Working Girl (1988)

With Working Girl, Mike Nichols went Old Hollywood to tell a new fable of working-class female empowerment. With its social critique sweetened by old-fashioned star power in the service of romantic comedy, it’s the kind of film Billy Wilder might have made had he permitted himself pure fantasy. Released at the end of the year, in time for the nominating season, the film pleased audiences and received six Oscar nods, including Nichols’ fourth nomination as Best Director and no less than three actress nominations, Melanie Griffith for her lead role and Sigourney Weaver and Joan Cusack in support. Carly Simon was also nominated—and subsequently was the film’s only winner—for Best Original Song. Replete with the comparative iconographies of Manhattan’s capitalist towers and the modest blue-collar neighborhoods of Staten Island, another co-star of the film is the Staten Island Ferry, churning the liminal waters between ethnic, low-income America and the capital of capitalism. A familiar trope of Studio System romantic comedy is the mistaken, feigned, or assumed identity, which lends itself to a trademark Nichols thematic preoccupation: the pressure to assume and perform socially constructed roles. Reified performance has been at the heart of Nichols’ dramas and comedies since his earliest features—the “games” George and Martha play in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the “shows” Benjamin’s parents mount under the guise of their loving celebration of their son in The Graduate, Catch-22’s Colonels Cathcart and Korn asserting their deal with Yossarian to “like” them and say good things about them at home, and so on. “Performance” is at the very center of the drama in Nichols’ ambitious follow-up to Working Girl, 1990’s underrated cine à clef Postcards from the Edge. Working Girl’s mingled echoes of “Cinderella” and the Horatio Alger mythology of capitalist self-invention, two of America’s most persistently beguiling fantasies of rags-to-riches reward for the nobility of grit and dedication of spirit, imagine a woman afforded the opportunity to pretend her way into the Fortune 500.

As Tess McGill, Melanie Griffith is a contemporary Cinderella, with her little girl’s voice and grown-up curves, shown over and over by Michael Ballhaus’ camera. Sigourney Weaver, as Tess’ new boss, Katharine Parker, is also, like Tess, reduced to reclining cheesecake by the camera’s gaze when her skiing accident enforces her feminized passivity1; Harrison Ford as Jack Trainer, object of both women’s desire, gets significant shirt-off time, as do Alec Baldwin as Tess’ Staten Island boyfriend Mick and Elizabeth Whitcraft as Doreen, the woman angling to steal Mick away. In the context of Tess’ Cinderella story, no shot in the film seems quite so erotically provocative in its fairy-tale allusion as the shot of Tess, madly vacuuming Katharine’s house in high heels and precious little else to eliminate any trace of her past weeks of living literally in Katharine’s shoes (as well as her apartment, office, and identity). Working Girl is a Cinderella-story for adults.

The problems with audience reception of The Graduate—the Baby-Boomer embrace of Benjamin Braddock as counter-cultural hero despite scant evidence in the cinematic text itself—are if anything even more pronounced in Working Girl, which has the tidy concluding episodes of recuperative social comedy. Tess is rewarded with authorship of the deal she’d imagined and brokered under false pretenses; Katharine is punished for her malfeasance in trying—twice—to steal Tess’ idea. Jack and Tess are presumably left to happily-ever-after, as are the Staten Island couples whose dreams are more modest: Cyn (Cusack) and Tim (Jeffrey Nordling), and Mick (Baldwin) and Doreen (Whitcraft). The film is either Nichols’ most conventional or else one of his most subtly subversive, provoking polarized responses. Leonard Quart and Albert Auster label it “anti-feminist” in its “put down of the type of cold, manipulative superwoman” represented by blueblood striver Katharine (Sigourney Weaver’s character),2 while Deron Overpeck writes that, “at first blush, Working Girl appears to be an uplifting story of a woman succeeding in the corporate world.”3 Audiences could be forgiven for misreading its iconography of upwardly mobile feminist fantasy, but the final shot, a helicopter pull-back from Tess until she is lost in the glass and steel canyons of lower Manhattan, suggests the irony beneath the fantasy. In the larger context of Nichols’ career spent in dramatizing reified class, gender, and ethnicity, Working Girl is a reified daydream of the “contradictory expectations of women during the 1980s”4 spun from the cotton candy of “Morning in America” Reaganism.

* * *

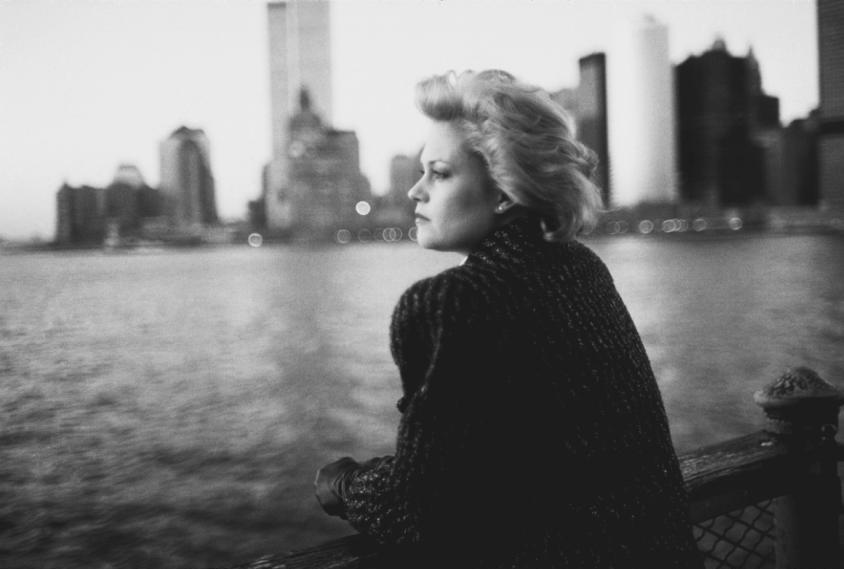

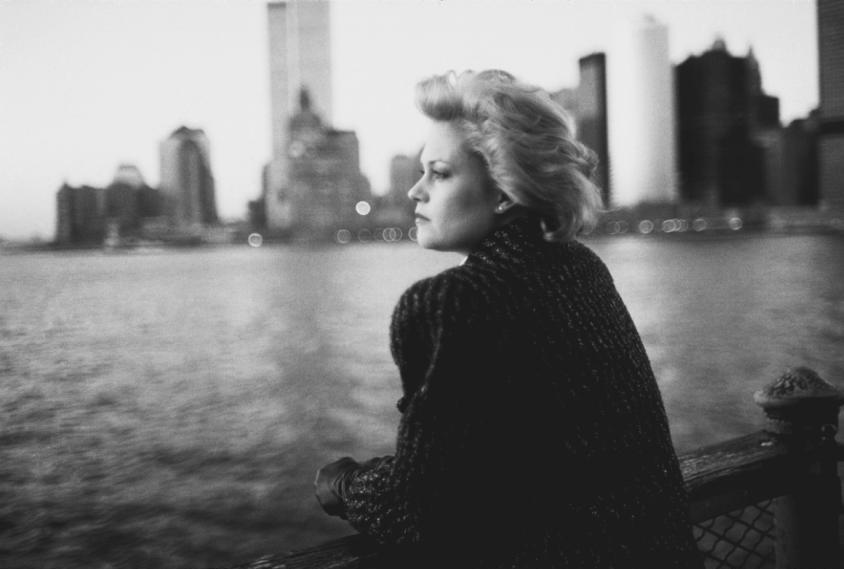

As the title naughtily suggests, Working Girl is a meditation on the sexualized commodification of the human person. Certainly the film’s opening moments set up the tension between the rhetorical egalitarianism of Lady Liberty in New York’s harbor and the reality of gender and class politics everywhere else, specifically within corporate culture. “‘I like doing stories about women,’” Nichols says, “‘because they’re the underclass in America.’”5 Carly Simon’s “Let the River Run” establishes a triumphalist context in its call for the “dreamers” to “wake the nation” to the shining ideal invoked in an ambiguous (and never clarified) phrase like “the New Jerusalem.” Some of America’s most potent icons are on display in these opening shots of the film: the 360-degree helicopter panorama around the Statue of Liberty’s crown, the swoop across the water to the Battery, Wall Street, and wincingly, the World Trade Center, still 13 years from its destruction. Working Girl was released during the final days of Ronald Reagan’s second term in office, and the astonishing explosion of prosperity in the free-market countries of the world radiated outwards from its epicenter on Wall Street, where Tess McGill toils in low-ceilinged obscurity. Nichols says that he imagined the film’s opening as a “combination of immigrant and slave ship image.”6 David Denby calls the crossing of New York Harbor during the film’s titles “a momentous rite of passage” and argues that the film “celebrates the yearning to belong.”7 Nichols has long commented on the act of immigration as one of the great exercises in conformist survival: “[T]he key was […] the immigrant’s ear: […] they have to learn what’s happening very fast and sound like that.”8

Tess has been working avidly to improve her inherited station among the working class of Staten Island. She rides the ferry daily with her best friend, Cyn, the only woman on their commute with bigger hair. The hair is a superficial compensation, a way for two socially insignificant people to stand out in the throng, yet as the ferry disgorges them, the wide shot often loses them in the sidewalk throng. Tess, who put herself through five years of night school to complete her degree “with honors,” remains relentless in her commitment to self-improvement. Trying to angle Tess into skipping her latest night class (on speech elocution), Cyn wonders in a thick New York accent, “Whaddya need speech class for? You tawk fine.” Altering her elocution will put distance between herself and her life with people like Cyn, who becomes increasingly disapproving as Tess assumes the airs of Manhattan. (By film’s end, though Cyn is Tess’ first call-out from her new office, one wonders how many more phone calls remain in the future of this friendship—do Tess and Jack Trainer share anything in common with Cyn and Tim?) It isn’t Cyn and the other salt-of-the-earth working men and women on Staten Island that Tess objects to, however; rather, it’s the condescension of the Manhattan power elite that has her crazy, knowing she “could do a job” (as she tells Olympia Dukakis in the Petty Marsh personnel office) if only given a chance.

In Working Girl’s title sequence (and several subsequent returns during the film), Tess McGill (Melanie Griffith) rides the ferry from blue-collar Staten Island to Wall Street. These crossings mark the liminal space she occupies as a dreamer of upwardly mobile dreams (Cinderella meets Horatio Alger) in dog-eat-dog New York at the end of the Reagan administration. The film ends with another grand shot of New York Harbor, but Tess’ victory of assimilation has now firmly entrenched her in the financial district, where she is no longer visible—she has been consumed within the uniformity of the concrete canyons.

The introductory scenes in Manhattan clarify Tess’ sense of gendered entrapment. For her bosses, Turkel and Lutz (James Lally and Oliver Platt), Tess is not quite a nonentity because she’s eye-candy, but as a colleague, she’s worthy only to fetch coffee and, in time of deepest need, toilet paper. They do not take seriously her requests to be sponsored for the “Entrée Program”; instead, they “pimp” her out to randy colleagues like Bob from Arbitrage (Kevin Spacey) whose swinish intentions are evident from the moment he picks Tess up in a company limo equipped with cocaine, and porn videos where the training tapes should be. After Tess retaliates by insulting Lutz on the commodities ticker, the personnel officer cautions Tess, “You don’t get ahead in this world by calling your boss a pimp.” To her checkered history at Petty Marsh (she’s gone through three bosses in six months), Tess can only assert, “Wasn’t my fault.” Even if we’re inclined to believe her, we’re aware of the overwhelming force of patriarchal practice she’s up against in rejecting business as usual. This is the way this game is played. Offering her a last chance, Dukakis’ character assigns Tess to a different kind of boss than any of her previous executive administrators: Katharine Parker (Weaver).

At first glance, Katharine is everything Tess would like to be. She’s smart, assertive, stylish, able to stop a male colleague’s forward pass and instead turn it into her own strategic offensive. At the meet-and-greet Katharine throws for herself, Tess watches in awe when an oily colleague’s advances on Katharine stray from the professional to the personal, and Katharine deftly makes herself the hunter rather than the hunted: “You get me in on the Southeast Air divestiture plan,” Katharine says, shrugging off his hand, “and I’ll buy you a drink.” Although intimidated and depressed that she is a couple weeks older than Katharine, Tess takes seriously Katharine’s Pygmalion overtures to mentorship. Early on in their relationship, Tess is called into a planning meeting for the meet-and-greet party. A colleague of Katharine, Ginny (Nora Dunn), has made some forceful suggestions about the catering, and Katharine makes a show of having her repeat the ideas for Tess to transcribe. Tess interjects her suggestion to replace the usual tidbits with dim sum, citing an article she’s recently read in W magazine. Ginny expresses skepticism about Tess reading W, but Tess says, “You never know where the next big idea will come from.” When Katharine responds readily to Tess’ suggestion, it may feel to Tess as if her boss has empowered her, but the reality of the exchange has been a subtly encoded demonstration of Ginny’s diminished potency. Ginny is left to reclaim what power is left to her in the room, sniping at Tess that dim sum hardly qualifies as a “big idea.” Katharine’s praise of Tess as the meeting breaks up is awkwardly patronizing: “Dim sum, Tess. I like it, contribution-wise. Keep it up.” With such faux-laudatory power moves, Katharine is intent on pumping Tess up while keeping her down.

Later, as Katharine prepares for her ski weekend, Tess is literally brought to her knees before Katharine, buckling her boss’ feet into bright red ski boots, Katharine’s preferred color as a strategy of inflamed display: she’s a “working girl,” too, her sexuality opening rather than closing the doors because she’s willing to titillate her way to what she wants. Nichols and his longtime editing partner Sam O’Steen (working his ninth of Nichols’ ten feature films) alternate up-angle shots of Katharine with down-angle shots of Tess to solidify the understanding both women have of their respective places in the scheme of American corporate culture. Katharine is a player, and the psychology of corporate gamesmanship seeps into her diction about her personal life. The ski weekend, she allows Tess to understand, is about another kind of deal, one in which she has orchestrated all the details: “We’re in the same city now. I’ve indicated that I’m receptive to an offer. I’ve cleared the month of June.” Thus the way has been made clear for Jack Trainer’s merger proposal. Tess has no sense of the manipulative properties of relationships except when dealing with men like Bob from Arbitrage and Mick, her boyfriend, both of whom see her purely as a sexual commodity who might be capable of answering phones between bouts of sex, and so she guilelessly asks, “Well, what if he doesn’t pop the question?” Katharine waves away her doubt: “I really don’t think that’s a variable. Tess, you don’t get anywhere in this world by waiting for what you want to come to you. You make it happen.” Jack is, in the contextual parlance, the very essence of a “hot commodity,” much as Katharine knows herself to be, and as Tess comes to see herself. This is the function of all the hot bodies on display in Working Girl: their vocational and social marketability is in direct correlation to their factor of physical attraction as well as their professional acumen. When Jack and Tess meet, they’re able—barely—to keep their hands off each other until the Trask pitch carries. With the deal sealed, they can no longer hide their sense of shared qualification: they’ve earned each other, equally hot commodities to one another in boardroom and bedroom. On a different scale of social commodification across the harbor, Doreen has strapped herself onto Mick as Staten Island’s version of upward mobility, orchestrating her own brand of hostile takeover.

“Watch me, Tess,” Katharine says. “Learn from me.” The offer may sound like generous mentorship, but it is actually a fairly naked maneuver to reinforce her potency; Denby writes, “Katharine really is pure actress, a faker who has perfected the appropriate corporate-female style of ‘candor.’”9 Tess takes the command to heart, and when Katharine is conveniently indisposed due to her skiing accident, Tess seizes the opportunity much as Katharine would have, had their roles been reversed. Working Girl offers Cinderella the keys (or security-code combination) to the palace; on a visit by Cyn to Katharine’s brownstone, the two working girls watch in reverence as Tess throws a switch that lowers the entryway chandelier for dusting. Simon’s “Let the River Run” goes through as many permutations over the course of the film as Tess herself, and Nichols and Rob Mounsey, the music scorer for the production, dress up the chandelier scene with a treatment of the song on pipe organ, as if there could be no more formal signifier of arrival than to command a remote-controlled chandelier in one’s vestibule. The film does not hide the materialist longing of its heroine, and the film’s box-office success is due to keeping the ironic undertones of skepticism about capitalism accessible but not aggressively deconstructionist. Tess’ initial visit to the brownstone is, in essence, child’s play-pretend: she sits at Katharine’s desk, listens to Katharine’s plummily intoned messages on the Dictaphone, works out on Katharine’s exercise bike, applies Katharine’s perfume and makeup at Katharine’s vanity, looking at herself in Katharine’s mirror. Indeed, she’s looking at herself applying Katharine’s blusher as she mimics Katharine’s pronunciations when she learns a new dimension of Katharine’s skill set: duplicity. On hearing Tess pitch her idea for a major deal with Trask, Katharine’s implicit allegation is that Tess has misappropriated someone else’s intellectual property: “No chance you overheard it, say, on the elevator?” When Tess immediately rejoins, “No. No way,” Katharine offers an insultingly literalist reassertion of the same question (“Somewhere?”)—as if Tess has used the loophole of not having overheard the idea on the elevator to demur. Katharine’s strategy in these accusations is twofold: to cow Tess into questioning her own agency as a potential market analyst and to learn whether any genuine authority is attached to the Trask proposal. Satisfied that the idea is merely Tess’ makes it fair game for her to poach, though Tess, as she becomes a more accomplished student in the arts of duplicity, would certainly have been able to read unintentional praise in Katharine’s twice-suggested accusation that her idea has originated in a third party. When Tess hears, “Hard copy on this from my home computer. Do not go through Tess,” she learns a great deal about “the rules” of the game, and the patronizing “Watch me, Tess. Learn from me” refrain takes on an unintended irony. Griffith’s face in empowered, low-angle close-up is steely, clamp-jawed: “Two-way street,” she says, echoing another of Katharine’s often repeated and clearly insincere exhortations. And so, equipped with a complicated, comic set of performed roles she must juggle, Tess goes to work. The irony is, however, that she cannot close the deal she makes (either with Trask or with Jack) on her own, and she will at some point have to confess her own duplicity. Katharine must play an instrumental role in sealing both deals, as she is unable to stop her petty power-playing in the film’s climactic scenes.

Working Girl is at its least convincing as a glimpse inside the art of the deal. The fantastic dimensions of the narrative extend to the power-grubbing effrontery of Trask’s gatekeeper, whose sneering pleasure in refusing Jack and Tess’ proposal is trumped (pun intended) by a mysterious phone call from Trask himself, commanding the deal to be set in motion. The scene ends with Harrison Ford, as Jack, eyeing possible hiding places for hidden cameras and the gatekeeper’s assurance that Trask “knows everything.” The scene plays, in other words, as commerce made mystical. A god has spoken, and some scramble for cover, while others smile with a grace bestowed. Jack Trainer, a seasoned professional (despite his recent “slump”) appears as astonished by it as a neophyte like Tess. In fact, they only have this meeting because of crashing Trask’s daughter’s wedding, a barbaric abuse of opportunity that ought to have made Jack and Tess lepers at Trask Industries, if not across the length and breadth of the Financial District. If there is something magical about Trask, a sort of fairy-godfather of this Cinderella retelling, there is something undeniably magical inherent within Tess, as well—for all her earnest preparation and left-field ability to see lucrative connections between Fortune features and Daily News gossip, Tess has the magic of sex appeal, and she understands this. As she tells Jack when they meet cute over tequila (and Valium) at a closing party the night before her initial pitch at Dewey Stone, “I have a head for business, and a bod for sin.” Jack approves of the package: “You’re the first person I’ve seen at one of these damn things that dresses like a woman, not like a woman thinks a man would dress if he was a woman.” Jack’s highest praise of Tess to Trask, on the other hand, is simply, “She’s your man.” But a man couldn’t have charmed Trask on the dance floor at his daughter’s reception (nor could most women). For that particular job, it helps to be Melanie Griffith. As one might expect, in Working Girls, sex sells.

With her transformation from Staten Island broad to Katharine Parker wannabe, Tess’ old circle can’t help but notice her pretensions. Attending a party for Cyn and her fiancé, Tim, Tess butts heads again with Mick, who tells her morosely, “You look different.” Without enthusiasm, he adds that she looks “Classy.” The word has all the pejorative undertones that an ambitious blue-collar entrepreneur like Mick would be threatened by; despite his own ambitious reach, she’s clearly reaching even further. His futile proposal, coming so quickly after his having been caught with Doreen, is as audacious in its way as Tess crashing the Trask wedding with a proposal of her own. But Working Girl is Tess’ Cinderella story, not Mick’s, and the fantastic clings to her initiatives, while we see Mick in a grittier sort of realistic success, with the less glamorous Doreen as his partner in the new boat business. Mick’s transformation via American dream retains the boundaries of water—he will remain a Staten Island boy who will never be closer to Manhattan than its harbor. Tess’s dream is complete; she aspires to and, in the narrative’s wish fulfillment, becomes “classy”—a word uttered only by the underclass.

Tess flees Staten Island and Mick’s proposal with his command that she get her “priorities straight” ringing in her ears. The next time we see her, she’s attempting, simultaneously, to be two people: “Tess McGill of Petty Marsh” and “Miss McGill’s secretary.” Cyn watches her performance, unimpressed: “First of all, look me in the eye, and tell me you’re not thinking, even in your wildest dreams, Mr. Briefcase-Let’s-Have-Lunch is going to take you away from all of this.” Cyn can’t even imagine what Tess has been dreaming: Cyn thinks all this effort of night school self-improvement has just been to nab a higher-class husband. Cyn assures Tess, “You’re gonna get your heart stomped, just like you’re stomping Mick’s.” She functions as Tess’ voice of reified resignation: “Look, all I’m saying is, if you’re so smart, why don’t you act smart?” The irony is that this is literally the project upon which Tess has embarked: she’s play-acting a role as a Katharine Parker-style desk warrior. Assuring Cyn she knows what she’s doing, her rationale is a near-paraphrase of Benjamin Braddock’s outraged summation of social proscription to Elaine Robinson at the drive-in on their date in The Graduate: “I’m not going to spend the rest of my life working my ass off and getting nowhere, just because I followed rules that I had nothing to do with setting up.” In The Graduate, Benjamin concludes that “no one” sets up the rules—“they make themselves up,” an even more radical understanding of reified proscription than Tess’ perspective on patriarchal exploitation. When the phone rings and, sitting at Katharine’s power desk, she reflexively defaults to her imagined sense of power (“Tess McGill’s office”), her defiance of the rule-makers that have pre-ordained her status is instantly deflated by Katharine’s startled correction. “No,” says Tess apologetically, “Of course it’s still your office.” Cyn piles on; as Tess listens to Katharine’s orders entering through her phone ear, Cyn provides a parable for her free ear: “Sometimes I sing and dance around the house in my underwear. Doesn’t make me Madonna. Never will.”

Cyn’s reference to the Material Girl is particularly apt, given Madonna’s persona as a shape-shifting paragon of empowerment through reinvention, Madonna Louise Ciccone slipping her working-class roots to become a perpetual pop icon. Madonna is a kind of patron saint of canny self-commodification, always two steps ahead of the prevailing powers of her objectification, manipulating the manipulators. She would not have been out of place as the soundtrack’s choral commentator on Tess’ liminal passage from Staten Island ethnicity (a McGill stuck with her “Mick”) to Manhattan player, apprenticed to a Trainer. Yet Carly Simon is an evocative choric presence as well, her career path working some of the same pop-exploitation territory Madonna would work a decade later: no female singer-songwriter of the 1970s more overtly sexualized her image than Simon in a series of frankly erotic album-cover portraits that interpreted her aggressive/confessional song-narratives (“You’re So Vain”; “You Belong to Me”). As Nichols used variations on Simon’s song, “Comin’ Around Again” as both vicarious and ironic non-diegetic counterpoint to Rachel Samstat’s travails in Heartburn, so Nichols uses Simon’s “Let the River Run” to promote the sensation of a dreamer’s self-actualization.

Tess’ reference to “rules” in her apologia to Cyn receives re-definition in the second half of Working Girl, when Katharine returns to Manhattan. Tess is immediately relegated to Cinderella-like chores, schlepping Katharine’s suitcases and running her errands. The montage that immediately precedes Katharine’s arrival includes the shot of Tess vacuuming, framed in a doorway like a life-size poster-portrait depicting the eroticized fantasy of patriarchy, in which the “bod for sin” is also good for menial servitude. (Sam Mendes quoted the image in American Beauty, his 1999 Academy-Award winner for Best Picture and Best Director, with Annette Bening as the object of desire domesticated, feverishly sweeping the carpet of one of her realty properties in her lingerie.) When Tess arrives with Katharine at the brownstone, it is shining—but Tess has “carelessly” neglected to turn off Katharine’s computer. The screen reveals Katharine’s memo about Trask intended for Jack Trainer, left visible by Tess as a sub-conscious accusation of her boss (otherwise, considering that the Trask deal is happening later that same day, Tess’ carelessness is an air-headed error of colossal proportions). When Katharine sees the memo, she improvises, unfolding a story of Jack Trainer and unfounded allegations of ethical misconduct that ironically parallel her own misappropriation of Tess’ idea (she can’t know that Tess has heard her memo to herself on her Dictaphone and thus already has the accurate back story on the Trainer memo). “See, “ Katharine says, “Jack got burned once. He was accused of stealing a plan for taking a company private. He’s very sticky about the ethics of reviewing other people’s formative strategies. He wouldn’t have looked at [the Trask idea] if I’d said it was from a colleague, and I couldn’t very well say it was a secretary’s notion.” These last distinctions, between “colleagues” who have “ideas” and “secretaries” who have “notions,” eliminates any residual qualms Tess might have had about what she’s been doing while the boss was away. Katharine’s rapacious exploitation of Tess makes the treachery of louts like Turkel and Lutz look like the relative amateurs they are. Where once she’d exuded to Mick, “It’s so exciting. I mean, she takes me seriously. […] There’s none of that chasing-around-the-desk crap. And it’s like she wants to be my mentor, which is exactly what I needed. I mean, I feel like I’m finally getting somewhere, Mick,” now Tess must come irrevocably to terms with Katharine’s sense of entitled ownership of Tess and whatever might emerge from her. In Katharine’s eyes, Tess has no more right to her “idea” than to calling Katharine a “colleague.” Intellectual property is relativized by hegemony: the best idea in the hands of the powerless is roughly equivalent to no idea at all.

Compounding her “error” in leaving the memo open on Katharine’s computer, Tess “forgets” to collect her planner when she dashes from Katharine’s house after delivering a pharmacy order, leaving ample evidence for Katharine to assemble to understand Tess’ scheme. The film offers no definitive interpretation of these apparent gaffes, but Tess’s predicament will not end with the finalizing of the Trask deal. She must discredit Katharine if she is to restore some of the credibility she will inevitably lose after confessing, as she must, that in sleeping with Jack and making a deal with Jack and Trask, she has fundamentally deceived them. If it is accidental that she allows Katharine a way into the proceedings of the deal, it is a fortuitous stroke of luck; if it is intentional that she offers Katharine clues to what she has been up to during her boss’ absence, it is a brilliant stroke of strategy. Inevitably, Katharine must roar her outrage, and Tess must let her—but she would also know that she has done her homework on the Trask deal, and Katharine has not; its intricacies and Katharine’s arrogant appropriation of the deal as her own without having earned its intellectual property still remain to undo Katharine and restore Tess as capable and hungry enough in a man’s world to find the unorthodox side entrances—a crashed wedding, an assumed position—to command a hearing. It’s possible that Tess only appears careless, and has in fact set Katharine up to hang herself on her own entitlement.

Working Girl is laden with mirrors and mirror-surfaces. As Katharine has spun her story at Tess, she’s reflected in a mirror behind her, visually depicting the traditional cinematic trope of split identity or, more specifically in this case, two-faced deception. Yet no one in the film is reflected in more mirrored surfaces than Tess. The night of her birthday, alone with Mick, she laments she can’t wear any of his pointedly erotic gifts in public; it’s the first of many times we see her modeling a man’s fantasy of women’s lingerie, with peekaboo panels and dangling garter straps, and her reflection in the mirror sets up her divided identity as Mick’s girl and Wall Street’s girl. With Cyn at Katharine’s house, she’s back in garters again as she holds up a series of outfits to decide what to wear to surprise Jack Trainer at the party the night before their meeting, and the cocktail dress she eventually chooses is as stunning as it is stunningly out of place among the soberly masculine female couture decorating the rest of the women—like, for instance, Katharine’s colleague Ginny, from whom Tess flees as if at the approaching stroke of midnight, to escape being revealed as a fraud. After leaving Katharine’s house (leaving behind the incriminating details recorded in the planner), Tess pauses to appraise herself in the lobby of Trask Industries, choosing the mirrored surface of the brass Trask plaque; Griffith’s prominent jaw sets with professional resolve that comes with playing her new role, as a scheming corporate deal-maker whose “two-way street” ethics make her appropriation of Katharine’s status and contacts justifiable once Katharine has opened the taboo door by appropriating her idea. All these reflective doublings serve to remind us that the women in particular are held by patriarchy in the double bind of their corporate gender bending, where the narrative’s highest praise from its princely hero is “She’s your man.”

In Working Girl, the Bad Girl is punished and the Good Girl is rewarded. More important, men preside over the adjudication of their cases and are the primary beneficiaries of all profits the women create. If Working Girl is Tess’ fantasy of class climbing and gender empowerment, it’s a fantasy that reverently respects its limits. While it may question the “rules” and rule-makers, it is quite comfortably recuperative on its surface. In the climactic showdown at Petty Marsh, Tess has cleaned out her desk, sobered by the collapse of a fantasy Cyn had warned her was bound by reified determinism to fail, and in the lobby, Tess falls even farther, her box of personal items jostled to the floor in the scrum at the elevators. But Jack lowers himself swiftly to his knees to help her, and his position as he speaks to her is as the wronged partner, both professionally and personally: “Just one thing: was you and me just part of the scheme, too?” Tess resignedly poses the question they all understand, from lowly cogs like Cyn to small dreamers like Mick to the fully entitled like Katharine and Jack and, at the top of the pyramid, Trask himself: “If I told you I was just some secretary you never would have taken the meeting. […] Can you honestly tell me it wouldn’t have made a difference?”

The narrative has brought them both to their knees, but Tess reminds Jack and us that there remain gradations of gendered powerlessness. Earlier, Jack has confessed to Tess his reified anxiety about the atavistic world in which they work: “One lost deal is all it takes to get canned these days.” He spins a small morality tale about the little pieces of tape stuck one on top of another corresponding to the phone lines at his command on his desk—“new guys over the names of old guys, good men who aren’t at the other end of the line anymore, all because of one lost deal.” The dehumanizing meanness of such an environment reduces Jack physically: in a film that routinely presents Harrison Ford as beefcake, this scene allows him to look weak, anxious, diminished, a speck of bread from his sidewalk sandwich stuck to a corner of his mouth. The unmasking of his partner at the boardroom table would have been devastating had Katharine decided to ruin both Tess and Jack, but she still fancies Jack as her boy-toy, and so she is content to command, “Jack, just trust me and sit down.” Where earlier in the proceedings, the salutations around the table began with “Gentlemen, and”—nodding in Tess’ direction—“ladies,” when Katharine waits for Tess to leave, autocratically reconvenes the walk-through of the deal’s particulars, and then wisely hands the meeting back to Jack (because she has no idea about the nature of the deal), Jack’s salutation to the assembly is less nuanced: “Well, gentlemen, the players may have changed but the game remains the same, and the name of the game is ‘Let’s Make a Deal.’” It’s not Jack’s finest moment. He’s content to type Katharine with the rest of the men (seeing through her calculated ruse of weakness on her crutches). More important, he has just done to Tess precisely what he earlier abhorred about corporate culture: after commodifying her “bod for sin” by seducing her upon their first meeting with a deceptive concealment of his own identity, he manages now to exploit her “head for business,” reaping the fruits of her idea. He’s stuck a piece of tape over Tess. There’s a sense in which his joining her on her knees is about his recognition of this, regardless of his expressions of injury. The “game” and its rules have consumed him, and this has not summoned his best behavior.

While Katharine has become a “man” in these climactic scenes, she retains a woman’s innate sense of power inequity that must constantly be managed. Her feminine dizzy spell in the Trask boardroom may be the most blatant advertisement of her gendered status, but her response to Tess in the elevator lobby is as cliché a moment, this time the trope of the catfight for a man (Trask as much as Jack). Weaver’s statuesque six-foot frame looms over Tess and Jack on the floor, and Katharine piles on, accusing Tess of attempting to steal additional files and the ideas they contain, as well as her fiancé. The best Tess can manage from her diminished position is to call Katharine “bony,” a contrast to her “bod for sin” with its unmistakably generous curves; the insult is puny and ill timed and makes no impact on the players. She hasn’t the spirit left for a catfight, but she rallies by mining her “head for business” and manages to shake Trask’s confidence with her reference to “the hole in your deal.” Now she has Trask’s attention, and he deftly slips from Katharine’s elevator just before it departs. By the time Katharine next sees Trask, his confidence in the deal has been restored; now it is Katharine he doubts. Katharine attempts a coup de grâce, dismissing Tess’ pretentions to qualification: “Oren, we really don’t have any more time for fairy tales.” But she is out of luck, because that is precisely what Working Girl has always, unapologetically, been: a reified fairy tale of circumvented rules. Only one of the two women is able to articulate the deal’s “formative strategy.” Katharine, the mannish (“bony”) working girl is ruined, while Tess, the hungry operator with the “bod for sin,” is rewarded with an “entry-level” position at Trask. Overpeck writes, “Katharine’s comeuppance draws attention to her lack of femininity. By comparison, Tess’s strength is her ability to retain her femininity in the corporate world.”10

Like Jack, Trask appears mystified by Tess’ strange and apparently self-defeating behavior: “Why didn’t you tell us all this in the boardroom that day?” That these supposedly intelligent men can ask such questions may be the most unrealistic element of the whole fantasy. In yet another instance when a Mike Nichols character temporarily sounds as if he or she has just stepped from the script of Catch-22, Tess argues, “You can bend the rules plenty once you get upstairs, but not while you’re trying to get there, and if you’re someone like me, you can’t get there without bending the rules.” Thus the narrative returns to “the rules,” the auteur preoccupation of Nichols’ career. The film has made a great fuss in hanging the contours of its narrative on ethical and unethical behavior, but concludes with an acknowledgement that opportune rule breaking is one of the most important rules of the culture.

The film doesn’t end on this irony, however. Rather, we’re given the opportunity to see Tess’ wish fulfilled. Jack packs her a box lunch in a child’s parody of a Rosy-the-Riveter lunch bucket, and Nichols sees this as “a dream of equalness” in which there might be “far more future for her than Benjamin [in The Graduate] because she and Jack […] have the real beginning of a life together.”11 At Trask, she must endure a last role-reversal, this time with her secretary as the usurper. Alice Baxter (Amy Aquino) is not quite as ostentatiously big-haired and cosmeticized as Cyn and the rest of the Petty Marsh pool, and while she gently and apologetically corrects Tess about their stations (Tess defaulting to having misunderstood Trask’s definition of “entry-level”), she also coolly corrects her about her own status: “If it’s okay, I prefer ‘assistant.’” Tess begins the redress of her sustained abuses in reviewing her expectations of Alice: “I expect you to call me Tess. I don’t expect you to fetch me coffee unless you’re getting some for yourself. And the rest we’ll just make up as we go along.” On a much more modest scale, this is Alice’s fantasy come to life, too; Tess’ allusion to making up their roles foregrounds fantasy in women’s reverse conspiracy against the cabal of patriarchy.

Tess’ first call from the privacy of her office is not to Jack—it’s to Cyn, and Cyn’s response is to rally the floor at Petty Marsh to a frenzied celebration that one of their own has achieved what amounts to a prison break. They are cheering for a friend but also for a fantasy; earlier, up on Katharine’s floor at Petty Marsh when Tess is hired on the spot by Trask (who vows in the same autocratic breath to ruin Katharine), Tess and Jack kiss in full view of the dealmakers and the Petty Marsh secretarial pool, who react with sighs and applause—a veritable movie audience consuming the latest Hollywood confection. Can such things happen beyond “the movies?” In Working Girl, we watch it happen—but that’s the point: it’s a Hollywood fairy tale that deconstructs itself while delivering dependable genre rewards to an audience that was happy to lap them up, more than doubling the studio’s investment in domestic box-office receipts alone. As in The Graduate, the mass audience is largely ignorant of irony in its sweet-toothed consumption of genre’s confections.

The film’s penultimate shot is of Tess on the phone with Cyn, captured from the air outside her office window. The slow zoom out gradually encompasses a grid of identical glass-and-steel offices in which, only by the greatest concentration, can we remain focused on where Tess is.12 This shot dissolves into the final, gorgeous helicopter shot, lingering near the crown of the Woolworth skyscraper, of Tess’ building, in which Tess’ office is now an indistinguishable gray block in a receding labyrinth of office blocks that eventually resolves, as the helicopter drifts out over the harbor, into the southern tip of Manhattan, its western contour dominated by the Twin Towers. Subsequent events notwithstanding, there is ambiguity in the triumphalism of this final image (with Simon’s voice celebrating “the New Jerusalem,” which is “now an ironic counterpoint to Tess’s new anonymity,”13 in which individual dreams are subsumed within a yielding to the corporate whole.14 If Tess can stand to make it there, she can make it anywhere, living with the anxiety of “the rules” and the omnipresent fear of becoming a mere name on an old piece of tape with newer names unceremoniously pasted on top. Working Girl gives its audience exactly what it wants, then asks us to consider if that’s wise.