ETHNICITY AND CREOLIZATION

When Europeans arrived in the South, they entered a region that had been inhabited for perhaps 13,000 years and was, by the 16th century, well peopled by a diversity of protostates and chiefdoms. Africans joined the people of the South in 1619. Their status as slaves or indentured servants on arrival remains ambiguous. Accounts of southern history and experience onward from that time have conventionally, and simplistically, discussed the region’s ethnic mix in terms of three broad categories relating to the three continents of colonial southerners’ origins. Further obscured by late 19th- and 20th-century binary racial categorization of institutions and worldviews, the diverse ancestral origins of early southerners have only recently become a subject for recovery among scholars and in popular culture.

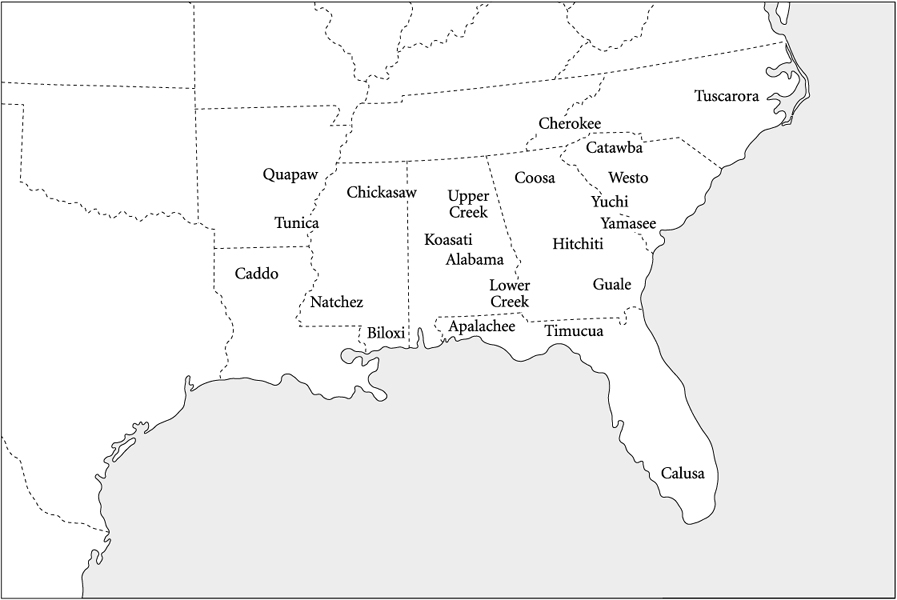

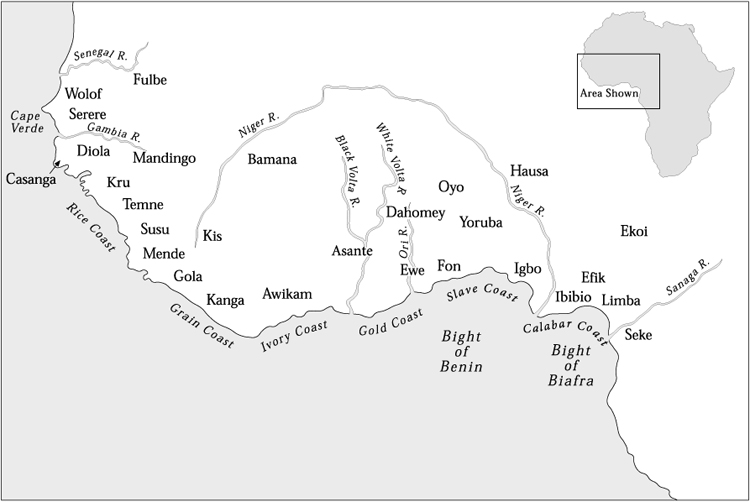

A social, political, and scholarly focus on racial categorization has denied the cultural (ethnic) differences within what have been called “racial” groups. The American Indians inhabiting the South at the beginning of the historic period included speakers of at least five major language families, within which there were long-standing ethnic divides that caused some to ally with outsider Europeans against other Native Americans. While the majority of the first European southerners came from England, Scotland, and Ireland, they did not share a culture or worldview, and some Catholic Irish and Highland Scots spoke their own versions of Gaelic rather than English. German, Swiss, French, and Spanish settlers early added to the religious, linguistic, and social mix of the new colonies. Africans came predominantly from the nations between Angola and Ghana (the Gold Coast), but also from the Gambia (Senegambia), Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Igbo country. Just as European colonists maintained their distinct identities from their particular nations (or regions of their home nations), Africans continued to think of themselves as Yoruba, Mandingo, Fon, or Wolof for several generations. Some ethnic groups were less likely to socialize or partner with members of others. Religious beliefs, song, folklore, and artistic traditions also perpetuated national and cultural affiliations within slavery on ethnically heterogeneous plantations.

Recent scholarship has begun to uncover the ethnic diversity of the early South as well as to document the contemporary arrival of new cultural groups in the region. This volume reflects both trends. Eliding the metonyms and stereotypes of the South in strictly black and white, this collection of essays attempts to represent the panoply of ethnicities that combined to shape the region. As culturally constructed notions, racial identities are imposed generally by those with whom one does not share a designation. Ethnic identity one traditionally learns at a grandparent’s knee. Ethnicity lies in folktales, in tying fishing nets, in conceptions of the supernatural, in the music that delights multiple generations simultaneously, in the foods that mean home. Ethnic identities are cultural identities, and as such they are dynamic and renegotiated in different contexts and periods. Some consider southern identity, shared by black and white southerners (as opposed to “southern blacks and whites”), an ethnic identity within the United States. Since the 1700s the notion of the region as distinct has endured, although what is southern in any given period continues to evolve. Southern culture, or the multiple southern cultures of the South’s many subregions, is a complex amalgamation of disparate ethnicities and traditions from around the globe. After centuries of blending, the sum is undoubtedly greater than its parts but is hardly a finished product.

Ethnicity. The concept of ethnicity comes from the Greek ethnos, meaning “people” or “nation.” Herodotus flexibly described the Dorians, Kolophonians, Ephesians, and Ionians as ethne according to what festivals they celebrated, their language or dialect, their mythic genealogies tracing group origins to an eponymous ancestor, and sometimes their area of residence. Anthropologists today define ethnic groups similarly as having shared customs, linguistic traditions, religious practices, and geographical origins. Members of an ethnic group might also exhibit specific gender roles and inheritance patterns. Frederick Barth’s groundbreaking work Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Difference (1969) led anthropologists to describe “ethnic boundary markers” (the possession of a distinctive language or dialect, a particular style of dress, music, and cuisine, and religious expression), although no one of these alone defines an ethnic group.

Membership in an ethnic group often relates to kinship and descent, but even when a belief in shared ancestry is involved in ethnic identity formation, it can be what anthropologists call “fictive kinship” and is often mythic. When ethnic identities are oriented to the past, those who claim them may have an emotional investment in legend and renegotiate history in more appealing forms as heritage. Ethnic identities evolve over time and are often quite voluntary. Those claiming an ethnic identity form an ethnic group in contrast to “ethnic categories,” which are identities imposed from the outside (generally on a minority group). Occasionally an ethnic category goes through “ethno-genesis” and becomes an ethnic group—as with labels like “Hispanic.”

Ethnic celebrations, heritage tourism to ancestral homelands, and an interest in ethnic music, foodways, and material culture have become an increasingly accepted part of American life. Spurred by America’s bicentennial celebrations and popular books such as Alex Haley’s Roots (1976), genealogy is now one of the fastest-growing hobbies in America. Even those whose families have been in the South for over 300 years are looking for origins and reclaiming what they perceive as ancestral traditions from nations where they would never be considered anything other than American.

While many people may reject a familial ethnicity, others actively embrace one their parents, grandparents, or more distant ancestors relinquished. How one values or emphasizes ethnicity may relate to the prestige (or lack thereof) that such an identity carries and to context (a religious holiday rather than an average worship service, within the home rather than the office). An individual may have more than one ethnicity simultaneously and play on overlapping sets of loyalties depending on the situation. The situational selection of ethnic identity can be different from “symbolic” or “convenience” ethnicity (embracing an ethnic identity self-consciously at festival occasions without living an ethnic existence daily). One may emphasize one’s Mexican ancestry on Mexican Independence Day, and also acknowledge the Scottish branch of one’s family by learning a song in Gaelic or competing in Scottish athletics, but otherwise live a nonethnic life. One might even dress for heritage events and festivals to signify a personal creole combining a sombrero and a kilt. Affiliating with an ethnic group voluntarily may involve acquiring ethnic shibboleths or rediscovering those devalued or discarded by one’s ancestors.

Some scholars dismiss symbolic ethnicity as nostalgic yearning for a long-lost tradition and identity and as a superficial aspect of personal identity. However, such a perspective denies the deep emotional investment people make in voluntary or reclaimed identities. While individuals may not materially display their ethnicity to outsiders on a regular basis, scholars cannot simply assume it is not incorporated as part of their worldview or that it is detached, or even tangential, to their daily, nonfestival realities. Descendants of many of the groups in this volume may no longer be commonly identified as ethnic, but their origins and traditions (or invented traditions to commemorate those origins) may be quite significant in their family life and formative of a personal identity.

Many of the essays in this volume include information from the U.S. Census Bureau. In 1980 the census first included an “ancestry question” to collect selective information on ethnic origins and identity. In 1990 and 2000 the question simply read, “What is the person’s ancestry or ethnic origin?” According to the Census Bureau, “ancestry” refers to a person’s ethnic origins or descent, roots, heritage, or place of birth (although place of birth and ancestry are not always the same). The ancestry question does not measure to what extent a person is aware of ancestral origins. For example, a person reporting “German” on the census might be actively involved in the German American community or might only vaguely remember that ancestors centuries removed came from Germany. State-by-state census data is more useful than regional summaries in ascertaining which ethnic identities southerners claim, as the Census Bureau includes Oklahoma, West Virginia, Washington, D.C., Delaware, and Maryland within the southern region. Maryland was once culturally southern, and portions of Oklahoma and West Virginia still claim to be, but this inclusive mapping varies from both scholarly and popular specifications of the region.

Census data on ethnicity can be misleading, not only because numbers are based on a sample of the population, but also because ethnic identities and notions of “race” are conflated. Race categories on the census include both color designations and national origin groups. For example, Koreans are not listed on state ancestry charts because the census includes “Korean” as a choice under the “race” question. Tabulated numbers may often appear contradictory when, for example, more people specify “African American” in answering the census’s race question than those answering the ancestry question who may then report nothing or a different, more specific identity (Nigerian, Haitian, Sudanese). To find figures for Mexicans and Spaniards, Panamanians or Guatemalans, for example, one must look to special Census Bureau national reports rather than state-by-state ancestry charts in which Central and South American nationalities are oddly not listed. The Census Bureau now couples a question on ethnicity (“Is this person Spanish/Hispanic/Latino?”) with its question on race. The rationale as to why the bureau excludes specific Latino ethnicities from ancestry data—but collects information on Norwegians, Subsaharan Africans, Slovaks, and West Indians as ethnic groups—is not obvious, nor have such categorizations remained constant. Government definitions change with the evolving political and social implications of identities.

In the media and on government forms, ethnicity is incorrectly used interchangeably with “race,” although ethnicity does not mean race. Ethnicity refers to cultural and social aspects of identity, not biological aspects or phenotype (physical appearance), which is the most common meaning of “race” in the United States. In the 19th and even early 20th centuries, “race” often denoted national or regional origins or referenced a particular cultural group, commonly in connection with the spurious notion that there could be any biological predisposition to cultural distinctiveness. Based on cultural assumptions about physical appearance, “race” is socially constructed rather than biologically valid. As a species, we are too evolutionarily recent to have discrete “racial” populations. The human genome carries only superficial markers relating to aspects of appearance such as hair form and melanin production for skin and eye color (characteristics that often relate to long-term environmental adaptation); it does not distinguish separate subspecies like “breeds.” The continuum of human physical variation does not fall into three, five, nine, or more discrete groups, as scholars such as Johann Herder (1744–1803) and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840) proposed in the drive for Linnaean classification, and as popular culture continues to do in order to define difference for social and political expediency. Social classifications of “race” focus predominantly on phenotype and have done so since the Ancient Egyptians divided the world’s people into “red” for Egyptian, “yellow” for people to the East, “white” for those to the north, and “black” for Africans from the south. However, since the writings of the ancient Greeks, “ethnicity” has properly referred to identity and culture.

The 20th-century conflation of “race” with ethnicity has led to the post–civil rights era racialization of distinct cultural groupings. The relatively recent category of “Asian Americans” provides a higher national profile for about 24 ethnic groups on the U.S. Census and on the American political scene. However, such a designation not only bundles East Asian groups such as Korean, Japanese, Malaysians, Vietnamese, and Chinese Americans into a shared grouping, it also absorbs Nepalese, Indian, and Pakistani Americans within one “racial” category despite their completely separate origins, histories, and cultural traditions.

While sociologist Max Weber had used the concept in work published in 1922 and other scholars had explored the notion in the 1940s, “ethnicity” did not enter public discourse and dictionary usage until the early 1960s. Today, the word is ubiquitous. Perhaps in reaction to globalization, scholars of many disciplines use “ethnic” or “ethnicity” when they might have employed “cultural” or “subculture” a quarter of a century ago. Ethnicity has come to mean distinctiveness, if variously defined. Many scholars view ethnicity as a political identity in relation to class, racial, or other potential social conflicts and discuss claims to ethnic identities as negative when embraced by a privileged group, but as a positive form of “resistance” when embraced by an unprivileged one.

However, class and power differentials exist within ethnic groups as well as between them. Ethnic identities are not necessarily exclusionary. Not only may one be a member of more than one ethnic group, one also may share an ethnic identity with those whom society designates as a different “race” from oneself. Increasingly, Americans are identifying themselves as multiethnic. Irish Americans not only celebrate their Irish roots; they may also claim to be German-, Mexican-, African-, or Italian-Irish Americans. Southerners may simultaneously feel southern and Chinese, or southern and Italian, and sometimes conflate the two. This is most obvious in expressive culture and at festivals, which are superb indicators of the evolution and recombination of ethnicities.

For those perceiving ethnicity as primarily political, the failure of the melting pot assimilationist ideal was considered a problem—an “ethnic problem.” The 1960s and 1970s then witnessed a move from assimilationist models for immigrants to ideas of pluralism (a coexistence and toleration of difference). In the 1980s and 1990s, multiculturalism (a celebration of difference) replaced pluralism. Ethnicity is a much more comfortable, if not beatitudinous, concept than it was a quarter of a century ago. Americans now find ethnic food aisles in grocery stores, wear ethnic clothes, decorate their homes in “international ethnic pastiches,” and often assume that multiculturalism means nonracism as if ethnicity meant race. While ethnicity may be “optional” for many Americans, the selection of identities and their renegotiation is revealing, not only of how Americans perceive each other, but also of our particular moment in history. Similarly, the recognition and study of ethnicities in the South communicates significant insights about the region’s place historically and currently within both national and global frames.

Creolization and Creole Groups. Southern culture is a product of nearly 20 generations of creolization (a blending of cultures after long exposure, coexistence, and interaction of multiple social groups). W. J. Cash, Ralph Ellison, and historian Charles Joyner have remarked that every white southerner has an African heritage as well as a European one, and every black southerner has a European heritage as well as an African one. This idea continues to resonate because southern culture is a complex hybrid of varied traditions. Although southern society created well-bounded public hierarchies around difference, southern culture is the result of heterarchical relationships between individuals with regular and intimate interactions. Despite slavery and Jim Crow, the flow of ideas, customs, and worldviews was not solely top-down. Those with the least overt power in southern society created the infrastructure, erected the buildings, produced the cash crops that once made the South wealthy, and carried out a variety of skilled occupations essential to the smooth working of any urban settlement or rural community. Those enslaved—or, after slavery, in domestic service—cared for the children of the elite, taught them manners, and shaped their speech and tastes. Such formative relationships, and more subtle, ongoing exchanges, produced the cultural creoles we conceive of as southern traditions.

What we think of as typically “southern” is a product of centuries of cultural blending. Bluegrass is a mix of Irish and British fiddle traditions and African-derived banjo. Jimmie Rodgers, “the father of country music,” combined Swiss yodeling with black field hollers in the 1920s to create his characteristic “blue yodels,” which Chester Burnett of the Mississippi Delta blues tradition subsequently adapted to his own style and earned himself the moniker Howlin’ Wolf. Southern spirituals merged the rhythm and structure of African music with elements of British text and melodies. Southern rock groups such as the Allman Brothers Band and Lynyrd Skynyrd produced fusions of rock and roll, blues slide guitar, jazz, soul, and rhythm and blues with southern dialect. Yale ethnomusicologist Willie Ruff has recently suggested that a distinct psalm-singing style in southern African American congregations called “presenting the line” derives from “line singing” or “precenting the line” in the Scottish Highlands. He argues that Gaelic-speaking enslaved Africans learned the singing style and notes a church in Alabama where their descendants worshipped in Gaelic as late as 1918. Employing an African American performance style and traditionally sung in French, zydeco music blends the blues with Afro-Caribbean rhythms and tone arrangements from Cajun music (the European American analogue to zydeco).

Cultural exchanges with American Indians transformed both Europeans and Africans in the South, yet such creolizations are perhaps less obvious today in part because of the colonial demographic revolution. As Peter Wood has noted, in 1690 approximately 250,000 people lived in the South (80 percent Native Americans, 19 percent Europeans, and perhaps 1 percent slaves). In 1790, after a century of introduced diseases and colonial expansion, just under 5 percent of the estimated 1.7 million southerners were Native Americans, 60 percent were Europeans, and 35 percent were of African descent (a large percentage despite historians’ estimates that only 6 percent of Africans crossing the Atlantic in the 18th-century slave trade came to North America). While Europeans enslaved some Native Americans and intensive contact between enslaved American Indians and Africans took place in Charleston in the late 17th century, the Tuscarora War of 1711 and the Yamasee War four years later pointed to the dangers of a possible alliance between them. European colonists forfended this by hiring native peoples to capture escaping African slaves and by sending enslaved Africans into battle against American Indians. While such policies were common, intermarriage and cultural exchange did continue.

Mississippi Choctaws playing stickball (Photograph courtesy of Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians)

American Indians assisted initial European settlement by teaching new settlers to clear the foreign forest and grow native crops such as squash, maize, beans, and tobacco. They influenced early patterns and locations of colonial settlements in relation to their defense of their own and shaped the course of southern history through their military alliances. Newly arrived southerners borrowed indigenous architectural traditions, buckskin, and canoes in settling what they considered the frontier. Southern foodways draw from indigenous foodways; Native Americans made the first cornbread (or pone), grits, and succotash (a mix of corn kernels and beans). European Americans also adapted native crops to their own traditions (their use of maize to produce whiskey, for example). American Indians taught new southerners herbal remedies, and soft drinks like root beer and Coca-Cola had precursors in indigenous sassafras Indian tonics. Few indigenous languages remain extant in the Southeast, but many groups developed their own dialects of English (regional variants that are distinctive for their grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation). For example, in North Carolina the vernacular English of the Lumbee employs unique vocabulary words such as juvember for “slingshot” and ellick for “coffee.” Like other peripheral dialect areas with a long history of insularity, their speech also retains centuries-old English terms such as mommuck (mess) and toten(ghost). Native American linguistic contributions to southern culture include many loan words such as squash, hominy, hickory, opossum, skunk, and, of course, southern place names such as Tallahassee, Okefenokee, Santee, Mississippi, and Tullahoma.

American Indians’ presence and impact on the southern cultural landscape decreased as that of African and African American populations increased. U.S. Census figures for 1860 indicate that European and enslaved African populations were very close in number in several southern states. That year, the population of Alabama was reported to be 54 percent “white” and 45 percent “slave”; similar estimates exist for Florida (55 percent and 44 percent), Georgia (56 percent and 43 percent), and Louisiana (50 percent and 46 percent). Two states had an enslaved population substantially larger than that of European Americans: in Mississippi “slaves” constituted 55 percent of the population while “whites” composed 44 percent, and in South Carolina the ratio was 57 percent to 41 percent. The increasing recognition of African influences on southern culture include linguistic contributions. Southern dialects evidence African contributions, including loan words such as goober (related to Kongo n-guba, or “peanut”), okra (a word of Bantu origin), yam (of West African origin), tote, gumbo, and boogie. Staples of southern foodways (including rice, types of squash, black-eyed peas, and okra) came from Africa, as did a preference for certain spices.

Foodways specific to enslaved African Americans—getting by on the less desirable cuts of meat and the vegetables they could grow on small plots—developed over time into “soul food,” including chitlins, mustard greens, ham hocks, ham salad, pigs’ feet, and hoppin’ John (a dish featuring black-eyed peas, rice, and ham). Food items once considered soul food, such as barbecue, fried catfish, candied yams, hush puppies, coleslaw, and pot likker, have long been common to southern tables across ethnic divides.

Africans of many ethnic groups brought a strong reverence for ancestors, a belief in spirits, and folk-healing traditions that led to hoodoo and conjure ( ju-ju) and the southern practice of voodoo (African traditions fused with folk practices of French Colonial Catholicism and the magicomedical knowledge and pharmacopeia of American Indians). Of the “queens,” “doctors,” or “workers” of voodoo, Marie Laveau was America’s most famous, and her grave is still a site of pilgrimage in New Orleans. Africans adapted Christian beliefs to African expectations of the divine. African trickster characters and deities populate African American folktales in which the rabbit (shared with Native Americans) and the signifying monkey figure largely. Echoing earlier traditions of storytelling and performances of ritual insult, today’s Mardi Gras Indians of New Orleans sing carefully crafted songs in mock battles that involve verbal competition and boasting about the reputation of individuals and neighborhoods.

Across the Deep South, the shotgun house stands as one of the most-cited examples of African-influenced architecture. The narrow, one-story buildings have a front porch, a gabled roof, and rooms aligned in single file. John Michael Vlach has convincingly argued that the shotgun house derives from those of the indigenous Arawak Indians of Haiti and modified by Africans brought there and then, in the early 19th century, to the South. The southern front porch may also find its origins in the vernacular precolonial architecture of West Africa and the West Indies. The Georgian “I houses” of Charleston, S.C., are a part of this tradition and feature a porch running the length of one side of the house that can be closed off from the street by a formal door.

Some of the most noted cases of syncretic Africanisms in the United States are the folkways and linguistic traditions of South Carolina’s Gullah and Georgia’s Geechee peoples. While enslaved Africans retained ethnic identities for generations, their interactions with Africans of other nationalities produced cultural creoles. Eventually, a racialized identity replaced ethnicities and Africans created an African American culture. In the Chesapeake and North Carolina, slaves and European Americans interacted on a regular basis, and slave populations there became more anglicized than in the Lowcountry and Sea Islands. South Carolina planters often lived in Charleston and left overseers to run their rice plantations. Having less interaction with European Americans, slaves there retained and exchanged more of their ethnic traditions.

The Gullah and Geechee peoples of the Lowcountry and Sea Islands maintain traditions that are a syncretism of those of several different West and Central African ethnic groups (including the Mende, Limba, Temne, Fante, Fon, and others). Their language is not African but African American, being a creole of various African languages and English influences. In Gullah-speaking communities, individuals still have African “basket names” (nicknames) such as Bala, Jah, or Jilo. Names indicate the day on which a child was born (for example, Yaa for a girl born on Thursday and Yao for a boy), reference physical features, or indicate a kinship relationship (bubba would equate with “brother” in English). Hand clapping and foot stomping replaced African drums and still accompany shouts in Christian worship (Methodist and Baptist) in Gullah churches. Today, the Gullah/Geechee Sea Island Coalition encourages cultural revitalization and aims to achieve international recognition as a nation with self-determination like a Native American tribe. This goal is contested since the Gullah/Geechee are not indigenous to the Sea Islands but formed a Creole society there. Elsewhere, descendants of slaves from the Lowcountry and Sea Islands who joined a Native American tribe also find their status in question.

Perhaps as early as the late 1600s, Africans escaped plantations in what are now Gullah/Geechee communities and settled among the Florida Seminole, where they lived beyond the reach of British colonial administrators. Known as the Black Seminoles, they spoke Gullah and the Muskogee or Mikasuki languages of the Seminole, adopted many of their cultural attributes, and fought in the Seminole wars. Removed to Oklahoma with the Seminole, the Black Seminoles became known as “the Freedmen,” and their status and rights as tribal members have varied over the last century and a half. As exogamy has led people without active ties to the Seminole Nation to enroll as tribal members (for the benefits and services membership entails), the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma adopted a resolution in 2000 requiring proof of one-eighth “Seminole Indian blood” for enrollment. Such a requirement excludes the majority of Black Seminoles from tribal membership and would seem to dim the multiple-centuries relationship that yielded social and political exchanges and cultural creolization.

The term “creole” has multiple meanings. A creole replaces a pidgin, the form of communication in first contact between two or more groups speaking different languages. The francophone dialect of south Louisiana is one example. Creole also has indicated a descendant of the original French or Spanish settlers of the southern states, or a person of African or Caribbean and European ancestry who speaks a creolized language, especially French or Spanish. Creole cuisine in the South refers to a New Orleans–style tomato, onion, and pepper sauce or a dish like filé gumbo (a union of Choctaw and West African foodways). Creole cuisine and culture have long been staples of the Louisiana tourism industry, but they also inspire the devoted work of local preservation and heritage societies. Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, La., has developed the Louisiana Creole Heritage Center and has initiated a Creole Studies Consortium. Although “Creole” can apply variously to people of European or African descent, for some the term distinguishes African Americans of French-speaking Louisiana from their European American Cajun neighbors in south Louisiana. However, some people of African descent self-identify as Cajun today.

Immortalized in Longfellow’s Evangeline, Cajuns are descendants of Catholic French Acadians who settled in French Louisiana (some also went to Maine) after being expelled from Nova Scotia by the British in the mid-18th century. After centuries of mixing with other ethnic groups, Cajun surnames now include the German Hymel and Schexnider, the Spanish Castille and Romero, and the Scots-Irish McGee. Partly through interaction with southerners of African descent, Cajuns developed spicy dishes such as dirty rice, gumbo, and other foods reflecting their local resources and subsistence, such as boudin (Cajun sausage) and bouille (cane syrup pie).

Defining who is a “Creole” remains contentious. Most simply and inclusively put, the category of “Creole” may refer to anyone with African or European (but not Anglo-American) ancestry who was born in the Americas. The South has many creolized populations with ethnic identities original to the region, but it also has many populations that we would now call Creole groups that did have Anglo-American ancestry—some that were once called mulattos, triracial isolates, pardos, “mixed-bloods,” and worse.

Across America, a practice called hypodescent assigns children of mixed unions the identity of the socially and economically disadvantaged group. Categorized as “colored” by the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Statistics because her great-great-great-great-grandmother was black, Susie Phipps garnered international attention in 1982 by trying to have herself declared “white.” According to America’s “one-drop rule,” one black ancestor makes a person black, but one white ancestor does not make a person white. Following the death of over 600,000 combatants in the Civil War—the outcome of which made the abolition of slavery through the Thirteenth Amendment possible—“black codes” and then Jim Crow laws created a period of racial segregation across 29 states (the name “Jim Crow” originally applied to segregated facilities in the pre–Civil War North). In 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court approved the segregation of public facilities in Plessy v. Ferguson. In 1954 Brown v. Board of Education overturned that decision, but many “separate-but-equal” practices continued until the federal civil rights legislation of the mid-1960s. The biracial classification schemes of the New South replaced much more elaborate classification schemes from the colonial and antebellum periods.

Enslaved Africans and African Americans were sometimes freed, especially (but not always) when they were children of their mother’s master. They occupied an ambivalent position, frequently owning slaves but at risk of being captured and returned to slavery themselves if they traveled or moved out of areas in which they were known. By 1800 the majority of free people of color in America lived in the South (60,000). By the time of the Civil War, their numbers had grown nationwide to 488,000, with the majority (262,000) still living in the southern region. In the 19th century, free persons of color (gens de couleur libre) living along the Gulf Coast began calling themselves “Creoles of Color.” They maintained their identity and communities through the Jim Crow period in New Orleans, Mobile, Pensacola, and smaller enclaves throughout the Gulf South.

Creoles exemplify the complexity of ethnicity and how ethnic identities can cross and obfuscate social conceptions of racial categories. While long unused in academic circles, the word “mulatto” may still be heard among older generations in the South and still makes surprising appearances in popular films and music in the 21st century. Mulattos were regarded as a product of miscegenation, which referred to unions between whites and blacks, whites and mulattos, or blacks and mulattos and covered anything from single acts of intimacy to marriage. The first series of laws designed to discourage miscegenation passed the Virginia Assembly in 1662. Many Africans and their children were free before 1661, when the Virginia legislature passed laws making Africans slaves for life. By 1691 a European woman who gave birth to a mulatto child was required to pay a fine or, if unable, be sold into servitude for five years and thereafter banished to Barbados. European fathers of mulatto children needed only to do public penance one Sunday in their local churches, and even this practice was short lived as more and more white men sired mulatto children. By 1705 marriages between “white” and “black” persons invoked a jail sentence.

Strictly speaking, a mulatto was a person with one black parent and one white parent. Mulattos had different experiences depending upon the subregions in which they lived. In the Upper South their numbers were significant in the colonial period, and many were free, rural, and of poor or modest means. However, some, such as Sally Hemings, the half sister of Thomas Jefferson’s wife, were tied to the most powerful people in the land. In the Lower South, mulatto populations grew later but had more varied classifications; for example, a “quadroon” was one-fourth black and an “octoroon” one-eighth black. They lived in communities in Charleston and New Orleans and also had considerably more freedom, financial prosperity, and social status than mulattos in the Upper South. Additionally, they more often had sponsorship from white fathers. In New Orleans, through a practice called plaçage, publicly known relationships between free black women and white men lasted long after the man married a white woman. Children took the father’s surname, were supported by him, and could inherit from him. Sons were educated, sometimes abroad in France. Daughters born of plaçage often themselves became mistresses after debuting at “quadroon balls.”

Also in Louisiana, someone who was three-fourths black was considered a “sambo” (“zambo”) or a “griffe.” These terms often referred to a child of a mulatto and a black person, or an American Indian and a black person. Elsewhere in the South, especially in South Carolina, a child of American Indian and black parentage was called “mustee,” derived from the French mestis (métis) and Spanish mestizo. Occasionally, this also referred to combined Native American and European ancestries. Someone having seven out of eight great-grandparents who were black might be called a “sacatra” or a “mango.” These terms emerged when people thought that culture and character were transmitted “in the blood,” so that people of mixed descent posed a perceived social danger and often formed isolated and cohesive communities, some of which endure to the present.

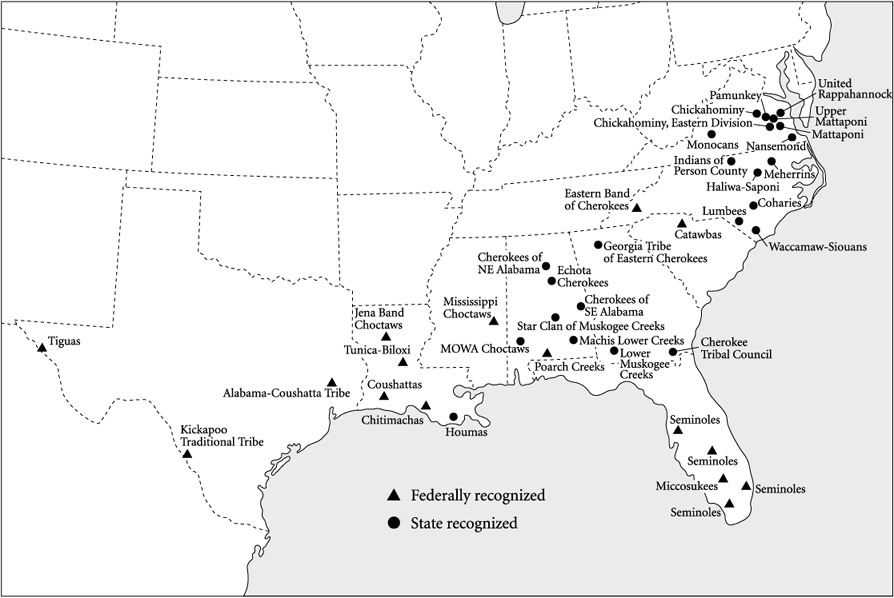

Under Jim Crow, American Indian groups with mixed ancestry were variously unacknowledged, self-segregated, or classed with African Americans. Some such groups originated in the 17th and 18th centuries, when many American Indian chiefdoms had collapsed and towns and linguistically related groups tended to coalesce and gradually mingle with European and African populations. The Houma of the traditionally francophone areas of Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes of Louisiana perhaps had this experience. They are one of many populations across the South that were neither “black nor white” during the Jim Crow era and are denied recognition by the federal government as American Indians today. The original Houma in Louisiana were displaced by the Tunica, and over the centuries they intermarried with European Americans and African Americans. Their ethnic identity now defies racial categorization. In the last census, almost 7,000 people self-identified as Houma.

Many similar groups (called “triple-mixes” by younger members) with American Indian, African, and European ancestries survive in pockets across the South, including the Melungeons of eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina; the Brass Ankles, Santees, and Turks of South Carolina; the Red Bones of Louisiana; the Guineas of Barbour and Taylor Counties in West Virginia; and the Ahoskie Blues of northeastern North Carolina’s Hertford County. Not being black, white, or Indian, they often found themselves disdained by all three groups. Some “passed” as white or black and left their home areas. Many communities have long denied their ethnicity. However, in an age of multiculturalism, some members (usually those whose parents or grandparents had moved away from the original settlement areas) have begun to embrace a resurgent ethnicity and to claim a once-stigmatizing ethnonym as their own rather than as an imposed category.

Now identifying themselves as having American Indian, African American, and English, Scots-Irish, Tunisian, Portuguese, or other Mediterranean ancestry, Melungeons in the 1990s began holding reunions, publishing cookbooks, and promoting historic preservation efforts and heritage tourism to Turkey (another possible ancestral homeland). South Carolina’s Turks, sometimes called Free Moors, have a more specific origin story, tracing their ancestry to one man “of Arab descent,” Joseph Benenhaley, who fought with General Thomas Sumter in the American Revolution.

At times multiple ethnonyms existed for these groups—some more overtly disparaging than others, and some more comfortably euphemistic. Mountain people sometimes referred to their German neighbors as “Dutch” (for their language, Deutsch), so that Melungeons in eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina, where many Germans had settled, were also called “Black Dutch.” Some Brass Ankle communities in South Carolina preferred to emphasize their American Indian roots and call themselves “Santees.” These Creole groups problematize the usual binary categorization of “race.” Their ethnonyms’ self-ascription, or their application by outsiders, relates also to class and politics. Many communities and individuals lost more complex identities in the legal black/white caste system created by Jim Crow laws in the 1890s.

New South–Era Immigration. How did centuries of cultural creolization give way to the dichotomized society of the 20th century? After the Civil War and the end of slavery, social institutions and new laws prioritized “race” over class and ethnicity. The population of Brazil (where slavery lasted from the 16th century until 1888) has a far larger percentage of people with African ancestry than the United States. Brazilians also utilize over 500 recorded racial labels that are not applied through hypodescent, but are more flexibly related to a person’s changing phenotype (one appears lighter or darker depending on recent exposure to the sun, standing in the shade, the time of day, etc.), so that even full siblings may belong to different “races.” With so many intermediate categories, hypodescent rules did not develop in Brazil to keep “blacks” and “whites” separate. In the South, the antebellum color vocabulary (quadroon, octoroon, griffe, etc.), which reflected changing perceptions of difference as binary, passed mostly out of use in the 20th century. Segregation into “colored” and “white” carved separate domains in public facilities and buildings such as buses and trains, restaurants, restrooms, hotels, theaters, and even cemeteries. During Reconstruction, southern African Americans organized their own churches (which eventually fostered the civil rights movement). American Indians likewise set up their own churches and also church-sponsored schools rather than have their children attend segregated African American public institutions.

Despite such efforts to maintain their Indian identity, many groups faced legal attempts to abolish their peoplehood. Perhaps the most severe, and preposterous, actions were sponsored by Virginian eugenicists who wished to prevent miscegenation and limit access to white schools. The Racial Integrity Law of 1924 passed by the Commonwealth of Virginia (and not repealed until 1968) implemented a system of racial documentation to class all state residents as colored or white. Implementing the law meant denying the existence of any Indians in the state (despite their association with the oldest reservation lands in the country, granted in colonial treaties) and claiming that descendants of Pocahontas and John Rolfe were “white” and not Indians after all.

If indigenous peoples were denied their ancestral identity under Jim Crow–era legislation, what type of categorization did new immigrants face? Unlike Caribbean immigrants in the early 19th century who held a range of identities in relation to color and ancestry, “multiracial” immigrant groups, such as the Cubans, found themselves divided into separate categories in the South despite a shared nationality. As early as 1831, Cubans were making cigars in Key West. In the 1880s Vicente Martínez Ybor brought Cuban cigar manufacturing to Tampa, where Cubans founded Ybor City. More Cubans and Afro-Cubans arrived as exiles following the War of Independence from Spain (1895–98). Cuban writer José Martí had recruited support in Ybor City for that revolution (in which he died). Just over a century ago, Cuban immigrants founded the MartíMaceo Society (a mutual aid, social, and Cuban independence group) in honor of both the Euro-Cuban Martí and an Afro-Cuban hero, the revolutionary general Antonio Maceo. The society quickly divided at the turn of the 20th century along color lines. About 15 percent of the Tampa Cuban community at the time was Afro-Cuban, and they faced different assimilation challenges than other Cubans. In Florida, Afro-Cuban immigrants found a society in which they were separated from Euro-Cubans by Jim Crow laws and from African Americans by culture, language, and religion. “White” Cubans joined the El Circulo Cubano (the Cuban Club), and the two groups have yet to reunite even though, today, cousins sharing the same great-grandparents have memberships in different societies.

For several decades after the Civil War, new immigrants to the South settled on one side or the other of a single color line, but they did not encounter the organized nativism that new immigrants did in the North. Nativism—the political or social expression of hostility toward immigrants based on ethnicity, religion, class, politics, economics, or social constructions of race—had never developed in the South during the antebellum era as it did in the North because new immigrants were few outside urban areas, and they assimilated quickly. In the early New South period, southerners rejected nativist movements because of their association with the Republican Party and because southern state governments actively sought new immigrant labor. While Germans and Irish were treated as different “races” in the North, they did not arrive in large enough numbers in the South to provoke a similar interpretation or negative response (nor did the small groups of Slavic or Polish immigrants who came south). Southern Italians, however, were sometimes deemed black, and 11 Sicilians were lynched in New Orleans in 1891. Some scholars have argued that early 20th-century southern nativism against Sicilians and Jews (including the 1915 Atlanta lynching of Leo Frank) was more class- and economic-based than ethnic, but with the post–World War I xenophobia that swept the nation, the 1920s South adopted religious and racial nativism. The reborn Ku Klux Klan played on anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish sentiments as well as color prejudice. However, remarkably few new Catholic or Jewish immigrants came to the South compared with other regions as the New South remained financially devastated well into the 20th century.

Despite efforts to attract new immigrants to the region, the vast majority chose the industrial urban areas of the North or the farmlands of the Midwest and West. Some Swiss, Slavonians, Czechs, and Hungarians settled together in ethnic communities in the South, and some Irish joined older Irish communities in New Orleans, Savannah, Memphis, Charleston, Mobile, Richmond, and Augusta. By 1905 Italians had arrived in Lambeth and Daphne, Ala., and had come to Tonitown, Ark., and Texas to work in cotton and rice cultivation. Italians also took work in the sugarcane and strawberry fields of Louisiana and Mississippi. Construction on the Texas railroads attracted Chinese, who also worked in the cotton fields of Mississippi and Louisiana. Those newcomers to the postwar South started fresh in a region with the lowest standard of living in the nation.

In 1936 famed regionalist Howard Odum published Southern Regions of the United States, in which he analyzed social and demographic characteristics of the South compared with other regions. The economic legacy of the Civil War meant that the gross annual income of the average southern farm in the 1920s was half or less (under $1,500) that of farms in Iowa, North Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska, Montana, California, Nevada, or Arizona. In comparison with working wages across the country in 1929, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina had the lowest annual income on average (under $800). Sixty-five years after the Civil War, southern farms were the smallest in the nation—most averaging under 75 acres. Georgia and Florida had a slightly higher average, closer to 75–100 acres, but only Texas had farms closer in size to those of the western and northwest central states (150–300 acres); this partly explains why Texas attracted a higher number of immigrants in the postwar period, including Czechs, Bohemians, and Italians. However, Texas was more like the rest of the South in that fewer than 10 percent of its farms had tractors, and the percentage of its population living on farms (40 percent or more) was the greatest in the country. The South, then, had high percentages of its population living on the smallest and most underequipped farms, and making the lowest incomes from their farms, in the nation. Odum noted that between 50 and 90 percent of southern children suffered from inadequate diets leading to rickets, anemia, and the carious teeth found in about 50 percent of the schoolchildren examined. Such conditions were not what motivated immigrants to cross an ocean, and they kept European immigration to the region dramatically low.

Odum calculated that “foreign-born whites” constituted at least 17.5 percent of the population of the Northeast and between 12.5 and 17.5 percent of the populations of states such as California, Nevada, Washington, Montana, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Michigan, but that less than 2.5 percent of the white population of the southern states was foreign born in 1930. (Outside the South, only New Mexico and Oklahoma had a similar lack of new European immigrants.) Florida, such a magnet for Eastern Europeans in the late 20th century, had only 2.5 to 7.5 percent foreign-born whites, still making it the only state in the South with over 2.5 percent. Odum noted that the greatest numbers of African Americans were in the southern states, a statistic that remains true today. While seven cities in northern and midwestern states had African American populations of over 50,000, only southern states had black populations composing more than 10 percent of the state population in 1930. Mississippi’s population in that year was over 50 percent African American, and Texas and Tennessee were the only southern states to have populations that were less than 26 percent African American.

Many southern states saw their percentage of African Americans decrease during the mid-20th century, in part because of exodus. However, this trend just as quickly began reversing with African Americans’ return to the South. Since the mid-1990s, 8 of the top 10 metropolitan areas nationwide with black populations exceeding 200,000 are in the southern region. Florida was a favored destination of African American “returnees” to the South in the 1970s, attracting almost 16,000 new African American residents between 1975 and 1980, followed by a fourfold increase between 1985 and 1990. Orlando added 20,000 African American residents between 1995 and 2000 (a growth rate of over 60 percent in that segment of the city’s population), slightly more than Atlanta. In the last two decades African Americans have been more likely than European Americans to resettle in the southern region, and Georgia and North Carolina have also had especially high growth rates.

Because the South did not receive the numbers of immigrants the rest of the country did after the Civil War, creolized southern identities are some of the oldest American identities. Many black and white southerners have ancestry in the region reaching back multiple centuries. This—coupled with the fact that the U.S. Census does not indicate a date range for answering its ancestry question—in part explains why southern states had the highest numbers of persons reporting their ancestry as “United States” or “American” on the 2000 census. This identification was more common for southern states than one of the three groups most frequently self-reported for ancestral origins across the nation (German, Irish, or English, in that order). California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas were the only states in the country in which more than 1 million people reported their ancestry as American. Perhaps because of Texas’s border with Mexico, the influx of Mexican immigrants, and the accompanying emphasis on national identity, over 1,554,000 Texans claimed American ancestry alone on the 2000 census—more than in any other state (Texas also led the nation in this category in 1990). On the 2000 census, “American” was the most-reported ancestry group as a percentage of the total state populations in Tennessee, Arkansas, Kentucky, and nonsouthern West Virginia. Over 20 percent of Kentuckians listed “American” for their ancestry, as did 17.3 percent of Tennesseans and 15.7 percent of the population of Arkansas.

That said, the censuses also strongly reveal the panoply of ethnic groups (old and new) across the South. On the 1990 census, 47 percent of those self-identifying as “Scotch-Irish” (Scots-Irish) were from the South. Of the four states whose largest ancestry groups were Irish on the 2000 census, two were in the South (Arkansas and Tennessee). Nationally, the highest percentages of African Americans remain in the Deep South. In 2000, 36 percent of Mississippi’s population was African American, followed by Louisiana (32.5 percent), South Carolina (29.5 percent), Georgia (28.7 percent), and Alabama (26 percent). The South has 69 percent of the nation’s Cuban Americans, 91 percent of its Acadian/Cajuns, 40 percent of its Hondurans, and over 40 percent of its Haitian immigrants and Haitian Americans.

Late 20th- and 21st-Century New Southerners. The largest numbers of new immigrants to arrive since the colonial period have come to the dynamic and economically sound South of the latter 20th century. After President Lyndon B. Johnson’s southern-focused War on Poverty, the South’s economic boom, and national immigration reform, the South has become particularly attractive to new immigrants who reflect current processes of globalization. Greeks and Irish continue to settle across the South, and Sudanese and Somali immigrants fleeing civil war in their homelands are establishing communities in Nashville and Atlanta; however, the bulk of the new southerners are not from Africa or Europe, but from South and Central America, the Middle East, and Asia. The 1965 Immigration Reform Bill abolished the national origins quota system and particularly favored Latin American and Asian immigration. Over the next decade almost 25 percent of new immigrants to the United States came from Asia and almost 40 percent came from Latin America (from 1980 to the mid-1990s, almost 35 percent came from Asia and over 45 percent came from Latin America).

The foreign-born population of the South quadrupled in the four decades prior to the year 2000. Atlanta is the nation’s ninth-largest metro population and one of its fastest growing. When the first edition of the Encyclopedia of Southern Culture went to press in 1989, close to 25 percent of the metro Atlanta population was minority; by 2005 that figure was closer to 40 percent. Florida has the highest percentage of foreign-born residents (16.7 percent of its total population) and also has attracted migration from ethnic groups within the country. It is now home to one of every two people of Italian ancestry and to two of every three Jews living in the South. In numbers of foreign-born residents, Florida is followed by Texas (14 percent of its population is foreign born), Georgia, and North Carolina. Howard Odum noted that in 1930 Georgia had only 47 employed persons who were Mexicans, and North Carolina had only 10. The changes in the span of one lifetime are dramatic: the 2000 census records 224,000 (foreign-born) Mexican immigrants in Georgia and 199,000 in North Carolina, with some counties in each state experiencing between 200 to 400 percent increases.

Current demographic changes in the South make discussion of a biracial South outmoded. After the Southwest, the South has the highest proportion of Hispanics/Latinos in the nation. The Census Bureau considers “Hispanic” to mean a person of Latin American descent (including persons of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, or Central and South American origin) living in the United States who may be of any “race” (which the bureau oddly defines as “White,” “Black or African American,” “American Indian,” “Asian,” etc.). The term “Hispanic” refers to the influence of Spanish language and culture. “Latino” arose in the late 1980s and 1990s to emphasize the indigenous cultures and identities of Central and South America independent of Spain (many Latinos have Indian identities in their nations of origin). Across the nation in the 1990s, the Hispanic population increased by 57.9 percent (at a time when the U.S. population on a whole saw an increase of 13.2 percent). Hispanics now compose a larger proportion of the American population than do African Americans. Despite these trends, the general public, the media, and academics remain comfortable discussing the labels “black” and “white” as a kind of default categorization of all things southern. Although such a categorization of the region is intellectually habitual, it is shorter lived than the history of the South and is month by month becoming more passé.

The surge in North Carolina’s Latino population over the last decade is in part due to the North Carolina Growers Association and other employers recruiting thousands of workers through the 1989 federal H2A “guest worker” program. Prior to the 1990s the state’s farmworkers were predominantly African American. They are now 90 percent Latino—a rapid demographic change apparent in other southern states. As African Americans increasingly leave farmwork for service sector jobs, they are replaced predominantly by Mexicans. They are also displaced in poultry plants, other agricultural processing positions, and light manufacturing and construction by Mexican laborers (these trends are also common in Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Alabama). In addition to documented guest worker program recruits, perhaps 50 percent of migrant laborers in North Carolina are working illegally. Their numbers are much more difficult to confirm, as are the percentages of such guest workers who remain and make the South their permanent home. As the labor force has changed, wages have declined. Neither expecting nor demanding benefits, Mexican laborers have accepted such low wages that the average farmworker in North Carolina now earns less than $8,000 a year.

Before the recent surge of Mexican immigrants, Cubans had been one of the largest, and oldest, Latin American groups in the South. In the 2000 census, two-thirds of all Cubans in the United States live in Florida. Old enclaves such as Ybor City remain. Today, Ybor is within the metropolitan area of Tampa and is still home to Cuban social clubs, Catholic churches, grocery stores, bakeries, and Cuban restaurants such as the Columbia. Opened in 1905 by Cuban immigrant Casimiro Hernandez Sr., the restaurant seats 1,700 guests, features flamenco dancing performances, and serves favorite Cuban dishes such as yellow rice and chicken, boliche, and flan. Ybor still has a residential area, but the main street shopping area is now an art district and a popular venue for weekend nightlife. A statue of an immigrant family stands in Ybor’s Centennial Park, and a museum to cigar factory workers is located near preserved workers’ cottages. Many Cuban Social and Mutual Aid Society buildings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries remain (El Pasaje, or the Cherokee Club; El Centro Asturiano, a society for both Italians and Cubans; and the Cuban Club).

Descendants of these early Cuban immigrants to Tampa remain ethnically aware, but they were quickly upwardly mobile and became quite distinct from newer Cuban communities in south Florida. After the Castro revolution of 1959 and until the mid-1970s, approximately 16,000 Cubans risked their lives to come to Florida as balseros (on homemade rafts) without permission from the Cuban or American governments. Many more came in the famous 1980 Mariel sealift. The last large influx of Cubans came in 1994 when Fidel Castro announced that anyone wanting to leave Cuba was free to do so. Faced with assimilating the over 35,000 Cubans who did, the U.S. government returned rafters collected by the U.S. Coast Guard to Cuba.

Fourth and fifth generations of the Hernandez Gonzmart family who operate the Columbia Restaurant in Tampa, Fla. The original restaurant opened in 1905 as a corner café frequented by Cuban cigar workers (Photograph courtesy of the Columbia Restaurant)

South Florida Cubans remain deeply committed to political goals for their homeland and to bringing relatives to the United States, as sadly demonstrated by the 2000 case of Elian Gonzalez, a six-year-old boy who was returned to his father in Cuba after his mother drowned trying to bring him to Florida. Cubans have transformed Miami into a Cuban city in a relatively short time. Once the destination of Yankee developers, Miami is now the center for Caribbean culture in America. Calle Ocho (Eighth Street) features Cuban restaurants, freshly squeezed guarapo (sugarcane juice), late-night mambo music, and salsa and merengue dancing. In Hialeah and Little Havana in Dade County, specialty shops and caterers provide dresses and festive Cuban foods for quinceañera parties (coming-of-age celebrations for 15-year-old girls). Diverse religious practices from Cuba also characterize Cuban populations in south Florida, including Santeria (the Way of the Saints). Estimates suggest that 90 percent of Cuban Jews came to the United States in the 1960s. Approximately 5,000 to 6,000 Hispanic Jews live in Miami. Members of the Circulo Cubano-Hebreo (the Cuban-Hebrew Social Circle) emphasize themes of homeland and diaspora from Cuba in their ethnic identity.

In 2000 Florida had one of the largest non-Mexican Latino populations in the nation. Although Puerto Ricans have established communities in every southern state since 1980, more live in Florida than in any other state in the region. South Florida has the largest Nicaraguan population outside Managua, and Nicaraguans are perhaps the second-largest Hispanic population in south Florida. Fleeing political upheaval at home, Nicaraguans are ethnically diverse. Those of Miskito identity descend from indigenous Nicaraguans who speak their own language in addition to English and Spanish and mostly come from the Atlantic Coast. Creole/Miskito Nicaraguans speak English and often Spanish, were missionized by Moravians, and their community in south Florida remains organized around the Moravian Prince of Peace Church in Miami. Of Nicaraguan immigrants to Florida, the Creoles came earliest, beginning in the 1950s, and many are now professionals. Mestizos speak Spanish primarily, are Catholic, and come from the Pacific Coast of Nicaragua. Most arrived only after the Sandinistas came to power in 1979, but estimates of their population in the Miami area reach as high as 400,000. In south Florida the various Nicaraguan ethnic groups mix less with each other than with other Latinos. They often live in neighborhoods with Hondurans and Costa Ricans, but also near Salvadorans and Guatemalans.

New groups of immigrants from the Central and South Americas are shaping new identities in the South with members of other Latino nations, with Jamaicans, Haitians, and other Caribbean new southerners, and through their assimilation with preexisting southern ethnic groups. The next few decades will see the emergence of new Creoles and mestizo cultures in the South’s subregions. The 1970s saw some of the first Spanish-speaking Protestant churches in the South, and just 30 years later, Latino evangelicals outnumber Episcopalians and Presbyterians in the South. In North Carolina and other southern states, Roman Catholics outnumber Methodists (one of the three main evangelical denominations in the region). Fiestas are becoming as common on the southern cultural landscape as barbecue cook-offs, peanut festivals, and blue-grass jamborees. Across the South, annual Hispanic festivals—like the Gran Fiesta de Fort Worth, the Fiesta Latina in Asheville, N.C., the Hispanic Festival in Augusta, Ga., and the Festival Hispano in North Charleston, S.C.—are also increasingly appealing to non-Hispanic participants. The character of such festivals demonstrates how immigrant communities assimilate to the southern region and also gauges how our perceptions of what is “southern” continue to evolve.

The U.S. Census reveals that the Asian population of the South grew dramatically in the latter half of the 20th century. The Census Bureau’s “Asian” category racializes what are very distinct ethnic identities by subsuming Asian Indians as well as Chinese, Filipinos, Nepalese, Japanese, and Samoans and other Pacific Islanders into the same category, and it is important to note which particular South and East Asian groups have favored the South. While East Asians more commonly settled in California and Hawaii, since the 1970s Filipinos, Koreans, Vietnamese, Hmong, and Asian Indians have been immigrating or migrating to the South so rapidly that close to 20 percent of all Asian Americans now reside in the region. (This figure is almost double the number in the Midwest and about the same as the percentage in the Northeast.) Asian Americans now constitute approximately 4.2 percent of the American population, and this national average was exceeded in one southern state (Virginia has 4.3 percent). However, in only nine states did Asians represent less than 1 percent of the total population, and three of those were in the South (Alabama, Kentucky, and Mississippi).

Nationwide, South Asian Indians are one of the top-five immigrant groups in the early 2000s after Mexicans and along with Filipinos, Chinese, and non-Mexican Latin Americans. Indians also form some of the most highly educated immigrant communities (about 70 percent have a college degree and 40 percent have a master’s degree or doctorate). Arriving mostly after immigration reform in 1965, Indians have one of the highest per capita incomes for any ethnic group and have become a significant presence in the medical, engineering, technology, and computing professions as well as the hotel industry. Texas, Georgia, and Florida have developed particularly significant populations, but Hindu temples dot the southern landscape from Baton Rouge to Nashville to Richmond, and celebrations of India’s Independence Day are making appearances across the region. Houston is home to multiple Hindu cremation service providers, at least 20 sari boutiques, 15 Indian-owned hair salons, and 20 jewelers in addition to numerous Indian groceries and over a dozen video stores that import the latest Bollywood productions. Known as the Bible Belt or the Sunbelt, the South also has been called the “beauty pageant belt,” and first- and second-generation immigrants sponsor an annual Miss India Georgia pageant in Atlanta (the subject of a 1997 documentary). Dallas, Houston, and other southern cities also hold annual Indian and South Asian beauty pageants.

South Asia includes India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Burma (Myanmar), but many immigrants from varied nations and cultures join Indian American communities in the United States. When India alone has over 500 distinct languages and five major religions (Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, and Jainism), diversity is thus reduced by embracing a “South Asian” identity in a new land. In 2005 the University of Florida established the country’s first Center for the Study of Hindu Traditions. (The only other center of its kind globally is at Oxford University in England.) Numerous Indian American associations exist across the South from Austin, Tex., to Columbia, S.C., and at many universities.

Until the arrival of Korean war brides and adopted war orphans in the 1950s, the Chinese of Texas and the Mississippi Delta were the earliest and most significant East Asian presence in the South. Most Koreans coming to the South came after the 1965 immigration reform and settled in urban areas, where they own small businesses or work in manufacturing or professional and technical fields. Between the 1990 and 2000 censuses, the Korean population of the South grew nearly 53 percent. Virginia is home to the largest number, followed by Georgia and Florida. While many arrive directly from Korea, others are moving south from the American West. Korean Baptist churches are increasing in numbers, while Korean Presbyterians constitute one of the fastest-growing Protestant denominations in the South.

The Vietnam War, of course, spurred Vietnamese immigration to the United States. After California and Texas, Louisiana, with its Catholic French heritage, was a particularly attractive destination for immigrants from a former French colony. One of the largest Vietnamese enclaves in the United States is the Versailles community in New Orleans, home to multiple Vietnamese churches, Buddhist temples, and Vietnamese groceries. Approximately 12,000 Vietnamese lived in New Orleans in the early 2000s. Many Vietnamese also settled along the Gulf Coast of Mississippi in the early 1980s to work as fishers and in seafood plants. Many of the estimated 10,000 Vietnamese in the area have opened successful restaurants and coffeehouses.

With a population of 135,000, the Vietnamese are the largest East Asian group in Texas, followed by the Chinese and the Filipinos, the latter of whom number to 60,000 in that state. The first significant Filipino immigration to Texas followed the Spanish-American War in 1898, when the United States acquired the Philippines. Many immigrants to the United States at that time chose Texas because of its climate. After World War II, Filipino men who had served in the U.S. armed forces could become citizens, and some of them immigrated to Texas. English had long been one of the Philippines’ official languages, and Filipino professionals familiar with the language quickly followed. Filipino Texans have formed their own ethnic associations and continue to teach their children Filipino art, embroidery, dance, and musical forms, but they also have long joined in wider community events—for example, by sponsoring floats in the Fiesta San Antonio. Nationwide, Filipinos are one of the largest immigrant groups, and in two southern states they compose the largest percentages of East Asian populations: in Florida they number just over 54,000 and in Virginia almost 50,000. The next-largest Filipino populations in the South are in Georgia (11,000) and North Carolina (almost 10,000).

The Japanese have come south quite slowly. By 1940 a few hundred Japanese were living as rice farmers in Texas, but no other concentrated communities were noted in the census of that year. Two of the World War II internment camps for Japanese Americans, holding more than 15,000 people, were located in Arkansas, but the vast majority left at the war’s conclusion. The 1950 census recorded only 3,000 in the South. Today, North Carolina alone is home to over 5,600 Japanese Americans, almost twice as many Filipinos, 12,600 Koreans, 15,600 Vietnamese, more than 18,000 Chinese, and over 26,000 Asian Indians.

Muslim Arab Americans have also become more visible in the South in the last few decades, although Christian Arab and Middle Eastern Americans have been a part of southern communities since the late 19th century. Florida and Texas are home to Syrian and Lebanese Americans whose ancestors immigrated between the 1880s and the 1940s. During that time period, most immigrants called themselves “Syrian” (Lebanon only achieved independence in 1946) and came to the rural South for farmwork or to establish businesses in Atlanta, Birmingham, New Orleans, and eventually Miami. Now called “Lebanese Americans,” the descendants of these original immigrants constitute a significant proportion of Arab Americans living across the country. Ten percent are from a variety of Muslim sects, while the majority are Christian. Their churches include the Chaldean Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Maronite, and Melkite, and in the South many Arab Americans have joined Roman Catholic as well as Baptist and Methodist congregations. Jacksonville, Miami, Palm Beach, and Tampa have some of the largest communities in Florida, and Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio are home to those in Texas. In Vicksburg, Miss., the focus of the Lebanese community is the St. George Antiochan Orthodox Church. In Mobile, Ala., some of the best-known Lebanese surnames include Kahalley, Kalifeh, Saad, Sudeiha, Naman, and Zoghby.

From 1990 to 2000 the Arab population increased by over 50 percent in North Carolina and Virginia and by almost 60 percent in Florida. In 2000, 26 percent of the Arab population in the United States lived in the South. While Arab Americans have more commonly settled in urban areas of California, New York, and Michigan, three southern states have become home to new, large Arab American populations: Florida foremost, followed by Texas and Virginia. The Arab American populations of Florida and Texas have more than doubled since the 1980 census, in part because of a growing presence of Egyptians, Jordanians, and Palestinians. Having a smaller population than Florida or Texas, Virginia has nonetheless quadrupled its Arab American population since 1980, largely because of the immigration of North Africans. More than 8,000 Kurds live in Nashville (more than any other American city) and affectionately call their new home “Little Kurdistan.”

Arab Americans place a strong emphasis on education, and almost 40 percent obtain a bachelor’s degree (compared with the national average for Americans of 24 percent). In many cases, new Arab Muslim women immigrants are more likely to assimilate aspects of southern and American culture than are males. Many Muslim women live as professionals in America yet, within their ethnic communities, are expected to succumb to cultural visions of their inequality if they maintain a faith that does not readily syncretize. Rejecting (for women) many of the opportunities that immigrants have intentionally sought, some Muslim men have attempted to erect physical barriers in front of women’s prayer space in southern and Appalachian mosques. Young women have instead made attempts to blend their faith with southern traditions. In 2005 the first recognized chapter of the Muslim sorority Gamma Gamma Chi was established in Alexandria, Va. A chapter is also planned for the University of Kentucky in Lexington (a city with a Muslim population of almost 2,500) to blend studying the Koran with sisterhood.

As immigrants do around the world, new immigrants to the South often maintain links with their homeland. They frequently foster the immigration of friends and extended family to join them in their new home. They may also import religious practitioners, educators, and performers of the expressive arts to teach their children their own cultural traditions and to create a focus for a community with other nationals. Many immigrants save money to send to relatives in the homeland and to return there for visits. When people maintain a cultural identity and social, economic, and political links to their homeland but establish a new home abroad, social scientists refer to the processes involved as “transnationalism.” Immigrants from the same country may have had different ethnic identities within their home nation states but, finding a newly shared ethnic identity with other nationals in a new land, create social and benevolent associations to foster community and assist recent arrivals. The form and focus of transnational communities entails particular worldviews and shapes the extent to which a new immigrant group assimilates and new syncretized cultural forms develop.

Of the many groups now establishing transnational communities in the South, some have been more surprising to their new neighbors than others. Nationwide, Hmong immigrants from Laos (by way of Thailand) have earned the reputation of the “least assimilatable” immigrants. They have settled in specially chosen communities across the rural South in towns like Mount Airy, N.C., and their animistic traditions (sometimes involving the slaughter of animals in the front yard or the living room of rented apartments) have provoked astonishment. However, many Hmong immigrants have also joined local Christian churches or formed their own congregations. In Mount Airy, Andy Griffith’s hometown, they enjoy their new community’s annual Mayberry Days festival, which celebrates the Andy Griffith Show. Haitians have burgeoning populations in south Florida and the Carolinas. Miami has received the most immigrants of rural peasant backgrounds. To support Vodou rituals in Miami’s working-class Little Haiti, goats and poultry are brought from agricultural markets as far away as south Alabama. Yet, many immigrants from Haiti are middle-class and are also successfully integrating into Floridian society at the highest levels. In 2001 Josaphat (Joe) Celestin became the first Haitian-born mayor of a U.S. city, the city of North Miami. In 2000 Phillip Brutus became the first Haitian-born elected representative to the Florida legislature, and Fred Séraphin, a native of Haiti, is now a judge in the Miami-Dade County Courts system.

In addition to new Asian and Latino immigrants, the 21st-century South also attracts newcomers from nations whose immigrants either have not traditionally sought a home in the region or whose predecessors had come before only through slavery (south Florida, for example, now has Icelandic and Igbo cultural associations). In the early 2000s, Eastern Europeans, especially those from Ukraine, Poland, and Russia, have the highest rates of immigration (among Europeans generally) to the United States, and increasing numbers are coming south. Since the terrorist attacks of September 2001, longer Immigration and Naturalization Service processing times for popular destinations such as New York City and Washington, D.C., have led to more immigrants choosing southern cities such as Nashville, Tampa, and Charlotte. Charlotte, a city of slightly more than 600,000, has over 65 ethnic associations engaging, among other groups, French Americans, Arabs, Iranians, Jamaicans, Cambodians, Somalians, Finns, Turks, Ethiopians, Welsh, Armenians, Nubians, Eritreans, and Ecuadorians. Among African immigrants to the United States, Nigerians have had the highest numbers in the early 2000s. After New York, Texas attracts the most Nigerians of any state, and of the 12 top destinations for new arrivals, Georgia ranks sixth, Florida seventh, and North Carolina eleventh. Ethnic identities such as Igbo, Hausa, and Yoruba (just the most prominent of hundreds of ethnic groups in a nation created by colonial administrators rather than from within) remain strong in Nigeria and translate into distinct cultural associations across the Atlantic. However, despite a recent history of ethnic civil war (1967–70) in their native land, even these newcomers sponsor a united and national Miss Nigeria U.S.A. Pageant out of Atlanta.

Current studies of globalization focus on economic and social trends that enhance the mobility of people, the exchange of ideas, and the rapid increase in communication and trade internationally. Anthropologist James Peacock has noted that current trends in globalization are in some ways a return to colonial and post-Revolutionary patterns. Southern ports linked trade routes between North America, the Caribbean, Europe, and Africa, constituting early globalization in the 17th and 18th centuries. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the South was less globally and more regionally focused on an identity and way of life that was in contrast to what was “northern.” In the later 20th century, as cultural dualism evolved to pluralism and now multiculturalism, the South reglobalized through commercial exports such as Coca-Cola, CNN, Bank of America, Delta Airlines, and FedEx, through the export of political leaders such as Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, and through the reception of new southerners from around the world. Global influences are now reshaping the South and southern identity as they once shaped the colonial region. This volume offers a sampling from the four centuries of immigration, creolization, and ethnic life that have forged, and continue to define, the South and its many subregions.

CELESTE RAY

University of the South