The New Pieces

EARS FULL OF SHAVING CREAM AND burning shoelaces.

Those are two of my favorite memories from the 1987 regular season.

On the field it was a little like ’84, where we kind of snuck up on people. We sure didn’t blow anybody away. We couldn’t win on the road, we had two quality starting pitchers, and overall we had just 87 victories. But we played in a weak division, and it was enough to get us into the playoffs.

Once again we had some real characters on that team, the difference from previous years being that the characters also had a little more ability when it came to baseball. Take Bert Blyleven. Some might add “Please” after that, since Bert could drive you nuts.

His main gig was burning people’s shoelaces. One time in ’87, during a game, he crawled all the way under the dugout bench, from one end to the other, and lit manager Tom Kelly’s shoelaces on fire. I thought it was pretty neat to be on a team where a player would feel comfortable enough to do that to his manager. TK would take that sort of thing, but you knew where the line was with him, and you didn’t go over it. But his line was pretty high, as long as you were giving him everything you had on the field.

Bert could be a pain in the ass because every time he’d burn your shoelaces you’d have to put new ones back in, and that took a lot of time. And Bert taught a lot of guys on the team how to burn shoelaces, so you always had to be alert. If they got you, you usually ended up giving the clubhouse guys a couple dollars to put new shoelaces back in. We probably had some of the best-paid clubhouse guys in the league, thanks to Bert and his followers.

Our other main schtick as a team was planting shaving cream in the ear end of the telephone. We did that one all the time. So much, in fact, that you’d often refuse to answer a phone when someone yelled that you had a call. But that would only get the guys doing the trick more determined. So they’d go get our trainer, Dick Martin, to yell out that you had a phone call. Well, when Dick called for you, it was usually important, so you’d let your guard down, run into the trainer’s room, and grab the phone. And get an ear full of shaving cream.

There wasn’t a person in the clubhouse who didn’t get busted with shaving cream. It was stupid, but it kept us loose. And there wasn’t a guy on the team who took it to heart and didn’t have fun with it.

To me, that was a really important reason that we had the success we did in ’87. I’ve always been a big believer in intangibles, and if you’re all pulling the same way—from the front office to the clubhouse guys—I think that makes a huge difference. A successful team can’t have anyone bitching about the front office or the traveling secretary. When you’ve got everyone on the same page within an organization, that gives you a chance to hit your peak. You get just one person off the page, and that makes a difference. I honestly believe one person can pull a whole team down.

Of course, there was more to our success in ’87 than practical jokes. One big reason was that the front office made some major changes before the ’87 season. We got an All-Star closer in Jeff Reardon, a set-up man in Juan Berenguer, a leadoff hitter and left fielder in Danny Gladden, and a top bench player in Al Newman. The new guys fit in, probably better than anyone had a right to anticipate. And as an added bonus, they could play a little bit. That always helps.

As it turned out, Tom Brunansky (left), Kirby Puckett (second from right), Gary Gaetti (right), and I were the right combination of talent needed for the Twins to win a World Series. Courtesy of the Minnesota Twins

The key addition was Reardon. Although I hate it when people blame Ron Davis for our early problems, the truth is we struggled for years to find a closer. Getting Reardon was about the first time we went out and acquired somebody who still had something left, instead of getting someone who was washed up and nobody else wanted. When we acquired Reardon, we immediately had confidence that if we could get a lead into the late innings, we had a shot to win. That’s a huge mind-set for a team to have.

The impressive thing about Jeff is that he struggled big-time the first two months of the season. By late May, he had an ERA over 10.00 and was struggling with his control. As a team, we were under .500, at 21–22. But Jeff kept asking for the ball. He didn’t change a bit, even when he was struggling, and I think we all gained a lot of respect for him those first two months.

Of course, the thing with Reardon is that I don’t think any of us had a read on what was going on inside of him. We called him “The Terminator,” or “Yak,” because of his big curveball that we called a yakker. I always said he looked like Charlie Manson. He was a little spooky looking with that beard and those steely eyes. Charlie Manson probably isn’t a guy you want to be associated with, and I said it just for fun, but he had that look.

Beneath the beard was a guy who was extremely quiet and shy. Nicest guy in the world, but you just didn’t talk to Term much. In fact, that whole 1987 season, I never had a long conversation with him. He always had this little laugh: “heh, heh, heh.” You’d be talking to him, and he’d give you that little, “heh, heh, heh,” and turn and walk away.

A lot of closers are a little different. Maybe a little bit like kickers and punters in football. They have their own routine to get ready for a game, and they keep to themselves a lot.

Later in life, Term ran into some real problems. He had a son who died a few years ago, and after that, Term ran into some heart problems and some psychological problems. I couldn’t believe when I heard the news that he’d been arrested for robbing a jewelry story in Florida. I knew he was a guy who would never do anything like that, and that’s what came out. He was on medication for his heart and depression and it affected his mental state to the point where he apparently didn’t even know what he was doing.

I’m rooting for Term to get his life back in order because he’s a great guy—a very sincere, sensitive guy. He might look like a guy who’s going to grab the neighbor’s cat and squeeze its head off. But Term would be the guy holding the cat and petting it.

Señor Smoke

Have you ever seen those cartoons where you see the bull with a ring in his nose, scratching the ground with his hoof, snorting fire? Every time I see one of those cartoon bulls, I think of Juan Berenguer because that’s what he was like on the mound.

He was “Señor Smoke.” He’d no more than get the ball back from the catcher and he’d be ready to throw it again. He was always jacked up on the mound because he just loved to get people out. I know during the playoffs in ’87 some people felt he was showing the Tigers up with his arm pump, and I hated to see it, but there was nothing you could do about it. That was Juanie just being pumped up—funny, colorful, and a little bit moody. But I loved watching the guy pitch.

One thing that added to Juanie’s persona is that he never really mastered the complete English language. He used to butcher little parts of it. Like instead of saying “son of a bitch,” Juanie would always say “son of my bitch.”

I know firsthand. On one of our road trips during the regular season, our charter landed late, and the team bus got to our hotel in Toronto about 4 a.m. We were going through the hotels revolving door, all of us tired as heck, just shuffling along. I had Juanie going through the door right behind me, carrying his briefcase, like he always did, and wearing one of those funny little Fedora hats. As I was going through the door, I did one of those quick stops, just to see if he was awake. He wasn’t.

His face ran right into the glass door. I looked back, and all I could see was Juanie’s nose, mustache and big teeth planted against the glass. We got out of the door, and Juanie chased me all over the lobby, screaming, “You son of my bitch! You son of my bitch!”

The funniest thing was going down the next day and seeing Juanie’s big nose print still plastered on the revolving glass door.

But what a great guy to have on your staff. Juan would have pitched every day if they let him. One of the classic interviews was Juanie talking after Game 6 of the ’87 Series. The reporter asked Juan if he’d be able to pitch tomorrow, and Juan didn’t hesitate: “I pitch tomorrow. I start tomorrow if they need me.” He was a classic. His arm always hurt him, but he’d throw until it fell off. He loved pitching that much.

Newmie

We picked up Al Newman from Montreal during the offseason about three weeks after we got Reardon. I knew nothing about Newmie, and when he reported to spring training, there was no guarantee he was even going to make the team.

Funny the way things work out in this game. Newmie was in about a five-player battle for the backup infielder spot, and one of his prime competitors was Ron Gardenhire, who we had picked up from the Mets. Newmie had a little more speed and was a little more versatile than Gardy. So Newmie made the team, and Gardy got cut.

Newmie probably cost Gardy a major-league job, but it turned out to be a good move on a couple fronts. Gardy became a minor-league coach, then a minor-league manager, and found his true calling. I think Gardy is one of the best managers in the game today. To me, he’s a lot like Tom Kelly when it comes to respecting the game and emphasizing fundamentals. About the only difference is Gardy is a little more media-friendly.

Newmie became an important part of two World Series championship teams. Not only was he a very good player coming off the bench, he was one of those chemistry guys. Al always had a smile on his face and was always happy just to be wearing a major-league uniform. He had a great sense of humor, and he turned out to be a very good friend of Kirby Puckett and Danny Gladden, the last, but certainly not the least, of the new faces added before the start of the ’87 season.

Wrench

We picked up Gladden in a trade with the Giants just before breaking spring camp. The first time he came walking through the clubhouse door, I gave him the nickname “Wrench.” He looked like he’d just finished doing an oil job and greasing somebody’s car in the parking lot, like Mr. Goodwrench.

It’s hard to know where to begin when you talk about Danny. He was a little troublemaker. He was that kid on the block who would light a fire and burn a garbage can up, and then another kid would get caught for it, and Danny would throw up his hands and say, “I had nothing to do with it.”

He was a big-time instigator on a daily basis—just a ton of little things. Like he’d walk over to you in the clubhouse before a game, and say, “Geez, I heard you had a few too many cocktails last night.” So you’d go find the guy you were out with and say, “Why the hell would you tell Danny I had some cocktails last night?” And of course, no one had told Danny a thing. He’s just trying to stir something up. Every day he was trying to stir something up.

I think Danny was the guy who got TK thinking about giving guys a rest if there was a day game after a night game. Danny over the years got a reputation that he didn’t play on Sunday. It got to be kind of a joke. You’d see Danny out on Saturday night, and you’d think he better slow down. Then you’d remember that he didn’t play on Sundays.

TK learned that was a good idea pretty quick. That was the kind of thing Billy Gardner would never think of. Heck, I made all the bus trips and played every inning of every spring training game with Billy. I just didn’t know anything different. I’m not sure any of us did, until Danny came along.

But Danny had a little fire to him, and I loved the way he played the game. He reminded me a lot of Johnny Castino with his drive. Danny was the kind of guy you hated playing against. He had a little cockiness about him, with that long blonde hair and a little bounce to him when he ran. He was also another guy who was a lot softer than he appeared to be. Danny was fun-loving, but he was also a puppy dog at heart.

Not In Our Clubhouse

Of course, even puppy dogs get angry once in a while. And Danny had a temper, which Steve Lombardozzi can attest to. Late in the ’87 season Lombo got mad about being taken out of a game, and Gladden said something to him in the clubhouse about being a man and accepting things. Well, Lombo stewed on that and ended up driving to Danny’s house and knocking on the door to tell him that he was, indeed, a man. One thing led to another, and they ended up in the backyard wrestling. Danny told me that his daughters were screaming, trying to get their mom, because Daddy was fighting some guy in the yard.

Lombo ended up getting a black eye out of it. But I thought it was pretty manly of Lombo. He didn’t want to bring a problem into the clubhouse, so he went and knocked on Danny’s door. OK, maybe it wasn’t the brightest thing to do. But give them credit: When they got back to the clubhouse the next day, you never knew anything had happened, other than Lombo had that nice shiner. A lot of guys would have had it out in the clubhouse, but that didn’t happen. I’m not saying they were ever best friends, but our clubhouse was always a great place to be.

You just had to keep close tabs on your shoelaces and the shaving cream.

When we got to spring training, the media focus was as much on the so-called Class of ’82, as the writers dubbed the six of us who had been rookies in 1982—Gary Gaetti, Tom Brunansky, Tim Laudner, Randy Bush, Frank Viola, and me—as on the offseason additions. The six of us had never done a thing as a team other than mount a brief challenge in 1984. From the start of 1982 through the 1986 season, the Twins had a record of 359–451, which isn’t much to hang your hat on.

It didn’t take a genius to figure out that this was a make-or-break season for us. Management had surrounded us with some talent, and if we didn’t produce, the Class of ’82 was going to be split up. We’d been in the league long enough that we were starting to make some decent money. Although our new owner, Carl Pohlad, had more cash than Calvin Griffith, Carl wasn’t into pouring money into losing propositions.

So we heard a lot of questions that spring like, “Are you worried this is your last year together?” or “Do you feel pressure to produce this year to keep the nucleus intact?”

I guess in our hearts all of us knew it was put-up or shut-up time. We were a small-market club, we’d been together for a while, and it was time to win, if we were ever going to win. But honestly, other than reporters asking us about this possibly being our last year together, I never thought about it. That would be negative thinking, and like I said, my mind just doesn’t work that way.

Of course, sometimes people wonder just how my mind does work.

The Snub

One of those times came when the All-Star team was picked for 1987. We were leading the AL West by two games at the break, and when they announced the AL team, we had one player—Kirby Puckett—selected as a reserve.

I’ve always been a guy who speaks his mind, and I felt we didn’t get any respect. One pick. That’s all the Twins ever got in those years, one pick. It didn’t matter if you had two guys having great years, we just got one pick.

So I said I didn’t want to go to any more All-Star Games. And I stuck to my guns. I played in the All-Star Game as a rookie in ’82 and never went to another one. Whether me saying I didn’t want to go was the reason, I don’t know. And I really don’t care. My goal when I started playing was not to make the All-Star team. My goal was to win the World Series.

I never saw the All-Star Game as that big of a deal. When I played, it was an ego thing to go. Now it’s big money because players get bonuses for being selected to the team. I went to one, got to swing the bat once, and popped out. Big deal. It didn’t mean that much to me then, and it doesn’t mean much to me now.

Sure, it’d be nice to be considered an All-Star if you were picked by your peers. But as long as the fans are picking, it’s off-the-wall. The guys who get picked are the big names who always get picked, or the guys who play in the big cities.

The File Caper

The amazing thing about winning the division in ’87 was that we did it with just two quality starting pitchers: Bert Blyleven and Frank Viola. We spent most of the year trying to piece together a starting rotation and had 12 different pitchers start games. Les Straker emerged as our No. 3 starter, although he had only an 8–10 record and 4.37 ERA.

Our front office tried just about everything to fill out the rotation, including mid-season trades that brought us veterans Joe Niekro and future Hall of Famer Steve Carlton. They were a bit past their prime, combining for a 5–14 record and a 6.39 ERA. But Joe gave us one of the seasons most memorable moments during an August 3 start at California.

Most people remember the video clip: the ump, Steve Palermo, went to the mound to check out possible scuffing of the ball, and as Joe pulled out his back pocket, a file flew out. Joe ended up getting tossed out of the game and suspended for scuffing the ball.

Joe did scuff the ball, but not with a file. In fact, I could never figure out why Joe got kicked out for having a file in his pocket. Does anyone really think he pulled a file out on the mound and started sanding the ball? Of course not. But the real story never came out. Joe was scuffing the ball, but it was with a little piece of sandpaper that he had superglued to the bottom of his palm on his glove hand. No one ever knew it was there. When an ump looked at Joes hands, he’d hold the top of his hands up, then quick flip them over and back. You could never see the little flesh-colored piece of sandpaper on his palm.

I actually knew something was up the whole game because every time I’d catch the ball for the final out of an inning, the ump would ask for the ball. They usually don’t do that and instead let you just roll it back to the mound. Well, one inning when I got back to the dugout, the first base ump was walking down the line and showed the home plate ump the ball. I went over to tell Joe, who was sitting in the runway sharpening his nails with the file. He did that between almost every inning to give him a better grip on the knuckleball that was his bread-and-butter pitch. I told him to be careful, and his response was like, “Oh, sure. OK.” He wasn’t going to listen to me, a kid who’d been in the league for about five years.

Joe ended up having some fun with it, going on the David Letterman Show wearing a belt sander. Joe was really a neat guy, and it was a shame when he died unexpectedly in 2006. To me, Joe and Steve Carlton were like grandfathers on the team. I went out for dinner with the two of them one night in Detroit, and the chance to listen to their stories and talk baseball was something I’ll never forget.

Puck’s Big Weekend

The season itself was a roller-coaster. We had a great home record, but for some reason, we couldn’t seem to win on the road. We had a five-game lead over Oakland in mid-August. Then we went on the road and lost six straight at Detroit and Boston. On the night of August 28, we’d lost nine of 10 games and were in a virtual tie with the A’s for first place (66–62 for Oakland, 67–63 for us).

The next two games at Milwaukee belonged to Kirby Puckett. We beat the Brewers 12–3 and then 10–6. Puck was 10-for-11 with seven runs scored and six RBIs. He was 6-for-6 in the second game.

By the time we left Milwaukee, we had a one-game lead that we never relinquished. A lot of people point to Puck’s weekend as the key point of the season. It was certainly one of the key points and one of the greatest hitting weekends I’ve seen. But I have a hard time pointing to any one thing as a key in ’87 because that was a team with an incredible amount of unsung heroes.

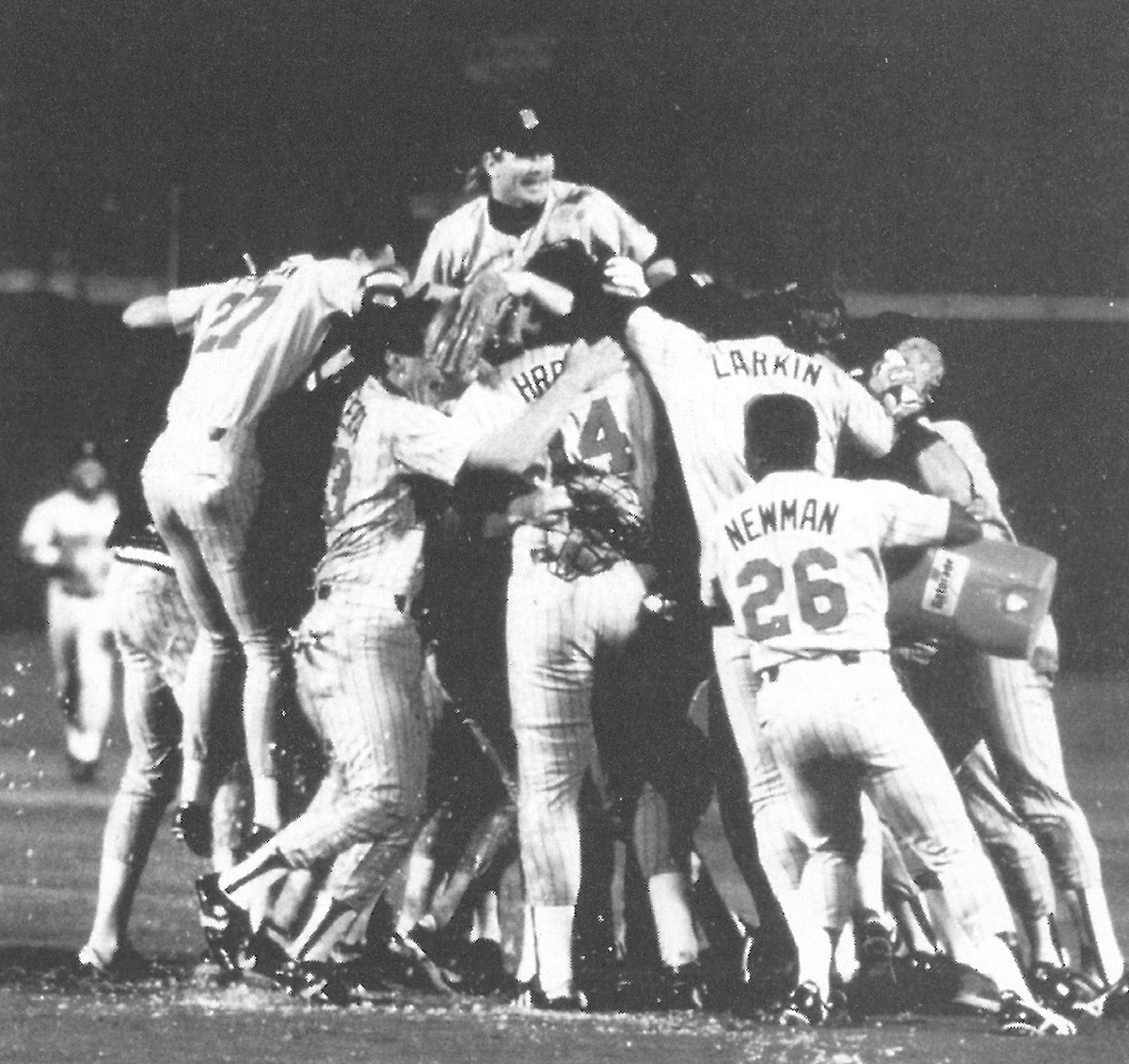

We went crazy when we clinched the AL West Division title in Texas in 1987. Courtesy of the Minnesota Twins

Our middle infield combination of Steve Lombardozzi and Greg Gagne never received much credit, but they were as important as anybody. This will surprise some people, but to me, Lombo was the best second baseman I ever played with. He was better defensively than Chuck Knoblauch, I think. Gags was a better shortstop than a lot of people think, but he never got any recognition.

Well, I shouldn’t say that. Gags got attention every time our training staff would do the body fat tests. I used to say that Gags had this chicken skin. You could take his skin and just pull it out until you could hardly believe how far it came. He used to measure about four. I always had the highest, about 19. No one told me the low score won. But that was always Gags, with that chicken skin, the thick eastern accent, and the smile with those big old teeth of his.

There wasn’t a better player than Puck on the team, and that weekend was unforgettable, but that weekend didn’t win us the division. It’s almost fitting that Lombo broke a 3–3 tie with an eighth-inning single the night we clinched the division with a 5–3 win at Texas. Lombo had a ton of big hits down the stretch.

We won it as a team of 25 guys. Twenty-five guys who loved to burn shoelaces and put shaving cream in telephones. That’s what made us what we were in 1987.