R. Jamil Jonna

CHART 1 PERCENTAGE OF QUARTERS WITH 6 PERCENT OR GREATER REAL GDP GROWTH, 1930–2015

Chart 1 is an update of work originally presented by Fred Magdoff and John Bellamy Foster (2014, 12), who provide a detailed discussion of its significance in the post–Second World War economy of the United States. The bars represent the number of quarters with at least 6 percent real GDP growth divided by the total number of quarters for a given period. Thus the denominator is 40 for each ten-year period, with the exception of 1947–1959 (51 quarters) and 2010–2015q1 (21 quarters). Data for the period covering the Second World War (1940–1946) is considered to be anomalous by economists and is therefore excluded.

Sources: National Bureau of Economic Research. Gross National Product in Constant Dollars for United States [Q0896AUSQ240SNBR]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/Q0896AUSQ240SNBR/; US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Real Gross Domestic Product [A191RL1Q225SBEA]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/A191RL1Q225SBEA/ (accessed May 7, 2015).

CHART 2 NET PRIVATE NON-RESIDENTIAL FIXED INVESTMENT AS A PERCENT OF GDP, 1949–2013

Chart 2 was originally conceived by John Bellamy Foster and Fred Magdoff (2009, 103) and is simply updated here with minor modifications. The line represents a ten-year moving average of changes in the percentage of net private non-residential fixed investment.

Sources: US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), “Table 1.1.5. Gross Domestic Product,” http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTableHtml.cfm?reqid=9&step=3&isuri=1&903=5; and “Table 5.2.5. Gross and Net Domestic Investment by Major Type,” http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTableHtml.cfm?reqid=9&step=3&isuri=1&903=139 (accessed February 1, 2015).

CHART 3 CASH AND SHORT-TERM INVESTMENTS OF THE TOP 1,200 NON-FINANCIAL US FIRMS, 1970–2013

All firms in this sample were ranked by the total revenue (REVT variable). Financial firms were excluded by creating a custom three-digit NAICS code variable and dropping the following sectors: 521, 522, and 523.

Sources: Compustat North America, Fundamentals Annual (Standard and Poor 2015); BEA, “Table 1.1.5. Gross Domestic Product,” http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTableHtml.cfm?reqid=9&step=3&isuri=1&903=5 (accessed February 1, 2015).

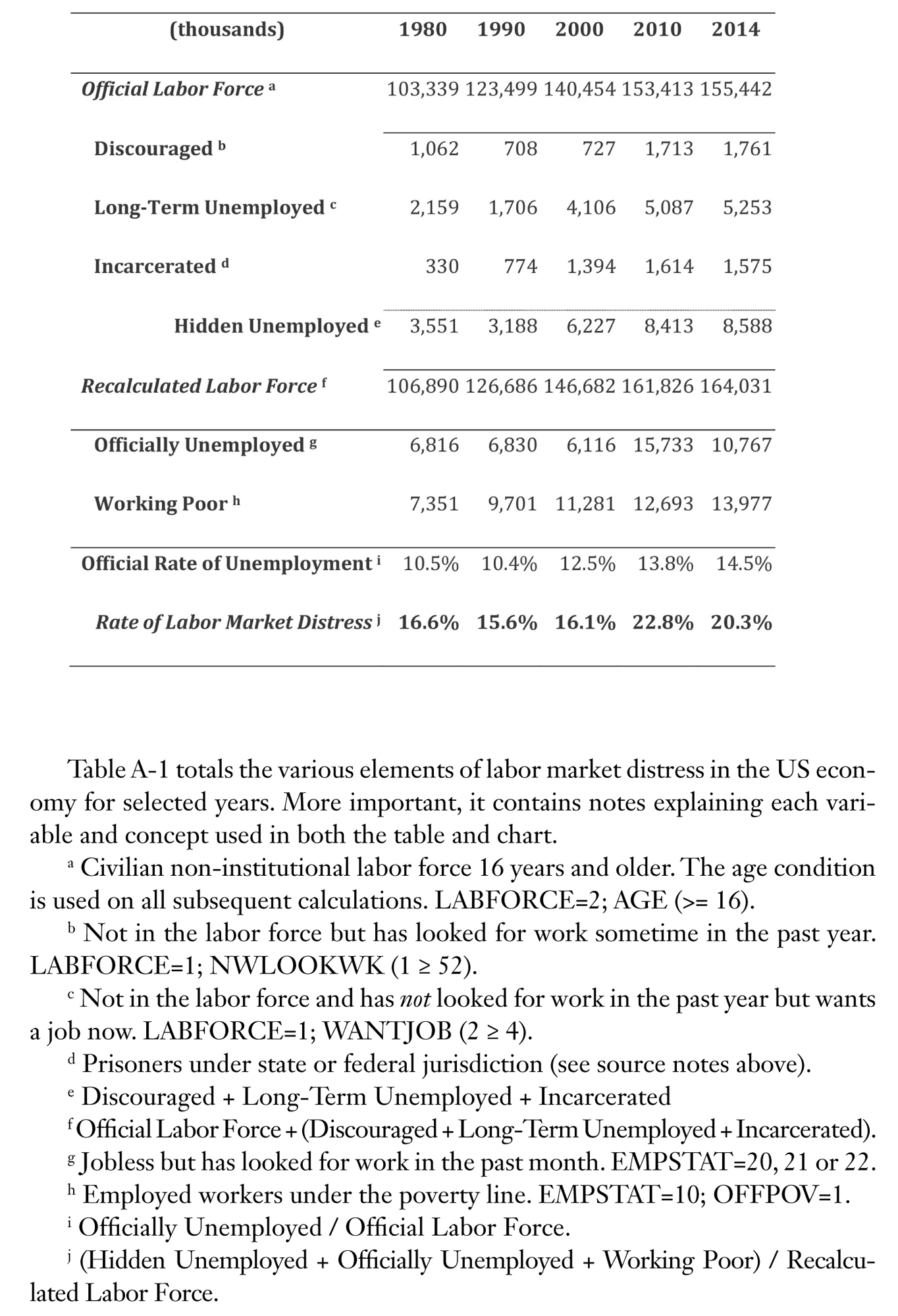

CHART 4 OFFICIAL AND HIDDEN UNEMPLOYMENT, 1962–2014

Chart 4 is a modified and updated version of data presented in my dissertation (Jonna 2012, 63–70). Hidden unemployment is defined as the sum of “Discouraged,” “Long-Term Unemployed,” and “Incarcerated.” Prior to 1976 it is not possible to determine the precise number of Discouraged and Long-Term Unemployed persons. To get a rough estimate of this part of hidden unemployment for 1962–1975, data is taken from the “Work Experience of the Population” series collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) (a part of the Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey). For these years, the number of persons unemployed for at least twenty-seven weeks is taken as a proxy for Discouraged + Long-Term Unemployed in later years. While the two sets of data are clearly not directly comparable, the values, though systematically lower (and thus more conservative), correspond closely to data for the years immediately following 1975.

Sources: Incarcerated: 1948–1977: “No. HS-24. Federal and State Prisoners by Jurisdiction and Sex: 1925 to 2001,” US Census Bureau; 1978–2013: “Prisoners Under State or Federal Jurisdiction, 1977–2004” (December 6, 2005); E. Ann Carson, “Prisoners in 2013” (September 16, 2014). (The most recent data was used whenever possible.) 2014: Estimated based on the percentage change of the previous two years. Hidden unemployed for 1962–1975: BLS, “Work Experience of the Population” (various releases). Additional historical data was obtained from the BLS by request. All other figures were tabulated using CPS microdata retrieved from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), CPS (see King et al. 2010).

TABLE A-1 Layers of the Labor Market Distress in the US Economy

CHART 5 DURATION OF JOB LOSSES IN SELECTED RECESSIONS

Chart 5 is an updated version of data presented by Fred Magdoff (2011, 27). For each recession, the level of employment is fixed and used as a benchmark to assess how long it takes for employment to reach pre-recession levels. The intent is to show that when employment, rather than economic growth, is used as an indicator of recovery a very different picture emerges.

Sources: BLS, All Employees: Total nonfarm [PAYEMS], https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/PAYEMS/; and NBER based Recession Indicators for the United States from the Period following the Peak through the Trough [USRECD], https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/USRECD/. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, January 2015.

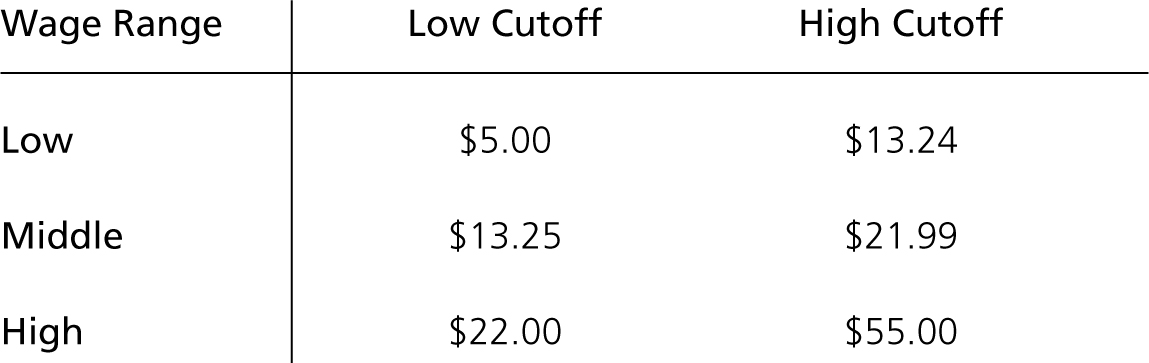

CHART 6 CHANGES IN JOB GROWTH BY MEDIAN WAGE FOR SELECTED PERIODS, 2000–2014

The calculations in Chart 6 use Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata compiled by IPUMS (see King et al. 2010). The two main variables used were HOURWAGE and OCC. Wages were converted to constant 1999 dollars using the IPUMS variable CPI99, and then to 2013 dollars using inflation factors from Sahr (2015). The wage ranges given in National Employment Law Project (2011) were used as a rough guide.

TABLE A-2 Wage Ranges Used for Median Wage Calculations

Table A-2 presents the wage ranges (in 2013 dollars) used for calculations in Chart 6. The OCC variable used in the above calculations reports occupations according to the scheme of the given year. It is important to note that the Census Bureau made significant changes to the occupational categories in 2011. As a result occupations are not directly comparable with previous years (in terms of the number of workers). For example, the occupation “Registered Nurses” was split into four distinct categories: “Registered nurses,” “Nurse anesthetists,” “Nurse midwives,” and “Nurse practitioners.” These new occupations were also augmented due to changes in the classification of other occupations. Despite these changes, the calculations above do not depend on any specific definition of a given occupational category because the occupations were categorized by median wage for each year independently. Moreover, changes to the occupational coding did not have a significant effect on the total number of workers in the largest occupational groupings.

CHART 7 INDEX OF REAL MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND REAL GDP, 1967–2013 (1967 = 100)

For Chart 7, Median Household Income data was in constant 2013 dollars and Gross Domestic Product data was in constant 2009 dollars before indexing. The index year is 1967.

Sources: “Table H-5. Race and Hispanic Origin of Householder—Households by Median and Mean Income: 1967 to 2013,” US Census Bureau, Historical Income Tables: Households; US Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Table 1.1.6. Real Gross Domestic Product, Chained Dollars,” http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTableHtml.cfm?reqid=9&step=3&isuri=1&903=6 (accessed February 1, 2015).

CHART 8 MEDIAN WAGE AND SALARY INCOME OF PERSONS 18–24 YEARS OLD, WITHOUT COLLEGE EXPERIENCE, 1964–2014

Chart 8 uses CPS microdata (King et al. 2010) to estimate the wage and salary income of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds who have not attended college. The age and “Educational attainment recode” variables (EDUC<80) were used to estimate median wage and salary income in 2013 dollars (inflation factors taken from Sahr 2015).

CHART 9 LABOR FORCE PARTICIPATION RATE, MALES,1948–2014, AND CHART 10 LABOR FORCE PARTICIPATION RATE, FEMALES, 1990–2014

The participation rates reported in Charts 9 and 10 were computed using the following series from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics: Chart 9, “(Unadj) Labor Force Participation Rate—Men” (LNU01300001); Chart 10, “(Unadj) Labor Force Participation Rate—Women” (LNU01300002).

CHART 11 ESTIMATED NUMBER OF MISSING JOBS SINCE 2000 PEAK IN LABOR FORCE PARTICIPATION, 2001–2015

John Bellamy Foster (with help from Fred Magdoff) devised the method of estimating missing jobs used in Chart 11. Foster explains that “missing jobs” represent the “cumulative number of additional jobs needed to maintain employment at the same percent of the civilian noninstitutional population as in 2000” (Monthly Review Editors 2004, 7). The calculation is carried out in two steps: (1) the potential or estimated employment level is determined by multiplying the 2000 peak rate (2000P)—64.4 percent—by the civilian noninstitutional population (CNP) for each subsequent year, thus taking into account demographic and population changes; (2) the number of missing jobs is then determined by subtracting the actual level of employment (EMP) for each year from the estimated employment level arrived at in the first step. The following formula summarizes the calculation: CNP * 2000P – EMP. The civilian population and employment in 2015 are estimated by averaging January, February and March figures. Annual figures represent the average for the given year.

Sources: “Civilian Noninstitutional Population, 16 years and over” (LNU00000000); “(Unadj) Employment Level, 16 years and over” (LNS12000000); “(Unadj) Labor Force Participation Rate” (LNU01300000); and “(Unadj) Civilian Labor Force Level” (LNU01000000), BLS, http://data.bls.gov.

CHART 12 WORKING POOR, HIDDEN UNEMPLOYED, AND OFFICIALLY UNEMPLOYED, 1968–2014

See Chart 4 for sources and discussion, and particularly Table A-1 as it includes definitions of the Hidden Unemployed and Working Poor (the latter simply defined as employed persons at or below the official poverty line). Data on the poverty status variable does not start until 1967 in the CPS dataset so there is no data for the number of working poor prior to that year. Like Chart 4, Chart 12 is derived primarily from my dissertation (Jonna 2012, 63–70).

CHART 13 UNION MEMBERSHIP AS A PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL EMPLOYED WORKERS, 1944–2014

Although union membership data prior to 1974 is not directly comparable to later years due to a change in estimation methods (from financial to survey data), the older method was relatively comprehensive and most likely under-reports union membership. This means the figures presented in Chart 13 are conservative given the overall trend. In current BLS estimates (available at the BLS site starting in 1984) there is a distinction between “Total Wage and Salary” and “Private Wage and Salary.” These distinctions do not exist for earlier years (1944–1974), which makes it impossible to distinguish public from private sector membership.

Sources: Union Members: 1944–1974: “Union membership: 1880–1999” (see Rosenbloom 2006). Prior to 1974, figures are taken from table column Ba4783 (BLS, “Union members”); for 1974, figures are taken from table column Ba4787 (CPS, “Union members among wage and salary workers”). Union Members: 1983–2014: BLS. “Total wage and salary workers, Members of unions” (Series LUU0203161800) and “Private wage and salary workers, Members of unions” (Series LUU0203182000). Total Workers: BLS. “(Unadj) Employment Level, 16 years and over” (Series LNS12000000). http://data.bls.gov. Retrieved March 2015.

CHART 14 NUMBER OF WORK STOPPAGES IDLING 1,000 WORKERS, 1947–2014

The faint line in Chart 14 is actual data while the darker line represents a ten-year moving average.

Source: BLS, “Number of Work Stoppages Idling 1,000 Workers or More” (Series: WSU100), http://data.bls.gov.

CHART 15 AVERAGE CHANGE IN INCOME SHARE FOR SELECTED INCOME GROUPS, 1935–2014

Chart 15 is designed to highlight how significant the differences in income share movements are for the top income earners as opposed to those at the bottom. By averaging annual changes in income share over ten-year periods it is possible to assess simultaneously the trend and relative movements in income share for these groups.

Source: Piketty and Saez (2007). Series updated by the same authors in “The World Top Incomes Database,” http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu.

CHART 16 UNEMPLOYED FOR AT LEAST 15 WEEKS AS A PERCENTAGE OF THE LABOR FORCE, 1962–2014

Chart 16 uses CPS microdata compiled by IPUMS (see King et al. 2010). The series is constructed using the interval variable DURUNEM2 (≥9), which only includes respondents who have looked for work in the last four weeks. This means that “Discouraged” and “Long-Term Unemployed” workers are excluded. The faint line represents actual data and the darker line the five-year moving average.

CHART 17-ADDENDUM Revenue of Top 100 Non-Financial US Firms (by Revenue) as a Percentage of US GDP, 1950–2013

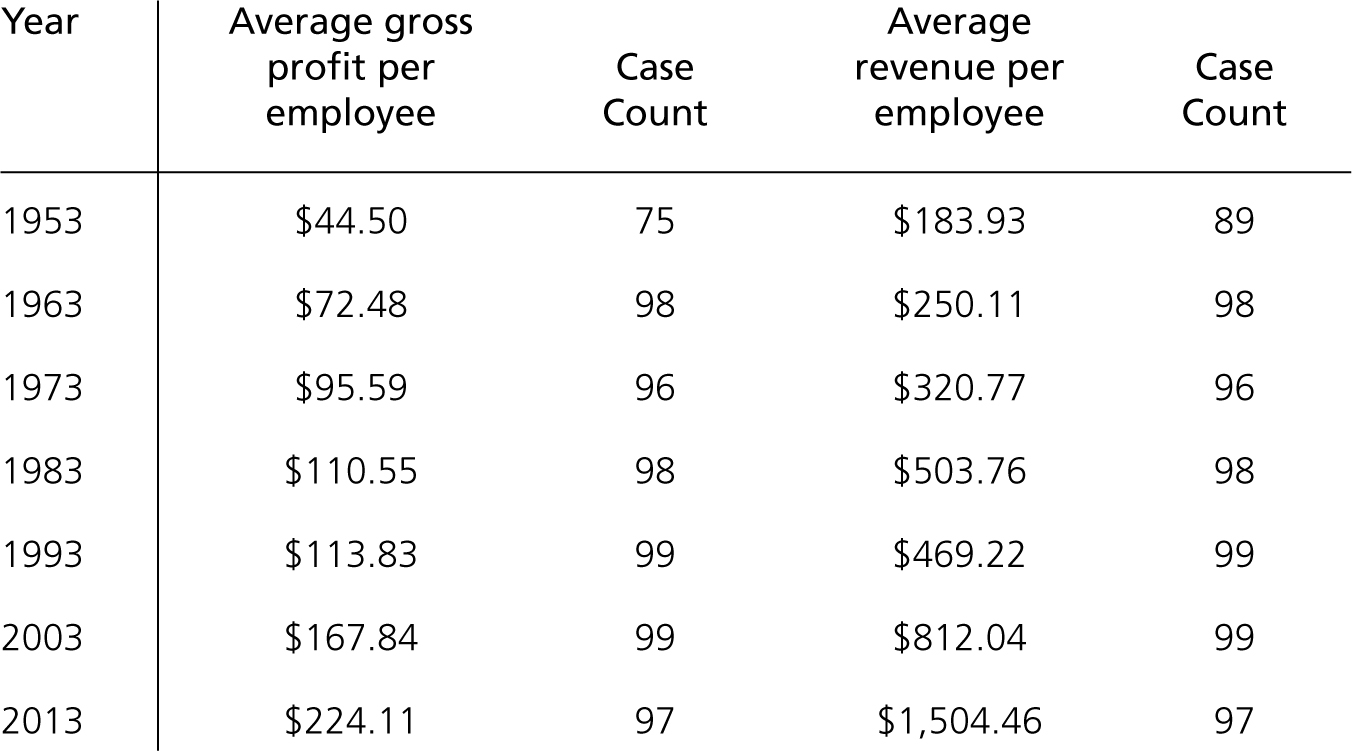

CHART 17 US REVENUE AND US GROSS PROFIT PER EMPLOYEE OF THE TOP 100 US FIRMS, 1953–2013

In Chart 17 and Chart 17-addendum, firms are ranked by total revenue (REVT variable) for the given fiscal year. If either gross profit (GP variable) or Employment (EMP variable) data were not available for a given year the case was dropped. Actual figures along with case counts and conversion factors for Chart 17 are shown in Table A-3. For Chart 17 the average number of cases for the 1950–2013 period was 97.

Sources: Compustat North America, Fundamentals Annual (Standard & Poor 2015); and US Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Table 1.1.2. Contributions to Percent Change in Real Gross Domestic Product,” http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTableHtml.cfm?reqid=9&step=3&isuri=1&903=2. Accessed February 2015.

It is important to note that the data presented in Chart 17 on average revenue per employee does not distinguish between foreign and domestic workers. The number of foreign workers employed by the largest US multinational corporations has grown considerably. According to data provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), about 50 percent of the workforce of the top nonfinancial firms incorporated in the United States were foreign in 1990 (26 firms); by 2013 it was 60 percent (23 firms). Moreover, the revenue per worker for foreign workers is typically about 20 percent higher than for domestic workers (see UNCTAD 2014 and earlier reports).

TABLE A-3 Gross Profit and Revenue per Employee with Case Counts (thousands of 2013 dollars)

CHART 18 NUMBER OF NEW YORK TIMES STORIES MENTIONING AUTOMATION (THOUGH FEBRUARY 2015)

Research conducted by Grace Hebert, using New York Times index.

CHART 19. THEORETICAL GROWTH IN COMPUTING POWER

In computing, “FLOPS” is an acronym for FLoating-point Operations Per Second, and the preceding “G” stands for giga (or 109). Thus a GFLOP is a billion floating-point operations per second. The measure “GFLOPS per dollar” is used in accordance with the “Law of Accelerating Returns” developed by Kurzweil (2012: 343–344). The series starts in 1984, when the Cray X-MP/48 supercomputer maxed out at around 0.4 GFLOPS at a cost of approximately $27 million (2014 dollars), meaning the cost per GFLOP was about $85 million. From this point, the series simply doubles each period, assuming an exponential increase in calculations per second per dollar every thirteen months.

SOURCES AND NOTES FOR VOTING FIGURES IN CHAPTER 3

“Total votes” for the majority party is the sum of votes received by that party in the general election of a given year, for either the House or the Senate. For the Senate, the “voting-age population” is the sum of the population eighteen years old and over of the states that had a senatorial race in a given election year. For the House, the “voting-age population” is simply the total population eighteen years old and over in a given election year. Voting-age population figures for 2014 were estimated using the percent change figures (2013 to 2014) reported by the US Census Bureau.

Sources: Voting figures: 1998–2012: “Votes Cast for the U.S. House of Representatives by Party” and “Votes Cast for the U.S. Senate by Party,” Election Results. Public Records Office: Federal Election Committee; 2014: “Statistics of the Congressional Election from Official Sources for the Election of November 4, 2014,” Office of the Clerk, US House of Representatives, Karen L. Haas, pp. 53–54, published March 9, 2015, http://clerk.house.gov/member_info/election.aspx. Population figures: 1998–2012: “Population Estimates for the U.S. and States by Single Year of Age and Sex”; 2014: “National, State, and Puerto Rico Commonwealth Totals Datasets: Population change and rankings: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014,” US Census Bureau.

REFERENCES

Foster, John Bellamy, and Fred Magdoff. 2009. The Great Financial Crisis: Causes and Consequences. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Jonna, R. Jamil. 2012. “Toward a Political-Economic Sociology of Unemployment: Renewing the Classical Reserve Army Perspective.” Edited by John Bellamy Foster. Doctoral Thesis. John Bellamy Foster, Chair. Eugene: Department of Sociology, University of Oregon. doi:10.1080/08854300.2012.686280.

King, Miriam, Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Sarah Flood, Katie Genadek, Matthew B. Schroeder, Brandon Trampe, and Rebecca Vick. 2010. “Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 3.0.” Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. http://cps.ipums.org/cps.

Kurzweil, Ray. 2012. “On Modis’ ‘Why the Singularity Cannot Happen.’” In Singularity Hypotheses, edited by Amnon H. Eden, James H. Moor, Johnny H. Søraker, and Eric Steinhart, 343–348. Berlin: Springer.

Magdoff, Fred. 2011. “The Jobs Disaster in the United States.” Monthly Review 63 (2): 24–37. doi:10.14452/MR-063–02–2011–06_2.

Magdoff, Fred, and John Bellamy Foster. 2014. “Stagnation and Financialization: The Nature of the Contradiction.” Monthly Review 66 (1): 1–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.14452/MR-066–01–2014–05_1.

Monthly Review Editors. 2004. “The Stagnation of Employment.” Monthly Review 55 (11): 3–17.

National Employment Law Project. 2011. The Good Jobs Deficit. New York, NY. http://www.nelp.org/index.php/content/content_publications/?issue=labor_market_research&type=reports_and_resources.

Piketty, Thomas, and Emmanuel Saez. 2007. “Income and Wage Inequality in the United States 1913–2002.” In Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century, edited by Anthony B. Atkinson and Thomas Piketty, 141–225. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rosenbloom, Joshua L. 2006. “Union Membership: 1880–1999 (Series Ba4783–4791).” In Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition Online, edited by Susan B. Carter, Scott Sigmund Gartner, Michael R. Haines, Alan L. Olmstead, Richard Sutch, and Gavin Wright. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ISBN-9780511132971.Ba4783–4998.

Sahr, Robert. 2015. “Inflation Conversion Factors for Years 1774 to Estimated 2025, in Dollars of Recent Years.” Oregon State University. http://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/spp/polisci/research/inflation-conversion-factors-convert-dollars-1774-estimated-2024-dollars-recent-year.

Standard and Poor. 2015. “Compustat North America, Fundamentals Annual.” Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS). http://wrds-web.wharton.upenn.edu/wrds/ds/comp/index.cfm.

UNCTAD. 2014. World Investment Report 2014. New York: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. http://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=937.