Chapter 4 Health promotion and patient education

1. Discuss the concept of health.

2. Outline the social determinants of health.

3. Describe the links between primary healthcare, health promotion and health education.

4. Describe the process of patient education.

5. Describe the principles of adult learning.

6. Identify specific skills that will enhance the role of the nurse as an educator.

7. Discuss the role of the family in patient education.

8. Outline physical, psychological and sociocultural characteristics of the patient that affect the teaching–learning process.

9. Describe the advantages, disadvantages and uses of various education strategies.

10. Describe the importance of documentation in health education.

Education of patients occurs in many places and is commonly undertaken by nurses. The nurse may be working in the community providing education to individuals or groups of patients; the nurse may work in a hospital or community setting with a specific role such as a diabetes educator; or the nurse may be at the bedside educating patients about their care prior to discharge. Nurses need to recognise that every patient interaction they have is a potential for health teaching, regardless of the setting. Health education and health promotion are often opportunistic. They are no longer straightforward concepts: health needs to be considered across the whole spectrum, from an individual perspective, to a community perspective to an entire population. Wherever education occurs, it needs to be relevant and timely, and the nurse needs to know that the patient has learnt.

A core competency of the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia national competency standards is that the nurse will ‘educate individuals/groups to promote independence and control over their health’.1 The Nursing Council of New Zealand also states, as a core competency, that the nurse ‘provides health education appropriate to the needs of clients within a nursing framework’.2 Meeting these competencies is a big challenge when the health of populations is affected by natural disasters; however, these competencies can be quite achievable in everyday nursing interactions. To have an understanding of this education role in health it is essential that the nurse have an understanding of health, primary healthcare, health promotion and, ultimately, patient education. Health education and patient teaching is one of the most challenging aspects of nursing practice today. It is imperative that this aspect is included in all nursing curricula so that nurses are prepared for this important role. This chapter by no means provides all there is to know about health, health education, health promotion and patient teaching, and nurses must continually read more widely about these issues to ensure best practice.

Defining health

There are many definitions of health and nurses should have an understanding of them. In 1946 the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.3 This definition is still quoted in many publications and there have been many versions of similar definitions of health since. It could be suggested that the biomedical model of health is premised on this definition as, in the medical model, health is seen as the absence of disease and the focus is on diagnosis and treatment of the causative organism. In this model the person is considered healthy only when there are no signs or symptoms of disease.4 Holistic health, on the other hand, considers the whole person: the body, mind and spirit need to be in harmony for the person to be considered healthy. While WHO’s early definition of health and the models that arose from it set the ideal for health, what was not recognised at the time is that other determinants—such as living conditions, the environment, housing, poverty and available food—also affect health. These determinants have never been so important than in the current climate of natural disasters worldwide. The Australian Institute of Health & Welfare suggests that the dominant view of health is that it is ‘multicausal: healthiness, disease, disability and, ultimately, death are seen as the result of the interaction of human biology, lifestyle and environmental (including social) factors, modified by health interventions’.5 Whichever definition is embraced, it is clear that there are many factors that impact on the health of nurses and the health of patients.

Indigenous Australians were very forward thinking when, in 1989, they described health from an Indigenous perspective as ‘not just the physical well-being of the individual but the social and cultural well-being of the whole community’. This is a whole-of-life view and it also includes the cyclical concept of life–death–life.6 In New Zealand, Māori have the same perspective on health, which encompasses mind, body and spirit, and this is well described in the Māori health action plan.7 An examination of these and other definitions of health is important to understand the complexities of health. The diversity of patients and their own health beliefs impact on the way care needs to be provided. It is essential that nurses consider their own culturally based values, beliefs, attitudes and practices related to health to ensure that they are able to identify and interpret the meaning of health for patients.4

Determinants of health

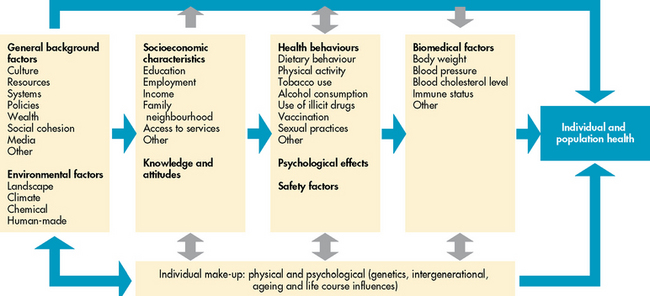

Many factors can potentially determine our health. In 2000, WHO developed 10 social determinants of health: the social gradient, stress, early development, work, unemployment, social support, social exclusion, addiction, food and transport.8 Talbot and Verrinder describe a further set of determinants for health: peace, shelter, education, social security, social relations, income, empowerment of women, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resource use, social justice, respect for human rights and equity.8 All of these factors will raise or lower the health of a population and they can have a positive or negative impact on people. Two other important factors that impact on health are age and gender. These determinants cannot, of course, be altered. By keeping all of these determinants of health in mind, nurses can assess patients appropriately. Figure 4-1 provides a conceptual framework for determinants of health and demonstrates the complex interplay of all factors. While the figure has been developed in the Australian context, it is also relevant to the New Zealand population.

Health for all

PRIMARY HEALTHCARE

Primary healthcare has been defined as ‘a basic level of health care that includes programs directed at the promotion of health, early diagnosis of disease or disability, and prevention of disease’.9 WHO goes further and suggests that it is ‘essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology’.8

In 1978 a significant international conference on primary healthcare, held at Alma-Ata in Russia, defined the way forward for health. The resultant Declaration of Alma-Ata and the challenge for the world at that time was to embrace the principles of primary healthcare. Ten fundamental principles were declared, which can be summarised as: fundamental human rights; equity; community participation and maximum community self-reliance; use of socially acceptable technology; health promotion and disease prevention; involvement of government departments other than health; political action; cooperation between countries; reduction of money spent on armaments in order to increase funds for primary healthcare; and world peace.8 In essence, it was declared that health should be available, affordable and accessible, and that all people should be empowered to make decisions about their care in collaboration with healthcare workers.

This declaration pledged urgent action by governments, health and development workers, and the world community to protect and promote the health of all people.8 The Declaration of Alma-Ata was the beginning of the slogan ‘Health for all by the year 2000’, but subsequent questions have been raised about the achievement of this goal. The Ottawa Charter of 1986, which was built on the Declaration of Alma-Ata, suggested five areas of action: building healthy public policy; creating environments that support healthy living; strengthening community action; developing personal skills; and reorienting healthcare.10 These two declarations have shaped primary healthcare in Australia and New Zealand. These concepts have been built on and countries have been urged to look at their policies to ensure that there is equity in healthcare. The concept of primary healthcare is fundamental to the areas of health promotion, health education and patient teaching. Health promotion and health education are concepts that have been around for the past 50 years.

HEALTH PROMOTION

Health promotion is premised on the philosophy of primary healthcare as described above. Health education and health promotion are concepts that are often used interchangeably (see below). A continuum of health promotion that moves from a population focus to an individual focus has been suggested by Talbot and Verrinder.8 In this continuum there is community action for social and environmental change, which is a socioenvironmental approach. This is followed by a behavioural approach, which considers settings and supportive environments, economic and regulatory activities, health education, skill development, health information and social marketing. The final part of the continuum is the medical approach, which includes screening, individual risk assessment and immunisation.

Health promotion is premised on values, attitudes and beliefs, and nurses need to be aware of their own before giving advice to patients. A developmental approach is appropriate for nurses to understand the physical, psychological, cognitive and behavioural development of patients. Children, adolescents, young adults and older adults have very different needs in relation to patient education and nurses need to consider these.

HEALTH EDUCATION

Health education is linked to health promotion because the purpose of health education is to promote the presence of conditions that assist people in creating health—that is, enhancing conditions for personal and community health.8 It is well recognised that health education and patient teaching are an integral part of nursing care and one of the most challenging roles that nurses have in today’s healthcare environment, where technology, shorter lengths of stay and diverse patient groups dominate the healthcare system. Healthcare industry organisations set standards to ensure consumers and carers are given information that allows them to understand their healthcare requirements.

The challenge for nurses is how and when to provide health education information. Making the time and including patient teaching as a part of practice can make the difference in a patient’s quality of life and health outcomes. Teaching may occur wherever nurses work: from acute care hospitals to communities. Many institutions employ nurse specialists and patient educators to establish and oversee patient education programs; however, all nurses are responsible for patient and family teaching. Every interaction that a nurse has with a patient and family is an opportunity for teaching. Much patient teaching in inpatient facilities is incidental and is incorporated into nursing interventions that prevent complications and promote physiological function. Teaching a patient to cough and deep breathe effectively to prevent atelectasis following surgery or teaching a patient how to use a patient-controlled analgesia machine does not require formal teaching plans. However, when a patient has specific learning needs about health promotion, risk reduction or management of a health problem, it is useful to develop and implement a teaching plan with the patient. The teaching plan includes assessment of the patient’s ability, need and readiness to learn, with identification of problems that can be resolved with teaching. The nurse then determines objectives with the patient, delivers educational interventions and evaluates the effectiveness of the teaching. The teaching and learning process provides a framework for patient and family education and factors that contribute to successful educational experiences, thereby optimising health outcomes. It is also important for the nurse to know how to refer the patient to appropriate technology such as websites and computer applications that may provide health education material. As patients’ length of stay in acute care settings is reduced, making the most of every opportunity to provide health education is imperative.

Teaching–learning process

Teaching is not just imparting information. Learning is not just listening to instruction. Learning occurs when there is an internal mental change characterised by rearrangement of neural paths that may result in a persistent change in behaviour.11 This can be seen in a patient who understands an instruction and is fully informed but chooses not to change behaviour. In this case, teaching gives the patient the capability to make a decision to change behaviour, but the decision to change rests with the patient. Learners are not passive recipients of information but play an active role in the teaching–learning process.8

In patient education, the teaching–learning process involves the patient, the nurse and the patient’s family and/or social support system. The complex nature of each of these variables should be taken into account when planning and implementing the education process. It is important to remember that the teaching–learning process occurs between people who all bring their own values, ideas and experience to the situation, so there must be effective communication and mutual trust and respect.

ADULT LEARNERS

Adult learning principles

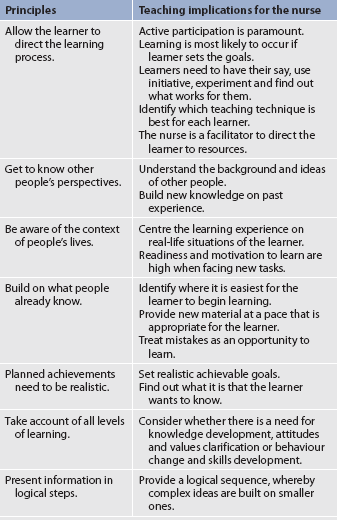

Understanding how and why adults learn is important for nurses to teach patients effectively. Some general guidelines that can be applied to any teaching–learning situation are presented in Table 4-1.

Motivation of adult learners

Motivation for learning and readiness to learn depend on multiple factors, such as need, attitude, beliefs, stimulation, timing and reinforcement. Many of the theories of adult learning have risen from the work of Malcolm Knowles, who identified seven principles of andragogy (adult learning) that are important for the nurse to consider when teaching adults.12

No one theory explains all motives for learning and changing behaviour. Theorists continue to research why people behave as they do. When teaching adults, it is important to identify what is valued by the person to enhance motivation. If the person perceives a need for information to enhance health or avoid illness, or has a belief that a behaviour change has a health value, the motivation to learn is increased. The health belief model has five major variables for the person who believes that specific behaviour will prevent or reduce illness and the value that they place on achieving a particular goal to achieve this.13

Reinforcement is a strong motivational factor for maintaining behaviour. Reinforcement involves rewarding a desired behaviour with a positive stimulus to increase its occurrence. Behaviour may be strengthened by negative reinforcement too, when the behaviour removes a negative consequence, such as pain or illness symptoms.8

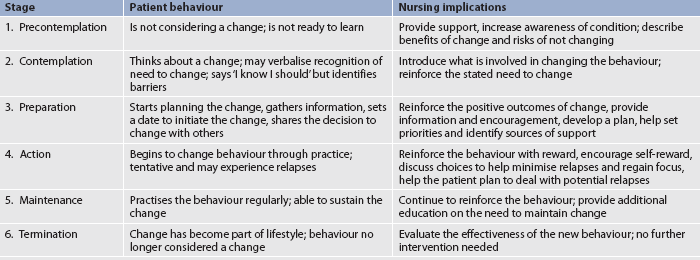

When a change in health behaviour is recommended, patients and their families may progress through a series of steps before they are willing or able to accept a change in health behaviour. Six stages of change have been identified in the transtheoretical model of health behaviour change developed by Prochaska and Velicer.14 These stages of behavioural change and the implications for patient teaching are described in Table 4-2. It is important to note that individuals progress through these stages at their own pace and that progression through the stages is often non-linear and cyclical, with periods of relapse and restarting the process. Assessing the patient’s stage of behavioural change will assist the nurse to formulate an appropriate teaching plan. It is useful to remember the non-linear cyclical nature of this model when setting goals for the patient.

THE NURSE AS TEACHER

Knowledge of subject matter

The scope and setting of nursing practice is large and diverse. Although it is impossible to be an expert in all areas, the nurse can acquire confidence as a teacher by developing a thorough knowledge of the content matter that is to be taught. Accessing the latest evidence about the presenting problem, the health risk, management and appropriate self-care may be necessary if the nurse has limited experience with or knowledge of the subject. For example, when teaching a patient about management of hypertension, the nurse must be able to explain what hypertension is, why it is important to control the disease, and what the patient needs to know about lifestyle and medication management. The nurse also needs to be able to teach the patient to use blood pressure equipment to monitor the blood pressure and to identify situations that should be reported to the healthcare provider. In addition, the nurse needs to provide the patient with additional resources, such as appropriate websites and support organisations (e.g. the National Heart Foundation in Australia or New Zealand). Nurses working in specialised areas, such as cardiac care or women’s health, should focus on knowledge and skills relevant to their area. While it is recognised that patients do have comorbidities, a specific focus can make the nurse a credible and reliable source of knowledge on that subject matter.

It is not unusual for patients to ask questions that the nurse may not be able to answer. In this case, the nurse should acknowledge this and then follow through by seeking additional information to answer the question. Often this response needs to be quick and timely, especially if the patient is in an area where there is a high turnover of patients.

Communication skills

Patient education is an interactive process (see Fig 4-2). It is dependent on communication between the nurse and the patient or family member. During the teaching process the nurse should use basic communication skills, as described in the patient interview in Chapter 3. Some additional communication skills that are particularly important in teaching are discussed in this chapter.

Figure 4-2 Cooperation between the patient and the nurse is necessary for effective patient learning.

Medical jargon is inherently intimidating and frightening to most patients and their families. Patients can feel alienated when complex medical terms are used in their presence if they do not understand what the terms mean. The nurse should begin by defining the medical words or terms that are necessary to understanding the content to be taught. For example, if a patient is told that she has idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, she most likely will need the nurse to interpret this diagnosis in words that mean something to her. The nurse can explain that the term idiopathic is a scientific way of saying ‘for an unknown reason’, dilated means enlarged and cardiomyopathy describes a heart muscle not pumping with full force. Therefore, the patient has an enlarged heart that is not working properly and the reason for this is unknown. With this one-sentence interpretation, the nurse has enhanced the education process. It is imperative that the nurse check the patient’s understanding of what has been conveyed and ask if they have any questions or concerns. Sometimes, writing down a simple explanation can also assist, especially if the patient needs to tell family members what is happening.

The importance of non-verbal communication in the teaching process should be considered. To provide positive non-verbal messages it is important for the nurse to sit facing the patient. If possible, the nurse should raise the bed or sit in a chair so that the nurse’s and patient’s eyes are level. Open body gestures communicate interest and a willingness to share. If time is limited, the nurse should tell the patient upfront how much time can be devoted to the session. This will allow both the patient and the nurse to set priorities on what needs to be taught during the allotted time. Culture needs to be respected in all communication and appropriate interpreters should be used to ensure that the patient has every opportunity to be a collaborative partner in their education.

It is also vital for the nurse to develop the art of active listening. This means paying attention to what is said as well as observing the patient’s non-verbal cues. The nurse must be prepared both physically and mentally to listen. This includes sitting directly in front of the patient, eliminating distractions and trying to dismiss personal worries. The nurse should then concentrate on the patient as a communicator of vital information and allow the patient full hearing by not interrupting. To allow time for listening without appearing in a hurry requires thoughtful organisation and planning on the nurse’s part. Attentive listening enables the nurse to obtain important information needed for the assessment phase of the teaching process and so the nurse’s listening skills during all patient interactions will need to be exceptional. The nurse must ‘tune into’ the cues that the patient may give and respond appropriately. In instances where opportunistic patient education needs to be done and the nurse does not have time to sit and talk to the patient, this may mean returning to talk to the patient at a more appropriate time about issues the patient has raised.

Stressors related to teaching

Lack of time is a major stressor for nurses that detracts from the effectiveness of the teaching effort. Teaching is often not as instantly rewarding to nurses as other interventions and therefore may not be given priority when time is limited and the environment does not value patient teaching. However, it is important to ensure that patient teaching is included in the care plan or clinical pathway established for the patient and is not seen as an ‘add-on’. It is critical that the nurse identifies the patient’s learning needs so that important teaching can be undertaken during any contact with the patient or family.

Another stressor is insecurity about knowledge and competence. This stressor may impair the nurse’s ability to teach effectively: see above for a discussion of the skills required of the nurse as a teacher. A further potential stressor is disagreement between the nurse and the patient regarding the expectations of teaching. The nurse must accept that some patients or families may not be willing to talk about the health problem or its implications. The patient or family may be in denial or hold ideas and values that are in conflict with conventional healthcare. The nurse may face hostility or resentment but must respect the patient’s response to the health problem. These issues need to be explored in the assessment phase.

Yet another stressor for the nurse who is attempting to provide patient education is the current healthcare system. Shortened lengths of hospital stays have resulted in patients being discharged into the community with only the basic elements of educational plans established. In some instances there may be no plan at all. At the same time, healthcare is offering more and complex treatment options, increasing the educational needs of the patient and family. Patients and families also have more difficulty using resources as the complexity of the healthcare system increases. Strategies that can be used to help manage or overcome these stressors are presented in Table 4-3.

TABLE 4-3 Suggested approaches to overcoming nurse–teacher stressors

| Stressor | Approaches |

|---|---|

| Lack of time | Preplan. Set realistic goals. Use time with the patient efficiently, using all possible opportunities for teaching, such as when bathing or changing a dressing. Break teaching and practice into small time periods. Advocate for time for patient teaching. Carefully document what was taught and the time spent teaching in order to emphasise that it is a primary role of nursing and that it takes time. |

| Lack of knowledge | Broaden knowledge base. Read, study, ask questions. Screen teaching materials, participate in other teaching sessions, observe more experienced nurse–teachers, attend classes. |

| Disagreement with patient | Establish agreed-on, written goals. Develop a plan and discuss it with the patient before teaching begins. Introduce a role model to help illustrate therapeutic expectations. Enlist the aid of family and significant others. Revise expectations; learn to be satisfied with small achievements. |

| Powerlessness, frustration | Recognise personal reaction to stress. Develop a support system. Rely on friends and family for positive encouragement. Network with other nurses, health professionals and community leaders to change the situation. Become proactive in legislative processes affecting healthcare delivery. |

FAMILY AND SOCIAL SUPPORT

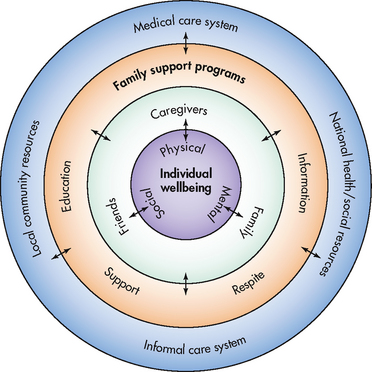

Support provided by the family is important to the patient’s sense of physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing.15 Family members who learn what is needed for home care can promote the patient’s self-care and prevent future hospitalisations.16 It is important for the nurse to identify and include family members and/or significant others in the teaching plans for the patient.

In the family support model (see Fig 4-3) the patient’s ultimate wellbeing is composed of their ability to perform self-care activities through both formal and informal support systems. In this model no part of the system is an independent agent because the wellbeing of the individual depends on support from family, community resources and the medical care system. The support provided by the family greatly affects the patient’s health. Families can provide prolonged periods of support and caregiving, especially when a patient has a severe, life-limiting illness, but this can lead to stress and burnout for the carers. Overwhelmingly, carers want to continue their work, despite the hardships they face in caring for acute and chronically ill family members.17 Where there is no family support, it is essential that the nurse work collaboratively with other healthcare professionals/agencies to develop networks for the patient in the hope of improving the patient’s long-term outcomes.

Patients and families may have different educational needs. For example, the first priority of an older diabetic patient with a large leg ulcer may be to learn how to rise from a chair in the least painful manner. On the other hand, family members may be most concerned about learning the technique for dressing changes. Both the patient’s and the family’s learning needs are important. The patient and family may also have differing or conflicting views of the illness and treatment options. Frequently, the health problem has effects on family roles and functions. Developing a successful teaching plan requires the nurse to view the patient’s needs within the context of the family’s needs. For example, the nurse may teach a patient with right-sided paresis (weakness) self-feeding techniques with special implements, but during a subsequent home visit the nurse finds the patient being fed by the spouse. On questioning, the spouse reveals that it is too difficult to watch the patient struggle with feeding, it takes too long and it is easier to do it for the patient. This is an example of a situation where both the patient and the spouse need additional teaching about the goals of self-care.

Process of patient education

Many different models and approaches are used in the process of patient education and specific institutions or programs may adopt specific models. Whatever approach is used, it will be a parallel of the nursing process. That is, the teaching process and the nursing process both involve development of a plan that includes assessment, diagnosis, setting patient outcomes or objectives (planning), intervention (implementation) and evaluation. Like the nursing process, the teaching process may not always flow in sequential order, but the steps serve as checkpoints to ensure that the relevant variables that affect the teaching–learning activity have been considered.

ASSESSMENT

During the general nursing assessment the nurse gathers data to determine whether the patient has learning needs that teaching can meet. For example, what does the patient know about the health problem and how do they perceive the present problem? If a learning need is identified, a more refined assessment of need is made and that problem is addressed with the teaching process. The general nursing assessment also identifies many variables that affect the teaching–learning process, such as the patient’s physical and mental state of health and sociocultural characteristics. Assessment can also include the family members or carers to determine their abilities to care for the patient at home. The assessment that is performed for the purpose of developing a teaching plan includes physical, psychological and sociocultural characteristics that specifically affect learning and the patient’s characteristics related to the teaching–learning process. Key questions addressing each of these areas are included in Box 4-1.

BOX 4-1 Assessment of characteristics that affect patient teaching

Characteristics and key questions

Physical

• What are the patient’s age and gender?

• Is the patient fatigued? In pain?

• What is the primary diagnosis?

• Are there additional diagnoses?

• What is the patient’s current mental status?

• What is the patient’s hearing ability? Visual ability? Motor ability?

• What drugs does the patient take? Do they affect learning?

Sociocultural

• What is the patient’s present or past occupation?

• How does the patient describe their financial status?

• What is the patient’s educational experience and reading ability?

• What are the patient’s living arrangements?

• Does the patient have family or close friends?

• What are the patient’s beliefs regarding their illness or treatment?

• What is the patient’s cultural/ethnic identity?

• Is proposed teaching consistent with the patient’s cultural values?

Educational

• What does the patient already know?

• What does the patient think is most important to learn first?

• What prior learning experiences establish a frame of reference for current learning needs?

• What has the patient’s healthcare provider told the patient about the health problem?

• Is the patient ready to change behaviour or learn?

• Can the patient identify behaviours/habits that would make the problem better or worse?

• How does the patient learn best? Through reading, listening, doing things?

• In what kind of environment does the patient learn best? Formal classroom? Informal setting, such as home or office? Alone or among peers?

Physical characteristics

The patient’s age is an important factor to consider in the teaching plan. The patient’s experiences, rate of learning and ability to retain information can all be affected by age.18 Barriers to effective learning, such as impairment of vision, hearing, manual dexterity or cognitive ability, may be identified. The effects of ageing are not the only factors to consider. For example, a patient in his twenties who has never thought about his own mortality may be unable to grasp the long-term implications of an unhealthy behaviour, such as smoking. Many young people believe that things happen to other people and not them.

Sensory impairments, such as hearing or vision loss, decrease sensory input and can alter learning. Magnifying glasses and bright lighting may help the patient with impaired vision to read teaching materials. Patients with hearing loss may be helped with hearing aids and teaching techniques that use more visual stimuli. Central nervous system (CNS) function may be affected by disorders of the nervous system, such as stroke and head trauma, but also by other diseases, such as renal disease, liver impairment and cardiovascular failure. Patients with alterations in CNS function may have difficulty learning and may require small amounts of information repeated frequently. Pain, fatigue and certain medications also influence the patient’s ability to learn. No one can learn effectively when in severe pain. When the patient is experiencing pain, the nurse should provide only brief explanations and follow up with more detailed instructions when the pain has been managed. A fatigued and weakened patient cannot learn effectively because of their inability to concentrate. Sleep disruption is common during hospitalisation and patients are frequently exhausted at the time of discharge. Drugs that cause CNS depression, such as opioids and tranquillisers, cause a general decrease in mental alertness. Many chemotherapeutic agents cause nausea, vomiting and headaches, which also affect the patient’s ability to assimilate new information.

The nurse must adjust the teaching plan to accommodate these factors by setting high-priority goals that are need-based and realistic in expectations. Teaching methods should also be adjusted to accommodate limitations in the patient’s ability to learn at any given time. The patient may need follow-up teaching and referral to someone who can answer questions that arise after discharge, but this is often difficult to evaluate as the nurse may never have contact with the patient again.

Psychological characteristics

Psychological factors have a major influence on the patient’s ability to learn. Anxiety and depression are common reactions to illness. Although mild anxiety increases the learner’s perceptual and learning abilities, moderate and severe anxiety limit learning. The nurse must use measures to decrease anxiety before the patient can learn. Both anxiety and depression can negatively affect the patient’s motivation and readiness to learn. For example, a newly diagnosed diabetic patient who is depressed about the diagnosis may not listen or respond to instructions about blood glucose testing and medication management. Discussions with the patient about these concerns or referring the patient to an appropriate support group may enable the patient to learn that management of diabetes is possible.

Patients also respond to the stress of illness with a variety of defence mechanisms, such as denial, rationalisation or even humour. A patient who denies having cancer will not be receptive to information related to treatment options. A patient using rationalisation will imagine any number of reasons for avoiding change or rejecting instruction. For example, a patient with cardiovascular disease who does not want to change dietary habits will relate stories of people who have eaten bacon and eggs every morning for years and lived to be 100. Some patients use humour to filter reality or decrease anxiety, or to escape from the experience of facing threatening situations. A common example of the use of humour is seen when a patient assigns a name and personality characteristics to an intestinal stoma or drainage device. Humour is important and useful in the teaching process, but the nurse must determine when humour is used excessively to avoid reality.

One important psychological determinant of the successful adoption of new behaviours is the patient’s sense of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a person’s belief in their ability to successfully cope with and manage a situation. An individual’s belief in their capability to produce and regulate events in life affects motivation, thought patterns, behaviour and emotions.19 There is a strong relationship between self-efficacy and outcomes of illness management.19,20 Self-efficacy increases when a person gains new skills in managing a threatening situation but decreases when the individual experiences repeated failure, especially early in the course of events. These findings have significant implications for patient and family teaching. The nurse should plan easily attainable objectives early in the teaching sessions, proceeding from simple content to more complex instructions, to establish a positive feeling of success. Using role-play to rehearse new behaviours and peer learning are teaching strategies that can increase self-efficacy in patients and family members.

Sociocultural characteristics

The patient’s sociocultural characteristics influence their perception of health, illness, healthcare, life and death. Social elements include the patient’s lifestyle, status within a family, occupation, income, education, housing arrangement and living location. Cultural elements include dietary and sleep patterns, exercise, sexuality, language, health concepts, values and beliefs. Chapter 2 addresses the issue of culture and health.

Occupation and income

Knowing the patient’s present or past occupation may assist the nurse in determining the vocabulary to use during teaching. For example, a car mechanic may understand the volume overload associated with heart failure as flooding of an engine; and an engineer may understand the principles of physics associated with gravity and pressures when discussing vascular problems. This technique of teaching requires creativity, but can promote a patient’s understanding of pathophysiological processes.

The patient’s occupation may also give the nurse an idea about the patient’s income or financial status. Managing chronic health problems is very expensive and the cost of care should be addressed with the patient or family. The nurse may need to use different teaching resources or improvise materials based on the patient’s ability to afford supplies and equipment. With the introduction of technology such as the internet, iphones and ipads, it is important not to make the assumption that everyone has access to the instant information that this technology affords.

Education and reading ability

The patient’s level of formal education may be helpful in determining appropriate materials and vocabulary to use when teaching the patient. However, the nurse cannot assume that patients read or comprehend at the level of their formal education.

Printed educational materials are extensively used for the purpose of teaching patients and families. Written materials must be appropriate for the patient’s reading level. Australia and New Zealand have very good education systems; however, for a number of complex reasons, some people remain functionally illiterate. People who are functionally illiterate may have difficulty identifying the correct amount of medicine to take based on the information found on the package. Low literacy levels have implications for patient education too. Low-literacy patients hide their deficiency well and it is not always feasible to evaluate a patient’s reading level formally. As a result, it is now recommended that all patient education materials be written at a level that most people will be able to understand (i.e. about Year 8, or approximately 13 years of age). This is an interesting phenomenon in the age of technology, when many people are interacting on the internet.

In addition, in multicultural societies such as Australia and New Zealand, many people do not have English as their first language. Nurses need to consider language skills and reading ability when using or developing educational materials.

Housing arrangements and living location

The patient should be asked about living arrangements that may affect the teaching–learning process. For example, whether the patient lives alone, with friends or with family will influence who else is included in the teaching process. If the patient lives in a rural area at a distance from the teaching site, the nurse may need to make arrangements for continued teaching in that area. The nurse may also refer the patient on to online or telephone support groups.

Cultural considerations

Learning is closely related to the wider culture and the subculture to which a patient belongs. Health practices, beliefs and behaviour vary by religious, ethnic and family group. Many factors affecting patient teaching are included in the cultural assessment in Chapter 2 (see Box 2-3). To prevent stereotyping patients according to cultural group, it is important to ask if there is a cultural group or practice with which the patient identifies. A useful strategy is to ask the patient to describe their beliefs regarding health and illness.

One cultural element that specifically affects the teaching–learning process is a conflict between the patient’s cultural beliefs and values and the behaviours promoted by teaching. For example, a patient who values a healthy body weight can be taught to diet and exercise to attain an appropriate body weight while at the same time improving blood pressure control. However, in another patient’s culture, being overweight may be valued as a sign of financial success and increased sexuality. This patient may have more difficulty accepting the need for diet and exercise unless the importance of blood pressure control is understood.

The nurse must also assess the patient’s use of cultural remedies and healers. For teaching to be effective, cultural health practices must be incorporated into the teaching plan. In addition, it is important to know who has authority in the patient’s culture. The patient may defer to the authority, such as an elder or a spiritual leader or healer, for decisions. In this case, the nurse will also need to identify and work with the decision makers in the patient’s culture.

Educational characteristics

Finally, the nurse should assess those patient characteristics that are directly related to the development of the teaching plan. These factors include the patient’s learning needs, readiness to learn and learning style.

Learning needs

The assessment of learning needs should first determine what the patient already knows, whether the patient has misinformation and any history of past experiences with health problems. Patients with longstanding health problems have different learning needs from those patients with newly diagnosed health problems. The nurse then identifies the information, behaviours or skills known to improve patient outcomes that should be included in the teaching plan. For example, patients who have had myocardial infarctions should be given information regarding the condition, risk factors, medications, diet, psychological concerns, activities, stress management and symptoms so that they can manage their condition and make informed decisions about potential lifestyle changes.21

To individualise learning for a particular patient, the nurse may give the patient a list of the recommended topics and ask the patient to number the topics in order of importance. Another method involves writing each topic in question format on a single card and asking the patient to sort the cards in priority. Examples of questions for a patient with congestive heart failure may include, ‘What are the side effects of my medications?’ and ‘How will I know when I should call my doctor?’ Blank cards could also be provided so that the patient can identify any other needs. By allowing the patient to prioritise their own learning needs, the nurse can begin with the patient’s most important needs and end with the least important. When information regarding life-threatening complications is a factor, the nurse can promote the patient’s priority of learning this content by explaining why the information is a ‘need to know’. Individualisation of learning needs helps ensure that the most important topics are addressed when time limits the comprehensive discussion of all topics.

Readiness to learn

Before implementing the teaching plan the nurse should determine where the patient is in the stages of change process (see Table 4-2). For example, if the patient is in the precontemplation stage, the nurse may simply provide support and increase the patient’s awareness of the problem until the patient is ready to consider a change in behaviour. Nurses in outpatient settings and home healthcare may continue to evaluate the patient’s readiness to learn and implement the teaching plan as the patient moves through the stages of change.

Learning style

Each person has a distinct style of learning, as individual as their personality. The three general learning styles are: (1) visual (reading); (2) auditory (listening); and (3) physical or tactile (doing things, or writing them down). People often use more than one learning style. To assess a patient’s learning style the nurse could ask how the patient learns best and how the patient has learned in the past. During this assessment the nurse should identify patients who do not read or who have limited reading ability. For example, a patient may say that she does not read much but likes to learn from television programs, the radio or illustrations. Auditory methods should always be used when patients identify them as preferred learning styles.

DIAGNOSIS

Information obtained from the assessment related to what the patient knows, believes and is able to do is compared with what the patient wants to know, needs to know and needs to be able to do. Identifying the gap between the known and the unknown helps determine the nursing diagnosis or the deficiency that can be corrected with teaching. A common nursing diagnosis for learning needs is that of deficient knowledge. This refers to the state in which the individual experiences an absence or a deficiency of cognitive knowledge related to a specific topic. Another nursing diagnosis commonly identified when patients have learning needs is that of ineffective health maintenance. This diagnosis refers to an inability to identify, manage and/or seek out help to maintain health.

If deficient knowledge is identified, it is important to specify the exact nature of the deficit so that the objectives, strategies, implementation and evaluation relate to the identified problem. For example, a nursing diagnosis of deficient knowledge related to inability to recognise symptoms of drug toxicity provides the nurse with a clear direction for the teaching–learning process.

PLANNING

Following the assessment and the identification of a nursing diagnosis, the next step in the education process is setting goals, determining objectives for the learner and planning the learning experience. The patient and nurse mutually prioritise the patient’s learning needs and agree on learning objectives (see Fig 4-4). If the patient’s physical or psychological condition interferes with their participation, the patient’s family or significant other can assist the nurse in the planning phase.

Writing specific learning objectives

Writing clear, specific and measurable learning objectives is important. Learning objectives describe the intended result of the learning process, guide the selection of teaching strategies and materials, and help evaluate patient and teacher progress. Learning objectives are parallel to patient outcomes in the nursing care plan and are written using the same criteria. Objectives should be in writing and made readily available to all members of the healthcare team, including the patient and family.

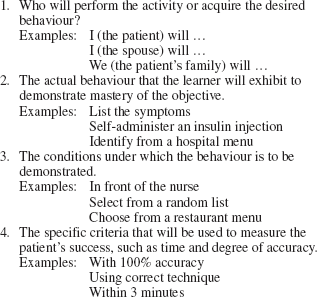

Learning objectives define exactly how patients demonstrate their mastery of the content and contain the following four elements:

Note that well-written learning objectives have precise descriptions using terms with few interpretations. When writing objectives the nurse uses verbs such as ‘identify’, ‘list’, ‘describe’, ‘demonstrate’, ‘name’, ‘recognise’ and ‘compare and contrast’. Vague, ambiguous terms, such as ‘appreciate’, ‘learn’, ‘understand’, ‘enjoy’, ‘feel’ or ‘value’, cannot be measured and should be avoided.

The following is an example of a poorly written learning objective: ‘The patient will appreciate the importance of foot care.’ It is not clear how the patient will demonstrate that they ‘appreciate’ the importance of foot care, when and to whom they will demonstrate this behaviour, or what criteria will be used to determine whether the objective has been met.

The following are examples of well-written learning objectives:

• ‘The patient will be able to demonstrate to the nurse the correct technique for changing her colostomy bag.’

• ‘In front of the nurse, the patient will administer a subcutaneous injection of insulin to himself using correct technique.’

• ‘The patient will select breakfast, lunch and dinner menus keeping within a 2000 mg sodium diet for 3 consecutive days with 90% accuracy.’

• ‘Given a list of symptoms of heart failure, the patient will identify the early symptoms of heart failure with 80% accuracy before discharge from the hospital.’

When learning objectives are clear and specific and when they are written down and available in the patient record, all members of the healthcare team can work together to accomplish the same objectives. Once the objectives are clearly stated, the nurse, patient and patient’s family should choose the strategy or strategies that are most appropriate to meet the objectives of the learning process.

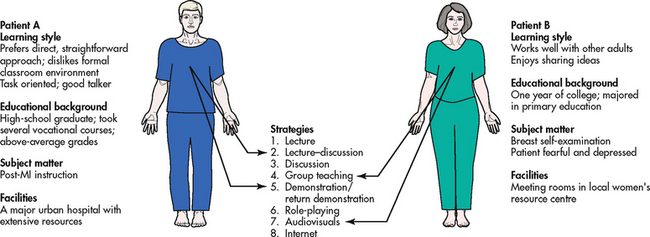

Selecting teaching strategies

Selecting a particular strategy is determined by at least three factors: (1) patient characteristics (e.g. age, educational background, degree of illness, culture); (2) subject matter; and (3) available resources. A discussion of some teaching strategies that can be employed to achieve learning objectives follows. Each has advantages and disadvantages that make it more or less suitable to a particular patient and learning situation (see Fig 4-5).

Lecture

The lecture format is an efficient, versatile and economical teaching strategy that can be used when the amount of time is limited or when a group of patients and family members can benefit from a core of basic information. The nurse presents a series of related ideas or facts to one person or to a group. Usually, the lecture is short, from 15 to 20 minutes, and some visual reinforcement, such as an outline or illustration, emphasises key points. It is important to remember that the average adult learner can remember five to seven points at a time. Disadvantages of the lecture format are that it often has negative ‘school learning’ connotations and individual learning is difficult to evaluate. The nurse is active but the patients are passive unless they are allowed to participate or ask questions. A lecture format is useful for health promotion activities (e.g. a public lecture about osteoporosis as a public health strategy).

Lecture–discussion

The lecture–discussion can overcome some of the disadvantages of the lecture only. With this strategy, the nurse presents specific information by using the lecture technique, followed by a period during which patients and their families ask questions and exchange points of view with the nurse. This strategy assists patients in becoming active participants in the learning process and creates a more informal give-and-take learning environment.

Discussion

The purpose of discussion may be to exchange points of view concerning a topic or to arrive at a decision or conclusion. The nurse can discuss content with an individual or with a group, keeping the specific learning objectives in mind and clarifying information as needed. Participants’ questions can also help the nurse to identify and correct inaccurate information. This strategy is a good choice when patients have previous experience with a subject and have information to share, such as smoking cessation, post-coronary artery bypass surgery or preoperative teaching classes. The discussion allows patients or family members to participate actively and to apply their own experiences and observations to the learning process. The informal sharing and non-threatening environment of discussions are positive factors, but this format usually requires more time depending on the topic and the number of participants.

Group teaching

There are two kinds of group teaching. In the first, the nurse acts as a facilitator, or helper, for group sharing about a common problem. As a facilitator, the nurse participates by keeping information moving among all group members (see Fig 4-6). The nurse may introduce the patient to an existing group or may form a group of patients with similar problems, such as women who are carers.

A second kind of group teaching involves peer teaching as found in support groups. A support group is a self-help organisation that can provide continuing information, shared experiences, acceptance, understanding and useful suggestions about a problem or concern. Patients with problems such as impotence, cancer, alcoholism, Parkinson’s disease, compulsive overeating, diabetes or heart surgery can benefit from peer teaching. The nurse should actively look for opportunities to refer a patient or family to a support group. This action should be taken in addition to, not instead of, the nurse’s planned teaching sessions.

Demonstration/return demonstration

The demonstration/return demonstration is a common nursing strategy. The purpose is to show how to perform a motor skill, such as a dressing change, injection or blood pressure measurement (see Fig 4-7). The focus is on correct procedure and application. To handle this strategy correctly, the nurse tells the patient the purpose of the demonstration and makes sure that the patient can see and hear clearly. Then the nurse presents the demonstration in an informal manner, defines unfamiliar terms and watches for signs of confusion from the patient. The nurse clarifies and repeats as needed and then the patient returns the demonstration with the nurse as observer. The entire process should last no more than 15–20 minutes. Motor skills take practice to achieve and the procedure should be practised by the patient between teaching sessions. Consideration should also be given to the context in which the skills will be taught and used. For example, at home the resources that will be required and available may be different from those used in a hospital or community centre.

Role-play

Role-play is another strategy that the nurse may employ depending on teaching objectives. This format is most often used when patients need to examine their attitudes and behaviours, when they need to understand the viewpoints and attitudes of others, or when they need to practise carrying out thoughts, ideas or decisions. This strategy is challenging for nurses because they are responsible for defining the problems, determining the goals, setting the climate and determining the situation and roles to be played. The nurse gives information and clear instructions to participants and observers and provides time for feedback and evaluation. Role-playing requires maturity, confidence and flexibility on the part of the participants. It is important to remember that some patients may feel uncomfortable and inhibited with this method. Role-playing takes time, which must be factored into the teaching plan. An example of the use of role-playing is a wife who needs to rehearse how to talk with her husband about his need to quit smoking. In this case, ‘play acting’ or practising the discussion with the nurse ahead of time may be a helpful strategy.

Audiovisual and printed materials

Audiovisual and printed materials, including videotapes, DVDs, slides, posters, computer-based programs, charts, audiotapes, books, brochures and pamphlets, are commonly used to complement/supplement other teaching strategies. The use of audiovisual materials can enhance the presentation of information because it promotes learning through both visual and auditory stimulation. To use this strategy, the nurse must know what materials are available within the facility, from support agencies and from professional groups. These materials should be previewed and evaluated for accuracy, completeness, up-to-date research and appropriateness to the learning objectives before being shown to patients and their families. The use of audiovisual materials can be extremely beneficial, particularly when teaching content that is largely visual, such as the steps and processes of procedures (e.g. dressing changes, injections, haemodialysis). Where possible, patients should be given a copy of materials to write notes on during the session and later for reference at their convenience.

A wealth of printed health-related material is available for patient education. Printed materials are most often used in combination with previously presented teaching strategies. For instance, following a lecture on the physiological effects of smoking, the nurse may distribute a pamphlet from the Cancer Council that reviews and reinforces the topic. Or the nurse may select a book or magazine article written by a woman who has had a mastectomy and suggest that the patient read this material to prepare for other teaching sessions. Written materials are always recommended for patients whose preferred learning style is reading.

Written material must be appropriate for the reading level of the patient, as discussed earlier. When writing teaching materials the nurse can use several techniques to reduce the reading level, including the following: (1) give key information first using bold or italics; (2) use short, common words of one or two syllables; (3) define medical words in simple language if they must be used; (4) keep sentences under 10 words if possible, and 15 at the most; (5) use pictures or drawings; and (6) use an active voice, as in the manner of speech.

Major resources for acquiring relevant printed material include the hospital or healthcare facility library, pharmacies, public libraries, Commonwealth and state agencies, universities, voluntary organisations and research centres. Materials that promote specific commercial or proprietary products should be avoided.

Internet

The use of the internet for self-education by patients is increasing at a phenomenal rate. Many patients use their own computers or those available at public libraries to access health information on the internet. The internet also offers established education programs designed for specific learners. There are now many nurse-designed, internet-based information and support systems for patients with any number of health related disorders.

The Pew Internet Project reports that 80% of people who use the internet use it to gather health information. Factors that predict use of the internet for this purpose include access to high-speed internet connections, younger age, college education and confidence in using technology.22,23 Patients who are chronically ill are more likely to base health decisions on the information they find on the internet.22

Using a search engine, nurses and patients can type in the name of a condition and what they need to know about it, and they will find a multitude of information at the click of a button. The challenge is whether the information is reliable and evidence-based and whether the user can discern this. Thus, using the internet as a source of information is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it offers a large number of high-quality health resources and poses seemingly unlimited opportunities to inform, teach and connect healthcare professionals and patients alike. On the other hand, much of the information is incomplete, misleading, inaccurate and not based on fact.

As a result, nurses must have adequate computer competency and literacy to review and evaluate information and programs available on the internet. Being able to understand the principles of web searching for medical information and to instruct patients and families in obtaining valid information is critical.24 All patients who use the internet must be taught how to identify reliable and accurate information. The nurse should encourage patients to use websites established by the government, universities or reputable medical or health-related associations. The information explosion has also seen the development of a massive number of YouTube sites. The nurse must be able to speak to the patient in an informed way about these sites to ensure that the patient understands the need to access health information from reputable and well-informed sources.

IMPLEMENTATION

During the implementation phase the nurse uses the planned strategies to present information and demonstrations. Verbal and non-verbal communication skills, active listening and empathy are incorporated into the process. Based on the assessment of the patient’s physical and psychological condition, the nurse can determine how much active participation the patient can assume.

In implementing the teaching plan the nurse should remember the principles and characteristics of the adult learner. Reinforcement and reward are important but the nurse should be aware that phrases such as ‘very good’ or ‘aren’t you doing well?’ in the tone one would use with a child can be very condescending to adult learners. Techniques to enhance the teaching process with adults are presented in Box 4-2.

BOX 4-2 Techniques to enhance patient learning

• Keep the physical environment relaxed and non-threatening.

• Maintain a respectful, warm and enthusiastic attitude.

• Let the patient’s expressed needs direct what information is provided.

• Focus on ‘must-know’ information, saving ‘nice-to-know’ information if time allows.

• Involve the patient and family in the process; emphasise active participation.

• Be aware of and take into consideration the patient’s previous experiences.

• Emphasise the relevance of the information to the patient’s lifestyle and suggest how it may provide an immediate solution to a problem.

• Schedule and pace learning experiences according to the patient’s needs and abilities.

• Individualise the teaching plan, even if standardised plans are used.

• Emphasise helping the patient to learn and not just transmitting subject matter.

• Review written materials with the patient.

• Remember that simple is best.

• Affirm progress with rewards valued by the patient to reinforce desired behaviours.

EVALUATION

Evaluation is the final step in the learning process and is a measure of the degree to which the patient has mastered the learning objectives. The nurse monitors the patient’s performance level so that changes can be made as needed. The nurse may find that the patient has achieved the goals. However, if certain goals are not reached, the nurse may need to reassess the patient and alter the teaching plan. If the patient has developed new needs, the nurse then plans new goals, content and strategies.

For example, an older man with diabetes mellitus entered the hospital with a blood glucose level of 30.5 mmol/L. When the student nurse began to prepare his insulin injection, the registered nurse asked, ‘Are you going to have him give his own insulin and observe his technique?’ ‘Oh, no’, replied the student nurse, ‘He’s been a diabetic for 20 years!’ The student nurse assumed that the patient would know how to perform this task correctly. The two nurses returned to the patient’s room and asked him to prepare the insulin injection. The patient filled the syringe with 20 units of insulin and 20 units of air, instead of 40 units of insulin. After correcting the dosage and questioning the patient more fully, the nurses concluded that the patient could not accurately see the markings on the syringe and that he may have been administering insufficient insulin to himself for a long period of time. His vision was not as good as it had been 20 years ago and now needed special equipment to administer the insulin safely and accurately.

Evaluation techniques may be short term or long term. Short-term evaluation techniques are used to quickly evaluate the patient’s mastery of a concept, skill or behaviour change and can be accomplished in the following ways:

1. Observe the patient directly. ‘Show me how you will change your dressing.’ ‘Let me see how you administer your injection.’ By observation, the nurse determines whether a task has been mastered, if further instruction is needed or if the patient is ready for new or additional content. If a task is mastered, it is vital that the nurse affirms the patient’s newly acquired skill. Affirmation presented in an appropriate manner for an adult is a strong motivating factor for continued learning.

2. Observe verbal and non-verbal cues. If the patient asks the nurse to repeat instructions, asks questions, shakes their head, loses eye contact, slumps or droops in the chair or bed, becomes restless and fidgety, or otherwise expresses doubt about understanding, the patient may be indicating that further instruction is needed or an alternative approach should be taken. These clues may also indicate that the patient is tiring and has lost their concentration and may need a rest before proceeding. The nurse must be alert to the patient’s non-verbal as well as verbal cues, bearing in mind cultural nuances.

3. Ask direct questions. ‘What are the major food groups?’ ‘How often must you change your dressing?’ ‘What should you do if you develop chest pain after returning home?’ Open-ended and clarifying questions will provide more information about the patient’s understanding than questions that require a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

4. Talk with a member of the patient’s family or support system. ‘Is he eating regularly?’ ‘How is he handling the walker?’ ‘When is she taking her medications?’ Because the nurse cannot be with the patient 24 hours a day, it is important to talk to other people who have contact with the patient.

5. Seek the patient’s self-evaluation of progress. What evidence does the patient have that the objectives are being met? Is the patient confident or unsure? Is the patient ready to go forward with new material? It is important to remember that self-direction is important in adult learning. By seeking out the patient’s opinion, the nurse is allowing the patient input into the evaluation process.

These short-term evaluation techniques can be used frequently and interchangeably to keep informed of the patient’s progress and assess changing needs.

Long-term evaluation requires follow-up by the nurse, outpatient clinic or outside agency. The nurse’s role is to explain to the patient the positive outcomes associated with regular re-evaluation by someone familiar with the patient’s needs. The nurse should set up a schedule of visits for the patient before the patient leaves the hospital or clinic or refer the patient to relevant agencies. The nurse keeps written documentation of follow-up telephone calls or mailed, written reminders to urge the patient to maintain the follow-up schedule. The patient’s family or support person should be familiar with the follow-up plan so that everyone is involved in the patient’s long-term progress.

The nurse takes the initiative in contacting people or agencies involved in the patient’s long-term follow-up. The nurse should telephone, write to, email or fax these healthcare professionals and supply them with the education plan, including learning objectives, teaching plan and short-term evaluation measures. These data are charted in the patient’s medical records for further use.

There are very few educational outcome studies reported in the literature. A well-designed outcome study will provide evidence of the effectiveness of an educational intervention. Outcome studies can assist nurses to evaluate the effects of patient education efforts and identify gaps in their processes and systems for teaching patients. Information about which educational interventions, programs and methods work best can also be obtained from outcome studies and inform decision making.

Documentation is an essential component of the entire learning transaction. The nurse records everything from the assessment through to short- and long-term plans for evaluation. The nurse should also document the education and advice given to the patient. As mentioned, the documentation should be forwarded to the agency or healthcare professional providing long-term follow-up. Because many different members of the healthcare team will use these records in different places and for different reasons, the teaching objectives, content, strategies and evaluation results should be written clearly and completely.

Standardised teaching plans are often included in care plans and clinical pathways and have become an accepted method of developing a teaching plan. Standardised teaching plans contain widely accepted knowledge and skills that a patient and family need to know concerning a specific health problem or procedure. However, the nurse should always individualise these plans to meet the patient’s specific needs.

Example of the teaching process

CASE STUDY

Patient profile

Jane is visiting a pre-admission clinic for preliminary testing and preparatory diagnostic examination for a hysterectomy. The nurse is aware that a patient undergoing a hysterectomy is often deeply concerned about her self-concept as a woman. The nurse also knows that such patients need to express their feelings in an atmosphere of support and understanding. Therefore, the nurse has sought to listen attentively and ask questions carefully in order to assess Jane’s feelings about and knowledge of her surgical procedure. The nurse has asked open-ended questions, such as ‘How do you feel about having the surgery?’ and ‘What concerns do you have about undergoing a hysterectomy?’ By establishing a climate of trust and a counselling relationship, the nurse has completed the following assessment.

Psychological dimension

Patient appears mildly anxious about surgery and worried about her husband’s acceptance of her sexuality. She is also worried about missing work and leaving her classes to a substitute teacher. She states that she does not ‘let physical problems get me down’, and that she dislikes ‘pills and hospitals’. She also states that she is used to ‘teaching’ and not being ‘taught’ and she tries to dominate any conversation or input from the nurse.

Sociocultural dimension

Married with one child (son) age 23. Mother had a mastectomy at age 51; father healthy. Two younger sisters; both experienced difficult pregnancies but are otherwise healthy. Patient describes family communication as very good. She describes her lifestyle as work oriented and says that her friends are primarily teaching colleagues. Her Christian background places a high priority on family and work. One of her close friends has previously undergone this procedure.

Learning style

Responds well to formal lectures but likes to be involved in discussion groups. Enjoys reading.

Determine objectives

During the visit to the pre-admission clinic, Jane states that she would like to learn more about the details of the upcoming planned surgical procedure. Together, Jane and the nurse identify the following objectives.

Following the teaching session, I (Jane) will be able to:

1. describe to the nurse the surgical procedure (hysterectomy)

2. express to the nurse and my husband my feelings about maintaining an active and fulfilling sex life

3. complete arrangements with my family and school principal for convalescence and return to normal activities

4. list the general recovery experiences that are expected and under what circumstances to seek medical advice

5. discuss ‘old wives’ tales’ regarding hysterectomy and verbalise concerns regarding undergoing the hysterectomy

6. identify ways to avoid constipation, weight gain and potential depression during the recovery period

7. identify ways to return to baseline sexual activities comfortably.

1. The nurse is teaching a middle-aged woman in a clinic about various methods to relieve the patient’s symptoms of menopause. The goal of this teaching would be to:

2. When planning teaching with consideration of adult learning principles, the nurse would:

3. A necessary skill of the nurse in the role of teacher is the ability to:

4. When the nurse is feeling stressed about the limited time available for patient teaching, a strategy that might be used is:

5. The nurse includes family members in patient teaching primarily because:

6. When the nurse, the patient and the patient’s family decide together what strategies would be best to meet the learning objectives, the step of the teaching process that is occurring is:

7. A patient characteristic that enhances the teaching–learning process is:

8. An example of a correctly written learning objective is:

9. A patient tells the nurse that she enjoys talking with others and sharing experiences but easily falls asleep when reading. In planning teaching strategies with the patient, the nurse recognises that the patient would probably learn best with:

10. Short-term evaluation of teaching effectiveness includes:

1 Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council. National competency standards for the registered nurse. Available at www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-and-Guidelines.aspx. accessed 23 March 2011.

2 Nursing Council of New Zealand. Competencies for the registered nurse. Available at www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/competenciesrn.pdf. accessed 23 March 2011.

3 Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19–22 June 1946, signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 states (Official records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948. Available at: www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html. accessed 23 March 2011.

4 Jarvis C. Physical examination and health assessment, 5th edn. St Louis: Elsevier, 2008.

5 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Australia’s health, 2010. Australia’s health series no 12. Cat. no. AUS 122. Canberra: AIHW, 2010.

6 Department of Health and Ageing. National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-oatsih-pubs-healthstrategy.htm. accessed 23 March 2011.

7 New Zealand Ministry of Health. Whakatataka: Maori health action plan. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/5583, 2006–2011. accessed 23 March 2011.

8 Talbot L, Verrinder G. Promoting health: the primary health care approach, 4th edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2010.

9 Harris P, Nagy S, Vardaxis N, eds. Mosby’s dictionary of medicine, nursing and health professions. Sydney: Elsevier, 2006.

10 World Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion. Available at www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf, 1986. accessed 23 March 2011.

11 Redman BK. The practice of patient education, 10th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2007.

12 Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development, 6th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2005.

13 Jirojwong S, Liamputtong P. Population health and health promotion. Oxford: Melbourne, 2009.

14 Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48.

15 Waller MA. Gay men with AIDS: perceptions of social support and adaptational outcome. J Homosex. 2001;41(2):99–117.

16 Gerstle JF, Varenne H, Contento I. Post-diagnosis family adaptation influences glycemic control in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(8):918–922.

17 White K, D’Andrew N, Auret K, et al. Learn now: live well. An educational programme for caregivers. Inter J Palliative Nurs. 2008;14(10):497.

18 Kelley K, Abraham C. Health promotion for people aged over 65 years in hospitals: nurses’ perceptions about their role. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(3):569.

19 Farrell K, Wicks MN, Martin JC. Chronic disease self-management improved with enhanced self-efficacy. Clin Nurse Res. 2004;13(4):289–308.

20 Resnick B. A longitudinal analysis of efficacy expectations and exercise in older adults. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2004;18(4):331–344.

21 Jallinoja P, Absetz P, Kuronen R, et al. The dilemma of patient responsibility for lifestyle change: perceptions among primary care physicians and nurses. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25(4):244.

22 Fox S, Jones S. Pew Internet and American life project: the social life of health information. Available at www.pewinternet.org/∼/media//Files/Reports/2009/PIP_Health_2009.pdf, 2009. accessed 26 March 2011.

23 Watson A, Bell A, Kvedar J, et al. Reevaluating the digital divide: current lack of Internet use is not a barrier to adoption of novel health information technology. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):433.

24 Anderson PF, Allee NJ. Medical library association encyclopedic guide to searching and finding health information on the web. Available at www-personal.umich.edu/∼pfa/mlaguide/info/siteinfo.html, 2004. accessed 26 March 2011.

Asthma and Respiratory Foundation (New Zealand). www.asthmanz.co.nz

Australian Health Promotion Association. www.healthpromotion.org.au

Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. www.aihw.gov.au

Cancer Council Australia. www.cancer.org.au

Cancer Society of New Zealand. www.cancernz.org.nz

Diabetes Australia. www.diabetesaustralia.com.au

Diabetes New Zealand. www.diabetes.org.nz

Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand. www.hpforum.org.nz

National Asthma Council Australia. www.nationalasthma.org.au

National Heart Foundation (Australia). www.heartfoundation.com.au

National Heart Foundation (New Zealand). www.nhf.org.nz

New Zealand Ministry of Health. www.health.govt.nz

Online Pharmacy. www.onlinepharmacy.com.au

World Health Organization. www.who.int/en