Advice on equipment is given later in this chapter, but if you are new to bird photography (or even photography itself), then a short, down-to-earth description of how to get the best out of your camera gear might be useful.

The basic effects on the image of varying depth of field and shutter speeds are not covered in this chapter, as these are demonstrated and explained in the main part of the book. Studying the images and their captions should help you to get a feel for their general use. Broadly speaking, unless you are trying to achieve a specific effect, most bird photography is done at or near the maximum aperture of the lens to allow as fast a shutter speed as possible, minimizing camera shake and freezing any movement made by the bird itself. Putting these aspects aside, we are really only left with exposure and focusing to deal with when it comes to getting to grips with the basics of how to use your camera when photographing birds.

EXPOSURE

More than any other subject, exposure seems to confuse many people. Digital makes life easier, as I explain later, but a good grasp of the fundamentals of exposure will help you understand what to do in different lighting conditions.

Three variables that you control are used to determine the correct exposure. These are:

Aperture | This sets the size of the hole in your camera lens. The bigger the hole the more light you let through. Confusingly, the aperture values are counter intuitive, as the smaller the number the bigger the hole. Thus f4 lets in twice as much light as f5.6, which again lets in twice as much light as f8. Note from this that f4 lets in four times as much light as f8 and not twice as much as you may think.

Shutter Speed | This determines how long the camera shutter will be open to accept the light through the aperture of the camera lens when you take a picture. Shutter speed settings are simple as they refer to the time the shutter is open. Thus a setting of 1/500 indicates that the shutter will be open for 1/500th of a second. A setting of 1/1,000 is twice as fast as 1/500, so will let in half as much light as it is open half as long.

ISO | This used to refer to the film speed, but with digital you can set it to a whole range of values. The higher the number, the quicker the camera will record the image. The numbers are simple. ISO 400 is twice as fast as ISO 200.

Let’s deal with the ISO setting first. Generally speaking, the higher the ISO setting the more noise you will get in your picture, so the poorer the quality. Most bird photographers use either 200 or 400 ISO, but the quality of pictures at higher ISOs is constantly improving, and in the future we will be able to use much higher values. For now let’s set the ISO at a constant ISO 400. That done we can forget it and move on to the other variables.

Aperture and shutter speed work together to allow a certain amount of light through to the cameras sensor. A bigger aperture lets in more light, so a faster shutter speed will be required to limit the amount of time the sensor is exposed to the light. Thus 1/500th of a second at an aperture of f5.6 will produce the same exposure as 1/1,000th of a second at f4 or 1/250th of a second at f8. The total amount of light reaching the camera’s sensor is the same in each case. At 1/1,000th of a second at f4 you have a lot of light for a short time. At 1/250th of a second at f8 you have a quarter of the light, but the sensor is exposed for four times the amount of time.

Assuming that your ISO is always set the same, your sensor will require the same amount of light to make the correct exposure. The brightness of the light available plays a significant role here, as to make up the total amount of light required for the exposure will take a lot longer on a cloudy day than on a sunny one. An exposure of 1/2,000th at f5.6 may be correct when a bird is in bright sunshine, but 1/125th at f4 might be required as dusk approaches on a cloudy day. The total amount of light required for exposure remains the same, however. It just takes longer to collect enough of it when it is dull than it does when it is bright.

We have established how exposure works and what we use to control it, but why bother when the camera has automatic exposure modes that work it all out for you? Auto exposure is a good starting point, but it fails in many situations because it is based on a key assumption – that the world is a uniform mid-tone (often referred to as 18 per cent grey). This means that it calculates the amount of light it requires for an exposure assuming that the image it is capturing is of an even mid-tone. However, in many situations the overall exposure will not be mid-tone, so the exposure will not be correct.

In bird photography, one approach that works well is to ignore the background and expose for the bird. If your main subject is well exposed, the picture is much more likely to work. When, for example, you are photographing a bird in flight, a blue sky generally tends to be brighter than mid-tone, so the camera’s exposure system tends to underexpose it. This makes the sky a nice deep blue colour, but the bird itself is likely to be underexposed. When photographing birds in flight against any background it is always best to set the exposure for the bird manually, because when tracking the bird the background could well change – for example if the flying bird passes a white fluffy cloud, which will play havoc with the camera’s exposure meter. See also the examples of Grey Herons for the effect of backgrounds on exposure.

One of the most common problems arises in the exposure of white birds or birds with large amounts of white on them. If set to a mid-tone exposure, the white areas of the bird will almost certainly be overexposed. A white bird usually requires a full stop less exposure than a ‘normal’ bird. For example, when photographing in Britain on a bright, sunny day, my standard exposure would be 1/2,000th second at f5.6 for something like a Mallard in flight. In the same conditions, when photographing a swan in flight I would expose at 1/2,000th second at f8 – i.e. I let half as much light into the camera for the swan as I do for the Mallard. If I let the same amount of light in as I would for the Mallard, this would be too much for the sensor to handle and the swan would be overexposed. In the swan picture the background will be darker than the same background for the Mallard, but as long as the main subject is correctly exposed you can get away with this.

These effects can clearly be seen in the next two images, taken in similar conditions during a British winter. Both are correctly exposed, but the swan picture required half as much light as the Mallard picture. The water in the swan picture appears darker, as explained above – it actually looks good, though it is a stop underexposed.

MALLARD

MALLARD

1/2,000th @ f5.6

WHOOPER SWAN

WHOOPER SWAN

1/2,000th @ f8

CHECKING THE EXPOSURE WITH DIGITAL

As mentioned at the start of this chapter, digital has made the whole process of getting the exposure right easier. A digital camera’s meter will get things wrong just as easily as a film camera, but the camera can provide you with instant feedback, allowing you to check whether the exposure is correct immediately after you have taken a picture. You cannot determine whether the exposure was correct from the little picture on the back of the camera. However, by setting the highlight alert feature on, you can tell if any areas of the image are overexposed, as they will blink on and off continuously. Overexposed highlights are one of the biggest problems, so this is a useful feature.

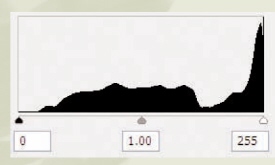

Of course, this feature only deals with overexposure; for a more complete review of the exposure, you need to look at the histogram that can be displayed with every image on the back of the camera. The histogram is a graph showing how the light used to expose the image is distributed. The higher the ‘mound’ on the graph, the more light has been recorded at that particular intensity. The mid-tone is (unsurprisingly) in the middle of the graph. Anything to the left of the mid-point is getting progressively darker until the left edge, which is black. Anything to the right of the mid-point is getting progressively lighter until the right edge, which is white.

If you have overexposed the image there will be a sharp peak on the right-hand side, and if the image is underexposed there will be a sharp peak on the left-hand side.

THIS HISTOGRAM SHOWS AN IMAGE THAT HAS BEEN UNDEREXPOSED. THE LARGE PEAK UP AGAINST THE LEFT EDGE OF THE HISTOGRAM INDICATES THAT MUCH OF THE DARKER AREAS OF THE IMAGE HAVE BEEN LOST AND ARE NOT RECOVERABLE. YOU CAN ALSO SEE THAT THE RIGHT-HAND THIRD OF THE HISTOGRAM SHOWS NO DATA AT ALL, BECAUSE THE HIGHLIGHTS HAVE BEEN RECORDED AS MID-TONES.

THIS HISTOGRAM SHOWS AN IMAGE THAT HAS BEEN OVEREXPOSED. THE LARGE PEAK IS NOW UP AGAINST THE RIGHT-HAND SIDE OF THE IMAGE. THIS INDICATES THAT THE HIGHLIGHTS HAVE BEEN BLOWN OUT AND ARE NOT RECOVERABLE. THERE ARE NO BLANK AREAS TO THE LEFT OF THE HISTOGRAM, SO TO CORRECTLY EXPOSE THIS SUBJECT SOME OF THE DETAIL IN THE DARKEST AREAS OF THE IMAGE WILL HAVE TO BE SACRIFICED WHEN THE IMAGE IS CORRECTLY EXPOSED. GIVEN THE CHOICE OF KEEPING EITHER THE HIGHLIGHTS OR THE SHADOW DETAIL, ALWAYS KEEP THE HIGHLIGHTS.

Generally speaking, you want all of the information to be recorded and not touching either edge. Of course, it is perfectly possible to achieve this and not have the correct exposure, because the image could still be either overexposed or underexposed and remain within the histogram’s boundaries.

One general rule that many photographers employ is to ensure that the brightest part of the image is close to but not over the right-hand side. This ensures (due to the way that the sensor records the data) that you are capturing the maximum amount of data to make the image as high in quality as possible. This is certainly the technique that I use. As long as no data has been lost, the exact exposure can be set later, when processing the RAW image.

It takes practice to get to the point where you can understand the histogram, but hopefully the following three images, shown with their histograms, will help you get started. All three images were taken on the same day in the same bright sunlit conditions, and the exposure was the same for each of them (1/1,250th sec @ f8). All are correctly exposed, but the histograms are far from alike.

HERE WE HAVE A CLASSIC MID-TONE EXPOSURE, WITH THE DATA BEING SPREAD ACROSS THE HISTOGRAM, PEAKING IN THE CENTRE. BOTH THE BACKGROUND AND THE BIRD ARE ABOUT THE SAME TONE. IF ONLY ALL SITUATIONS WERE LIKE THIS, WE’D HARDLY EVER GET THE EXPOSURE WRONG.

HERE, THE BLACK LINE ON THE BOTTOM OF THE GRAPH EXTENDS RIGHT UP TO THE RIGHT-HAND SIDE. THIS REPRESENTS THE PALEST PART OF THE BIRD AND IF THE EXPOSURE HAD BEEN JUST A LITTLE BIT LONGER, THIS DATA WOULD HAVE BEEN SHOWN PILED UP AGAINST THE RIGHT EDGE WITH THE HIGHLIGHTS BLOWN OUT. THE REASON WHY THE HISTOGRAM LOOKS AS IT DOES IS THAT MOST OF THE IMAGE IS MADE UP OF THE SHADED TREES THAT FORM THE BACKGROUND.

HERE THE BULK OF THE DATA IS TO THE RIGHT OF THE MIDPOINT ON THE HISTOGRAM. THIS IS THE OPPOSITE OF THE PREVIOUS IMAGE, AS THE BRIGHT BLUE SKY BACKGROUND IS BRIGHTER THAN MID-TONE, SO IT APPEARS TO THE RIGHT OF THE MID-POINT ON THE GRAPH. HAD THE CAMERA ITSELF MADE THE EXPOSURE, IT WOULD HAVE PUT THE PEAKS AROUND THE MID-POINT. THIS WOULD HAVE RESULTED IN AN UNDEREXPOSED IMAGE AND THE HERON WOULD HAVE APPEARED TOO DARK.

FOCUSING

I use autofocus virtually all of the time in bird photography, but it is important to select the correct ‘mode’ for the type of picture you are taking. There are usually two modes, one that tracks the subject constantly (AI Servo) and one that doesn’t (One Shot). When trying to follow a subject that is moving around a lot, such as a bird in flight, it is essential to use AI Servo. This will keep (or at least try to keep) the subject in focus as long as you manage to keep it in the viewfinder. When I photograph birds in flight I activate as many of the camera’s autofocus points as possible, although other photographers will swear that you should only use the central focusing point.

One Shot autofocus – to my mind – is not a very good description, because it gives the distinct impression that you can only take one picture at a time, which is not in fact the case. With One Shot, the camera focuses as you ‘half’ press the shutter release, just as it does in AI Servo mode. The difference here is that instead of now attempting to track the bird, the focus point will not change while you keep pressure on the release button.

This is extremely useful, because it enables you to focus the camera on the eye of a bird, then reposition it in the frame without the focal point changing. It only works if the bird is not moving around, but it is the best method of allowing you to compose the image without autofocus wandering about all over the place searching for something to focus on. I only ever use the central focus sensor in this mode – I simply and easily position this on the part of the bird I want to appear the sharpest, before recomposing.

FOR THIS IMAGE OF A RAZORBILL, I USED ONE SHOT AUTOFOCUS BY POSITIONING THE CENTRAL FOCUSING POINT ON THE BIRD’S HEAD AND DEPRESSING THE SHUTTER HALF-WAY TO OBTAIN FOCUS. KEEPING MY FINGER ON THE SHUTTER BUTTON, I REPOSITIONED THE CAMERA TO A MORE PLEASING COMPOSITION AND TOOK SEVERAL SHOTS. IF I HAD BEEN USING AI SERVO MODE WITH THE CENTRAL FOCUS POINT, AS SOON AS I REPOSITIONED THE CAMERA IT WOULD HAVE REFOCUSED ON THE SEA BEHIND. IT WOULD HAVE BEEN POSSIBLE TO SELECT A FOCUS POINT THAT WOULD HAVE BEEN TO THE LEFT OF CENTRE AND ON THE BIRD’S HEAD. THIS WOULD HAVE WORKED IN EITHER MODE, BUT IS A BIT FIDDLY TO SET UP AND WOULD NEED TO BE RESET FOR EVERY NEW COMPOSITION.