Chapter 1 The importance of nursing

1. Discuss the need for nursing and nurses in contemporary Australian and New Zealand society.

2. Explore the part that nurses and nursing play in the healthcare service.

3. Appreciate the limits to the scope of nursing practice.

4. Describe the knowledge, skills and information required for nursing practice.

5. Identify how nurses access and assess required knowledge.

6. Explore the potential advantages of discipline-specific and multidisciplinary perspectives.

7. Recognise how different models of nursing suit organisational, professional and/or patient goals.

8. Outline the means by which nurses account for their standards of practice.

The size and weight of this textbook are a testament to the range and diversity of knowledge that nurses may have in order to nurse, but it does not of itself denote the importance of nursing in society. To understand the importance of nursing it is necessary to look, from a range of perspectives, at what it is that nurses offer to society that is considered valuable. Images of nursing that have been held by various parts of society and in various stages of its history give a glimpse of the importance given to nursing. Figure 1-1 illustrates a range of impressions of nursing roles in society. Nursing is valued in society for a number of attributes. These include: compassionate work—ministering to people who are suffering; body work—dealing intimately with vulnerable bodies; collaborative work—working with doctors, allied healthcare professionals and patients in the provision of a diagnosis, treatment, care and cure of illness; facilitative work—promoting healthy lifestyles to maintain health and following the onset of illness; and technical work—working at the cutting edge of both health science and health engineering. This is extraordinary work done by ordinary people.1,2 The ordinariness of nursing is an asset beyond measure that can endear nurses to the general public and open up possibilities for communication and therapeutic relationships. Acknowledgement of the extraordinariness is also required for nurses to sustain therapeutic modalities and cope with the many stresses encountered in practice.2,3

Figure 1-1 The diversity of nursing—extraordinary work done by ordinary people.

Source: National Library of Australia; BSIP; Australian Associated Press; Photolibrary.

Nursing holds an important and dominant position within the healthcare system and is pivotal to the health outcomes of patients. Contemporary nursing in Australia and New Zealand highlights the role that nurses have in assessing patients and using clinical reasoning to plan appropriate nursing interventions. This chapter provides context to the development and contemporary practice of nursing

The International Council of Nurses’ definition of nursing is given in Box 1-14 and includes the notion of a healthcare service for all people and nursing responses to actual or potential health problems in people. Nursing is essential to every single healthcare service; indeed, nurses form the largest sector of the healthcare workforce. For example, in Australia in 2008 there were 1211 nurses per 100,000 population,5 compared with 341 medical practitioners per 100,000 population.6 In 2008 nursing workplaces/settings were listed as follows by the Australian Institute of Health & Welfare: hospital, psychiatric hospital, outpatient clinic, day procedure centre, residential aged-care centre, hospice, other residential care facility, community health centre, defence force facility, government department, doctors rooms/medical practice, school, commercial/industry/business, tertiary institution and other.5 Wherever nurses work, in primary or tertiary healthcare, they are likely to draw on some of the knowledge about people and the various types of illnesses, therapies and care modalities described and explained in this textbook.

BOX 1-1 International Council of Nurses’ definition of nursing

Nursing encompasses autonomous and multidisciplinary care of individuals of all ages, families, groups and communities, sick or well, and in all settings. Nursing includes the promotion of health, prevention of illness, and the care of ill, disabled and dying people. Advocacy, promotion of a safe environment, research, participation in shaping health policy and in patient and health systems management, and education are also key nursing roles.

Medical–surgical nursing as a term needs some explanation as it is seen by some as an outdated and somewhat medical classification. Historically, the classifications of medicine and surgery derived from the therapies that were offered to people for diseases—either surgical treatment or medical treatment—and to this day the classifications of medicine and surgery are used to describe types of wards and doctors (e.g. physicians or surgeons). In this book, medical–surgical nursing is interpreted in its broadest sense and extends to prevention and primary care, and specialities such as critical care and aged care. The diagnosis, treatment and prevention of a range of physical diseases are important aspects of medical–surgical treatment, and nurses use a systematic approach to the assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation and evaluation of care associated with health problems or potential problems with which patients present. Best practice requires that nurses, doctors and allied healthcare professionals work, learn and research well together to provide state-of-the-art medical and surgical services for all people.

The evolution of nursing as an essential service in Australia and New Zealand

Nursing in Australia and New Zealand shares a history and discipline with nursing throughout the world. The discipline has developed generic theories of nursing, society, health and illness that now form an enormous body of knowledge.

Nursing as it is known and regulated today did not exist in the Indigenous communities of either Australia or New Zealand. Indigenous peoples had their own traditions of caring for the sick and ways of living that supported healthy lives—ways that were dramatically disrupted by colonisation.

Modern nursing as we know it today in both New Zealand and Australia was introduced by the British through the institution of colonial hospitals run by both a master and a matron. While the early matrons were housekeepers, they did oversee nurses and nursing duties. Also, in those days more men were wardsmen than women. The dominant image of nurses during this time is of slovenly women who were predominantly uneducated and rough. This portrayal dramatically changed when Florence Nightingale introduced public health reforms and discipline for nurses, with positive effects on the standards of care and hygiene in hospitals. Lucy Osborn, a British nurse, brought these reforms to Sydney, and Grace Neill brought these changes to New Zealand.7–9

Education was introduced into nursing through Florence Nightingale’s system of vocational training in both New Zealand (Wellington Hospital, 1883) and Australia (Sydney Hospital, 1868). It was a system that promoted nursing as a vocation in which dedication to duty, hard work and obedience was pivotal. Thus began a long tradition of obsequiousness to ‘senior’ nurses and doctors that endures today in the form of healthcare service bureaucracy and hierarchies. The introduction of uniforms, high standards of cleanliness and training for nurses had a positive impact on the image of nursing and it became a popular choice of work for women of all classes.

Medical and surgical technologies have developed rapidly since those early days and particularly in the past half century (e.g. medical imaging, microsurgery and chemotherapies), resulting in more rather than fewer people requiring healthcare services and a concomitant increase in the need for nurses. People in hospital are more acutely ill than they were even 10 years ago; in particular, they are older and more frail with complex and chronic physical and social problems. The number of people who now live with and manage chronic illness has increased and thus changed the role of nurses. The strict delineation between medical and surgical nursing no longer exists because a high proportion of surgical patients will be older persons with associated medical conditions complicating their surgical preparation and recovery. Patients with a chronic illness are predominantly managed at home supported by family and nursing specialists; for example, respiratory nurses offer specialist advice and support to people with asthma and their families. However, although they are of particular importance in rural and remote areas of Australia and New Zealand, such services can be offered only where there is a critical mass of people requiring the services. This poses particular challenges to nurses practising in rural communities, who need to be generalist nurses rather than specialists.

Rural communities have seen a steady decline in local healthcare services as costs have escalated and services have become more technically complex, resulting in some services being concentrated in larger centres. To counterbalance this, nursing has made an effort to focus on community services and primary healthcare in nursing curricula and research; however, the majority of nurses still work in hospitals.5 The days when patients were allowed to stay in hospital to recuperate from a medical procedure with nursing care are long gone, with the possible exception of cancer centres and hospice care for the dying. Instead, people recover in the community supported by partners, family and, when available and necessary, social and nursing services.

A radical change for nursing over the last 20 years has been the move to tertiary education for nurses and the development of postgraduate qualifications in clinical specialties, education and management. As the roles of registered nurses (RNs) have changed over the years and their education has become more sophisticated, nurses now take on more work that was formerly the exclusive role of doctors (e.g. women’s health assessment and Pap smear testing). In turn, nurses recognise that a large amount of what was termed nursing10 is currently provided to people by family carers, by assistants in nursing with varying amounts of formal education and, in Indigenous communities, by Indigenous healthcare workers. Their work is invaluable and professional nurses support the many other people who provide such essential care. The British Royal College of Nursing identifies the points of difference between professional nursing and informal nursing as follows:

• the clinical judgement inherent in the processes of assessment, diagnosis, prescription and evaluation

• the knowledge that is the basis of the assessment of need and the determination of action to meet the need

• the personal accountability for all decisions and actions, including the decision to delegate to others

• the structured relationship between the nurse and the patient, which incorporates professional regulation and a code of ethics within a statutory framework.10

Since 1901 in New Zealand and 1912 in Australia, the profession of nursing and the title ‘nurse’ have been regulated (see Table 1-1) and the only people who are allowed to seek employment as a nurse are registered and enrolled nurses whose education and practice are regulated and whose standards are set by the profession. Linked to this resultant monopoly on the practice of nursing, nurses have inherent professional obligations that stem from the social contract they have with society. This includes the obligation to practice in accordance with the ethical and behavioural standards embedded in the Code of Ethics for Nurses and the Code of Conduct for Nurses in Australia and New Zealand.

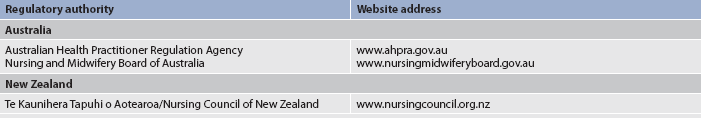

TABLE 1-1 Regulatory authorities in Australia and New Zealand

Note: The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (ANMC) was established in 1992 to help the various nursing and midwifery authorities reach a national approach to standards. In the reformed system of national registration for nursing and midwifery in Australia its principal role is now the accreditation of nursing education programs leading to endorsement or registration. Consistent with its new role the Council has been renamed the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council.

The unique contexts and cultures in Australia and New Zealand make nursing special and different from nursing in other parts of the world. A striking feature of both New Zealand and Australia is the rich cultural heritage of the Indigenous people. Equally striking is the stark contrast between the state of health of the Indigenous population and that of the majority population in each country. The relatively poor state of health of Indigenous peoples is a constant challenge to all healthcare professionals and to society as a whole. Indigenous nurses and healthcare workers make an enormous contribution to healthcare services and are well positioned to spearhead culturally sensitive healthcare programs. These nurses and healthcare workers deserve support and encouragement from non-Indigenous colleagues who strive to understand and respect cultural traditions. Books such as In our own right: Black Australian nurses’ stories graphically bring to life, through storytelling, the experiences, trials, tribulations and triumphs of Indigenous nurses in Australia and provide vital sources of understanding.11

Other hallmarks are the mix of peoples from so many cultures, our relatively small populations, vast and insular landscapes, rural and remote communities, and climates that span the full ambit (from near Antarctic conditions at the lower end of the South Island of New Zealand to the tropical Torres Strait Islands in the far north of Australia). These particular features give Australian and New Zealand nurses a broad range of experiences that make them very adaptable and internationally marketable; they have a sound reputation for their skills, adaptability and friendliness, which means their experience is appreciated and recognised by most countries in the world.

Professional teamwork

From a sociological perspective, nursing is considered a profession, albeit one of the newer ones when compared with traditional professions such as law or medicine. Over the years the role of the nurse has specialised as knowledge has become more specialised, and health has followed the lead of medical science. As a result, a host of healthcare service professions together provide comprehensive diagnosis, care and therapy to patients. For example, in the treatment of a patient following neurological trauma, nurses who work only with people who have had a stroke may attend the patient or prepare the patient for a brain scan and provide reassurance during the procedure, whereas a radiographer who works only on brain scans performs the scan, physiotherapists who specialise in neurological trauma provide rehabilitation, and social workers work through problems with the patient and family. All these people share a great deal of knowledge about people with neurological problems, as well as having knowledge specific to their profession. However, among all the professions that contribute to a stroke team, only nurses are required to attend to the patient’s needs 24 hours a day as well as be multifunctional. Successful teamwork is built on sound communication and mutual respect, neither of which should be underestimated or taken for granted.

AUTONOMOUS PRACTICE, RESPONSIBILITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Nurses may be considered autonomous practitioners but this freedom to make decisions comes with requirements to work within their scope of practice and with respect for the contributions of nursing and other colleagues. Professional responsibility, accountability, authority and delegation are pivotal to professional nursing work. Moreover, in Australia, a significant number of health professions come within the jurisdiction of the Australian Health Professional Regulatory Authority. The Authority requires that practitioners of the particular profession must be licensed to practise and this is achieved by registration. Nursing is one of these regulated professions, so nurses are required to be registered.

The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency has established the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Board, which has responsibility for licensing nurses and maintains a register of all nurses in Australia. Only those nurses whose names appear in the register can lawfully use the title of nurse and practise nursing, and they can do so throughout Australia. In return for this right to call oneself a nurse, to practise nursing and to be remunerated for doing so, a nurse is compelled to practise nursing in compliance with a scope of practice and standards of practice prescribed by the licensing authority. The standards for practice are set out in competency standards for registered nurses and for enrolled nurses. The Board also requires compliance with the Code of Conduct for Nurses in Australia and the Code of Ethics for Nurses in Australia. Both competencies and scope of practice are dealt with more extensively later in this chapter. All of these standards and codes can be found on the website of the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Board (see Resources on p 21). Compliance is not optional and the Board has significant disciplinary powers that it can bring to bear on nurses who fail to achieve the high standards demanded of the professional nurse. The powers extend to the cancellation of registration. This regulatory arrangement can be understood as a social contract between society and nurses, and the overriding concern of the licensing authority is the protection of the public. In both Australia and New Zealand, nursing and midwifery are regarded as separate professions with their own regulations, standards and competencies.

Responsibility

Responsibility for their own work is something that each individual nurse accepts either implicitly (each day they start work) or explicitly (when asked to take on added responsibility). There are two sets of decisions about responsibility. First, the person giving responsibility has to decide whether the person accepting it has the necessary knowledge and skills to discharge the responsibility; and second, the person accepting responsibility should be confident that they have the required knowledge and skills. It is assumed that registered nurses have at least a beginning set of competencies and that they continue to learn, keep up to date and extend their repertoire of skills and knowledge.

Accountability

Once nurses have accepted responsibility for certain work, they are then accountable; that is, they are obliged to disclose what was done, why it was done and the consequences of the action. Nurses are accountable for their work to: patients and their relatives; the profession (through its regulatory authorities); the state, representing society; and the multidisciplinary team, which includes other nurses. This accountability includes nursing documentation but also occurs verbally during patient and family consultations and nursing reports. Verbal accounts do not endure in the same ways as written materials and even though nurses tend to favour oral communication, documentation is important for the purpose of accounting for work and as a legal record of nursing actions and their consequences.

Authority

Authority relates to the formal power to do things. Sometimes nurses are given responsibility for things, such as ordering surgical stores and keeping within budget, but they are not given the power to decide what will be ordered. This lack of authority makes it difficult to discharge the responsibility and account for decisions and actions. Nurses do not have authority to practise beyond their scope of practice, but this is a complex issue, particularly in the case of emergency situations or in rural and remote area nursing where other healthcare professionals are not readily available.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY/INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAMWORK

People presenting with health needs are likely to come in contact with a number of healthcare professionals and, when these professionals work well together, care and treatment are coordinated, efficient and tailored to the individual’s needs. It often falls on nurses to organise and coordinate the care of patients, particularly those with complex needs who have been admitted to hospital. As the earlier example of a stroke team suggested, the interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary healthcare team may comprise medical doctors, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists, dieticians, psychologists, social workers, speech therapists, radiographers, podiatrists and spiritual pastors.

Multidisciplinary teamwork involves a range of professionals working together away from their disciplinary base (e.g. a special project). Interdisciplinary teamwork, however, involves a range of professionals working together towards a collaborative and integrated approach to patient care.12 Good teamwork is essential; however, interdisciplinary teamwork in healthcare can be fraught with tensions, such as interdisciplinary and intradisciplinary rivalry and power struggles, which can negatively affect relationships and communication. A sound philosophy that places the patient or community at the centre of the service can act as a unifying force that requires all parties to make decisions that favour the patient rather than professional interests.

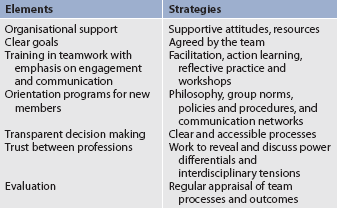

Teamwork needs to be developed and supported systematically and structurally. Integrated learning initiatives in the education of healthcare professionals, at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels, are based on an assumption that learning together will improve understanding and on an appreciation of the contributions from the different healthcare professions. Examples can be found of shared biomedical science classes, communication skills learning and some clinical skills development. Communication and teamwork skills are some of the essential elements of multiprofessional and interprofessional teamwork as illustrated in Table 1-2 and are thus incorporated in contemporary courses.

ROLES, COMPETENCIES AND SCOPE OF PRACTICE

Roles

What nurses do is described in nursing roles. However, nursing roles change and develop as needs in society change and as medical and surgical technology advances. For example, the role of the nurse as caregiver has changed in the community. Formerly, community nurses assisted dependent people with activities of living in their homes, but as the numbers of frail older people living at home increased, nurses needed to spend time on other aspects of care, such as wound dressing or insulin administration. Consequently, assistance with washing and dressing became a role for assistants who, in some cases, come under the direction of social services rather than health. In one study, 38 nurses in a range of roles were interviewed about their work and it was found that there was no such thing as a typical day for a nurse. Nurses were expected to be flexible and adaptable, to expect the unexpected and to deal with an ever-changing environment of people and politics.13 It was concluded that nurses work with a variety of people, face a myriad of challenges and need a contemporary complement of skills for practice. This breadth of practice makes the regulation and control of nursing more complex, but it also serves to highlight the range of areas in which nurses have a role and are deemed important to communities.

Nursing roles differ according to the particular position; for example, a nurse in a well women’s clinic will do different things to a nurse who works in an intensive care unit or a factory. However, even the same position can change dramatically over the years. This variety is one of the many positive things about nursing and means that people with different talents and tastes can all find a niche somewhere. It is quite possible in nursing to change directions several times and to do very different jobs while still remaining within the profession of nursing. Moreover, it is possible to find flexible work that fits with personal life and priorities.

Over the years nursing roles have expanded and extended. Roles have expanded by increasing in breadth; for example, in primary nursing one nurse will provide all the care for a patient from beginning to end of the referral. The reverse of this has happened in the community, however, as nursing roles have been redirected from supporting people with activities of living towards concentrating efforts in more specialised activities. The role of the nurse has extended through the taking on of duties that were previously the role of another profession (e.g. taking blood, inserting intravenous cannulae or assisting with surgical removal of veins prior to cardiac surgery). Changes in roles are exciting and increase the range of nursing services but they do have to be introduced with due regard to education, to ensure efficient and effective delivery of the new practice, and to resources, to ensure that there is time to undertake the new practice. That is, nurses need to become skilled in the procedure and workloads need to be adjusted to include the extra time taken to provide the new skill.

Competencies

Nursing roles should be prepared bearing in mind nursing competencies and scope of practice. It is usual for nurses to be given a probationary period of time during which they acquire the skills and education required to perform all aspects of the role. Additionally, a number of skills are deemed to be essential, for which nurses are regularly assessed (e.g. basic life support).

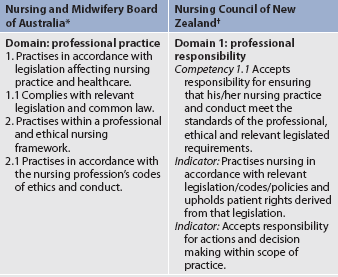

There are written competencies for all levels of nurses in Australia and New Zealand (i.e. enrolled nurses, registered nurses, advanced nurses and nurse practitioners) that prescribe a person’s expected ability to perform as a nurse. Moreover, competencies have been developed for specialist areas of practice; for example, critical care nursing has been developed by the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses, and rural and remote area nurse competencies have been endorsed by the Council of Remote Area Nurses of Australia. The distinction between a skill and a competency is that a competency includes a standard of performance—that is, an indication of the level at which the skill, with associated knowledge and attitude, is to be performed. Table 1-3 gives examples of both Australian and New Zealand competencies and their indicators.

TABLE 1-3 Examples of Australian and New Zealand competencies

* National competency standards for the registered nurse. Available at www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-and-Guidelines.aspx/.

† NCNZ. Competencies for the registered nurse scope of practice. Available at www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/competenciesrn.pdf.

The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council oversaw the development of a Professional Practice Framework for nurses in Australia. Various agencies contributed to this framework. For example, the former Queensland Nursing Council (which ceased to exist in 2010 after the introduction of a national system of registration for health professionals) developed a continuum of practice for nurses (see Fig 1-2).14 This positions the different levels of nurses based on their experience, from unlicensed healthcare workers through to enrolled nurses as beginning practitioners to advanced practitioners and registered nurses as beginning practitioners to advanced practitioners, advanced specialists and nurse practitioners (see Fig 1-3). The Professional Practice Framework is now owned by the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia.

Figure 1-2 Queensland Nursing Council: Scope of practice framework for nurses and midwives.

Source: Queensland Nursing Council (2005).

Before registration, all nurses complete a course of study (bachelor, diploma or certificate) that is accredited by the nursing regulatory authority in the particular jurisdiction. The basis of accreditation is generally that the program provides mechanisms for the achievement of the prescribed competencies. Under the new national system of registration, the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council accredits undergraduate programs of nursing education (see Resources on p 21). The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council highlights that competency assessment relates to performance and assessors make inferences about competence embedded in the person’s practice.15 Therefore, the assessment should not be a one-off event, nor a skills checklist. Nurses are required to maintain their competences and, in Australia and New Zealand, they are required, as they renew their licence to practise, to reflect on their practice and to make a self-declaration about their competence to practise nursing.

Other indicators of continuing competence that may be required are recency of practice and continuing education. For example, in New Zealand nurses are required to have proof of at least 60 days of practice in the preceding 3 years and 60 hours of continuing education; and from 2010, the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia requires all nurses and midwives renewing their registration to meet the continuing professional development standards outlined on its website (see Resources on p 21). Recency of practice is considered to be a reasonable, if somewhat limited, indicator because nowadays nurses are taught to use critical self-reflection from early in their training. To help further they should be given support through processes of performance management and feedback on performance that may be used to determine and declare their competence.

Incompetence, a much rarer phenomenon, is dealt with through line management at work or, in severe cases, the nurse regulatory authorities. Incompetence is identified by self-referral, performance management or complaints from colleagues or clients. The integrity of the profession rests on its ability to account publicly for the continuing competence of nurses and the prompt, fair and effective management of incompetence. This is a responsibility that rests with all nurses, through their support of licence renewal processes, continuing education and reflective practice.

Scope of practice

The term scope of practice has different meanings in the Australian and New Zealand contexts. In Australia, scope of practice is referred to when nurses and employers decide what constitutes the nurse’s duties, and determining the scope of practice is supported by scope of practice frameworks. These are documents that help nurses to understand the implications of accepting responsibility and the factors that should be taken into account. According to the former Queensland Nursing Council, a nurse’s scope of practice ‘is that which nurses and midwives are educated, competent and authorised to perform’. However, the actual scope of practice is influenced by the:

• context in which the nurse or midwife practises

• level of competence, education and qualifications of the individual nurse or midwife

• policies of the healthcare service provider.14

If nursing is responsive to individual, group and community needs for a healthcare service, then it follows that scope of practice will be relatively fluid in order to accommodate the public need for flexibility and diversity in the provision of nursing services. This type of approach to scope of practice shifts responsibility from the regulatory authorities to nurses inasmuch as there is not a prescribed list of things that nurses are allowed to do. In order to gauge their scope of practice nurses are required to know the law regulating and relating to nursing practice and to have a realistic appreciation of their knowledge and skills. There is also the possibility of nurses advancing their scope of practice as they gain experience and education. These possibilities are shown in Figure 1-2. The numerous documents that outline roles, competencies and scope of practice are not merely a paper exercise. They are the way that the profession formally demonstrates to government and the public the serious nature of nursing work and nurses’ endeavours to discharge their duty to the public to provide high standards of nursing care.

In New Zealand, four scopes of practice under regulation by the Nursing Council of New Zealand are legislated by the Health Practitioners’ Competency Assurance Act (2003). The four scopes of practice are: registered nurse, nurse practitioner, nurse assistant and enrolled nurse. Each of these scopes has its own set of competencies and qualifications. The Nursing Council’s competencies describe the skills, knowledge and activities of each scope of practice. In addition to the regulated scopes of practice, nurses who were registered some years ago in New Zealand may have specific conditions on their registration (e.g. only practise in general and obstetric nursing, or only in mental health nursing). Nurses qualifying from 3-year bachelor’s programs today have no such conditions placed on their practice.

THE ORGANISATION OF NURSING WORK

A term commonly used to explain the organisation of nursing work in its broadest meaning is model of care. Nursing models have been used for the last 20 years as terms for conceptual models of nursing theory. A model of care includes the philosophy of the nursing (or, increasingly, the interdisciplinary) team, the profile of the workforce and the systems of work organisation and governance employed to deliver care and therapy to patients and their family or friends.

Philosophies or mission statements are written accounts of the values and beliefs that underpin practice in particular areas. When produced by a team working together, they serve as testament to the commitment of the team to work in agreed ways that will enable the expression of their values and beliefs. As idealistic statements they do not represent reality but they do help the team members to see what they would like to achieve and what behaviours can be expected of other team members. These statements in turn enable the team to decide how to organise teamwork (i.e. they serve as reference points). For example, a team that believes in patient-focused care will endeavour to organise nursing work around the needs of the patient rather than the needs of the nurses.

The profile of the workforce refers to the number and type of healthcare professionals involved and their knowledge and experience in the specialty. For example, in a nursing team where the majority of the team are newly qualified the level of supervision required will be greater. In an all-experienced registered nurse team it will be possible to allocate patients to the nurses with little supervision. The clinical leader of the team is responsible for working with the team to clarify values and beliefs and to organise working routines that facilitate high standards of healthcare. If the multiprofessional team is unable to agree on values and work towards common goals, the possibility of fragmentation and duplication of care occurs.

Task allocation, patient allocation, team nursing and primary nursing are the most common ways of organising nursing work in hospital units. There are, however, many different interpretations of these systems and considerable overlap; for example, primary nursing with team nursing is very successful.

Task allocation

Although outdated in the literature, task allocation is still alive and well. This is particularly so in units that have a low skill mix. In task allocation, the most junior and least skilled people undertake the tasks with patients that are considered not to need high levels of nursing knowledge and skill. For example, assistants in nursing may help mobile patients to shower and dress. Registered nurses may be the ones who give cancer patients their chemotherapy drugs, whereas the most senior nurse on duty might be the one who gives information to relatives and friends and takes doctors’ orders. Task allocation is an effective and efficient way of working and, in principle, is like an assembly line in a factory. The disadvantage is that it fragments care and detracts from holistic understanding of the patient. The potential is there for the patient to be interrupted all day long by a line of different nurses doing their ‘thing’. Patients and relatives get little chance to express their feelings and/or needs to anyone who can or will do anything about them.

Patient allocation

Another method of organising nursing work is patient allocation. With this method, the report is taken from one shift and the senior nurse for the new shift assigns nurses to patients. The decision regarding patient allocation usually depends on matching experience, knowledge and skills with the physical condition of the patient (see Fig 1-4). Other considerations may be who looked after which patient the day before—on a ward that values continuity of care a nurse will be allocated the same patients if possible. The nurse carries out all aspects of care for the patient while on duty, updates the care plan and hands over to the next nurse on duty. This system has the potential for the nurse to include the patient in decision making about the planning of the day and ensures that an overall evaluation of progress can be made. However, it also tends to break up the nursing team. Nurses get engrossed in their care with their patients and sometimes less experienced nurses are left to work with their patients without guidance from more experienced nurses. Although this system allows for continuity during the day, unless the nurse is allocated to the patient each day it does not support continuity of care over the duration of the patient’s stay in hospital.

Team nursing

Patients in a unit or ward are assigned to a team of nurses who will together provide 24-hour care for them while in hospital. Hopefully on any one shift there will be a more experienced nurse from the team who will be able to supervise and work with the other nurse/s. The allocation of work within the team depends on the particular situation. Task or patient allocation can be used within a team structure or, indeed, primary nursing may also be used. Team nursing gives nurses support while on a shift. Because the number of patients that nurses are likely to look after in the course of a number of days is reduced, there is also more opportunity to get to know patients and establish therapeutic relationships.

Primary nursing

Primary nursing was first described in the 1980s as a professional system of nursing care.16 The registered nurse as a ‘primary nurse’ accepts responsibility for the care of a patient from admission to discharge. Whenever on duty the primary nurse is the person to deliver direct care to the patient and make contact with the patient’s relatives. When the nurse is not on duty, the nurse leaves a prescription of care in the form of a care plan that another nurse, called the associate nurse, will carry out on the primary nurse’s behalf. If there is a change in the patient’s condition, the associate nurse will change the care plan and account for the change to the primary nurse. Registered nurses have varying numbers of primary patients and they may, on a shift, also take on an associate nurse role and care for another primary nurse’s patients. This system of nursing allows for the development of a therapeutic relationship between the nurse and the patient, provides for excellent continuity of care, affords opportunities for good communication between relatives and professionals, and reduces the likelihood of fragmentation of care. However, it is difficult to maintain equity of workloads without shifting nurses and patients, so unless it is introduced with team nursing it can fracture the nursing team and isolate nurses and patients.

Case management

Case management has been adopted in community mental health in Australia and New Zealand and in American hospitals. One person takes responsibility for the coordination of a patient’s care. This person is not necessarily a nurse and may or may not deliver direct care. The coordination streamlines care and ensures that referrals are timely and discharge is planned. However, it can be rather standardised and unsympathetic to the personal circumstances of individual patients.

Nursing knowledge

Much of the early intellectual work in nursing revolved around the definition of nursing for the simple reason that unless nurses can define their practice others will do it for them and it is assumed they will have no control over what they do, learn, research or become. Most of this theoretical work has been and still is done in the US, where nursing has been in the university system for much longer than in either New Zealand or Australia; a notable exception is Judith Christensen, a New Zealand nursing theorist.17 Nursing theorists develop theories of nursing with the express purpose of enabling the profession to have a distinctive disciplinary focus—something that distinguishes nursing from other healthcare professions and guides practice, policy, learning and research.

Jacqueline Fawcett proposes four concepts that form the organising structure or orientation of nursing: people, environment, health and nursing.18 Box 1-2 shows how these concepts are used to create four related statements that convey the focus of the nursing role through a range of activities.18 This work has been through several iterations as academics have debated the nature of a grand theory for the discipline of nursing. This is a dynamic process and will continue to develop. There are more simple ways of defining nursing (e.g. ‘nursing is what nurses do’) but as nursing is not simple, such statements have been criticised as being of little use if they do not address the specifics of nursing.

The discipline of nursing is concerned with the:

1. principles and laws that govern human processes of living and dying

2. patterning of human health experiences within the context of the environment

3. nursing actions or processes that are beneficial to people

4. human processes of living and dying, recognising that people are in a continuous relationship with their environment.

Source: Fawcett J. Contemporary nursing knowledge: analysis and evaluation of nursing models and theories. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 2005.

The International Council of Nurses states that it is up to each country to determine and define nursing practice in context. In response to this, the British Royal College of Nursing undertook to define nursing after consulting with nurses.10 As a result it was concluded that for a definition to be comprehensive and in order to distinguish nursing from other healthcare professions, it must include the purpose of nursing, how this purpose is achieved and the particular domain that is identified by its discipline-specific knowledge base. The British definition of nursing is, admittedly and unashamedly, a practical rather than a theoretical one as it was developed primarily through a process of consultation with nurses, in direct contrast to the intellectual process and debate that has contributed to Fawcett’s theory.

The British Royal College of Nursing’s consultation with nurses also found that British nurses have difficulty identifying what specifically is nursing knowledge. As a result they determined the following possible explanations for this: nurses are not used to articulating their knowledge; nurses do not have the right language to express their knowledge; or nurses are unaware of the knowledge they have.10 Nursing languages and conceptual models of nursing have been developed expressly to provide these answers. However, it may be that the nurses who had this difficulty are merely expressing the reality of contemporary practice, where advances in technologies and access to information for everyone are blurring disciplinary boundaries and it really is becoming harder to decide what is exclusively nursing.

NURSING LANGUAGES

Work that has mainly been conducted in North America has moved towards standardising nursing languages. Standardised nursing languages are used to define and evaluate nursing care clearly. Instead of using a wide variety of words and methods to describe the same patient problems and nursing care, a readily understood common language can improve communication among nurses,19 thus promoting continuity of patient care and providing data that can support the credibility of the profession. Standardised languages help identify the most effective nursing interventions as well. Do the patient problems of pressure ulcer, decubitus ulcer and skin breakdown all mean the same thing? Does turning the patient every 2 hours mean the same as repositioning the patient every 2 hours? And if the patient is turned or repositioned every 2 hours, what happens as a result? How are the results described? If a patient was placed on an air mattress, were the results different from those for one who was placed on a standard mattress? How do nurses know what works best? By using standardised languages, nurses can uniformly collect and analyse nursing data to identify the effectiveness of nursing interventions.

Standardised languages (nomenclatures, classification systems, taxonomies) offer ways to organise and describe nursing phenomena. Although philosophical debates exist about whether nursing needs one or more taxonomies considering the complexity of healthcare delivery, a number of classification systems are being developed. The variety of languages that have been developed address different areas of nursing and details of terminology and data element sets are listed by the American Nurses Association (see Resources on p 21). The Omaha System and the Home Health Care Classification have been developed for long-term and home healthcare nursing. The Perioperative Nursing Dataset (see Ch 18) is used by perioperative nurses. The Nursing Management Minimum Data Set is available for use by nurse managers and administrators.

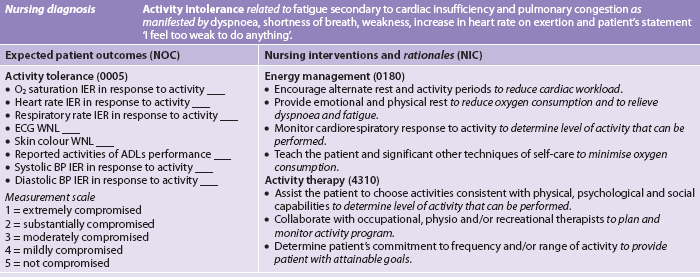

Three of the nursing languages recognised by the American Nurses Association are now available to describe patient responses, nursing interventions and patient outcomes consistently. These include the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association’s (NANDA) Nursing Diagnoses: Definitions and Classification; Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC); and Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC). Each of these classification systems focuses on one component of the nursing process. Patients’ responses or problems can be labelled using the nursing diagnoses classified and defined by NANDA.20 Nursing interventions, or treatments, can be selected and implemented from the NIC.21 Patient outcomes of nursing care can be identified and evaluated by selecting appropriate NOC outcomes and indicators.22 The use of these three classification systems in the nursing process and documentation are further described in this chapter and used throughout the book.

In Australia and New Zealand, however, no universally accepted or officially recognised standardised nursing language has been adopted and, therefore, when using standardised languages nursing students are referred to the American classifications. While the practical nature of the classification systems is recognised, it has been noted that the creation of nursing languages opens nursing up to critique and has separated nursing from medicine and from patients, who could be reduced to objects of nursing diagnoses and treatments, which opposes the nursing understanding of viewing the patient holistically.23

CONCEPTUAL MODELS OF NURSING

A model of nursing is a representation of the real situation, serving to make nursing accessible and open to study as a whole. Conceptual models consist of abstract concepts that together link to form a frame of reference for nursing. These conceptual models of nursing are useful in a range of ways—they can form the framework for health assessments, therapies, evaluations, therapeutic relationships, curricula, research and healthcare services. Furthermore, they commonly refer to nursing as a generic service rather than discrete specialisms; for example, it has been contended that ‘self-care theory’ is pertinent to all areas of nursing, from primary nursing to aged care.24 Interpretations of the original theories of nursing practice models have been related to planning care and nursing decisions, with an emphasis on the practical nature of conceptual models.25

However, in Australia and New Zealand conceptual models have been rejected by practising nurses to a large extent, even though they do underpin and give direction to nursing curricula and are therefore studied in schools of nursing and used to provide a focus for the curriculum. Nursing researchers may use models in a number of ways; for example, to identify research questions and variables, interpret findings and provide a theoretical framework for the design of the study. It has been suggested that nursing theory is unpopular in Australia and New Zealand because it is not seen to be used by or useful to clinicians, it is written in alienating language and it predominantly relates to American and British practice.26

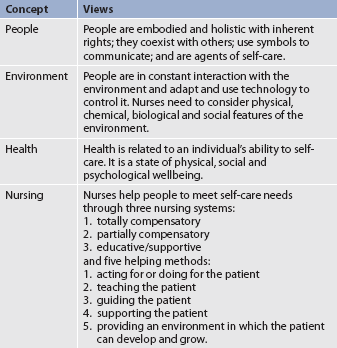

Early theories depend on established theories, such as stress adaptation, systems theory, symbolic interaction or developmental theory. As an example, consider how a team of nurses might apply the self-care model (see Table 1-4).24 The following might be seen in a clinical area of a hospital where a team of nurses is using the self-care model: tea and coffee making facilities for visitors; family and friends visiting specifically at mealtimes and eating with patients; patients explaining what is written in their care plans and making their own contributions; patients holding onto their notes; health professionals asking patients if they may see their notes; patients being part of discussions about their care and treatment; therapeutic goals being set by the patients and discharge planning being led by the patients and families; nurses working with patients to enable them to do as much as they can for themselves; and patient assessments having a self-care framework with questions aimed at determining where it is that individuals are unable to meet their own self-care needs.

APPLIED KNOWLEDGE

Much of the knowledge required to nurse patients in the broad frame of medical–surgical nursing is shared knowledge—medical students, doctors and physiotherapists might all need to know the same things. Furthermore, this shared knowledge may be applied from a number of different disciplinary bases. For example, in the case of a patient with renal failure, the patient, the patient’s family, the dietician and the nurse involved all need to understand the physiology and pathophysiology of the kidney. They also need to draw on social theories that reveal social dimensions of chronic illness, theories of learning to enhance health education opportunities and descriptive theories of experiences of living with renal failure.

From a practical point of view, nursing knowledge is necessary for nurses and patients to make decisions. Patients are included here because it is often the nurse’s role to help patients and their family or friends to find the information they need to make an informed decision. Furthermore, nurses have to be able to understand the therapeutic decisions that medical and allied healthcare professionals make in order to support the patient through the therapy and to explain and discuss the therapy with them when necessary. Nursing-specific knowledge is maintained and continuously developed further through nursing research and reflective practice.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE AND CRITICAL THINKING

Another source of nursing knowledge is experience: the things we know through living and nursing over the years. This knowledge is understood through the process of critical reflection on and in action.27,28 Reflection is a natural technique used by all people, and nurses are encouraged to develop and refine this process further in their professional practice.29 As a part of reflective practice, reflection is a deliberate and systematic review of what has happened in order to learn from the experience and reframe future experiences. A range of strategies can be used for reflection, the most common being the use of journals and self-awareness through supervision.29 To become a reflective practitioner, however, links between reflection, learning and subsequent actions need to be made. The reflective practitioner uses reflection on and in action to determine new behaviours and responses to situations, and to trial these in practice.

Critical reflection is linked to critique and critical thinking. Critical thinking can be defined as reasonable reflection that is focused on deciding what to believe or do.30,31 The emphasis on both reason and decision making connects the intellectual and practical skills required to nurse. Critical thinkers question what is taken for granted and develop a healthy scepticism.32 In relation to nursing, this means that nurses are able to determine what is acceptable practice among the variety of claims made, ranging from research suggesting changes to practice to administrators arguing for changes to be made to the workplace.

Critical thinking also requires that nurses step outside themselves and their particular beliefs and values and attempt to understand other viewpoints rather than dismissing them.30 Critical thinkers listen to alternative viewpoints and attempt to understand perspectives other than their own; they are open to being persuaded by stronger arguments, just as they will use understanding of other perspectives to debate their position with more strength.

The judicious use of questioning both oneself and one’s medical–surgical colleagues promotes learning and enables prudent decision making. The problem-solving framework used in nursing is systematic assessment, diagnosis, intervention and evaluation. The steps in this process are closely aligned to the rational process of critical thinking.32

KNOWLEDGE FOR COLLABORATIVE AND CONTEMPORARY HEALTHCARE PRACTICES

The art and science of nursing is a commitment to the holistic care of people and to treating people equally, with respect for their potential to grow, develop and be self-determining, while also embracing the scientific advances that have alleviated so much disease and suffering in the world and that are bound inextricably in contemporary multidisciplinary healthcare practices.22 Knowledge generation through a range of research methodologies enables nurses to achieve this.

Nursing research

Research is a systematic process of knowledge generation. The steps involved in this process are outlined in Table 1-5. Research techniques, such as literature reviews, sampling, data collection, data analysis and reporting of results, enable researchers to develop and make available reliable information.

TABLE 1-5 The research process

| Phase | Quantitative steps | Qualitative steps |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual | Problem identification, literature review, theoretical framework, hypothesis formulation | Clarify the field of study and personal interests |

| Design and planning | Select design, population, sample, measurement instruments, pilot study, ethical approval | Select a methodology and methods of data collection; identify participants and means of recruitment and data collection; obtain ethical approval |

| Empirical | Undertake data collection and entry | Undertake data collection and transcription of tape-recordings or notes |

| Analytical | Analyse and interpret statistical data | Analyse and interpret textual data, usually with reference to the literature |

| Dissemination | Communicate findings; utilise the findings | Communicate findings; utilise the findings |

Breakthroughs in the management of illness have been extraordinary in the 20th century and the dawning years of the 21st century. Some ideas that have been tested and demonstrated to be useful are: moist wound healing; pressure-relieving devices for the prevention of pressure ulcers; patient information to improve self-care and healthy lifestyles; communication with people who are dying; and nutritional support of older people in hospital. Researchers may set out to test whether a particular intervention is better than another, as in the case of moist wound healing compared with dry dressings, or to explore a complex situation or phenomenon, such as communication with people who are dying. In the former case, researchers set up an experiment and collect numerical data and run statistical tests. In the latter case, researchers collect words or pictures in the form of text (either from direct observation or by talking with people involved) and these textual data are analysed and then reported as an interpretation of events. Neither approach is considered to be more important in nursing than the other.

As in clinical practice, where it is becoming more difficult to draw precise demarcation lines between the healthcare disciplines, it is also becoming more difficult and, indeed, less important to distinguish between medical and nursing research. Nursing research is research in which questions about nursing are asked and investigated. The answers inform nurses and help them to do their work. This may be undertaken by nurses in exclusively nursing research teams or by nurses in multidisciplinary teams. Much nursing research has concentrated on nurses: what and how they learn, deliver, manage and promote nursing. More efforts and money, however, are currently being devoted to clinical research, which investigates the therapies offered and the effectiveness, appropriateness and feasibility of nursing and healthcare interventions.

Nursing students are not usually expected to be researchers but they are expected to appreciate, support and apply nursing research. There is a wealth of research evidence to support medical, allied health and nursing practice in medical–surgical nursing. Wherever possible, research evidence should be used to support learning and should be applied to practice.

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

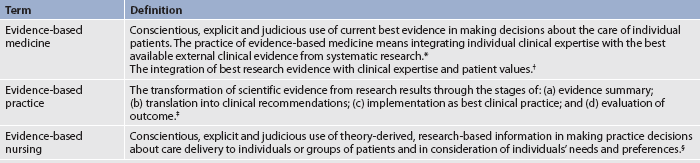

Health-related clinical research is intended to generate knowledge that will enhance the care and treatment of patients. Furthermore, there is little to be gained by investing in research if it does not have an impact on practice. Despite this, the translation and transfer of research findings into practice received practically no attention from any of the health professions until the advent of the evidence-based practice movement. Evidence-based practice provides literature reviews of the best available evidence on a range of research topics and interventions. Table 1-6 and Box 1-3 explain the development of evidence-based medicine, evidence-based practice and evidence-based nursing. The evidence-based movement has a distinct process of synthesis of evidence, development of guidelines, implementation of change and audit (see Fig 1-5).

TABLE 1-6 Evidence-based practice definitions

* Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA et al. Evidence based practice: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996; 312:71–72.

† Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd edn. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

‡ Stevens KR. ACE star model: cycle of knowledge transformation. Academic Center for Evidence-Based Practice. Available at www.acestar.uthscsa.edu.

§ Ingersoll GL. Evidence-based nursing: what it is and what is isn’t. Nursing Outlook 2000; 48:151.

BOX 1-3 Evidence-based practice

Where is evidence found?

• Systematic reviews (e.g. Cochrane Collaboration; available at www.cochrane.org)*

• Special collections of evidence-based practice resources (e.g. The Joanna Briggs Institute; available at www.joannabriggs.edu.au)

*Descriptions can be found at this website, but access to systematic reviews is by subscription only.

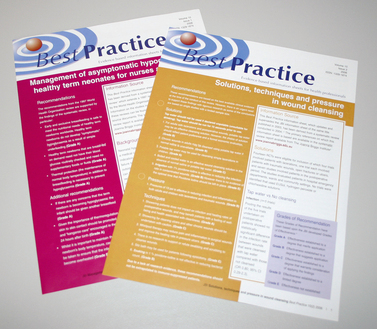

A systematic review is a collection and synthesis of all available research on one particular topic; for example, the efficacy of cardiac rehabilitation programs following myocardial infarction for improving quality of life and reducing recurrence. As such, it is known as secondary research. The systematic review is, nevertheless, considered to be a research project in its own right and members of the review team follow a strict protocol to ensure that all accessible research for a particular question is included and that biases that might skew results are kept to a minimum. The exact steps of the systematic review are detailed on the website of The Joanna Briggs Institute (see Resources on p 21). Summary sheets, known as evidence-based information sheets, best practice information sheets (see Fig 1-6) and evidence-based protocols, give a précis of the research evidence, the sources of the information, implications for practice, implications for research and an estimate of the strength of the evidence. These summaries are prepared by panels of expert clinicians as well as researchers and consumer representatives, and are subject to a peer review process in order to establish their credibility. Thus, in the light of the best available evidence, practice standards are identified and used to benchmark best practice as it occurs. Audit tools are used to monitor report practice processes and outcomes in order to account for the quality of the healthcare service.

Figure 1-6 Best practice information sheets provide findings from systematic reviews in a condensed form.

Source: The Joanna Briggs Institute.

The evidence-based practice movement is provided as an information service to clinicians and should also be of value to learners. There are a number of evidence-based libraries. The Cochrane Collaboration (see Resources on p 21) is the most well-known library and was medically initiated and run; however, there are other collections, such as The Joanna Briggs Institute, which has centres in all states in Australia and in New Zealand, and the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination in the UK. Throughout this book, evidence-based practice boxes are presented that relate to specific clinical problems for which summarised evidence exists. In some cases, the evidence supports current practice and increases confidence that the nursing care will produce the desired outcome. In other cases, the evidence points to a change in practice. In either case, it is important for nurses to be aware of the processes for using evidence to guide nursing practice.33

Nursing care planning

Wherever nursing care is required, there should be a formalised system for deciding what particular patients require by way of nursing care and a means of communicating those decisions to the patients, their family or nominated other, nursing colleagues, and allied healthcare and medical staff. Besides the obvious need for this team to know what everyone is doing, it is necessary for legal reasons to have a record of the process of nursing and the outcomes achieved. A number of tools have been designed to support the construction of a nursing plan of care. Essentially, all nursing plans must be based on the best available evidence gathered from the patient and the rest of the team, experience, commonsense, theory and research. Nursing is adapting to the modern healthcare service by embracing information technologies and standardised multidisciplinary care plans. Nurses need to be able to use standardised care plans and modern technology while still ensuring that the individual patient is not lost amid all this.23

DOCUMENTATION

A number of documentation methods and formats are used, depending on personal preference, agency policy and regulatory standards, such as those maintained by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Patient progress may be documented by nurses with the use of flow sheets, narrative notes, subjective–objective assessment plan (SOAP) charting, clinical pathways and computer-based charting. Every method or combination of methods is designed to document the assessment of patient status, the implementation of interventions and the outcome of interventions. Nurses need to adhere to the principles and legal requirements of nursing documentation relevant to their respective jurisdiction.

Problem lists

Documentation varies significantly from institution to institution, so nurses working for a healthcare agency need to be flexible enough to learn and adjust to differing systems. One approach to documenting patient care is to develop a multidisciplinary problem list for each patient. Nurses, medical practitioners, social workers, dieticians and other healthcare professionals are encouraged to contribute to the list. A comprehensive view of the patient’s problems is achieved by having many different disciplines contribute to the list.

Nurses can easily use the problem list as a basis for identifying nursing diagnoses. For example, if one of the identified problems on the list for a patient with a stroke is hemiparesis, appropriate nursing diagnoses for the nurse to consider may be risk of impaired skin integrity and impaired physical mobility. The problem list is an inherent component of the problem-oriented record, which is a multidisciplinary patient documentation method. A prescribed method of charting, called SOAP charting, is used with this record.

SOAP charting

If a problem-oriented approach is used for documentation, one method of evaluating and recording patient progress is referred to as SOAP charting. This type of progress note is problem-specific and incorporates the components described in Table 1-7. Because the problem list and the record are multidisciplinary, data associated with any identified problem may be recorded by any healthcare provider. In some institutions, however, nurses write SOAP notes in reference to a list of nursing diagnoses. The process of SOAP documentation is as follows:

1. Additional subjective and objective data are gathered related to the area of concern.

2. Based on old and new data, an assessment of the patient’s progress towards the expected patient outcome and the effectiveness of each intervention is made.

3. Based on the reassessment of the situation, the initial plan is maintained, revised or discontinued.

TABLE 1-7 Components of a problem-oriented progress note

| SOAP* | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Subjective | Information supplied by patient or knowledgeable other |

| Objective | Information obtained by nurse directly by observation or measurement, from patient records or through diagnostic studies |

| Assessment | Nursing diagnosis or problem based on subjective data and objective data |

| Plan | Specific interventions related to a diagnosis or problem considering diagnostic, therapeutic and patient education needs |

*Iyer P, Camp N. Nursing documentation: a nursing process approach.

3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby; 1999.

The following is an example of SOAP charting for the nursing diagnosis ‘risk of infection related to traumatised tissue secondary to surgery’ as it would be documented in progress/integrated notes:

Computerised documentation

The use of computers to document patient care, or computerised documentation, is becoming more common in healthcare settings. Computerised documentation systems are usually referred to as an electronic patient record (EPR), electronic client record (ECR), computerised patient record (CPR) or electronic health record (EHR). These records are the patient’s official chart. Data are entered into the healthcare record, making charting easier, faster and generally more available to healthcare providers.33 Software programs quickly allow nurses to enter specific assessment data once and the information is automatically transferred to different reports. Instead of writing lengthy nursing notes, nurses can select choices on a screen that are used to build a comprehensive patient record. Before computerised charting, it was difficult to extract nursing information from the healthcare record because it had to be obtained from paper charts by hand. With computerised records, errors can be reduced and reporting on patient care data is much easier.

One such system used in a number of Australian healthcare agencies is ExcelCare. This software was developed by a team of nurses and nurse educators. ExcelCare allows institutions to define their own units of observations, goals, outcomes and interventions. Based on the items that are selected by the healthcare provider, projected and actual amounts of time can be calculated for care that is given. This provides easily accessible data that assist with decision making regarding human resource allocation and budgeting. ExcelCare enables a multidisciplinary approach so that a comprehensive picture of a patient’s care can be constructed. Easy retrieval of such data helps administration to reduce billing costs and report on length of stay.

Each piece of data that is entered into the record can be tracked and reported on for many purposes. If nursing languages, or taxonomies, are used in information systems for documentation of nursing practice, nurses can track and report on the benefits of nursing care and just what it is that nurses do for patients. This will serve not only to improve practice guidelines but also to facilitate nursing research and easily demonstrate the effectiveness of nursing interventions. This will make nursing care visible while providing a continuing evaluation of nursing’s efficacy.

Nursing informatics

Nursing informatics is a nursing specialty integrating nursing science, computer science and information science in identifying, collecting, processing and managing data and information to support nursing practice, administration, education, research and the expansion of knowledge. This specialisation in nursing allows nurses to work within the information systems (IS) department so that nursing issues can be integrated at the beginning of computer projects rather than being evaluated only when a project is complete. Nursing informatics studies the structure and processing of nursing information to arrive at clinical decisions and to build systems to support and automate that processing. An informatics nurse has a diverse role that ranges from designing, developing, marketing and testing to the implementation, training, use, maintenance, evaluation and enhancement of computer systems. Nursing Informatics Australia (NIA) is a special-interest group of the Health Informatics Society of Australia (HISA) and is a good reference point for nurses.34

THE NURSING PROCESS

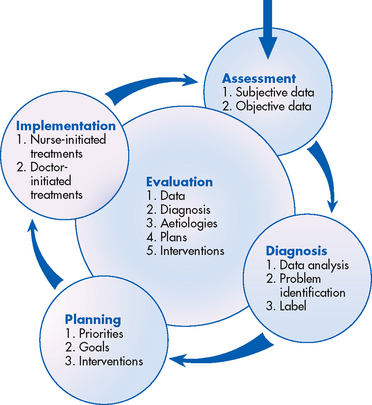

Assessment, diagnosis, planning, intervention and evaluation are rational steps in a systematic approach to problem solving (see Fig 1-7). Since the 1980s this managerial process has been adopted by nursing and named the nursing process. It is used to develop individualised plans that detail the care and outcomes of care for patients. Even though it is not uniformly used in nursing documentation in Australia and New Zealand, it has become a familiar sequence of thought for sorting out ‘what to do’ when nursing a particular patient, and it is used and referred to throughout this book. The process is a series of steps that provides a framework for addressing problems; however, it is nursing theories and nursing knowledge from a range of sources that enable the nurse to fill in the framework and create a nursing care plan for an individual patient.

A number of terms can be used for the five phases of the nursing process (see Box 1-4), which can cause some confusion, so beware when reading other texts and documents. Assessment involves collecting subjective and objective information about the patient. The nursing diagnosis phase involves analysing the assessment data, drawing conclusions from the information and labelling the human response or patient problem. Planning consists of setting goals and expected outcomes with the patient and family, whenever possible, and determining strategies for accomplishing the goals. Implementation involves the use of nursing interventions to activate the plan. In evaluation, the nurse first determines whether the identified outcomes have been met. Then, the overall nursing care given as documented is evaluated.

BOX 1-4 Commonly used terms for components of the nursing process

Assessment

Nursing theories have assessment procedures that provide for a holistic assessment with due regard for the patient’s biophysical, psychological, sociocultural, spiritual and environmental dimensions. For example, using the self-care model the nurse would assess each of the following: universal self-care requisites, developmental self-care requisites and health deviation self-care requisites;24 in other nursing models the nurse would assess the patient on all activities of living35 or on functional health patterns.36 Information gained from the patient is a most important source of data. Assessment forms may also be used as a guide to assessment. These may be developed in particular hospitals or even units within hospitals and serve as a guide to nursing assessment. They are not always overtly associated with a particular nursing model, although they usually have a biopsychosocial perspective. These forms are used in conjunction with an array of assessment tools that are used to estimate and record the patient’s state. For example, three commonly used risk assessment tools for pressure ulcer development are the Norton, Braden and Waterlow scales. Similarly, nurses can use a number of pain assessment tools.

The use of a nursing database (see Ch 3) is recommended to facilitate the collection of data (see Fig 1-8). Nursing interventions are only as sound as the database on which they are formulated, so it is critical that the database be accurate and complete. When possible, information gained from sources such as the patient’s record, other healthcare workers, the patient’s family and the nurse’s observations should be shared with the patient. In cases where patients are unable, for any reason, to represent themselves, another source of reliable information should be sought on their behalf.

Diagnosis

Making a nursing diagnosis is the act of identifying and labelling human responses to actual or potential health problems. Throughout this book, the term nursing diagnosis means: (1) the process of identifying actual and potential health problems; and (2) the label or concise statement that describes ‘a clinical judgment about an individual, family, or community response to actual or potential health problems/life processes. A nursing diagnosis provides the basis for the selection of nursing interventions to achieve outcomes for which the nurse is accountable’.36 The human responses identified frequently result from a disease process. For example, a patient may have the medical diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In this case, the nursing diagnosis would focus on how the disease affects daily functioning. Examples of patient responses to COPD might be anxiety, activity intolerance or an inability to maintain a home.

A number of other terms or situations are not nursing diagnoses but are often mislabelled as such.37 These include the following:

• medical pathological conditions (e.g. coronary artery disease)

• diagnostic tests or studies (e.g. upper gastrointestinal series)

• equipment (e.g. nasogastric tube)

• surgical procedures (e.g. hysterectomy)

• treatments (e.g. pressure ulcer care)

• therapeutic goals (e.g. perform own oral care)

• nursing problems (e.g. difficult to turn)

As noted earlier in this chapter, NANDA has been developing a standardised nursing language for identifying, defining and classifying patients’ actual or potential responses to health problems since 1973. The two main purposes of NANDA are to develop a diagnostic classification system (taxonomy) and to identify and accept nursing diagnoses. In selecting a nursing diagnosis for a patient from the NANDA list, the nurse labels the patient’s responses in a language that specifically identifies and defines the patient’s problem for other nurses and healthcare providers. In addition, the use of the standardised language of nursing diagnoses documents the analysis, synthesis and accuracy required in making a nursing diagnosis. It verifies nursing’s contribution to cost-effective, efficient, quality healthcare.

Currently, NANDA has accepted more than 200 nursing diagnoses for clinical testing (see Appendix B). Each nursing diagnosis has an assigned code number facilitating its use in computerised documentation. The nursing diagnoses used in this textbook are NANDA approved. However, it is acceptable to use non-NANDA approved nursing diagnoses when a new label is identified. The NANDA list is continually evolving as research results are interpreted and as nurses identify new human responses. Therefore, the nurse may encounter diagnoses in clinical practice that are not cited on the list. Revisions of accepted nursing diagnoses and new diagnoses may be submitted to NANDA by individual nurses or nursing groups. For information on submitting diagnostic material, contact NANDA (see Resources on p 21). It is important to note that NANDA’s diagnostic taxonomy is by no means universally accepted.

Planning