and visual elements to garner the desired response, focusing on how others would see him more than on his inner self.

But even if the scenario was a contrivance and Balthus meant to be discovered, he was still in a serious condition and required medical help. Together Artaud and Leyris rushed their friend to the doctor. Balthus was treated and in little time returned to his life as usual, but it had been a close call.

Describing this incident, Pierre Leyris provided a fascinating aside. The doctor was Jewish—and someone whom Balthus liked and respected very much. Leyris mentioned this to me as a specific example of the duplicity of Balthus’s perpetual anti-Semitic quips. In the 1930s there was no possible way for the artist to cover up his Jewish half—Baladine and Pierre Klossowski were still too much in the picture—and Balthus had close Jewish associates. This is one of the reasons Balthus’s presentation of himself later in life struck Pierre Leyris as so particularly pathetic.

…

AS PIERRE LEYRIS POINTED OUT to me, even in his “dangerous, mimetic phase” Balthus never lost sharp consciousness of his devices. If Balthus wished to become—and simultaneously endear himself to—Antonin Artaud, what better way to do so than to take his look-alike’s favorite intoxicant, touch the level of danger and extremis Artaud cherished, and finally be rescued by Artaud himself?