Brother Cats

The sailors who frequented the saloon had a favorite song, and it was Anton’s favorite as well. It had a refrain he waited for, his ears alert, his eyes unblinking, as he gazed through the smoke from his place behind the door. He recognized the words without knowing their meaning. He could run them through his head and pick them out sometimes in the speech of the men on the wharf: “Windy weather boys, stormy weather boys.” And then followed by “When the wind blows, we’re all together boys.” Anton, crouched in his corner, felt his fur lift along his spine.

One chilly night, as the crowd took up this refrain, Anton was so enraptured that he peeked out from his hiding place. He wanted to be part of the music, and he looked at the people in the room for something that might explain to him why he was so drawn to it. How curious these faces were. Why were their noses the same color as their faces? Why was all the fur attached at either end of the head or, in some cases, only one end? Their movements were clumsy, and they made a lot of noise everywhere they went; they could be dangerous, as Sonya had warned, but this singing together brought out something that made Anton feel bold. Unthinking, he stuck his head out a little farther. He could see the singer and a man playing an instrument that whined like a tuneful wind.

Just then the barman shoved the door aside, knocking Anton flat on his back, but only for a moment. Anton surged up, gathering his feet beneath him for a leap past the grumbling man to the top of a barrel. Worse luck, it was the barrel the barman was after and the sight of Anton balanced precariously upon it made him shout.

“Out!” he commanded, waving his hand toward the bar. “Out with you, you sneaking creature.”

Anton dived from the barrel, scrambling across the floor into the bar. Two men leaning against the high counter gave a shout of delight as he cleared the edge in one powerful jump. The wood was slippery and Anton skidded against the rail, but as the men made encouraging comments, he recovered his footing and leaped into the bustling room. The women laughed, the men taunted with what they thought were cat sounds. The barman came out and shouted something that made everyone laugh. Anton could see the door just ahead, but it was closed tight against the chill night. Boots were everywhere between him and his destination, and hands reached out to catch him, but he eluded them. The thought that he might be touched by these giant, rough, loud creatures made his throat feel tight. His eyes darted this way and that, and his ears rotated front to back, listening for a sound that would lead him to safety.

And then he heard it, the thudding of boots approaching the door, the squeak of the hinges with a blast of icy air, as two new patrons came bustling inside, eager to get out of the cold. Anton recognized one of them, a young man wearing a bright bandana around his head, a singer with a voice like a summer breeze. Anton regretted that he couldn’t stay to listen as he made a dash for the four boots, spotted an opening between an unmatched pair, and shot out into the dark night.

Anton kept running until he made the last turn to the lighthouse path. His brother was there, poking among the rocks near the shore, looking for something to eat. Cecil thrust his paws down between two jagged stones. Anton, wanting to appear casual and calm, slowed to a trot. He approached his brother’s tail, which was all he could see of him, waving gaily in the air. “Did you catch something?” he asked.

Cecil’s head came up. A small bluish creature struggled between his powerful jaws. “Crab,” he said through the helplessly flailing claws.

“Yum,” said Anton, who hadn’t eaten since morning.

Cecil flung the crab across the rocks, where it landed at his brother’s front paws. “You can have him,” he said. “My sailors gave me so much fish today, I’m stuffed.”

Anton pawed the crab and sunk his teeth into the still soft shell. My sailors? he thought. “Thanks,” he said.

“Did you see the big ship that came in this morning? It has four masts. Billy called it a barque. You can hardly get across the dock for all the crates they took off it. All my sailors were gathered round it like it was a wonder of the world.”

Anton pulled off a claw with his teeth and swallowed it whole. “Didn’t see it,” he mumbled. “I was sleeping.”

“It’s no way to live the way you’re living, brother,” Cecil cautioned. “You’re in the pub all night and you sleep all day. You’re not eating. You’ll lose your edge and won’t be able to catch your dinner.”

Anton finished off the crab and sat licking his whiskers clean. There was no point in arguing with Cecil when he was in his know-it-all mood, but Anton couldn’t resist. “A cat who is stuffed with fish all day by sailors can’t be called much more than a pet.”

“What can I do?” Cecil replied. “I’m not going to turn down a nice piece of mackerel. That would be crazy.”

Anton gazed out over the dark water. “Are there any more of these crabs?”

“There’s a bunch of them. They’re having a party in the rocks.”

Anton smiled at the idea of a crab party. “I think I’ll go spoil the fun,” he said. He stretched his legs and arched his back, limbering up for the sport.

“I’m not a pet,” Cecil said.

“They call you by a name,” Anton replied. “You’ll end up as fat as old Billy at the harbormaster’s office; they call him Fletcher. His stomach swings like a bag of clamshells.”

“I’m not a pet, I’m a sailor.”

“What do they call you?”

“Blackie. Blackjack. Sometimes Lucky Black.”

“What does it mean?”

“I have no idea.”

Anton raised a paw and extended his claws, then picked at a clot of something between his toes.

“Don’t you want to come see the barque?” Cecil asked.

“You know Mother has warned us about those ships. They don’t come sailing back every day like the schooners. They go out for months on end. Some never come back again. Promise me you won’t go hanging around and get impressed on one of those things.”

“They won’t be taking cats tonight; they just got here.”

“I’m still hungry,” Anton said.

“I’ll wait for you. It’s bigger than a building. It has at least a thousand sails.”

Anton chuckled. “A thousand sails,” he said.

“Well, a hundred.”

“If I go with you to see this ship, will you come listen to the shanties at the saloon? There’s a fine singer coming on later tonight. He’s there every week.”

“It’s full of smoke in those places,” Cecil complained.

“It’s cold on the dock,” Anton countered.

“All right, all right,” Cecil said. “Eat your crabs and we’ll go out for a good time, like two brother sailors.”

Anton rolled his shoulders back, did one last head-to-tail stretch. “Like two brother cats,” he said as he crept out over the rocks.

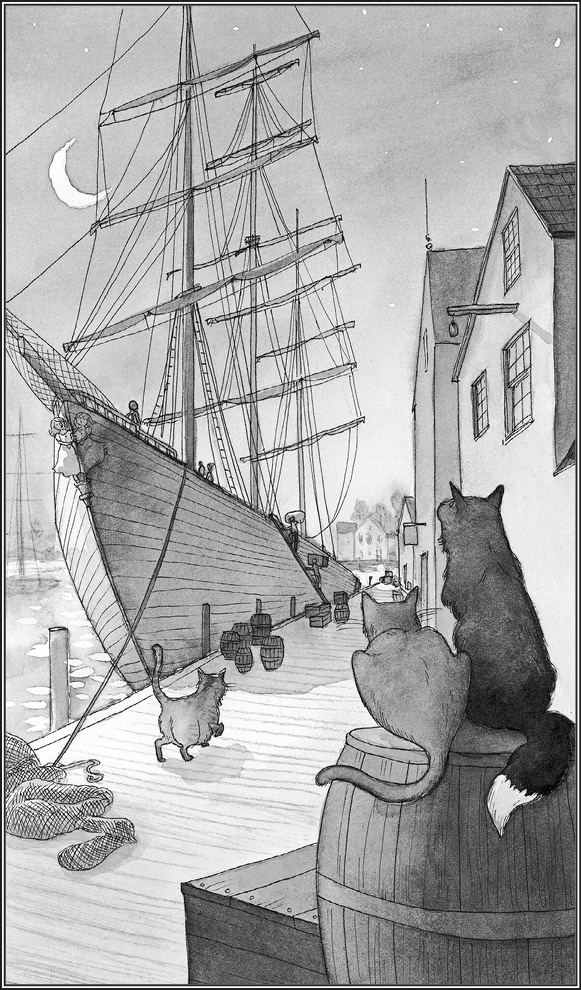

By the time Anton and Cecil got to the dock, the cargo had been largely cleared away. They discovered it was being loaded onto the ship rather than off. “It must have been empty,” Anton observed. “It must be a new ship.”

Billy, the harbormaster’s cat, came shambling up from alongside the gangplank. “Brand-new, she is,” he said, “just out of the yard in Gloucester. She’s called the Mary Anne. You see that figurehead?”

The brothers regarded the brightly painted figure just under the flying bridge. Two young girls in blue dresses with golden hair and golden shoes held hands and seemed to dance on the air. “That’s Mary and Anne, the owner’s daughters,” Billy said. “He’s a shipbuilder himself and this is the biggest vessel ever built on this side.”

“This side of what?” Cecil asked.

“The ocean,” said Billy pompously. “The great sea.”

Cecil bowed his head and allowed the words to flow over him like a wave breaking over a ship’s prow. He thought of the whale, its wondrous eye rolling up from the receding waters to look at him, so wise, so at ease in his element, the sea.

“The ocean,” Anton growled. “Even this great monster of a boat is no match for that.”

“Cats have gone out; a few come back,” said Billy solemnly. “There’s other lands they say, all sorts of wonders.”

“But you’ve never gone?” Cecil asked.

“I never leave this harbor. Why would I? This is the best life a cat can find in all the wide world and across all the seas. Those as come back say it’s so.”

“That’s what Mother says,” Anton agreed.

“Well, she’s right,” said Billy. “Best be off home now. Dangerous out here this time of night, as you boys well know.” He cast them a sidelong look and waddled off, his belly rolling from side to side like a seaman’s hammock in a storm.

Anton looked up at the soaring masts of the big ship, with its crossbars on all four, the square sails rolled up tight and the dark basket of the crow’s nest brooding atop the mizzenmast. Up and down the gangplank the sailors made their way, bandy-legged and crouched beneath the heavy crates and barrels, all bound, he thought, for where? A place like here? Or a land made entirely of sand? Or one where the humans had fur and swung from the trees? Too frightening even to imagine.

“It’s a grand ship,” Cecil said. “When I look at a ship like this, I can’t deny I’d like to see where they go.”

“Don’t think about it,” Anton cautioned. “Come and hear the singing and you’ll never want to leave again.”

Somewhere nearby they heard the snap of a dry twig, or it could have been the crackle of a torch, or the creak of a stacked barrel. Whatever it was, in an instant the brothers vanished, and they didn’t stop running until they reached the town.