Where the Eye Sees the Eye

The small dinghy crew grunted in surprise, looked back at the Leone in the distance, then squinted again at the ship before them. It sat motionless in the channel, its sails hanging untrimmed. Nobody at all was on deck—it appeared to the sailors to be completely abandoned.

“Er, what do we do now?” one of the men asked the first mate.

The first mate glanced at the two islands and back at the ship in front of them. He nodded straight ahead. “Let us have a look aboard, shall we? Could be easy pickings, it could.” The other men chuckled and resumed rowing. Strange islands gave them the creeps, but an abandoned ship—that was much more to their liking.

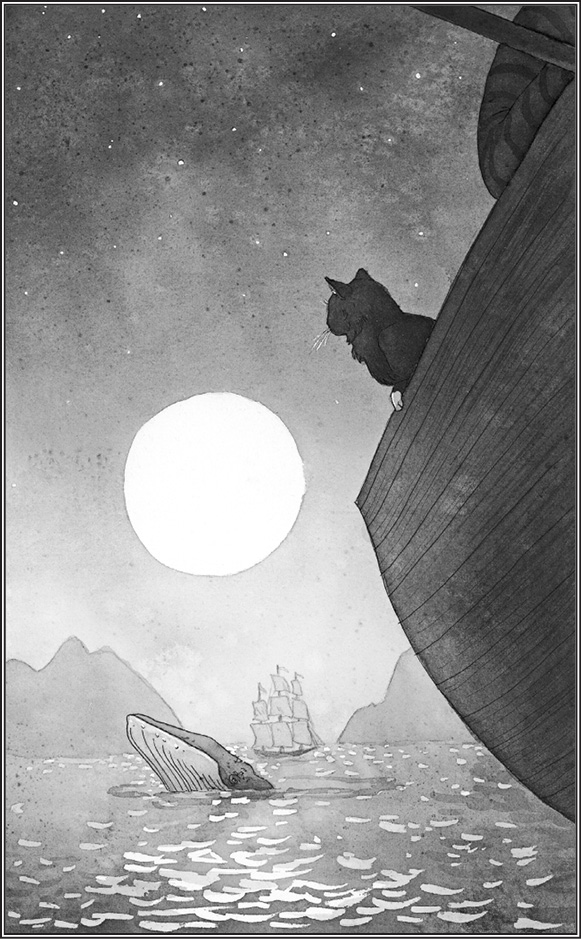

Cecil was infinitely relieved. As the space between the islands came into view he had watched the Eye carefully. It had not moved and now was fixed directly above the ship. He felt sure it had been over the ship all along. From beneath the bowsprit, a blue horse’s head and forelegs surged forward, so it was not the ship Anton had left on, but Cecil still felt strangely drawn to it. The prickling feeling extended to his paws.

As they rowed strongly through the waves, Cecil was the first to notice something moving in the water near the ship, just below the surface, creating a shallow sort of current as it went. Whatever it was moved in a constant slow circle around the ship, the V in the water above it charting its path. Eventually a crewman saw it, too.

“What’s that, eh?” he asked, craning his neck. “Not a shark I hope?”

Oh, cat’s whiskers, thought Cecil with a pang in his belly. I know what that is.

“Dolphin, maybe?” said another.

On the next pass, the first mate saw what Cecil had already figured out.

“It’s a whale,” he said tersely. “Stop rowing. Be still.”

The crew froze in mid-motion, no sound but the lapping of the waves on the sides of the dinghy. Cecil stood on his hind legs with one front paw on the edge, straining to see the whale, wondering if it could possibly be the same one he’d seen twice before. All the fur on his body felt like it was sticking straight out. The whale’s huge head rolled into view, and it seemed to Cecil as if time slowed down. He saw the blue-gray skin and wide white jaw. He saw the deep blue eye with the crust of barnacles over it, looking out, finding him, filling him with that same sensation of wisdom and serenity that he remembered from that day on the schooner so long ago. The eye, thought Cecil with a kind of dreamlike clarity. Then the whale’s eye looked straight up at the mysterious cloud-shrouded Eye in the sky. Cecil let out a little squeak. This is it! he thought. This must be the other eye! The messenger. Of course.

The whale turned and dipped below the surface again, the shallow current changing course and now moving directly toward the little boat. Suddenly the current vanished into a swirling eddy at one spot, and Cecil realized the whale must have dived straight down. One of the younger sailors stood up and screamed in terror, almost swamping them before the others were able to pull him down to his seat again. Cecil kept his balance and watched the water intently, trying to see under the waves.

The whale surfaced forcefully some distance behind them, and the panicked sailors paddled furiously toward the abandoned ship until they were even with it. Two pirates grabbed onto the ropes hanging limply over the side and shimmied up hand over hand, then secured more ropes and threw them over to the others. Cecil steeled himself to try another desperate rope climb, remembering all too well how the one on the side of the Mary Anne turned out, but the first mate swiftly slipped a hand under Cecil’s belly, tucked him into his blue vest, and began to climb up. Shivering and grateful, Cecil looked straight up into the sky to see the Eye above them. The lost shall be found, he thought anxiously, and he wished with all his might that the old saying would turn out to have a little bit of truth to it.

Although Cecil was hopeful about the chances of something good happening on board, the crewmen were decidedly more wary, even fearful. They were a superstitious lot in general, and an abandoned ship was an odd thing for a pirate. On one hand, there was nobody to have to fight and everything available for looting, which was good. On the other, there was the pesky question of why it was abandoned in the first place. Where could the crew have gone? Was there a battle with another vessel? A terrible storm? A plague? Or was it something even more sinister and mysterious—a creature from the deep with many eyes and long tentacles, attacking the ship and making off with every last passenger? They would never know, but these kinds of thoughts made the dinghy crew tread carefully about the ship, speaking in low voices and glancing behind themselves often.

Cecil, however, jogged briskly from deck to deck searching for evidence of any living being. As soon as he had wriggled out of the first mate’s vest and dropped onto the wooden planking, he thought he caught a familiar scent. Very faint and washed out, but here somewhere. The main deck was curiously empty of the usual stacks of barrels and crates. A feeling of vague alarm grew in his brain with a fog of worry.

The pirates found a stash of shiny implements to eat and drink with and stuffed them into bags, as well as clothing and a few small swords. Cecil paced impatiently until they opened the hatch to the hold, but there was no smell of Anton down there, and Cecil began to wonder if he wanted to find his brother so badly that he had imagined the scent to begin with. In the galley, two crewmen were rummaging through the shelves when Cecil stepped in.

“Why, would you look a’ that,” said one, pointing to a tall water barrel with a wire clasp on the top. “Gnawed clear through, ain’t it?” he said, fingering a rough hole in the face of the barrel. A pool of water had gathered on the floorboard.

Cecil stared at the hole in the barrel as well, with a sinking feeling in his bones. That looked like the work of some rodent to him. If Anton were here, he wouldn’t have let mice run wild on his ship. Cecil turned and trotted up to the main deck again. He searched the map room, peered down into every coil of rope, even climbed the rigging all the way up to the crow’s nest in case Anton had been stranded up there, but it was just as unoccupied as everyplace else. Cecil looked up and found the Eye again, floating mildly in the misty clouds. It seemed more distant now, though surely he was closer to it, and in his frustration he felt as if it mocked him with its presence. Where is he? he thought furiously at the Eye. Tell me what to do now! But the Eye merely glowed silently.

Making his way slowly back down the lattice of rigging, which was much more difficult than climbing up, Cecil crossed the deck and went back below. He could hear movement in the hallway of the officers’ quarters. In the largest room, with piles of rolled-up maps on the table and a fine long coat hanging on a stand, Cecil found his rescuer and another sailor on their knees on the floor, trying to pry open a large sea chest.

“It’s no use, sir,” said the sailor, leaning back on his heels and breathing heavily. “We can’t budge it.”

The first mate rested one elbow on his knee and noticed Cecil sitting quietly in the doorway. “And what of you, Lucky Black?” he asked Cecil. “Where’s your luck now, eh? Supposed to be findin’ somethin’, you are.”

Cecil gazed at the man. He had no idea what he was saying, but it was clear that he was interested in the chest. Cecil stretched his neck, looking over the problem, and saw that the lid was carved all over with fishes, just like the one he’d once opened. To the surprise of the men, Cecil leaped on top of the chest and began pressing and pressing the fish with his paws. The first mate laughed and said, “Well, it seems our Black has gone fishing,” but Cecil ignored him. Was it this one? Or this one, maybe near the corner, then, BINGO, he felt a fish give beneath his paws. The latch released, and as Cecil leaped back to the floor, the lid snapped open.

The sailor gave a shout. “I’ll be shivered,” said the first mate. “Did you see that? Black, you’ve got more than luck on your side. I’m thinking you’ve got brains.”

Cecil could see the men were excited, but he had no interest in the chest. It had no scent of Anton. As they pulled the lid open and stood looking wide-eyed at the contents, Cecil hurried off down the hallway.

He passed a bedchamber and stopped to look in. This one contained a larger bed as well as a smaller one to fit a tiny human. There were several tall pieces of furniture, with drawers on the front and bottles and containers lined up on top. Cecil didn’t want to try to jump up on one of them blindly, but he saw a box standing on end in a corner that would give him a better view. He sprang up on the box, turning to catch his balance as it wobbled unsteadily under his weight. As he faced the room again he saw a flash of movement at the far wall. He snapped his head and focused his eyes—it was a cat! His heart pounded crazily in his chest. One, two, three seconds passed before he recognized the feline, but it was not Anton. It was Cecil himself, his furry black reflection staring back at him in a “meer” like the one he had seen on the ship with Gretchen. The glass was attached to the wall across the room, and Cecil saw that he looked just as bad as he felt. He sat back slowly and began to breathe again, closing his eyes and dropping his head as disappointment poured over him in a great wave. It sure smelled like his brother in here, but he was nowhere in sight.

Maybe Anton was here, but he left with the others, Cecil thought. Maybe I’ll have to find out what happened to them. He swallowed with difficulty. This could not be the end of his search—it would not be. He opened his eyes to try to clear his head and focus his thoughts, and was surprised to see a tiny flicker of light somewhere beneath him. It was strange, like a reflection in water, pale green and still. He shuffled his paws back and lowered his head, squinting down. There were narrow slats in the box, and it seemed like the glint of light was coming from inside, down near the bottom. Cecil lay one eye directly on the space between the slats and peered in, and the pale green light blinked.

It was a green eye, looking up at him.

In an instant Cecil had bounded to the floor and dashed around to the open back of the crate. He stood with his legs wide apart to steady himself, gulping in air and laughing. “Hey!” he managed to gasp out, his eyes bright with tears. “Where have you been, little kit?”

Anton lay in the crate, his chest rising and falling, gazing intently at Cecil. “Wanted to see what it is they sing about,” he whispered, smiling. He tried to get to his feet but slumped back into the cushion. Cecil realized with another shock how thin and frail Anton was. He stepped closer and touched Anton’s nose quickly with his own, breathing in the familiar scent of his brother.

“Mother sent me to find you,” Cecil said. “I promised her I would.”

Hieronymus crept slowly out from between Anton’s paws and tried to fix his eyes on the large cat looming above him. Cecil wiped his face with his paw and looked down at the mouse.

“What’s this? A little snack,” he said. He popped out his claws.

Anton held up a paw feebly. “That snack is a friend of mine. He saved my life.”

“It’s true,” Hieronymus squeaked up at Cecil. “If not for me, he would have been a goner.” Hastily, he retreated behind Anton.

Cecil looked back at Anton and nodded. How had a mouse saved his poor brother? It was a story he would want to hear. “Any friend of yours is a friend of mine,” he said.

From down the hallway, they heard the shouts of the pirates: “Huzzah!” and “It’s gold, it’s pure gold,” and then the stamping of boots going from door to door, the first mate shouting, “Lucky Black, where are you, lad? You’re the hero of the day.”

“He’s a kindly one,” Cecil said to Anton. “He actually saved me from drowning. We’ve got to get him to take you off with us.”

Anton sat up, staggered out of the box, and sat down again. Cecil licked his brother’s cheeks and forehead. “You’ve been too sick to clean yourself,” he said.

The first mate looked in the door, and seeing the two cats (but not the mouse hiding behind the pillow), called out to his fellow pirates, who came ambling joyfully behind him, “Here’s our hero, and he’s found a poor abandoned chum.” Cecil mewed and rushed to his boots, then back to Anton—lick, lick, can’t you see he’s my brother?—then back to the boots, meow, meow, meeeooow!

The first mate laughed. “I hear you, Black,” he said. “We’ll take your friend. The gold in that chest is heavy, but he don’t appear to weigh much, so we’ll squeeze him in.” And with that the mate picked Anton up by his scruff, put him inside his vest, and strode out to the deck, where the pirates, having thrown down a rope ladder to the dinghy, were busily loading the sacks of gold doubloons they’d found in the chest. Cecil clambered down with a little help from the crewmen. No one saw the mouse who ran down a line at the stern and bolted under the seat, where he found, to his delight, an old sea biscuit, which he munched on joyfully all the way to the ship.

From a corner of the cage, Gretchen watched the two brothers squabble over the plan. Hero today, gone tomorrow, she thought. The pirates’ gratitude for the gold, like everything else about them, had proved fitful and unreliable. That first night they’d been so overjoyed, the cook had broken out three tins of the oily little fish and presented them in three separate pans. Hieronymus—that mouse!—insisted that Anton hide a few of his under the stove, as he was too weak to eat them all at once. For a few days, the cats could do no wrong, and every pirate hand was outstretched with a treat, every pirate’s ugly face contorted in something resembling a smile when a cat came into view. Then the time came to divide up the gold, and no pirate was content with his share. Cats were no longer of interest, though they still got the dinner leftovers slapped down in one pan and all the dishwater they could drink. Another week passed and open hostility was running rife in the crew—in the wrong place at the wrong time a cat could get kicked. No sooner had they spotted land than the captain gave an order and the friends found themselves, all three plus that mouse, in a cage in a sprawling animal market on the edge of a bustling port city. Again, thought Gretchen ruefully.

Anton had made a good recovery, though he was never going to be a big, strong, muscle-headed guy like his brother. He was quicker and smarter, Gretchen thought. He was a tough cat, not like a fighter, but like a survivor. Seeing them together again made her heart feel light and happy. The brothers, she called them in her thoughts. The brothers were bickering now. Cecil paced up and down, as much as he could in the narrow space.

“You haven’t been in a ‘markit’ like this before,” he advised Anton pompously. “Gretchen and I have, and we know what to do.”

“But . . .” began Anton.

“The thing to do is,” Cecil continued, “whenever somebody comes by, lie down and act like you’re sick or dying. That way we won’t be traded away. We’ll stay with the pirates. We need to stick together, not to be separated all over the world again.” He stopped pacing and sat down to face them.

Anton tried again. “But, are we sure we really want to stick with the pirates? I mean, they don’t seem overly fond of us—they’re eager to trade us off at the first opportunity. Maybe we could find a better life than that.” He noticed Hieronymus, who was able to slip in and out of the cage easily because of his size, trying to get his attention from the shadows.

“The pirates are fine!” Cecil exclaimed, pacing again. “Lots of food, lots of excitement.”

“Lots of danger,” Gretchen commented quietly, watching Anton. She felt oddly protective of him, something she wasn’t used to feeling about anyone except herself.

Hieronymus sidled up next to Anton’s forepaw, glancing nervously at Cecil before speaking. “I’ve examined the latch. It’s made of wood, a wooden peg slipped through a hole in another peg,” he explained to Anton. “I could try gnawing through it, if you think that might work.” They exchanged a glance, almost a wink.

“Work?” Cecil snorted in Anton’s direction. “No offense to your friend, but that’d take forever.”

“It could,” said Anton, amused.

“It would,” said Hieronymus, “but it seems worth a try anyway.” He turned and slipped through the ragged slats of the cage and made his way around to the latch, where he set to chewing.

The keeper of the market was a short man with long hair braided down his back and necklaces of painted wooden beads stacked on his chest. Brandishing a long stick made of cane, he strode back and forth calling out to potential customers, whacking the stick sharply on the tops of the cages of braying or mewling animals. Gretchen tried to strike up a conversation with a few of the other creatures, but none of them were friendly.

“I can’t get any of these other prisoners to tell me a thing,” she remarked to Cecil. After several hours of languishing in the sweltering stall, Gretchen was finding the routine of dutifully falling into a realistic dead faint whenever a human strolled by tiresome. Hieronymus had worked industriously on the wooden latch while avoiding the keeper, who periodically spotted him and hit the front of the cage with his stick, but the mouse had made little progress.

Leaning toward Cecil, Gretchen lowered her voice. “Are you sure we shouldn’t be trying to find a new home, like Anton said?” she asked him.

“Not if it means getting split up again,” Cecil replied, glancing anxiously at Anton, who was by the door encouraging the mouse’s efforts. Gretchen could see the resolve on Cecil’s face; he wasn’t going to let Anton out of his sight if he could help it. “Nope, we’re a team,” he said. “Three heads are better than one!”

“Four!” squeaked Hieronymus from up front. Cecil rolled his eyes.

Anton was worried about the mouse’s endurance. “You know, my friend,” he said seriously, “you could just . . . go.”

Hieronymus spat out a tiny sliver of wood. “What do you mean, go?” he asked.

“You’re not captive in this cage like we are,” said Anton. “You have a chance to escape, and you should take it. Really, you should get out of here.”

Hieronymus held up one paw. “I’ve pledged my troth; I will not leave a friend in danger.” The mouse gave him such a severe look that Anton retreated a bit, trying to think of something else to say. In the next moment, in the din of the stall, Anton heard a human’s voice. He knew he had heard it before, somewhere, but where? He raised his head to listen.

“Yes, yes, I need a cat, mayhap more than one,” a man was saying to the keeper, looking around at the creatures. “I have rats in my larder like you would not believe, such awful brutes!” Anton couldn’t see his face and he didn’t understand the words, but the voice drew him. Cecil saw the man peering into the cages and murmured to the others to get down, but Anton remained standing at the cage door.

“Anton! Get away from there!” Cecil whispered loudly.

“Just a minute,” said Anton, stretching his neck to get a better look. “I think I know this one somehow.”

“Come on, it could be anybody. It’s too risky.”

The man finally turned toward their cage, and Anton saw the tall, thin build and the puffy white beard, like a cloud passing by. It was Cloudy! Anton’s mind raced. Cloudy, from his first ship, for whom he had killed the fearsome rat, the cook who had treated him so kindly and given him the delicious little fishes. Surely he would remember the little gray cat. Anton leaped up with both paws pressed high on the cage door, meowing as loudly as he could. Cecil rose to tackle Anton if necessary.

“What are you doing?” demanded Cecil. “Don’t call attention to yourself. You’ll be traded for sure!”

“It’s all right!” Anton assured him in between yowls. “He’s a good one. He knows me.” Anton was out of breath, but he kept yowling. “And,” he gasped, turning to Cecil, “he knows where I’m from.”

Cecil and Gretchen stared at Anton for a long moment, absorbing the meaning of this statement, then hurtled themselves to the door, adding their voices to the clamor. Cloudy moved down the row to stand in front of the cage.

“Well, what’s all this?” he asked, bending to look at their faces. “Quite a spirited group, aren’t ye?” He caught sight of Anton and paused, furrowing his brow. “And who is this here? Have I met you before, little one?”

Anton thrust his paw through the slats, and Cloudy gently grasped it. The cook touched the scar where the rat’s teeth had sunk in and took in a sharp breath. He quickly looked to Anton’s throat to confirm the deeper one there, then stepped back and smacked his hand on his forehead. “Bless my beard, it’s Mr. Gray, is it? How the devil did ye end up here?” He blinked from Anton to the others. “Well, no matter, we’ve got to get ye out.”

Cloudy collared the keeper and pointed to the cage. The three cats fell silent, suddenly fearful that only Anton would be chosen, but after haggling with the keeper, Cloudy seemed pleased enough to buy the whole lot. The cats huddled together, and Hieronymus stayed out of sight—tucked into the crook of Anton’s elbow—as Cloudy paid a passing boy to cart the cage out of the market and into the fresh sea air of the docks.

After the group had made their way back to the ship—there she was, the Mary Anne, her figurehead of the two little girls still dancing off the bow—the cats were given a quick meal in the galley. Hieronymus was able to slip safely into a dark corner, where he found plenty of crumbs to nibble. They quickly discovered why Cloudy was in need of aid. Cecil heard the noise first, his ears pivoting.

“Rats,” he said with a mix of disdain and anticipation. “A fair number of them, I believe. In there.” He nodded toward the larder.

“Ugh, rats,” said Anton with a sigh. “I had a tough fight with one.”

Cecil eyed Anton’s scar approvingly. “You won, though, didn’t you?”

Anton smiled. “Yes, brother,” he said. “I was the victor.”

Gretchen stepped up so all three stood side by side, facing the larder. They could hear faint clicking and twitching sounds coming from inside. “I ain’t afraid of no stinkin’ rats,” she said fiercely. Cecil and Anton glanced at her with respect.

Cloudy followed the trio to the larder and opened the door. The cats barged in shoulder to shoulder, and Cecil raised his voice.

“All right, you nauseating lowlifes, your time on this ship is UP.” The clicking sounds ceased completely; he had the rats’ attention. “You know why we’re here, and this will not be a pleasure cruise. We’ll give you ONE CHANCE to save your worthless, revolting skins, but if you stupidly choose to stay, which would not be surprising given the puny size of your brains, then we’re looking forward to what comes next.” He paused, popped out his claws, and dragged them sharply across the wooden floorboard, leaving five distinct lines. Gretchen grinned and nodded slowly. Anton squared his shoulders and passed a paw over his cheeks, smoothing his whiskers.

“Count of three, then your time in this world is DONE,” Cecil thundered, leaning forward. “One . . . two . . .” Simultaneously, the three cats crouched to spring.

There was an explosion in the larder as the rats bounded out of their hiding places, knocking boxes and tins off shelves, careening toward the doorway. Anton stepped aside and counted seven or eight of them as they streaked past. Cecil remained planted in the center of the small room so the rodents had to swerve around him, their claws scraping the floor as they scrambled. In seconds they were gone.

“My,” said Gretchen, wide-eyed and smiling at the brothers. “That went well.”

When the cats returned to the galley they found Cloudy, who had briefly hopped up on the table as the rats rushed past, pouring milk from a tin into a large saucer for them. Anton spotted Hieronymus’s eyes shining from the shadows in the corner, the mouse’s little head nodding with pleasure.

“Wonderful!” Cloudy exclaimed, stroking each of them while they purred over the milk. “Better than I could have hoped for.” He put his hands on his hips and leaned against the table, chuckling. “Mr. Gray, you have made some fine friends, you have. We shall enjoy our voyage now.” He waved a large spoon over his head with a flourish. “Next stop, Lunenburg, Nova Scotia!”

And though our heroes could not understand him, dear reader, we know that this was very good news indeed.

Two kittens hurried up the path to the lighthouse, tumbling and rolling as they went. It was tiring, but Billy had entrusted them with an important message, so they pushed on until they could see Sonya sitting on the brick apron by the back door. She was cleaning her tail with long strokes, and she looked up smiling when she heard them coming. Her kittens were only a few months old and so dear to her, with ears too big for their faces and skinny little tails. They were allowed to go exploring during the daylight hours, and she wondered what had these two in such a rush.

“Mama!” panted the black one, who arrived ahead of his sister. “Billy says to come!” A butterfly in the grass distracted him and he veered off.

“Why?” asked Sonya, as the second kitten, gray-striped, flopped down in a heap.

“Don’t know why,” she puffed. “He says to come now, Mama.” She closed her eyes.

Sonya sighed. Billy had been very kind to her since Anton was taken and Cecil had followed. He helped her keep an eye on the kittens and checked on her often, and he let her know when a tall ship came in to the docks because there was always a chance of news of the brothers. But there had been no news, and it was hard not to lose hope. She left the kittens to rest at the lighthouse and started down the path at a trot. Hopeful was better than hopeless, she reminded herself, her heart aching a bit. She thought about her boys every day, whether a ship came in or not.

A crowd had gathered on the roadbed by the docks and Sonya wove her way toward the front, passing cats and people. She nodded to Mildred, the grandmother of Gretchen, that young white cat who had been taken. Mildred was unfailingly present no matter the weather when a big ship arrived, faithfully waiting for news of any kind, good or bad.

“Billy, what’s going on?” asked Sonya when she found him near the water’s edge. “Why all the fuss?”

Billy turned to her and beamed. “It’s the Mary Anne. She’s come back!” He was trying to contain his excitement and doing a very poor job of it.

“The Mary Anne?” Sonya repeated. “The ship that took Anton?” She felt suddenly light-headed and whipped around to find the ship in the distance. There it was, enormous and heaving in the waves under full sail, the little girls on the figurehead clearly discernible.

Mildred stepped up behind them and looked out as well. “Maybe we’ll see your boy today?” she said softly.

Sonya moved a little nearer to the old cat for strength, her heart hammering in her chest. “We’ve gotten our hopes up before, haven’t we? I’ll believe it when I see it,” she said quietly.

“She’s coming about now,” Billy called out anxiously to the crowd, squinting intently at the ship.

Long seconds slipped by. The people milled about, chatting and pointing, but every cat on the wharf strained silently to see something, any sign of a familiar face on the Mary Anne. The great ship dipped majestically as it drew closer; some of the sailors were high up in the rigging pulling in the sails as others busily traversed the deck. And then, in the stillness that had gathered along the ground among the cats, Sonya heard a stirring sound. It was the long, joyful meow of a single cat, almost a howl, rising and falling. And then others to her right and left joined in, mewing cries of recognition and deep kindred spirit until it was a whole chorus of buoyant voices. Sonya felt her eyes begin to sting and cloud up.

“What is it, Bill?” she asked, her voice quavering. “I can’t see a thing.”

Billy opened his mouth and hesitated. “It’s . . . three, my dear lady,” he replied, almost in a whisper, nodding slowly, his eyes fixed on the ship. “Great cats above, it’s all three.”

Sonya’s breath caught in her throat and she blinked hard to clear her eyes.

Finally she saw them, high up in the prow of the ship, sitting tall and proud, side by side, their heads lifted in the cool breeze, one gray, one white, and one black. What she couldn’t see was a dapper little mouse, who stood boldly between the forepaws of the gray cat, talking nonstop.

As Sonya and Mildred and Billy leaned against one another to keep their knees from buckling, the great ship glided into the dockyard, unhurried, and the exultant song of the cats on the wharf rose to welcome their lost friends, found again and home at last.