The Harbor at Lunenburg

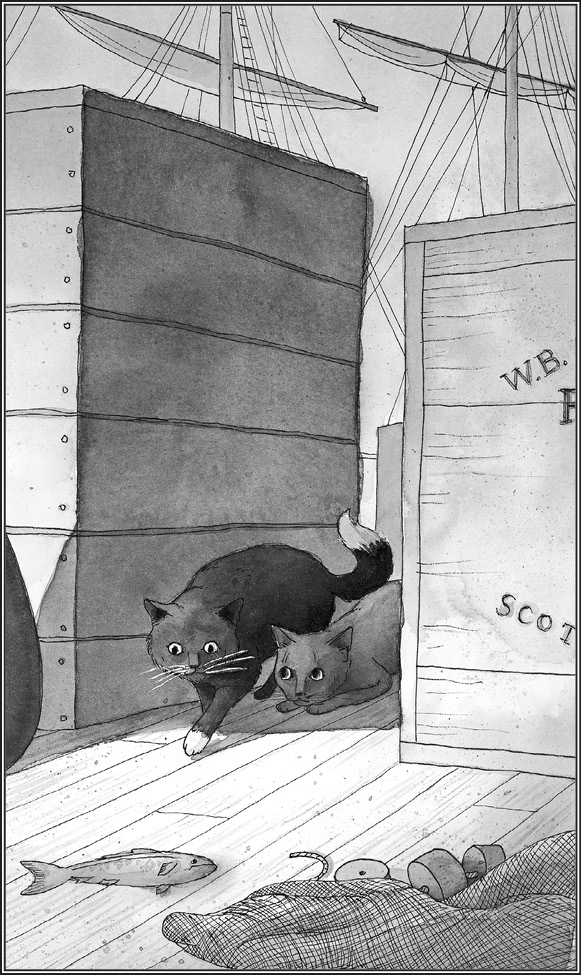

The herring slapped onto the wooden dock as the men shook the nets to free the last of them. Anton and Cecil watched from the shadows between stacks of crates. This was the crucial moment, before the men began scooping the fish into containers and hauling them away. One of the catch, larger than most, flopping helplessly, slithered from the top and careened down the side of the quivering pile of fish. Cecil shifted his weight to his back paws, his muscles tensed.

Anton moved slightly to block him. “Not yet,” he breathed, but Cecil sprang from the crates and in two long bounds reached the fish. He clamped its tail between his jaws and turned sharply, dragging the squirming weight, skidding on the slippery wood. A fisherman grunted and lunged for the fish. He caught its slick gills for a moment before it slid through his fingers. Cecil pulled hard, breaking into a run as the man turned to give chase.

Now Anton darted from the hiding place, eyes wide and intent upon a smaller herring at the bottom of the pile. A fat rubber boot stomped the dock behind him, narrowly missing his tail. He leaped across the pile, scrambling wildly over the churning fish, finally bolting through the closing circle of boots, empty-jawed.

Crouched behind the nearest tower of coiled ropes, Anton listened for pursuers but heard only rough laughter as the men returned to the catch. He trotted along a dirt path lined with scrub weeds, arriving at an old lighthouse perched on the edge of a jumble of flat rocks overlooking the ocean. Slipping between two loose boards on the lighthouse’s foundation, he let his eyes adjust to the dim light inside, carefully stepped around the weathered wooden posts, and stopped, looking at Cecil.

Cecil glanced up, motionless, then returned to cleaning his back paw. The herring lay stiff on the dry stone at his side. “So,” he said, his voice slightly mocking, “where’s yours?”

Anton crouched on the rock slab and folded his tail neatly alongside him. “Hmph,” he snorted. “After the scene you made, there wasn’t much chance for me to get one, was there? So much for sneaking. Next time, I go first!” He lowered his eyelids as if he were bored.

Cecil finished cleaning his paw and turned to his catch, chuckling. “If you’d gone first we’d still be waiting for you to choose one.” With his sharp teeth and claws, he ripped a chunk of flesh from the fish and tossed it to his brother. Anton sniffed the fish carefully, then began to chew small mouthfuls. “It’s like I always tell you, little kit,” said Cecil, his cheeks bursting with herring. “Don’t be a chicken, be a cat! Be adventurous!”

Anton scooped up the last morsel and rose to leave. “Thanks for lunch,” he called as he slipped back out between the boards. But not for the advice, he thought, narrowing his eyes. Cecil was good at many things—hunting and stealing and muscling his way through. But every cat couldn’t be like Cecil. And every cat didn’t need to hear about it.

As Anton rounded the bend in the lighthouse path, he looked out upon the busy port of his home village. The harbor, full of stately tall ships resting at anchor, resembled a forest of leafless trees. Ships with masts as tall as houses, their spars stretching like arms out past the massive hulls, bobbed at anchor as far as the eye could see. The big brigs and three-masted barques in which humans sailed the world plowed toward the docks from the open sea, slow and ponderous as elephants, while the smaller fishing schooners, quick as rabbits, darted into the harbor at dawn, returning in the evening loaded down with hills of shivering silver fish, lobsters as big as platters, nets heaped with oysters, mussels, and clams. The brightly painted shops and houses of the town, built in tiers on a steep slope, looked down upon the waterfront like an audience eager to see a show. And what a show it was, from dawn to dusk.

When the tall ships sailed into the harbor, past the breakwater and up to the docks, many interesting things were disgorged. First came the sailors, intriguing in their own right, with their colorful scarves and sashes and boisterous manners. Then they unloaded the ship’s deep hold. Out came great sacks of flour, metal pipes, wooden carriage wheels, crates of miniature trees with odd-shaped leaves, cows, goats, and sheep, roped together, balking at the gangway, mooing and bleating. There were wooden barrels of all sizes, pallets laden with bales of cotton and wool, skids of bricks and lumber, cages of chickens, huge blocks of ice.

All of it was in constant motion, pushed and pulled by the bustling stevedores who plied their barrows and carts through the ranks of horse-drawn carriages on the docks, past the shouting sailors and the occasional bevy of weeping ladies there to welcome their husbands and their sons. A ceaseless chorus of noise accompanied the mayhem: shouting men, rollicking children, the joyful barking of aimless dogs, the cries of the seagulls rising in squads to circle the town or dive into the harbor, the screech of osprey, the yowling of the town’s resident cats.

Some of the sailors scoffed at the cats, while others gave them a kind word, or even tossed a fish too small or too bony for their own uses. The sailors were not surprised to see the cats, nor were the cats perturbed by the sailors, though they were wary of them, for good reason. But where there are sailors and ships and the sea, there are fish and mice and rats, and where there are fish and mice and rats, there are cats. It has always been so. Humans long to cross the sea, to visit strange lands and see wonders undreamed of. Cats—well, most cats—do not.

Anton and Cecil were brothers born in a cozy recess beneath the old lighthouse perched on the rocky breakwater that curves out from the harbor. Their mother, Sonya, was young when her sons were born; they were her first litter. Like her, Anton was svelte, elegant, and gray as a storm cloud. He was cautious and sensitive by nature, and picky about food. He liked to plan ahead.

Cecil was black with white forepaws, a paintbrush of white at the end of his tail, and startling white whiskers (their father was a stylish tuxedo cat from the town). He was big, beefy, goofy, and omnivorous. Cecil was curious about everything, but especially about ships and the sea. The sailors never saw enough of Anton to give him a name, but Cecil, who liked to sit on the dock in the sun, gazing at the sea like a pensive jack of spades, they called “Blackjack.”

As kittens the brothers were of a size, but Cecil had big paws and his fur was longer and silkier than Anton’s gray coat, which took no time at all for Sonya to clean. Cecil grew taller and heavier, outstripping his brother and then his mother, and then every other cat on the wharf. He was always hungry, and there was nothing he wouldn’t eat. Often a river of mice streamed from the ships looking for new haunts after their journey. Cecil devoured any he could manage to pounce on, even if they made his belly ache for hours afterward. Anton was nimble enough to trap mice in his paws, to let them go and trap them again, but he did it for sport. He simply had no taste for mice. Another treat Cecil enjoyed, to his fastidious brother’s horror, was water beetles.

“They’re good,” Cecil claimed. “They’re crunchy.”

“Ugh,” said Anton. “I’d rather wait for a fish.”

Sonya was a loving mother, and having only two sons meant she had more time to teach them everything she knew about life in the lighthouse, in the town, and on the wharf. The brothers were both fascinated by the bustle of sailors on the waterfront, but Sonya warned them of the dangers of being impressed into service on a ship. “They come on the dock at night, and if they see a cat, they tempt him with fish and then scoop him up and throw him in the hold until the ship is out to sea. Some are never seen again. I knew an old fellow who came back and said he’d seen the world.”

“And what did he see?” asked Cecil.

“Horrible sights. Humans had fur and swung in trees.”

“Frightening,” Anton agreed.

“Interesting,” said Cecil, wide-eyed. “I’d like to see that.”

“And he’d seen a country made of nothing but sand.”

“Flat or hilly?” asked Cecil.

“Who cares?” said Anton. “Right here is the best place in the world for a cat to live. Everybody says that.”

“That’s true,” agreed Sonya. “Everyone says that. Even those who have gone away and come back again.”

During the day, Anton, the more thoughtful brother, preferred to spend his nap times close to Sonya in the lighthouse, snuggled on the old quilt where he’d been born. In the evenings, though, the music from the saloon in town drew him out of hiding to slip quietly through the chill alleys, following the trail of marvelous sounds. He’d found a broken board in the wall of the saloon storeroom, with just enough space to squeeze through. The door into the bar was usually left ajar, and he discovered that he could sit behind it and hear the instruments and the singing well enough. Closing his eyes and curling his paws, he often purred loudly with pleasure as the music rumbled in his rib cage.

One evening, Anton said to Cecil, “You could come with me tonight to hear some music,” but Cecil smiled and shook his head.

“Nope, I’ve got more exciting things to do,” he said as he stalked off, disappearing into the dark. Anton shivered looking after him, hardly daring to think of the mischief he might be up to.

While Anton was out salooning, Cecil climbed the dusty wooden stairs to the top of the lighthouse and sat by the railing, gazing out at the ocean. The bitterly cold wind blew his fur and stung his eyes, but he was content to stay there for hours, smelling the scents of the sea, watching the waves. Sometimes he could see the sails of tall ships moving slowly, mysteriously along the horizon. Tonight, the moon was bright, and he glimpsed a pod of whales playing far from shore. He watched until they faded silently from his view.

A white cat, pale and ghostly in the moonlight, sat on a low wharf near the shore looking down at the silvery shapes in the water. Black fur masked her eyes and ears, a petite thief in the dark night. The high tide pooled within a ring of rocks, presenting a deep bowl of darting fish, quite catchable in her estimation, though admittedly she was young and optimistic in these matters. She crouched low and stretched one pearly paw slowly over the water, extending her claws, cocking her head in an effort to track the path of the swirling fish. A steady breeze off the harbor rustled the leaves in the scrub bushes, waves lapped up on the rocky shoreline, and wooden dock planks creaked and sighed behind her.

She focused on the fish, so near, and tensed for the strike. A wisp of a scent passed under her nose—it seemed out of place. Was it . . . rubber? She twisted sharply around in time to glimpse a short, grubby sailor throw something through the air toward her. She sprang away from him with a shriek, but too late; the fish net landed heavily over her. Rising up on hind legs she struggled, tearing at the netting with her teeth and claws as the sailor rushed to her. A small hole opened in the mesh, big enough to jam a paw through, but the sailor swiftly gathered the edges and scooped her up, grinning through yellowed teeth as he held the net bag high enough to peer at her.

The trapped cat howled frantically as she swung in the netting alongside the sailor’s heavy boots. Whistling a tune as though pleased with himself, the sailor walked down the length of the dock and up a gangway toward a waiting ship. The cat scrambled desperately to right herself in the net, pivoting around her paw, which was still awkwardly thrust through the netting. She shifted her weight to her hindquarters, pushed her free foreleg out as far as it would go, and slashed at the sailor’s leg. The sailor yelped and cursed as her claws ripped through his dungarees into the skin below. Instead of dropping the net as she had hoped, however, he thumped it savagely against a railing, leaving her dazed and mewling in pain and anger.

Up on deck the sailor approached a wide hatchway. The cat heard the click and whine of a door unlatched and opened. The fish net was loosened, her ghost-white body dumped onto a dusty floor. The door slammed shut, then blackness. Silence.