Southern Appalachia and Mountain People

As a subregion of the South, the Appalachian South has forged its own unique identities. Mountain inhabitants historically have been ethnically diverse and are increasingly so today. The three bands of southern Appalachia—the Allegheny-Cumberland (parts of West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama), the Blue Ridge (parts of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia), and the Great Appalachian Valley (parts of Maryland, Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama)—have been the subject of their own extensive mythology disconnected from that of the Old South. Novelist Lee Smith expressed the cultural dissimilarities between the Lowland South and southern Appalachia when she described her mountain home as “far from the white columns and marble generals.” In terms of outsiders’ perceptions, she noted: “Appalachia is to the South what the South is to the rest of the country. That is: lesser than, backward, marginal, Other.”

Beginning with the introduction of outside interests cutting timber, mining coal, and establishing manufacturing industries in the 1880s, local color writers and missionaries have popularized images of southern Appalachia that still shape stereotypes of the region and the ways in which “mountain people” see themselves. From “uplift literature” portraying the region as a social problem, to romantic and fanciful theses about residents’ feuding, supposed Elizabethan dialects, and fallacious status as the most “Anglo-Saxon” of all American populations, outsiders have represented distorted images of Appalachia to serve their own purposes. The fiction of Mary Noialles Murfree (1850–1922) and the local color writings of Emma Bell Miles (1879–1919) and Horace Sowers Kep-hart (1862–1931) were sympathetic to mountain people, but they still helped formalize myths about Appalachian people as static anachronisms. John Charles Campbell’s The Southern Highlander and His Homeland (1921) was one of the first works of systematic scholarship that to some extent documented diversity within the region, but it was nevertheless shaped by a missionary agenda. Journalists, tourists, and educators wrote accounts of their forays among people they deemed “the last frontiersmen” who entertained them with folktales, “ancient” ballads, and the use of “archaic” language. By the turn of the 20th century, the charming frontier people image had been replaced by the more lasting and harmful stereotype of superstitious, incestuous, lazy, whiskey-distilling hillbillies. The efforts by both CBS and NBC television networks to produce hillbilly “reality shows” in the first few years of the 21st century demonstrate how such degrading perspectives still appeal to the public imagination outside the region and still foster a particular self-consciousness among mountain people.

Mountain people are known for their egalitarianism and individualism, their firm connections to place and extended family, and their dedicated church attendance. The Mountain South is home to a proliferation of evangelical denominations with Methodists, heterogeneous Baptists, and Holiness-Pentecostal churches being the most common. Although the region is named for the Appalachee Indians, today the Cherokee and other Native Americans now com-southern appalachia and mountain people prise only 0.3 percent of the Appalachian population. The majority of southern Appalachian people (about 85 percent) are descendants of the two most predominant ethnic groups to displace American Indians late in the colonial period: the Scots-Irish and the Germans. These settlers came down the Great Wagon Road from Philadelphia to what was then called the Backcountry. In some states, Scots-Irish constituted half or more of the European settlers in Appalachia, which remains an area where some of the largest numbers of people self-identify as such on the U.S. Census. It is these immigrants who created bluegrass music with acoustic stringed instruments (British and Irish fiddle traditions, combined with acoustic guitar, mandolin, upright bass, resonator, or Dobro, guitar, and African-derived banjo), who left the region the legacy of the Hatfields and McCoys, who preserved the rich tradition of British ballads and Jack tales (the latter made famous in recent years by the Hicks family), and who maintained weaving traditions (taught in Appalachian “settlement schools” a century ago and today at Berea College in Kentucky and Crossnore School in North Carolina). Southern Appalachian foodways are a blend of American Indian, British, and German traditions, and vernacular architecture styles merge Scots-Irish, English, German, and Scandinavian adaptations to the backwoods frontier.

Mountaineer with his two grandsons, Breathitt County, Ky., 1940 (Marion Post Wolcott, Library of Congress [LC-USF34-055706-D], Washington, D.C.)

Scholars once considered mountain folk the cultural descendants of what historian Frank Lawrence Owsley called “the plain folks of the Old South”—predominantly yeoman farmers with few or no slaves. However, hierarchy and slave ownership were a part of southern Appalachian society, and the “father of Appalachian Studies,” Cratis Williams, observed that internal socioeconomic diversity undermines generalizations about the region. He noted that while southern Appalachia was home to the town dweller, the valley farmer, and the branch water mountaineers (“hollow folk”), stereotyping targeted the latter and was extended to everyone living within the geographic area. The Mountain South had a mixed farming economy with small farms and reliance on hunting and open-range livestock grazing, but as timber and mining companies acquired land and mineral rights, profits left the region, taxes soared, and many farmers could no longer make a living from, or retain, their land (a process that continues today with wealthy outsiders building extravagant summer homes and resort communities). If some antebellum mountaineers could be considered middle-class “plain folk,” their standard of living actually declined in the postbellum economy and with “modernization.” Many farmers took mill work or went to the coal mines, which provided a slim livelihood, dangerous working conditions, and black lung disease. The mechanization of coal mining and the closure of many mines led to high unemployment and entrenched poverty, so that Appalachia remains one of the poorest regions in America. As part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, Congress created the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) in 1965 to further social and economic development in the region and create or expand highways to decrease isolation. Today, southern Appalachia is still predominantly rural, with few cities and many government forests and parks. It still has some of the highest rates of working poor in the nation. Residents usually take on wage labor while also keeping subsistence gardens, Christmas tree farms, or fruit orchards. Many mountain folk work in tourism-related occupations. Southern Appalachia’s population is growing at a higher rate than that of northern Appalachia, in part because of immigration and in-migration.

Southern Appalachia and its people have been the subject of speculation, romance, prejudice, and scholarship since the late 19th century, but in 1977 a group of teachers, scholars, and regional activists began the Appalachian Studies Association to encourage research and improve communication between Appalachian people, their communities, and governmental and educational institutions. Many association scholars are natives and have taken the ongoing national biases against Appalachian people to task. Redressing the negative representation of mountain people, they also have found that even when positive ethnographic and historical accounts of southern Appalachian life have appeared, these have still rendered all but the “Anglo-Saxon frontiersmen” invisible. In the last two decades, scholars have begun to address the ethnic diversity of the mountain population and document the ways in which new immigrants from Latin America and Southeast Asia continue to add to mountain culture.

While African Americans arrived in the mountains first as slaves, free blacks had also settled in the region by 1790. Historian Richard Drake has noted that, although the majority of antislavery societies in the United States prior to 1830 were in southern Appalachia and Unionist sentiment was strong there during the Civil War, a slave-owning elite did exist in many counties. Generally, the Mountain South had smaller populations of slaves, with many areas having black populations of under 1 percent. The only Appalachian county to have a 50 percent black population at the beginning of the Civil War was Madison County, Ala. At the end of the 19th century, newly freed slaves came in search of work in the coal mines. Today, African Americans comprise about the same proportion of the population of southern Appalachia as they do the total U.S. population (12 percent), but they comprise only 2 percent and 3 percent, respectively, of the populations of central and northern Appalachia. According to the ARC, most African Americans in southern Appalachian counties live in towns rather than rural areas, with the largest concentration being in Jefferson County, Ala., which encompasses the city of Birmingham.

A group of Kentucky performance poets have coined a new ethnonym, “Affrilachian,” to describe African American mountain people. The Beck Cultural Center in Knoxville, Tenn., features displays on African American history in eastern Tennessee. Berea College in Kentucky, the first interracial college in the South, established a Black Cultural Center in 1983. The Highlander Folk School founded by Miles Horton in 1932 in Monteagle, Tenn. (now the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tenn.) was engaged in activism during the southern labor movements of the 1930s, the civil rights movement from the 1940s to the 1960s, and the Appalachian people’s movements of the 1970s and 1980s and was visited by Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. In Colored People: A Memoir (1994), Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates has written of experiencing desegregation where he grew up in the company town of Piedmont, W.Va. African American recording artists playing traditional Appalachian music include Etta Baker, “Sparky” Rucker, and the old-time string band Martin, Bogan, and Armstrong. The first “Black Banjo: Then and Now Gathering” took place at Appalachian State University in Boone, N.C., in 2005.

Appalachia attracted ethnic Protestants such as French Huguenots, Welsh Baptists, and French-speaking, Italian Waldensians (Waldenses) from the Cottian Alps of northern Italy. In 1893 over 200 Waldensians settled Valdese, N.C. Their unique Protestant religious heritage predates the Reformation and caused their forebears centuries of persecution, but after a century in the Mountain South many have now become Presbyterians and Methodists. Nineteenth-century settlers brought with them distinctive Alpine architectural traditions, and many of their structures are now of historic interest for visitors to Valdese. Traditional ciders, wines, and foods, in addition to particular stories, French hymns, and games such as bocce, also feature in the annual Waldensian Festival held each August.

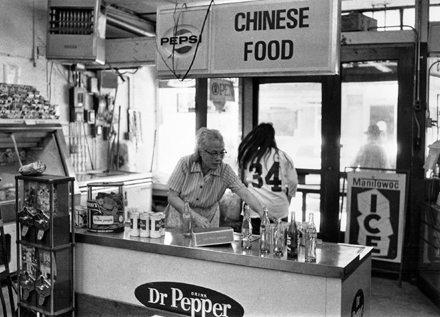

Although Eastern and Southern European immigrants came to work in the coal mines between 1890 and 1910, southern Appalachia did not attract significant new immigrants until the latter 20th century. Buncombe County, N.C., has now become home to close to 100 resettled Ukrainians. Since 2000, nearly half of the region’s new residents are from minority groups. Thousands of Hmong (tribal people from the mountains of Laos who fought with the U.S. military in the Vietnam War) have been resettled in western North Carolina since the 1980s, adding a new dimension to life in small towns such as Mount Airy (population 8,000 and famed as Andy Griffith’s hometown and the home of “Siamese twins” Eng and Chang Bunker). Hmong were attracted to Mount Airy to work in its hosiery mill, and when the mill closed, many have moved again. As with many Hmong resettlements, the Hmong at Mount Airy rapidly became U.S. citizens but kept to themselves. They are reluctant to acculturate and, although they sometimes attend local churches, they have caused consternation by sacrificing chickens to the spirits within the living rooms of their public housing projects. Marrying young and producing large families, they maintain ties with Hmong in other towns, with many gathering at a large settlement in Hickory, N.C., for their major holiday, Hmong New Year.

Hispanic immigration has been rising rapidly across the South, and the Mountain South is no exception. Construction work, apple and cherry orchards, vineyards, poultry plants, and nurseries have all offered employment opportunities. Throughout the region, the number of classes offering English as a second language has grown tenfold since 2000. Many Hispanic immigrants are living in the United States illegally and, not being classed as refugees like the Hmong, find obtaining citizenship a long process. However, Hispanics are more likely to get involved in the local community and to also establish their own Catholic churches, businesses, and stores.

Leaving their homeland during the civil war of the 1980s and 1990s, Guatemalan Maya have immigrated to Morganton, N.C., and to Appalachian communities in Georgia and Alabama, where they settle together with others from their home villages. After an initial immigration period, spouses and relatives, schoolteachers, and practitioners of traditional arts soon follow. Many younger male Mayans are engaged in farmwork, the nursery or poultry industries, or work for resort communities. With other Latino immigrants, Guatemalan Mayans are renting and buying houses in small towns that had previously experienced depopulation and changing the face of the Mountain South and what it means to be “of” southern Appalachia.

CELESTE RAY

University of the South

Allen W. Batteau, The Invention of Appalachia (1990); Patricia Beaver, Rural Community in the Appalachian South (1986); Patricia Beaver and Helen Lewis, in Cultural Diversity in the U.S. South, ed. Carole Hill and Patricia Beaver (1998); Dwight Billings, Gurney Norman, and Katherine Ledford, eds., Confronting Appalachian Stereotypes: Back Talk from an American Region (1999); Harry M. Caudill, Night Comes to the Cumberlands (1963); Wilma Dunaway, Slavery in the American Mountain South (2003), The First American Frontier: Transition to Capitalism in Southern Appalachia, 1700–1860 (1996); Ron Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers: Industrialization of the Appalachian South, 1880–1930 (1982); Elizabeth Englehardt, The Tangled Roots of Feminism, Environmentalism, and Appalachian Literature (2003); Leon Fink and Alvis E. Dunn, The Maya of Morganton: Work and Community in the Nuevo New South (2003); Wilburn Hayden, Journal of Appalachian Studies Special Issue: Appalachia Counts: The Region in the 2000 Census (2004); Kirk Hazen and Ellen Fluharty, in Linguistic Diversity in the South: Changing Codes, Practices, and Ideology, ed. Margaret Bender (2004); Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (2004); Elvin Hatch, Appalachian Journal: A Regional Studies Review (Fall 2004); Benita Howell, ed., Culture, Environment, and Conservation in the Appalachian South (2002); C. David Hsiung, Two Worlds in the Tennessee Mountains: Exploring the Origins of Appalachian Stereotypes (1997); John C. Inscoe, Mountain Masters, Slavery, and the Sectional Crisis in Western North Carolina (1989); ed., Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation (2001); Terry Jordan and Matt Kaups, The American Backwoods Frontier: An Ethnic and Ecological Interpretation (1989); Mary LaLone, in Signifying Serpents and Mardi Gras Runners: Representing Identity in Selected Souths, ed. Celeste Ray and Eric Lassiter (2003); Deborah McCauley, Appalachian Mountain Religion: A History (1995); W. K. McNeil, ed., Appalachian Images in Folk and Popular Culture (1989); Frank L. Owsley, in The South: Old and New Frontiers, ed. H. C. Owsley (1969); Mary Beth Pudup, Dwight B. Billings, and Altina L. Waller, eds., Appalachia in the Making: The Mountain South in the Nineteenth Century (1995); Henry D. Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870–1920 (1978); Nina Silber, in Appalachians and Race, ed. John C. Inscoe (2001); Robert P. Stuckeret, Journal of Black Studies (March 1993); William H. Turner and Edward J. Cabbell, eds., Blacks in Appalachia (1985); David Whisnant, All That Is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region (1983), Modernizing the Mountaineer: People, Power, and Planning in Appalachia, revised ed. (1994); Jerry Wayne Williamson, Hillbillyland: What the Movies Did to the Mountains and What the Mountains Did to the Movies (1995).

Southerners

The 21st-century South is home to many ethnic groups, but since at least the 19th century some in the region have tried, with little success, to establish white southerners as having a particular ethnic heritage, first as cavaliers and more recently as Celts. Beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, sociologists (most importantly John Shelton Reed) and historians (most prominently George Brown Tindall) took a new approach. Influenced by an increasing national interest in ethnicity, aware that the region’s distinctive social system based on a rural one-crop economy and rigid system of white supremacy was rapidly passing, yet convinced that despite such changes a “South” would persist, Reed, Tindall, and other scholars proposed that southerners be looked upon as an ethnic group. Proponents of “southerners as ethnics” realized that the concept of “ethnicity” did not fully fit the southern experience and so sometimes labeled southerners as “quasi-ethnics” or wrote of employing an “ethnic analogy.” The analogy proved inexact because the South had never been a nation, although Reed pointed out it had at least been a failed one. Nevertheless, the concept of southerners as ethnics took hold as a useful way to describe the amorphous yet persistent notions of southern identity and distinctiveness. By 1980 southerners even commanded an entry in an encyclopedia of American ethnic groups.

Tindall and others who employed the concept of ethnicity saw its potential to define “southernness” in a way that would acknowledge that African Americans had played a central role in the creation of the region’s culture and that could provide an identity that embraced both blacks and whites. More recently, other scholars have endorsed the idea of southerners as ethnics as a means to include not only whites and African Americans, but also other groups. The new proponents build from the idea of the South as a persistent folk culture and stress the creole nature of that culture. They celebrate diversity within the region, where the early proponents of southerners as ethnics often sought to identify southerners’ shared distinctiveness.

In both cases, the idea of southerners as ethnics rested in southerners’ sense of their own identity; most thought of and identified themselves as “southerners,” albeit with varying degrees of intensity, and perceived that people outside the region did as well. Beyond the sense of a distinctive identity, Reed, Tindall, and other early proponents of southerners as ethnics built their case on two different but obviously interrelated bases: history and culture. In the first, southern ethnicity was rooted in a distinctive past: slavery, the Confederacy, a rural post–Civil War social order built on a one-crop economy, a one-party political system and disfranchisement, and rigid segregation. The region’s historical experience did not so much live on in memories of specific events (even southerners’ knowledge of the Civil War proved surprisingly shallow) as it did in a generalized sense of grievance. The region, southerners maintained, had long been mistreated and looked down upon by the North. Basing southern ethnicity in history, though, undermined the idea of an identity shared by blacks and whites. Although proponents pointed to a common, if tragic, racial past, the attitudes of white and black southerners toward the region’s racial history and the persistent division along the color line led Tindall and others to argue that the region held not one but two ethnic groups: black and white.

The second basis offered for southern ethnicity—culture or a core of shared beliefs and practices—could more often unite black and white. In addition to their sense of grievance, southerners widely shared three beliefs that distinguished them from other Americans: a strong sense of and pride in place, deeply held conservative religious beliefs, and a ready acceptance of personal violence rooted in a traditional sense of personal honor. Proponents of a southern ethnicity also pointed to a strong attachment to family and various other forms of behavior. Language—not just a pronounced accent but different dialects and a proclivity for certain usages (“y’all” and “mama,” among others)—marked southerners as an ethnic group. So, too, did distinctive tastes in foods, among them grits, okra, fried green tomatoes, and MoonPies. A few observers even included such phenomena as country music and stock car racing, both of which had their roots in the region. The rise of both to national popularity at the beginning of the 21st century, however, raises questions about the persistence of southerners’ distinctive ways, as does the discovery that by that time only about a quarter of southern adults claimed to use “mama” and even fewer regularly ate grits. Perhaps the pervasive power of modern American popular culture will eventually overcome many aspects of southern ethnicity. Proponents of the idea of southerners as persistent ethnics would counter that the South is always changing but never disappearing.

GAINES FOSTER

Louisiana State University

James C. Cobb, Redefining Southern Culture: Mind and Identity in the Modern South (1999); Lewis M. Killian, White Southerners, revised ed. (1985); Celeste Ray, ed., Southern Heritage on Display: Public Ritual and Ethnic Diversity within Southern Regionalism (2003); John Shelton Reed, The Enduring South: Subcultural Persistence in Mass Society (1972), Southerners: The Social Psychology of Sectionalism (1983); George Brown Tindall, Journal of Southern History (February 1974), Natives and Newcomers: Ethnic Southerners and Southern Ethnics (1995).

Afro-Cubans

“Afro-Cuban” (afrocubano) is a term that was invented by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz in the early 20th century. Those whom the term designates often suggest it fails to capture the nuances of Cuban history and seems to qualify citizenship in the nation that Cubans of African descent were instrumental in creating. Historically, the African population was proportionately much larger in Cuba than in the United States. Expanded sugar production in 19th-century Cuba rested on the labor of African slaves. Yet there were many more free people of color in Cuba than in the South under slavery. Afro-Cuban mutual aid societies (los cabildos de naciones) enabled retention of African languages and fostered syncretic Afro-Catholic religions (e.g., Santeria). African-derived music and folklore have strongly influenced Cuban popular culture. Afro-Cuban music has enjoyed sustained popularity in the United States. Dizzy Gillespie’s mid-20th-century collaboration with Cuban musicians Tito Puente, Mario Bauza, and Celia Cruz helped establish a strong audience for salsa. Drums and metaphors from African religious traditions flavor this musical genre, which continues to draw broad interest. One example is the Buena Vista Social Club, a Cuban ensemble reviving a classic era of Cuban popular music and composed partially of the musicians who played in a prerevolution dance club of the same name.

More than half of the soldiers in the Cuban revolt against Spain in 1895 were black or mulatto. It was during this revolution (and the earlier revolt of 1868) that Afro-Cubans first migrated to Florida and Louisiana. Cigar production in Key West and Tampa attracted Cuban settlers. Afro-Cubans accounted for about 15 percent of these 19th-century Cuban migrants. Smaller settlements of cigar workers located in Jacksonville and New Orleans. In addition to cigar workers, these early communities included a large number of Cuban intellectuals and political figures prominent in exile political organizations.

The end of the war against Spain in 1898 coincided with the rise of Jim Crow laws in the United States. Afro-Cubans were adversely affected by these laws. Segregated social clubs formed. Sociedad La Unión Martí-Maceo (the Martí-Maceo Society, founded in Tampa in 1900 in honor of José Martí and Antonio Maceo, important leaders in the Cuban fight for independence) still remains in existence, as does El Círculo Cubano, the white Cuban club founded in 1899. The leading centers of Cuban settlement in the United States during the early 20th century, Ybor City and West Tampa, were enclaves with elaborate social, recreational, and political organizations. Afro-Cubans were integrated into these enclaves, but with growing distance from white compatriots.

Cigar-worker migration to Florida slowed during the Depression of the 1930s and ended completely with the 1961 embargo against Cuban tobacco imports. The very large influx of anti-Castro Cuban exiles, beginning in 1959, targeted Miami far more than Tampa; the Cuban histories of Key West and Jacksonville were by then nearly forgotten. Fewer than 10 percent of the immediate post-1959 immigrants were Afro-Cuban. Second- and third-generation Afro-Cubans in Tampa became more isolated, cut off from contact with Cuba and increasingly involved with African Americans.

The 1980 “Mariel boatlift” (a mass exodus of Cubans prompted by a downturn in the Cuban economy and having the sanction of Cuban president Fidel Castro) included a much larger proportion of Afro-Cubans, many of whom remained in Miami. More recent waves of immigrants and refugees on rafts have continued to include Afro-Cubans. Despite an increase in numbers, however, black Cubans of Miami have remained spatially and socially separate from white Cubans. Jim Crow and southern patterns of residential segregation explain only part of this phenomenon. The issue of racial diversity among Cubans has a long history of ambivalence. José Martí, who sought national unity and an end to Spanish rule in the 1890s, urged Cubans to ignore racial differences and forget past injustices. However, this sanction discourages discourse about racial problems and has made Afro-Cubans relatively invisible.

Average incomes of Cuban immigrants exceed those of all other Latino ethnic groups in the United States. Black Cubans, however, have been shown to earn significantly less than their white counterparts. In Miami, especially, segregation between black and white Cubans is greater than for the population as a whole. Nevertheless, among recent immigrants and their children, there remains a strong identification with Cuba, and cultural elements such as food and music continue to favor the homeland. In Tampa, descendants of immigrants are more varied in identification and cultural preferences. Fewer speak Spanish or regularly eat Cuban food. Many still attend the St. Peter Claver Catholic Church, and a smaller number continue to belong to the Martí-Maceo Society. The majority of descendants, however, more strongly identify as African American.

SUSAN D. GREENBAUM

University of South Florida

Alejandro de la Fuente, A Nation for All: Race, Inequality, and Politics in Twentieth-Century Cuba (2001); Susan Greenbaum, More than Black: Afro-Cubans in Tampa (2002); Guillermo Grenier and Alex Stepick, eds., Miami Now! Immigration, Ethnicity, and Social Change (1992); Pedro Perez Sarduy and Jean Stubbs, eds., Afro-Cuba: An Anthology of Cuban Writing on Race, Politics, and Culture (1993).

Alabama-Coushattas

The Alabama-Coushatta Tribe includes over 1,000 members, about 500 of whom live on a reservation of approximately 4,600 acres in east Texas. As a Southeastern Woodlands group, the Alabama-Coushatta trace their ancestry back to the Mississippian moundbuilders and belong to the Muskogean linguistic family, which also includes the Creek, Choctaw, Seminole, and Chickasaw. They encountered Hernando de Soto during his 1539–41 expedition, when he visited Alabama and Coushatta towns in northeastern Mississippi, northern Alabama, and southern Tennessee. By the late 1600s, the two groups had moved to the area of present-day Montgomery, Ala. There they participated in the Upper Creek Confederacy. By the mid-1700s autonomous yet interconnected Alabama and Coushatta towns began migrating independently from Alabama. Some groups settled in parts of Louisiana and Florida before crossing into Texas in the 1780s. The contemporary Alabama-Quassarte town in Oklahoma represents groups who were removed from Alabama in the 1830s. The Texas tribe maintains some contact with the Oklahoma group and closer ties with the Coushatta tribe of Louisiana.

The Alabama and Coushatta peoples negotiated relationships with the colonizing French, Spanish, and English and, later, with Americans, Texans, and Mexicans who vied for political and economic alliances with both tribes. Non-Indians such as Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston cited the tribes’ reputations as “civilized,” friendly, and peaceful to prevent their removal from east Texas in the 19th century. In 1840 the Republic of Texas first tried, unsuccessfully, to find reservation land for the Alabama and Coushatta. The state of Texas designated reservation land for the Alabama in 1853, and the Coushatta joined them there.

After the Civil War the Alabama and Coushatta experienced poverty and disease, without federal or state government aid. In 1881 Presbyterian missionaries came to the reservation and pressured the tribe to give up many native practices, but they also provided the education and medical care that the state and federal governments neglected. In the 1880s the railroad brought the lumber industry to east Texas and engaged Alabama and Coushatta individuals in a wage-labor economy. While alleviating poverty, the wage-labor system exacted a cultural toll. However, anthropologist M. R. Harrington documented the significant retention of cultural practices into the 20th century despite assimilative pressures.

During the 1910s and 1920s both the state and federal governments began to give aid to the tribes. In 1928, to increase the size of the reservation, the federal government purchased more land and deeded it collectively to the Alabama-Coushatta. The name has remained hyphenated ever since. After the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Alabama-Coushatta organized as a tribe and created a constitution that prescribed, among other things, strict membership and residence rules.

In 1955 the federal government terminated its trusteeship relationship with the Alabama-Coushatta, thereby transferring the responsibility to the state of Texas. However, in response to a dispute over hunting rights and an adverse ruling by the state attorney general, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe sought and regained federal recognition in 1987.

In the 1960s the tribe began a tourist enterprise with funding from the state of Texas. Today, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe promotes economic development on its own initiative. In 2001 the Alabama-Coushatta began limited gaming with the opening of an entertainment center. However, the state opposed and closed the operation in spite of the drastic increase in jobs and economic improvements that it brought not only to the reservation but to the entire area. The tribe continues to pursue negotiations on gaming with the state.

In the 21st century the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe conducts instruction in native language, pine-needle and river-cane basket making, and traditional dance. Individuals work and attend school in the surrounding area and participate in local Presbyterian, Baptist, and Assembly of God churches. In addition, people maintain the observance of matrilineal clans and traditional medicinal techniques and foodways. Individuals have also revived intertribal networks across the United States through participation in political and business activities, powwows, and athletic events.

STEPHANIE MAY DE MONTIGNY

University of Wisconsin–Oshkosh

Daniel Jacobson, Ethnohistory (Spring 1960); Geoffrey D. Kimball, Koasati Grammar (1991); Howard Martin, Myths and Folktales of the Alabama-Coushatta Indians of Texas (1977); Stephanie A. May, “Performances of Identity: Alabama-Coushatta Tourism, Powwows, and Everyday Life” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 2001), “Alabama and Koasati,” in Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 14: Southeast, ed. Raymond Fogelson (2004); Harriet Smither, Southwestern Historical Quarterly (October 1932); John R. Swanton, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 137 (1946).

Appalachian African Americans

African Americans have a long history in Appalachia. Arriving first in the 18th and 19th centuries as slaves, their numbers remained relatively small until the opening of the coal fields in the late 19th century. The need for miners encouraged a dramatic in-migration of free African Americans from the Deep South.

In West Virginia, the heart of central Appalachian coal country, the number of African American miners increased from just under 5,000 in 1900 to over 11,000 a decade later. By 1930 West Virginia had 22,000 African American miners. In Kentucky, African American miners numbered 2,200 in 1900 and 7,300 in 1930. These miners either followed family members to the central Appalachian region or were directly recruited by coal companies. While dispersed throughout the region, significant numbers of African Americans found their way to Kanawha and McDowell Counties in West Virginia and Harlan County in Kentucky. In the region’s coal towns, African Americans stood on a comparatively equal footing with European Americans, as coal companies strove to maximize profits by keeping racial antagonism low and placing the most skilled workers in the appropriate jobs, regardless of race. As Appalachians, African Americans presently experience the myriad effects of poverty, including the dilapidated housing, low educational attainment, and limited access to health and social services that typify this marginalized subregion. As a minority among mountain people, African Americans additionally suffer the historical consequences of racism.

Joe Thompson at the Black Banjo Gathering, Appalachian State University, Boone, N.C., 2005 (John Maeder, photographer, Appalachian Wanderings)

Any discussion of African Americans in Appalachia relates to a demographic understanding of Appalachia itself. The region, as delineated by the Appalachian Regional Commission in the 1960s, includes counties in 12 states stretching from Mississippi to New York. In the southern, central, and northern subregions, African Americans comprise 13, 2.2, and 3.6 percent of the population, respectively. Of the 1.7 million African Americans living in Appalachia, approximately 76 percent are in the southern subregion, 22 percent are in the northern subregion, and 2.8 percent are in the central subregion. The 10 Appalachian counties with the highest percentages of African Americans are in Mississippi and Alabama. Additionally, those counties with the highest numbers are urban or adjacent to urban areas.

Implicit in any discussion of blacks in Appalachia is their distinctiveness in relation to other African Americans in the South based on their mountain experience and heritage. Practicing religious and musical traditions of their Deep South kinfolk, rural Appalachian African Americans also had ties to industrializing America. These African Americans, however, have largely been ignored in the media and in scholarship. In their “discovery” of Appalachian culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, outsiders stereotyped Appalachian residents as isolated, backward, violent, and, not least of all, Anglo-Saxon. Over the past 20 years the people of Appalachia, including African Americans, have become increasingly critical of their pejorative representation in mainstream America.

Accompanying the rise of “place-based” studies and identity politics in the 1990s, African Americans began actively claiming an Appalachian identity. William H. Turner and Edward J. Cabbell’s Blacks in Appalachia (1985) considered specific African American communities in the mountains and black coal miners. In the early 1990s a Kentucky-based performance group, the Affrilachian Poets, began to give voice to the frustrations of African Americans in Appalachia who feel excluded from historical and contemporary understandings of what it means to be of Kentucky and/or Appalachia. In Pennington Gap, Va., the county’s first school for blacks, Lee County Colored Elementary School, has become the Appalachian African American Cultural Center. The center collects oral histories, photographs, copies of slave documents, and material culture pertaining to the African Americans’ historical experience in the region.

MICHAEL CRUTCHER

University of Kentucky

Dwight B. Billings, Gurney Norman, and Katherine Ledford, eds., Back Talk from Appalachia: Confronting Stereotypes (1999); William H. Turner and Edward J. Cabbell, eds., Blacks in Appalachia (1985); Frank X. Walker, Affrilachia (2000).

Barbadians

In an influential article, historian Jack Greene called Barbados a “cultural hearth” for the southeastern slave states. The Barbadian influence has probably been exaggerated, but English colonists from that island undoubtedly had an important role in causing early South Carolina to resemble the West Indies in several ways. South Carolina’s slavery-dominated plantation economy was later exported through South Carolinians, both black and white, to other southeastern states.

Another historian, Peter Wood, called South Carolina a “colony of a colony.” By 1670, when the first permanent English settlement was made near Charleston, Barbados was already a mature and exceedingly wealthy sugar-producing colony. Land was scarce on the 166-square-mile island, as large sugar “factories” squeezed out opportunities for small farmers and their families. Barbadians played a key role in establishing the newer English colony. Sir John Colleton, who had gone out to Barbados after the defeat of King Charles I’s forces in the Puritan Revolution, apparently took the lead in obtaining the Carolina charter for eight English noblemen. The most important of the eight Proprietors in the settling of South Carolina, Anthony Ashley Cooper, first earl of Shaftesbury, had also owned a Barbados plantation and had other Caribbean interests. Although a Barbadian attempt to settle Carolina in the 1660s failed, some Barbadians joined the successful 1669–70 settling expedition from England.

In South Carolina’s early years as a colony, much of the shipping from England came by way of Barbados. In the beginning, significant numbers of Barbadian free blacks, indentured servants, and slaves moved to the new colony, but the numbers have been inflated by counting people who only passed through Barbados on their way from England to South Carolina. After the 1690s, rice became the staple crop of South Carolina. Slave populations of more than 80 percent and dreadful mortality developed in Lowcountry parishes that shared the names of parishes in Barbados. The slave code, the harshest on the continent, was also modeled on that of Barbados, but the parallels should not be overstated. South Carolina also came to have a very wealthy white elite, but it never became a monocultural economy like Barbados and its plantation owners were never absentee to the same degree.

Three Barbadians became South Carolina governors in its Proprietary era, and emigrants from that island formed part of the powerful Goose Creek faction that troubled the colony’s owners by refusing to stop selling Native Americans into slavery and by trading with pirates. While serving as the third governor in 1672–74, Sir John Yeamans—who earlier had arranged the murder of a man so that he could marry the man’s wife—infuriated the earl of Shaftesbury by selling to Barbados for a profit provisions that were urgently needed in Carolina. The third Barbadian governor, Robert Gibbes, obtained the office of governor by bribery in 1710. London merchants demonstrated that they could also be rapacious colonists in South Carolina’s early years. Given that astonishingly little is now known of the origins of the colony’s early leaders, too much may have been made of the role of the aggressive Barbadians in the formation of South Carolina.

CHARLES H. LESSER

South Carolina Department of Archives and History

Peter F. Campbell, Some Early Barbadian History (1993); Jack P. Greene, South Carolina Historical Magazine (October 1987); Charles H. Lesser, South Carolina Begins: The Records of a Proprietary Colony, 1663–1721 (1995).

Black Seminoles

From the late 17th century through the mid-19th century, slaves who escaped to Florida from the South Carolina and Georgia Lowcountry found homes and allies among the Seminole. The name “Seminole,” in fact, meant “runaway” and had been adopted after the group detached themselves from the Creek Confederacy. The Seminole called the runaway slaves estelusti and considered them free. Black Seminoles lived in separate villages near at least a dozen Seminole towns, the earliest being in the current Alachua, Leon, Levy, and Hernando Counties. While the Seminole held African-born slaves and had enslaved Yamasee Indians who were prisoners of war, they protected these escapees from slave catchers. When estelusti had resided with the Seminole for long periods they became known as maroons, as did the free blacks who had also chosen to settle with the Seminole. Eventually they became Black Seminoles with a blended cultural heritage and a unique history tied to both slavery and Removal.

Black Seminoles (or Seminole Maroons) spoke Gullah and the Muskogee or Mikasuki languages of the Seminole, and they sometimes served as interpreters between the Seminole and English speakers. Some scholars suggest they developed an Afro-Seminole Creole (a blend of Gullah, Spanish, English, and Muskogee). They adopted the brightly colored clothing and the moccasins of the Seminole, often lived in thatched palmetto plank houses of the Seminole architectural tradition, and danced at Green Corn ceremonies; but they also continued their own cultural traditions, such as “jumping the broom” at marriage celebrations and giving their children African-derived names (for example, names based on the day of the week on which the child was born, such as “Cudjo” for Monday and “Cuffy” for Friday) or “slave names” (such as Abraham and Caesar). Originally from Africa’s Rice Coast, Black Seminoles or their ancestors had grown rice on plantations in South Carolina and Georgia and grew rice crops in Florida in addition to raising corn (about one-third of which they paid annually to their Seminole defenders).

During the Revolutionary War the Black Seminoles allied with the Seminole and the British against the colonists, and when Florida was once again under Spanish control (1784–1821) the Spanish employed Black Seminoles to trade with Indians. When Spanish rule ended, some Black Seminoles moved to Andros Island in the Bahamas (where their descendants live today). Others, resisting the U.S. government’s repeated attempts to reenslave them, fought against Andrew Jackson during the First Seminole War (1817–18) and under their own captains with Osceola’s warriors in the Second Seminole War (1835–42).

Juan Caballo, a Black Seminole leader in the Second Seminole War, was known as a “Black Seminole chief” and a freeman of African, Spanish, and Native American ancestry. The majority of Seminoles and at least 500 Black Seminoles were removed to Oklahoma, where they became known as Freedmen. Caballo founded the Black Seminole town of Wewoka there. By 1849 Creek slave traders in Indian Territory had managed to limit the rights of free blacks and Caballo led his people to Mexico, which had abolished slavery in 1829. There, Black Seminoles were known as cowboys and lauded for their military successes against the Comanche and Apache. In 1870 Black Seminoles in Mexico were invited to settle in Texas and serve as scouts for the U.S. Cavalry. Several won the Medal of Honor (the highest military decoration awarded by the United States) and many served as Buffalo Soldiers. Today, Brackettville, Tex., is home to the Seminole Indian Scout Cemetery Association.

In 2000 the Seminole Nation in Oklahoma changed its membership criteria, and most Seminole Freedmen are no longer eligible for enrollment. However, the different descendant populations in Nacimiento in the Mexican state of Coahuila, in Texas, and in Oklahoma retain a sense of identity through oral tradition and through ongoing social and marital links between their communities. Called Mascogos in Mexico, Black Seminoles have blended Mexican, Indian, and African traditions. Those on both sides of the border claim Indian fry bread, enchiladas, hot tamales, sufkee (a cinnamon-flavored hominy dish), and tetta poon (a sweet potato desert) as Black Seminole food-ways. Historically, the populations living in the United States have been more endogamous, while groups in Coahuila have intermarried with Mexicans. For festival occasions, traditional costumes can include calico skirts and bodices for women and feathered turbans and brightly colored hunting shirts for men. One of the largest Seminole Maroon gatherings takes place each September in Brackettville, where English and Spanish speakers mix to the sounds of African spirituals and Tex-Mex music in commemoration of a hybrid cultural inheritance and shared history.

Fourteen-year-old Matthew Griffin of Groveland, Fla., dresses in traditional Black Seminole Indian clothing when giving public presentations on his ancestors (Sherry Boas, photographer, originally appeared in the Orlando Sentinel, August 2005)

CELESTE RAY

University of the South

LILLIAN AZEVEDO-GROUT

University of Southampton

Rebecca Bateman, Ethnohistory (Spring 2002); Jeff Guinn, Our Land before We Die: The Proud Story of the Seminole Negro (2002); Ian F. Hancock, The Texas Seminoles and Their Language (1980); Rosalyn Howard, Black Seminoles in the Bahamas (2002); Kevin Mulroy, Freedom on the Border: The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila, and Texas (1993); Kenneth Wiggins Porter, The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom Seeking People (1996); Richard Price, ed., Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas, 3rd ed. (1997); Scott Thybony, Smithsonian (August 1991); Bruce Twyman, The Black Seminole Legacy and North American Politics, 1693–1845 (1999).

Brass Ankles/Redbones

Prior to the late 1960s, when they fell into disuse, the terms “Brass Ankles” and “Redbones” were the pejorative nicknames of presumably “mixed-race” communities in South Carolina’s Lowcountry and Louisiana’s western hills and plains. The origin of the terms is not known. Generally, the people to whom the terms were applied resented the designations, usually defining themselves as “Indian,” “white,” or sometimes both.

In South Carolina, individual Brass Ankles and a few families passed as “mulatto” or “colored.” But these represented only a minority of the larger Brass Ankle population. During the mid-20th century, anthropologists and sociologists characterized or defined all of the Brass Ankle communities as “tri-racial isolates” (enclaves of multiethnic and interracial culture and descent) and also predicted the demise of such communities. Only South Carolina had populations labeled as Brass Ankles. Today, their primary communities are located near Pineville and Moncks Corner in Berkeley County, around Holly Hill in Orangeburg County, in Ridgeville and Summerville in Dorchester County, and in Jacksonboro, Walterboro, and Smoaks in Colleton County. Starting in the late 19th century, most of these communities developed separate social institutions, especially churches. The state also supported several “Indian” schools in various Brass Ankle locales. Although African ancestry is certainly a component of several Brass Ankle communities, Native American ancestry is well documented for some of the families in Berkeley County, and those living just north of Holly Hill in Orangeburg refer to themselves as “Santees” and maintain an Indian ethnic identity. Those living between Ridgeville and Walter-boro claim descent from a refugee band of Natchez, exiled from Louisiana by the French colonists, who asked for and received Settlement Indian status from South Carolina in 1747. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, several communities organized themselves into Indian associations. Largely through the efforts of these associations to educate the public, the term “Brass Ankle” was virtually abandoned and is seldom heard in contemporary times.

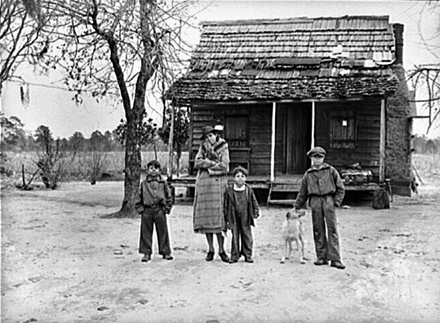

Brass Ankle family at home near Summerville, S.C., January 1939 (Mary Post Wolcott, Library of Congress [LC-USF34-050605-D], Washington, D.C.)

“Redbone” is a more generic term, widely utilized historically across much of the South. Its precise meaning and application varies in time and place, but it always denotes an implication of “racial” mixture. The term has documented usage, particularly in African American speech, in Virginia, Tennessee, and South Carolina, and in Louisiana it came to designate mixed and geographically and socially isolated communities found in nearly every western parish—from Sabine Parish in the north, through Rapides Parish (near Alexandria), and down to Calcasieu Parish in the southwest.

There are perhaps more than 20,000 Louisiana Redbones. Most descend from South Carolinians who were defined as mulattos or “other free persons.” While South Carolinians use the term “Redbone,” its use there generally indicates “mixed-race” persons within the African American community. The westward migration of Brass Ankles and Redbones commenced shortly after the United States acquired Louisiana in 1803. In the new territory, they married into Creole, French, and Indian families, resulting in a unique cultural heritage—at once Anglo, African, Spanish, French, and Indian of several regional tribes. Despite their numbers and dispersal, Louisiana Redbones are largely unstudied. Documentary evidence indicates that at least some Red-bone families are primarily of Native American heritage.

The Brass Ankles and Redbones are prominent examples of the many “little races” that dotted much of the South. Some of these mixed communities have dispersed or disintegrated, their members passing categorically into white and black urban and suburban worlds. Discriminatory forces often fostered a sense of separateness, tighter community ties, and distinct identity. Where effective accommodative leadership emerged, Brass Ankles and Redbones successfully resisted categorization as “Negro” and established their own stores, churches, and schools. Their persistence reveals the variegated ethnic tapestry of the South.

C. S. EVERETT

Vanderbilt University

Virginia DeMarce, National Genealogical Society Quarterly (March 1992); Wes Taukchiray, Alice Bee Kasikoff, and Gene Crediford, in Indians of the Southeastern United States in the Late Twentieth Century, ed. J. Anthony Paredes (1992).

Caddos

Archaeological investigations reveal that Caddo groups were settled throughout valleys of Oklahoma, Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas by 800 A.D. A distinctive culture emerged as Caddos developed a successful horticultural economy, a highly effective political structure, a viable interregional trade network, and well-planned civic-ceremonial centers that were also the scene of elaborate mortuary rituals.

Civic-ceremonial centers employed earthen mounds as platforms for temples and for the burial of social and political elites. Objects unearthed from Caddo sites are rich in symbolism—pottery vessels with distinctive shapes and unique decorative designs, carved stone pipes, sheet copper masks, marine shell gorgets, cups, and dippers. The spiritual leader of all Caddos was the Xinesi, the keeper of an everburning fire whose prayers beseeched Caddi Ayo, “Leader Above,” to forgive Caddo misdeeds and provide for their needs.

Caddo families built large, sturdy homes constructed of vertical timbers, lashed by saplings and cane, daubed with clay, and covered with thatch. An outdoor workspace and elevated corn crib commonly stood near a dwelling. Gardens planted with beans, pumpkins, and sunflowers, fields of corn, and wooded areas separated households.

The earliest written descriptions of Caddo people appear in the chronicles of Spanish and French explorations (after the death of Hernando de Soto, Luis de Moscoso led his expedition and entered Caddo territory in 1542; the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, arrived in Texas in the late 1600s). They describe Caddo farmsteads grouped in dispersed communities with names usually prefixed by “na,” meaning “place of” (e.g., Nadaco).

Young Caddos learning traditional Turkey Dance songs at the drum (Rhonda Fair, photographer)

The chief civil authority for each Caddo community was the caddi, an inherited position. A prestigious caddi might have preeminence over others. Communities were grouped geographically into three separate branches of the Caddo nation. The Natchitoches lived in the area of the present Louisiana city named for them; the Hasinai, meaning “Our People,” lived in east Texas; and the Kadohadacho centered on the great bend in the Red River. “Caddo” derives from the French abbreviation of Kadohadacho, and before the middle of the 19th century only the Kadohadocho were called Caddo.

The Caddo were historically and politically significant during the 18th and 19th centuries, when their homeland became disputed borderland between the Louisiana Territory and the province of Texas. Spanish missionaries, military leaders and government officials, French traders and governors, Mexican presidents, and American Indian agents recognized the powerful influence and political astuteness of prestigious Caddo caddis and vied for the favor of Tinhiouen (caddi ca. 1760 to 1789) and Dehahuit (ca. 1800 to 1833). The Caddos declared neutrality, maintained authority over neighboring tribes in the region, and boasted that no white man’s blood was spilled on their soil.

Strong and gifted leadership could not offset population loss from epidemics or control land grabs by immigrants who advanced the western frontier of the United States. Diminished by disease and plagued by Osage raids, the Caddo moved from the Red River in the 1790s and resettled between the Sabine River and Caddo Lake. The Natchitoches, greatly reduced in number and surrounded by Anglo-Americans, eventually merged with the Caddo and Hasinai. Epidemics subsequently devastated the Hasinai. Survivors in eight formerly populous communities came together in two, Anadarko [Nadaco] and Hainai.

The Caddo were coerced into ceding their Louisiana homelands to the United States in 1835. Treaty terms bound them to move outside the borders of the United States and “never more return to live, settle, or establish themselves as a nation, tribe, or community of people.” Most moved to Texas with in a year. Prevented from establishing permanent villages by Texas militia and frontier people, they were essentially homeless until a Brazos River reserve was opened for them in 1855. Four years later, anti-Indian agitators ignited hostilities that forced them to abandon the Brazos Reserve for Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).

In 2004 approximately 4,800 Kadohadacho, Hasinai, and Natchitoches descendants were enrolled members of the federally recognized Caddo Nation in Oklahoma. Their seat of government is in Caddo County, Okla. An elected chairperson and council replaced the traditional role of the caddi in 1938, but new generations continue to learn ancient Caddo culture embedded in stories, songs, dances, and ceremony.

CECILE ELKINS CARTER

Mead, Oklahoma

Cecile Elkins Carter, Caddo Indians: Where We Come From (2001); Wallace Chafe, “A Note on the Caddo Language,” in Caddo Indians: Where We Come From (2001); Vynola Beaver Neukumet and Howard L. Meredith, Hasinai: A Traditional History of the Caddo Confederacy (1988); Timothy K. Perttula, “The Caddo Nation”: Archaeological and Ethnohistoric Perspectives (1992); Clarence Webb and Hiram Gregory, The Caddo Indians of Louisiana (1978).

Cajuns

Louisiana became a French colony in 1682. The largest concentration of French settlement was in the southernmost part of Louisiana, where French language and culture endure into the 21st century.

South Louisiana is culturally, historically, and linguistically connected to the French-speaking world, but it is hardly homogenous. The great variety of subregional dialects of French derive from three main currents: the colonial French that developed among the descendants of the French who first began to settle Louisiana in 1699, the Creole that developed among the descendants of the African slaves brought to work on the French colonial plantations, and the Cajun French that evolved among the descendants of Acadians who began to arrive in Louisiana in 1765 after they were exiled by the British from their homeland in what is now Nova Scotia. Yet there is little pure linguistic or cultural stock today. The basic sources influenced each other in areas where the groups came into frequent contact. Many move effortlessly and even unconsciously between dialects according to the context. All three basic sources were also modernized by steady trickles of immigration—especially in the 19th century by the so-called petits Créoles, economic immigrants from France, and by refugees from the Haitian revolution—as well as by contemporary academic influences.

Cajun family eating crawfish (Greg Guirard, photographer, courtesy of the Center for Louisiana Studies)

French was the language of everyday life and government in Louisiana into the 19th century. But the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and statehood in 1812 placed serious pressure on French Louisiana to conform to the language and culture of the United States. By the time of the Civil War, there were Acadian generals, governors, bankers, and business leaders. For less upwardly mobile Acadians, the war was simply not their affair. These did not join the effort willingly, and once drafted into the service of the South, they strained to get out of it. Yeoman farmers had no one else to run their farms in their absence, so many simply deserted and walked home from nearby battlefields.

With the end of the Civil War, French Creoles understood that their future was necessarily going to be American; they immediately began to send their children to English-language schools. By the turn of the 20th century, their transition to English was virtually complete. Ordinary Cajuns did not similarly change until much later, beginning with the arrival of Anglo-American farmers from the Midwest in the 1880s and reinforced by the arrival of Anglo-American oil workers and developers from Texas, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania in the early 1900s. This process was intensified by the nationalistic fervor that preceded and accompanied World War I, the relief efforts that accompanied the great flood of 1927, and the agricultural and economic depressions of the 1920s and 1930s—all of which brought national-level relief efforts exclusively in English.

Beginning in 1916, mandatory English-language education was imposed in the southern part of the state in a well-meaning effort to haul the French-speaking Cajuns into the American mainstream. As a result, Cajun children were punished for speaking the language of their parents in school, often by teachers with the same surnames as the students. After World War II, GIS returning from service in France spurred a Cajun cultural revival that was fanned by local political leaders who used the 1955 bicentennial of the Acadian exile from Nova Scotia as a rallying point for the revitalization of ethnic pride. In 1968 the state of Louisiana officially fostered the movement with the creation of the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana, which attempted to establish French as a second language in elementary schools.

Today’s Cajuns are friendly, yet suspicious of strangers; easygoing, yet guarded with their opinions and emotions; deeply religious, yet amusingly anticlerical; proud, yet quick to laugh at their own foibles; and unfailingly loyal, yet possessed of a frontier independence. Cajuns are immediately recognizable as a people, but they defy simplistic definitions.

While the French language struggles to maintain its role in the cultural survival of south Louisiana, the sounds of rock, country, and jazz music are incorporated by young Cajun musicians today as naturally as were the blues and French contredanses of old. New cultural blends continue to emerge in connection with recent Hispanic and Southeast Asian arrivals, including crawfish-filled tamales and egg rolls.

BARRY JEAN ANCELET

University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Barry Jean Ancelet, Cajun and Creole Music Makers, revised ed. (1999), Cajun and Creole Folktales (1994); Barry Jean Ancelet, Jay Edwards, and Glen Pitre, Cajun Country (1991); Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (2003); Carl A. Brasseaux, Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People (1992), The Founding of New Acadia (1987); Glenn R. Conrad, ed., The Cajuns: Essays on Their History and Culture, revised ed. (1983); James H. Dormon, The People Called Cajuns: An Ethnohistory (1983); Marcia Gaudet and James C. McDonald, Mardi Gras, Gumbo, and Zydeco (2003); C. Paige Gutierrez, Cajun Foodways (1992).

Cambodians

Cambodian immigrants in the South are almost exclusively Khmer, the primary ethnic group of their Southeast Asian homeland. The Khmer empire and culture, tracing its origins back more than 2,000 years, experienced an era of greatness during the Angkor period (800 to 1400 A.D.), from which much of contemporary Khmer culture—dance, music, mythology, and Buddhism—derives. Subsequently dominated by a series of foreign powers, Cambodia gained independence in 1954 only to become embroiled in the Vietnam War. The nationalist Khmer Rouge (communist Khmer) seized power in Cambodia in 1975 after the U.S. military withdrew. During the Khmer Rouge’s four-year reign of terror, more than 2 million citizens were executed or starved to death.

Cambodian classical dancers performing Tepmamorom, a dance about harmony, Greensboro, N.C. (Cedric N. Chatterley, photographer)

In the early 1980s, 150,000 Cambodian refugees were resettled in the United States. Data from the 2000 census records a Cambodian population reaching 300,000 and indicates the growth of Cambodian communities in several southern states, including North Carolina (2,681), Georgia (2,905), Texas (6,852), Virginia (4,423), and Florida (2,447). Many Cambodian refugees have been drawn to the South for economic and climatic reasons. Although raised as farmers and fishers, many Cambodians have come to work in furniture factories and textile mills across the South.

For 20 years these new southerners have focused on building new lives, forming Buddhist temples, and reestablishing their annual calendar of ceremonies. Asian markets now nestle within small southern strip malls and stock not only the dried fish, spices, jasmine rice, and cooking utensils used in Cambodian kitchens, but also the incense, candles, and golden statues central to Buddhist religious practice. In communities across the region, language, foodways, storytelling, dance, music, and wedding traditions have also been carefully preserved and passed on to the next Cambodian American generation. Many communities have nurtured traditional Khmer dance groups; Cambodian high school students in traditional silk costumes and gold jewelry perform these classical and folk dances for their friends and teachers during annual International Day celebrations on campus, citywide multicultural festivals, and other public events.

Southern Cambodian communities have reestablished an annual calendar of Buddhist ceremonies that includes major events such as the May celebration of Visakha Puja Day, the day of the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha; the summer celebration of Buddhist Lent and its series of sermons about the life of the Buddha; and the fall Kathin ceremony, in which the congregation presents new robes and personal supplies to the monks. Chol Chhnam, the Cambodian New Year’s celebration, increasingly draws hundreds, even thousands, of participants to temples across the region to recommit themselves to their Buddhist beliefs, offer significant support to the Buddhist temples (wats) they have founded, and to bolster their relationships with other Cambodian families. A national holiday held in the dry season prior to the annual rice plantings in Cambodia, the celebration also includes social games and playful water fights meant to invoke the rains and guarantee good harvests.

While their communities prosper, the current struggle for both first- and second-generation Cambodian Americans living across the South is to craft a new identity that honors both their memories of their ancestral land and their experiences in their new home.

BARBARA LAU

Duke University

May M. Ebihara, Carol A. Mortland, and Judy Ledgerwood, eds., Cambodian Culture since 1975: Homeland and Exile (1994); David W. Haines, ed., Refugees as Immigrants: Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese in America (1989); Barbara Lau, “The Temple Provides the Way: Cambodian Identity and Festival in Greensboro, North Carolina” (M.A. thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2000).

Canary Islanders (Isleños)

Canary Islanders—long known as “Isleños,” or “Islanders”—came from a cluster of 13 Spanish islands off the African coast and entered the colony of Louisiana (then under Spanish rule) between the years 1778 and 1783. They arrived as recruits for the Louisiana Infantry Regiment and to bolster the Spanish presence in the colony. However, Governor Bernardo de Gálvez instead employed the married recruits and their often large families as settlers. Consequently, nearly 2,000 Isleños established themselves in lower Louisiana in St. Bernard Parish virtually adjacent to New Orleans, at Barataria across the Mississippi River from the city, upriver at Galveztown at the junction of the Amite River and Bayou Manchac, and on Bayou Lafourche. Mostly poor and illiterate farmers, they struggled long and hard against adversities such as floods, hurricanes, disease, and poorly allocated settlement sites. By the close of the colonial period, only their St. Bernard and Lafourche settlements survived.

After the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the Isleños, who became the first Hispanic community incorporated into the United States, mostly disappeared. Through the 19th century, they lived in small and isolated enclaves composed principally of Spaniards who preserved their culture and speech, but they were surrounded by larger populations of Acadians, Anglo-Americans, African Americans, and other ethnicities, who rarely acknowledged their culture. Few Isleños improved their economic status and acquired lands and slaves in the antebellum era, and the Civil War destroyed the holdings of most of those who had. In the “Bourbon Age” that followed Reconstruction in Louisiana—when vested interests such as railroad, mining, lumber, cotton, and sugar companies and corrupt planters and politicians in the notorious New Orleans ring dominated political life—a few more Isleños gradually assimilated into Louisiana’s cultural mainstream, acquired an education, and left behind their traditional occupations as farmers, fishers, and hunters.

In the 20th century, modernization brought further change and broke down the isolated enclaves that had retained distinct traditions and the Canarian dialect. Improved means of transportation and communication—railroads, automobiles, paved roads, newspapers, radio, movies, and television—facilitated Isleño assimilation. Twentieth-century wars, especially World War II, spurred mobility and heightened awareness of life beyond the Islanders’ secluded communities. Use of Spanish declined as schools insisted that Isleño children speak only English, and dissatisfied youth often abandoned their “bumpkin” niches to meld into Louisiana’s cultural milieu. Moreover, the Isleños had never practiced endogamy, and with growing assimilation greater numbers married outside their community. Today, few Canary Islanders claim Isleño descent on both sides of their families. The Spanish monoglots typical of the 19th century have disappeared, and their 20th-century bilingual and bicultural descendants who grew up in households where the Isleño language and culture predominated are now elderly and few in number.

Nevertheless, since the 1970s in St. Bernard Parish, where ethnic identity has retained its most enthusiastic followers, members of Los Isleños Heritage and Cultural Society have sought to preserve their cultural past and reacquaint their children with the Spanish language. Leaders in the community established the Isleño Museum and Village, with artifacts and vernacular architecture that recall St. Bernard’s history (another museum has recently opened in Donaldsonville on Bayou Lafourche). In 1996 the Canary Islanders Heritage Society of Louisiana was founded in Baton Rouge. Each spring a festival in St. Bernard focuses attention on Canary Islander heritage, with traditional costumes, typical Isleño foods (based on rice and seafood locally obtained and with a distinctive Louisiana flavor), and the Spanish décima tradition of folk poetry, which relates stories about Isleño life. A few hardy Isleños retain vestiges of the folk medicine, prayers, and related customs brought from the Canary Islands and practiced before the quality of medicine improved and spread to their isolated communities. While Isleños (who are predominantly Catholic) observe Christmas, Easter, and Lent, All Souls’ Day, when tombstones are whitewashed and graves tended, is particularly well celebrated. Finally, in recognition of their singular experience, Louisiana’s Isleños have recently been recognized by the U.S. government as a distinct Hispanic group.

GILBERT C. DIN

Fort Lewis College

Gilbert C. Din, The Canary Islanders of Louisiana (1988); Los Isleños Heritage and Cultural Society, Los Isleños: A Louisiana Local Legacy (2000); Raymond R. Mac-Curdy, The Spanish Dialect of St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana (1950); Dorothy L. (Molero) Benge and Laura M. (Gonzales) Sullivan, Los Isleños Cookbook: Recipes from Spanish Louisiana (2000); Cecile Jones Robin, Remedies and Lost Secrets of St. Bernard’s Isleños (2000).

Catawbas

Members of the Catawba Nation of American Indians numbered 2,423 in the 2000 U.S. Census. While Catawbas live in communities across the country, 500 continue to make their homes on the Catawba Indian Reservation, a 630-acre tract located eight miles east of the city of Rock Hill, S.C., along the banks of the Catawba River. The Catawba reservation sits within the tribe’s ancestral land. It serves not only as the center of tribal political and business affairs, but also as the focal point for preservation of Catawba culture.

When the ancestors of today’s Catawba Indians signed the Treaty of Augusta in 1763, they could not have foreseen the succession of frustrating legal battles that would influence virtually all of their affairs and much of their history. For 230 years, the Catawba filed land claims against the state of South Carolina; eventually, the claims were resolved in the courts and through federal legislation.

Although linguistically related to Siouan peoples, the Catawba of the pre-European contact period shared many of the cultural characteristics of the ancestors of today’s Cherokee tribe. Scholars attribute their blended culture to the tribe’s geographic location in a transitional zone between “hill tribes” (like the Cherokee) and “southern chiefdoms” (like the Waxhaw). Early Catawba cultural characteristics included sociopolitical organization into small tribal groups located in villages situated near rivers; hunting patterns based on seasonal cycles; cultivation of corn, beans, squash, and gourds; pottery making; and spiritual practices associated with the building of burial mounds. The Catawba forged relationships with some neighboring tribes but fought against the Cherokee, who allied with British colonial governments. (The Catawba allied themselves with the Patriots in the American Revolution.)

The Catawba story is one of survival. After contact with Europeans, which began as early as the 1560s and intensified in the early 1700s, members of the tribe sought to maintain their way of life while recognizing that encroaching Europeans had to be accommodated. In the mid-1700s, notable Catawba leader King Hagler skillfully forged alliances with prominent South Carolina citizens and politicians from whom he secured various, albeit insufficient, forms of support. A tragic result of contact with non-Indians was a devastating smallpox epidemic among the Catawba in 1759, which reduced the tribe’s population by 60 percent to a total of 400 members living in a single village. In 1763 the Catawba and South Carolina signed the aforementioned Treaty of Augusta, setting aside the tribe’s 15-square-mile reservation.

In 1840 the state of South Carolina and the Catawba Nation signed yet another treaty, this time at Nation’s Ford, in which the tribe relinquished lands in exchange for promised financial support and a new reservation. The state never made good on these promises and, significantly, the agreement was signed in violation of the Non-intercourse Act of 1790, a law requiring the consent of the U.S. Congress in land transactions involving American Indians.

During the mid-1800s, a time when the federal government forcibly moved eastern tribes westward to Oklahoma Indian Territory, the Catawbas adamantly remained in South Carolina. As early as the 1880s the tribe sought legal redress for the loss of their land in 1840. The late 1800s also saw the arrival of Mormon missionaries in Catawba country, leading to the conversion of many tribal members (most modern-day Catawbas remain Mormon).

On 14 June 1993 Gilbert Blue, the elected chief of the Catawba Nation, and South Carolina governor Carroll Campbell signed an agreement that led to the passage of the federal Catawba Land Claims Settlement Act (signed by President Bill Clinton on 27 October 1993). The terms of the act included restoration of the Catawba Nation’s federal recognition (terminated in 1959) as well as payment of $50 million to the tribe. The act stipulated that the funds be used for land acquisition, economic and social development, education, and per capita payments to tribal members. The settlement has led to cultural preservation initiatives focused on Catawba language, storytelling, and pottery making. Catawbas sponsor reservation-based educational programs for Indians and non-Indians as well as a website that details cultural preservation initiatives. Continued sponsorship of the annual Yap Ye Iswa (Day of the Catawba) festival, as well as some members’ participation in pan-Indian powwows, are additional means Catawbas take to assure their survival as American Indian people and the preservation of their culture for future generations.

JIM CHARLES

University of South Carolina at Spartanburg

Douglas Summers Brown, The Catawba Indians: The People of the River (1966); Charles M. Hudson, The Catawba Indians (1970); James H. Merrell, The Catawbas (1989), Indians’ New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact through the Era of Removal (1989).

Cherokees, Eastern Band

As a consequence of their ancestors’ 19th-century Removal by the U.S. government, the majority of contemporary Cherokees are part of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. However, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians—a federally recognized tribe of about 12,500 members—occupies a reservation of some 57,000 acres in traditional homelands in the mountains of western North Carolina. Its origins date to treaties of 1817 and 1819 that permitted certain members of the Cherokee Nation to separate and reside on private reservations outside the tribal domain. About 50 individuals and their families did so and claimed to be U.S. citizens, though their precise legal status was uncertain. They maintained a traditional Cherokee cultural outlook and continued their association with relatives and friends on the nearby tribal reservation. The 1835 Treaty of New Echota obligated the Cherokee Nation to cede its lands and migrate to present-day Oklahoma, but William Holland Thomas, an Anglo merchant and adopted Cherokee, staunchly defended the right of those holding private reservations to remain, and he helped them acquire additional lands. Neither the United States nor the state of North Carolina attempted to evict these Indians. A few members of the Cherokee Nation hid out in the mountains or otherwise avoided Removal, and they soon joined the Cherokee who legally remained in North Carolina. By 1839 about 1,100 Cherokees lived in the state, with perhaps 300 more in Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama.

Between 1839 and the outbreak of the Civil War, North Carolina Cherokees lived quietly on marginal mountain lands and endured periodic attempts to enroll them for Removal to the West. Had their lands been more attractive to whites, they probably would have been forced to leave. Their way of life blended Cherokee culture with that of their poor white neighbors. They lived as nuclear families in log cabins and raised corn on tiny individual farms, mixed Christianity with Cherokee beliefs and practices, sought consensus in periodic councils, and fiercely competed in the Indian game of stickball. Few of these Cherokees spoke English, and most relied on Thomas to protect their interests. With the coming of the war, Thomas incorporated Cherokee and European American mountaineers into his own Confederate military force, the Thomas Legion. A much smaller number of Cherokee served on the Union side.

Cherokee woman making pottery in North Carolina (Hugh Morton, photographer)